Published online Oct 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i10.719

Peer-review started: July 24, 2019

First decision: August 7, 2019

Revised: August 20, 2019

Accepted: October 2, 2019

Article in press: October 2, 2019

Published online: October 27, 2019

Processing time: 94 Days and 19.7 Hours

Depression is a growing public health problem that affects over 350 million people globally and accounts for approximately 7.5% of healthy years lost due to disability. Escitalopram, one of the first-line medications for the treatment of depression, is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor and one of the most commonly prescribed antidepressant medications worldwide. Although thought to be generally safe and with minimal drug-drug interactions, we herein present an unusual case of cholestatic liver injury, likely secondary to escitalopram initiation.

A 56-year-old Chinese lady presented with fever and cholestatic liver injury two weeks after initiation of escitalopram for the treatment of psychotic depression. Physical examination was unremarkable. Further investigations, including a computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis and tests for hepatitis A, B and C and for autoimmune liver disease were unyielding. Hence, a diagnosis of escitalopram-induced liver injury was made. Upon stopping escitalopram, repeat liver function tests showed downtrending liver enzymes with eventual normalization of serum aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase one-week post-discharge.

Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of escitalopram-induced liver injury when initiating depressed patients on antidepressant treatment. This requires extra vigilance as most patients may remain asymptomatic. Measurement of liver function tests could be considered after initiation of antidepressant treatment, especially in patients with pre-existing liver disease.

Core tip: We herein report a probable case of escitalopram-induced liver injury. A 56-year-old Chinese lady presented with fever and cholestatic liver injury two weeks after initiation of escitalopram for the treatment of psychotic depression. Physical examination and investigations for stones, viral hepatitis and autoimmune liver disease were unyielding. Upon stopping escitalopram, repeat liver function tests showed downtrending liver enzymes with eventual normalization of serum aminotransferase levels. Clinicians should be aware of the possibility of drug-induced liver injury associated with escitalopram use, when initiating depressed patients on antidepressant treatment. This requires extra vigilance as most patients may remain asymptomatic.

- Citation: Ng QX, Yong CSK, Loke W, Yeo WS, Soh AYS. Escitalopram-induced liver injury: A case report and review of literature. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(10): 719-724

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i10/719.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i10.719

Depression is a growing public health problem that affects over 350 million people globally and accounts for approximately 7.5% of healthy years lost due to disability[1]. Escitalopram is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and one of the most commonly prescribed antidepressant medications worldwide[2]. Although thought to be generally safe and with minimal drug-drug interactions[3], we herein present an unusual case of cholestatic liver injury, likely secondary to escitalopram initiation.

This patient was a 56-year-old Chinese lady transferred to our hospital for fever and deranged liver enzymes for investigation. She was receiving treatment at a psychiatric hospital for psychotic depression prior. At presentation, she was asymptomatic and did not have any localizing signs of infection. She had no cough, sore throat, rhinorrhea, diarrhea or dysuria. There was no change in the colour of her urine or stools. She had no constitutional symptoms or significant weight loss over the past 6 mo, and no chills, rigors or night sweats throughout. She did not consume any raw foods or herbal supplements and had not travelled outside of Singapore in the recent years. Her past medical history was significant for psychotic depression, for which she was being managed with escitalopram 5 mg once daily and olanzapine 7.5 mg twice daily. She had started escitalopram and olanzapine two weeks prior to presentation. She had no known drug allergies.

On physical examination, she had an average build (body mass index 22.8 kg/m2), was not jaundiced, had no rash present, and did not have any tattoos or needle track marks. On palpation, her abdomen was soft and non-tender, and there were no palpable masses or organomegaly. Physical examination was unremarkable. There was no palpable cervical, axillary, supraclavicular, or inguinal lymph nodes.

Laboratory studies revealed a normochromic, normocytic anemia (as confirmed on a peripheral blood film) with a haemoglobin level of 10.1 g/dL. Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and haptoglobin were within normal limits. Total whites were not raised at 5.4 × 109 cells/L and eosinophils count were within normal limits as well (0.33 × 109 cells/L). The C-reactive protein was elevated at 67.5 mg/L, erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 10 mm/h and two sets of peripheral aerobic and anaerobic blood cultures showed no bacterial growth after 72 h. Her thyroid function test (TSH and free T4), serum electrolytes, urea and creatinine were all within normal limits, while her liver panel showed raised alanine aminotransferase (ALT, 183 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (AST, 99 U/L), alkaline phosphatase (ALP, 552 U/L) and GGT (510 U/L).

A hepatitis screen was done, which found that antibodies against hepatitis C virus were non-reactive, the surface antigen of the hepatitis B virus was non-reactive as well and anti-HBs was >1000 IU/L. This indicated recovery from (and immunity to) the hepatitis B virus (HBV) or successful immunization with HBV vaccine. She had received Hepatitis A and B vaccinations as a young adult.

Serum autoantibodies were performed and included antinuclear antibody of <1:640, speckled pattern, negative anti-smooth muscle antibody titre, and negative antimitochondrial M2 antibody.

In terms of imaging, a computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis found no pancreatic or other mass. Hepatic parenchymal attenuation was normal, with no focal lesions noted. There were no radio-opaque gallstones or biliary dilatation.

Given the history, examination and investigation findings, a diagnosis of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) was made.

Although olanzapine has also been linked to reports of DILI[4], it was precluded as a culprit drug in this case because the patient had previously taken it with no issues. She was treated with oral olanzapine 10 mg nightly and oral fluoxetine 20 mg every morning in February 2018 for psychotic depression, with good resolution of symptoms and the drugs were subsequently tapered and stopped by December 2018.

The Roussel Uclaf Causality Assessment Method (RUCAM) scoring[5] also helps clinicians determine how likely the diagnosis of DILI is. The components considered are: (1) time to onset (+1 or +2); (2) course (-2, 0, +1, +2 or +3); (3) risk factors (2 scores: 0 or +1 each); (4) concomitant drugs (0, -1, -2 or -3); (5) nondrug causes of liver injury (-3, -2, 0, +1, or +2); (6) previous information on the hepatotoxicity of the drug (0, +1, or +2); and (7) response to rechallenge (-2, 0, +1, or +3)[5]. Applying the RUCAM scoring to our patient, escitalopram yielded a total score of at least 5, suggesting that it was a ‘probable’ cause of DILI.

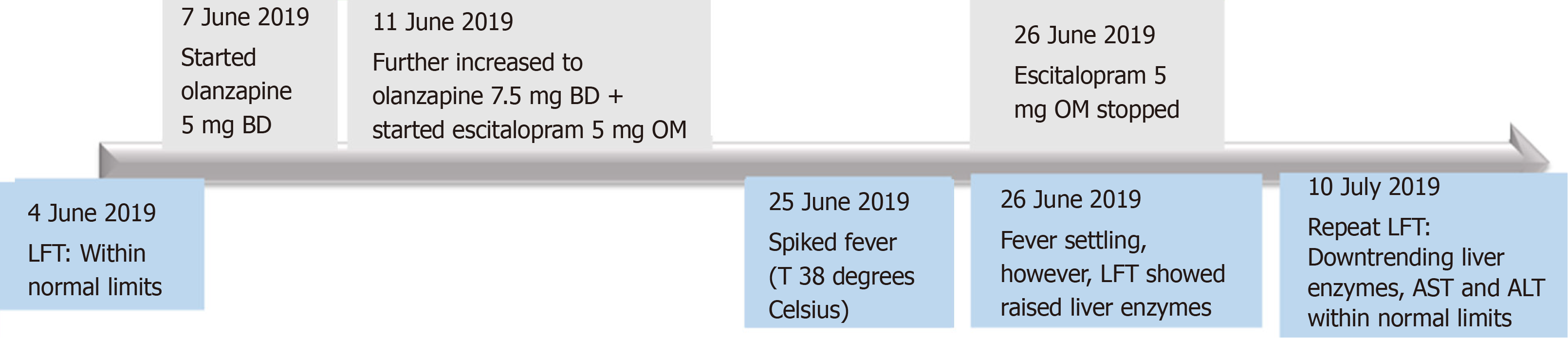

Escitalopram, which was newly initiated, was suspected to be the culprit drug based on the temporal sequence (Figure 1), the fact that it undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism[6] and its overall likelihood of DILI based on RUCAM scoring. Treatment was thus withdrawal of escitalopram.

Our patient had no further temperature spikes while inpatient. Upon stopping escitalopram, repeat liver function tests showed downtrending liver enzymes with eventual normalization of serum AST and ALT one week post-discharge (Table 1). Patient remained well and asymptomatic.

| Test | 4 June 2019 | 26 June 2019 | 27 June 2019 | 10 July 2019 | 24 July 2019 |

| Albumin (g/L) | 35 | 35 | 34 | 39 | 36 |

| AST (U/L) | 28 | 99 | 67 | 27 | 22 |

| ALT (U/L) | 32 | 183 | 150 | 30 | 22 |

| GGT (U/L) | 25 | 510 | 495 | 275 | 144 |

| ALP (U/L) | 102 | 552 | 585 | 237 | 123 |

| Bilirubin, total (µmol/L) | 17 | 24 | 11 | 12 | 7 |

| Protein, total (g/L) | 69 | 72 | 74 | 78 | 69 |

| Globulin (g/L) | 35 | 38 | 40 | 39 | 33 |

Drug-induced liver injury (DILI) is one of the leading causes of hepatic failure in the Western world[7]. It is often a difficult diagnosis to make as it relies largely on the exclusion of other potential causes[8]. A detailed drug chart in relation to the timing of onset of liver injury and recovery after the implicated agent is stopped can help clinch the diagnosis. In this patient, as she presented with fever and deranged liver enzymes, it was vital to consider gallstone disease, viral hepatitis, or autoimmune liver disease. CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis and tests for hepatitis A, B and C and for autoimmune liver disease were negative.

While a liver biopsy is not always indicated, in DILI, liver biopsy shows only non-specific findings, none of the features are pathognomonic. However, liver biopsy may help in cases where there is ambiguity and other causes (e.g., autoimmune liver disease or hepatitis flare) are possible differentials. RUCAM scoring also helps clinicians determine how likely the diagnosis of DILI is.

Depending on the pattern of hepatic injury, DILI can be classified as hepatocellular, cholestatic, or mixed[9]. Hepatocellular injury is marked by elevated serum ALT with a small or no increase in ALP levels; an associated high serum bilirubin level, found in cases of severe hepatocellular damage, connotes poor prognosis[9]. While cholestatic liver injury, as in the case of our patient, is characterized by markedly elevated serum ALP and only slightly higher than normal ALT levels. In cases of mixed injury, both ALT and ALP levels are elevated.

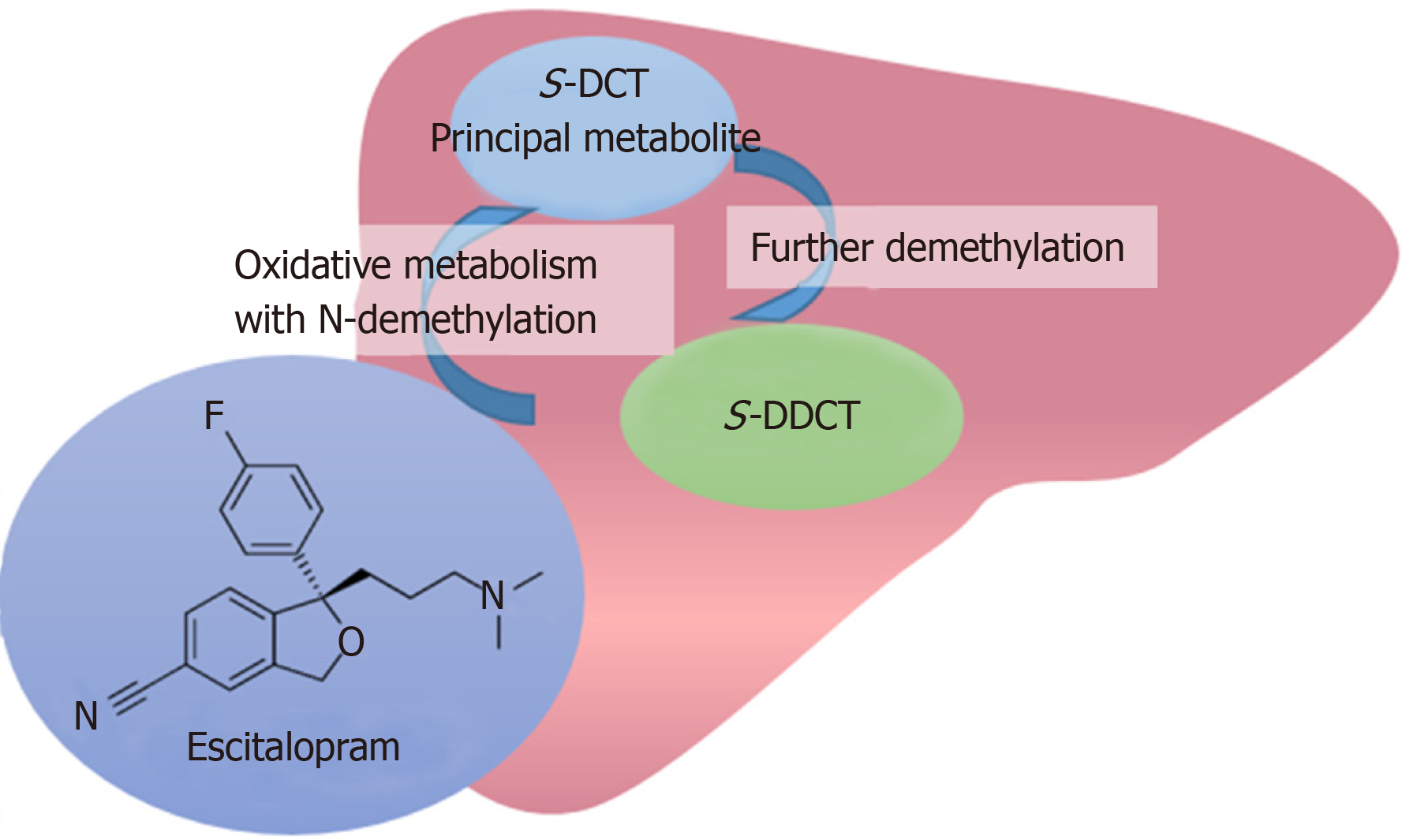

With regard to the pathophysiology of DILI, it is thought to be due to direct, indirect or idiosyncratic hepatotoxicity[8]. In the case of escitalopram, it is extensively metabolized by the liver, mainly via the cytochrome P450 system (CYP3A4, CYP2C19 and, to a lesser extent, CYP2D6)[3] and hepatotoxicity may be due to toxic intermediates (Figure 2). In literature, there is only one published case report of a 30 year-old woman who developed cholestatic liver injury[10], marked by jaundice and pruritus 2 mo after starting citalopram (citalopram is a racemic mixture, while escitalopram is the therapeutically active S-enantiomer). Citalopram was dosed at 10 mg daily for 1 month, followed by 20 mg daily. Similar to our patient, she had previously tried fluoxetine (another SSRI antidepressant) with no issues.

In the case of our patient, we are unable to entirely exclude the fact that olanzapine may have also contributed to her liver injury as olanzapine also undergoes extensive hepatic metabolism by CYP1A2 and to a lesser extent by CYP2D6[11]. Olanzapine has also been reported to cause transient serum liver enzyme elevations[4].

According to the results of a multicenter drug surveillance program of 184234 psychiatric inpatients treated with antidepressants between 1993 and 2011 in 80 psychiatric hospitals, 149 cases of DILI (0.08%) were reported[12]. However, the risk of antidepressant-induced liver injury is likely underestimated as most patients are asymptomatic, especially during early stages of DILI.

DILI is thought to be dose-independent, albeit there could be some dose-dependent aspects as DILI tended to occur at high median dosages[12]. In terms of choice of psychotropic medication, theoretically speaking, drugs that are not metabolized extensively and primarily renally excreted are probably the safest in patients with pre-existing liver disease. These drugs include paliperidone[13], sulpiride[14] and amisulpride[15].

Although thought to be generally safe and with minimal drug-drug interactions, clinicians should be aware of the possibility of escitalopram-induced liver injury when initiating depressed patients on antidepressant treatment. This requires extra vigilance as most patients may remain asymptomatic. It is still controversial whether routine monitoring is recommended, especially in patients with pre-existing liver disease. Fortunately, DILI is typically reversible after withdrawal of the implicated drug and patients should have a favourable outcome.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: Singapore

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Khoury T, Yeoh SW, Zapater P S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

| 1. | Lépine JP, Briley M. The increasing burden of depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:3-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 439] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Grover S, Avasth A, Kalita K, Dalal PK, Rao GP, Chadda RK, Lakdawala B, Bang G, Chakraborty K, Kumar S, Singh PK, Kathuria P, Thirunavukarasu M, Sharma PS, Harish T, Shah N, Deka K. IPS multicentric study: Antidepressant prescription patterns. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:41-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | von Moltke LL, Greenblatt DJ, Giancarlo GM, Granda BW, Harmatz JS, Shader RI. Escitalopram (S-citalopram) and its metabolites in vitro: cytochromes mediating biotransformation, inhibitory effects, and comparison to R-citalopram. Drug Metab Dispos. 2001;29:1102-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Domínguez-Jiménez JL, Puente-Gutiérrez JJ, Pelado-García EM, Cuesta-Cubillas D, García-Moreno AM. Liver toxicity due to olanzapine. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2012;104:617-618. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Danan G, Benichou C. Causality assessment of adverse reactions to drugs--I. A novel method based on the conclusions of international consensus meetings: application to drug-induced liver injuries. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46:1323-1330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1015] [Cited by in RCA: 1068] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rao N. The clinical pharmacokinetics of escitalopram. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2007;46:281-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Björnsson ES, Bergmann OM, Björnsson HK, Kvaran RB, Olafsson S. Incidence, presentation, and outcomes in patients with drug-induced liver injury in the general population of Iceland. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1419-1425, 1425.e1-3; quiz e19-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 535] [Cited by in RCA: 581] [Article Influence: 48.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hoofnagle JH, Björnsson ES. Drug-Induced Liver Injury - Types and Phenotypes. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:264-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 375] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aithal GP, Watkins PB, Andrade RJ, Larrey D, Molokhia M, Takikawa H, Hunt CM, Wilke RA, Avigan M, Kaplowitz N, Bjornsson E, Daly AK. Case definition and phenotype standardization in drug-induced liver injury. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:806-815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 589] [Cited by in RCA: 718] [Article Influence: 51.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Milkiewicz P, Chilton AP, Hubscher SG, Elias E. Antidepressant induced cholestasis: hepatocellular redistribution of multidrug resistant protein (MRP2). Gut. 2003;52:300-303. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Callaghan JT, Bergstrom RF, Ptak LR, Beasley CM. Olanzapine. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profile. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:177-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 372] [Cited by in RCA: 379] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Friedrich ME, Akimova E, Huf W, Konstantinidis A, Papageorgiou K, Winkler D, Toto S, Greil W, Grohmann R, Kasper S. Drug-Induced Liver Injury during Antidepressant Treatment: Results of AMSP, a Drug Surveillance Program. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19:pyv126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Vermeir M, Naessens I, Remmerie B, Mannens G, Hendrickx J, Sterkens P, Talluri K, Boom S, Eerdekens M, van Osselaer N, Cleton A. Absorption, metabolism, and excretion of paliperidone, a new monoaminergic antagonist, in humans. Drug Metab Dispos. 2008;36:769-779. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wiesel FA, Alfredsson G, Ehrnebo M, Sedvall G. The pharmacokinetics of intravenous and oral sulpiride in healthy human subjects. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1980;17:385-391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Curran MP, Perry CM. Amisulpride: a review of its use in the management of schizophrenia. Drugs. 2001;61:2123-2150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |