Published online Dec 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i12.1314

Peer-review started: May 25, 2020

First decision: June 4, 2020

Revised: August 13, 2020

Accepted: November 4, 2020

Article in press: November 4, 2020

Published online: December 27, 2020

Processing time: 205 Days and 18 Hours

In the last few years we have witnessed a revolution in the treatment of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. With the introduction of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs), sustained virological response (SVR) is achieved in more than 95% of the patients. The focus is now being turned to the global targets set by the World Health Organization, with the aim of achieving HCV elimination by 2030. Prison inmates constitute one of the high-risk groups, and receive treatment less frequently due to several barriers in access to health care.

To describe the management and follow-up of a cohort of HCV monoinfected patients treated with DAA in the prison setting, where tertial referral liver center specialists locally provide, on-site assessment and treatment for the prisoners.

A prospective observational study was conducted from April 2017 to March 2020, which included all HCV monoinfected prison inmates in the largest Northern Portugal prison. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data, as well as transient elastography measurements, were collected onsite by the medical team and prospectively recorded. Patients were treated with DAA according to international guidelines. The primary endpoint was SVR at post-treatment week 12.

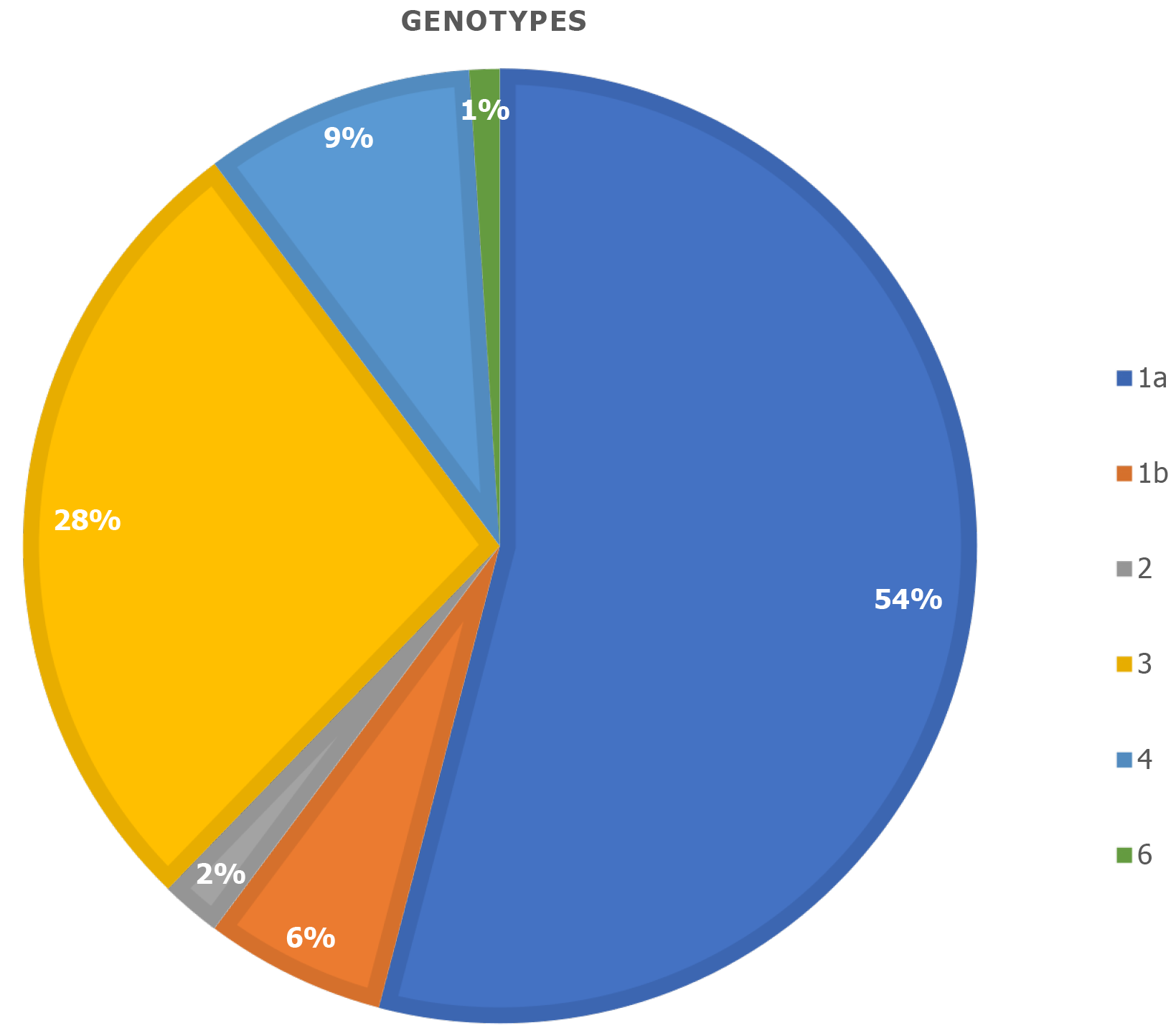

There were 98 monoinfected HCV male inmates (mean age, 42.7 ± 8.6 years) included in the analysis. Injecting drugs or tattooing were reported in 74.5%, with 38.8% of the latter being done in prison. Alcohol consumption of more than 30 g/d was referred in 69.4%. The most prevalent genotype was 1a (54.1%), followed by 3 (27.6%), 4 (9.2%) and 1b (6.1%). Pretreatment fibrosis degree was mild-to-moderate (F0-F2) in 77.6% and severe in 22.4% (F3-F4). Treatment regimens chosen were: 45.9% elbasvir/grazoprevir, 29.6% sofosbuvir/velpatasvir, and 12.2% sofosbuvir/ledispavir and glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. No major adverse events were observed. SVR at post-treatment week 12 was 99%.

In a population considered to be both hard-to-access and a cornerstone for HCV elimination, the onsite evaluation and treatment of HCV-infected prisoners, achieved an exceptional highly effective success rate. This type of collaborative program should be considered to be expanded, to support hepatitis C elimination efforts.

Core Tip: Hepatitis C is a curable infectious disease with high cure rates reaching almost 100% with the use of direct-acting antiviral agents. The World Health Organization defined the aim of achieving hepatitis C virus elimination by 2030. In the first phase, patients identified with hepatitis C virus infection were treated. Although, to achieve this ambitious goal, we had to reach difficult to access groups, such as persons who inject drugs (PWID) and prisoners. We developed a strategy where a medical team (2-3 doctors) from the hospital went to prison and was responsible for the outpatient clinics, liver elastography, and giving the medication on-site, increasing access to care by avoiding any need to move the patients outside the prison. This was so successful, reaching 99% of sustained virological response in a difficult to treat cohort, that a national program was created implementing our strategy. Therefore, in Portugal, every prisoner has access to treatment inside the prison.

- Citation: Gaspar R, Liberal R, Tavares J, Morgado R, Macedo G. HIPPOCRATES® project: A proof of concept of a collaborative program for hepatitis C virus micro-elimination in a prison setting. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(12): 1314-1325

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i12/1314.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i12.1314

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is recognized as the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, being one of the major global health problems. The prevalence of HCV infection ranges from 0.5% in Western Europe and 1.3% in United States to 2.5 in Southern Europe and 6% in Eastern Europe[1]. According to the last report from World Health Organization (WHO), about 71 million people are suffering from chronic HCV infection, with almost 400000 deaths due to cirrhosis or liver cancer[2-5]. Moreover, it is still the most common indication for liver transplantation. Management of HCV infection places a large burden on local health systems due to social and economic charges[5].

In the last few years, we have witnessed a major revolution in the treatment of HCV infection. The introduction of direct-acting antiviral agents (DAAs) resulted in fewer side effects, shorter regimen treatments, and higher rates of sustained virological response (SVR). Because cure is attainable in almost all patients, the WHO defined ambitious targets to be achieved by 2030, namely HCV elimination, with 65% reduction in liver-related deaths, 90% reduction of new infections, and 90% of patients with viral hepatitis infections being diagnosed[5].

However, HCV elimination poses several logistic and political challenges: Most health systems are not prepared to deal with the huge task of HCV testing and treatment, and, many times, it is difficult to convince health authorities to provide human and financial resources so that HCV elimination could be a realistic goal. Recently, the concept of micro-elimination has emerged, where the main focus is tackling specific individual populations, creating an organized plan to overcome the known barriers, and achieving both high levels of diagnosis and treatment, choosing also the best interventions in accordance with that population's needs.

This strategy is going to target well-recognized high-risk populations such as people who injected drugs, homeless people, and prisoners, all of whom are typically not well engaged with specialist care[6,7].

Prisons are considered a high-risk environment with a population characterized by risky behaviors such as unprotected sexual intercourse, tattooing, and injecting drug use[3]. At the same time they also provide a unique opportunity to scale up hepatitis C treatment[8]. It is estimated that the prevalence of HCV infection in prisons is 10 to 20 times higher than that of the average population. The reported prevalence of HCV infection in prisoners ranges from 15.4% in Western Europe to 20.7% in Eastern Europe[9,10]. The correctional system may be considered a public health opportunity to treat these patients[11] for a variety of reasons: Improved adherence due to daily staff distribution of medication, limited access to drugs and alcohol, and monitoring of possible side effects[12]. Although treatment of HCV infection in the correctional systems seems necessary to achieve the goal of HCV elimination by 2030, there are few reports about the management of HCV in prison, particularly in the DAA era.

The aim of this study is to describe an innovative program of diagnosing and treating HCV monoinfected patients within the prison setting, the HIPPOCRATES® (Hepatitis C In-PrisonProgram fOr enhancing Cure RATES) Project, and evaluate its performance in curing this infection, assessing SVR at post treatment week 12 (SVR 12).

HCV is recognized as the leading cause of chronic liver disease worldwide, being one of the major global health problems. The prevalence of HCV infection ranges from 0.5% in Western Europe and 1.3% in United States to 2.5 in Southern Europe and 6% in Eastern Europe[1]. According to the last report from WHO, about 71 million people are suffering for chronic HCV infection, with almost 400000 deaths due to cirrhosis or liver cancer[2-5]. Moreover, it is still the most common indication for liver transplantation. Management of HCV infection places a large burden on local health systems due to social and economic charges[5].

In the last few years, we have witnessed a major revolution in the treatment of HCV infection. The introduction of DAA resulted in fewer side effects, shorter regimen treatments and higher rates of SVR. Because cure is attainable in almost all patients, the WHO defined ambitious targets to be achieved by 2030, namely HCV elimination, with 65% reduction in liver-related deaths, 90% reduction of new infections, and 90% of patients with viral hepatitis infections being diagnosed[5].

However, HCV elimination poses several logistic and political challenges: Most health systems are not prepared to deal with the huge task of HCV testing and treatment, and many times, it is difficult to convince health authorities to provide human and financial resources so that HCV elimination could be a realistic goal. Recently, the concept of micro-elimination has emerged, where the main focus is tackling specific individual populations, creating an organized plan to overcome the known barriers and achieve both high levels of diagnosis and treatment, choosing also the best interventions in accordance to that population's needs.

This strategy is going to target well-recognized high-risk populations, such as people who injected drugs, homeless people and prisoners, typically not well engaged with specialist care[6,7].

Prisons are considered a high-risk environment with a population characterized by risky behaviors such as unprotected sexual intercourse, tattooing and injecting drug use[3]. At the same time they also provide a unique opportunity to scale up hepatitis C treatment[8]. It is estimated that the prevalence of HCV infection in prisons is 10 to 20 times higher compared to that of the average population. Reported prevalence of HCV infection in prisoners range from 15.4% in Western Europe to 20.7% in Eastern Europe[9,10]. The correctional system may be considered a public health opportunity to treat these patients[11] for a variety of reasons: Improved adherence due to daily staff distribution of medication, limited access to drugs and alcohol, and monitoring of possible side effects[12]. Although treatment of HCV infection in the correctional systems seems necessary to achieve the goal of HCV elimination by 2030, there are few reports about the management of HCV in prison, particularly in DAA era.

The aim of this study is to describe an innovative program of diagnosing and treating HCV monoinfected patients within the prison setting, the HIPPOCRATES® Project, and evaluate its performance in curing this infection, assessing SVR 12.

Porto’s correctional system is an exclusive male prison located in Porto, the second largest city of Portugal. It is the largest prison in the Northern Portugal, having the capacity for 1200 inmates. The Medical Department has one treatment room, four outpatient clinic rooms, and a ward with the capacity for six patients. Personnel staff comprises one permanent doctor and four nurses.

All inmates were tested for hepatitis B virus, HCV, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) on admission and there was no refusal to be screened. All anti-HCV antibody positive inmates were tested for HCV RNA, even in cases of previous treatment or negative RNA on previous admissions due to the possibility of reinfection in this high-risk population. Viral load and genotype were determined according to international guidelines.

To be eligible for treatment, prisoners had to be ≥ 18-years-old, have evidence of active chronic hepatitis C with a recent detectable serum HCV RNA, and have an adequate sentence duration to facilitate complete hepatitis C treatment while incarcerated (between 8 and 12 wk, depending on the chosen treatment). However, it was not a requirement that prisoners remained in prison till SVR 12, and those who were released earlier were provided with their remaining medication to complete treatment in the community and had follow-up scheduled in the hospital’s Hepatology outpatient clinic.

Following identification, HCV monoinfected patients were referred by the Prison doctor to the Liver specialist team. This medical team, from the Gastroenterology Department, consisted of three Hepatologists from Centro Hospitalar São João, the largest liver center in the north of the country. All co-infected patients were treated by the Infectious Disease team.

Those hospital doctors visited once weekly the prison, where all clinical procedures were performed, in coordination with the prison doctor.

For each patient, we had scheduled three clinical visits, for a total of 302. In the first one, careful medical history and demographics were taken including age, place of birth, weight and height, medication, history of previous blood transfusions, tattooing, drugs (injected or inhaled), alcohol and tobacco consumption. Patients were also asked about the exact time of HCV infection diagnosis, as well as previous treatments. During the first visit, a transient liver elastography was performed onsite. After gathering clinical, laboratory, and virological data together with the fibrosis stage, treatment regimen and duration was decided by the medical team and requested to the central pharmacy.

In the second appointment, when treatment was already available, the expected efficacy and possible side effects were again explained. For those patients who decided to participate in this program, treatment started on the day after. The prison staff was responsible for distributing the DAAs to our patients, and were instructed by the medical team before the beginning of the program. They were already previously in charge of distributing the opioid substitution therapy.

The third outpatient visit was performed 12 wk after the end of treatment to inform the patient about SVR. All patients received extensive counseling and education about harmful practices potentially leading to reinfection such as tattooing, sharing needles or unprotected sexual intercourse, and they were instructed to change their own usual hygienic habits from the beginning of treatment. We established a viral hepatitis education program for prisoners and prison staff, including drug service providers and correctional officers, to support clinical service. Prisoners with hepatitis C and cirrhosis were enrolled in surveillance programs for hepatocellular carcinoma and esophageal varices, as recommended by consensus guidelines[13].

All the procedures were performed by the same three hepatologists and any problems concerning these patients were seen by the prison's doctor and reported to the hospital team.

Blood samples were all taken in the prison setting by a special team of nurses. Every patient had laboratory data at three-time points: (1) Before starting the treatment; (2) At the end of treatment; and (3) 12 wk after the end of treatment to assess SVR 12. At all time points, full blood count, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), alkaline phosphatase, total and direct bilirubin, albumin, urea, and creatinine were requested. In addition, first and last blood samples were analyzed for iron, transferrin and ferritin, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, alpha-fetoprotein, international normalized ratio, hepatitis B surface (HBs) antigen, HBs antibody, hepatitis B core antibody, and HIV.

The degree of fibrosis was evaluated using the portable Fibroscan 430 mini model from Echosensâ (owned by our department), performed in the prison by the gastroenterology medical team, and classified according to Metavir classification[14]. Only procedures with at least 10 valid measurements, an interquartile range/median ratio of less than 30%, and a success rate of at least 60% were included. The median value of liver stiffness was recorded in kPa. All procedures were performed by well-experienced and well-trained investigators.

The treatment for each patient was discussed within the medical team based on the laboratory data and liver fibrosis stage, and decided according to international guidelines[15].

SVR 12 was defined as having an undetectable HCV RNA test at least 12 wk after the end of treatment.

Continuous variables are expressed as median (range). Categorical variables are reported as absolute (n) or relative frequencies (%). Analysis of variance was used to compare the differences in variable between groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SPSS 21.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, United States).

This study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Centro Hospitalar São João and Porto's correctional system. Informed consent was obtained from each patient before each treatment.

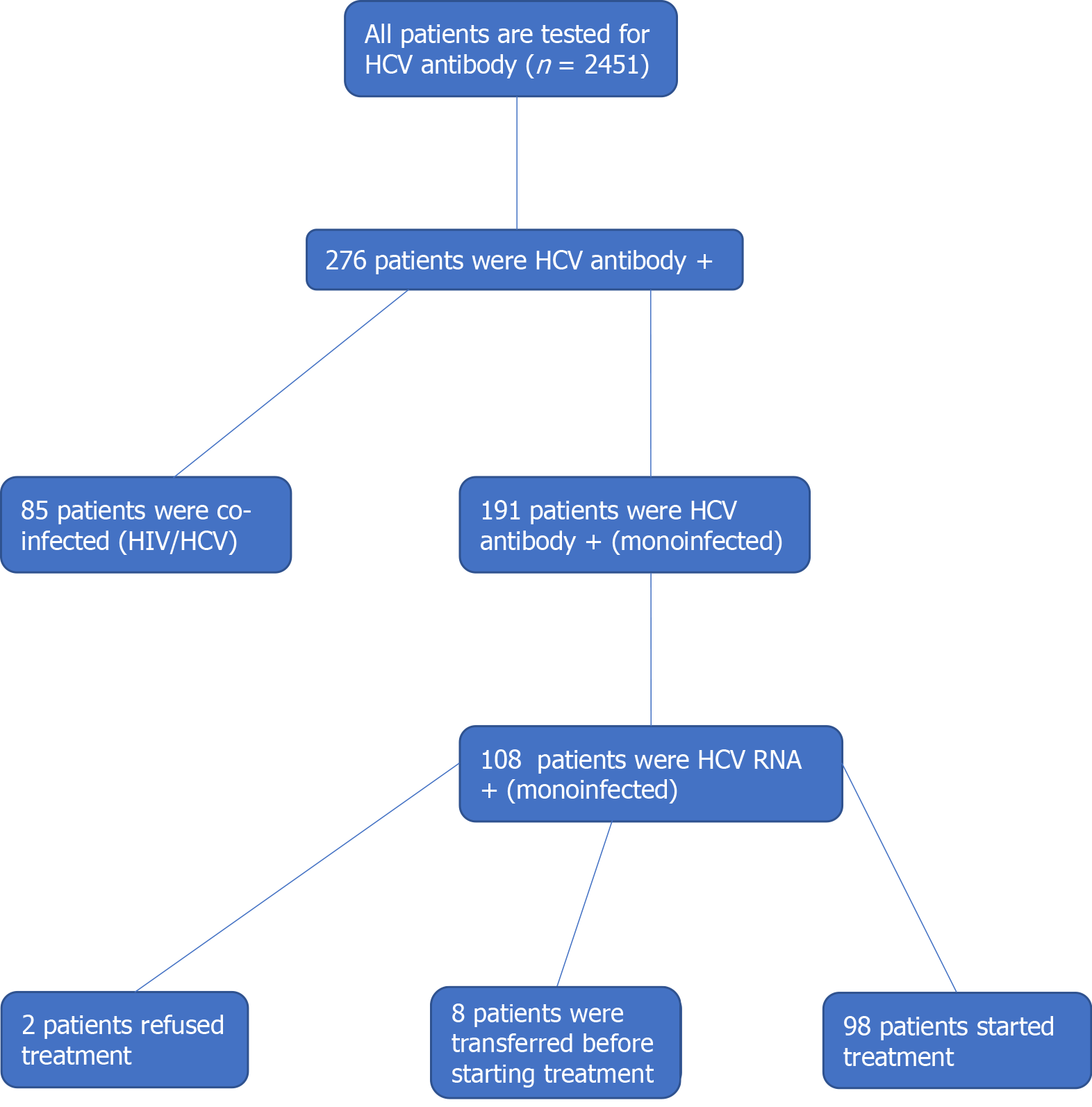

Screening of 2451 inmates resulted in 276 prisoners (11.3%) positive for anti-HCV antibody and negative for HIV. Among them, 27685 patients were co-infected HCV/HIV patients and 191 were only HCV-antibody positive. From the 191 patients, 108 prisoners tested positive for HCV RNA, resulting in a prevalence of ongoing infection of 4.4%. Two patients refused to participate in the project and eight patients were transferred to another institution before starting the treatment. The selection of cases for treatment is summarized in Figure 1.

The mean age of the final group of 98 patients was 42.7 ± 8.6 years (Table 1). All patients were Caucasian and had a mean body mass index of 24.7 ± 3.2.

| Prisoners characteristics | n (%) |

| Age | |

| 18-29 yr | 7 (7.1) |

| 30-39 yr | 22 (22.5) |

| 40-49 yr | 47 (47.9) |

| 50+ yr | 22 (22.5) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean | 24.7 ± 3.2 |

| HCV genotype | |

| 1a | 53 (54.1) |

| 1b | 6 (6.1) |

| 2 | 2 (2.0) |

| 3 | 27 (27.6) |

| 4 | 9 (9.2) |

| 6 | 1 (1.0) |

| Tattooing | |

| No | 25 (25.5) |

| Made in prison | 38 (38.8) |

| Made outside prison | 68 (69.4) |

| Illicit drug use | |

| No | 5 (5.1) |

| Ever smoked heroin/marijuana only | 93 (94.9) |

| Inject drugs | 73 (74.5) |

| Smoker | |

| No | 9 (9.2) |

| Yes, < 10 cigarettes per day | 27 (27,6) |

| Yes, > 10 cigarettes per day and < 20 | 31 (31,6) |

| Yes, > 20 cigarettes per day | 31 (31.6) |

| Alcohol consumption | |

| No | 22 (22.4) |

| Yes, < 30 g day of alcohol | 8 (8.2) |

| Yes, 30 g day of alcohol and < 60 g | 13 (13.3) |

| Yes, 60 g day of alcohol | 55 (56.1) |

| Medication | |

| Opiate substitution therapy | 26 (26.5) |

| Antidepressants | 40 (40.8) |

| Benzodiazepines | 69 (70.4) |

Regarding risk factors for acquiring HCV infection, 9.2% had a previous history of blood transfusions, 74.5% were injecting drug users, and 74.5% had tattoos (38.8% of them were done in the prison setting). The vast majority (94.9%) also reported previous history of smoked drugs (mostly cocaine and cannabis). Active smoking was established in 90.8%, while 77.6% admitted daily alcohol consumption (more than 30 mg/d in 69.4%). Regular medication consisted of benzodiazepines in 70.4% (n = 69), methadone in 26.5% (n = 26), and antidepressants in 40.8% (n = 40). Clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

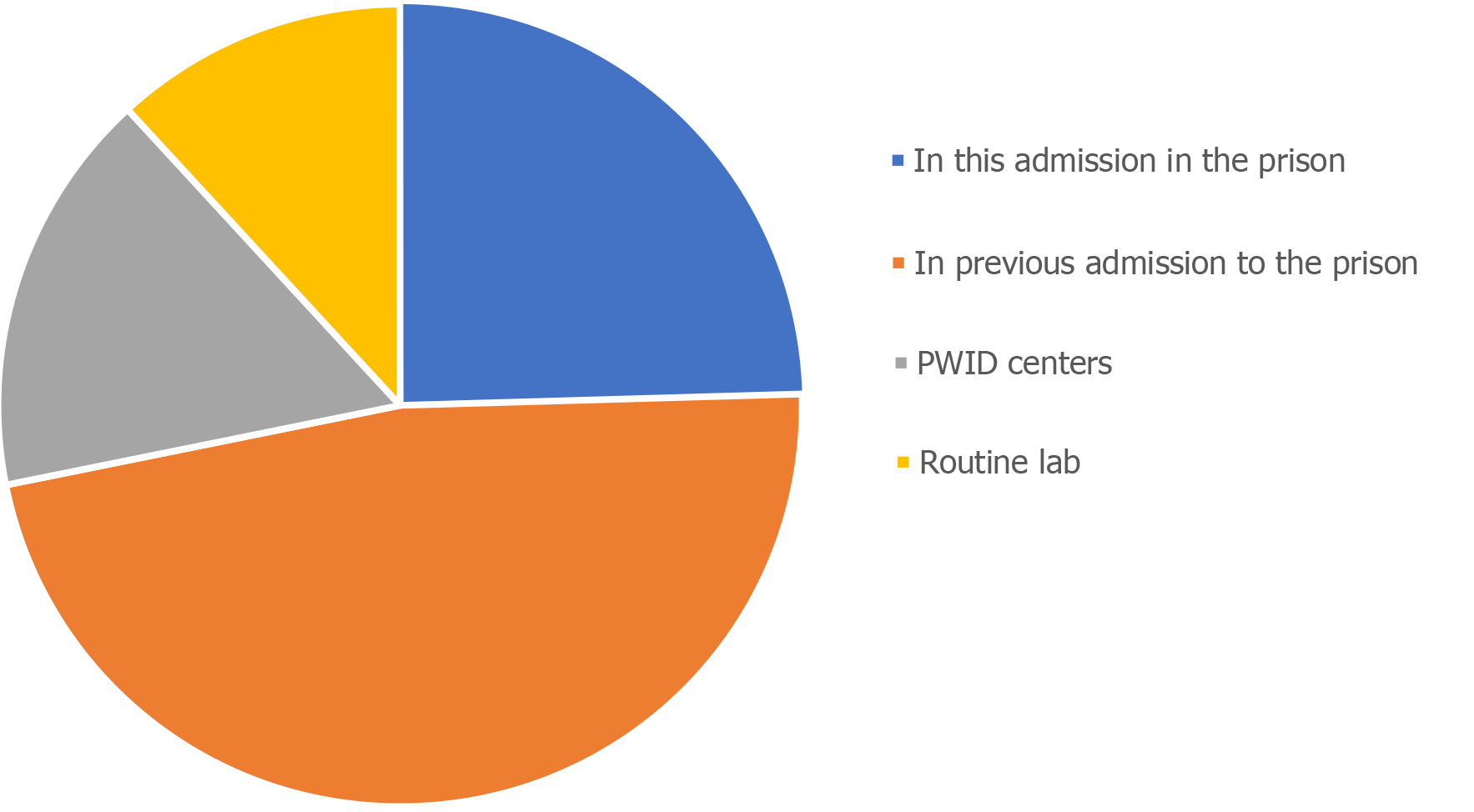

For most patients (68.3%), the diagnosis of HCV infection was made in prison, while for a minority, it was established in PWID (18.4%) or during routine laboratory data performed outside the prison (13.3%) (Figure 2).

Laboratory data are depicted in Table 2. Except for slight elevation of ALT and GGT, all laboratory data were within the normal range. There were no patients with positive HBs antigen but there were 41.8% with positive HBc antibody.

| Laboratory data | Median (IQR) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 15.7 (14.9-16.0) |

| Leukocytes, × 109/L | 7.9 (7.0-10.2) |

| Platelets, × 109/L | 204.5 (175.8-238.8) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 58.4 (55.0-61.1) |

| AST, U/L | 36.0 (28.0-47.8) |

| ALT, U/L | 47.0 (31.0-67.0) |

| GGT, U/L | 41.5 (27.0-72.0) |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 76.5 (65.5-94.5) |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.48 (0.32-0.6) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL | 162.0 (142.0-200.0) |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, ng/mL | 2.0 (1.4-3.5) |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.7-0.9) |

| INR | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) |

| Anti-HBc antibody+ | 41 (41.8%) |

| Anti-HBs antibody+ | 33 (33.7%) |

The median HCV viral load was 1865000 copies (range 673250-4580000). The most prevalent genotype was genotype 1a (54.1%), followed by genotype 3 (27.6%) genotype 4 (9.2%) and genotype 1b (6.1%) (Figure 3). All liver elastographies performed had more than 10 valid measurements and an interquartile range < 30%. According to the Fibroscan scoring card, 77.6% of the patients were classified as stage F0 to F2 and only 22.4% were classified as stage F3 or F4 (Table 3).

| Liver fibrosis according to liver elastography | n (%) |

| F0-F1 | 50 (51.0) |

| F2 | 26 (26.6) |

| F3 | 12 (12.2) |

| F4 | 10 (10.2) |

All patients completed 12 wk of treatment under daily staff distribution of medication, achieving 100% of adherence. Regarding treatment, regimens were prescribed: 45 patients (45.9%) got elbasvir/grazoprevir, 29 patients (29.6%) took sofosbuvir/ velpatasvir and 12 (12.2%) with sofosbuvir/Ledipasvir and 12 (12.2%) with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir, always without ribavirin. There were two patients that refused treatment, and eight patients started treatment in another institution after being moved. During the entire period of treatment, there were no reports of major adverse events and only seven patients complained of mild headache, without the need to take medication for relief.

SVR at week 12 after treatment was 99.0% (97/98). At this time, 52 (53.1%) patients gained weight and 86 (87.8%) referred improved quality of life. There were no cases of hepatitis B virus reactivation during the entire period of follow-up.

This is the first hepatitis C prison management program to be implemented in the country and settled the basis for an innovative national approach to deal with this problem.

This decentralized model of care involving onsite specialist consultation has overcome several of the traditional systemic barriers to provide efficient hepatitis C treatment to prisoners, namely hospital transfer, treatment interruption from transfer between correctional facilities, and low compliance due to non-assisted daily medication for several weeks. With the advent of DAAs, HCV infection treatment has achieved cure rates ranging from 90% to 100%. Therefore, with the aim of achieving HCV elimination in 2030, the focus is being turned into the high-risk groups, considered difficult-to-treat populations, traditionally due to their barriers in being engaged in health care.

The micro-elimination approach relates to target some subpopulations of HCV-infected people, namely high-risk populations, providing tailored services and the best interventions regarding the population’s needs in order to reach engagement and high rates of diagnosis and treatment.

One of the main focus of treatment and one of the cornerstones of the global micro-elimination strategy is also to reduce transmission by infected people, potentially contributing to treatment as prevention.

Although prisoners are undoubtedly considered a high-risk population and one of the main targets for micro-elimination, there is no universal policy for the provision of HCV testing/screening in this population. A recent European study showed that in 16 of 25 countries, HCV screening is not performed routinely but only if requested by the inmate[9]. In this study, where upon all inmates were tested for HCV regardless of the presence of risk factors, we found a prevalence of chronic HCV infection of 4.4%. Therefore, it seems justifiable that systematic screening of all prisoners upon admission to the correctional system should be pursued and recommended as an essential component of every national elimination strategy. In our program, as all the prisoners were always tested at admission in prison, we achieved very good results when compared with other studies[16-19].

In Portugal, there is unrestricted access to DAA therapy for chronic HCV infection since 2016. Although many patients had already been treated, vulnerable populations such as prisoners, only have access to therapy through general hospitals, with the need for specialist consultation implying frequent visits to hospital, a costly, time-consuming and distressing transport of prisoners. The prison setting could be, however, an ideal opportunity and an appropriate environment to provide hepatitis C treatment, breaking all the usual barriers in the access of treatment that this high-risk population have to face including reasons that lead to treatment interruption or diminished efficacy. In the community setting, these subjects would not normally receive treatment due to substance use related disorders (alcohol/drugs), psychiatric comorbidities, social stigma, lack of access to health care services and poor adherence to treatment. However, in the correctional system, these obstacles can be surpassed, as incarcerated people have limited access to alcohol and drugs and are actively treated for their mental illness, allowing a concentrated and targeted healthcare approach. A DDA-based program started in a correctional facility in Cairns, Australia, resulted in reduction of HCV prevalence from approximately 12% to less than 1% over a 22-mo period, showing that is not only feasible but also a very effective strategy[12].

As established in this project, hospital doctors moved to prison, allowing all HCV management to be done onsite, avoiding one major hurdle which is the frequent hospital visits these patients would otherwise need. This strategy of relocation of HCV specialists, together with daily staff distribution of medication and the advantages of DAA therapy mentioned above, resulted in a successful 100% of patients' adherence to the treatment plan. Consequently, SVR 12 rate was 99.0% in this difficult-to-treat population, showing that this strategy is not only feasible but also very effective.

Regarding risk factors to acquire HCV infection, in our study we found that 74.5% of the patients reported a lifetime history of injecting drugs use. Several studies showed higher odds ratio for HCV among prisoners who injected drugs[9,20]. Tattooing is also an important risk factor, especially if performed in non-licensed settings or in prison[21]. As drugs injection inside prison is not permitted, one major pathway for transmission of HCV infection is through previously infected material used for tattooing, as inmates perform tattoos with artisanal instruments that are not adequately sterilized. In our study, we found that 74.5% of the patients had tattoos, and 38.8% of whom had performed them inside prison. Interestingly, the majority of inmates did not recognize tattooing as a potential pathway for transmitting infection. Although until now, we have no cases of reinfection, in the Cairns study, six re-infected patients were reported. Thus, it is very important to elucidate the risks of using non-sterile devices to reduce the risk of transmission and reinfection, always bearing in mind that prisoners frequently cycle between incarceration and freedom, creating new networks for hepatitis C transmission. In our program, an important issue was also to prevent re-infection and "de novo" infection in the prison setting. Thus, our follow-up strategy was to re-screen all the patients every year (average length of stay in prison was 2 years) and implement educational measures through not only the medical team and the local nurses but also with educational sessions given by the medical team to all the prisoners, where all the risk factors and pathways to acquire HCV infection was explained.

Despite the excellent results reported here, HCV treatment in prison is demanding and there are still challenges to face, as shown from other successful experiences[17,18,21]. First, treatment of inmates requires careful attention and dedicated training to health care providers in order to create a good doctor–patient relationship, a keystone of care. Prison's nurses played also a major role, not only for therapeutic compliance but also highlighting the measures to prevent reinfection.

Second, to provide dedicated outpatient clinic in the prison setting, it is necessary total availability of the medical team, as it implies several visits to the prison as well as some logistic issues (e.g., availability of a portable Fibroscan equipment). Lastly, the average length of incarceration is very variable, and could only last some weeks. For some patients in whom therapy is initiated in prison, it needs to be completed in the community, making the interaction between the correctional system and the medical team in the community essential to avoid loss to follow-up.

There are also some improvements that can be done in our program. With total availability of pangenotypic drugs that were not available in the beginning of our program, determining genotype is not needed and could be a step forward treatment simplification. In addition, access to new technologies as TRODs GeneXpert and immediate availability of the drugs would reduce the number of outpatients clinics and the time from diagnose and beginning of the treatment.

A major breakthrough achieved with this project was the recognition of its success by the national health authorities who established a strategic plan of a national program in Prisons, aiming to detect and treat all the inmates with HCV infection, under the guidance of specialist doctors moving into prison sites (Diário da República n.º 4/2018, Série II de 2018-01-05, despacho 283/2018).

In conclusion, we showed a 4.4% prevalence of HCV infection in a prison setting after universal screening at admission. Although demanding, decentralizing a specialized medical team from the hospital to the prison as well as daily staff distribution of DAA medication, improved the prisoners access to hepatitis C treatment and lead to a very high rate of hepatitis C cure (99.0% rate of SVR 12 in our study).

Micro-elimination plans as the one we have developed should be promoted to benefit both the individual prisoners and the global efforts to the community to achieve hepatitis C elimination.

Hepatitis C is now a curable infectious disease with high rates of cure, reaching almost 100% cure with the use of direct antiviral agents.

The World Health Organization defined the aim of achieving hepatitis C virus (HCV) elimination by 2030. Although, to achieve this ambitious goal, we have to reach difficult to access groups, as persons who inject drugs and prisoners.

The aim of our program was to develop a research program of management and follow-up of a cohort of HCV monoinfected patients treated with direct-acting antiviral agents in the prison setting.

We developed a strategy where a medical team (2-3 doctors) from the hospital went to prison and was responsible for outpatient clinics, liver elastography, and give the medication on-site, increasing the access to care by avoiding any need to move the patients outside the prison.

Screening of 2451 inmates resulted in 276 prisoners (11.3%), of whom 108 prisoners mono-infected for HCV. Two patients refused to participate in the project and eight were transferred to other institution before starting the treatment. All patients completed 12 wk of treatment (100% adherence), achieving a sustained virological response (SVR) at week 12 after treatment of 99.0% (97/98).

In a particularly difficult to achieve population, we achieved a SVR at week 12 after treatment of 99.0%, with 100% adherence to treatment in patients that accepted the treatment.

These results show that an innovative and "in-loco" project in this special population could be the pathway to achieve HCV elimination in 2030. After this pilot project, a national program was created implementing our strategy. Therefore, currently in Portugal, every prisoner has access to treatment inside the prison.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Portugal

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Loustaud-Ratti V, Matsui K S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Denniston MM, Jiles RB, Drobeniuc J, Klevens RM, Ward JW, McQuillan GM, Holmberg SD. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003 to 2010. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160:293-300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 529] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 52.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wisløff T, White R, Dalgard O, Amundsen EJ, Meijerink H, Kløvstad H. Feasibility of reaching world health organization targets for hepatitis C and the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:1066-1077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Behzadifar M, Gorji HA, Rezapour A, Bragazzi NL. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among prisoners in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mohd Hanafiah K, Groeger J, Flaxman AD, Wiersma ST. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: new estimates of age-specific antibody to HCV seroprevalence. Hepatology. 2013;57:1333-1342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1770] [Cited by in RCA: 1846] [Article Influence: 153.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 5. | European Union HCV Collaborators. Hepatitis C virus prevalence and level of intervention required to achieve the WHO targets for elimination in the European Union by 2030: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:325-336. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 196] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 22.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aisyah DN, Shallcross L, Hayward A, Aldridge RW, Hemming S, Yates S, Ferenando G, Possas L, Garber E, Watson JM, Geretti AM, McHugh TD, Lipman M, Story A. Hepatitis C among vulnerable populations: A seroprevalence study of homeless, people who inject drugs and prisoners in London. J Viral Hepat. 2018;25:1260-1269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69:461-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1281] [Cited by in RCA: 1209] [Article Influence: 172.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Enggist S, Møller L, Galea G, Udesen C, Prisons and Health. WHO Regional Office for Europe 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/128603/Prisons%20and%20Health.pdf;sequence=1. |

| 9. | Bielen R, Stumo SR, Halford R, Werling K, Reic T, Stöver H, Robaeys G, Lazarus JV. Harm reduction and viral hepatitis C in European prisons: a cross-sectional survey of 25 countries. Harm Reduct J. 2018;15:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akiyama MJ, Kaba F, Rosner Z, Alper H, Kopolow A, Litwin AH, Venters H, MacDonald R. Correlates of Hepatitis C Virus Infection in the Targeted Testing Program of the New York City Jail System. Public Health Rep. 2017;132:41-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ranieri R, Starnini G, Carbonara S, Pontali E, Leo G, Romano A, Panese S, Monarca R, Prestileo T, Barbarini G, Babudieri S; SIMSPe Group. Management of HCV infection in the penitentiary setting in the direct-acting antivirals era: practical recommendations from an expert panel. Infection. 2017;45:131-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bartlett SR, Fox P, Cabatingan H, Jaros A, Gorton C, Lewis R, Priscott E, Dore GJ, Russell DB. Demonstration of Near-Elimination of Hepatitis C Virus Among a Prison Population: The Lotus Glen Correctional Centre Hepatitis C Treatment Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:460-463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1777] [Cited by in RCA: 1810] [Article Influence: 258.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 14. | Bedossa P, Poynard T. An algorithm for the grading of activity in chronic hepatitis C. The METAVIR Cooperative Study Group. Hepatology. 1996;24:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2860] [Cited by in RCA: 3078] [Article Influence: 106.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kim AY, Nagami EH, Birch CE, Bowen MJ, Lauer GM, McGovern BH. A simple strategy to identify acute hepatitis C virus infection among newly incarcerated injection drug users. Hepatology. 2013;57:944-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kronfli N, Dussault C, Klein MB, Lebouché B, Sebastiani G, Cox J. The hepatitis C virus cascade of care in a Quebec provincial prison: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2019;7:E674-E679. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Connoley D, Francis-Graham S, Storer M, Ekeke N, Smith C, Macdonald D, Rosenberg W. Detection, stratification and treatment of hepatitis C-positive prisoners in the United Kingdom prison estate: Development of a pathway of care to facilitate the elimination of hepatitis C in a London prison. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:987-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Harris AM, Chokoshvili O, Biddle J, Turashvili K, Japaridze M, Burjanadze I, Tsertsvadze T, Sharvadze L, Karchava M, Talakvadze A, Chakhnashvili K, Demurishvili T, Sabelashvili P, Foster M, Hagan L, Butsashvili M, Morgan J, Averhoff F. An evaluation of the hepatitis C testing, care and treatment program in the country of Georgia's corrections system, December 2013 - April 2015. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:466. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Godin A, Kronfli N, Cox J, Alary M, Maheu-Giroux M. The role of prison-based interventions for hepatitis C virus (HCV) micro-elimination among people who inject drugs in Montréal, Canada. Int J Drug Policy. 2020: 102738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Poulin C, Courtemanche Y, Serhir B, Alary M. Tattooing in prison: a risk factor for HCV infection among inmates in the Quebec's provincial correctional system. Ann Epidemiol. 2018;28:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Masarone M, Caruso R, Aglitti A, Izzo C, De Matteis G, Attianese MR, Pagano AM, Persico M. Hepatitis C virus infection in jail: Difficult-to-reach, not to-treat. Results of a point-of-care screening and treatment program. Dig Liver Dis. 2020;52:541-546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |