Published online Feb 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i2.34

Peer-review started: September 10, 2019

First decision: September 26, 2019

Revised: November 21, 2019

Accepted: December 19, 2019

Article in press: December 19, 2019

Published online: February 27, 2020

Processing time: 169 Days and 15.2 Hours

A significant number of patients with liver cirrhosis concomitantly develop some type of solid or hematological cancer, including lymphoma. Treatment of patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis is challenging for physicians due to the clinical characteristics related to cirrhosis, including biochemical and functional abnormalities, as well as portal hypertension and lack of scientific evidence, limiting the use of chemotherapy. Currently, experts recommend only offering oncological treatment to patients with compensated cirrhosis.

To evaluate the clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma treated with chemotherapy.

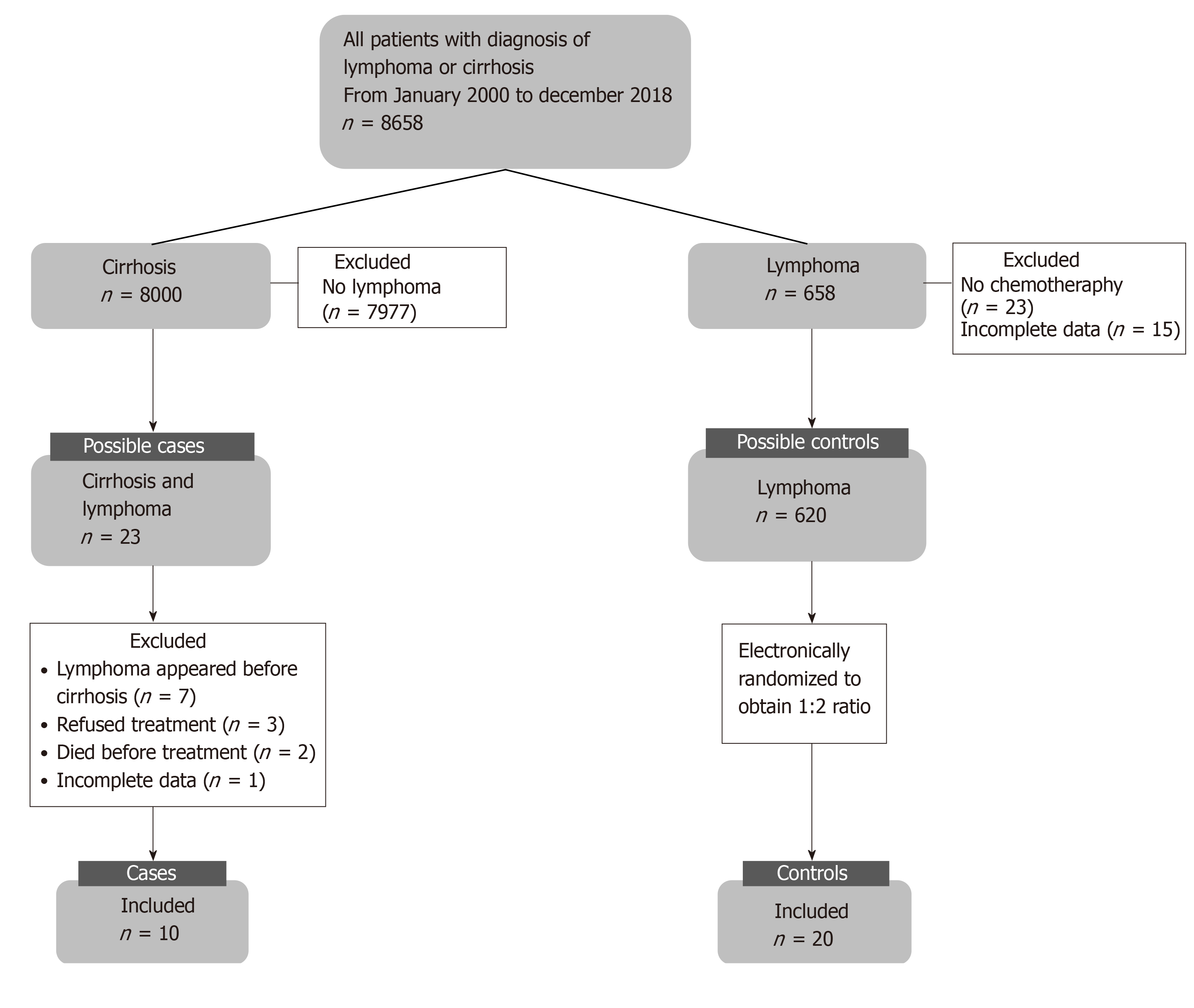

This was a case-control study conducted at a tertiary care center in Mexico. Data was recorded from medical files and from 8658 possible candidates with cirrhosis and/or lymphoma (2000 to 2018). Only 23 cases had both diseases concomitantly; 10 patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma (cases) met the selection criteria and were included, and 20 patients with lymphoma (controls) were included and matched according to age, sex, and date of diagnosis, type and clinical stage of lymphoma. All patients received treatment with chemotherapy. For statistical analysis, descriptive statistics, Shapiro-Wilk test, Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used. Survival was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves and Log-rank test.

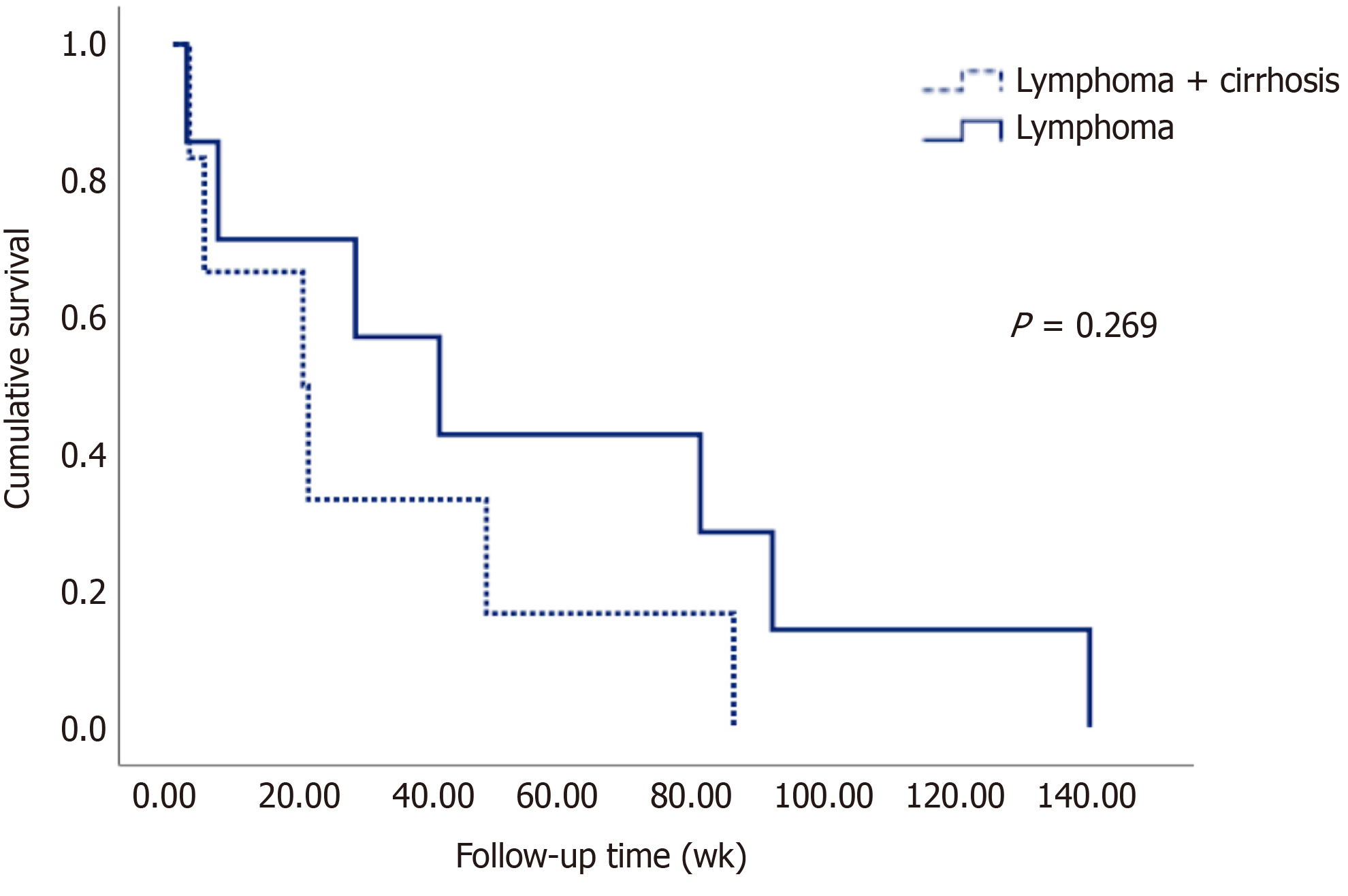

There were differences in biochemical variables inherent to liver disease and portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. The most frequent etiology of cirrhosis was hepatitis C virus (50%); 80% were decompensated, the median Child-Turcotte-Pugh score was 7.5 (6.75-9.25), and mean Model for End-stage Liver Disease was 11.5 ± 4.50. Regarding lymphomas, non-Hodgkin's were the most common (90%), and diffuse large B cell subtype was the most frequent, with a higher International Prognostic Index in the cases (3 vs 2, P = 0.049). The chemotherapy regimens had to be adjusted more frequently in the case group (50% vs 5%, P = 0.009). The complications derived from chemotherapy were similar between both groups (80% vs 90%, P = 0.407); however, non-hematological toxicities were more common in the case group (30% vs 0%, P = 0.030). There was no difference in the response to treatment between groups. Survival was higher in the control group (56 wk vs 30 wk, P = 0.269), although it was not statistically significant.

It may be possible to administer chemotherapy in selected cirrhotic patients, regardless of their severity, obtaining satisfactory clinical outcomes. Prospective clinical trials are needed to generate stronger recommendations.

Core tip: Treatment in patients with liver cirrhosis and lymphoma represents a challenge for physicians given the lack of scientific evidence. Experts recommend offering oncological treatment only to patients with compensated cirrhosis. In this study, we included mainly decompensated patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma, and when compared to patients with lymphoma, we observed that clinical characteristics, response rate and complications derived from chemotherapy were similar in both groups. Chemotherapy was adjusted more in patients with liver dysfunction; however, this did not alter the response to treatment or prognosis. We propose that lymphoma treatment can be provided in patients with cirrhosis at any clinical state.

- Citation: González-Regueiro JA, Ruiz-Margáin A, Cruz-Contreras M, Montaña-Duclaud AM, Cavazos-Gómez A, Demichelis-Gómez R, Macías-Rodríguez RU. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes in patients with liver cirrhosis and lymphoma. World Journal of Hepatology 2020; 12(2): 34-45

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i2/34.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i2.34

Liver cirrhosis and cancer are two major public health issues due to the high incidence and prevalence of each of these diseases. The fact that these diseases are relatively frequent in the general population increases the likelihood of having them simultaneously[1,2]. It is well known that liver cirrhosis is the main risk factor for developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC); however, it also increases the risk of having other extrahepatic malignancies[3,4]. Considering that both entities have common risk factors, such as alcohol consumption, smoking, obesity and metabolic syndrome, they may appear concomitantly[5-10].

Since HCC is the most common type of cancer in cirrhotic patients, most of the literature is centered on its management. Therefore, the management of other types of cancer, especially those less frequent in this population, may present a bigger challenge given that treatment-related hepatotoxicity can significantly affect the prescription and response, as well as the incidence of adverse events.

Lymphomas are malignant neoplasms of B, T and natural killer cells that represent approximately 4.7% of all malignant tumors[11]. There are two main types, Hodgkin lymphomas and non-Hodgkin lymphomas, which represent 10% and 90% of all of these, respectively. Lymphomas can be divided into indolent or aggressive according to their immunophenotype. With treatment, the five-year survival rates for non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphomas are 72% and 86.6%, respectively[11]. Currently, with advances in chemotherapy, it is estimated that between 50% and 80% of all cases are likely to be cured when optimal therapy is provided[12,13]. However, treatment of lymphoma in patients with cirrhosis is a difficult task, and even the involvement of a multidisciplinary team may still not be enough, considering the lack of published literature about clinical outcomes, the narrow therapeutic index of the drugs and the complicated safety problems that are typical in these patients.

A review article by the European Society of Medical Oncology published in 2016 establishes expert recommendations on the treatment of this type of patient, indicating that it is always important to consider the severity of cirrhosis to establish the best therapeutic strategy[14]. However, there are no available studies evaluating survival and the different chemotherapy regimens used in patients who present concomitantly with lymphoma and cirrhosis.

The appropriate strategy for chemotherapy treatment in patients with lymphoma and liver cirrhosis has not yet been defined. Since most clinical trials for lymphoma exclude patients with cirrhosis and vice versa, the available knowledge about clinical outcomes and the use of chemotherapeutic agents in this context is based only on recommendations from pharmaceuticals and experts, case reports, case series and clinical trials investigating the usefulness of different drugs in the context of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Due to the lack of guidelines for the management of these patients, there are only small case series and case reports where the authors describe the therapy used in patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis, treated effectively and safely[15-17]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to evaluate clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes (survival, the type of chemotherapeutic regimen used, and the response rate and complications derived from it) in patients with liver cirrhosis and lymphoma compared with patients with lymphoma.

This was a case-control study conducted at a tertiary care center in Mexico City (Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán, INCMNSZ). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association and was approved by our Institutional Ethics Committee with Ref. No. 2914. All patients over 18 years of age with a diagnosis of liver cirrhosis and/or lymphoma from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2018, were considered for inclusion. No written informed consent was obtained for the retrospective nature of this study.

The cases included patients with an established diagnosis of liver cirrhosis and lymphoma. The diagnosis of cirrhosis was established by clinical tests (non-invasive markers, biochemical markers and evidence of portal hypertension in ultrasonography or the presence of esophageal varices in endoscopy) or liver biopsy. The severity of the liver disease was assessed according to Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP), Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD), and the MELD-Na (MELD sodium) scores. The criterion for decompensated cirrhosis was defined by a CTP class B or C or by the presence of an overt clinical decompensation (jaundice, variceal hemorrhage, ascites, hepatic encephalopathy). The diagnosis of lymphoma was established by histopathology. Patients who had a diagnosis of lymphoma prior to the diagnosis of liver cirrhosis, those who refused treatment with chemotherapy, those who died prior to administration of the chemotherapy regimen, and those with incomplete data in the medical records were excluded.

The control group included patients with lymphoma diagnosed by histopathology, with no evidence of liver disease. This group was electronically randomized for selection. Patients who were not treated with chemotherapy and those with incomplete data in the medical records were excluded. The ratio of controls and cases was 2:1. Controls were adjusted with cases according to age (older or younger than 60 years), sex, date of diagnosis of lymphoma, type of lymphoma, and early (I and II) or advanced (III and IV) clinical stage.

The patients in both groups received the standard medical care from the tertiary care center. The patients in the case group were evaluated by the Departments of Internal Medicine, Gastroenterology and Hematology, and the patients in the control group were evaluated by the Departments of Internal Medicine and Hematology. The chemotherapeutic treatment was proposed by the interdisciplinary group, and the final decision was made by the Department of Hematology.

The distribution of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. For the baseline clinical characteristics, descriptive statistics were used, for quantitative variables, mean ± standard deviation or median and (p25-p75) were used according to the distribution, while for qualitative variables, absolute frequencies were used.

Student's t test was used whenever the data had a normal distribution, and Mann-Whitney U test was used when the data distribution was nonparametric. Chi-square or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical data, and Kaplan-Meier curves and log-rank tests were used to evaluate survival. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software package version 25 (International Business Machines, Armonk, NY, United States).

We reviewed 8658 medical records of patients with diagnosis of lymphoma and/or cirrhosis and found 23 patients with a concomitant diagnosis of liver cirrhosis and lymphoma, of whom only 10 patients underwent chemotherapy. These were paired with 20 patients with lymphoma without liver disease to perform the analysis. The flowchart for patient inclusion is shown in Figure 1.

The demographic, clinical and biochemical characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Differences were found, as expected, only in biochemical parameters with changes inherent to cirrhosis compared to the non-cirrhotic population.

| General characteristics | Cases (n = 10) | Controls (n = 20) |

| Female sex | 6 (60) | 12 (60) |

| Age (yr) | 56 ± 14.2 | 57 ± 12.9 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.57 ± 3.44 | 27.30 ± 7.57 |

| Lymphoma type | ||

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 9 (90) | 18 (90) |

| Laboratory data | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.13 ± 2.39 | 11.97 ± 3.18 |

| Platelets (K/μL) | 166.60 ± 143.8a | 293.9 ± 157.6 |

| Leukocytes (K/μL) | 5.4 ± 1.79 | 7.47 ± 3.79 |

| INR | 1.24 ± 0.19b | 1.0 ± 1.0 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.74 ± 1.31a | 0.97 ± 0.75 |

| Direct bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.76 ± 0.82a | 0.27 ± 0.34 |

| ALT (U/L) | 31.82 ± 33.30 | 25.6 ± 13.35 |

| AST (U/L) | 48.50 ± 27.31a | 32.1 ± 16.52 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (U/L) | 210.40 ± 261.2 | 136.40 ± 149.1 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.78 ± 0.69 | 3.3 ± 0.82 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | 132 (130-138) | 137 (132-140) |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.82 ± 0.21 | 1.63 ± 2.25 |

| β-2 Microglobulin (g/dL) | 3.17 ± 1.39 | 3.02 ± 3.08 |

| LDH (U/L) | 198.29 ± 119.81 | 356.5 ± 304.86 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Obesity | 2 (20) | 6 (30) |

| Dyslipidemia | 0 (0) | 4 (20) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3 (30) | 3 (15) |

| Arterial hypertension | 2 (20) | 8 (40) |

| Alcohol consumption | 3 (30) | 5 (25) |

| Tobacco consumption | 5 (50) | 7 (35) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

The etiology and severity of liver disease in the case group are shown in Table 2. The etiologies of liver cirrhosis were hepatitis C virus (HCV) in 5 (50%) patients, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in 2 (20%) patients, alcohol in 1 (10%) patient, autoimmune hepatitis in 1 (10%) patient and cryptogenic in 1 (10%) patient. In relation to the five patients with viral cirrhosis (HCV), four of them were treatment naïve at the time of lymphoma diagnosis, and one of them had been treated previously and achieved sustained virologic response before the onset of lymphoma. Only one treatment naïve patient could receive antiviral treatment after chemotherapy. Regarding liver disease, eight (80%) patients were in a decompensated state of cirrhosis. The events of decompensation in the population included ascites in 6 (60%) patients, variceal bleeding in 5 (50%) patients, jaundice in 1 (10%) patient, hepatic encephalopathy in 1 (10%) patient and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in 1 (10%) patient. The median score according to the CTP scale was 7.5 points, and the distribution for classes A/B/C of this scoring system was n = 2, 6, 2, respectively. The mean score according to the MELD prognostic index was 11.5 ± 4.50 points, and MELD-Na was 16.5 ± 5.12 points. The median time between the diagnosis of cirrhosis and lymphoma was 2.16 years, with a range between the same diagnostic time and 8.6 years after the diagnosis of cirrhosis.

| Characteristics of patients with cirrhosis | Cases (n = 10) |

| Etiologies of cirrhosis | |

| HCV | 5 (50) |

| NAFLD | 2 (20) |

| Alcohol | 1 (10) |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | 1 (10) |

| Cryptogenic | 1 (10) |

| States of cirrhosis | |

| Compensated | 2 (20) |

| Decompensated | 8 (80) |

| Events of decompensation | |

| Jaundice | 1 (10) |

| Variceal bleeding | 5 (50) |

| Ascites | 6 (60) |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | 1 (10) |

| Encephalopathy | 1 (10) |

| CTP score | 7.5 (6.75-9.25) |

| CTP class A | 2 (20) |

| CTP class B | 6 (60) |

| CTP class C | 2 (20) |

| MELD | 11.5 ± 4.50 |

| MELD-Na | 16.5 ± 5.12 |

The characteristics of patients with lymphoma in both groups are shown in Table 3. Non-Hodgkin's lymphomas were the most common type (90%, n = 27), and within these, the predominant histologic subtype was diffuse large B cell (80%) in 24 patients (7 cases and 17 controls). In the case group, there was only one patient with Hodgkin's lymphoma with histological variety of lymphocytic depletion. In relation to the clinical stage, there were no significant differences between the two groups. The severity, according to the different prognostic scales validated for the different types of lymphoma, was greater in patients with cirrhosis [International Prognostic Index (IPI): 3 vs 2, P = 0.049]. The quality of life according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale of performance status and the presence of B symptoms was similar between both groups. Finally, we observed that from the established risk factors for the development of lymphoma, the case group had a higher prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection (3 vs 0, P = 0.030).

| Characteristics of lymphomas | Cases (n = 10) | Controls (n = 20) |

| Lymphoma type and subtypes | ||

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 9 (90) | 18 (90) |

| Diffuse large B cell | 7 (70) | 17 (85) |

| Follicular | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Others | 1 (10) | 1 (5) |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 1 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Nodular sclerosis | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Lymphocyte predominant | 0 (0) | 1 (5) |

| Lymphocyte depleted | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Clinical stages | ||

| I | 1 (10) | 4 (20) |

| II | 2 (20) | 3 (15) |

| III | 1 (10) | 6 (30) |

| IV | 6 (60) | 7 (35) |

| Extra nodal involvement | 6 (60) | 9 (45) |

| Prognostic scale | ||

| IPI score | 3 (2.5-3)a | 2 (1-3) |

| FLIPI score | 3 | - |

| IPS score | 3 | 2.5 |

| ECOG Performance Status | 2 (1-2.25) | 2 (1-2) |

| B symptoms | ||

| Fever | 3 (30) | 6 (30) |

| Weight loss | 9 (90) | 11 (55) |

| Nocturnal diaphoresis | 4 (40) | 6 (30) |

| Helicobacter pylori | 3 (30)a | 0 (0) |

The type of chemotherapy and its outcomes in the study population are described in Table 4. The drugs used in the most relevant chemotherapy regimens were very similar between both groups. Chemotherapy was adjusted more frequently in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma than in patients with lymphoma alone (50% and 5%, respectively, P = 0.009). In relation to complications derived from chemotherapy, there were similarities between both groups (80% vs 90%, P = 0.407); however, non-hematological toxicities were more frequent in the case group (30% vs 0%, P = 0.030). Regarding non-hematological toxicities, in the case group, 1 patient (10%) presented acute kidney injury AKIN II, 1 patient (10%) presented atypical pneumonia, and 1 patient (10%) had acute non-infectious diarrhea grade II. In the control group, 18 (90%) patients had hematological toxicity, and there was no other type of toxicity.

| Chemotherapy | Cases (n = 10) | Controls (n = 20) |

| Drugs | ||

| Rituximab | 5 (50) | 9 (45) |

| Cyclophosphamide | 8 (80) | 17 (85) |

| Doxorubicin | 5 (50) | 15 (75) |

| Vincristine | 8 (80) | 17 (85) |

| Prednisone | 6 (60) | 17 (85) |

| Bleomycin | 2 (20) | 3 (15) |

| Dacarbazine | 1 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Etoposide | 4 (40) | 3 (15) |

| Vinblastine | 0 (0) | 2 (10) |

| Methotrexate | 1 (10) | 4 (20) |

| Ifosfamide | 2 (20) | 2 (10) |

| Carboplatin | 2 (20) | 2 (10) |

| Dexamethasone | 2 (20) | 1 (5) |

| Others | 2 (20) | 4 (20) |

| Chemotherapy adjustment | 5 (50)b | 1 (5) |

| Radiotherapy | 1 (10) | 2 (10) |

| Treatment response | ||

| Complete response | 4 (40) | 10 (50) |

| Partial response | 4 (40) | 9 (45) |

| Stable disease | 2 (20) | 1 (5) |

| Disease progression | 5 (50) | 5 (25) |

| Relapse | 2 (20) | 3 (15) |

| Complications | 8 (80) | 18 (90) |

| Hematologic toxicity | 6 (60) | 18 (90) |

| Gastrointestinal toxicity | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Renal toxicity | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Infectious toxicity | 1 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Decompensating events | 1 (10) | - |

| Death | 7 (70) | 8 (40) |

Among the complications derived from chemotherapy, we found that most were hematological toxicities, mainly anemia. On the other hand, it was remarkable that patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis had a trend to develop less hematological toxicity than the controls (cases 60% vs controls 90%, P = 0.141), which may be related to the adjustment in chemotherapy. Within hepatic toxicities, only one decompensating event (hepatic encephalopathy) occurred in one patient, which had implications in the continuation of chemotherapeutic treatment but did not directly correlate with the cause of death. Other important complications are infections, which were higher in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma, probably because of the susceptibility of patients due to depletion of immunity, in addition to the state of decompensation of the patients.

Treatment response was evaluated according to international recommendations and divided into complete response (4 cases vs 10 controls, P = 0.488), partial response (4 cases vs 9 controls, P = 1.0), stable disease (2 cases vs 1 controls, P = 0.251), disease progression (5 cases vs 5 controls, P = 0.231) and relapse (2 cases vs 3 controls, P = 1.0). The number of deaths in patients with cirrhosis was 7 (70%), and in patients without liver disease, there were 8 deaths (40%), although it was not significant (P = 0.209).

The survival of patients in both groups can be seen in Figure 2 in the Kaplan-Meier curve. Table 5 shows that the mean survival of patients with lymphoma without liver disease was 56 wk, while in patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis, it was 30 weeks on average, although no statistically significant difference (P = 0.269) was observed, most likely due to the sample size.

| Population | Mean |

| Case group (wk) | 30.66 ± 30.05 |

| Control group (wk) | 56.46 ± 51.15 |

| Global (wk) | 44.56 ± 43.76 |

Liver cirrhosis is a frequent disease worldwide and is the 14th cause of mortality globally[18]. In addition, these patients have risk factors related both to the development of cirrhosis (such as HCV infection) and disease per se (alterations in immune surveillance), which confers an increased risk of developing neoplastic diseases, including lymphomas[19-21]. Due to the progressive increase in hepatic diseases such as NAFLD, it is expected that in the next years, there will be more cases of cirrhosis, and concomitantly, these patients may develop extrahepatic tumors such as lymphoma, making it necessary to know how to approach these patients with both conditions.

Chronic liver disease (especially cirrhosis) poses multiple challenges when deciding the type of chemotherapy due to clinical characteristics of these patients, including hypersplenism, with a lower margin of safety for hematological complications such as thrombocytopenia, anemia, and leukopenia; the elevation in bilirubin levels is itself one of the few parameters recommended for chemotherapy adjustment, but which may be biased in interpretation in patients with cholestatic diseases such as primary biliary cholangitis; and finally, the patient's general condition, in which cachexia, deconditioning, low protein/albumin levels and decreased liver function are observed.

Currently, the recommendations issued by different experts are based solely on the evaluation of liver function as the main determinant of its prognosis. Patients with compensated cirrhosis, whose prognosis they consider to be defined primarily by cancer, are considered for chemotherapy. On the other hand, decompensated patients, whose prognosis is estimated to be determined by liver disease, are not considered for treatment because experts believe it may further worsen liver function and only provide supportive care. While these factors should be taken into account, there is no strong recommendation that more objectively delimits the optimal parameters for offering chemotherapy treatment, which gives the patient a greater survival rate without neglecting their safety.

In the present study, expected differences between cases and controls were observed in biochemical parameters, including liver function tests abnormalities, high INR and low platelet levels. These differences are secondary to liver disease itself and portal hypertension leading to hypersplenism.

It is noteworthy that most (80%) of the patients with cirrhosis in the study were in a decompensated phase of the disease. This is of utmost importance, since according to the current expert recommendations, these patients would be excluded from oncological treatment. However, despite decompensation, treatment with chemotherapy is feasible in this population without affecting safety or presenting greater toxicity or adverse events.

Regarding the general characteristics of lymphomas, the majority (66%) of patients in the study were diagnosed at advanced stages (clinical stage III and IV) of the disease, most patients had B symptoms, with weight loss being the most common (66%) and one of the main reasons for seeking medical care. In the case of diffuse large B cell non-Hodgkin's lymphomas, the IPI was significantly higher in cases than in controls (cases 3 vs 2 controls, P = 0.049), maybe due to increased extra nodal involvement.

Finally, it should be noted that in relation to the risk factors associated with the development of lymphoma, the group of patients with liver disease had a higher incidence of a history of H. pylori infection, which has been reported in previous studies. These studies have shown an increased risk of H. pylori infection in patients with liver cirrhosis, especially in those with viral etiology (HCV and hepatitis B virus), most likely due to impaired immune function[22,23].

In relation to survival, as seen in the Kaplan-Meier curves, patients with cirrhosis had a lower survival rate (almost half compared to those without liver disease), although it failed to reach statistical significance, probably due to the sample size; however, despite the extensive search of nearly 9000 patients (including those with cirrhosis and those with lymphoma), only the cases described in this study were found.

Even though the presence of portal hypertension-related complications contributes to the increased mortality in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma, this should not preclude the evaluation and treatment of hematological disease with curative intentions. Regarding this, in the group of cases, we found a CTP class C patient who received non-adjusted chemotherapy and had an overall survival of 82 week to finally receive a liver transplant. This is important because it shows that even in decompensated patients, curative treatment is feasible and not confining the patient to palliative treatment only.

It is important to note that chemotherapy is usually adjusted with the value of bilirubin; therefore, cirrhotic patients, having high bilirubin levels from the liver disease itself, an adjustment is often made that may even contraindicate certain drugs and are not given a complete regimen that they could tolerate.

Although there are clinical characteristics that make patients with cirrhosis not the best candidates to receive chemotherapy, in this study it was observed that this treatment is feasible even in decompensated patients, observing greater renal, gastrointestinal and infectious toxicity. None of these complications caused death, which will help to more closely monitor this type of complications in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma treated with chemotherapy, as well as to develop more studies to establish the safety margin of these drugs and to adequately define the adjustment and effectiveness of chemotherapy.

It is important to emphasize that currently, there are no international guidelines on the management of these patients, and in the field of clinical research, there is very little work to develop scientific evidence in this regard. Although several positions have been proposed by different experts in the field, they do not have satisfactory clinical validation. The absence of randomized clinical trials with this patient group means that the choice of treatment is not evidence-based. Therefore, it is important that in the future, clinical trials on chemotherapy treatments that include patients with cirrhosis are designed to generate recommendations based on the evidence and to know their outcomes.

This is the first study evaluating the clinical characteristics, the type of chemotherapy, the response and complications arising from the treatment, and survival in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma.

The strengths of the study include an adequate methodology and the fact that all patients had a thorough evaluation of the characteristics of cirrhosis and its complications, sometimes in other studies overlooked when evaluated only by one type of specialist. In this study, the type and adjustment of chemotherapy was decided by a multidisciplinary team (Internal Medicine, Hematology, Gastroenterology and Hepatology) according to the available guidelines in a non-cirrhotic population.

This study has some limitations; first, being a retrospective study, it has an inherent risk of information and selection bias. Some of the bias that may be present in this study may be due to the fact that we analyzed patients from a large time period, which could cause differences in the available treatments. Additionally, we excluded patients who refused chemotherapy or died before receiving it, which could be considered as bias; however, since we wanted to evaluate the response to chemotherapy, it was considered necessary to exclude them for the purpose of the study. On the other hand, the number of cases (lymphoma and cirrhosis) is relatively small, but despite that, the present study has the largest number of patients with both diseases than any other, since previously conducted studies included only case reports or case series with a maximum of two patients. Furthermore, the fact that all patients from our center with concomitant diseases in an 18-year period were included is to be noted, as the small sample size is due to the low frequency of the cases, which clearly supports the case-control methodology.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the clinical characteristics of patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis are similar to those with lymphoma, except for some changes inherent to cirrhosis and portal hypertension. Additionally, it may be possible to administer chemotherapy regimens in selected cirrhotic patients, regardless of their severity or even in decompensated patients, obtaining acceptable treatment outcomes (response to treatment and complications), always closely monitoring their toxicity.

A significant number of patients with liver cirrhosis concomitantly develop some type of solid or hematological cancer, including lymphoma. Treatment of patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis is challenging for physicians due to the clinical characteristics related to cirrhosis and lack of scientific evidence, limiting the use of chemotherapy. Currently, experts recommend only offering oncological treatment to patients with compensated cirrhosis and the best supportive care to those in a decompensated state.

The treatment of lymphomas in patients with cirrhosis is a difficult task, and even the involvement of a multidisciplinary team may still not be enough, considering the lack of published literature about clinical outcomes, the narrow therapeutic index of the drugs and the safety issues that are typical in these patients. A study that evaluates treatment with chemotherapy in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma is necessary to address this knowledge gap.

To evaluate the clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes (type of chemotherapy regimen, response rate and complications derived from it, and survival) in patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma treated with chemotherapy to generate scientific evidence in this regard.

This was a case-control study conducted at a tertiary care center in Mexico. Data was recorded from medical files from 2000 through 2018, and from 8658 possible candidates with cirrhosis and/or lymphoma, only 23 cases had both diseases concomitantly; 10 patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma (cases) met the selection criteria and were included, and 20 patients with lymphoma (controls) were included and matched according to age, sex, and date of diagnosis, type and clinical stage of lymphoma. All patients received treatment with chemotherapy. For statistical analysis, descriptive statistics, Shapiro-Wilk test, Mann-Whitney U test, chi-square test and Fisher's exact test were used. Survival was evaluated using Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test.

There were differences in biochemical variables inherent to liver disease and portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. The most frequent etiology of cirrhosis was hepatitis C virus (50%); 80% were decompensated, the median Child-Turcotte-Pugh score was 7.5 (6.75-9.25), and mean Model for End-stage Liver Disease was 11.5 ± 4.50. Regarding lymphomas, non-Hodgkin's were the most common (90%), and diffuse large B cell subtype was the most frequent, with a higher International Prognostic Index in the cases (3 vs 2, P = 0.049). The chemotherapy regimens had to be adjusted more frequently in the case group (50% vs 5%, P = 0.009). The complications derived from chemotherapy were similar between both groups (80% vs 90%, P = 0.407); however, non-hematological toxicities were more common in the case group (30% vs 0%, P = 0.030). There was no difference in the response to treatment between groups. Survival was higher in the control group (56 wk vs 30 wk, P = 0.269), although it did not show statistical significance. This study included mainly decompensated patients with cirrhosis and lymphoma with acceptable treatment outcomes.

The clinical characteristics of patients with lymphoma and cirrhosis are similar to those with lymphoma, except for some changes inherent to cirrhosis. It may be possible to administer chemotherapy in selected cirrhotic patients, regardless of their severity, obtaining satisfactory clinical outcomes.

We propose that lymphoma treatment can be provided in patients with cirrhosis at any clinical state without neglecting their safety, although more prospective clinical trials are needed to generate stronger recommendations and better establish safety margins.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Mexico

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Dourakis SP, Takahashi T, Tarantino G, Zapater P S-Editor: Ma RY L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, Ferlay J, Lortet-Tieulent J, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:87-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18694] [Cited by in RCA: 21363] [Article Influence: 2136.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 2. | Tsochatzis EA, Bosch J, Burroughs AK. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet. 2014;383:1749-1761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1139] [Cited by in RCA: 1311] [Article Influence: 119.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2018;391:1301-1314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2800] [Cited by in RCA: 4092] [Article Influence: 584.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 4. | Kalaitzakis E, Gunnarsdottir SA, Josefsson A, Björnsson E. Increased risk for malignant neoplasms among patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:168-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Carbone D. Smoking and cancer. Am J Med. 1992;93:13S-17S. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Dam MK, Flensborg-Madsen T, Eliasen M, Becker U, Tolstrup JS. Smoking and risk of liver cirrhosis: a population-based cohort study. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:585-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Pöschl G, Seitz HK. Alcohol and cancer. Alcohol Alcohol. 2004;39:155-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 371] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 17.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Grant BF, Dufour MC, Harford TC. Epidemiology of alcoholic liver disease. Semin Liver Dis. 1988;8:12-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 171] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bugianesi E. Review article: steatosis, the metabolic syndrome and cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22 Suppl 2:40-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Streba LA, Vere CC, Rogoveanu I, Streba CT. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, metabolic risk factors, and hepatocellular carcinoma: an open question. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:4103-4110. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | National Institute of Health. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Fact sheets. Available from: URL: https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/. |

| 12. | Ansell SM. Hodgkin Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1574-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ansell SM. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Diagnosis and Treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:1152-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pinter M, Trauner M, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Sieghart W. Cancer and liver cirrhosis: implications on prognosis and management. ESMO Open. 2016;1:e000042. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 202] [Article Influence: 22.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Parker SM, Hyder MA, Fesler MJ. Bendamustine and rituximab for indolent B-cell non-hodgkin lymphoma in patients with compensated hepatitis C cirrhosis: a case series. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:e15-e17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Siba Y, Obiokoye K, Ferstenberg R, Robilotti J, Culpepper-Morgan J. Case report of acute-on-chronic liver failure secondary to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16774-16778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Batur A, Odev K. Primary lymphoma of the gallbladder accompanied by cirrhosis: CT and MRI findings. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Mathers C, Lopez A, Murray C, Lopez A, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: data, methods, and results for 2001. Lopez A, Mathers C, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL. Global burden of disease and risk factors. Washington (DC): World Bank 2006; 45-93. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Negri E, Little D, Boiocchi M, La Vecchia C, Franceschi S. B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and hepatitis C virus infection: a systematic review. Int J Cancer. 2004;111:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sorensen HT, Friis S, Olsen JH, Thulstrup AM, Mellemkjaer L, Linet M, Trichopoulos D, Vilstrup H, Olsen J. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998;28:921-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 237] [Cited by in RCA: 230] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lombardo L, Rota Scalabrini D, Vineis P, De La Pierre M. Malignant lymphoproliferative disorders in liver cirrhosis. Ann Oncol. 1993;4:245-250. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Feng H, Zhou X, Zhang G. Association between cirrhosis and Helicobacter pylori infection: a meta-analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:1309-1319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pogorzelska J, Łapińska M, Kalinowska A, Łapiński TW, Flisiak R. Helicobacter pylori infection among patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29:1161-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |