Published online Jan 27, 2019. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.133

Peer-review started: September 18, 2018

First decision: October 18, 2018

Revised: November 4, 2018

Accepted: December 6, 2018

Article in press: December 7, 2018

Published online: January 27, 2019

Processing time: 131 Days and 21.3 Hours

Caval vein thrombosis after hepatectomy is rare, although it increases mortality and morbidity. The evolution of this thrombosis into a septic thrombophlebitis responsible for persistent septicaemia after a hepatectomy has not been reported to date in the literature. We here report the management of a 54-year-old woman operated for a peripheral cholangiocarcinoma who developed a suppurated thrombophlebitis of the vena cava following a hepatectomy.

This patient was operated by left lobectomy extended to segment V with bile duct resection and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. After the surgery, she developed Streptococcus anginosus, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecium bacteraemias, as well as Candida albicans fungemia. A computed tomography scan revealed a bilioma which was percutaneously drained. Despite adequate antibiotic therapy, the patient’s condition remained septic. A diagnosis of septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava was made on post-operative day 25. The patient was then operated again for a surgical thrombectomy and complete caval reconstruction with a parietal peritoneum tube graft. Use of the peritoneum as a vascular graft is an inexpensive technique, it is readily and rapidly available, and it allows caval replacement in a septic area. Septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava after hepatectomy has not been described previously and it warrants being added to the spectrum of potential complications of this procedure.

Septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava was successfully treated with antibiotic and anticoagulation treatments, prompt surgical thrombectomy and caval reconstruction.

Core tip: Caval vein thrombosis after hepatectomy is rare, although it increases mortality and morbidity. Its evolution into a septic thrombophlebitis responsible for persistent septicaemia after a hepatectomy has not been reported to date in the literature. This study reports the management of a 54-year-old woman with peripheral cholangiocarcinoma who developed a suppurated thrombophlebitis of the vena cava following a hepatectomy. A combination of antibiotic and anticoagulation treatments, prompt surgical thrombectomy and complete caval reconstruction was associated with a favorable outcome. Use of the peritoneum as a vascular graft is an inexpensive technique, and it allows caval replacement in a septic area.

- Citation: Maulat C, Lapierre L, Migueres I, Chaufour X, Martin-Blondel G, Muscari F. Caval replacement with parietal peritoneum tube graft for septic thrombophlebitis after hepatectomy: A case report. World J Hepatol 2019; 11(1): 133-137

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v11/i1/133.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v11.i1.133

Caval vein thrombosis after hepatectomy is rare, although it increases mortality and morbidity[1]. The evolution of this thrombosis into a septic thrombophlebitis has not been reported to date in the literature. We here report the management of a 54-year-old woman operated for a peripheral cholangiocarcinoma who developed a suppurated thrombophlebitis of the vena cava following a hepatectomy.

This patient was operated by left lobectomy extended to segment V with bile duct resection and Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy. Besides its cancer, the patient had no medical history, including thromboembolic or cardiovascular diseases. On post-operative day 3 (POD3), she developed Streptococcus anginosus, Escherichia coli, and Enterococcus faecium (E. faecium) bacteraemias, as well as Candida albicans (C. albicans) fungemia. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 5 cm bilioma. Antibiotic treatment based on ceftriaxon, teicoplanin, and caspofungin was started while the bilioma was percutaneously drained on POD10, and cultures were positive for C. albicans. However, both the E. faecium bacteraemia and the C. albicans fungemia persisted, with sepsis (high-grade fever, hyperleukocytosis and tachycardia). The choice and the administration of these antibiotics were deemed to be appropriate, as were the teicoplanin serum levels.

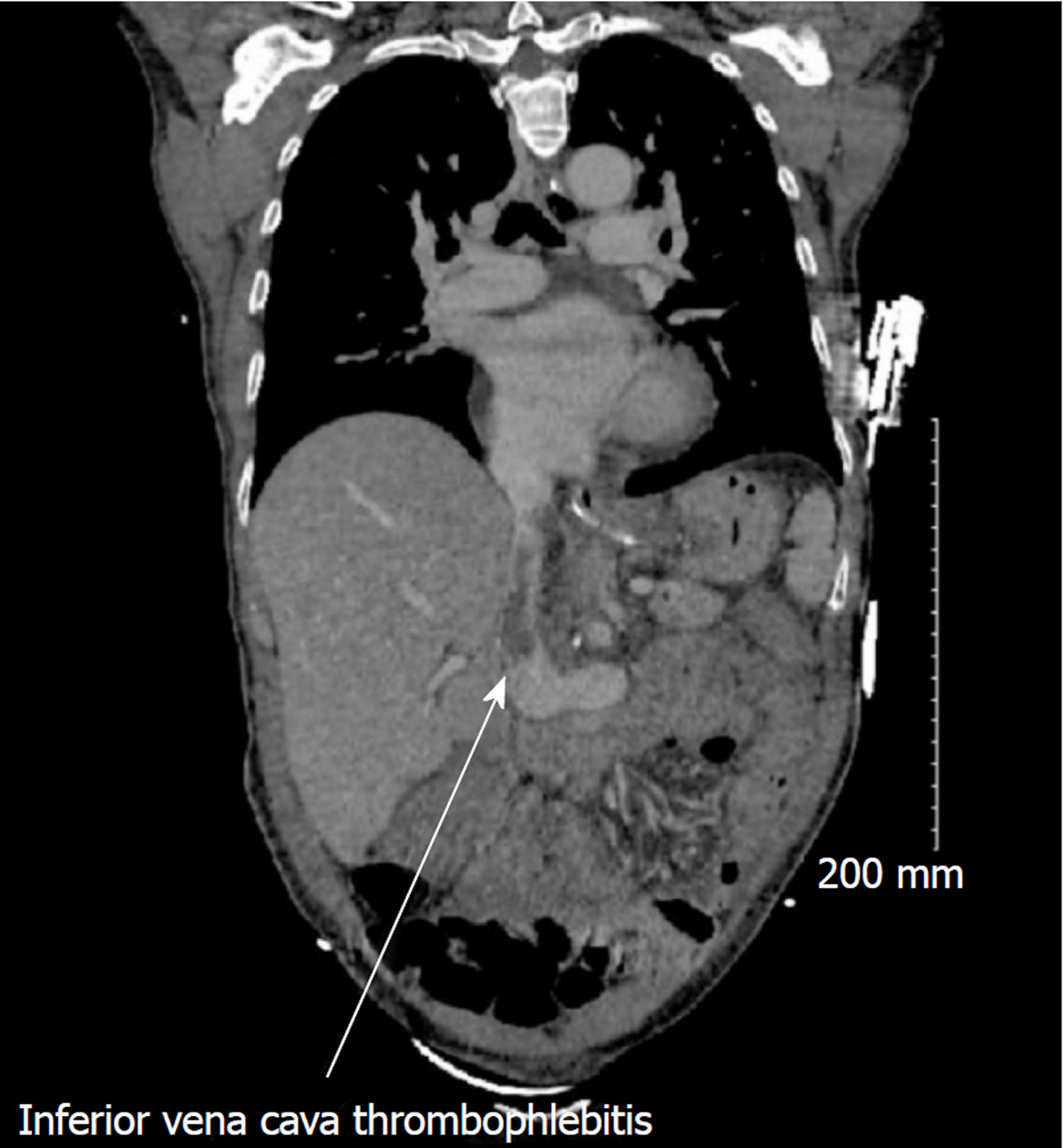

The clinical condition of the patient continued to deteriorate, despite appropriate antibiotic treatment. Another CT scan on POD25 revealed thrombophlebitis of the inferior vena cava closed to the bilioma (Figure 1), and new subpleural nodular lesions suggestive of an embolic mechanism.

A diagnosis of septic thrombophlebitis of the inferior vena cava was made.

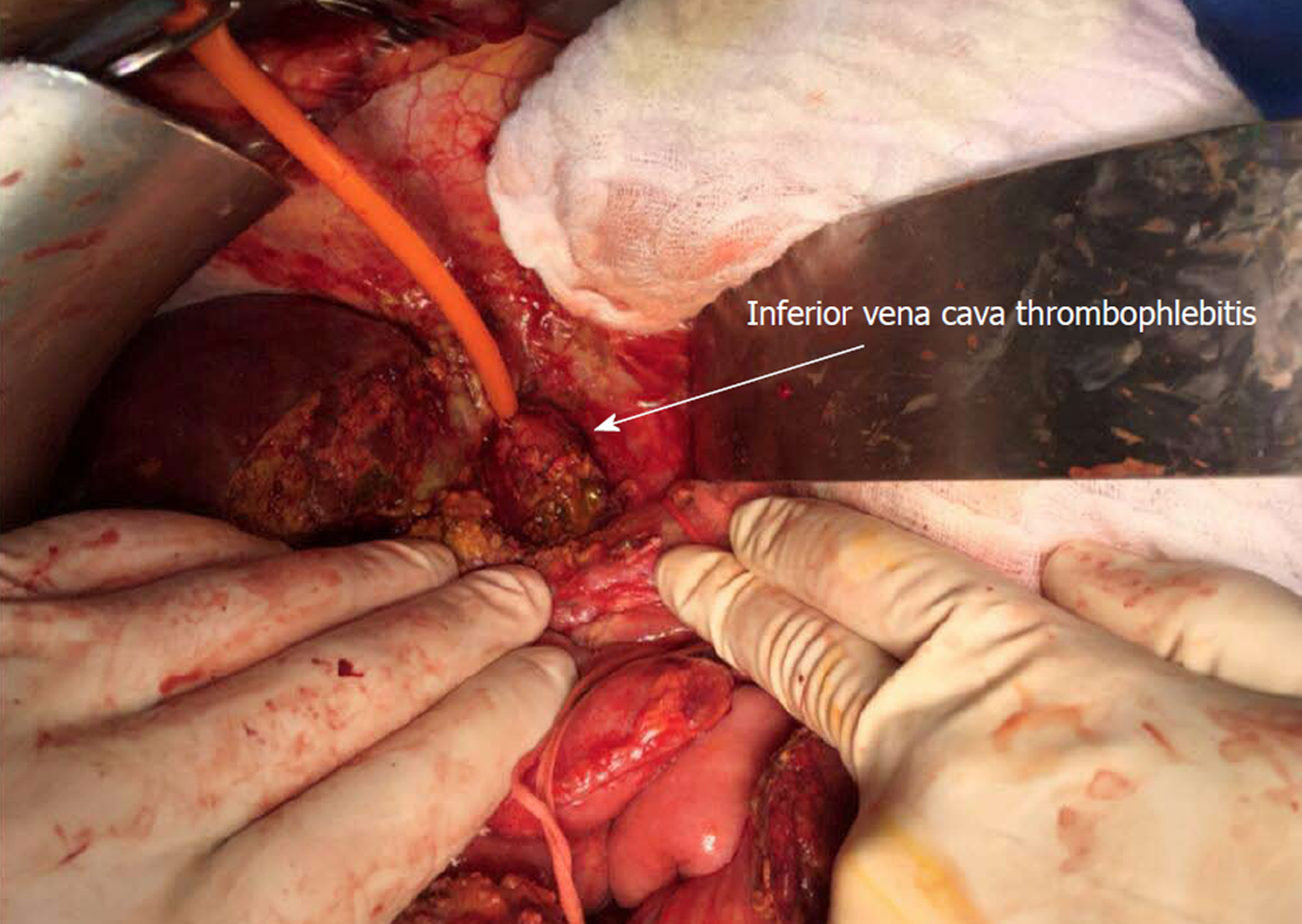

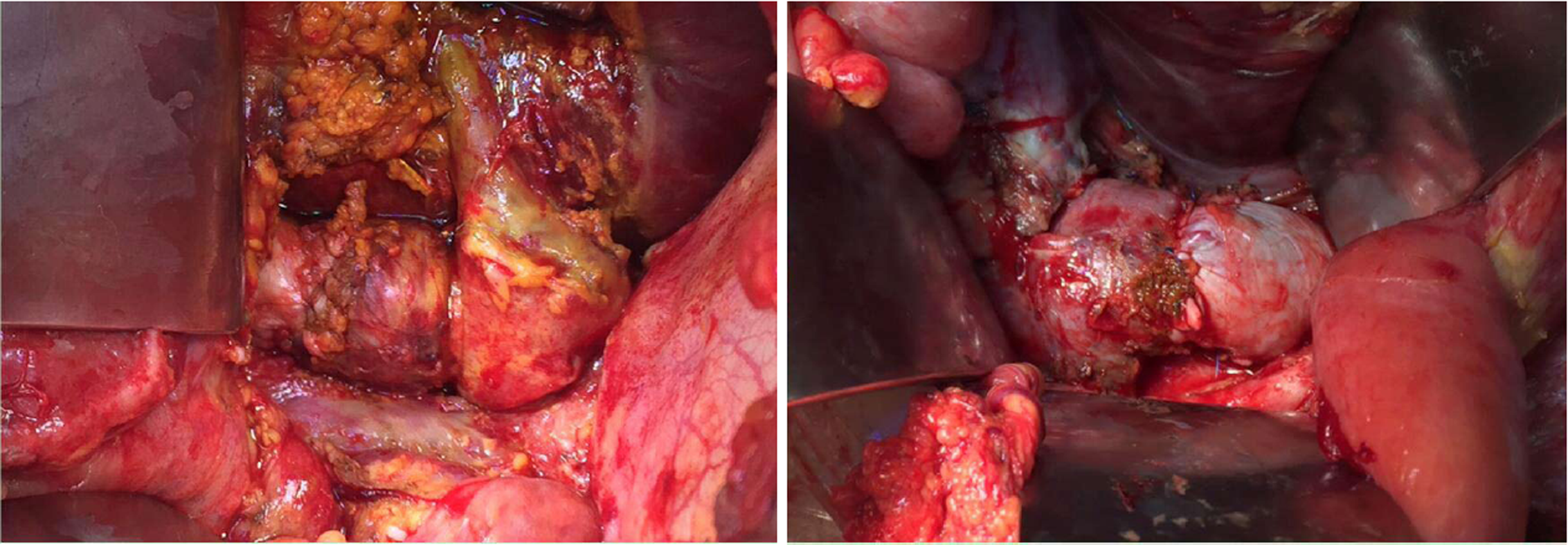

The patient was operated again on POD27 for a thrombectomy and replacement of the inferior vena cava. First, the vena cava was controlled above and below the hepatic vein and the upper the renal veins after performing the Kocher manoeuvre. The bilioma was found along with an infectious necrosis with suppuration and thrombosis of the front side of the vena cava at the rear of the hepatic pedicle (Figure 2). A vascular resection was performed with vena cava clamping without exclusion of the liver. A reconstruction of the vena cava with a parietal peritoneum patch harvested from the posterior aponeurosis of the left rectus abdominal muscle was carried out. The segment of peritoneum was sutured into a 20 mm tubular shape with a longitudinal Prolene 5-0 running suture. The segment of peritoneal tube was sutured to the vena cava with a longitudinal Prolene 5-0 running suture (Figure 3). The thrombus was positive for both E. faecium and C. albicans.

In the days that followed, the fever abated progressively, while the sepsis disappeared and all of the repeated blood cultures remained negative. The patient was discharged on POD67 with anticoagulation treatment. She remained afebrile, and the antibiotic treatment has been terminated.

Septic thrombophlebitis related to vascular invasion from adjacent non-vascular infections is best illustrated by thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein[2]. This complication has also been reported for limb veins, portal (pylephlebitis) and mesenteric veins after abdominal infections, pelvic veins following postpartum infections, and dural sinuses[3].

Isolated septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava has been reported in a small number of cases, mainly caused by prolonged central venous catheterization, but never after hepatectomy[4-6]. Septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava is a rare disease that induce the increase of the morbidity and the mortality, as a result of sepsis and septic emboli that can cause septic pulmonary emboli and infective endocarditis[7]. The rarity of these complication results in diagnostic delay and a higher level of severity.

Optimal management of septic thrombophlebitis remains unclear due to the limited data available from comparative trials[8]. Key components comprise appropriate antibiotic treatment along with surgical or radiological drainage of the primary or secondary embolic infectious foci. Anticoagulation is an option, although it should be considered early in the management of septic thrombophlebitis in the absence of non-acceptable haemorrhagic risk[9]. Finally, endovascular or surgical thrombectomy can be an option in cases of deep vein septic thrombophlebitis that are refractory to conservative treatment[3,9,10]. In this unstable septic patient, management relied on removal of the foci of infection by surgical thrombectomy of the inferior vena cava, thereby allowing prompt and definitive control of the sepsis. In this septic environment, autologous parietal peritoneum for complete caval replacement was used to avoid reconstruction of the vena cava with synthetic materials. The parietal peritoneum was harvested from the posterior aponeurosis of the rectus abdominal muscle, thereby allowing a particularly stiff graft for support of the vena cava flow to be obtained[11]. Use of the peritoneum as a vascular graft has been reported in animal models[12] and has been described as a safe and good option for circumferential replacement of the vena cava[11,13-16]. This technique is inexpensive, it is readily and rapidly available, it uses the same surgical incision, and it allows caval replacement in a septic area.

Septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava after hepatectomy has not been described previously, and it warrants being added to the spectrum of potential complications of this procedure. A combination of antibiotic and anticoagulation treatments, prompt surgical thrombectomy, and complete caval reconstruction with a parietal peritoneum tube graft was associated with a favorable outcome in this severe case.

Septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava after hepatectomy is a rare complication of this procedure. Septic thrombophlebitis of the vena cava was successfully treated with antibiotic and anticoagulation treatments, prompt surgical thrombectomy and caval reconstruction. Use of the peritoneum as a vascular graft is an inexpensive technique, it is readily and rapidly available, and it allows caval replacement in a septic area.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P- Reviewer: Ahmed M, El-Bendary M, Garbuzenko DV, Hann HW, Luo GH, Qi XS S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | McAree BJ, O'Donnell ME, Fitzmaurice GJ, Reid JA, Spence RA, Lee B. Inferior vena cava thrombosis: a review of current practice. Vasc Med. 2013;18:32-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Lemierre A. On certain septicaemias due to anaerobic organisms. Lancet. 1936;227:701-703. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 630] [Cited by in RCA: 574] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kniemeyer HW, Grabitz K, Buhl R, Wüst HJ, Sandmann W. Surgical treatment of septic deep venous thrombosis. Surgery. 1995;118:49-53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bank ER, Glazer GM. Ultrasonographic detection of infected thrombus in the inferior vena cava. J Ultrasound Med. 1984;3:567-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Koh YX, Chng JK, Tan SG. A rare case of septic deep vein thrombosis in the inferior vena cava and the left iliac vein in an intravenous drug abuser. Ann Vasc Dis. 2012;5:389-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Benoit D, Decruyenaere J, Vandewoude K, Roosens C, Hoste E, Poelaert J, Vermassen F, Colardyn F. Management of candidal thrombophlebitis of the central veins: case report and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;26:393-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Talaie T, Drucker C, Aicher B, Khalifeh A, Lal B, Sarkar R, Toursavadkohi S. Endovascular Thrombectomy of Septic Thrombophlebitis of the Inferior Vena Cava: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2018;52:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Osowicki J, Kapur S, Phuong LK, Dobson S. The long shadow of lemierre's syndrome. J Infect. 2017;74 Suppl 1:S47-S53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Falagas ME, Vardakas KZ, Athanasiou S. Intravenous heparin in combination with antibiotics for the treatment of deep vein septic thrombophlebitis: a systematic review. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;557:93-98. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Sulaiman L, Hunter J, Farquharson F, Reddy H. Mechanical thrombectomy of an infected deep venous thrombosis: a novel technique of source control in sepsis. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:65-68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Dokmak S, Aussilhou B, Sauvanet A, Nagarajan G, Farges O, Belghiti J. Parietal Peritoneum as an Autologous Substitute for Venous Reconstruction in Hepatopancreatobiliary Surgery. Ann Surg. 2015;262:366-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Salimi F, Hodjati H, Monabbati A, Keshavarzian A. Inferior vena cava reconstruction with a flap of parietal peritoneum: an animal study. Arch Iran Med. 2009;12:448-453. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Coubeau L, Rico Juri JM, Ciccarelli O, Jabbour N, Lerut J. The Use of Autologous Peritoneum for Complete Caval Replacement Following Resection of Major Intra-abdominal Malignancies. World J Surg. 2017;41:1005-1011. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pulitano C, Crawford M, Ho P, Gallagher J, Joseph D, Stephen M, Sandroussi C. Autogenous peritoneo-fascial graft: a versatile and inexpensive technique for repair of inferior vena cava. J Surg Oncol. 2013;107:871-872. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Chin PT, Gallagher PJ, Stephen MS. Inferior vena caval resection with autogenous peritoneo-fascial patch graft caval repair: a new technique. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:391-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Pulitanó C, Crawford M, Ho P, Gallagher J, Joseph D, Stephen M, Sandroussi C. The use of biological grafts for reconstruction of the inferior vena cava is a safe and valid alternative: results in 32 patients in a single institution. HPB (Oxford). 2013;15:628-632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |