Published online Dec 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i12.1289

Peer-review started: August 2, 2020

First decision: September 30, 2020

Revised: October 12, 2020

Accepted: October 30, 2020

Article in press: October 30, 2020

Published online: December 27, 2020

Processing time: 137 Days and 14 Hours

Biliary dilation is frequently related to obstruction; however, non-obstructive factors such as age and previous cholecystectomy have also been reported. In the past two decades there has been a dramatic increase in opiate use/dependence and utilization of cross-sectional abdominal imaging, with increased detection of biliary dilation, particularly in patients who use opiates.

To evaluate associations between opiate use, age, cholecystectomy status, ethnicity, gender, and body mass index utilizing our institution’s integrated informatics platform.

One thousand six hundred and eighty-five patients (20% sample) presenting to our Emergency Department for all causes over a 5-year period (2011-2016) who had undergone cross-sectional abdominal imaging and had normal total bilirubin were included and analyzed.

Common bile duct (CBD) diameter was significantly higher in opiate users compared to non-opiate users (8.67 mm vs 7.24 mm, P < 0.001) and in patients with a history of cholecystectomy compared to those with an intact gallbladder (8.98 vs 6.72, P < 0.001). For patients with an intact gallbladder who did not use opiates (n = 432), increasing age did not predict CBD diameter (r2 = 0.159, P = 0.873). Height weakly predicted CBD diameter (r2 = 0.561, P = 0.018), but weight, body mass index, ethnicity and gender did not.

Opiate use and a history of cholecystectomy are associated with CBD dilation in the absence of an obstructive process. Age alone is not associated with increased CBD diameter. These findings suggest that factors such as opiate use and history of cholecystectomy may underlie the previously-reported association of advancing age with increased CBD diameter. Further prospective study is warranted.

Core Tip: What is current knowledge? Biliary dilation is often related to an obstructing process. Non-obstructive factors such as age and prior cholecystectomy have also been associated with biliary dilation. Rates of opiate use have dramatically increased within the United States over the past two decades. There has also been a dramatic increase in utilization of cross-sectional abdominal imaging over the past two decades What is new here. Opiate use is associated with biliary dilation in the absence of an obstructive process. Increasing opiate use and increasing utilization of imaging are resulting in increased incidental detection of biliary dilation leading to increased referrals for endoscopic workup. Contrary to conventionally held views, our study indicates that age alone is not associated with increased bile duct diameter. Increasing probability of opiate use and cholecystectomy with advancing age may underlie the previously-reported association of advancing age with increased bile duct diameter. Height is weakly associated with increased bile duct diameter, consistent with an organ scaling effect.

- Citation: Barakat MT, Banerjee S. Incidental biliary dilation in the era of the opiate epidemic: High prevalence of biliary dilation in opiate users evaluated in the Emergency Department. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(12): 1289-1298

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i12/1289.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i12.1289

Bile duct dilation is commonly related to an obstructive process such as a stone, stricture or a mass. However, biliary dilation has also been associated with non-obstructive factors such as advanced age and previous cholecystectomy[1]. The role of other patient factors such as height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and substance use in modulating biliary dilation have not been well defined.

The opioid epidemic sweeping across the United States, has resulted in a 3-fold increase in opiate prescriptions since 1999. Approximately 255.2 million opioid prescriptions were reported in 2012, corresponding to a staggering 81.3 prescriptions per 100 United States residents[2,3]. Despite the high prevalence of opiate use in the United States, the impact of opiates on bile duct diameter remains under-studied. Data are limited to only a few case series, some of which suggest that opiate use may be associated with dilatation of the bile duct in the absence of biliary obstruction[4,5]. However, small sample size, and lack of controls have limited the generalizability of these observations[4-6].

Additionally, perhaps in association with the ongoing national obesity epidemic, rates of cholecystectomy have increased over time, with over 900000 annual cholecystectomies currently performed in the United States[7]. Following cholecystectomy, it is widely accepted that the bile duct increases in diameter[1]. In 1894 Oddi postulated that the bile duct dilates following cholecystectomy so as to serve as a reservoir of bile—the pressure of which must then overcome the biliary sphincter pressure to enable bile to flow into the intestine[8]. Despite the longstanding recognition of this phenomenon, systematic evaluations of the impact of cholecystectomy on bile duct diameter have only emerged over the past 5 years[9]. The extent to which other patient factors may modulate the occurrence and the degree of biliary dilation following cholecystectomy remains to be determined.

Studies of the impact of aging on bile duct diameter in adults are similarly limited. In children, bile duct diameter increases with advancing age in relative proportion to a child’s growth curve[10]. In adults, some studies with limited sample sizes have suggested that common bile duct (CBD) diameter gradually increases with age in healthy adults[1,11,12]; however other studies have not demonstrated this trend[13].

In parallel with the progressively aging population, the ongoing opiate and obesity epidemics, and the rising rates of cholecystectomy, utilization of cross-sectional abdominal imaging has more than tripled over the past two decades[14,15]. An unintended consequence of this escalating utilization of cross sectional imaging is detection of incidental biliary dilation[14]. At our tertiary care academic endoscopy unit, over the last decade, we have noted a 5-fold increase in referrals for endoscopic evaluation of incidentally detected biliary dilation with normal bilirubin in opiate users. Although the majority of these patients were referred for Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), we opted to perform endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) for these patients, as this is a lower risk procedure. However EUS has not revealed pancreatic or biliary pathology in the vast majority of these patients.

Given the escalating endoscopic burden of this important problem, it would be informative to determine when biliary dilation is within the range of expected variation given the clinical context and characteristics of the patient, and when biliary dilation is more pronounced than would be expected, implying obstructive pathology which warrants further diagnostic evaluation. We therefore undertook a formal, controlled study on over 1500 patients to evaluate factors such as opiate use, age, cholecystectomy status, gender, ethnicity, height, weight and BMI which might predict increased bile duct diameter in patients with normal liver function tests and no visualized obstructive process on cross-sectional imaging.

We utilized an informatics platform, the Stanford Translational Research Integrated Database Environment (STRIDE) integrated standards-based platform[16]. This informatics resource consists of integrated components including a clinical data warehouse, which is based on the HL7 Reference Information Model, with clinical information on over 2 million pediatric and adult patients cared for at Stanford University Medical Center since 1995 and an application development framework for building research data management applications and initiating queries on the STRIDE platform[16].

Utilizing this STRIDE informatics platform and a retrospective cohort study design, we evaluated a 20% sample of patients over 18 years of age presenting to our Emergency Department (ED) for all causes over a 5-year period (2011-2016). We identified patients who had undergone computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of the abdomen with documentation of CBD diameter, and who had normal bilirubin with no evidence of biliary obstruction on imaging using our institutional informatics platform. Opiate use status is a mandatory question for all patients who are cared for in our ED. We extracted opiate use status responses from the electronic medical record (EMR) for all patients. Gallbladder status, age, gender, height, weight, BMI and ethnicity were also determined from the EMR.

Student’s t-test was performed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). Reported p-values are 2-sided, and comparisons attained statistical significance at P < 0.05. Linear regression analysis was conducted using standard techniques and categorical age analysis was performed by comparison of decades. This study was approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board (Protocol No. 41605).

This study included 1685 patients, 46% female and 54% male. There were 867 patients in the opiate user cohort and 818 in the non-opiate user cohort (mean age = 54.5 years vs 58.6 years, P = 0.20). Gender did not predict CBD diameter (P = 0.12). Stated ethnicity was only available for 56% of patients. For patients in whom ethnicity data were available, ethnicity did not predict CBD diameter (P = 0.09). Height and weight data were available for 86% of patients in this sample. Height weakly predicted CBD diameter (r2 = 0.561, P = 0.018), but weight and body mass index did not (r2 = 0.177, P = 0.29, r2 = 0.210, P = 0.21, respectively).

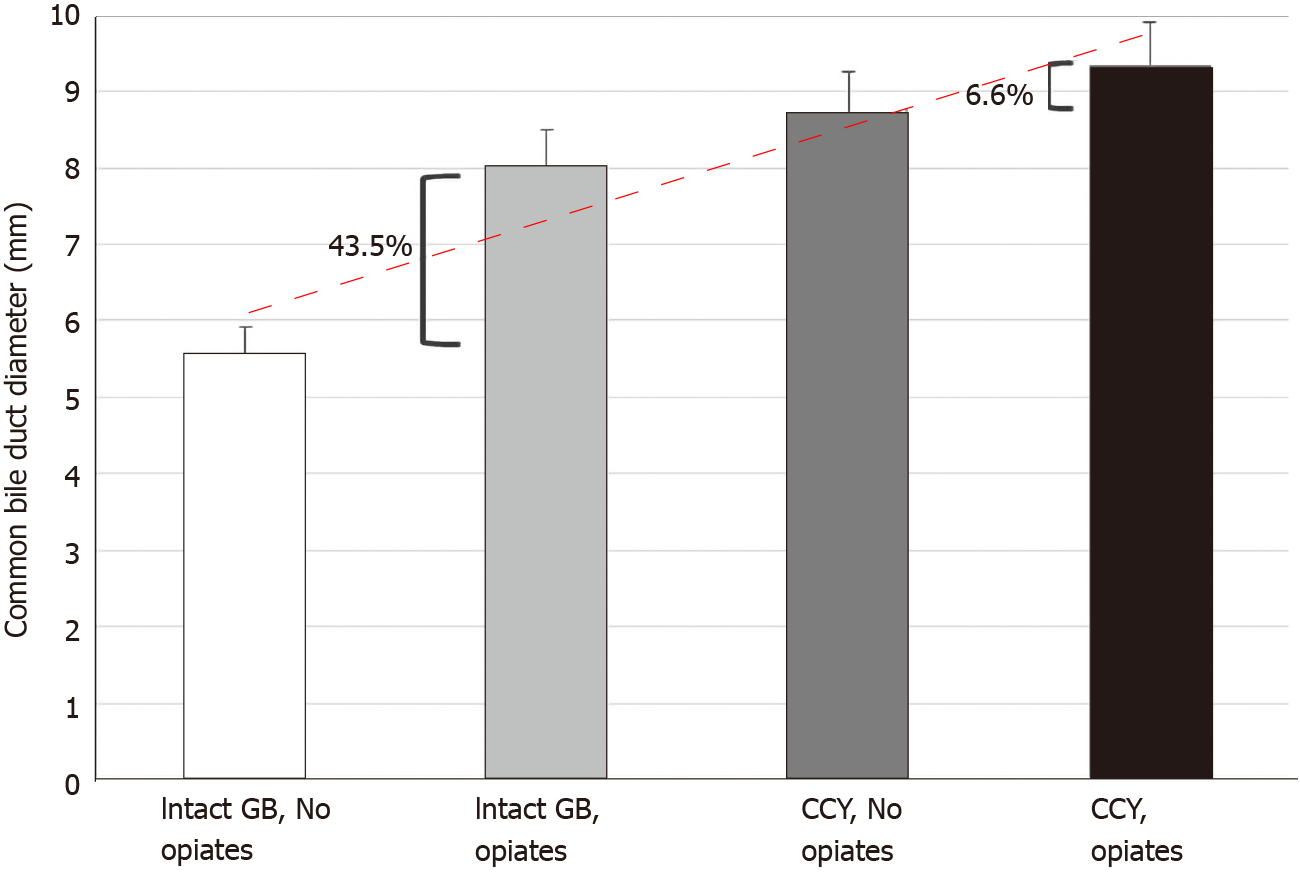

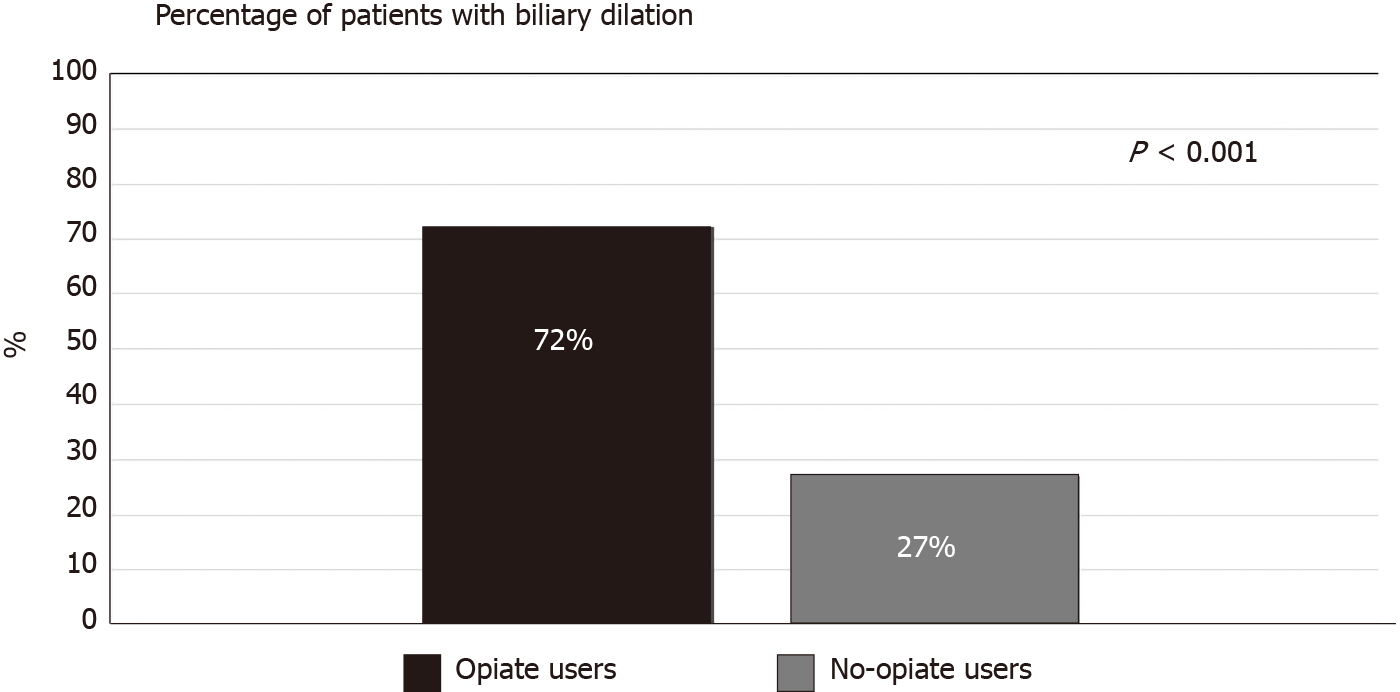

The mean CBD diameter was significantly higher in opiate users compared to non-opiate users (8.67 mm vs 7.24 mm, P < 0.001, Table 1). The mean CBD diameter was also significantly higher in patients with a history of cholecystectomy compared to those with an intact gallbladder (8.98 mm vs 6.72 mm, P < 0.001). The lowest CBD diameter was evident in patients with an intact gallbladder who did not use opiates, with sequentially increasing diameters noted in patients with an intact gallbladder who used opiates, and in those with prior cholecystectomy who did not use opiates, with the largest mean CBD diameter observed in patients with a history of both cholecystectomy and opiate use (Figure 1). Gallbladder status appeared to modulate the effect of opiates on bile duct diameter. Among patients with an intact gallbladder, opiate users had a CBD diameter that was 43.5% greater than non-opiate users. In contrast, among patients with a history of cholecystectomy, opiate users had a CBD diameter that was only 6.5% greater than non-opiate users (Table 1, Figure 1). When 7 mm was used as the threshold for normal bile duct diameter in all patients regardless of age and cholecystectomy status, 72% of opiate using patients had biliary dilation, as compared with only 27% of non-opiate using patients (Figure 2).

| Cholecystectomy status | Non opiate users, mean (SD) CBD diameter in mm | Opiate users, mean (SD) CBD diameter in mm | P value |

| All patients | 7.24 (2.28), n = 818 | 8.67 (1.89), n = 867 | P < 0.001 |

| Gallbladder intact (n = 814) | 5.58 (1.38), n = 432 | 8.01 (1.83), n = 382 | P < 0.001 |

| Gallbladder absent (n = 871) | 8.72 (1.86), n = 386 | 9.30 (1.72), n= 485 | P < 0.001 |

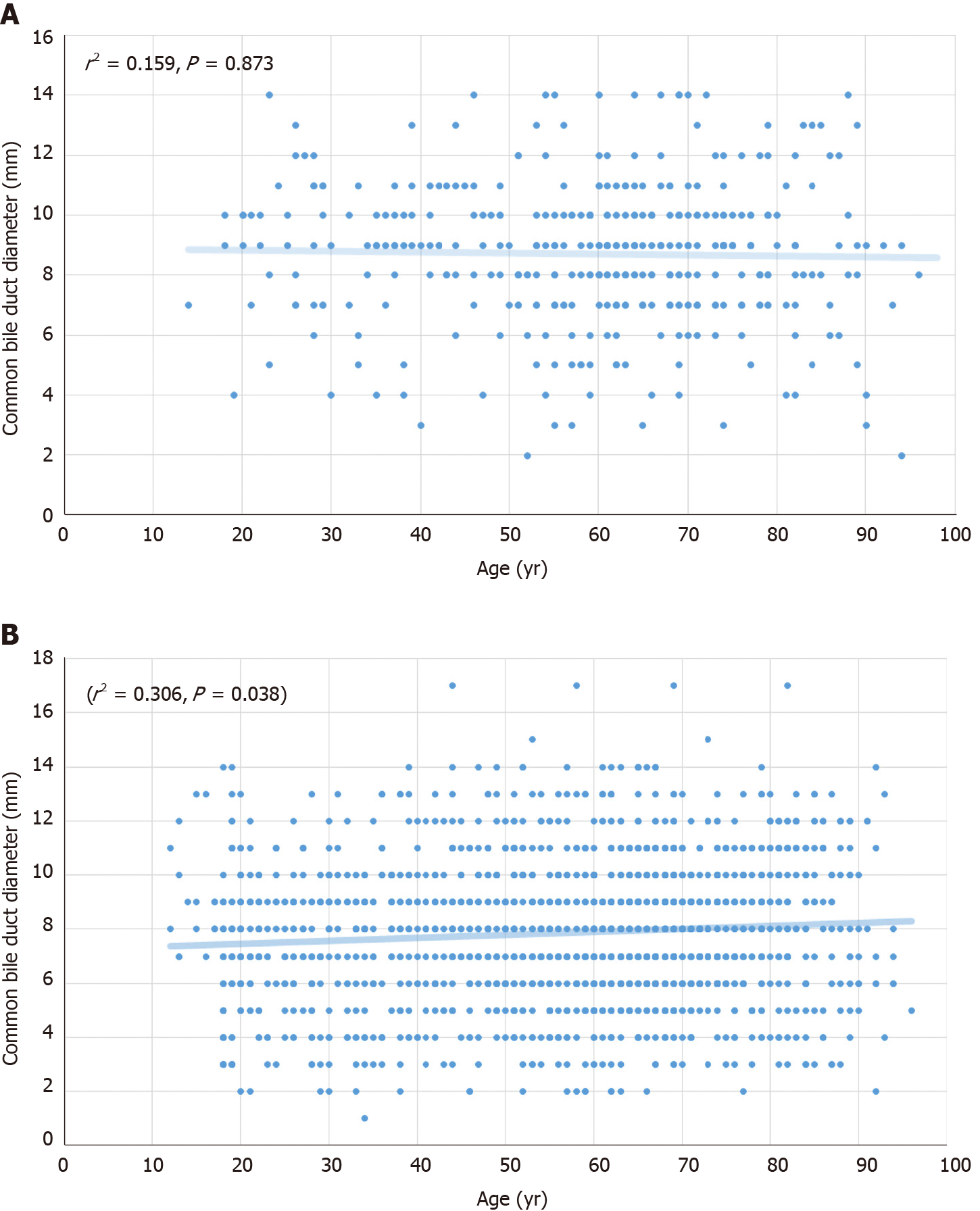

Importantly, increasing age did not significantly correlate with CBD diameter upon analysis as a continuous variable (r2 = 0.159, P = 0.873) or across age group categories (P = 0.217, Figure 3), for the population of patients with an intact gallbladder who did not use opiates (n = 432). Increasing age weakly predicted (r2 = 0.439, P = 0.027) increased CBD diameter in patients with a history of opiate use and/or a history of cholecystectomy (n = 1356). When all patient cohorts were grouped for analysis, including opiate users and non-users, and patients with and without a history of cholecystectomy (n = 1685), advancing age very weakly predicted (r2 = 0.306, P = 0.038) increased CBD diameter when analyzed as a continuous variable and across age group categories (Figure 3).

Prescription and illicit use of opiates has increased dramatically over the last 2 decades, with the emergence and escalation of a nationwide opiate epidemic[2,3]. The number of cholecystectomies performed annually in the United States has increased by more than 20%[7], and utilization of abdominal imaging has also increased approximately 3-fold over the same time period[14]. Age has previously been considered a factor associated with biliary dilation[1,11,13] and the proportion of the United States population aged over 65 has progressively increased and is projected to continue increasing. We therefore sought to evaluate the impact of each of these parameters on biliary dilation. It has been our impression that these concurrent phenomena have led to the increasing incidental detection of bile duct dilation in patients, which in turn is driving increased utilization of invasive, expensive and potentially risky endoscopic procedures. In our own practice we have noted a 5-fold increase in referrals for EUS and ERCP over the past decade, for patients with biliary dilation and a normal total bilirubin. Over 60% of these referrals in 2018 had concurrent opiate use. A few small previous case series have suggested that opiate use may be associated with biliary dilation; however, small sample size, study populations focused on opiate-dependent patients, confounding variables and lack of controls have limited the generalizability of these observations[4-6].

Our study, the largest conducted to date evaluating the association between opiate use and bile duct diameter, demonstrates that opiate use is a modulating factor associated with biliary dilation in the setting of a normal bilirubin. Patients who have both undergone cholecystectomy and use opiates have the largest CBD diameters overall. The impact of opiate use on CBD dilation is most striking in patients with an intact gallbladder. The opiate impact is muted in patients who have undergone cholecystectomy, perhaps related to a ceiling effect, given the significant pre-existing dilatory effect of cholecystectomy on the bile duct. We find that height is positively correlated with CBD diameter, consistent with an organ scaling effect. Our data indicate that patient weight, BMI, ethnicity and gender are not correlated with bile duct diameter.

Age has long been held to modulate bile duct diameter—this conventional wisdom is commonly asserted in radiology and gastroenterology textbooks. A standard radiology textbook, for example, indicates that an estimate of normal bile duct diameter at a given age may be roughly derived from considering a 4 mm bile duct diameter normal at age 40, and assuming a 1 mm increase in bile duct diameter for each subsequent decade of life[17]. The proposed association between age and CBD diameter was supported by a few limited studies conducted over 25 years ago, which concluded that CBD diameter is age-dependent[18-20]. However, a subsequent small prospective study did not demonstrate this association between age and bile duct diameter[13]. Our large study has not demonstrated an independent role for age in modulating CBD diameter in the absence of a history of cholecystectomy or opiate use. Our data suggest for the first time that other factors which modulate CBD diameter (cholecystectomy, opiate use) may account for the assertions in previous studies regarding increasing bile duct diameter with age. Further prospective study of this association is warranted.

Workup of incidentally detected biliary dilation in opiate users reflects yet another previously-unrecognized cost of the opiate epidemic. In recent years, cross-sectional imaging of the abdomen has supplanted abdominal radiography as the most frequently reimbursed abdominal imaging study[15]. Integrated health care systems and Medicare data demonstrate that for every 100 Medicare beneficiaries, over 50 CT scans, 50 abdominal ultrasounds and 15 abdominal MRIs are performed annually[21,22]. A subset of these patients undergo this imaging for evaluation of non-specific abdominal pain for which they may be prescribed opiates and may potentially then develop associated biliary dilation. Incidental findings from these imaging studies may then result in a cascade of healthcare expenses related to additional studies, diagnostic workup, procedures and ongoing surveillance, each with associated patient anxiety and the potential for adverse events[14].

In this era of escalating health care costs, our study indicates that the detection on imaging of incidental bile duct dilation without a visualized obstructing process in known opiate users with normal liver function tests may not require expensive and potentially risky endoscopic evaluation. However, the complexity of the problem of incidentally detected biliary dilation must also be acknowledged. The rising rates of Non Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease (NAFLD) and increased rates of statin utilization in the United States population result in associated liver function tests (LFT) abnormalities in up to 20% of NAFLD patients[23-25] and around 3% of statin users[26,27]. LFT abnormalities in these and in similar scenarios will impact the workup of patients referred for workup of incidental biliary dilation.

Additionally, valid concerns of referring and consulting physicians should be acknowledged. Sensitivity for detection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma, ranges from 76%-96% for CT[28-35] and from 83%-93.5% for MRI[30-35], with higher sensitivity corresponding with larger masses[31,33,35]. Additionally, in 5.4%-18.4% of patients with pancreatic malignancy, the lesion is isoattenuating relative to the background pancreas, with smaller lesions more likely to be isoattenuating[36-39]. Furthermore, cholangiocarcinoma, another concerning potential etiology of biliary obstruction and resultant dilation, often does not present as a mass on cross-sectional imaging and may be only partially occlusive, with incipient obstruction resulting in biliary dilation before significant LFT abnormalities develop[40-42]. Taken together, these limitations of cross sectional imaging, and the implicit potential for missed malignant lesions, prompt referring physicians to request additional evaluation for patients with incidental biliary dilation and biliary specialists to proceed with additional endoscopic evaluation.

Limitations of this study include its retrospective nature, reliance on data from the electronic medical record and reliance on reports from multiple radiologists for documentation of bile duct diameter. However, the large sample size should neutralize these effects. Due to limitations in opiate type, duration and use pattern details included within the electronic medical record, it was not possible to associate these parameters with CBD diameter. Prospective study of these phenomena would be informative to construct recommendations for when endoscopic evaluation of biliary dilation is most appropriate in the setting of these study limitations.

In conclusion, our data indicate that opiate use is associated with bile duct dilation in the absence of an obstructive process. We confirm that a history of prior cholecystectomy is associated with increased CBD diameter. We demonstrate that, in adult populations, height positively correlates with CBD diameter. Finally, we demonstrate that advancing age does not independently predict a larger CBD diameter in our analysis, and previously-reported associations of advancing age with larger CBD diameter may be attributable instead to other variables such as cholecystectomy and opiate use. Our data suggest that incidentally detected biliary dilation without a visualized obstructive process in the setting of normal bilirubin in known opiate users may not require expensive and potentially risky endoscopic evaluation.

Bile duct dilation is often related to an obstructive process such as a stone, stricture or a mass. The role of other patient factors such as height, weight, body mass index, and substance use in modulating biliary dilation have not been well defined.

In the past two decades, both opiate use/dependence and utilization of cross-sectional abdominal imaging have sharply increased. We have noted an increase in referrals to our academic tertiary care medical center for incidentally detected biliary dilation, particularly in patients who use opiates.

Our goal was to evaluation associations between opiate use, age, cholecystectomy status, ethnicity, gender, and body mass index to understand how these factors may be related to biliary dilation.

We evaluated associations between opiate use, age, cholecystectomy status, ethnicity, gender, and body mass index utilizing our institution’s integrated informatics platform. We evaluated 1685 Emergency Department patients (a 20% sample from 2011-2016) who had undergone cross-sectional abdominal imaging and had normal total bilirubin.

Diameter of the common bile duct was significantly higher in opiate users compared to non-opiate users (8.67 mm vs 7.24 mm, P < 0.001) and in patients with a history of cholecystectomy compared to those with an intact gallbladder (8.98 vs 6.72, P < 0.001). For patients with an intact gallbladder who did not use opiates (n = 432), increasing age did not predict common bile duct (CBD) diameter (r2 = 0.159, P = 0.873).

A history of cholecystectomy and opiate use are associated with common bile duct dilation in the absence of an obstructive process. Age alone does not appear to be associated with increased common bile duct diameter.

These findings suggest that factors such as opiate use and history of cholecystectomy may underlie the previously-reported association of advancing age with increased CBD diameter. Future prospective study would be desirable to expand upon these findings.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Boteon YL, Huang LY S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: A P-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Benjaminov F, Leichtman G, Naftali T, Half EE, Konikoff FM. Effects of age and cholecystectomy on common bile duct diameter as measured by endoscopic ultrasonography. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:303-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Data CDO. Centers for Disease Control U.S. Prescribing Rate Maps. 2016. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/maps/rxrate-maps.html. |

| 3. | Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, Losby J, Lewis B, Young R, Murphy LB, Dowell D. Vital Signs: Changes in Opioid Prescribing in the United States, 2006-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66:697-704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 716] [Cited by in RCA: 864] [Article Influence: 108.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Farahmand H, PourGholami M, Fathollah MS. Chronic extrahepatic bile duct dilatation: sonographic screening in the patients with opioid addiction. Korean J Radiol. 2007;8:212-215. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Smyth D, Stace N. Biliary dilatation induced by different opiate drugs: a case series of eight patients. N Z Med J. 2016;129:111-113. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Zylberberg H, Fontaine H, Corréas JM, Carnot F, Bréchot C, Pol S. Dilated bile duct in patients receiving narcotic substitution: an early report. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;31:159-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fingar KR SC, Weiss AJ, Steiner CA Most frequent operating room procedures performed in US Hospitals, 2003-2012. HCUP Statistical Brief #186. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. Available from: http://wwwhcup-usahrqgovlaneproxystanfordedu/reports/statbriefs/sb186-Operating-Room-Procedures-United-States-2012pdf 2014. |

| 8. | Oddi R. Sulla esistenza di speciali gangli nervosi in prossimit a dello sfintere del coledoco. Monitore Aoologico Italiano. 1894;5:216e7. |

| 9. | Landry D, Tang A, Murphy-Lavallée J, Lepanto L, Billiard JS, Olivié D, Sylvestre MP. Dilatation of the bile duct in patients after cholecystectomy: a retrospective study. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2014;65:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Feng A, O'hara SM, Gupta R, Fei L, Lin TK. Normograms for the Extrahepatic Bile Duct Diameter in Children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;64:e61-e64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Laks MP. Age and common bile duct diameter. Radiology. 2002;225:921-2; author reply 921. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Parulekar SG. Ultrasound evaluation of common bile duct size. Radiology. 1979;133:703-707. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Horrow MM, Horrow JC, Niakosari A, Kirby CL, Rosenberg HK. Is age associated with size of adult extrahepatic bile duct: sonographic study. Radiology. 2001;221:411-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | Smith-Bindman R. Use of Advanced Imaging Tests and the Not-So-Incidental Harms of Incidental Findings. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:227-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Moreno CC, Hemingway J, Johnson AC, Hughes DR, Mittal PK, Duszak R Jr. Changing Abdominal Imaging Utilization Patterns: Perspectives From Medicare Beneficiaries Over Two Decades. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:894-903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lowe HJ, Ferris TA, Hernandez PM, Weber SC. STRIDE--An integrated standards-based translational research informatics platform. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2009;2009:391-395. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Laing FC. The gallbladder and bile ducts. In: Rumack C, Wilson S, Carboneau JW, eds Diagnostic ultrasound. St Louis, Mo: Mosby, 1998: 207. |

| 18. | Wu CC, Ho YH, Chen CY. Effect of aging on common bile duct diameter: a real-time ultrasonographic study. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:473-478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kaude JV. The width of the common bile duct in relation to age and stone disease. An ultrasonographic study. Eur J Radiol. 1983;3:115-117. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Kaim A, Steinke K, Frank M, Enriquez R, Kirsch E, Bongartz G, Steinbrich W. Diameter of the common bile duct in the elderly patient: measurement by ultrasound. Eur Radiol. 1998;8:1413-1415. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Levin DC, Rao VM, Parker L, Frangos AJ, Sunshine JH. Bending the curve: the recent marked slowdown in growth of noninvasive diagnostic imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W25-W29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 89] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Smith-Bindman R, Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Lee C, Feigelson HS, Flynn M, Greenlee RT, Kruger RL, Hornbrook MC, Roblin D, Solberg LI, Vanneman N, Weinmann S, Williams AE. Use of diagnostic imaging studies and associated radiation exposure for patients enrolled in large integrated health care systems, 1996-2010. JAMA. 2012;307:2400-2409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 568] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sakurai M, Takamura T, Miura K, Kaneko S, Nakagawa H. Abnormal liver function tests and metabolic syndrome--is fatty liver related to risks for atherosclerosis beyond obesity? Intern Med. 2009;48:1573-1574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Corey KE, Kaplan LM. Obesity and liver disease: the epidemic of the twenty-first century. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:1-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Collantes R, Ong JP, Younossi ZM. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the epidemic of obesity. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71:657-664. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Athyros VG, Tziomalos K, Gossios TD, Griva T, Anagnostis P, Kargiotis K, Pagourelias ED, Theocharidou E, Karagiannis A, Mikhailidis DP; GREACE Study Collaborative Group. Safety and efficacy of long-term statin treatment for cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease and abnormal liver tests in the Greek Atorvastatin and Coronary Heart Disease Evaluation (GREACE) Study: a post-hoc analysis. Lancet. 2010;376:1916-1922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 506] [Cited by in RCA: 501] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Buchwald H, Williams SE, Matts JP, Boen JR. Lipid modulation and liver function tests. A report of the Program on the Surgical Control of the Hyperlipidemias (POSCH). J Cardiovasc Risk. 2002;9:83-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Bluemke DA, Cameron JL, Hruban RH, Pitt HA, Siegelman SS, Soyer P, Fishman EK. Potentially resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma: spiral CT assessment with surgical and pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1995;197:381-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 205] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bronstein YL, Loyer EM, Kaur H, Choi H, David C, DuBrow RA, Broemeling LD, Cleary KR, Charnsangavej C. Detection of small pancreatic tumors with multiphasic helical CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2004;182:619-623. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chen FM, Ni JM, Zhang ZY, Zhang L, Li B, Jiang CJ. Presurgical Evaluation of Pancreatic Cancer: A Comprehensive Imaging Comparison of CT Versus MRI. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2016;206:526-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Chu LC, Goggins MG, Fishman EK. Diagnosis and Detection of Pancreatic Cancer. Cancer J. 2017;23:333-342. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 29.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Fletcher JG, Wiersema MJ, Farrell MA, Fidler JL, Burgart LJ, Koyama T, Johnson CD, Stephens DH, Ward EM, Harmsen WS. Pancreatic malignancy: value of arterial, pancreatic, and hepatic phase imaging with multi-detector row CT. Radiology. 2003;229:81-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Ichikawa T, Haradome H, Hachiya J, Nitatori T, Ohtomo K, Kinoshita T, Araki T. Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: preoperative assessment with helical CT vs dynamic MR imaging. Radiology. 1997;202:655-662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 163] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sheridan MB, Ward J, Guthrie JA, Spencer JA, Craven CM, Wilson D, Guillou PJ, Robinson PJ. Dynamic contrast-enhanced MR imaging and dual-phase helical CT in the preoperative assessment of suspected pancreatic cancer: a comparative study with receiver operating characteristic analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:583-590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Tamm EP, Loyer EM, Faria SC, Evans DB, Wolff RA, Charnsangavej C. Retrospective analysis of dual-phase MDCT and follow-up EUS/EUS-FNA in the diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. Abdom Imaging. 2007;32:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ishigami K, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Tajima T, Asayama Y, Nishie A, Hirakawa M, Ushijima Y, Okamoto D, Nagata S, Nishihara Y, Yamaguchi K, Taketomi A, Honda H. Diagnostic value of the delayed phase image for iso-attenuating pancreatic carcinomas in the pancreatic parenchymal phase on multidetector computed tomography. Eur J Radiol. 2009;69:139-146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kim JH, Park SH, Yu ES, Kim MH, Kim J, Byun JH, Lee SS, Hwang HJ, Hwang JY, Lee SS, Lee MG. Visually isoattenuating pancreatic adenocarcinoma at dynamic-enhanced CT: frequency, clinical and pathologic characteristics, and diagnosis at imaging examinations. Radiology. 2010;257:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Prokesch RW, Chow LC, Beaulieu CF, Bammer R, Jeffrey RB Jr. Isoattenuating pancreatic adenocarcinoma at multi-detector row CT: secondary signs. Radiology. 2002;224:764-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yoon SH, Lee JM, Cho JY, Lee KB, Kim JE, Moon SK, Kim SJ, Baek JH, Kim SH, Kim SH, Lee JY, Han JK, Choi BI. Small (≤ 20 mm) pancreatic adenocarcinomas: analysis of enhancement patterns and secondary signs with multiphasic multidetector CT. Radiology. 2011;259:442-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 182] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Min JH, Jang KM, Cha DI, Kang TW, Kim SH, Choi SY, Min K. Differences in early imaging features and pattern of progression on CT between intrahepatic biliary metastasis of colorectal origin and intrahepatic non-mass-forming cholangiocarcinoma in patients with extrabiliary malignancy. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:1350-1360. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Olthof SC, Othman A, Clasen S, Schraml C, Nikolaou K, Bongers M. Imaging of Cholangiocarcinoma. Visc Med. 2016;32:402-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Promsorn J, Soontrapa W, Somsap K, Chamadol N, Limpawattana P, Harisinghani M. Evaluation of the diagnostic performance of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DWI) in differentiating between benign and metastatic lymph nodes in cases of cholangiocarcinoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2019;44:473-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |