Published online Apr 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i4.370

Peer-review started: February 13, 2019

First decision: March 14, 2019

Revised: March 21, 2019

Accepted: April 8, 2019

Article in press: April 8, 2019

Published online: April 27, 2019

Processing time: 73 Days and 11.1 Hours

Patients with cirrhosis deemed ineligible for liver transplantation are usually followed in general hepatology or gastroenterology clinics, with the hope of re-evaluation once they meet the appropriate criteria. Specific strategies to achieve liver transplant eligibility for these patients have not been studied.

To assess clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with future liver transplant eligibility among patients initially considered ineligible.

This is a retrospective study of patients with cirrhosis considered non-transplant eligible, but without absolute contraindications, who were scheduled in our transitional care liver clinic (TCLC) after discharge from an inpatient liver service. Transplant candidacy was assessed 1 year after the first scheduled TCLC visit. Data on clinical and sociodemographic factors were collected.

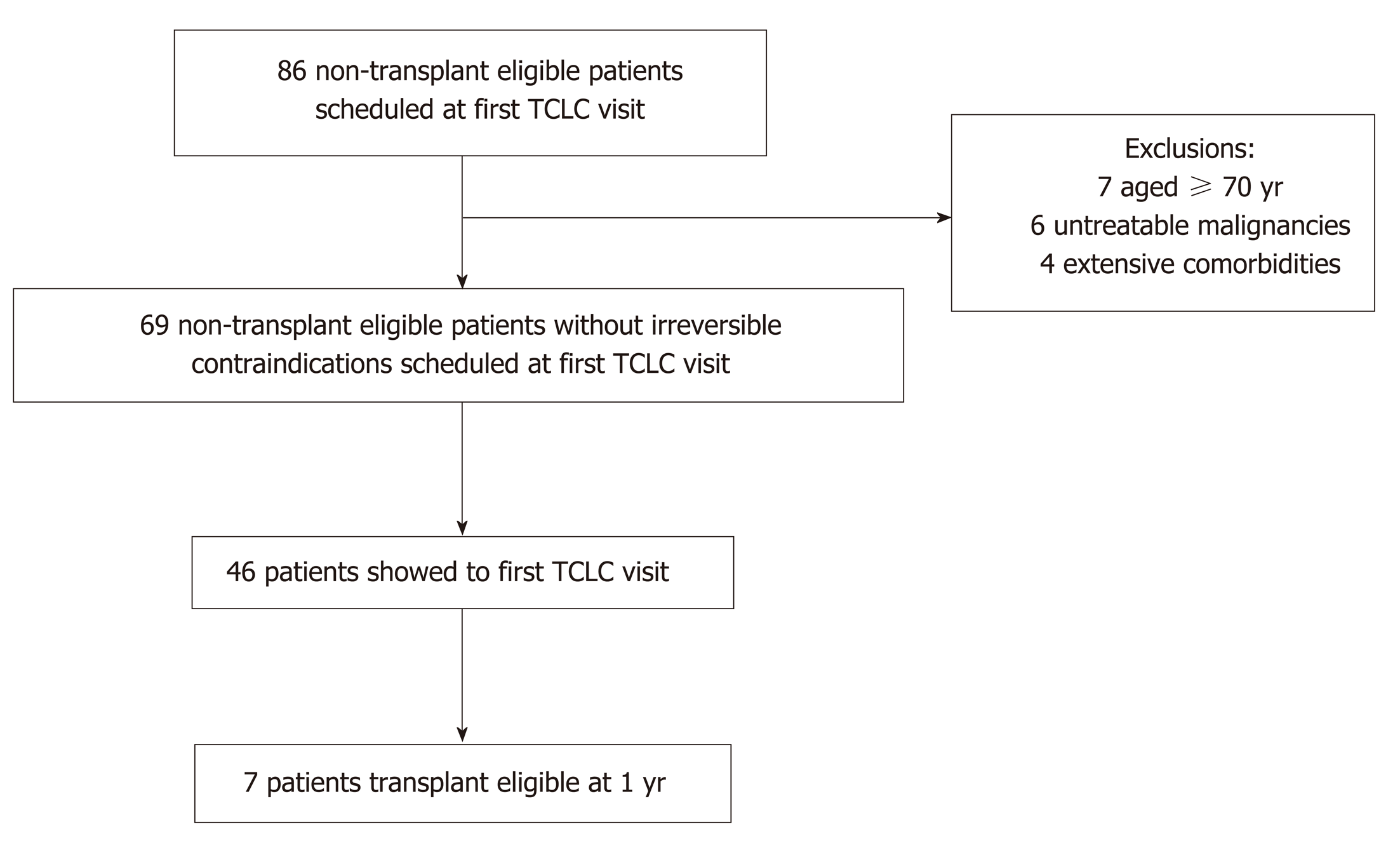

Sixty-nine patients were identified and the vast majority were Caucasian men with alcoholic cirrhosis. 46 patients (67%) presented to the first TCLC visit. Seven of 46 patients that showed to the first TCLC visit became transplant candidates, while 0 of 23 patients that no-showed did (15.2% vs 0%, P = 0.08). Six of 7 patients who showed and became transplant eligible were accompanied by family or friends at the first TCLC appointment, compared to 13 of 39 patients who showed and did not become transplant eligible (85.7% vs 33.3%, P = 0.01).

Patients who attended the first post-discharge TCLC appointment had a trend for higher liver transplant eligibility at 1 year. Being accompanied by family or friends during the first TCLC visit correlated with higher liver transplant eligibility at 1 year (attendance by family or friends was not requested). Patient and family engagement in the immediate post-hospitalization period may predict future liver transplant eligibility for patients previously declined.

Core tip: Being declined as a liver transplant candidate is not always an irreversible decision, but there is limited information about predictors for eventually achieving liver transplant eligibility. This study shows that among patients who were found not to be transplant candidates, those who presented to their post hospital discharge liver clinic appointment with family and friends had a higher chance of liver transplant eligibility within one year. This finding suggests the importance of engaging family and friends in the complex care of patients with cirrhosis.

- Citation: Sack J, Najafian N, DeLisle A, Jakab S. Being accompanied to liver discharge clinic: An easy measure to identify potential liver transplant candidates among those previously considered ineligible. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(4): 370-378

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i4/370.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i4.370

The limited supply of donor livers necessitates careful selection of potential liver transplant candidates by institutional transplant recipient review committees. Each institution has different criteria for listing patients with cirrhosis based on medical, social, and economic factors, some of which remain controversial[1-3]. Patients considered to be unsuitable candidates for liver transplantation are often followed by their providers with the hope of candidacy reassessment once they fulfill the appropriate medical and psychosocial criteria. There is limited literature on specific strategies to achieve liver transplant eligibility for patients with cirrhosis who are initially declined.

Few studies have looked at causes of liver transplant ineligibility among patients with cirrhosis. A single center study found that after initial transplant referral, patients were often declined because they were too well, had co-existing medical contraindications, or needed addiction rehabilitation[4]. Another study found that patients who were declined for non-medical reasons often did not meet the minimum alcohol abstinence requirements and lacked social support[5]. These barriers to liver transplantation are often challenging to overcome, and it can be difficult to determine which patients would be able to achieve the changes needed to become suitable candidates.

Identifying and addressing psychosocial issues early among potential liver transplant candidates with cirrhosis is important. Alcohol relapse after liver transplantation has been associated with mental health issues, lack of a stable life partner, or less than six months of sobriety[6,7]. Additionally, a survey assessing the role of psychosocial evaluations on liver transplant candidacy found that transplant psychosocial evaluators assigned greater importance to coping skills and the ability to adapt to stress, and were less likely to recommend transplant listing for those with poor social support[8]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that psychological characteristics could be used to identify patients less likely to be suitable liver transplant candidates, allowing for targeted support and engagement to improve chances for transplant eligibility[9].

These observations underscore the importance of identifying patients’ support networks and psychosocial barriers early. As these issues are major reasons for liver transplant ineligibility among those who might otherwise be suitable candidates, an early intervention could potentially improve liver transplant candidacy. Unfortunately, there are no specific strategies for achieving liver transplant eligibility among those considered unsuitable. We aimed to identify clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with future liver transplant eligibility among patients seen at a transitional care liver clinic (TCLC) who were considered transplant ineligible but without absolute contraindications.

This is a retrospective study of discharged patients whose first TCLC visits were scheduled between March 2015 and December 2015, with follow up through December 2016 at a single tertiary academic center. Patients were included if they had cirrhosis, were not considered liver transplant candidates, were discharged from the liver inpatient service, were alive but not hospitalized at the first scheduled TCLC appointment, and were not seen by an outpatient hepatologist or gastroenterologist at another institution. Patients were excluded if they had received a liver transplant previously or within 90 days of the hospital discharge prior to the first TCLC visit, if they were on hospice within 90 days of that discharge, if they were older than 70 years, or if they had an irreversible contraindication to liver transplantation. Transplant listing was assessed 1 year after the first scheduled TCLC encounter. Charts were reviewed for demographics, clinical data, previous liver care, show rate at first TCLC visit, whether they were accompanied by family or friends during the first TCLC visit (being accompanied was not asked or required), and liver transplant listing at 1 year. Yale University Institutional Review Board approval was obtained.

Statistical analyses were performed using student's t-test for numerical data and chi-square test for categorical data. The statistical software package SPSS for Windows (SPSS Inc, version 25) was used to analyze the data, and P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference.

Eighty-six patients met the inclusion criteria and were scheduled in TCLC. Seventeen patients were excluded given the very low probability of transplant candidacy at age 70 or older, 6 patients were excluded for untreatable malignancies, and 4 patients were excluded for extensive comorbidities that indefinitely precluded transplantation, leaving a total of 69 eligible patients, Figure 1.

The majority of patients were unmarried Caucasian men with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis, and with mean Model of End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score of 15, Table 1. Forty-six patients (66.7%) showed to the first scheduled post-discharge TCLC appointment. Mean time from hospital discharge to first TCLC appointment was 9.7 days (range 3-29 d) as compared to 8.2 days (range 4-24 d) for those that did not show. The patients who showed were not transplant candidates because of active alcohol use (63.0%), lack of social support (17.4%), active substance use (10.9%), low MELD (4.3%), and poor medical optimization (4.3%). The patients who did not show to the scheduled TCLC visit were alive and not hospitalized at the time of the scheduled appointment, and were not transplant candidates because of active alcohol use (56.5%), lack of social support (21.7%), low MELD (13.0%), and active substance use (8.7%). There was no statistical difference between those that showed and those that did not show based on demographics, recent alcohol or substance use, cirrhosis etiology, cirrhosis decompensations, Child-Pugh score (CPS), MELD, or prior hepatology care, Table 2.

| Variables | Included patients[n = 69] |

| Age | |

| Mean (range) | 51.4 (26-69) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 45 (65.2%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 44 (63.8%) |

| Hispanic | 12 (17.4%) |

| African American | 11 (15.9%) |

| Other | 2 (2.9%) |

| Insurance | |

| Medicaid | 38 (55.1%) |

| Medicare | 13 (18.8%) |

| Private | 14 (20.3%) |

| Uninsured | 4 (5.8%) |

| Homeless | 2 (2.9%) |

| English primary language | 63 (91.3%) |

| Marital Status | |

| Married | 27 (39.1%) |

| Single | 42 (60.9%) |

| Cirrhosis etiology | |

| EtOH | 39 (56.5%) |

| EtOH/HCV | 15 (21.7%) |

| HCV | 7 (10.1%) |

| NASH | 4 (5.8%) |

| PBC | 1 (1.4%) |

| NASH/EtOH | 1 (1.4%) |

| AIH | 1 (1.4%) |

| HBV | 1 (1.4%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Decompensation | 63 (91.3%) |

| Ascites | 54 (78.3%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 38 (55.1%) |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 20 (29.0%) |

| Child Pugh Score | |

| A | 9 (13.0%) |

| B | 34 (49.3%) |

| C | 26 (37.7%) |

| MELD mean (range) | 15.0 (6-30) |

| Patient reported active alcohol use on last admission | 40 (58.0%) |

| Patient reported active substance use on last admission | 9 (13.0%) |

| Previous 1 yr hospitalizations | 44 (63.8%) |

| Previous 1 yr hepatology visit | 25 (36.2%) |

| Accompanied at first TCLC | 19 (27.5%) |

| Deceased at 1 yr | 20 (29.0%) |

| Variables | Show patients[n = 46] | No Show patients[n = 23] | P value |

| Age | |||

| Mean (range) | 51.8 (26-69) | 50.6 (30-68) | 0.63 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 31 (67.4%) | 14 (60.9%) | 0.59 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 32 (69.6%) | 12 (52.2%) | 0.16 |

| Hispanic | 6 (13.0%) | 6 (26.1%) | 0.18 |

| African American | 6 (13.0%) | 5 (21.7%) | 0.35 |

| Other | 2 (4.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0.55 |

| Insurance | |||

| Medicaid | 22 (47.8%) | 16 (69.6%) | 0.09 |

| Medicare | 10 (21.7%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.38 |

| Private | 11 (23.9%) | 3 (13.0%) | 0.29 |

| Uninsured | 3 (6.5%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.72 |

| Homeless | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.61 |

| English primary language | 43 (93.5%) | 20 (87.0%) | 0.36 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 19 (41.3%) | 8 (34.8%) | 0.60 |

| Single | 27 (58.7%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.60 |

| Cirrhosis etiology | |||

| EtOH | 28 (60.9%) | 11 (47.8%) | 0.30 |

| EtOH/HCV | 11 (23.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.54 |

| HCV | 3 (6.5%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.16 |

| NASH | 2 (4.3%) | 2 (8.9%) | 0.47 |

| PBC | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| NASH/EtOH | 1 (2.2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| AIH | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.33 |

| HBV | 0 (0%) | 1 (4.3%) | 0.33 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| Decompensation | 43 (93.5%) | 20 (87.0%) | 0.36 |

| Ascites | 36 (78.2%) | 18 (78.3%) | 1 |

| Hepatic Encephalopathy | 27 (58.7%) | 11 (47.8%) | 0.39 |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 13 (28.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 0.85 |

| Child Pugh Score | |||

| A | 5 (10.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.45 |

| B | 24 (52.2%) | 10 (43.5%) | 0.50 |

| C | 17 (37.0%) | 9 (39.1%) | 0.86 |

| MELD mean (range) | 15.3 (6–30) | 14.4 (7-26) | 0.54 |

| Patient reported active alcohol use on last admission | 27 (58.7%) | 13 (56.5%) | 0.86 |

| Patient reported active substance use on last admission | 5 (10.9%) | 4 (17.4%) | 0.45 |

| Previous 1 yr hospitalizations | 29 (63.0%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0.86 |

| Previous 1 yr hepatology visit | 16 (34.8%) | 9 (39.1%) | 0.72 |

| Accompanied at first TCLC | 19 (41.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.0001 |

| Deceased at 1 yr | 13 (28.3%) | 7 (30.4%) | 0.85 |

Seven of the 46 patients that showed to the first scheduled TCLC appointment became liver transplant candidates at 1 year while none of the 23 patients that no-showed did. (15.2% vs 0.0%, P = 0.08). These 7 patients were initially not transplant eligible because of active alcohol use (57.1 %), active substance use (14.3%), lack of social support (14.3%), and need for medical optimization (14.3%).

Among the patients who showed to the first TCLC visit, 7 patients became transplant eligible at 1 year and 39 did not. The only statistically significant finding between these two groups was the presence of a family member or friend to TCLC visit (this was not asked or required). Six of the 7 patients who became transplant eligible and 13 of the 39 patients who did not become transplant eligible had been accompanied at the first TCLC appointment (85.7% vs 33.3%, P = 0.01). Though not statistically significant, those that became transplant eligible at 1 year had a trend for having alcoholic cirrhosis and for being Caucasian. Those who did not become transplant eligible at 1 year had a trend for recent active alcohol use and for having Medicaid insurance. There were no statistical differences based on demographics, cirrhosis etiology, CPS, MELD, or prior hepatology care, Table 3.

| Variables | Show patients, | Show patients, | P value |

| transplant eligible 1 yr | non-transplant eligible 1 yr | ||

| [n = 7] | [n = 39] | ||

| Age | |||

| Mean (range) | 51.9 (26-69) | 51.8 (34-69) | 0.98 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 5 (71.4%) | 26 (66.7%) | 0.80 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||

| Caucasian | 7 (100.0%) | 25 (64.1%) | 0.08 |

| Hispanic | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (15.4%) | 0.57 |

| African American | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (15.4%) | 0.57 |

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.1%) | 1 |

| Insurance | |||

| Medicaid | 1 (14.3%) | 18 (46.2%) | 0.11 |

| Medicare | 2 (28.6%) | 9 (23.1%) | 0.75 |

| Private | 3 (42.9%) | 9 (23.1%) | 0.27 |

| Uninsured | 1 (14.3%) | 3 (7.7%) | 0.57 |

| Homeless | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 |

| English Primary Language | 7 (100.0%) | 36 (92.3%) | 1 |

| Marital Status | |||

| Married | 3 (42.9%) | 16 (41.0%) | 0.93 |

| Single | 4 (57.1%) | 23 (59.0%) | 0.93 |

| Cirrhosis Etiology | |||

| EtOH | 6 (85.7%) | 22 (56.4%) | 0.14 |

| EtOH/HCV | 0 (0.0%) | 11 (28.2%) | 0.17 |

| HCV | 1 (14.3%) | 2 (5.1%) | 0.37 |

| NASH | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (5.1%) | 1 |

| PBC | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 |

| NASH/EtOH | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (2.6%) | 1 |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| Decompensation | 7 (100.0%) | 36 (92.3%) | 1 |

| Ascites | 6 (85.7%) | 30 (76.9%) | 0.60 |

| Hepatic Encephalopathy | 4 (57.1%) | 23 (59.0%) | 0.93 |

| Variceal hemorrhage | 1 (14.3%) | 12 (27.3%) | 0.79 |

| Child Pugh Score | |||

| A | 1 (14.1%) | 4 (10.3%) | 0.75 |

| B | 5 (71.4%) | 19 (48.7%) | 0.27 |

| C | 1 (14.1%) | 16 (41.0%) | 0.18 |

| MELD mean (range) | 13.7 (10-20) | 15.6 (6-30) | 0.44 |

| Patient reported active alcohol use on last admission | 2 (28.6%) | 25 (64.1%) | 0.08 |

| Patient reported active substance use on last admission | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (12.8%) | 1 |

| Previous 1 yr hospitalizations | 5 (71.4%) | 24 (61.5%) | 0.62 |

| Previous 1 yr hepatology visit | 3 (42.9%) | 13 (33.3%) | 0.63 |

| Accompanied at first TCLC | 6 (85.7%) | 13 (33.3%) | 0.01 |

| Deceased at 1 yr | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (33.3%) | 0.17 |

There is limited literature on strategies to optimize liver transplant candidacy for patients considered ineligible. At our institution, about 30% of referred patients are ultimately accepted as liver transplant candidates. Transplant eligibility requires an adequate support system, among other medical and psychosocial criteria.

This study followed non-transplant eligible patients seen at their post discharge TCLC visit to identify which patients would become transplant candidates at 1 year. We found that patients who showed to the first TCLC visit had a trend for increased liver transplant eligibility at 1 year. Being accompanied by family or friends during the first TCLC visit was correlated with an even higher rate of liver transplant candidacy at 1 year. Of note, patients were not required or asked to bring family or friends to the TCLC encounter.

These observations suggest that patient and family involvement in the immediate post-hospitalization period may predict future liver transplant eligibility for patients previously considered unsuitable but did not have absolute contraindications. All 7 patients who became liver transplant candidates at 1 year had shown to the initial TCLC appointment. 6 of those 7 had been accompanied by a family member or friend. After review of demographics and clinical history, being accompanied at the first TCLC visit was the only statistically significant difference between the 7 patients that showed to TCLC and became transplant candidates at 1 year, and the 39 patients that showed to TCLC but did not become transplant candidates at 1 year. Though there was a trend for more Medicaid insurance and recent active alcohol use for those that showed and did not became transplant candidates at 1 year, both patient populations consisted mostly of unmarried men with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis and active alcohol use. Moreover, both patient groups had been previously declined liver transplant candidacy because of active alcohol use and poor social support. These findings reinforce the importance of continued liver care for transplant ineligible patients because the window for transplant candidacy can re-open, even among patients with challenging psychosocial situations.

The observed correlation of transplant eligibility at 1 year with being accompanied by family or friends at the first transitional liver care clinic is significant and should be explored further in future studies. We do not suggest that having someone come with a patient to clinic is sufficient for transplant eligibility, but rather consider it a potential marker of the support available at home, which is especially important for transplant centers such as ours that require a strong support system. Involvement of family and caregivers at a visit may help them understand the patient’s liver disease as well as the barriers that preclude transplantation, allowing for better care of their loved ones at home. Many of these patients with decompensated cirrhosis and psychosocial issues likely face challenges caring for themselves and fully understanding all content discussed at a liver clinic visit - over half of our study patients had hepatic encephalopathy and were single. It is also plausible that follow up in TCLC with family members who know the patient enabled physicians to identify and provide appropriate resources for addressing specific psychosocial issues. More research is needed to identify and to support patients deemed ineligible for liver transplantation because of psychosocial reasons, with the hope of achieving transplant eligibility.

The limitations of this study are that it is retrospective with a small sample size at a single tertiary academic center. However, the patients in all groups had similar characteristics and were evaluated at a single liver transplant center which allowed for consistency in the assessment of transplant eligibility. An advantage of our study was that it included a high-risk population consisting of predominantly unmarried men with decompensated alcoholic cirrhosis who had been mostly declined for active alcohol and substance use as well poor social support. Six of the 7 patients who became transplant eligible at 1 year had one of these significant barriers.

While these findings suggest that patient and family engagement after hospital discharge may predict future liver transplant eligibility for those initially considered unsuitable, we should continue to advocate for liver transplant evaluations for all patients provided that there are no absolute contraindications.

There is minimal data on the long-term outcomes of patients with cirrhosis who are declined for liver transplantation. Many of these ineligible patients are followed by general hepatology and gastroenterology providers with the hope of re-eligibility for transplantation. Specific strategies to achieve liver transplant eligibility for these patients have not been studied.

We were motivated to pursue this project so that the field may have a better understanding of the clinical and sociodemographic factors that may predict future liver transplant eligibility for those initially considered ineligible.

The objective of our study was to assess clinical and sociodemographic factors associated with one-year liver transplant eligibility among patients with cirrhosis seen in a transitional care liver clinic who were considered unsuitable transplant candidates but did not have absolute contraindications.

Retrospective, single-center study.

69 patients were identified, predominantly Caucasian men with alcoholic cirrhosis. 46 patients (67%) presented to the first TCLC visit. Seven of 46 patients that presented to the first TCLC visit became transplant candidates at one year, while 0 of 23 patients that no-showed did (15.2% vs 0%, P = 0.08). Six of 7 patients who showed and became transplant eligible were accompanied by family or friends at the first TCLC appointment, compared to 13 of 39 patients who showed and did not become transplant eligible (85.7% vs 33.3%, P = 0.01).

Patients ineligible for liver transplantation, but without absolute contraindications, who presented to our TCLC were more likely to be listed for liver transplantation at one year if they were joined by family or friends at the first clinic visit. While more research is needed, patient and family participation in clinical care may serve as a surrogate marker of social support for patients previously declined for liver transplant.

This study reinforced the importance of investigating the long-term outcomes of patients with cirrhosis who are declined for liver transplantation. Given our small study population and known variations in transplant listing policies at each institution, larger multi-centered prospective studies are needed.

We would like to thank Michael Schilsky MD, David Mulligan MD, and Yale New Haven Transplant Center team for providing data regarding liver transplant referrals and acceptance rate.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hilmi I, Tzamaloukas AHH S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Zhang YL

| 1. | Secunda K, Gordon EJ, Sohn MW, Shinkunas LA, Kaldjian LC, Voigt MD, Levitsky J. National survey of provider opinions on controversial characteristics of liver transplant candidates. Liver Transpl. 2013;19:395-403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fleming JN, Lai JC, Te HS, Said A, Spengler EK, Rogal SS. Opioid and opioid substitution therapy in liver transplant candidates: A survey of center policies and practices. Clin Transplant. 2017;31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Spengler EK, O'Leary JG, Te HS, Rogal S, Pillai AA, Al-Osaimi A, Desai A, Fleming JN, Ganger D, Seetharam A, Tsoulfas G, Montenovo M, Lai JC. Liver Transplantation in the Obese Cirrhotic Patient. Transplantation. 2017;101:2288-2296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Arya A, Hernandez-Alejandro R, Marotta P, Uhanova J, Chandok N. Recipient ineligibility after liver transplantation assessment: a single centre experience. Can J Surg. 2013;56:E39-E43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Alali J, Ramji A, Ho JK, Scudamore CH, Erb SR, Cheung E, Kopit B, Bannon CA, Chung SW, Soos JG, Buczkowski AK, Brooks EM, Steinbrecher UP, Yoshida EM. Liver transplant candidacy unsuitability: a review of the British Columbia experience. Can J Gastroenterol. 2006;20:95-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | De Gottardi A, Spahr L, Gelez P, Morard I, Mentha G, Guillaud O, Majno P, Morel P, Hadengue A, Paliard P, Scoazec JY, Boillot O, Giostra E, Dumortier J. A simple score for predicting alcohol relapse after liver transplantation: results from 387 patients over 15 years. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1183-1188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kelly M, Chick J, Gribble R, Gleeson M, Holton M, Winstanley J, McCaughan GW, Haber PS. Predictors of relapse to harmful alcohol after orthotopic liver transplantation. Alcohol Alcohol. 2006;41:278-283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Flamme NE, Terry CL, Helft PR. The influence of psychosocial evaluation on candidacy for liver transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2008;18:89-96. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Harper RG, Wager J, Chacko RC. Psychosocial factors in noncompliance during liver transplant selection. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2010;17:71-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |