Copyright

©The Author(s) 2021.

World J Hepatol. Mar 27, 2021; 13(3): 300-314

Published online Mar 27, 2021. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i3.300

Published online Mar 27, 2021. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v13.i3.300

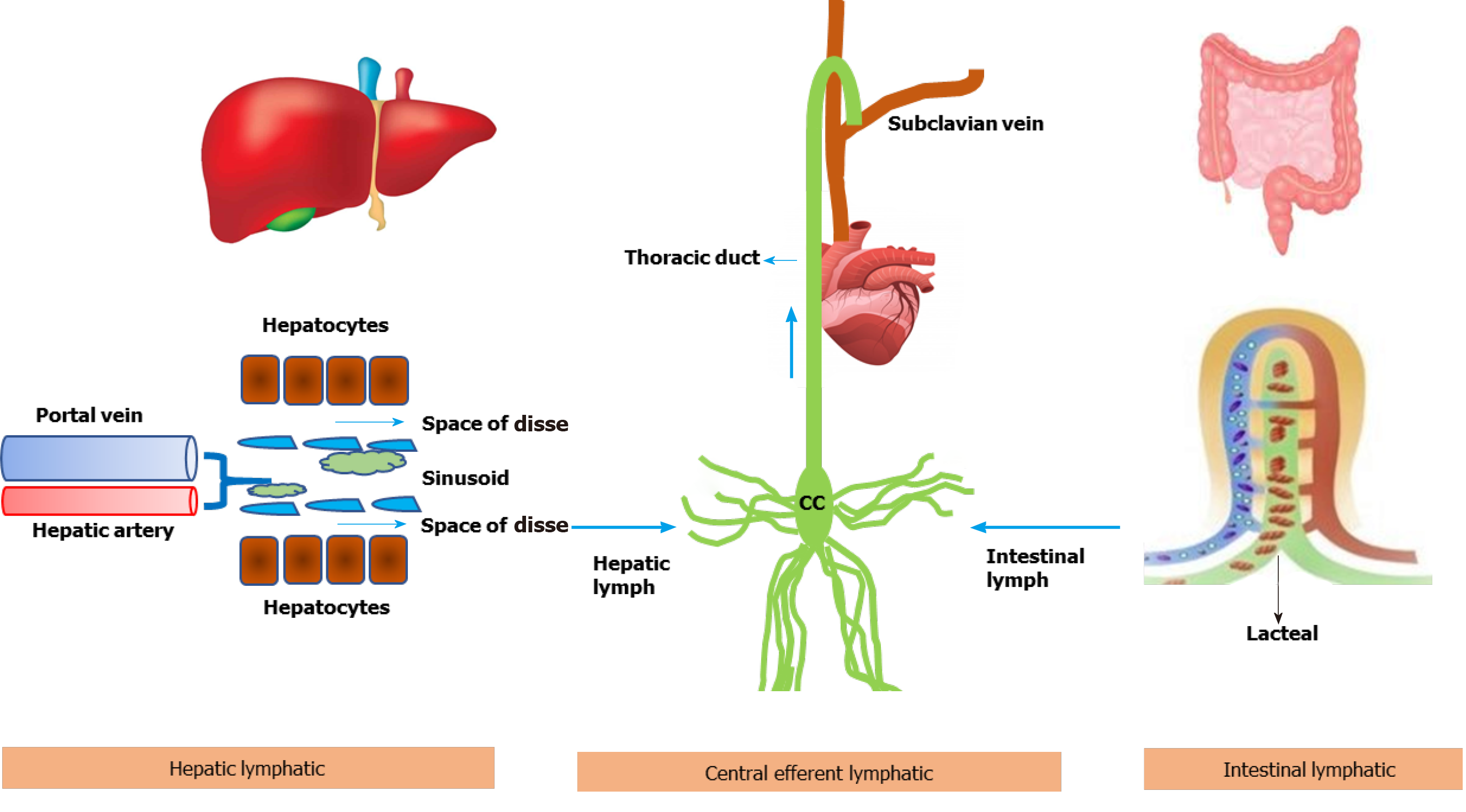

Figure 1 Schematic diagram showing lymph flow kinetics from liver and intestine to the systemic circulation.

The capillary filtrate enters the lymphatic capillaries, as lymph, and moves towards larger lymphatic vessels. In liver, lymph is produced by filtration of plasma through the sinusoidal endothelial cells into the space of Disse. The collecting lymphatic vessels from all organs connect to one or more lymph nodes, and finally to the lymph trunks which ultimately drain into subclavian vein via cysterna chyli and thoracic duct. Approximately 80% of thoracic duct lymph comes from the intestines and liver.

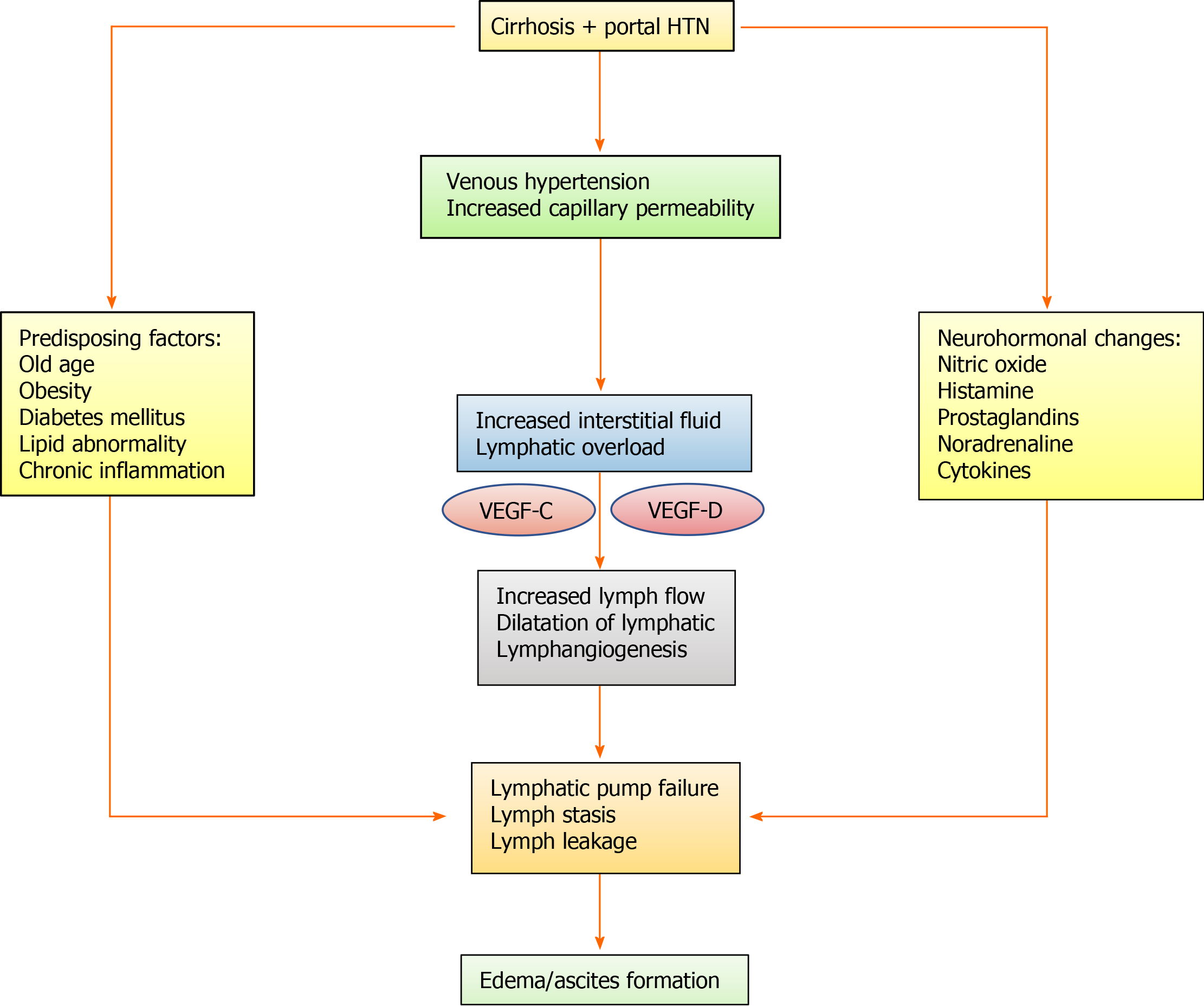

Figure 2 Flow diagram showing the possible pathophysiological mechanism behind lymphatic abnormalities in cirrhosis patients leading to fluid imbalance.

The exact pathophysiological mechanism, at cellular and molecular level, is poorly understood in human cirrhosis. Some of the information has been derived from the experimental study on animal. VEGF: Vascular endothelial growth factor; HTN: Hypertension.

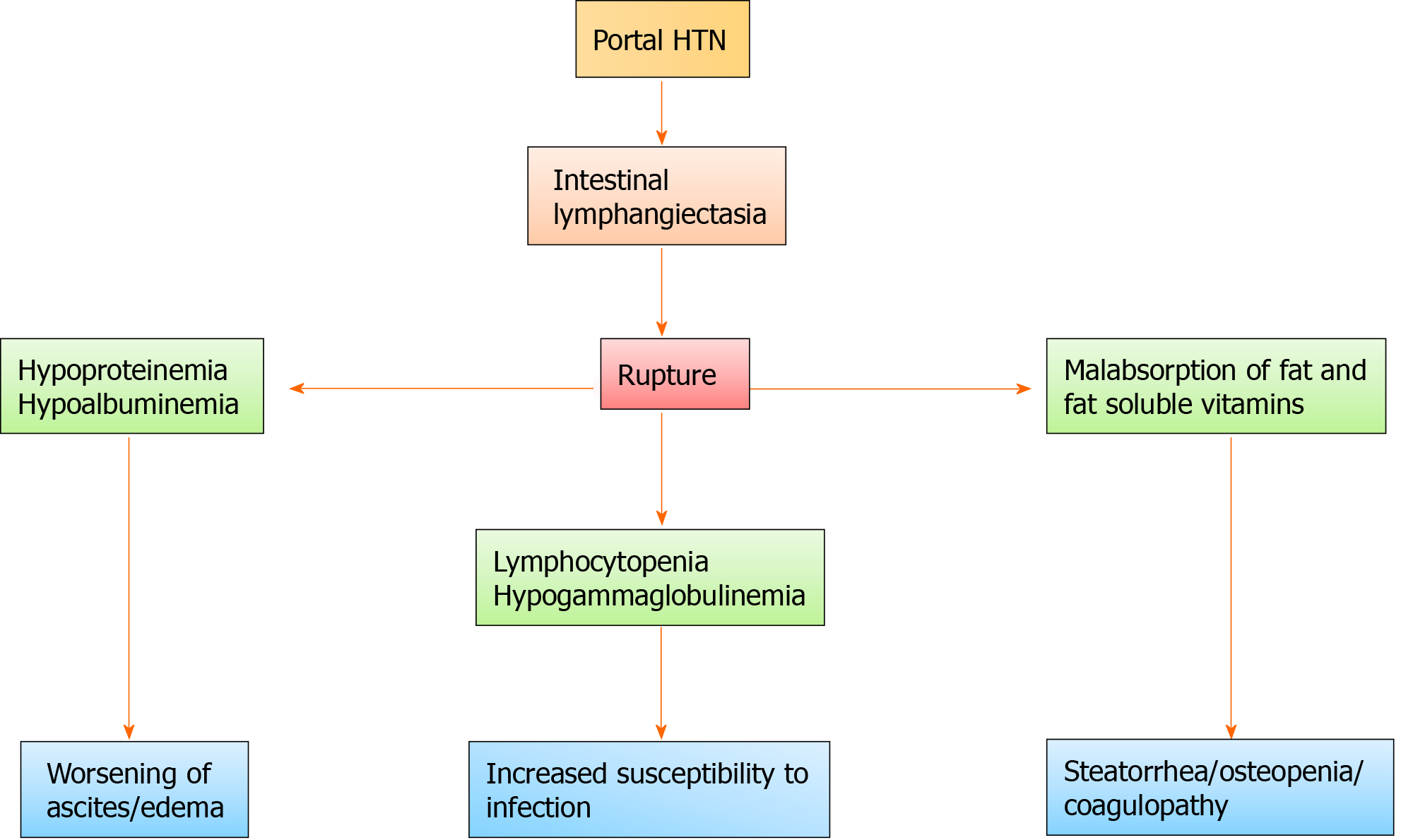

Figure 3 Flow diagram showing clinical consequences arising from the rupture of intestinal lymphangiectasia.

HTN: Hypertension.

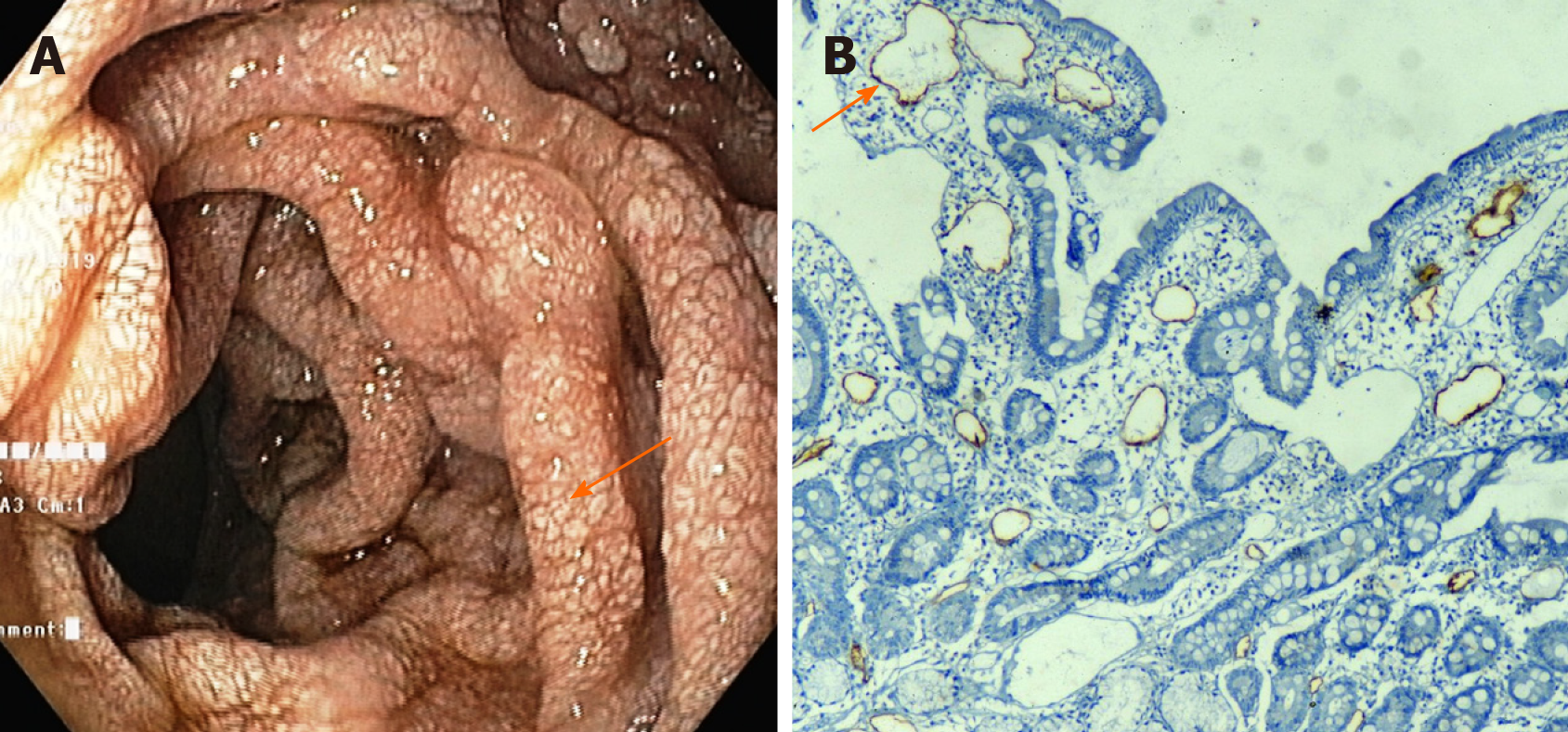

Figure 4 Intestinal lymphangiectasia in a patient with cirrhosis.

A: Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy of a patient showing whitish swollen villi in the duodenum, suggestive of intestinal lymphangiectasia; B: On immunohistochemistry (× 10), markedly dilated vessels were seen in the lamina which showed strong D2-40 positivity indicating dilated lymphatics.

- Citation: Kumar R, Anand U, Priyadarshi RN. Lymphatic dysfunction in advanced cirrhosis: Contextual perspective and clinical implications. World J Hepatol 2021; 13(3): 300-314

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1948-5182/full/v13/i3/300.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v13.i3.300