Published online May 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i5.464

Peer-review started: March 5, 2019

First decision: March 25, 2019

Revised: April 8, 2019

Accepted: April 26, 2019

Article in press: April 28, 2019

Published online: May 27, 2019

Processing time: 84 Days and 1.4 Hours

Variceal hemorrhage is associated with high mortality and is the cause of death for 20–30% of patients with cirrhosis. Nonselective β blockers (NSBBs) or endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) are recommended for primary prevention of variceal bleeding in patients with medium to large esophageal varices. Meanwhile, combination of EVL and NSBBs is the recommended approach for the secondary prevention. Carvedilol has greater efficacy than other NSBBs as it decreases intrahepatic resistance. We hypothesized that there was no difference between carvedilol and EVL intervention for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients.

To evaluate the efficacy of carvedilol compared to EVL for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients

We searched relevant literatures in major journal databases (CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE) from March to August 2018. Patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, regardless of aetiology and severity, with or without a history of variceal bleeding, and aged ≥ 18 years old were included in this review. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy of carvedilol and that of EVL for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension were considered, irrespective of publication status, year of publication, and language.

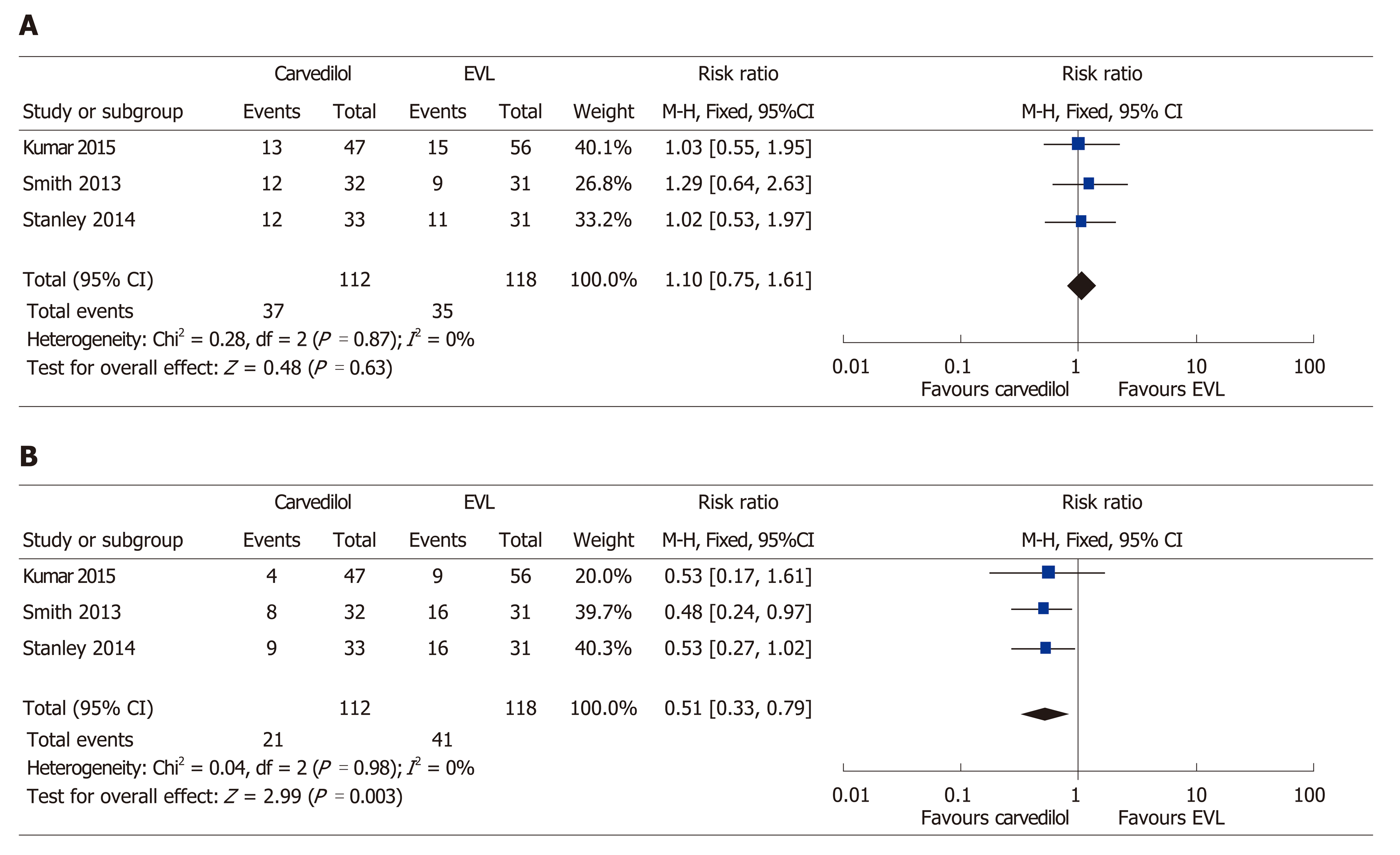

Seven RCTs were included. In four trials assessing the primary prevention, no significant difference was found on the events of variceal bleeding (RR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.37-1.49), all-cause mortality (RR: 1.10, 95%CI: 0.76-1.58), and bleeding-related mortality (RR: 1.02, 95%CI: 0.34-3.10) in patients who were treated with carvedilol compared to EVL. In three trials assessing secondary prevention, there was no difference between two interventions for the incidence of rebleeding (RR: 1.10, 95%CI: 0.75-1.61). The fixed-effect model showed that, compared to EVL, carvedilol decreased all-cause mortality by 49% (RR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.33-0.79), with little or no evidence of heterogeneity.

Carvedilol had similar efficacy to EVL in preventing the first variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients with esophageal varices. It was superior to EVL alone for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in regard to all-cause mortality reduction.

Core tip: This study was an updated meta-analysis of primary prevention and the first meta-analysis of secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Seven relevant randomized controlled trials were included. Based on the pooled analysis, carvedilol had similar efficacy to endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) in preventing the first variceal hemorrhage in cirrhosis patients with esophageal varices. Carvedilol was superior to EVL for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in regard to all-cause mortality reduction by 49% (RR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.33–0.79).

- Citation: Dwinata M, Putera DD, Adda’i MF, Hidayat PN, Hasan I. Carvedilol vs endoscopic variceal ligation for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding: Systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(5): 464-476

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i5/464.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i5.464

Variceal hemorrhage is associated with high mortality and is the cause of death for 20–30% of patients with cirrhosis[1]. The use of nonselective β blockers (NSBBs) or endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is recommended to prevent primary variceal bleeding in patients with medium to large esophageal varices[2]. Meanwhile, a combination of EVL and NSBBs (i.e., propranolol or nadolol, with carvedilol as an alternative) is the standard approach to prevent rebleeding. Treatment selection is based on the availability of local resources and expertise, patient characteristics and preferences, contraindications, and side-effects[3] .

NSBBs reduce portal pressure by decreasing cardiac output (β-1 effect) and, more importantly, by initiating splanchnic vasoconstriction (β-2 effect), thus causing a reduction in portal vein pressure. A decrease in the hepatic venous pressure gradient of < 20% or even < 10% from baseline significantly minimizes the risk of the first variceal hemorrhage[4,5].

Carvedilol, given its additional α-blocking component, has been reported to have higher efficacy than other NSBBs in reducing intrahepatic vascular resistance. A significant difference in overall mortality, bleeding-related mortality, and upper gastrointestinal bleeding between patients treated with carvedilol or EVL to prevent first variceal hemorrhage was not seen in a previous systematic review. However, only two primary prevention studies were included in the review. On the other hand, until present, there is no systematic review or meta-analysis comparing carvedilol with EVL for the secondary prevention of variceal bleeding[6-8].

We hypothesized that there was no difference between carvedilol and EVL intervention for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients. In many developing countries, EVL intervention is only available at specific secondary or tertiary healthcare centres. We presumed that carvedilol may be the best prevention strategy of variceal bleeding, especially in hospitals that are unable to offer EVL. Therefore, we performed this review with the inclusion of subsequent trials to summarize and update the evidence.

The study objective was to compare the efficacy of carvedilol and EVL for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients

Patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension, regardless of aetiology and severity, with or without a history of variceal bleeding, and aged ≥ 18 years old were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy of carvedilol and that of EVL for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension were considered, irrespective of publication status, year of publication, and language.

A comparison of the primary outcome (bleeding events, all-cause mortality, and bleeding-related mortality) was made for patients with and without a history of variceal bleeding. A bleeding incident was defined as hematemesis or melena and was detected by endoscopic procedure or signs of hemorrhage. Bleeding from the band ligation was also counted. All-cause mortality meant death that occurred in each of the included studies and until follow-up completion.

Serious adverse events, non-serious adverse events, and compliance and treatment failure were secondary outcomes. An adverse event was considered be serious if it led to death, was life-threatening, or caused persistent disability.

Two independent reviewers searched the Medline, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and EMBASE journal databases from March to August 2018 (Table 1). The reference lists of the retrieved articles were perused for potentially relevant studies. Abstracts and other gray literatures were also included through a manual and electronic search of the clinical trial registries and electronic databases.

| Journal database | Search Terms | Articles |

| CENTRAL | (Cirrhosis OR “esophageal varices” OR “oesophageal varices”) AND (carvedilol) AND (ligation OR “variceal band ligation” OR “endoscopic variceal ligation” OR VBL OR EVL) | 20 |

| MEDLINE | (Cirrhosis OR “esophageal varices” OR “oesophageal varices”) AND (carvedilol) AND (ligation or “variceal band ligation” OR “endoscopic variceal ligation” OR VBL OR EVL) | 5 |

| EMBASE via Ovid | Cirrhosis AND Carvedilol AND Ligation | 3 |

| A manual search of abstracts and citation index from identified paper’s reference list and via https://library.sydney.edu.au/ | “portal hypertension”, “cirrhosis”, “carvedilol”, “endoscopic variceal ligation” | 54 |

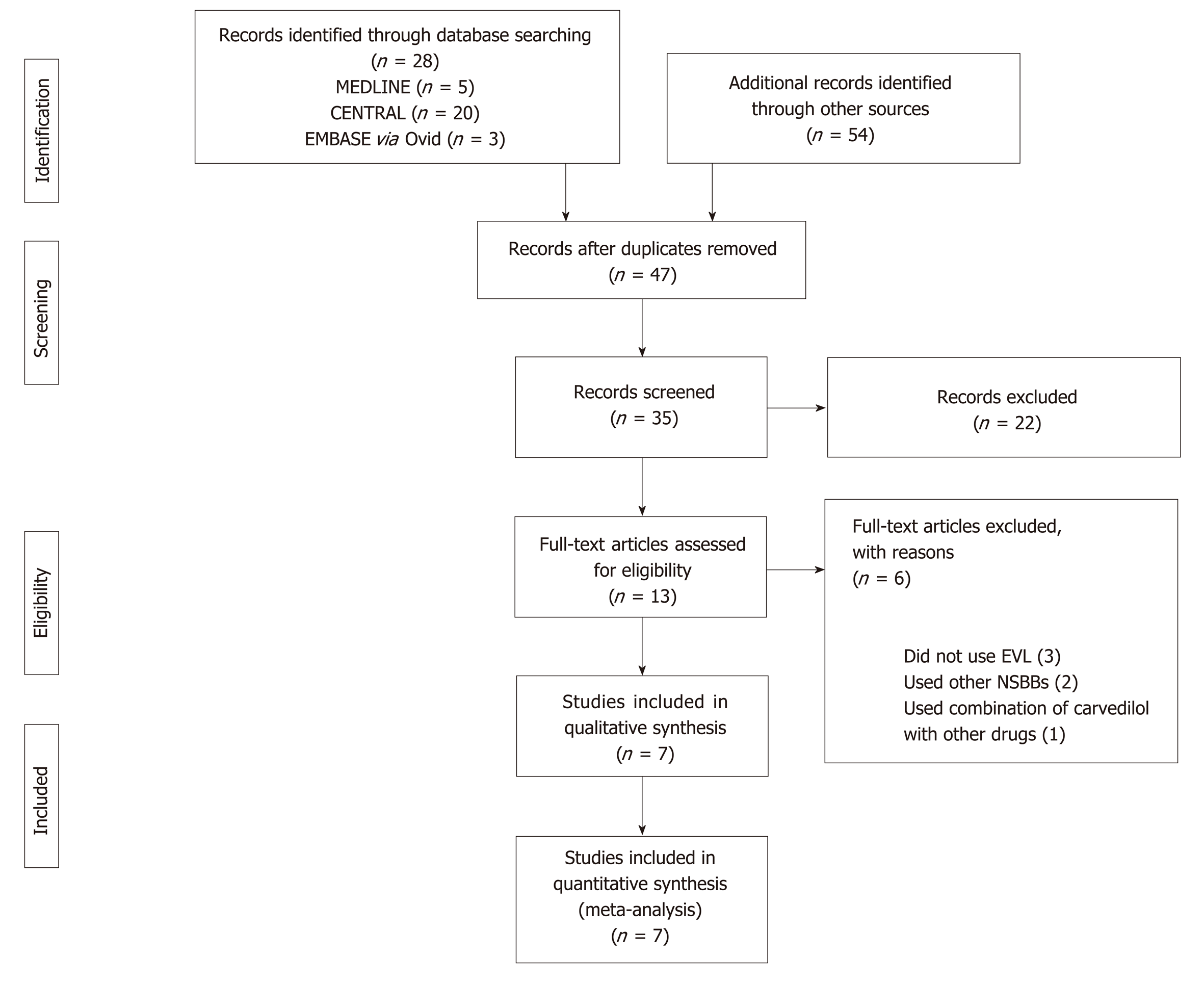

Relevant studies, screened based on the title and abstract, were selected after conducting an electronic search. Studies on animals and review articles were excluded. Disagreement was resolved through discussion, failing which a third reviewer was consulted. The study selection process was plotted using a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. The relevant studies were independently appraised using an Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine critical appraisal tool.

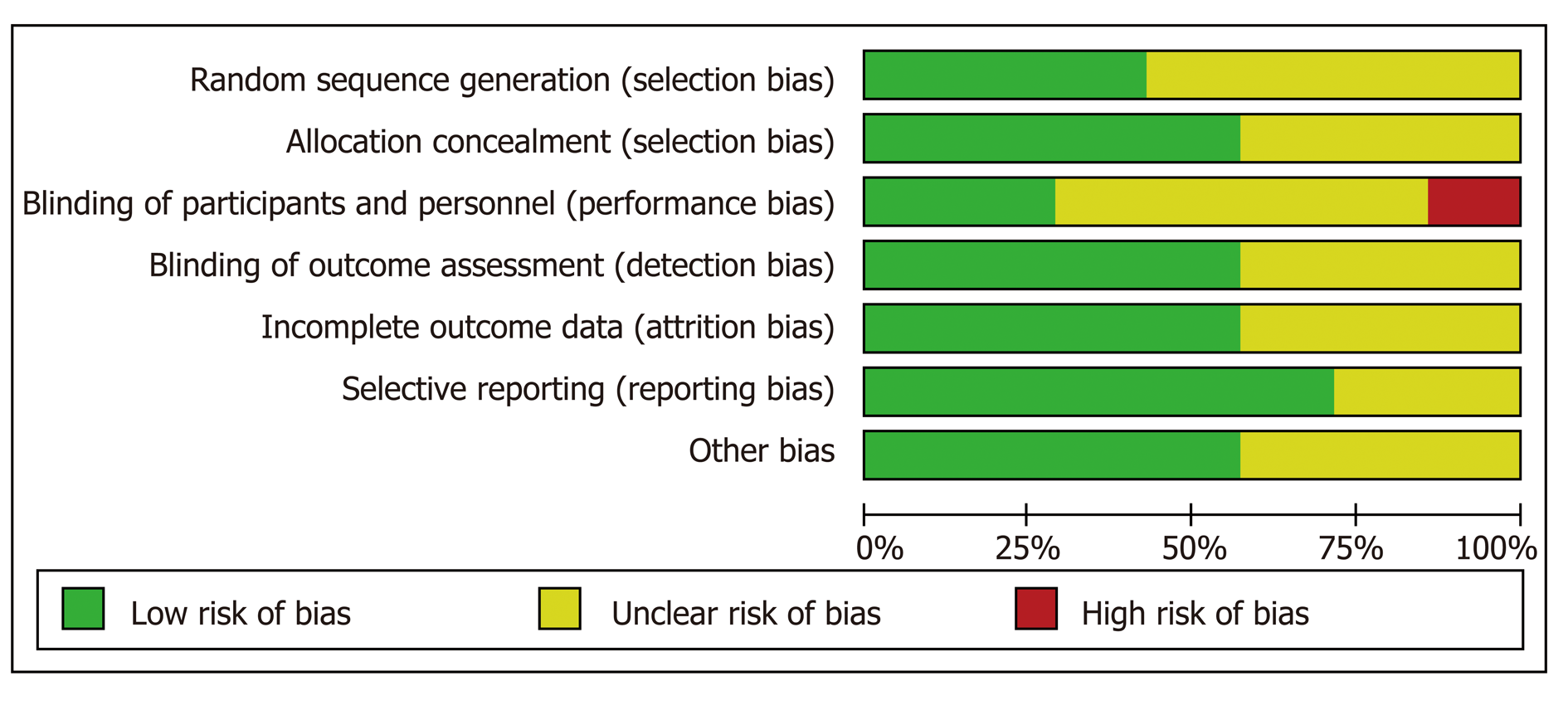

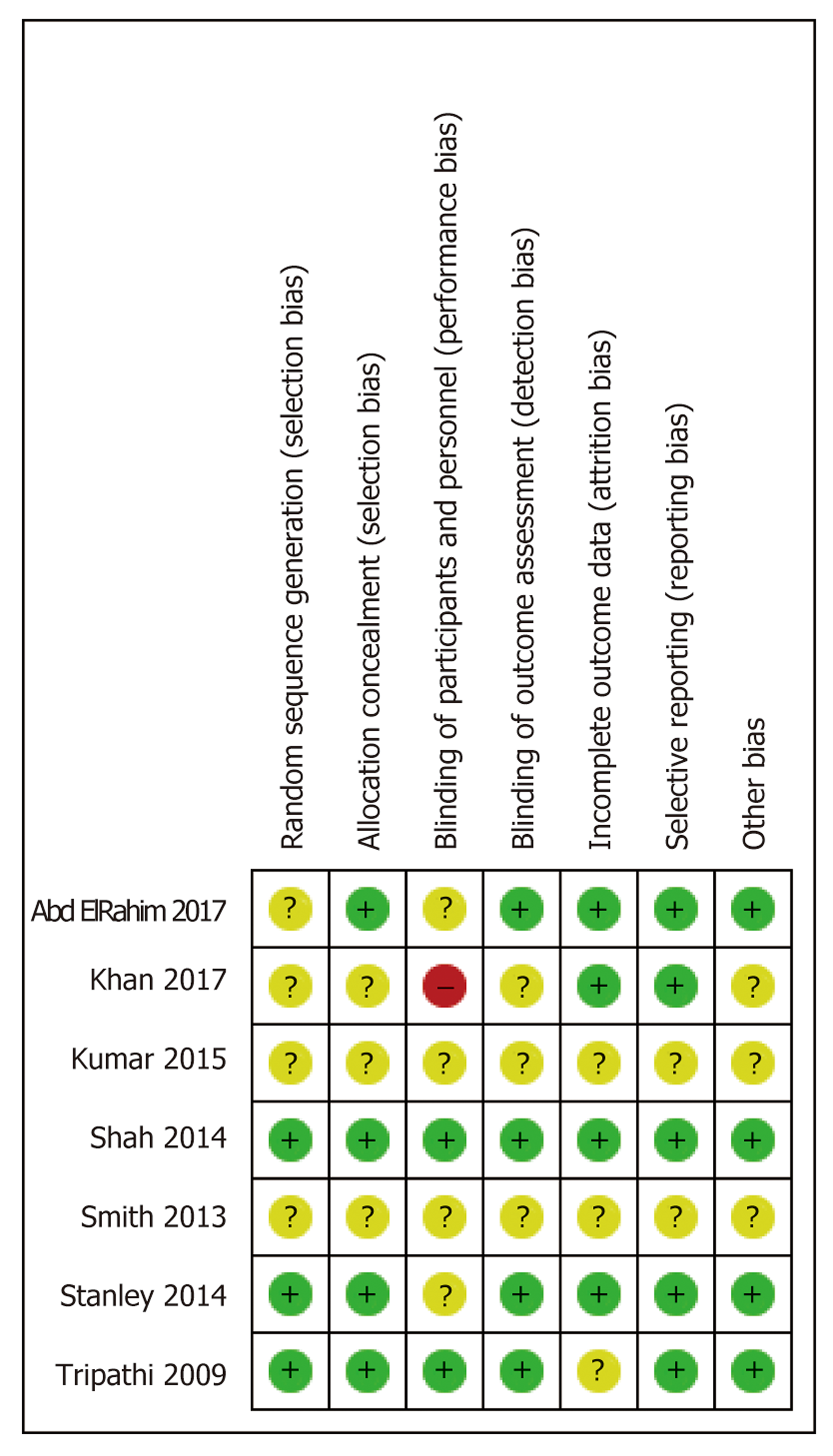

Risk of bias was independently determined using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. The data were then included in a table. Risk of bias was classified as low, high, or unclear. Disagreement was resolved through discussion, failing which a third reviewer was consulted.

Risk ratios (RR) and 95%CI were used to calculate the dichotomous data. RRs with 95%CI were used as relevant effect measures for variceal bleeding, all-cause mortality, and bleeding-related mortality. Statistical analysis was performed according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions and using Review Manager® version 5.3 guidelines.

A random-effects model was chosen a priori for the entire analysis. The χ2 and I2 statistics were calculated. P < 0.10 or I2 of > 60% was considered to indicate substantial heterogeneity. I2 of > 40% indicated moderate heterogeneity. Analysis was carried out using a fixed-effects model, in the absence of statistically significant heterogeneity, and a random-effects model in the case of significant heterogeneity. For the subgroup analysis, P < 0.05 was considered to denote a difference that was statistically significant between the subgroups. We assessed the quality of evidence using Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) approach and created ‘Summary of findings’ table.

Our initial intention was to perform sensitivity analysis of heterogeneity found in the pooled studies through the exclusion of studies with low-quality results. However, this did not occur owing to a paucity of data. Subgroup analysis was conducted of the primary bleeding outcomes based on the grade of varices.

Five, twenty, and three relevant references were identified in the Medline, CENTRAL, and EMBASE via Ovid databases, respectively. Fifty-four of them were selected through a manual search of the references lists in the identified papers. Thirty-five studies were duplicates and were removed. The abstracts were also filtered, leading to the removal of a further 22 studies that met the exclusion criteria for various reasons; i.e., carvedilol or EVL were not used as interventions, the study design was not an RCT, or the research had been withdrawn or was ongoing. Thirteen full-text studies were assessed for eligibility. Six of these were excluded, primarily because either EVL or carvedilol were not evaluated, or carvedilol was assessed but in combination with other drugs (Figure 1).

Seven RCTs were included in the current study. Primary prevention was assessed in four trials[9-12], and secondary prevention was evaluated in three[9-15] (Table 2). Three of the studies were deemed to be of fair quality, and the remaining one was determined to be of low quality when measured using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (Figures 2 and 3).

| Ref. | History of variceal bleeding | Treatment groups | Age (mean ± SD, yr) | n | Dosage / method | Follow up(mo) | |

| Tripathi et al[9] | No | Carvedilol | 54.2 ± 9.4 | 77 | 6.25 mg (starting dose) daily, with target dose of 12.5 mg daily | 24 | |

| EVL | 54.5 ±11.1 | 75 | Every two weeks until eradication | 24 | |||

| Shah et al[10] | No | Carvedilol | 48.3 ± 11.3 | 82 | 6.25 mg daily, with target dose of 6.25 mg twice a day | up to 24 | |

| EVL | 47.2 ± 13.2 | 86 | Every three weeks until eradication | up to 24 | |||

| Khan et al[12] | No | Carvedilol | 52.1 ± 14.7 | 125 | 12.5 mg daily | 6 | |

| EVL | 54.1±14.3 | 125 | Not mentioned | 6 | |||

| Abd ElRahim et al[11] | No | Carvedilol | 51.2 ± 11.0 | 84 | starting dosage of 6.25 mg daily, titrated up every 4 days to reach up to 12.5–50 mg | up to 12 | |

| EVL | 50.6 ± 5.9 | 88 | Every two weeks until eradication | up to 12 | |||

| Smith et al[15] | Yes | Carvedilol | 51 ± 10.9 | 32 | 6.25 mg daily, with target dose 12.5 of mg daily | 29 | |

| EVL | 50 ± 13.0 | 31 | Not mentioned | 29 | |||

| Stanley et al[14] | Yes | Carvedilol | 51.4 ± 10.8 | 33 | 6.25 mg daily, with target dose 12.5 of mg daily | up to 60 | |

| EVL | 49.6 ± 12.87 | 31 | Every two weeks until eradication | up to 60 | |||

| Kumar et al[13] | Yes | Carvedilol | 44.1 ± 8.5 (overall) | 47 | Not mentioned | 11.1 - 21.7 | |

| EVL | 44.1 ± 8.5 (overall) | 56 | Not mentioned | 11.1 - 21.7 | |||

In the four studies that assessed primary prevention, 368 patients were randomised to carvedilol and 374 patients to EVL. The length of follow-up in the studies varied from 6–24 mo. The mean age of the participants was 47–52 years. Majority of study subjects in two of the trials were classified as Child class A (Child-Pugh Score) and as Child class C in one trial, while cirrhosis was not classified in the fourth research. Most of the trials included cirrhosis patients with medium to large varices (grade II or higher)[10-12], but one study included patients with grade I and II esophageal varices[13]. There was no difference for bleeding incidence (RR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.37–1.49), all-cause mortality (RR of 1.10, 95%CI: 0.76-1.58), and bleeding-related mortality (RR: 1.02, 95%CI: 0.34–3.10) between carvedilol group and EVL (Figure 4 A-C). Subgroup analysis was conducted on participants with medium to large esophageal varices (grade II or larger), and the differences between the groups were also without statistical significance (RR: 0.89, 95%CI: 0.55–1.43). There was little to no evidence of subgroup differences between Grade I and Grade II varices or higher (χ2 = 2.19, degrees of freedom = 1, P = 0.14). The differences might be moderate (I2 = 54.4%) (Figure 4A).

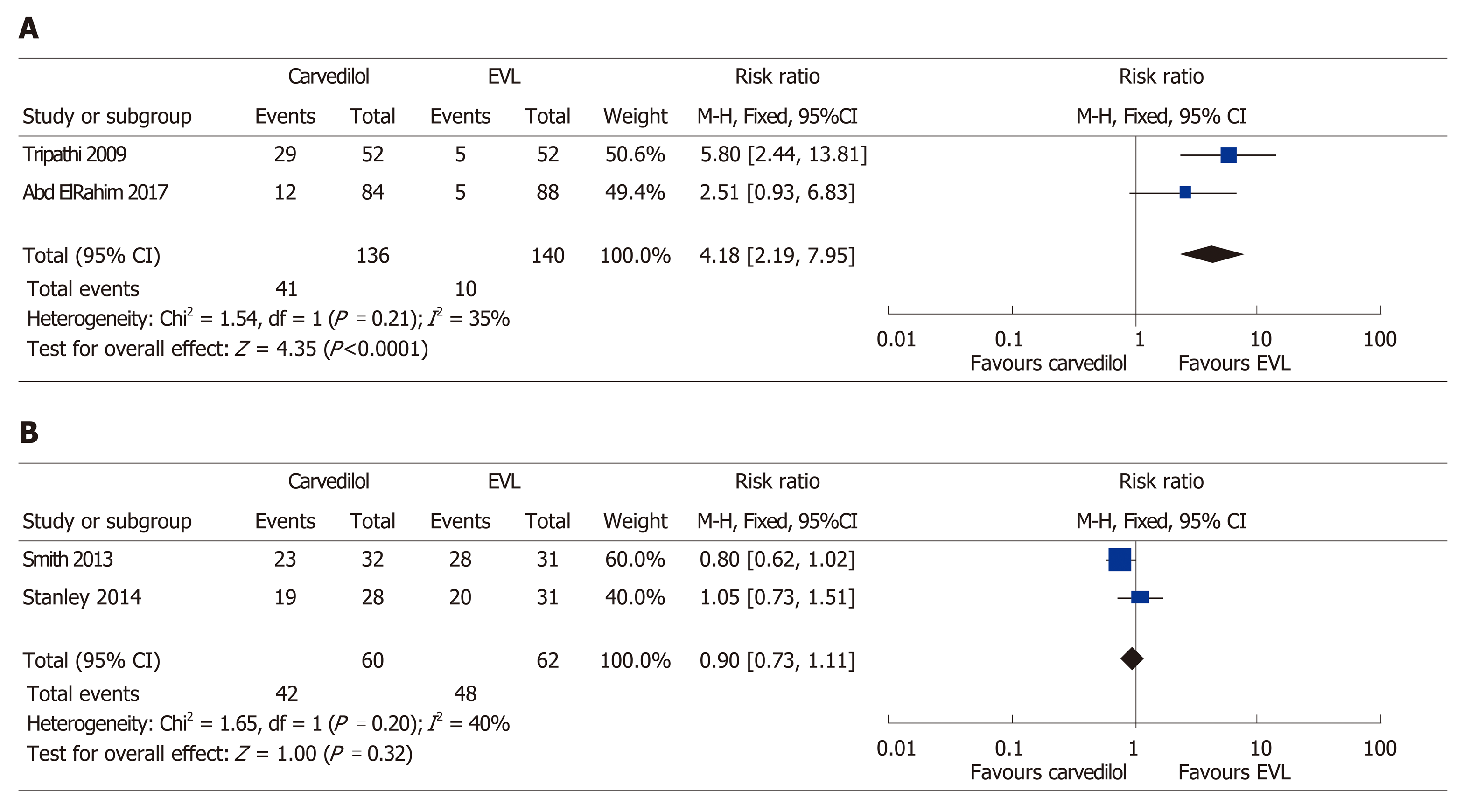

During the follow-up, hypotension was seen to be the most common side-effect of carvedilol treatment, followed by bradycardia, and asthmatic attack[11]. Following analysis of the primary prevention studies, a 4.18 times higher risk of treatment-related side-effects was attributed to the carvedilol group (95%CI: 2.19–7.95, P ≤ 0.001) (Figure 5 A). By contrast, EVL was shown to be associated with serious adverse events (i.e., chest pain that required medication) in 20% of the participants, compared to 0% of the patients in the carvedilol group (P ≤ 0.001) in another study[10]. However, subjects in the carvedilol group experienced more non-serious adverse events, including dyspnea and nausea (P = < 0.001). Patient compliance with the treatment was similar between the two groups when the primary prevention studies were analyzed (P = 0.32) (Figure 5 B).

The randomization of 230 participants took place in the three trials in which secondary prevention was assessed. The mean age of the participants in the studies ranged from 44–52 years. A median Child-Pugh score of 9 was attained, with a mean follow-up period of 16–30 mo. There was no difference between the two interventions with respect to rebleeding incidence (RR: 1.10, 95%CI: 0.75–1.61) (Figure 6 A). The fixed-effects model showed that carvedilol decreased all-cause mortality by 49% (RR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.33–0.79) (Figure 6 B) without significant heterogeneity (χ2 = 0.04, P = 0.980, I2 = 0%). Elsewhere, in a study on secondary prevention, Stanley et al[14] reported a similar incidence of serious adverse events in both intervention groups (P = 0.97). However, Kumar et al[13] noted considerably more side-effects (28%) due to carvedilol compared to EVL (2%) (P ≤ 0.05).

In this study, we found no significant differences in the incidence of variceal bleeding, all-cause mortality, and bleeding-related mortality between carvedilol vs EVL for primary prevention strategy. This finding was consistent with the subsequent subgroup analysis of participants with medium to large esophageal varices (grade II or higher). This finding was also similar to that reported in a previous meta-analysis[8], but the current study extended to an analysis of the side-effects that arose from the interventions and patient compliance with the medication.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first meta-analysis to have assessed the efficacy of carvedilol vs that of EVL for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding. Based on our pooled analysis, although there was no significant difference regarding incidence, carvedilol may be superior compared to EVL by significantly reducing all-cause mortality. Unfortunately, the relevant data needed to elucidate this finding were lacking in the review. In a study conducted by Stanley, most deaths in the carvedilol group were related to bleeding (15%), whereas only 3% of deaths were due to bleeding in the EVL group. None of the patients in the carvedilol group died of liver-related causes not due to bleeding, whereas the latter was responsible for the deaths of six of the 31 (19%) patients in the EVL group. It is assumed that this result can be explained by the systematic effect of carvedilol in reducing portal pressure in patients with cirrhosis.

Carvedilol, an NSBB with weak intrinsic anti-α1-adrenergic activity, is known to effect a reduction in portal pressure with added vasodilatory α-adrenergic blocking activity. The α1-adrenergic receptor located in the splanchnic vascular smooth muscles and vascular smooth muscle at other sites, such as the genitourinary tract. Blocking the α1-adrenergic receptors leads to a reduction in intrahepatic vascular tone. Therefore, the α1- and β-receptor-blocking properties of carvedilol can lead to superior reduction in portal pressure compared to conventional NSBBs (i.e., propranolol or nadolol)[16].

The current recommendation for the prevention of variceal rebleeding in cirrhosis patients is to use a combination of EVL and NSBBs (i.e., propranolol or nadolol). This study revealed that carvedilol is superior to EVL alone for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in regard to all-cause mortality reduction. Regarding this finding, we encourage that RCTs comparing efficacy of carvedilol vs combination therapy of EVL and NSBBs should be conducted to strengthen the evidence. This current study finding may be of use to physicians working in rural areas or hospitals where an EVL intervention is unlikely[17].

In the primary prevention studies, patient compliance was similar in both groups despite a greater number of side-effects being seen in the carvedilol group. This indicates that the side-effects were nevertheless tolerable to the participants. In the secondary prevention studies, the data on serious adverse events and side-effects of both interventions were still insufficient. Further studies are needed to comprehensively assess the side-effects of each intervention.

There are several limitations in this systematic review and meta-analysis that bear mentioning. First, we could not retrieve complete data from some included studies which hindered us to do some subgroup analysis, such as subgroup analysis of cirrhosis severity or numbers of EVL procedure performed. Most of the included studies also did not perform specific analysis regarding this particularly topic. Second, the numbers of available clinical trials are relatively limited which also hindered us to perform sensitivity analysis for this study.

The quality of evidence of primary prevention for variceal bleeding is low. The quality is reduced due to lack of blinding in the included studies. On the contrary, the quality of evidence for the all-cause mortality and the bleeding-related mortality in primary prevention is high as the included studies showed low risk of bias. The quality of evidence of secondary prevention for rebleeding is low, because some of the included studies showed unclear methods while conducting the studies (Table 3).

| Outcomes | Relative effect | Participants | Quality of the evidence | Comments |

| (95%CI) | (studies) | (GRADE) | ||

| Variceal bleed in primary prevention (Grade I) | RR 0.38 | 250 | ++−− | Benefit for Carvedilol group |

| (0.15-0.93) | (1 Study) | low | ||

| Variceal bleed in primary prevention (Grade II) | RR 0.92 | 492 | +++− | |

| (0.42-2.41) | (3 Studies) | moderate | ||

| All-cause mortality in primary prevention | RR 1.10 | 320 | ++++ | |

| (0.76-1.58) | (2 Studies) | high | ||

| Bleeding-related mortality in primary prevention | RR 1.02 | 320 | ++++ | |

| (0.34-3.10) | (2 Studies) | high | ||

| Side effect of treatment in primary prevention | RR 4.18 | 276 | +++− | Benefit for EVL group |

| (2.19-7.95) | (2 Studies) | moderate | ||

| Compliance in primary prevention | RR 0.90 | 122 | +++− | |

| (0.73-1.11) | (2 Studies) | low | ||

| Rebleeding events in secondary prevention | RR 1.10 | 230 | ++−− | |

| (0.75-1.61) | (3 Studies) | low | ||

| All-cause mortality in secondary prevention | RR 0.51 | 230 | ++−− | Benefit for Carvedilol group |

| (0.33-0.79) | (3 Studies) | low |

In conclusion, carvedilol had similar efficacy to EVL in preventing the first variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients with esophageal varices. We considered that carvedilol was superior to EVL alone for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in regard to all-cause mortality reduction.

Variceal hemorrhage is associated with high mortality and is the cause of death for 20%–30% of patients with cirrhosis. Either traditional nonselective β blockers (NSBBs) (i.e. propranolol or nadolol), carvedilol, or endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is recommended for primary prevention of variceal bleeding in patients with medium to large esophageal varices. Meanwhile, combination of EVL and NSBBs is the recommended approach for the secondary prevention. Carvedilol has greater efficacy than other NSBBs as it decreases intrahepatic resistance. We hypothesized that there was no difference between carvedilol and EVL intervention for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients.

Some of the major drawbacks of EVL are invasive, costly, and unavailable in many areas, especially in developing countries. A better understanding of the efficacy of carvedilol compared to EVL might provide less invasive and more accessible prevention strategy for variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients.

We conducted this meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of carvedilol compared to EVL for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices

We searched relevant literatures in major journal databases (CENTRAL, MEDLINE, and EMBASE) from March to August 2018. Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy of carvedilol and that of EVL for primary and secondary prevention of variceal bleeding and mortality in patients with cirrhosis and portal hypertension were considered, irrespective of publication status, year of publication, and language.

Seven RCTs were included in this meta-analysis. For primary prevention strategy, we found no significant difference between carvedilol and EVL on the events of variceal bleeding, all-cause mortality, and bleeding-related mortality. For secondary prevention strategy, we found no difference between two interventions for the incidence of rebleeding. Interestingly, compared to EVL, carvedilol decreased all-cause mortality by 49% (RR: 0.51, 95%CI: 0.33-0.79), with little or no evidence of heterogeneity.

Carvedilol had similar efficacy to EVL in preventing the first variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients with esophageal varices. In clinical practice, the use of carvedilol or EVL for prevention of first variceal bleeding may depends on physicians’ and patients’ preference. For prevention of rebleeding, we considered that carvedilol was superior to EVL alone in regard to all-cause mortality reduction.

This study demonstrated significant benefit of using carvedilol for secondary prevention of variceal bleeding in cirrhosis patients. We highly suggest that future clinical trials should compare between carvedilol and combination of EVL and traditional NSBBs (i.e., propranolol or nadolol) or carvedilol to enrich our understanding about efficacy of carvedilol for the prevention of esophageal varices rebleeding.

The authors are grateful to Jonathan Haposan at the Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh, for his invaluable assistance in assisting with the statistical analysis and data interpretation.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Indonesia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lan C, Maria Streba LLA S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Kasper D, Fauci A, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, Loscalzo J. Harrison's principles of internal medicine. 19th ed. New York: Mc Graw Hill 2015; 2062-2064. |

| 2. | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1438] [Article Influence: 179.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | de Franchis R; Baveno V Faculty. Revising consensus in portal hypertension: report of the Baveno V consensus workshop on methodology of diagnosis and therapy in portal hypertension. J Hepatol. 2010;53:762-768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1066] [Cited by in RCA: 1027] [Article Influence: 68.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Turnes J, Garcia-Pagan JC, Abraldes JG, Hernandez-Guerra M, Dell'Era A, Bosch J. Pharmacological reduction of portal pressure and long-term risk of first variceal bleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:506-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 165] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Villanueva C, Aracil C, Colomo A, Hernández-Gea V, López-Balaguer JM, Alvarez-Urturi C, Torras X, Balanzó J, Guarner C. Acute hemodynamic response to beta-blockers and prediction of long-term outcome in primary prophylaxis of variceal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:119-128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Sinagra E, Perricone G, D'Amico M, Tinè F, D'Amico G. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the haemodynamic effects of carvedilol compared with propranolol for portal hypertension in cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:557-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gluud LL, Krag A. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers for primary prevention in oesophageal varices in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;CD004544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li T, Ke W, Sun P, Chen X, Belgaumkar A, Huang Y, Xian W, Li J, Zheng Q. Carvedilol for portal hypertension in cirrhosis: systematic review with meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e010902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tripathi D, Ferguson JW, Kochar N, Leithead JA, Therapondos G, McAvoy NC, Stanley AJ, Forrest EH, Hislop WS, Mills PR, Hayes PC. Randomized controlled trial of carvedilol versus variceal band ligation for the prevention of the first variceal bleed. Hepatology. 2009;50:825-833. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 216] [Cited by in RCA: 184] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Shah HA, Azam Z, Rauf J, Abid S, Hamid S, Jafri W, Khalid A, Ismail FW, Parkash O, Subhan A, Munir SM. Carvedilol vs. esophageal variceal band ligation in the primary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a multicentre randomized controlled trial. J Hepatol. 2014;60:757-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abd ElRahim AY, Fouad R, Khairy M, Elsharkawy A, Fathalah W, Khatamish H, Khorshid O, Moussa M, Seyam M. Efficacy of carvedilol versus propranolol versus variceal band ligation for primary prevention of variceal bleeding. Hepatol Int. 2018;12:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Khan MS, Majeed A, Ghauri F, Asghar U, Waheed I. Comparison of carvedilol and esophageal variceal band ligation for prevention of variceal bleed among cirrhotic patient. Pak J Health Med Sci. 2017;11:1046–1048. |

| 13. | Kumar P, Kumar R, Saxena KN, Misra SP, Dwivedi, M. Secondary prophylaxis of variceal hemorrhage: a comparative study of band ligation, carvedilol, and propranolol plus isosorbide mononitrate. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2015;34:1–104. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Stanley AJ, Dickson S, Hayes PC, Forrest EH, Mills PR, Tripathi D, Leithead JA, MacBeth K, Smith L, Gaya DR, Suzuki H, Young D. Multicentre randomised controlled study comparing carvedilol with variceal band ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1014-1019. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Smith LA, Dickson S, Hayes PC, Tripathi D, Ferguson W, Forrest EH, Gaya DR, Mills PR, Suzuki H, Young D, Stanley AJ. Multicentre randomised controlled study comparing carvedilol with endoscopic band ligation in the prevention of variceal rebleeding. Gut. 2013;62:A1-A2. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Karadsheh Z, Allison H. Primary prevention of variceal bleeding: pharmacological therapy versus endoscopic banding. N Am J Med Sci. 2013;5:573-579. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Brunner F, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Prevention and treatment of variceal haemorrhage in 2017. Liver Int. 2017;37 Suppl 1:104-115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |