Published online Aug 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i8.646

Peer-review started: January 29, 2019

First decision: March 3, 2019

Revised: June 12, 2019

Accepted: July 4, 2019

Article in press: July 5, 2019

Published online: August 27, 2019

Processing time: 207 Days and 9.8 Hours

Intervention to improve outcomes in cirrhotic patients (CP) after hospital discharge often focus on 30 d readmission rate (RR). However, recent studies suggest dissociation between RR and survival. At our center, CP are now offered outpatient telephonic transitional care (OTTC) by a care coordinator for 30 d after hospital discharge.

To determine the effect of OTTC on survival in CP.

In this cohort study from a tertiary center, CP who received OTTC formed the intervention group. They were compared with a control group discharged during the same period. Mortality and RR were compared between the groups.

After OTTC introduction, 194 CP were discharged. After applying exclusion criteria, 169 CP (51% male, mean age 58 years ± 12 years) were included. OTTC group comprised 76 patients and was compared with 93 controls. Baseline disease and index admission related characteristics were not significantly different between the groups. The intervention group showed significantly higher 6 mo survival compared to controls (84.2% vs 68.8%; P = 0.03), while RR at 1, 3, and 6 mo were comparable. On multivariable analysis, the intervention group showed lower odds for mortality compared to the controls (hazard ratio: 0.4; 95% confidence interval: 0.2-0.82; P = 0.012), while higher model for end-stage liver disease scores were associated with higher mortality (hazard ratio: 1.05; 95% confidence interval: 1.01-1.1; P = 0.024).

CP provided OTTC had higher 6 mo survival compared to controls without a difference in RR. Use of RR to gauge quality of care provided during hospitalization or subsequent transitional care programs should be revisited.

Core tip: We share results of a novel intervention that provides transitional care via telephone to cirrhotic patients after hospital discharge. Over a 6 mo follow-up, the intervention group experienced 60% lower odds for mortality compared to controls with similar readmission rates. Our manuscript not only describes an effective transitional care program to improve post-discharge outcomes in cirrhotic patients but also highlights the need to acknowledge the dissociation between readmissions and survival in this population.

- Citation: Rao BB, Sobotka A, Lopez R, Romero-Marrero C, Carey W. Outpatient telephonic transitional care after hospital discharge improves survival in cirrhotic patients. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(8): 646-655

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i8/646.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i8.646

Cirrhosis leads to over 150000 hospitalizations at an annual cost of nearly $4 billion in the United States[1,2]. There is growing awareness and concern regarding the high rates of readmission, which constitutes a significant medical, psychosocial, and financial burden[3-5]. A large prospective study involving 14 tertiary-care hepatology centers in the United States and Canada noted that 53% of cirrhotic patients (CP) experience at least one readmission within 3 mo of hospital discharge (HD)[6]. Readmission rate (RR) has been proposed as a national quality indicator and a factor that could gauge organizational performance and determine rates of reimbursement[3]. However, limiting readmissions in patients with advanced disease and complex medical conditions is challenging and not always in their best interest. Indeed, some have suggested that a reduction in readmissions may prejudice survival[7,8].

A few have tested the utility of adopting specialized interventions for reducing RR in CP. These include use of electronic checklists for discharge[9], intensive monitoring by a nurse practitioners after discharge[8], providing early outpatient follow-up[7], or creation of a dedicated outpatient hepatology caregiver team along with setting up of an outpatient paracentesis clinic[10]. While all the studies noted an improvement in adherence to medications and follow-up clinic visits with the interventions, the rate of readmissions remained unchanged[8] or even increased[7] despite a reduction in mortality. These findings reflect both efficacy of the intervention and dissociation between RR and survival.

At our center, outpatient telephonic transitional care (OTTC) was introduced with the goal of improving post hospitalization outcomes in CP. The primary objective of this study was to determine the effect of OTTC on survival at 1, 3, and 6 mo after HD in CP. The secondary objective was to determine the effect of OTTC on RR at 1, 3, and 6 mo after HD and explore the relationship of RR to survival.

At our tertiary care center, the OTTC program was introduced on March 1, 2016. It is delivered by a dedicated nurse care coordinator. The program is offered to CP for a period of 30 d after HD, provided the patients are not being discharged to hospice care. The OTTC program involves telephone based follow-up, active monitoring of diagnostic tests, coordination of outpatient care, and disease and medication related counseling. In the pilot phase of this program due to limited manpower, the OTTC program was only offered to CP who were deemed at high risk for readmission. This determination was made by the multi-disciplinary inpatient hepatology team prior to discharge. A registry of all the patients who received OTTC care was maintained. Standard of care treatment was continued for all study patients during their inpatient and transitional care period and the OTTC program was offered as an additional intervention to selected patients.

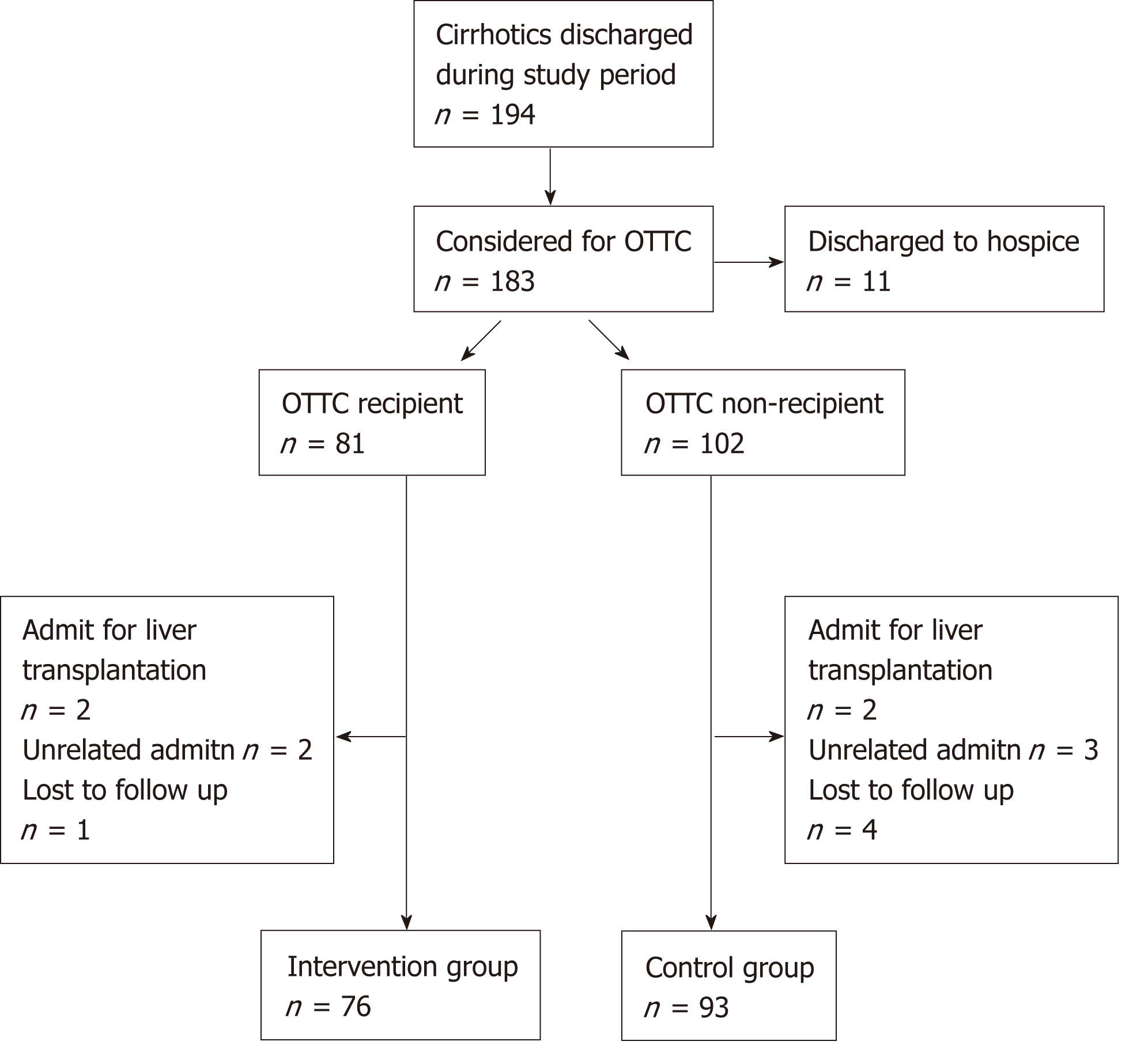

Hospital administrative data was surveyed to obtain a list of all the CP discharged from the inpatient hepatology service on our main campus facility between March 1 and December 31, 2016. All patients discharged within 2 mo since OTTC initiation were excluded from analysis because the tenets of the program were being actively modified and improved during this preliminary period, after which all the protocols were finalized. All patients were followed up for a 6 mo period after index hospitalization. Patients who had readmissions to the hospital for liver transplantation or readmission for reasons unrelated to underlying liver disease during the follow-up were excluded. Patients who were lost to all healthcare contact with any of our facilities in the follow-up period were excluded because no determination of their readmission or survival status could be reliably made. Among all the CP, those who received OTTC formed the intervention group and those who were discharged during the same period without the OTTC intervention formed the control group.

Chart review was done to obtain demographic data (gender, sex, insurance coverage), details regarding liver disease [etiology, related complications, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score], medications, laboratory, imaging, and endoscopic data for all study patients. Characteristics of index and subsequent hospitalizations including reason for admission, medical problems addressed during hospitalization, length of stay, and destination at discharge were recorded. While the OTTC program was provided to only the CP being discharged from our main campus, readmissions were tracked both to our main campus and satellite facilities. Details regarding scheduling, timing, and adherence to post discharge follow-up appointments in the hepatology clinic and at the paracentesis procedure unit were obtained.

Rates of actuarial survival at 1, 3, and 6 mo after index HD was compared between the intervention and control group. In addition, unplanned RR at 1, 3, and 6 mo after index hospitalization were also compared between the groups.

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (25th, 75th percentiles), or frequency (percent). A univariable analysis was performed to assess differences between the two groups. Non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare continuous or ordinal variables, and Pearson’s chi-square tests were used for categorical factors. Follow-up time was defined as months since initial discharge to the first of readmission or death, and subjects were censored at 6 mo if still alive without readmission. Readmission and death were treated as competing events and cumulative incidence of readmission was estimated using the Fine and Gray competing risks model. In addition, multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to assess factors associated with mortality. An automated stepwise variable selection was used to choose the final models. Survival analysis was done to assess differences in overall survival between the groups. All analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4, The SAS Institute, Cary, NC, United States), and a P < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Between May 1 and December 31, 2016, 194 CP were discharged from the inpatient hepatology service. A total of 169 CP (51% male, mean age 58 ± 12 years) formed the study cohort with the intervention and control groups having 76 (45%) and 93 (55%) patients, respectively. Flowchart describing study cohort selection is depicted in Figure 1.

Common etiologies for cirrhosis in the cohort were alcoholic (32.5%) and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (23.7%) with average MELD score during index hospitalization being 18. Medical complications including hepatic encephalopathy, infections, acute kidney injury, and gastrointestinal bleeding were each addressed in approximately a third of the cohort during index hospitalization, which spanned a median 5 d. The intervention and control groups showed no significant difference with regards to baseline disease or index hospitalization related characteristics (Table 1).

| Factor | Total, n = 169 | Intervention, n = 76 | Control, n = 93 | P value |

| Male | 86 (50.9) | 41 (53.9) | 45 (48.4) | 0.54 |

| Age | 58.2 ± 12.0 | 58.6 ± 11.4 | 57.9 ± 12.6 | 0.75 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||||

| Alcohol | 55 (32.5) | 27 (35.5) | 28 (30.1) | |

| NAFLD | 40 (23.7) | 18 (23.7) | 22 (23.7) | |

| HCV | 27 (16.0) | 11 (14.5) | 16 (17.2) | |

| HBV | 2 (1.2) | 0 | 2 (2.2) | 0.49 |

| Combination of above | 5 (3.0) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (4.3) | |

| Others | 40 (24.9) | 19 (25.0) | 21 (22.6) | |

| MELD score during index admission | 17.7 ± 7.9 | 17.8 ± 8.6 | 17.5 ± 7.3 | 0.88 |

| Problems during initial hospitalization | ||||

| HE | 64 (37.9) | 34 (44.7) | 30 (32.3) | 0.11 |

| Infection | 51 (30.2) | 23 (30.3) | 28 (30.1) | 1 |

| AKI | 64 (37.9) | 30 (39.5) | 34 (36.6) | 0.75 |

| GIB | 57 (33.7) | 28 (36.8) | 29 (31.2) | 0.51 |

| Index admission LOS, d | 5 (3.0, 9.0) | 6 (3.0, 10.5) | 5 (4.0, 9.0) | 0.95 |

| Discharge destination | 0.43 | |||

| Home | 100 (59.2) | 41 (53.9) | 59 (63.4) | |

| Home with care | 35 (20.7) | 17 (22.4) | 18 (19.4) | |

| Skilled nursing facility | 34 (20.1) | 18 (23.7) | 16 (17.2) | |

| Follow up appointment provided prior to discharge | 138 (82.9) | 63 (82.9) | 75 (80.6) | 0.53 |

| Came for appointment | ||||

| Yes | 59 (34.9) | 27 (35.5) | 32 (34.4) | 0.98 |

| No | 63 (37.3) | 29 (38.2) | 34 (36.6) | |

| No appointment provided | 30 (17.8) | 13 (17.1) | 17 (18.3) | |

| Admitted before appointment | 16 (9.5) | 7 (9.2) | 9 (9.7) | |

| Died before appointment | 1 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (1.1) | |

| Duration between discharge and appointment | 14 (7, 28) | 14 (7, 28) | 13 (9, 23) | 0.79 |

| Readmissions within | ||||

| 1 mo | 63 (37.3) | 28 (36.8) | 35 (37.6) | 1 |

| 3 mo | 93 (55.0) | 43 (56.6) | 51 (54.8) | 0.76 |

| 6 mo | 107 (63.3) | 49 (64.5) | 58 (62.4) | 0.87 |

| Problems during initial readmission | ||||

| HE | 36 (21.3) | 21 (42.9) | 15 (26.0) | 0.11 |

| Infection | 28 (16.6) | 14 (28.6) | 14 (24.1) | 1 |

| AKI | 47 (27.8) | 22 (44.9) | 25 (43.1) | 1 |

| GIB | 17 (10.1) | 6 (12.2) | 11 (19.0) | 0.3 |

| Time between discharge and readmit, d | 24 (11, 66) | 22 (11, 59) | 23.5 (12, 57) | 0.63 |

| Readmission LOS, d | 6 (3, 10) | 5 (3, 8) | 6 (4, 12) | 0.06 |

| Alive at | ||||

| 1 mo | 156 (92.3) | 72 (94.7) | 84 (90.3) | 0.39 |

| 3 mo | 137 (81.1) | 66 (86.8) | 71 (76.3) | 0.11 |

| 6 mo | 128 (75.7) | 64 (84.2) | 64 (68.8) | 0.031 |

A follow-up appointment in the outpatient hepatology clinic was provided prior to HD to 83% of the cohort. Median duration to appointment was 14 d and adherence was noted in 59 (35%) patients. The proportion of patients with follow-up scheduled at discharge and those who showed adherence to it were comparable in the intervention and control groups.

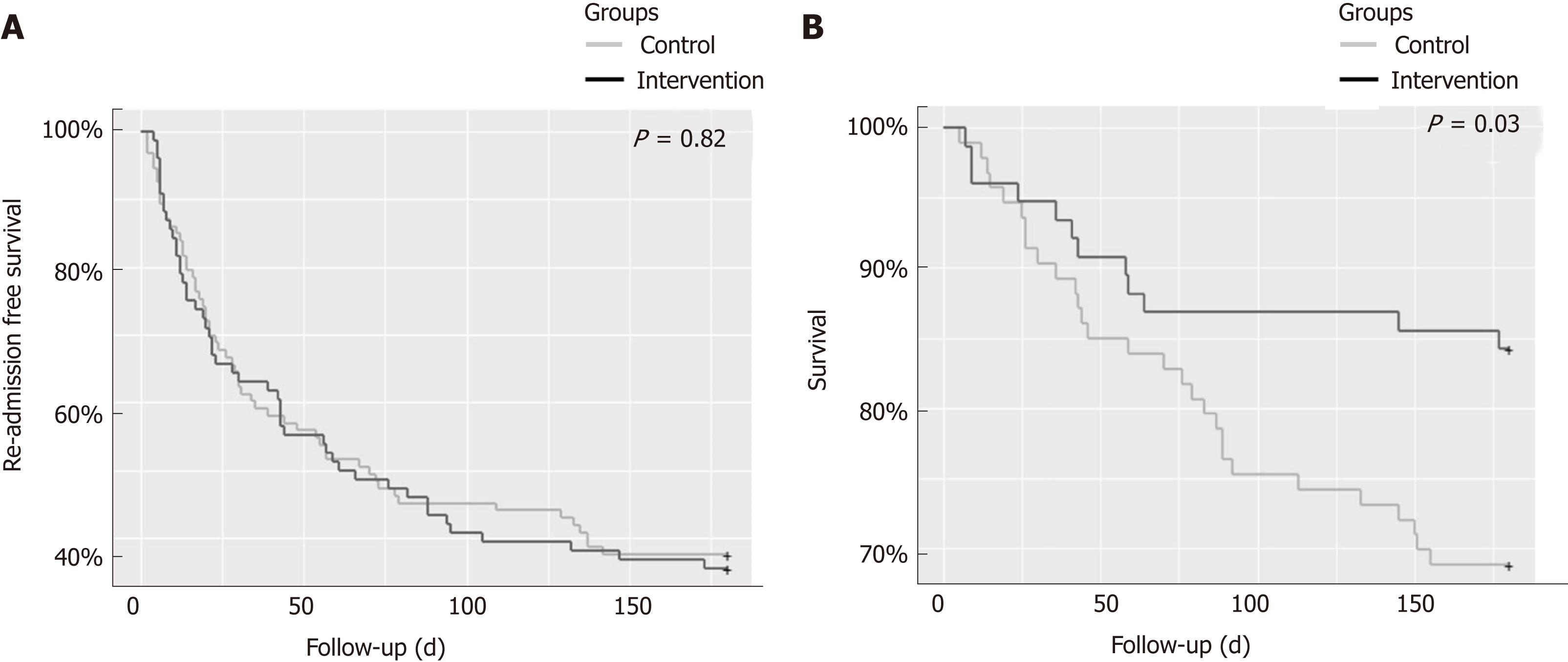

Unplanned hospital readmissions were noted in 37%, 55%, and 63% of the cohort at 1, 3, and 6 mo after index HD, respectively. The median length of re-hospitalization was 6 d. Rates of readmission at each of the intervals were comparable between the intervention and control groups. Median time to readmit was 24 d for the cohort, which was also similar between the two groups. Kaplan-Meier curves comparing RR (P = 0.82) between the two groups are depicted in Figure 2A.

Survival at 1, 3, and 6 mo for the cohort was 92%, 81%, and 76%, respectively. The causes of death in the cohort were septic shock (n = 26), acute renal failure and dyselectrolytemia (n = 4), acute respiratory failure (n = 4), gastrointestinal bleeding (n = 2), cardiac arrhythmia (n = 2), intra-cranial hemorrhage (n = 2), and pulmonary embolism (n = 1). The intervention group showed a tendency towards greater survival compared to the controls at 1 mo (95% vs 90%; P = 0.39) and 3 mo (87% vs 76%; P = 0.11). This difference met statistical significance at 6 mo (84% vs 69%; P = 0.03). Kaplan-Meier curves comparing survival (P = 0.03) for the two groups are depicted in Figure 2B.

On multivariable analysis of demographic, disease, and hospitalization related characteristics only two factors showed a significant association with mortality (Table 2). Patients in the intervention group showed a hazard ratio of 0.4 (95% confidence interval: 0.2-0.82) for mortality when compared to the control group (P = 0.012). Also, with every 1 unit increase in MELD score the hazard for mortality increased 1.05 times (95% confidence interval: 1.01-1.1; P = 0.024). None of the factors showed any significant association with readmissions on multivariate analysis (Table 3).

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Factor | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Intervention vs controls | 0.4 (0.2-0.82) | 0.012 |

| Age | 1.01 (0.99-1.04) | 0.503 |

| Female gender | 1.2 (0.6-2.4) | 0.605 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| EtOH vs HCV | 0.72 (0.29-1.8) | 0.48 |

| NAFLD vs HCV | 0.41 (0.24-2.1) | 0.088 |

| MELD score (for every 1 unit increment) | 1.05 (1.01-1.1) | 0.024 |

| Index hospitalization length of stay (for every 1 d increment) | 0.99 (0.95-1.02) | 0.47 |

| Discharge to home with home care vs home | 1.65 (0.75-3.64) | 0.212 |

| Discharge to SNF vs home | 1.4 (0.56-3.48) | 0.47 |

| Multivariate analysis | ||

| Factor | HR (95%CI) | P value |

| Intervention vs controls | 0.99 (0.66-1.48) | 0.95 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.97-1.01) | 0.39 |

| Female gender | 1.36 (0.87-2.1) | 0.18 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | ||

| EtOH vs HCV | 0.99 (0.13-7.77) | 0.99 |

| NAFLD vs HCV | 1.03 (0.51-2.54) | 0.93 |

| MELD score (for every 1 unit increment) | 1.03 (0.99-1.05) | 0.09 |

| Index hospitalization length of stay (for every 1 d increment) | 0.99 (0.97-1.02) | 0.59 |

| Discharge to home with home care vs home | 1.12 (0.69-2.01) | 0.55 |

| Discharge to SNF vs home | 0.96 (0.51-1.83) | 0.91 |

We demonstrate the value of an outpatient telephone based transitional care program in improving post HD survival in CP. CP who received the intervention were 60% less likely to die than patients in the control group during the 6 mo follow-up. This survival benefit was independent of an effect on RR demonstrating dissociation between these outcomes and raising awareness on the need to reconsider the parameters in use for gauging quality of care provided during hospitalization and subsequent transitional care programs.

Multiple studies demonstrate high RR among CP, which not only levy a financial burden but also negatively impact patient satisfaction, quality of life, and access to liver transplantation[5,11-16]. The most frequent reasons for readmissions such as recurrent hepatic encephalopathy, renal injury, symptomatic ascites, or nosocomial infections are potentially modifiable[4,6,11,13,15-19]. Data from the North American Consortium for the Study of End Stage Liver Diseases showed that more than half of the 1013 study patients were readmitted within 3 mo[6]. Overall 31% had one readmit while 22% patients had two or more. A model based on MELD score, proton pump inhibitor used, and length of stay was developed to try to predict the risk of readmission, but it was not effective in 30% of cases. This suggests that new unexpected changes that developed in the early post discharge period influence patient outcomes. These results make a strong argument for close monitoring of patients in the post discharge period and facilitation of post discharge communication between the patients and healthcare professionals[6,16,20].

RR has been adopted as a key quality measure and reimbursement determinant in some chronic medical conditions (e.g., heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) with a suggestion to include cirrhosis as well in this realm[6]. However, in a large nationwide study that assessed the impact of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction program[21] on outcomes in 115245 patients admitted with heart failure, the rates of both 30 d and 1 yr risk adjusted mortality were found to be markedly increased despite a reduction in readmissions[22]. Thus, there is serious concern over the focus on RR and its reduction and the possible unintended consequences on patient survival in patients with complex disease states[23,24].

Kanwal et al[5] reported results from 122 Veteran Affairs hospitals where CP were offered a follow-up appointment in the hepatology clinic within 7 d of HD. In a 30 d follow-up period, the intervention group was noted to have 1.1 times higher odds for readmission when compared to controls. However, the intervention group showed 40% lower risk for 30 d mortality. This survival benefit has been hypothesized to be secondary to improved coordination of care, better communication with patients, timely adjustment of medications, follow up of outstanding tests, and enabling early readmission when warranted. These factors and efforts are common to our OTTC program and may serve as rationale for the survival benefit noted with our intervention as well.

Tapper et al[9] studied the impact of using checklists at discharge to address appropriate medication use in CP. They noted a 40% reduction in 30 d readmissions; however, 90 d mortality rates were unchanged. It is hypothesized that while improvements in care provided during the hospitalization and at the time of discharge can reduce short term readmits, a more long lasting favorable impact on survival cannot be obtained without close outpatient transitional care. Yet other studies, which focused on setting up robust outpatient caregiver teams for monitoring CP after discharge showed conflicting outcomes. However, their results may have been limited by small sample size[8,10]. A comparison of these studies with ours is offered in Table 4.

| Ref. | Intervention type | Number of patients | Timing of intervention | Unplanned readmission rate | Mortality | |||||

| 1 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | 1 mo | 3 mo | 6 mo | |||||

| Wigg et al[8], 2013 | Chronic disease management program | C:20 T:40 | 12 mo after discharge | C: 0.4/person/yr T: 1/person/yr | 1C: 15% 1T: 10% | |||||

| Morando et al[10], 2013 | Care management checkup model | C: 60 T: 40 | 12 mo after discharge | C: 42% T: 15% | NA | NA | 1C: 46% 1T: 23% | |||

| Tapper et al[9], 2016 | Handheld (1st phase) and electronic (2nd phase) checklists | C: 626 T: 1st: 470 2nd: 624 | Inpatient stay | C: 38% T: 1st: 35% 2nd: 27% | NA | NA | NA | C: 20% T: 1st: 15% 2nd: 21% | NA | |

| Kanwal et al[7], 2016 | Early follow up in clinic | C: 17094 T: 8123 | At discharge | C: 14% T: 15% | NA | NA | C: 5% T: 3% | NA | NA | |

| Current study | Outpatient telephonic transitional care | C: 93 T: 76 | 30 d after discharge | C: 38% T: 37% | C: 55% T: 57% | C: 62% T: 65% | C: 10% T: 5% | C: 24% T: 13% | C: 31% T: 16% | |

At our center, the OTTC was designed to provide individualized, patient specific care and monitor them closely for an additional 30 d after HD. CP often have complex medical needs with rapidly fluctuating parameters and are at high risk for developing multiple complications including infections, renal injury, dyselectroylytemia, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Recurrent hepatic encephalopathy is easily precipitated by any of the above complications or non-adherence to lactulose. After discharge, monitoring these sick patients closely and coordinating their outpatient care, especially for patients who live at great distances from our tertiary referral center, can be challenging for the primary hepatologists. In this regard, having a care coordinator to actively follow up and order additional outpatient diagnostic tests, arrange follow-up visits or timely referrals to specialists, facilitate readmissions when complications arise, and provide medication and disease related counselling to the patients serves as a great source of support for patients, primary hepatologists, and local physicians alike. While these interventions are similar to that suggested in the study by Wigg et al[8], with our larger cohort size and tracking of long term outcomes, a clear survival benefit could be discerned. We hypothesize that the OTTC has no appreciable effect on RR because often the medical complications that develop in decompensated CP cannot be safely managed in an ambulatory setting, and hence readmissions are unavoidable and even beneficial in the care of these ill patients. Early identification of development of complications by the care coordinator may have prompted readmissions, and this in turn may have played a role in mediating the survival benefit. Hence, we argue that the focus of judging quality of CP care should shift away from RR.

Despite its several strengths our study is not without its limitations. This is a single center, retrospective analysis. There is a degree of selection bias because only the CP deemed high risk for readmission were offered OTTC. This determination may have been subjective; however, it was made by the multi-disciplinary inpatient care team after careful consideration of a wide variety of medico-social conditions. One could argue that despite being a higher risk patient group, the intervention improved survival. Expanding the OTTC to include all CP would be the ideal next step in assessing this intervention. Also, because the OTTC interventions were individualized to each patient’s specific needs, the individual interventions were not quantified and compared during the analysis.

In conclusion, CP provided OTTC had a higher 6 mo survival compared to controls despite RR being comparable to controls. Tenets of OTTC that mediate this benefit should be studied, and the potential expansion of OTTC merits explored. The varied impact of the different interventions of OTTC would need to be studied further. RR may not be an appropriate end point to gauge the quality of care provided during hospitalization or subsequent transitional care programs, and hence a focus on post discharge survival should be maintained while adopting and gauging transitional care interventions.

Given the increasing concern about the high rates of readmission in cirrhotic patients (CP) after hospital discharge (HD), focus is now being laid on transitional care interventions to try to mediate a reduction. However, prior studies have also demonstrated a possible adverse impact on patient survival with reduced readmissions. Hence additional studies to comprehensively assess post discharge outcomes in CP and to try to improve them are necessary.

It is alarming but true that nearly 53% of CP get readmitted at least once within 3 mo of HD. This implies a tremendous financial and psychosocial burden to our current healthcare system and measures to improve the prognosis of patients after HD warrant attention.

We developed and evaluated a novel strategy for the care of CP at our center called the outpatient telephonic transitional care program (OTTC). The objectives of this study were to determine the effect of OTTC on survival and readmission rates (RR) at different intervals up to 6 mo after HD in CP and thus further explore the relationship of RR to survival.

In this observational study, CP who were treated in our inpatient hepatology service between March 1 and December 31, 2016 were retrospectively assessed. Those who had received the OTTC program formed the intervention arm, and the rest formed concomitant controls. Survival and RR at 1, 3, and 6 mo after HD were compared between the two groups.

In our study, an overall RR of 55% was noted within 3 mo of HD, which correlates with the national average. Interestingly the RR at 1, 3, and 6 mo were comparable between the intervention and control groups. However, the patients who received the OTTC intervention showed markedly better 6 mo survival compared to the controls with a hazard ratio of 0.4 (95% confidence interval: 0.2-0.82; P = 0.012).

In this study, we demonstrated the beneficial impact of a novel transitional care intervention program that provided a survival benefit to CP after HD. In addition, we highlighted an important dissociation between RR and survival, thus shedding further light on the importance of focusing on survival rather than RR as an outcome while assessing post discharge outcomes in CP. Given the high burden on hospitalizations for CP, our novel and easy to implement intervention may now be adopted at multiple centers to further assess its impact and provide improved care for CP.

Our results reaffirm that CP remain at significant risk for readmission and mortality after HD. A focus on providing appropriate transitional care is essential to improve post discharge outcomes. The OTTC program we describe is minimally resource intensive and can afford a survival benefit to CP. The tenets of the OTTC program should be further explored and assessed in other institutions and settings. Continued emphasis on survival rather than RR is warranted because CP demonstrated a dissociation between these parameters.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Jamali R, Ong J, Zhu YY S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: MaYJ

| 1. | Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:10-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8406] [Cited by in RCA: 8971] [Article Influence: 690.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Volk ML, Piette JD, Singal AS, Lok AS. Chronic disease management for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:14-16.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Tapper EB. Challenge accepted: Confronting readmissions for our patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fagan KJ, Zhao EY, Horsfall LU, Ruffin BJ, Kruger MS, McPhail SM, O'Rourke P, Ballard E, Irvine KM, Powell EE. Burden of decompensated cirrhosis and ascites on hospital services in a tertiary care facility: time for change? Intern Med J. 2014;44:865-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kanwal F, Volk M, Singal A, Angeli P, Talwalkar J. Improving quality of health care for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147:1204-1207. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bajaj JS, Reddy KR, Tandon P, Wong F, Kamath PS, Garcia-Tsao G, Maliakkal B, Biggins SW, Thuluvath PJ, Fallon MB, Subramanian RM, Vargas H, Thacker LR, O'Leary JG; North American Consortium for the Study of End-Stage Liver Disease. The 3-month readmission rate remains unacceptably high in a large North American cohort of patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:200-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 163] [Cited by in RCA: 194] [Article Influence: 21.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kanwal F, Asch SM, Kramer JR, Cao Y, Asrani S, El-Serag HB. Early outpatient follow-up and 30-day outcomes in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2016;64:569-581. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Wigg AJ, McCormick R, Wundke R, Woodman RJ. Efficacy of a chronic disease management model for patients with chronic liver failure. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:850-858.e1-4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tapper EB, Finkelstein D, Mittleman MA, Piatkowski G, Chang M, Lai M. A Quality Improvement Initiative Reduces 30-Day Rate of Readmission for Patients With Cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:753-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Morando F, Maresio G, Piano S, Fasolato S, Cavallin M, Romano A, Rosi S, Gola E, Frigo AC, Stanco M, Destro C, Rupolo G, Mantoan D, Gatta A, Angeli P. How to improve care in outpatients with cirrhosis and ascites: a new model of care coordination by consultant hepatologists. J Hepatol. 2013;59:257-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Ganesh S, Rogal SS, Yadav D, Humar A, Behari J. Risk factors for frequent readmissions and barriers to transplantation in patients with cirrhosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Wong EL, Cheung AW, Leung MC, Yam CH, Chan FW, Wong FY, Yeoh EK. Unplanned readmission rates, length of hospital stay, mortality, and medical costs of ten common medical conditions: a retrospective analysis of Hong Kong hospital data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Berman K, Tandra S, Forssell K, Vuppalanchi R, Burton JR, Nguyen J, Mullis D, Kwo P, Chalasani N. Incidence and predictors of 30-day readmission among patients hospitalized for advanced liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:254-259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Picker D, Heard K, Bailey TC, Martin NR, LaRossa GN, Kollef MH. The number of discharge medications predicts thirty-day hospital readmission: a cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Singal AG, Rahimi RS, Clark C, Ma Y, Cuthbert JA, Rockey DC, Amarasingham R. An automated model using electronic medical record data identifies patients with cirrhosis at high risk for readmission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1335-1341.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J, Rakoski MO, Lok AS. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:247-252. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 303] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 27.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Merli M, Lucidi C, Giannelli V, Giusto M, Riggio O, Falcone M, Ridola L, Attili AF, Venditti M. Cirrhotic patients are at risk for health care-associated bacterial infections. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:979-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Agrawal K, Kumar P, Markert R, Agrawal S. Risk Factors for 30-Day Readmissions of Individuals with Decompensated Cirrhosis. South Med J. 2015;108:682-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Saab S. Evaluation of the impact of rehospitalization in the management of hepatic encephalopathy. Int J Gen Med. 2015;8:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mellinger JL, Volk ML. Multidisciplinary management of patients with cirrhosis: a need for care coordination. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; hospital inpatient value-based purchasing program. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2011;76:26490-26547. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, Cox M, DeVore AD, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Matsouaka RA, Yancy CW, Fonarow GC. Association of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program Implementation With Readmission and Mortality Outcomes in Heart Failure. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:44-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 276] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 56.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Gorodeski EZ, Starling RC, Blackstone EH. Are all readmissions bad readmissions? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:297-298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Press MJ, Scanlon DP, Ryan AM, Zhu J, Navathe AS, Mittler JN, Volpp KG. Limits of readmission rates in measuring hospital quality suggest the need for added metrics. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:1083-1091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |