Published online Dec 27, 2018. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v10.i12.956

Peer-review started: May 23, 2018

First decision: July 10, 2018

Revised: July 10, 2018

Accepted: August 20, 2018

Article in press: August 21, 2018

Published online: December 27, 2018

Processing time: 219 Days and 8.9 Hours

To evaluate trends and disparities in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) outcomes among Hispanic patients in the United States with a focus on tumor stage at diagnosis.

We retrospectively evaluated all Hispanic adults (age > 20) with HCC diagnosed from 2004 to 2014 using United States Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) cancer registry data. Tumor stage was assessed by SEER-specific staging systems and whether HCC was within Milan criteria at diagnosis. Multivariate logistic regression models evaluated for predictors of HCC within Milan criteria at diagnosis.

Overall, Hispanics accounted for 19.8% of all HCC (73.3% men, 60.9% had Medicare or commercial insurance, 33.5% Medicaid, and 5.6% uninsured). Thirty-eight percent of Hispanic HCC patients were within Milan criteria at diagnosis. With latter time periods, significantly more patients were diagnosed with HCC within Milan criteria, and in 2013-2014, 42.6% had HCC within Milan criteria. On multivariate regression, Hispanic males (OR vs females: 0.76, 95%CI: 0.68-0.83, P < 0.001), Hispanics > 65 years (OR vs age < 50: 0.67, 95%CI: 0.58-0.79, P < 0.001), and uninsured patients (OR vs Medicare/commercial: 0.49, 95%CI: 0.40-0.59, P < 0.001) were significantly less likely to have HCC within Milan criteria at diagnosis.

While one in five HCC patients in the United States are of Hispanic ethnicity, only 38% were within Milan criteria at time of diagnosis, and thus over 60% were ineligible for liver transplantation, one of the primary curative options for HCC patients. Improved efforts at HCC screening and surveillance are needed among this group to improve early detection.

Core tip: The Hispanic population represents a major contributor to the hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) burden. However, our current study demonstrates that over 60% of Hispanic HCC patients were ineligible for liver transplantation given the extent of disease severity. This advanced cancer stage at diagnosis likely reflects suboptimal implementation of early and timely HCC screening and surveillance in high-risk populations. These findings emphasize the need to be more vigilant about HCC screening and surveillance, especially among the Hispanic population.

- Citation: Robinson A, Ohri A, Liu B, Bhuket T, Wong RJ. One in five hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the United States are Hispanic while less than 40% were eligible for liver transplantation. World J Hepatol 2018; 10(12): 956-965

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v10/i12/956.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i12.956

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the second leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide[1-3]. The number of deaths per year from HCC is nearly identical to the worldwide incidence, highlighting the incredibly high case fatality rate of this aggressive disease[3]. While the highest prevalence of HCC is among populations in Asia and Africa, the incidence of HCC has been increasing in the United States, due to the growing number of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) who are at risk for HCC[1,4-8]. However, the rising HCC incidence is not uniform across all groups, and an increasingly disproportionate rise in HCC incidence among minority groups, and in particular Hispanics, have been reported[9-13]. A recent study by White et al[7] reported a 4.5% annual increase in overall HCC incidence in the United States from 2000 to 2009. However, race/ethnicity-specific differences were observed with significantly greater increases in HCC incidence among Hispanics, such that beginning in 2012, HCC incidence among Hispanics surpassed that of Asians in the United States. While the exact etiology underlying this epidemiology is unclear, these trends likely reflect the successful impact of HBV vaccination in Asians and the emergence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in the Hispanic population. Because the Hispanic population carries a disproportionate burden of NAFLD, understanding trends in HCC among the Hispanic population in the United States may provide insight on NAFLD-HCC trends[11,14-19]. The aim of the current study is to evaluate overall trends and disparities in HCC outcomes among Hispanic HCC patients in the United States with a focus on HCC tumor stage at presentation.

The National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) population based cancer registry was reviewed to identify all Hispanic adults (age 20 years and older) with HCC from 2004 to 2014 in the United States[20]. The 2004-2014 SEER data includes data from 18 regions in the United States (San Francisco-Oakland, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta, San Jose-Monterey, Los Angeles, Alaska Natives, Rural Georgia, California excluding San Francisco/San Jose/Los Angeles, Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Greater Georgia) and represents approximately 28% of the United States population.

The International Classification of Disease for Oncology, Third Edition was used by the SEER database to define HCC[21]. HCC tumor stage was evaluated using SEER historic summary staging, which is unique to SEER and is not used particularly for prognosis, but to describe the extent of disease[21]. Tumors confined to only one lobe of the liver with or without vascular invasion were defined as localized. Tumors involving more than one lobe through contiguous growth of a single lesion, extension to adjacent structures (gallbladder, diaphragm, or extrahepatic bile ducts), or spread to regional lymph nodes were defined as regional. Metastatic disease or extension of cancer to distant lymph nodes or nearby organs such as the stomach, pleura, or pancreas was defined as distant. In addition to SEER HCC staging, we also evaluated tumor characteristics including size and number of tumors to determine whether a patient’s tumor met Milan criteria (single lesion less than 5 cm or no more than 3 lesions each less than 3 cm) with no extrahepatic or vascular involvement. We specifically chose to evaluate whether or not a patient’s tumor met Milan criteria, as this affects eligibility for liver transplantation, which is one of the major curative treatment options for HCC[22].

Insurance status was evaluated using SEER classifications, which included three categories: Medicare or commercial insurance, Medicaid, and uninsured/no insurance. Medicare or commercial insurance includes patients with private insurance (fee-for-service, managed care, HMO, PPO, Tricare) or Medicare (administered through a managed care plan, Medicare with private supplement, or Medicare with supplement, NOS and Military). Medicaid includes patients with Medicaid (including administered through managed care plans, Medicare with Medicaid eligibility, and Indian/Public Health Service). Uninsured is defined as those who were either not insured or self-pay at time of HCC diagnosis. Age-specific comparisons utilized three categories of age at time of HCC diagnosis (age < 50 years, age 50 - 64 years, and age > 65 years).

Demographic characteristics of the study cohort were presented as proportions and frequencies. Overall proportion of adult Hispanic patients with localized HCC or HCC within Milan criteria were stratified by sex, age at time of diagnosis, insurance status, and year of diagnosis, and compared across groups using χ2 test. Predictors of HCC tumor stage at presentation and HCC treatment received were evaluated using multivariate logistic regression models. Forward stepwise regression methods were used with variables demonstrating significant associations in the univariate model (P < 0.10) or those with biologic significance determined a priori (e.g., age and sex) included in the final model. Statistical significance was met with a 2-tailed P-value < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed with Stata version 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt by the Alameda Health System Institutional Review Board because human subjects were not involved, as per United States Department of Health and Human Services guidelines, and the SEER database is publicly available without individually identifiable private information.

Hispanics accounted for 19.8% of all HCC among United States adults in the 2004-2014 SEER registry, with the majority of subjects with HCC being men (n = 9856, 73.3%). Among both Hispanic men and women with HCC, 60.9% had Medicare or commercial insurance at time of HCC diagnosis, 33.5% had Medicaid, and 5.6% were uninsured (Table 1). The proportion of the HCC cohort represented by Hispanic patients increased from 17.6% in 2004-2006 to 20.1% in 2013-2014.

| Hispanics | Asians | Non-Hispanic White | ||||

| Percent (%) | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | Frequency (n) | Percent (%) | Frequency (n) | |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 26.7 | 3584 | 29.5 | 3273 | 24.9 | 9273 |

| Male | 73.3 | 9856 | 70.6 | 7840 | 75.1 | 27940 |

| Age | ||||||

| < 50 yr | 10.7 | 1440 | 10.7 | 1191 | 6.1 | 2268 |

| 50-64 yr | 47.1 | 6325 | 36.4 | 4045 | 45.6 | 16973 |

| > 65 yr | 42.2 | 5675 | 52.9 | 5877 | 48.3 | 17972 |

| Insurance | ||||||

| Medicare or Commercial | 60.9 | 5969 | 66.3 | 5177 | 80.2 | 21265 |

| Medicaid | 33.5 | 3280 | 29.5 | 2299 | 16.1 | 4257 |

| Uninsured | 5.6 | 549 | 4.3 | 335 | 3.7 | 983 |

| Year of diagnosis | ||||||

| 2004-2006 | 17.6 | 2722 | 17.6 | 2713 | 51.8 | 8009 |

| 2007-2008 | 17.4 | 2115 | 16.3 | 1985 | 52.5 | 6376 |

| 2009-2010 | 18.9 | 2550 | 15.4 | 2084 | 51.3 | 6927 |

| 2011-2012 | 20.1 | 2870 | 13.9 | 2133 | 51.9 | 7690 |

| 2013-2014 | 20.1 | 3183 | 13.9 | 2198 | 51.7 | 8211 |

| HCC SEER summary stage | ||||||

| Localized | 54 | 6091 | 51.8 | 2250 | 52.6 | 8644 |

| Regional | 29.5 | 3324 | 31 | 1345 | 31.2 | 5129 |

| Distant | 16.5 | 1858 | 15 | 747 | 16.2 | 2652 |

| HCC within Milan criteria | ||||||

| No | 62 | 8337 | 59.1 | 2832 | 55.4 | 10530 |

| Yes | 38 | 5103 | 40.9 | 1958 | 44.6 | 8465 |

When evaluating HCC tumor stage at diagnosis, 38.0% of Hispanic HCC patients were within Milan criteria, and 54.0% of Hispanic HCC patients had localized HCC (Table 2). Compared to female HCC patients, male HCC patients had significantly lower rates of localized HCC (52.8% vs 57.6%, P < 0.001) and significantly lower rates of HCC within Milan criteria (37.4% vs 39.7%, P = 0.01). Compared to HCC patients age < 50 years at time of diagnosis, higher rates of localized HCC and HCC within Milan criteria were observed in those age 50-64, but HCC patients age > 65 years had lower rates of localized HCC or HCC within Milan criteria (Table 2). Compared to Medicare or commercially insured patients, Hispanic HCC patients with Medicaid or no insurance had significantly lower rates of localized HCC or HCC within Milan criteria.

| Localized HCC at Time of diagnosis | HCC within Milan criteria at time of diagnosis | |||||

| Percent (%) | Frequency (n) | P-value | Percent (%) | Frequency (n) | P-value | |

| Total | 54 | 6091 | 38 | 5103 | ||

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 57.6 | 1680 | < 0.001 | 39.7 | 1422 | 0.01 |

| Male | 52.8 | 4411 | 37.4 | 3681 | ||

| Age | ||||||

| < 50 yr | 51.7 | 630 | < 0.01 | 36.8 | 530 | < 0.001 |

| 50-64 yr | 55.5 | 3030 | 44.6 | 2820 | ||

| > 65 yr | 52.9 | 2431 | 30.9 | 2753 | ||

| Insurance | ||||||

| Medicare or Commercial | 56.2 | 3004 | < 0.001 | 42.7 | 2547 | < 0.001 |

| Medicaid | 53.8 | 1607 | 42.9 | 1407 | ||

| Uninsured | 39.4 | 191 | 29.9 | 164 | ||

| Year of Diagnosis | ||||||

| 2004-2006 | 52.8 | 1195 | < 0.001 | 33.4 | 908 | < 0.001 |

| 2007-2008 | 31.7 | 553 | 33.8 | 714 | ||

| 2009-2010 | 52.7 | 1368 | 37.3 | 951 | ||

| 2011-2012 | 56.3 | 1368 | 40.9 | 1173 | ||

| 2013-2014 | 56.9 | 1525 | 42.6 | 1357 | ||

When stratified by year of HCC diagnosis, Hispanic HCC patients in the latter time periods had significantly higher rates of localized HCC at time of diagnosis, and in 2013-2014, 56.9% of Hispanic HCC patients had localized tumor stage. Similarly, the proportion of Hispanic patients with HCC within Milan criteria also increased with time, and in 2013-2014, 42.6% of Hispanic HCC patients were within Milan criteria (Table 3). When stratified by sex, age, and insurance status, similar trends were seen, such that HCC patients in latter time periods had the highest rates of more localized stage of disease.

| Localized HCC | Overall | Female | Male | Age < 50 | Age 50-64 | Age 65 and over | Uninsured | Medicaid | Medicare/Commercial | |||||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| 2004-2006 | 52.8 | 1195 | 58 | 342 | 51 | 853 | 48.7 | 165 | 54.1 | 544 | 52.9 | 486 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2007-2008 | 31.7 | 553 | 55.5 | 236 | 48.1 | 635 | 46 | 115 | 50.9 | 424 | 50.1 | 332 | 33.9 | 38 | 49.3 | 281 | 52.1 | 531 |

| 2009-2010 | 52.7 | 1368 | 55.3 | 588 | 51.8 | 844 | 51.5 | 121 | 55.4 | 589 | 49.6 | 422 | 36 | 40 | 52.6 | 397 | 54.4 | 675 |

| 2011-2012 | 56.3 | 1368 | 58 | 363 | 55.7 | 1005 | 60.2 | 121 | 57.5 | 706 | 54.1 | 541 | 39.6 | 53 | 56.4 | 456 | 58 | 835 |

| 2013-2014 | 56.9 | 1525 | 59.7 | 451 | 55.7 | 1074 | 56 | 108 | 57.6 | 767 | 56.1 | 650 | 46.9 | 60 | 55.5 | 473 | 58.4 | 963 |

| P-Value | < 0.001 | < 0.03 | <0.001 | < 0.02 | < 0.02 | < 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.14 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

| HCC Within Milan | Overall | Female | Male | Age < 50 | Age 50-64 | Age 65 and Over | Uninsured | Medicaid | Medicare/Commercial | |||||||||

| % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | |

| 2004-2006 | 33.4 | 908 | 34.6 | 255 | 34.3 | 653 | 32.9 | 141 | 39.9 | 462 | 26.4 | 305 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2007-2008 | 33.8 | 714 | 32.8 | 179 | 35.5 | 535 | 34.1 | 105 | 40.6 | 397 | 25.2 | 212 | 27.5 | 36 | 37.8 | 237 | 37.6 | 428 |

| 2009-2010 | 37.3 | 951 | 40.6 | 260 | 35.3 | 691 | 36.2 | 97 | 45.5 | 559 | 28.2 | 295 | 30.3 | 37 | 40.1 | 337 | 40.4 | 558 |

| 2011-2012 | 40.9 | 1173 | 41.1 | 310 | 40.2 | 863 | 40.8 | 92 | 47.7 | 676 | 33.1 | 405 | 30.7 | 47 | 47.5 | 420 | 42.4 | 687 |

| 2013-2014 | 42.6 | 1357 | 46.1 | 418 | 36.8 | 939 | 41.2 | 95 | 47.1 | 726 | 30.9 | 536 | 30.8 | 44 | 44.2 | 413 | 47.8 | 874 |

| P-Value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.3 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | 0.92 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | |||||||||

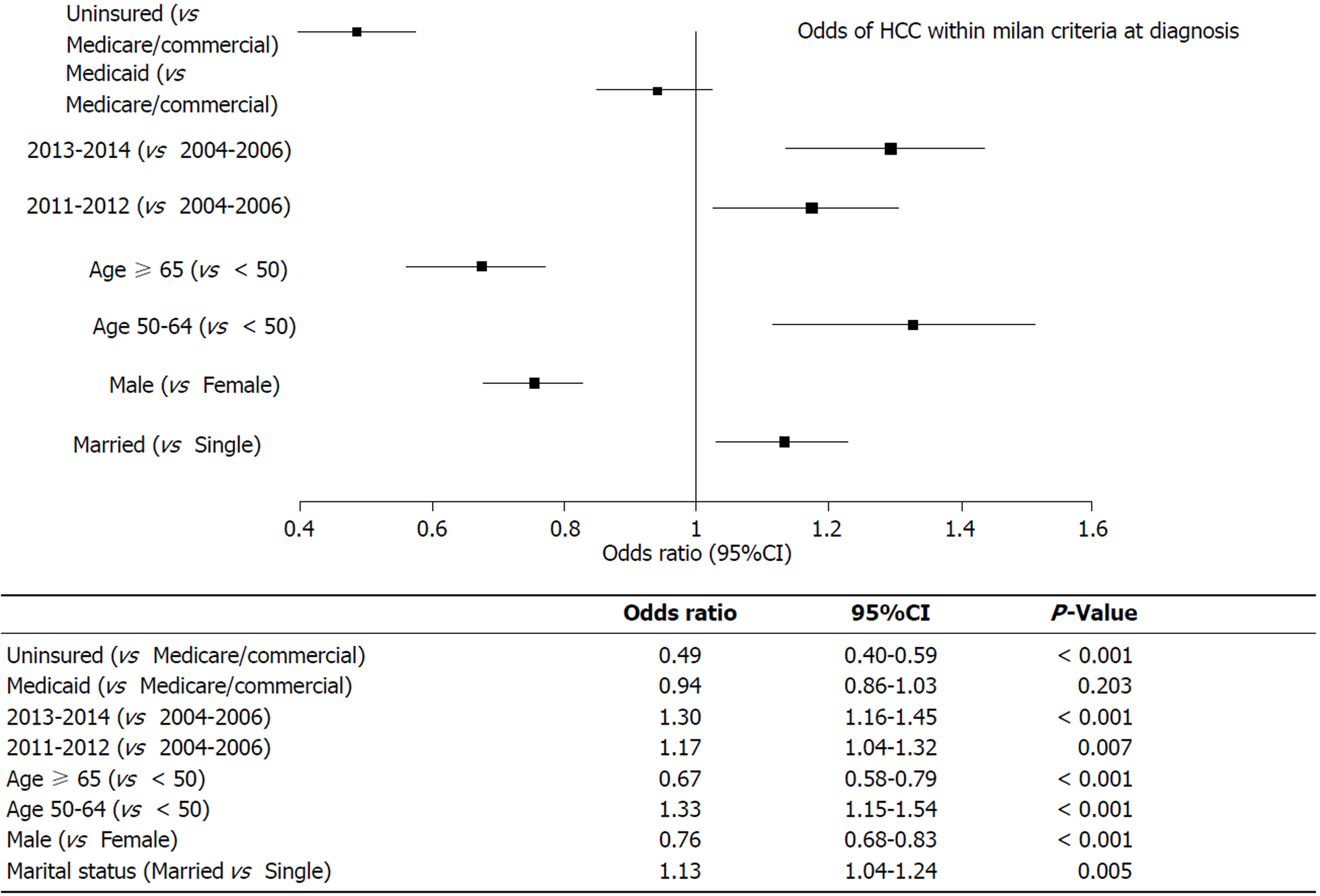

On multivariate regression, in comparison to Medicare/commercially insured Hispanic HCC patients, uninsured patients were significantly less likely to have HCC within Milan criteria at time of diagnosis (OR 0.49, 95%CI: 0.40-0.59, P < 0.001), whereas no significant difference was observed in Medicaid HCC patients (Figure 1). Compared to 2004-2006, Hispanic HCC patients in both the 2011-2012 and 2013-2014 cohorts were significantly more likely to have HCC within Milan criteria at diagnosis (2011-2012: OR 1.17, 95%CI: 1.04-1.32, P = 0.007; 2013-2014: OR 1.30, 95%CI: 1.16-1.45, P < 0.001). Compared to patients age < 50 years at the time of diagnosis, Hispanic HCC patients age 65 years and older were significantly less likely to have HCC within Milan criteria (OR 0.67, 95%CI: 0.58-0.79, P < 0.001), whereas patients age 50-64 years old were significantly more likely to have HCC within Milan criteria (OR 1.33, 95%CI: 1.15-1.54, P < 0.001). Males were less likely than females to be within Milan criteria (OR 0.76, 95%CI: 0.68-0.83, P < 0.001) (Figure 1).

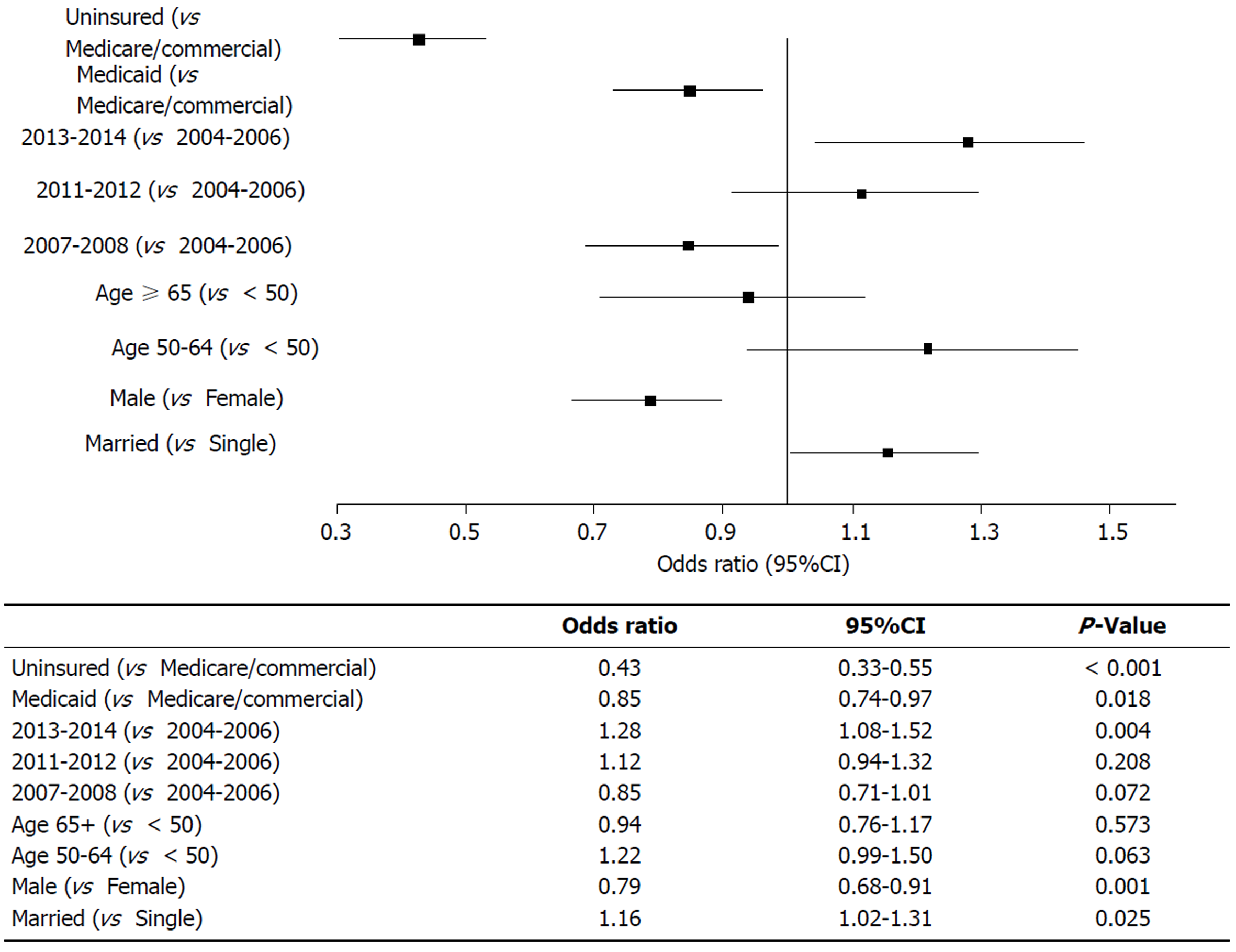

Similar trends were observed when evaluating predictors of SEER localized stage of HCC at diagnosis. Uninsured Hispanic HCC patients and those with Medicaid were significantly less likely to have localized disease compared to those patients with Medicare or commercial insurance (Uninsured: OR 0.43, 95%CI: 0.33-0.55, P < 0.001, Medicaid: OR 0.85, 95%CI: 0.74-0.97, P = 0.018). Patients diagnosed with HCC during 2013-2014 were more likely to have localized disease as compared to those diagnosed from 2004-2006 (OR: 1.28, 95%CI: 1.08-1.52, P = 0.004), however there was no significant difference when comparing 2011-2012 or 2007-2008 to 2004-2006. Males were less significantly less likely to have localized disease compared to females (OR 0.79, 95%CI: 0.68-0.91, P = 0.001) (Figure 2).

Using United States population-based cancer registry data, the current study evaluated disparities in HCC tumor stage at diagnosis with a focus on Hispanics with HCC. Overall, the proportion of HCC in the Hispanic population increased during the study period such that over 20% of HCC patients in the United States during 2013-2014 were of Hispanic ethnicity. Despite this huge disease burden among the Hispanic population, less than half of Hispanic HCC patients were within Milan criteria at the time of diagnosis in the most recent time period studied. Furthermore, significant disparities among this group were observed, with a disproportionately higher risk of advanced tumor stage at presentation among Hispanic men, older Hispanic patients, and uninsured Hispanic patients.

Nearly one in five HCC patients in the United States are of Hispanic ethnicity with Hispanic patients showing the greatest increase in the incidence of HCC from 2004-2006 to 2013-2014[20]. These observations are consistent with previous SEER registry based studies evaluating trends in HCC incidence. For example, El-Serag et al[23] reported significantly greater age-adjusted HCC incidence rates in Hispanic patients in comparison to non-Hispanic white and black populations between 1992 and 2002. This increasing HCC incidence among the Hispanic population in the United States has continued to rise such that HCC incidence among Hispanics surpassed HCC incidence among Asians in 2012 to become the ethnic group with the greatest incidence of HCC in the United States and representing over 20% of all HCC among adults in the United States[7]. While our current study is limited by the ability to evaluate the liver disease etiology contributing to HCC, the Hispanic population in the United States carries a disproportionate burden of NAFLD[14-17,24-28]. Furthermore, during this same period where Hispanics have become the ethnic group with the most rapidly rising incidence of HCC, it is also important to note that prevalence of NASH-related HCC has also risen in parallel[8,18,26,29-31]. Two recent studies using the SEER-Medicare database and the United Network for Organ Sharing registry demonstrate the continued rising prevalence of NAFLD-related HCC in the United States[8,18].

While the growing burden of HCC among the Hispanic population is concerning, it is even more alarming that the Hispanic population faces significant disparities in access to treatment options for HCC, which contributes to significantly lower survival[32-35]. A recent study by Ha et al[34] using the SEER database found that Hispanic patients with HCC had significantly lower rates of curative HCC treatment when compared to non-Hispanic whites. Hispanics were also significantly less likely to receive liver transplantation even after correcting for stage of disease at time of diagnosis. Our current analysis of the most recent SEER database continues to highlight these disparities among the Hispanic HCC population. Despite improvements in earlier tumor stage of diagnosis over time, even in the most recent 2013-2014 period only 42.6% of Hispanic HCC patients were within Milan criteria at the time of diagnosis, which means that nearly 60% of patients were not eligible for liver transplantation, one of the main curative options for HCC patients.

A greater frequency of HCC was observed among male patients within our study, which is consistent with prior data showing HCC rates in males are two to four times as high as rates in females[35,36]. This sex-specific trend in HCC risk is also observed among NAFLD HCC populations. Corey et al[36] evaluated at risk factors for HCC in 94 patients with NAFLD with HCC and 150 patients with NAFLD without HCC. The strongest association with risk of HCC was being male, with males having a four-fold higher risk of developing HCC compared to females. The majority of Hispanic HCC patients in our study were men, and they had more advanced HCC at diagnosis compared to females. Similarly Yang et al[37] observed significantly better outcomes in females with HCC. In their study of primarily non-Hispanic Caucasian patients, the distribution of tumor burden showed a higher incidence of single lesions among women and a higher incidence of vascular invasion among men.

Our study utilized a large population-based cancer registry, which represents a large proportion of the United States population. The SEER registry allowed for a large sample size and comprehensive analysis of HCC epidemiology and outcomes. Despite this, the current study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. SEER does not include etiology of HCC (e.g., chronic hepatitis B virus, chronic HCV, alcoholic liver disease, or NAFLD), which may have affected rates of disease progression or rates of timely HCC screening and surveillance. Along the same lines, liver disease-specific treatment data (e.g., antiviral therapies) were not available for inclusion in the analysis. While our study observed more advanced tumor stage among older patients, this observation may be confounded by other factors. Older patients may have had more significant co-morbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or cardiac disease) that may have affected referral for HCC screening and surveillance. However, these additional co-morbidities and risk factors such as alcohol use, obesity, and concurrent diabetes mellitus were not available in the database for inclusion in our analyses. While our study also investigated disparities related to insurance status, we acknowledge that insurance status is only one key factor that is tightly linked to other demographic and socioeconomic factors in a complex manner. Furthermore, in the SEER database, Medicare and commercially insured patients are combined into one category, and demographic and clinical differences between those with Medicare and commercial insurance may affect HCC stage at diagnosis. However, access to care, including HCC screening and surveillance that would affect tumor stage and HCC treatment are expected to be similar between those with Medicare and commercial insurance in the United States. While our study found significant disparities in HCC stage among uninsured patients, these differences may reflect difficulty accessing healthcare due to complex socioeconomic needs. However, these data were not available to assess further in the database. Another factor not readily available for analysis is concurrent substance use and high-risk behavior, which may have affected timely access and adherence to HCC surveillance. Lastly, surveillance data were not available to evaluate how the differences in successful screening and surveillance rates contributed to the observed disparities in HCC stage at diagnosis. Despite these limitations, our study provides valuable information regarding a vulnerable subset of the United States population.

Understanding HCC trends provides valuable data to guide clinicians and policy makers to identify high-risk groups as well as those that suffer disparities towards which resources can be targeted to improve HCC screening and surveillance for early detection and treatment. Our current study focused specifically on Hispanic HCC patients, a group that has the highest incidence of HCC in the United States since 2012 and represents 20% of all adults with HCC. Among this group less than 40% had HCC within Milan criteria at the time of diagnosis, and thus over 60% were ineligible for liver transplantation, one of the major curative options for HCC patients. Part of this problem revolves around effective HCC screening and surveillance, and despite established guidelines, overall HCC screening rates remain low[38-40]. In one United States population-based study, less than 20% of patients with cirrhosis who developed HCC received regular surveillance, and only 29% of patients who had a diagnosis of HCC had undergone annual surveillance in the three years before receiving the diagnosis[41]. Tavakoli et al[42] observed that less than half of cirrhotic patients received first time HCC screening among safety-net populations with cirrhosis, with the largest disparity occurring among patients with NASH cirrhosis. Improved efforts at HCC screening and surveillance are needed, particularly among Hispanic patients, a growing population with a high prevalence of NAFLD.

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The Hispanic population represents a major contributor of HCC prevalence, particularly in the United States. Understanding HCC epidemiology and disparities in HCC outcomes among this cohort will help guide interventions to improve HCC care.

Given the significant burden of HCC among the Hispanic population, understanding HCC epidemiology and outcomes among this group is critical. Data gathered from studying HCC epidemiology can help identify potential areas where quality improvement programs can be developed and implemented to improve management of HCC.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate disparities in cancer stage at diagnosis among Hispanic HCC patients.

The current study utilized a large United States national-based cancer registry. We utilized a retrospective observational cohort study design to evaluate HCC epidemiology and outcomes among Hispanic adults diagnosed with HCC from 2004 to 2014.

We identified that over 60% of Hispanic HCC patients were diagnosed with advanced cancer stage that was beyond eligibility for liver transplantation. This highlights an important disparity and may reflect suboptimal utilization of timely HCC screening and surveillance among this population.

These findings may suggest that the Hispanic population at risk for HCC may experience suboptimal receipt of or delays in timely HCC screening and surveillance. These study findings further add to the existing literature highlighting the poor adherence to HCC screening and surveillance among at-risk populations. Specifically, our study identified a high-risk group in the Hispanic population, which is particularly concerning given the higher risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in this population, a disease that is increasing in prevalence.

Our study findings emphasize the importance of timely and consistent implementation of HCC screening and surveillance that will translate into improved early HCC detection. This will ultimately improve treatment options for curative intent and thus improve long-term survival outcomes among HCC patients.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P- Reviewer: Kohla MAS, Roohvand F, Sugimura H S- Editor: Cui LJ L- Editor: Filipodia E- Editor: Tan WW

| 1. | El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118-1127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2881] [Cited by in RCA: 3088] [Article Influence: 220.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Forner A, Llovet JM, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2012;379:1245-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3249] [Cited by in RCA: 3593] [Article Influence: 276.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 3. | Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2017. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017;67:7-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11065] [Cited by in RCA: 12184] [Article Influence: 1523.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 4. | Ahmed F, Perz JF, Kwong S, Jamison PM, Friedman C, Bell BP. National trends and disparities in the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, 1998-2003. Prev Chronic Dis. 2008;5:A74. [PubMed] |

| 5. | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1264-1273.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2183] [Cited by in RCA: 2504] [Article Influence: 192.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, Bhuket T, Tana MM, Liu B, Gish RG, Wong RJ. Race/ethnicity-specific disparities in cancer incidence, burden of disease, and overall survival among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2016;122:2512-2523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | White DL, Thrift AP, Kanwal F, Davila J, El-Serag HB. Incidence of Hepatocellular Carcinoma in All 50 United States, From 2000 Through 2012. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:812-820.e5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 331] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 8. | Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology. 2014;59:2188-2195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 520] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Article Influence: 53.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Njei B, Rotman Y, Ditah I, Lim JK. Emerging trends in hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and mortality. Hepatology. 2015;61:191-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 427] [Cited by in RCA: 432] [Article Influence: 43.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Altekruse SF, Henley SJ, Cucinelli JE, McGlynn KA. Changing hepatocellular carcinoma incidence and liver cancer mortality rates in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:542-553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 334] [Cited by in RCA: 355] [Article Influence: 32.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Rich NE, Hester C, Odewole M, Murphy CC, Parikh ND, Marrero JA, Yopp AC, Singal AG. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Presentation and Outcomes of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 27.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Roskilly A, Rowe IA. Surveillance for hepatocellular cancer. Clin Med (Lond). 2018;18:s66-s69. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Russo FP, Imondi A, Lynch EN, Farinati F. When and how should we perform a biopsy for HCC in patients with liver cirrhosis in 2018? A review. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50:640-646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Browning JD, Szczepaniak LS, Dobbins R, Nuremberg P, Horton JD, Cohen JC, Grundy SM, Hobbs HH. Prevalence of hepatic steatosis in an urban population in the United States: impact of ethnicity. Hepatology. 2004;40:1387-1395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2633] [Cited by in RCA: 2694] [Article Influence: 128.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 15. | Lazo M, Hernaez R, Eberhardt MS, Bonekamp S, Kamel I, Guallar E, Koteish A, Brancati FL, Clark JM. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States: the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988-1994. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:38-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 633] [Cited by in RCA: 625] [Article Influence: 52.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Vernon G, Baranova A, Younossi ZM. Systematic review: the epidemiology and natural history of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis in adults. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34:274-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2405] [Cited by in RCA: 2290] [Article Influence: 163.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Williams CD, Stengel J, Asike MI, Torres DM, Shaw J, Contreras M, Landt CL, Harrison SA. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis among a largely middle-aged population utilizing ultrasound and liver biopsy: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1522] [Cited by in RCA: 1619] [Article Influence: 115.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afendy M, Fang Y, Younossi Y, Mir H, Srishord M. Changes in the prevalence of the most common causes of chronic liver diseases in the United States from 1988 to 2008. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:524-530.e1; quiz e60. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 758] [Cited by in RCA: 790] [Article Influence: 56.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wong A, Le A, Lee MH, Lin YJ, Nguyen P, Trinh S, Dang H, Nguyen MH. Higher risk of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hispanic patients with hepatitis C cirrhosis and metabolic risk factors. Sci Rep. 2018;8:7164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Surveillance E. End Results (SEER) Program (www.seer.cancer. gov) SEER*Stat Database: Incidence. SEER 9 Regs Research Data, Nov 2016; Sub (1973-2014). Linked To County Attributes. April 2017, 1969-2015. |

| 21. | Adamo M, Dickie , L , Ruhl J. SEER Program Coding and Staging Manual 2016. National Cancer Institute, United States, Bethesda, 20850-29765. . |

| 22. | Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, Sirlin CB, Abecassis MM, Roberts LR, Zhu AX, Murad MH, Marrero JA. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2018;67:358-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2107] [Cited by in RCA: 3014] [Article Influence: 430.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 23. | El-Serag HB, Lau M, Eschbach K, Davila J, Goodwin J. Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Hispanics in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1983-1989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Welzel TM, Graubard BI, Quraishi S, Zeuzem S, Davila JA, El-Serag HB, McGlynn KA. Population-attributable fractions of risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1314-1321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 255] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Graham RC, Burke A, Stettler N. Ethnic and sex differences in the association between metabolic syndrome and suspected nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a nationally representative sample of US adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49:442-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rinella ME. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;313:2263-2273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1508] [Cited by in RCA: 1753] [Article Influence: 175.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Schneider AL, Lazo M, Selvin E, Clark JM. Racial differences in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the U.S. population. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2014;22:292-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Negro F, Hallaji S, Younossi Y, Lam B, Srishord M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in lean individuals in the United States. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91:319-327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 400] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, Perumpail RB, Harrison SA, Younossi ZM, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148:547-555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1211] [Cited by in RCA: 1382] [Article Influence: 138.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 30. | Angulo P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1221-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3655] [Cited by in RCA: 3717] [Article Influence: 161.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 31. | Charlton M. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a review of current understanding and future impact. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:1048-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 268] [Cited by in RCA: 276] [Article Influence: 13.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Alawadi ZM, Phatak UR, Kao LS, Ko TC, Wray CJ. Race not rural residency is predictive of surgical treatment for hepatocellular carcinoma: Analysis of the Texas Cancer Registry. J Surg Oncol. 2016;113:84-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Artinyan A, Mailey B, Sanchez-Luege N, Khalili J, Sun CL, Bhatia S, Wagman LD, Nissen N, Colquhoun SD, Kim J. Race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status influence the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2010;116:1367-1377. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 13.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Ha J, Yan M, Aguilar M, Tana M, Liu B, Frenette CT, Bhuket T, Wong RJ. Race/Ethnicity-specific Disparities in Hepatocellular Carcinoma Stage at Diagnosis and its Impact on Receipt of Curative Therapies. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:423-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wong RJ, Devaki P, Nguyen L, Cheung R, Nguyen MH. Ethnic disparities and liver transplantation rates in hepatocellular carcinoma patients in the recent era: results from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results registry. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:528-535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Corey KE, Gawrieh S, deLemos AS, Zheng H, Scanga AE, Haglund JW, Sanchez J, Danford CJ, Comerford M, Bossi K. Risk factors for hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhosis due to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A multicenter, case-control study. World J Hepatol. 2017;9:385-390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yang D, Hanna DL, Usher J, LoCoco J, Chaudhari P, Lenz HJ, Setiawan VW, El-Khoueiry A. Impact of sex on the survival of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results analysis. Cancer. 2014;120:3707-3716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Singal AG, Li X, Tiro J, Kandunoori P, Adams-Huet B, Nehra MS, Yopp A. Racial, social, and clinical determinants of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance. Am J Med. 2015;128:90.e1-90.e7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 103] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Singal AG, Yopp A, S Skinner C, Packer M, Lee WM, Tiro JA. Utilization of hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance among American patients: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:861-867. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 229] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | van Meer S, de Man RA, Coenraad MJ, Sprengers D, van Nieuwkerk KM, Klümpen HJ, Jansen PL, IJzermans JN, van Oijen MG, Siersema PD. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma is associated with increased survival: Results from a large cohort in the Netherlands. J Hepatol. 2015;63:1156-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 10.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Davila JA, Morgan RO, Richardson PA, Du XL, McGlynn KA, El-Serag HB. Use of surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma among patients with cirrhosis in the United States. Hepatology. 2010;52:132-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 20.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tavakoli H, Robinson A, Liu B, Bhuket T, Younossi Z, Saab S, Ahmed A, Wong RJ. Cirrhosis Patients with Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis Are Significantly Less Likely to Receive Surveillance for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2174-2181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |