Published online Oct 27, 2020. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v12.i10.807

Peer-review started: April 11, 2020

First decision: April 26, 2020

Revised: July 27, 2020

Accepted: October 5, 2020

Article in press: October 5, 2020

Published online: October 27, 2020

Processing time: 195 Days and 7.7 Hours

Sarcopenia, which is a loss of skeletal muscle mass, has been reported to increase post-transplant mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing the first liver transplant. Cross-sectional imaging modalities typically determine sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis by measuring core abdominal musculatures. However, there is limited evidence for sarcopenia related outcomes in patients undergoing liver re-transplantation (re-OLT).

To evaluate the risk of mortality in patients with pre-existing sarcopenia following liver re-OLT.

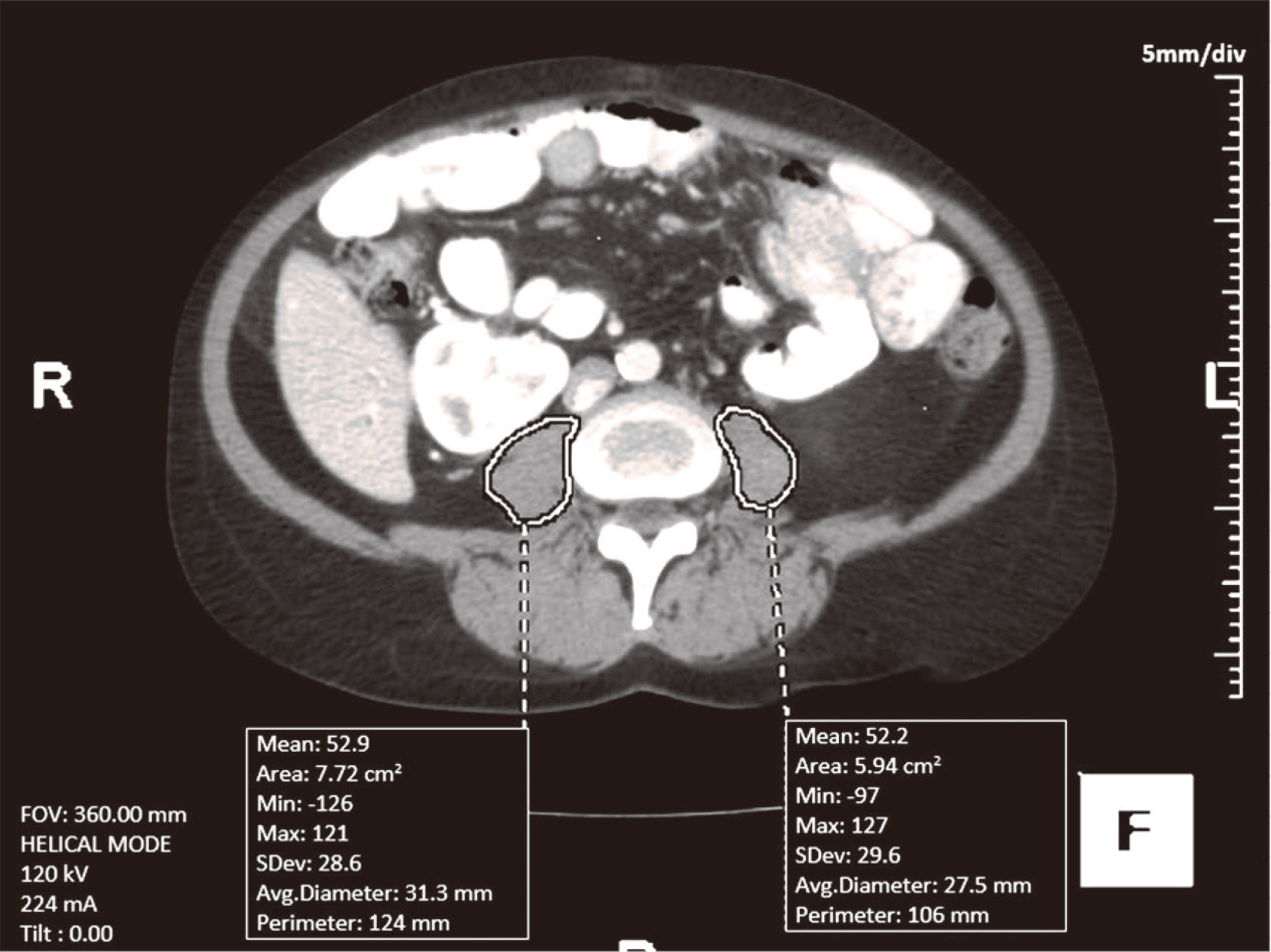

This is a retrospective study of all adult patients who had undergone a liver re-OLT at the University of Nebraska Medical Center from January 1, 2007 to January 1, 2017. We divided patients into sarcopenia and no sarcopenia groups. “TeraRecon AquariusNet 4.4.12.194” software was used to evaluate computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging of the patients done within one year prior to their re-OLT, to calculate the Psoas muscle area at L3-L4 intervertebral disc. We defined cutoffs for sarcopenia as < 1561 mm2 for males and < 1464 mm2 for females. The primary outcome was to compare 90 d, one, and 5-year survival rates. We also compared complications after re-OLT, length of stay, and re-admission within 30 d. Survival analysis was performed with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis. Continuous variables were evaluated with Wilcoxon rank-sum tests. Categorical variables were evaluated with Fisher’s exact tests.

Fifty-seven patients were included, 32 males: 25 females, median age 50 years. Two patients were excluded due to incomplete information. Overall, 47% (26) of patients who underwent re-OLT had sarcopenia. Females were found to have significantly more sarcopenia than males (73% vs 17%, P < 0.001). Median model for end stage liver disease at re-OLT was 28 in both sarcopenia and no sarcopenia groups. Patients in the no sarcopenia group had a trend of longer median time between the first and second transplant (36.5 mo vs 16.7 mo). Biological markers, outcome parameters, and survival at 90 d, 1 and 5 years, were similar between the two groups. Sarcopenia in re-OLT at our center was noted to be twice as common (47%) as historically reported in patients undergoing primary liver transplantation.

Overall survival and outcome parameters were no different in those with and without the evidence of sarcopenia after re-OLT.

Core Tip: There is a limited data on outcomes among patients with sarcopenia undergoing re-transplantation of the liver. A retrospective study of 57 patients who underwent re-transplantation showed 47% of patients had sarcopenia by Psoas muscle index at the level of L3-L4 Intervertebral disc prior to re-transplantation. Biological markers, outcome parameters, and survival at 90 d, 1 and 5 years, were similar between the two groups. Sarcopenia in re-transplantation was noted to be twice as common as historically reported in patients undergoing primary liver transplantation.

- Citation: Dhaliwal A, Larson D, Hiat M, Muinov LM, Harrison WL, Sayles H, Sempokuya T, Olivera MA, Rochling FA, McCashland TM. Impact of sarcopenia on mortality in patients undergoing liver re-transplantation. World J Hepatol 2020; 12(10): 807-815

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v12/i10/807.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v12.i10.807

The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in older people defined sarcopenia as the progressive and generalized loss of skeletal muscle mass and strength, resulting in an increased risk of poor quality of life and death[1]. Due to the alterations in protein turnover and metabolic changes in liver disease, sarcopenia is a common complication of cirrhosis[2]. In patients with cirrhosis, sarcopenia can be identified using cross-sectional imaging modalities such as computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to measure skeletal muscle area of core abdominal muscles[3]. Skeletal muscle measurements are obtained at the level of the third-fourth lumbar vertebrae as measurements at this level give an accurate estimation of total body skeletal muscle mass[4]. Psoas muscle area (PMA) is most commonly measured as it can be easily evaluated by imaging and is not susceptible to compression by ascites[5]. Sarcopenia is diagnosed when PMA is less than 1561 mm2 in men and less than 1464 mm2 in women with cirrhosis[3].

Sarcopenia has been noted in 22%-65% of cirrhotic patients and is associated with increased waiting list mortality in liver transplant patients, with studies reporting at least a 2-fold higher risk of mortality in sarcopenic patients compared to those without sarcopenia[3,4,6-8]. Sarcopenia is also associated with higher mortality after primary liver transplantation, with one-year survival rates following primary liver transplant ranging from 50%-64% for sarcopenic patients compared with 85%-94% for non-sarcopenic patients[3,9,10]. Graft survival is also affected by sarcopenia, and patients without sarcopenia experience significantly higher one-year graft survival rates than do patients with sarcopenia (90.1% and 77.9%, respectively)[11].

For liver transplant recipients with graft failure, re-transplantation (re-OLT) is the only effective treatment option[12]. The United Network for Organ Sharing reported that the graft failure rate for orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) recipients in the United States in 2016 was 7.3% and 9.8% at six months and one year, respectively[13]. Similarly, recent studies have found the incidence of re-OLT among OLT recipients to be 4%-17%[13-20]. While survival rates following primary liver transplantation continue to improve, overall survival following re-OLT remains 10% to 20% lower than after primary OLT[13,18].

Given the limited number of organs available for transplant, it is essential to determine factors that may be associated with increased mortality after liver re-transplantation. While sarcopenia has been associated with worse outcomes, and a higher risk of mortality following primary OLT, the effect of sarcopenia on re-OLT has not been addressed. Interestingly, studies have shown that sarcopenia can be reversible, with 28% of patients experiencing resolution of sarcopenia following primary OLT[21]. However, the incidence of sarcopenia prior to re-OLT is not well reported. This study was undertaken to examine the relationship between sarcopenia and re-OLT and to determine whether sarcopenia prior to re-OLT increases the risk of mortality following re-OLT.

This is a retrospective study of the patients who had liver re-OLT at University of Nebraska Medical Center (UNMC) between 01/01/07 and 01/01/2017. The study was approved by Institutional Review Board (IRB) of UNMC (IRB number# 236-17-EP). Two experienced staff body radiologists retrospectively evaluated abdominal CTs or MRIs of these patients, which were obtained within one year prior to their liver re-transplantation. “TeraRecon Aquarius Net 4.4.12.194” software (Foster City, CA, USA) was utilized to calculate the 2D PMA of each psoas muscle, measured in a semiautomatic fashion on a single axial image at L3-L4 intervertebral disc level. The sum of bilateral PMAs was recorded (Figure 1). Based on PMA, patients were divided into sarcopenia vs no sarcopenia group. Sarcopenia was defined as PMA < 1561 mm2 for males and PMA < 1464 mm2 for females[3].

Inclusion criteria were: (1) Age > 18 years old; and (2) Patients who had liver re-OLT between 01/01/07 - 01/01/2017 and had CT or MRI of the abdomen and pelvis done within one year prior to their liver re-OLT were included. Exclusion criteria were: (1) Patients who did not meet the inclusion criteria; (2) Pregnant females; and (3) Incomplete medical record information.

The primary outcome was to compare 90 d, one, and 5-year survival rates between the two groups (sarcopenia vs no sarcopenia). Secondary outcomes: Hospital length of stay (LOS), intensive care unit (ICU) LOS, readmission within 30 d, need for dialysis, pulmonary complications, primary non-function (PNF), acute rejection episodes, arterial and biliary complications between patients who had sarcopenia vs no sarcopenia. Pulmonary complications are conditions such as pneumonia, pleural effusions, or respiratory failure requiring supplement oxygen. PNF was defined as an irreversible graft failure requiring emergent liver retransplantation during the first 10 d of the transplantation. Acute rejection episodes were biopsy proven. Arterial complications were defined mainly as conditions such as hepatic artery thrombosis and stenosis. Biliary complications were defined as conditions such as biloma formation, cholangitis, anastomotic strictures and anastomotic leak. Potential confounding variables were also evaluated between those with and without sarcopenia including age, sex, body mass index, model for end stage liver disease (MELD), the time between the first and second transplants, and several biomarkers such as albumin, platelet counts, creatinine, International Normalized Ratio (INR), sodium, and presence of ascites. Comparison of baseline characteristics were done on sarcopenia and no sarcopenia groups to minimize selection bias. Survival analysis was conducted with Kaplan-Meier survival curve. Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to evaluate continuous variables, while Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 14 (The Stata Corp, College Station, TX, United States). The statistical methods of this study were reviewed by Harlan Sayles from Department of Biostatistics, College of Public Health, UNMC.

A total of 57 patients were included in our study; 32 (56%) were males and 25 (44%) were females. The overall median age in our study was 50 years. Two patients were excluded from the no sarcopenia group due to incomplete information. Overall, 47% (26) of patients underwent re-OLT had sarcopenia and 53% (29) of patients had no evidence of sarcopenia.

In our study, female gender was found to be significantly associated with sarcopenia with P < 0.001 (73% females vs 17% females in no sarcopenia group). Median MELD at re-OLT was 28 in both the groups. Patients in the no sarcopenia group had a trend of longer median time between the first and second transplant as compared to patients in the sarcopenia group, however this was not significant (36.5 mo vs 16.7 mo, P = 0.34). Biological markers including albumin, platelets, creatinine, INR and sodium were similar in both the groups (Table 1). There was no difference noted in regard to the presence of ascites in patients with sarcopenia vs no sarcopenia group (81% vs 62%, P = 0.13)

| Potential confounder | n | Sarcopenia [Median (IQR) or n (%)] | No sarcopenia [Median (IQR) or n (%)] | P value |

| Age (yr) | 55 | 49.5 (34, 59) | 50 (34, 59) | 0.906 |

| Male sex | 55 | 7 (27) | 25 (86) | < 0.001 |

| BMI | 55 | 24 (23, 29) | 24.7 (21.7, 30.9) | 0.781 |

| MELD1 | 55 | 28 (24, 33) | 28 (24, 33) | 0.846 |

| Time between 1st and 2nd OLT (mo) | 55 | 16.7 (5.2, 108.1) | 36.5 (7.4, 121.4) | 0.337 |

| Albumin | 55 | 2.6 (2.1, 3.3) | 2.7 (2.4, 3.1) | 0.685 |

| Platelets | 55 | 100 (75, 189) | 127 (79, 189) | 0.544 |

| Cr | 55 | 1.24 (0.87, 1.76) | 1.55 (1.26, 2.01) | 0.149 |

| INR | 55 | 1.3 (1.1, 2.1) | 1.5 (1.1, 1.8) | 0.892 |

| Na | 55 | 136 (132, 139) | 136 (134, 138) | 0.716 |

| Ascites | 55 | 21 (81) | 18 (62) | 0.127 |

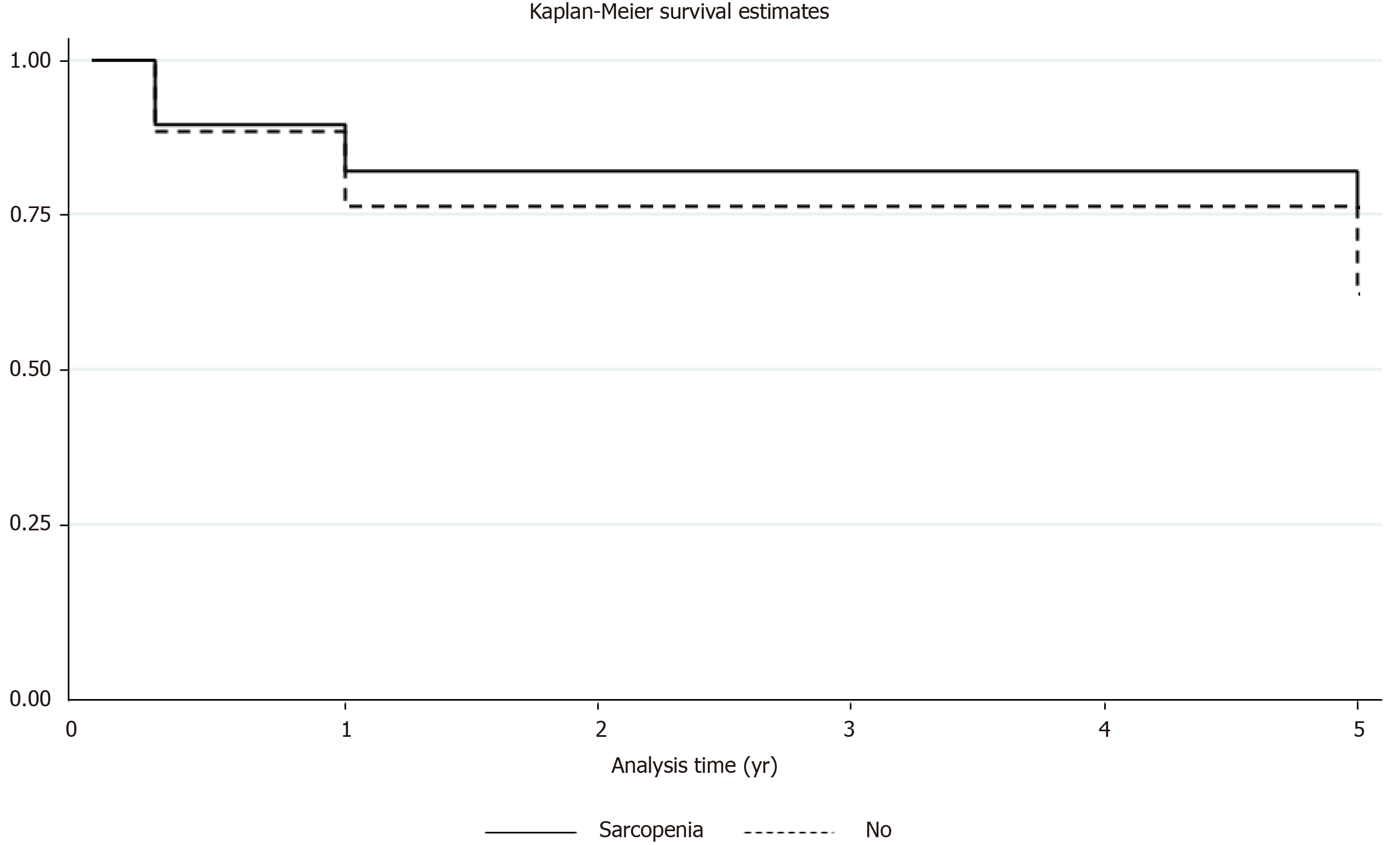

The survival rates between sarcopenia and no sarcopenia group at 90 d (88% vs 90%), 1-year (76% vs 81%) and 5-year (59% vs 68%) were similar. No statistical difference was noted in terms of mortality. Kaplan-Meier survival estimates were performed at 90 d, one, and 5-years between the two groups depicting no difference in the survival (Figure 2). The median ICU LOS, readmission to ICU, number of days intubated, need for dialysis and readmissions within 30 d were comparable between the two groups. The median total hospital LOS in no sarcopenia group was higher (21 d) as compared to sarcopenia group (14 d), but this was not statistically significant. The sarcopenia group had trend of higher pulmonary complications as compared to no sarcopenia group (38% vs 18%, P = 0.1). The post-transplant graft complications in terms of PNF, acute rejections, arterial and biliary complications were similar between the two groups (Table 2).

| Outcome | n | Sarcopenia Median (IQR) or n (%)] | No Sarcopenia Median (IQR) or n (%)] | P value |

| Post-op survival for 90 d | 55 | 23 (88) | 26 (90) | 1.000 |

| Post-op survival for 1 yr | 52 | 19 (76) | 22 (81) | 0.740 |

| Post-op survival for 5 yr | 41 | 13 (59) | 13 (68) | 0.746 |

| ICU length of stay (d) | 55 | 3 (2, 4) | 2 (2, 5) | 0.696 |

| Readmission to ICU | 54 | 4 (15) | 4 (14) | 1.000 |

| Total length of stay (d) | 55 | 13.5 (10, 27) | 21 (9, 28) | 0.661 |

| Intubation days | 55 | 1.5 (1, 3) | 1 (1, 3) | 0.484 |

| Pulmonary complications | 54 | 10 (38) | 5 (18) | 0.131 |

| Need for dialysis | 54 | 6 (23) | 7 (25) | 1.000 |

| Readmission within 30 d | 55 | 13 (50) | 13 (45) | 0.790 |

| PNF | 55 | 2 (8) | 0 (0) | 0.219 |

| Acute rejection | 55 | 2 (8) | 4 (14) | 0.672 |

| Arterial complications | 55 | 6 (23) | 5 (17) | 0.739 |

| Biliary complications | 55 | 8 (31) | 10 (34) | 1.000 |

Due to the high prevalence of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis and its association with adverse outcomes, it is important to identify patients with sarcopenia prior to liver transplantation. While multiple modalities have been used to diagnose sarcopenia, the current gold standard is to use CT and/or MRI imaging to estimate muscle mass[1]. These imaging modalities are preferred as they provide higher accuracy in quantifying muscle and fat as compared to other methods such as dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry or bio impedance analysis[5]. While earlier studies used the third lumbar skeletal muscle index (L3) to identify sarcopenia, recent studies have shown that PMA gives a more accurate estimation of total body skeletal muscle mass as it is not affected by ascites or hepatomegaly[3,5]. PMA has also been shown to be strongly associated with post-transplant mortality[9]. For these reasons, we used PMA obtained from CT and/or MRI images to diagnose sarcopenia in our study population.

Studies have shown that up to 17% of cirrhotic patients who undergo liver transplantation will require re-OLT due to graft failure. The most common indications for liver re-OLT reported in the literature include PNF, hepatic artery thrombosis, arterial and biliary complications, recurrence of disease and acute or chronic rejection. The median time interval from primary transplantation to re-OLT ranged from 8 d to 557 d in these studies[13,14,16-19]. Similar to previous studies, patients in our study underwent re-OLT for PNF, acute rejection, hepatic artery thrombosis, arterial and biliary complications. The incidence of these complications was similar in patients with sarcopenia compared to those without. Compared to previous studies, our study population without sarcopenia had longer median time from primary transplantation to re-OLT compared to sarcopenic patients (36.5 mo vs 16.7 mo). Although clinically, this was an important finding, but this difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.34). Unlike previous studies which have shown that sarcopenia is more prevalent in males, we found female gender to be significantly associated with sarcopenia in our study[7,21].

Sarcopenia has been well studied in patients undergoing primary liver transplantation but the effects of sarcopenia on patients who require re-OLT remain relatively unknown. Given that many of the clinical consequences of cirrhosis reverse with liver transplantation, it might be expected that sarcopenia also improves following transplantation. Montano et al[21] studied sarcopenia in cirrhotic patients undergoing liver transplantation and found that 28% of patients experienced resolution of sarcopenia following transplant. Other studies, however, found that the incidence of sarcopenia increased after transplant[5,8]. In a study by Tsien et al[8], 94% of patients with pre-transplant sarcopenia had persistent sarcopenia after transplant, and sarcopenia developed in 44% of patients who did not have sarcopenia prior to OLT. Likewise, Jeon et al[5] found the prevalence of sarcopenia after liver transplant to be 46%, an increase from 36% prior to transplant. Similarly, we found the incidence of sarcopenia at our center to be 47%, suggesting that sarcopenia persists after initial transplant. Potential mechanisms for this include ongoing muscle loss due to immunosuppression regimens as well as prolonged hospital courses and sedentary lifestyle following transplant[22].

The adverse effects of sarcopenia on cirrhotic patients undergoing liver transplantation are well documented in the literature. Patients with sarcopenia experience longer hospital stays as well as longer stays in the ICU[3,11,21]. They also have a higher frequency of bacterial infections and post-operative sepsis[11,21,23]. Infections which occur in sarcopenic patients are also more likely to be severe[24]. Interestingly, we found no difference in total hospital LOS or ICU LOS after re-OLT in patients with sarcopenia compared to those without sarcopenia. We did note higher rates of pulmonary complications in patients with sarcopenia, however this difference was not statistically significant. Most importantly, we found no significant difference in the overall survival at 90 d, one and 5-year between patients with and without evidence of sarcopenia. This finding was unexpected given that sarcopenia has been associated with both higher waiting list mortality and post-transplant mortality[4]. Tandon et al[7] reported that survival rates for patients on the waiting list were 16% higher at one year and 19% higher at three years for non-sarcopenic patients compared to those with sarcopenia. Furthermore, Englesbe et al[9] found that total psoas area significantly affected post liver transplant mortality and the risk of mortality increased as psoas area decreased. In that study, one-year survival after liver transplant was 49.7% for the sarcopenic group and 87% for the non-sarcopenic group.

As 4%-17% of liver transplant recipients will require liver re-OLT, understanding the impact of sarcopenia on these patients is becoming increasingly important[13-20]. However, few studies have examined sarcopenia in this population and the effects of sarcopenia on mortality remain unknown. While we did not find any significant difference in mortality between sarcopenic and non-sarcopenic patients, this may be explained by our small population size.

This is a single center retrospective study with small sample size of 55 patients (2 patients were excluded). The sarcopenia status of the patients prior to their first liver transplant was unknown.

Sarcopenia in re-OLT at our center was noted to be twice as common (47%) as historically reported in patients undergoing primary transplantation. Sarcopenia was more common in females. Our study population with sarcopenia had shorter median time from primary transplantation to re-OLT compared to the patients without sarcopenia. However, in re-OLT patient’s overall survival and other outcome parameters were no different in those with and without evidence of sarcopenia. Further, multicenter studies are needed to validate our findings.

Sarcopenia, which is a loss of skeletal muscle mass, has been reported to increase post-transplant mortality and morbidity in patients undergoing the first liver transplant. Cross-sectional imaging modalities typically determine sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis by measuring core abdominal musculatures.

Identification of sarcopenia is becoming more prevalent in the initial liver transplantation. However, there is limited evidence for sarcopenia related outcomes in patients undergoing liver re-transplantation (re-OLT).

The study aimed to evaluate the risk of mortality in patients with pre-existing sarcopenia following liver re-OLT.

This is a retrospective study of patients who had undergone a liver re-OLT. The presence of sarcopenia was determined by the Psoas Muscle Area on cross-sectional imaging. The primary outcome was to compare 90 d, one, and 5-year survival rates between sarcopenia and no sarcopenia group.

Overall, 47% of patients who underwent re-OLT had sarcopenia. Biological markers, outcome parameters, and survival at 90 d, 1 and 5 years, were similar between the two groups. Sarcopenia in re-OLT at our center was noted to be twice as common as historically reported in patients undergoing primary liver transplantation.

Overall survival and outcome parameters were no different in those with and without the evidence of sarcopenia after re-OLT.

Although sarcopenia has been shown to predict the outcomes after the first liver transplantation, our study did not show the difference in survival and outcome parameters between sarcopenia and non-sarcopenia groups. Besides, sarcopenia was more prevalent in patients undergoing re-OLT compared to initial transplantation. Larger prospective studies are needed to assess the impact of sarcopenia in patients undergoing re-OLT.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Soldera J S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang LL

| 1. | Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Baeyens JP, Bauer JM, Boirie Y, Cederholm T, Landi F, Martin FC, Michel JP, Rolland Y, Schneider SM, Topinková E, Vandewoude M, Zamboni M; European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Sarcopenia: European consensus on definition and diagnosis: Report of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People. Age Ageing. 2010;39:412-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6987] [Cited by in RCA: 8446] [Article Influence: 563.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Dasarathy S, Merli M. Sarcopenia from mechanism to diagnosis and treatment in liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1232-1244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 431] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Golse N, Bucur PO, Ciacio O, Pittau G, Sa Cunha A, Adam R, Castaing D, Antonini T, Coilly A, Samuel D, Cherqui D, Vibert E. A new definition of sarcopenia in patients with cirrhosis undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:143-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | van Vugt JLA, Alferink LJM, Buettner S, Gaspersz MP, Bot D, Darwish Murad S, Feshtali S, van Ooijen PMA, Polak WG, Porte RJ, van Hoek B, van den Berg AP, Metselaar HJ, IJzermans JNM. A model including sarcopenia surpasses the MELD score in predicting waiting list mortality in cirrhotic liver transplant candidates: A competing risk analysis in a national cohort. J Hepatol. 2018;68:707-714. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 158] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Jeon JY, Wang HJ, Ock SY, Xu W, Lee JD, Lee JH, Kim HJ, Kim DJ, Lee KW, Han SJ. Newly Developed Sarcopenia as a Prognostic Factor for Survival in Patients who Underwent Liver Transplantation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Montano-Loza AJ, Meza-Junco J, Prado CM, Lieffers JR, Baracos VE, Bain VG, Sawyer MB. Muscle wasting is associated with mortality in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:166-173, 173.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 537] [Cited by in RCA: 608] [Article Influence: 46.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tandon P, Ney M, Irwin I, Ma MM, Gramlich L, Bain VG, Esfandiari N, Baracos V, Montano-Loza AJ, Myers RP. Severe muscle depletion in patients on the liver transplant wait list: its prevalence and independent prognostic value. Liver Transpl. 2012;18:1209-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 383] [Cited by in RCA: 435] [Article Influence: 33.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tsien C, Garber A, Narayanan A, Shah SN, Barnes D, Eghtesad B, Fung J, McCullough AJ, Dasarathy S. Post-liver transplantation sarcopenia in cirrhosis: a prospective evaluation. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;29:1250-1257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Englesbe MJ, Patel SP, He K, Lynch RJ, Schaubel DE, Harbaugh C, Holcombe SA, Wang SC, Segev DL, Sonnenday CJ. Sarcopenia and mortality after liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211:271-278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 650] [Cited by in RCA: 623] [Article Influence: 41.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hamaguchi Y, Kaido T, Okumura S, Fujimoto Y, Ogawa K, Mori A, Hammad A, Tamai Y, Inagaki N, Uemoto S. Impact of quality as well as quantity of skeletal muscle on outcomes after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1413-1419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Harimoto N, Yoshizumi T, Izumi T, Motomura T, Harada N, Itoh S, Ikegami T, Uchiyama H, Soejima Y, Nishie A, Kamishima T, Kusaba R, Shirabe K, Maehara Y. Clinical Outcomes of Living Liver Transplantation According to the Presence of Sarcopenia as Defined by Skeletal Muscle Mass, Hand Grip, and Gait Speed. Transplant Proc. 2017;49:2144-2152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zarrinpar A, Hong JC. What is the prognosis after retransplantation of the liver? Adv Surg. 2012;46:87-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Schladt DP, Edwards EB, Harper AM, Wainright JL, Snyder JJ, Israni AK, Kasiske BL. Liver. Am J Transplant. 2016;16 Suppl 2:69-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Adani GL, Baccarani U, Risaliti A, Sainz-Barriga M, Lorenzin D, Costa G, Toniutto P, Soardo G, Montanaro D, Viale P, Della Rocca G, Bresadola F. A single-center experience of late retransplantation of the liver. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:2599-2600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chen GH, Fu BS, Cai CJ, Lu MQ, Yang Y, Yi SH, Xu C, Li H, Wang GS, Zhang T. A single-center experience of retransplantation for liver transplant recipients with a failing graft. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1485-1487. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Facciuto M, Heidt D, Guarrera J, Bodian CA, Miller CM, Emre S, Guy SR, Fishbein TM, Schwartz ME, Sheiner PA. Retransplantation for late liver graft failure: predictors of mortality. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:174-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim WR, Wiesner RH, Poterucha JJ, Therneau TM, Malinchoc M, Benson JT, Crippin JS, Klintmalm GB, Rakela J, Starzl TE, Krom RA, Evans RW, Dickson ER. Hepatic retransplantation in cholestatic liver disease: impact of the interval to retransplantation on survival and resource utilization. Hepatology. 1999;30:395-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lang H, Sotiropoulos GC, Beckebaum S, Fouzas I, Molmenti EP, Omar OS, Sgourakis G, Radtke A, Nadalin S, Saner FH, Malagó M, Gerken G, Paul A, Broelsch CE. Incidence of liver retransplantation and its effect on patient survival. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:3201-3203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Marudanayagam R, Shanmugam V, Sandhu B, Gunson BK, Mirza DF, Mayer D, Buckels J, Bramhall SR. Liver retransplantation in adults: a single-centre, 25-year experience. HPB (Oxford). 2010;12:217-224. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Pfitzmann R, Benscheidt B, Langrehr JM, Schumacher G, Neuhaus R, Neuhaus P. Trends and experiences in liver retransplantation over 15 years. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:248-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Montano-Loza AJ. Severe muscle depletion predicts postoperative length of stay but is not associated with survival after liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:1424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kallwitz ER. Sarcopenia and liver transplant: The relevance of too little muscle mass. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:10982-10993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 23. | Kalafateli M, Mantzoukis K, Choi Yau Y, Mohammad AO, Arora S, Rodrigues S, de Vos M, Papadimitriou K, Thorburn D, O'Beirne J, Patch D, Pinzani M, Morgan MY, Agarwal B, Yu D, Burroughs AK, Tsochatzis EA. Malnutrition and sarcopenia predict post-liver transplantation outcomes independently of the Model for End-stage Liver Disease score. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2017;8:113-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 188] [Cited by in RCA: 232] [Article Influence: 29.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Krell RW, Kaul DR, Martin AR, Englesbe MJ, Sonnenday CJ, Cai S, Malani PN. Association between sarcopenia and the risk of serious infection among adults undergoing liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:1396-1402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 200] [Article Influence: 16.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |