修回日期: 2021-08-30

接受日期: 2021-09-29

在线出版日期: 2021-12-08

潘氏细胞(paneth cell, PC)是由肠道干细胞(intestinal stem cells, ISC)分化而来并定居于小肠隐窝底部的分泌性细胞, 是肠道健康的重要"守卫者". PC可分泌多种抗菌肽和细胞因子以调节肠道稳态与免疫反应, 还可以合成分泌多种生长因子维持ISC的生态位, 调控ISC增殖分化, 甚至可作为静态干细胞库, 在肠组织受损时获得干细胞样特性促进组织再生, 从而有助于修复受损的肠组织. 此外, PC与一些影响肠道健康的疾病密切相关, 如炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)和结直肠癌(colorectal cancer, CRC), 对于PC的研究或许可以为这些疾病的治疗提供思路. 由此可见, PC功能的正常在维持肠道生理作用中值得高度重视.

核心提要: 潘氏细胞(paneth cell, PC)是由肠道干细胞分化并定居于小肠隐窝底部的分泌性细胞, 当肠道微环境发生改变时, 可分泌多种抗菌肽和细胞因子以调节肠道稳态、肠道干细胞增殖分化和修复损伤肠组织, 对维持肠道的稳态与健康至关重要.

引文著录: 韩怡敏, 高晗, 华嵘暄, 梁宸, 郭玥昕, 尚宏伟, 路欣, 徐敬东. Paneth cell与肠道健康. 世界华人消化杂志 2021; 29(23): 1362-1372

Revised: August 30, 2021

Accepted: September 29, 2021

Published online: December 8, 2021

Paneth cells (PC) are a group of secretory cells derived from intestinal stem cells (ISC) and colonized in the bottom of the small intestinal crypt. As an important "guardian" of intestinal health, PC can not only secrete a variety of antibacterial peptides and cytokines to regulate intestinal homeostasis and participate in immune responses, but also release growth factors to support the stem cell niche and regulate their proliferation and differentiation. Of particular concern, as a static stem cell pool, PC can acquire a stem cell-like transcriptome after the injury of intestinal tissue so as to promote regeneration and repair the damaged intestinal tissue. Particularly, PC are closely related to a number of diseases that affect intestinal health, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and colorectal cancer (CRC). The research of biological functions of PC may provide ideas for the treatment of these diseases. In summary, the role of PC in maintaining intestinal health should not be underestimated.

- Citation: Han YM, Gao H, Hua RX, Liang C, Guo YX, Shang HW, Lu X, Xu JD. Paneth cells and intestinal health. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2021; 29(23): 1362-1372

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v29/i23/1362.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v29.i23.1362

潘氏细胞(paneth cell, PC)由肠道干细胞(intestinal stem cells, ISC)分化而来并定居于小肠隐窝底部, 作为一种分泌性细胞在肠道健康与粘液细胞之间的平衡中发挥了不可或缺的作用. PC不仅可以分泌多种抗菌肽调节肠道稳态与免疫反应, 还可以分泌生长因子以维持肠道干细胞的生态位, 甚至作为静态干细胞库, 参与肠道上皮损伤后的再生, 与一些长久以来困扰医务人员的肠道疾病, 如炎症性肠病和结直肠癌密切相关. 本文基于对PC的形态、分化、功能以及与肠道疾病关系的研究进展, 对PC在肠道健康的重要作用予以综述.

PC最初在1872年由Schwalbe发现, 后在1888年由Josef Paneth完全表征并被描述为富含胞质颗粒的锥体形上皮细胞, 常三五成群聚集于小肠隐窝(即"Lieberkühn隐窝")底部[1]. 电镜下PC具有分泌型细胞的超微结构特点, 胞质富含内质网、高尔基体以及特征性的顶端聚集圆形分泌颗粒[2], 颗粒大小和电子密度稍有不同, 在2.9万倍电镜下可看到大多数为细小点状颗粒, 少部分为粗颗粒[3]. 人在妊娠13.5周的结肠和小肠中可明显观察到PC, 而17周后主要局限于小肠[4]. 成人PC主要位于胃十二指肠交界处至回肠瓣, 并向回肠方向增加, 胃中没有PC, 盲肠至横结肠含有少数, 而在乙状结肠或直肠罕见[5]. 但病理情况下, PC可出现在胃和结肠上皮化生部位, 特别值得关注的是PC可出现在前列腺或者尿道等非消化器官, 而这些部位多与细菌感染的适应性反应有关[1].

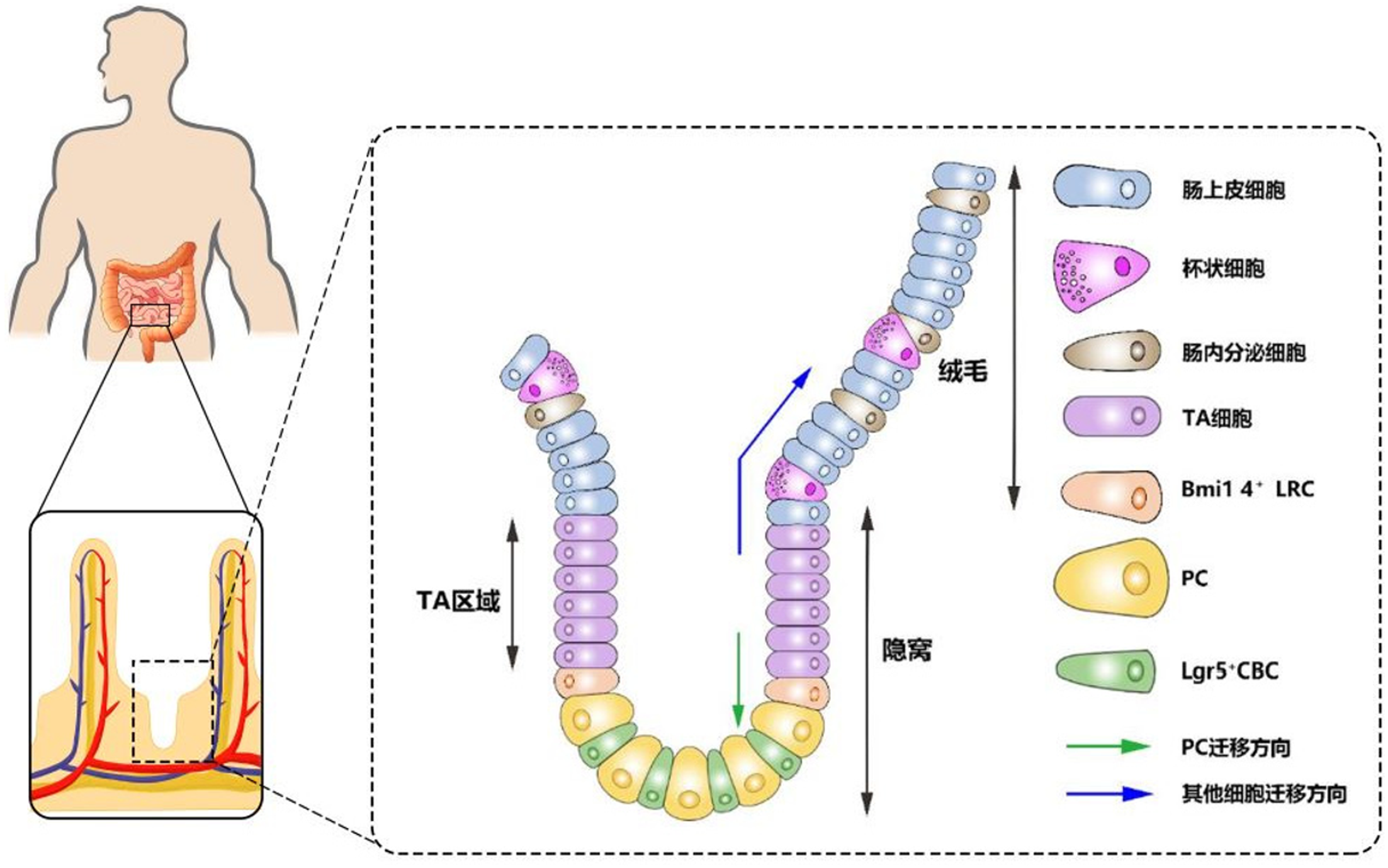

肠上皮细胞的快速更新依赖于隐窝部ISC的增殖分化, 而现已发现两种ISC: 一种是特异表达Lgr5+的隐窝基底柱状干细胞(crypt base columnar stem cell, CBC)(见图1)[6], 可分裂并产生祖细胞进入过渡扩增(transit-amplifying, TA)区域, TA细胞继续增殖并向上迁移至隐窝-绒毛连接处分化为不同类型细胞: 肠上皮细胞、杯状细胞、肠内分泌细胞和PC. 继而PC向下迁移至隐窝底部, 寿命长达1个月或更长时间, 而其他3种细胞会像"传送带"一样向上移动至绒毛顶端发挥各自的生物学作用, 并最终脱落到肠腔, 平均寿命约4-5天[2,6,7]; 另一种是特异表达Bmi1 4+的标记滞留细胞(label retaining cells, LRC)(见图1)[8], 分裂周期较长, 但可因Lgr5+CBC受损而被激活, 进行快速增殖分化[9].

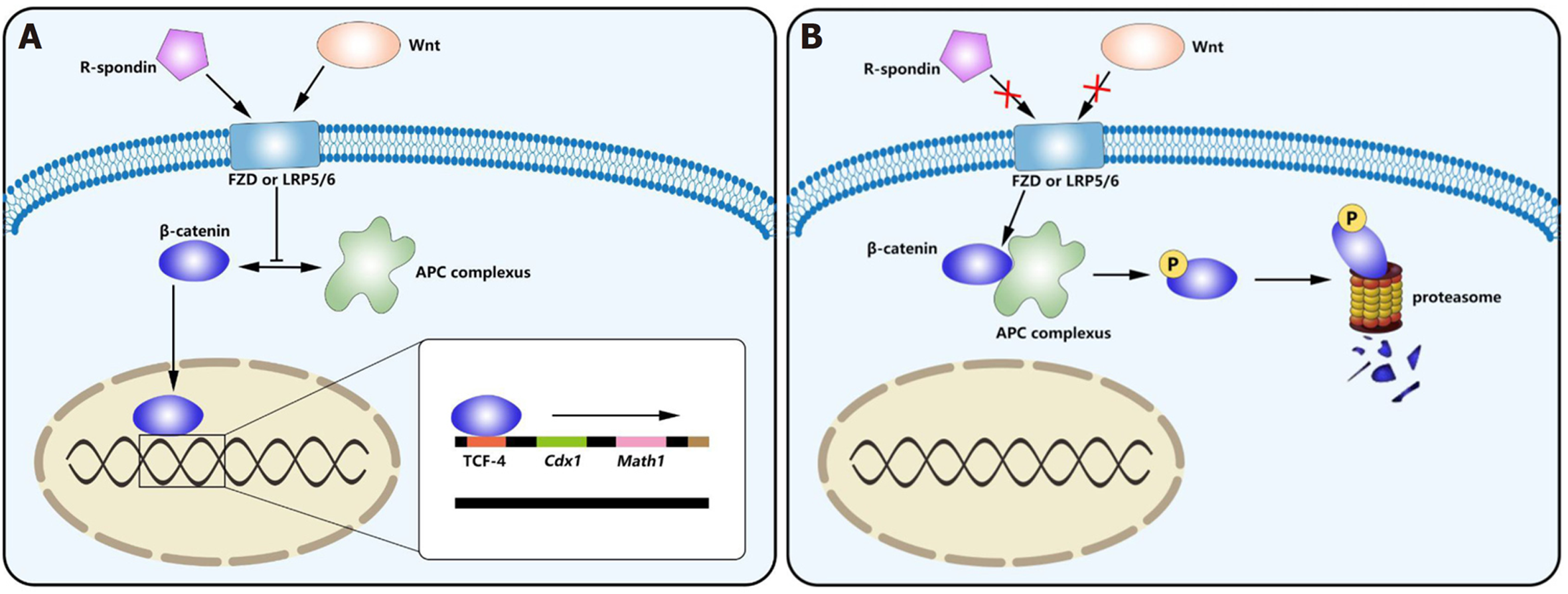

ISC增殖分化为PC的过程受多种信号通路调节, 其中Wnt通路发挥了重要作用. 经典Wnt信号通路(见图2)的核心是β-catenin的稳定及其与T细胞转录因子(T cell transcription factor 4, TCF-4)的相互作用[10,11]. 在缺乏Wnt配体(见表1)时, β-catenin可被结肠腺瘤样息肉蛋白(adenomatosis polyposis coli, APC)、GSK-3β、Axin, DVL和CK1形成的APC复合体磷酸化, 继而经泛素化并被蛋白酶体降解失去活性[12,13]. Wnt信号减少的Tcf7L2-/-小鼠小肠绒毛和上皮细胞数量减少, 存活率显著降低[14]. 而当Wnt配体与Wnt受体FZD或LRP5/6结合时[13], 可抑制APC复合体对β-catenin磷酸化作用, 从而β-catenin可移入细胞核与TCF-4相互作用后调控下游靶基因的表达[10,11,13]. 与PC分化相关的下游靶基因有: Cdx1[15]、Math1[16]、c-Myc[17]、Sox9[18]、EphB2、EphB3[19], Rac1[20]. 研究发现隐窝中Cdx1和绒毛中Cdx2的相对表达在诱导肠上皮细胞分化中发挥了重要作用[15,18], 与受β-catenin-TCF4复合体直接调控的Cdx1不同的是, Cdx2受Sox9的调控, Sox9可通过抑制成熟绒毛细胞中Cdx2和Muc2的表达来间接抑制分化过程[18]. Math1和Rac1可调控肠上皮细胞分化但均不影响细胞增殖, 通过对Math1-/-小鼠的研究表明PC、杯状细胞和肠内分泌细胞的分化取决于Math-1[16]; Rac1突变则会抑制肠上皮分化和其沿隐窝-绒毛的迁移[20]. 有研究表明EphB2-/-/EphB3-/-小鼠的肠道增殖区域和分化区域混杂在一起, 在EphB3-/-的成年鼠中, PC未遵循向下的迁移路径而是沿隐窝和绒毛散布, 导致肠道原有细胞分布发生紊乱[19], 由此可见, Ephb2和Ephb3对于PC在隐窝底部的定位发挥关键作用. 此外, Wnt信号还可直接影响丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinase, MAPK)的活性, MAPK具有调节谱系分化和使PC成熟的作用, 当MAPK受损时, 只有未成熟的PC存在. MAPK也可以通过TCF-4间接影响Wnt信号[21,22]. 由此可见, PC的分化成熟直接或间接地依赖于Wnt通路.

Notch信号通路在调节ISC和祖细胞的增殖和分化, 促进向吸收性细胞而非分泌性细胞的分化中发挥重要的作用. Notch受体及其配体属于Delta/Serrate/Lag-2(DSL)家族, 与Wnt信号传导不同, Notch信号是通过相邻细胞表面的Notch配体(表1)与受体相互作用进行传导[23]. 有实验证明给予Notch通路抑制剂DBZ的Lgr5-GFP小鼠发生CBC凋亡和类器官萌生的效率降低, 且肠道隐窝中出现共表达杯状细胞和PC标志物的"中间细胞", 超微结构分析发现DBZ处理后肠道缺乏正常的具有分泌颗粒的PC, 表明Notch信号可能在决定祖细胞是向杯状细胞还是PC分化和维持成熟PC的分化状态中发挥重要的作用, 但具体的机制尚不明确[24]. 关于Notch信号通路是如何影响祖细胞分化方向的, VanDussen等[24]认为Notch信号通过抑制Atoh1表达来诱导CBC分化为吸收性肠上皮细胞, 但Jensen等发现[25]HES-1-/-小鼠分泌粘液, 和肠内分泌细胞的数量均增加, 但肠上皮细胞数量却减少, 并通过对编码bHLH转录激活因子的RT-PCR分析证明Notch-HES1通路抑制Math-1的表达而影响CBC分化方向. 通过对可表达Notch受体的Tcf-4-/-小鼠的研究, 发现在Tcf-4-/-和Notch激活情况下, 小鼠出生时死亡, 隐窝区域没有发生任何分裂增殖, 但仅Tcf-4-/-时不影响杯状细胞的分化, 表明Notch信号对杯状细胞分化的影响与Wnt信号无关, 而隐窝的增殖依赖于Notch/Wnt/Tcf4共同作用[26]. 鉴于Notch和Wnt信号通路之间存在相互作用, 使得肠上皮细胞分化成熟的作用机制繁杂, 因此有待进一步的研究.

成熟PC顶端有丰富的嗜酸性颗粒, 通过免疫组化实验发现其中包含由PC分泌的多种抗菌肽(antimicrobial peptides, AMP): α-防御素(α-defense)、溶菌酶C(lysozyme C)、胰蛋白酶、再生胰岛衍生蛋白3α(REG3α)、人分泌型磷脂酶A2(Phospholipase A2, sPLA2)以及与宿主防御相关的RNases, 如小鼠血管生成素(Angiopoietin 4, Ang4)等. 这些AMP和PC分泌的细胞因子IL17[33]、TNF[34]共同作用, 调节肠道微生物稳态和免疫应答, 维持肠道微环境的稳态.

在AMP中最引人关注的是α-防御素, 在人类和其他哺乳动物的PC和中性粒细胞中高表达, 在小鼠中被称为隐蛋白肽(cryptdins)[35]. 人PC分泌的α-防御素主要有两种: HD-5和HD-6[36]. HD-5是富含半胱氨酸的阳离子肽, 可与带负电荷的细菌细胞膜结合, 像"打孔"一样以二聚体形式插入细胞膜形成跨膜的离子通道, 增加细胞膜通透性, 使细菌内容物流出而死亡[37], 对革兰阳性菌的抵抗作用要强于革兰阴性菌[36,38]. 有研究发现HD-5转基因小鼠对鼠伤寒沙门氏菌产生明显抗性, 从而证明了HD-5不仅可维持正常肠道菌群的组成, 又可保护肠道菌群不受入侵者的侵袭[39,40]. 与HD-5的直接抗菌作用不同, HD-6不直接杀死细菌, 而是与细菌表面蛋白结合, 经相应配体识别后发生自组装并形成围绕和缠结细菌的纤维网格结构, 抑制细菌的运动而发挥保护肠道作用[41].

在PC中, 人HD-5以未成熟形式储存在分泌颗粒中, 分泌后需经过水解才具有活性[42].但水解过程在小鼠和人之间存在显著差异: 小鼠PC可表达一种蛋白酶-基质金属蛋白酶(matrix metalloproteinase 7, MMP-7), 不仅对HD-5水解过程至关重要, 而且其裂解位点的突变会影响翻译后加工, 产生cryptdins 1/2/3/5/6等多态同工型[43]; 而人PC中未检测到MMP-7[43], 但通过将体外重组未成熟HD-5与牛胰蛋白酶孵育, 对产物进行AU-PAGE和质谱分析, 鉴定产物为成熟HD-5, 从而提出了参与人类HD-5蛋白质加工的酶可能是丝氨酸蛋白酶[44]. 进一步研究发现未成熟HD-5与回肠组织来源的纯化胰蛋白酶在体外孵育后可被水解为成熟HD-5, 体内则发现胰蛋白酶与HD5共存在于人末端回肠隐窝底部的PC中, 推测胰蛋白酶可能参与了未成熟HD-5的水解加工过程[44]. 经过水解成熟的HD-5具有较强抗菌活性, 但未成熟HD-5也具有一定抗菌活性, 尤其是针对李斯特菌, 两者抗菌活性的差异提示: 蛋白水解过程可能是使单一基因产物的抗菌活性多样化的一种机制[44].

除了α-防御素, 首个被发现在PC中表达的AMP-lysozyme C是一种专门水解肽聚糖的糖苷酶[45], 不同于人类只有一种编码lysozyme C的基因, 小鼠中有两种基因分别编码lysozyme P和lysozyme M, 在PC和白细胞中选择性表达.通过对LysM-/-小鼠的研究发现lysozyme M可抑制肽聚糖在组织中积累, 从而避免细菌细胞壁抗原持续存在而导致慢性炎症反应[46], 猜测lysozyme P在肠道组织可能发挥同样作用, 但有待进一步研究证实. 另外, PC还可分泌REG3α、sPLA2和Ang4等. 人源REG3α和鼠源REG3γ45可通过Toll样受体(toll-like receptor, TLR)在PC中被大量诱导表达[47-50], 经胰蛋白酶加工成熟后激活结合肽聚糖的能力,与细菌细胞壁的肽聚糖结合, 发挥抗菌作用[48,51,52]; sPLA2可催化细菌细胞膜磷脂酰乙醇胺和磷脂酰甘油的甘油骨架sn-2处的酯键断裂从而发挥抗菌作用, 尤其针对革兰阳性菌[53-55]; 小鼠Ang4属于具有抗菌和抗病毒活性的RNase亚家族[56], 除具有核糖核酸溶解活性及抗菌作用外[57], 还具有取决于核糖核酸溶解活性的血管生成活性, 该功能或可解释无菌成年小鼠已停止发育的肠道绒毛毛细血管网络在细菌定殖后可被重新启动, 继续发育[58,59], 或许也可为今后心血管疾病研究提供一些新思路.

肠上皮细胞的不断更新对于肠道健康是不可或缺的, 而ISC在其中扮演了至关重要的角色. ISC的稳态、增殖和分化需要受到多种细胞、因子和信号通路的共同调节, 如Notch、Wnt、BMP、EPH/ephrin、Hippo、Hedgehog等信号通路[60], 其中PC作为Lgr5+CBC的"邻居"发挥了重要作用, 隐窝PC缺失的Gfi1-/-、CR2-tox176、Sox9-/-小鼠CBC的数目也会减少[7]. 此外, 有研究从单个Lgr5hiCBC的短期和长期克隆追踪数据发现CBC每隔24小时进行对称分裂使其数量翻倍, 其子细胞争夺"生存空间"[61], 故CBC总是穿插在PC之间, 尽可能增加与PC的接触面积[7].

除PC分泌的AMP对维持CBC生长发育的环境发挥作用外, 基因表达谱分析还显示PC可产生大量表皮细胞生长因子(epidermal growth factor, EGF)、TGF-α、Wnt3和Notch配体Dll4等[7]关键因子来维持CBC稳态. 后来也有研究发现PC还可分泌Notch配体Dll1, 与ISC上的Notch受体Notch1和Notch2结合, 调节ISC增殖分化[32]. 尽管PC来源的Wnt3对于体外肠类器官的培养是必不可少的, 但对于维持肠道稳态却显得不是那么重要, 因为间充质来源的Wnt配体可以进行补充[62,63]. 在Wnt介导的ISC增殖分化中, Lgr4/5配体R-spondin可作为Wnt激动剂, 通过LGR依赖性机制增强Wnt信号传导[64], 但也有研究认为R-spondin不仅发挥了激动作用, 而且与Wnt一起协调PC增殖, 当其缺乏时Wnt无法单独诱导ISC自我更新和体内扩增[63,65]. EGF是体外类器官培养的必要组成成分, Basak等[22,66]通过PathScan阵列分析发现EGF是经MAPK/ERK信号通路调控ISC的增殖和肠道的生长, 抑制EGF受体功能不利于肠道隐窝受损后的恢复, 且发现在类器官中阻断EGF或MAPK信号通路会导致ISC的增殖受到抑制并诱导向肠内分泌细胞系的分化. 但PC不足以提供ISC增殖所需的全部EGF, 最近已有研究表明肠成纤维细胞来源的细胞外囊泡中携带EGF家族成员, 如双调蛋白(amphiregulin), 对于维持ISC生态位发挥重要作用[67].

近年来研究发现受食物热量限制的小鼠PC中mTORC1信号传导受抑制, 进而使Bst1表达增加, 表达产物Bst1可作为一种胞外酶将NAD+转化为环状ADP核糖(cyclic ADP ribose, cADPR), cADPR是一种旁分泌因子, 可通过核苷转运蛋白进入ISC以激活钙信号传导并促进ISC增殖[68]; PC还可通过糖酵解提供乳酸给邻近的Lgr5+CBC, 维持Lgr5+CBC增强的线粒体氧化磷酸化, 进而通过线粒体来源的ROS信号激活p38MAPK活化, 促进Lgr5+CBC的分化[69]. 此外, L-精氨酸可以使PC分泌的Wnt3a增加, 进而通过Wnt3a激活的途径间接刺激ISC增殖[70] .

除了充当肠道菌群调节剂和维持干细胞生态位, PC还可以作为静态干细胞库参与上皮损伤后修复. Yu等人[71]通过给Lyz1-/-小鼠全身进行γ辐照, 发现辐照激活了Notch途径, 导致Notch靶基因Hes1, Ift74, Dtx4, Creb1和Adam17的mRNA水平显着增加并在PC中表达NICD(Notch intracellular domain), 诱导成熟PC去分化, 获得Axin2, Lgr5, Ascl2, Olfm4干细胞样转录组, 拥有短暂增殖和再分化能力来修复损伤组织[71], 该作用对于肠道的炎性损伤具有非常重要的意义. 另有研究发现小鼠在DSS诱导的小肠急性炎症之后Lgr5+CBC急剧减少, 但成熟的PC则可通过SCF/c-Kit信号轴的激活诱导重新进入细胞周期, 通过PI3K/Akt激活和GSK3β抑制作用来增强Wnt途径, 获得干细胞样特性促进组织再生, 从而有助于修复受损的肠组织并使其再生[72]. 由于Hes1是Wnt信号通路靶基因, Notch1是Wnt途径的激活剂[73]以及GSK3β抑制的多效性作用, 故猜测PC在去分化过程中可能存在多种信号传导途径的激活与协同作用[72]. 由此可见, 对于PC细胞的研究有助于对一些疾病的治疗提供新的思路和靶点.

肠道健康不仅仅是我们肉眼所见的没有疾病存在, 还应包括肠道的结构和功能的正常, 具有细长绒毛和短隐窝以及固有黏膜层中有数量丰富的炎症细胞, 具有含较高浓度的抗菌肽、抗体和消化酶的保护屏障-黏液层, 且肠道微生物群落保持生态平衡, 具有种类多样性和功能多样性.而如今包括炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)、结直肠癌等在内的肠道健康问题引起医护人员高度关注, 已有不少研究表明PC与这些威胁肠道健康的消化道疾病密切相关.

有研究认为IBD作为一种免疫介导的疾病, 可累及各段消化道的非特异性、容易反复发作的肠道炎症性疾病. 作为IBD的其中一种, 溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)是结肠黏膜层和黏膜下层连续性炎症, 疾病主要局限于结肠和直肠[74,75], 属于结直肠癌的癌前病变[76]. UC发病高峰年龄为20-49岁, 预计中国已有近58万患者, 而UC的发病机理, 现猜测与PC化生(paneth cells metaplastic, PCM)有关[77,78]. 最新研究发现[79], UC患者化生的PC在异位分泌溶菌酶, 溶菌酶含量增加一方面可增强肠道抗菌作用, 但另一方面也会加剧炎症反应, 导致UC发生.

同样属于IBD的克罗恩病(Crohn's disease, CD)可累及全消化道, 为非连续性全层炎症, 最常累及部位为末端回肠、结肠和肛周[74,75]. CD发病高峰年龄为18-35岁, 预计中国已有近17万患者. 腹痛、腹泻是其最常见的症状, 严重时会有肠梗阻、肠穿孔, 甚至癌变发生.关于其发病机理, 目前普遍认为是由基因与微环境相互作用所引起[80]. 最早鉴定出的CD易感基因之一是与免疫应答相关的Nod2, 其表达产物主要位于PC[81], 可识别结合细菌胞壁酰二肽介导免疫应答[82]. Nod2-/-小鼠PC中的cryptdins水平降低且杀灭肝螺杆菌和李斯特菌能力下降[83,84]. 此外, 还有基因可影响正常Wnt通路从而减少α-defense的表达而引起CD[35,85], 如TCF7L2编码产物Tcf-4蛋白在Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf-4信号通路中可作为转录因子控制MMP-7和α-defense的表达[86], 突变后会导致HD-5和HD-6的表达降低增加患病风险[87]. 还有一些基因与PC分泌途径的功能障碍有关, 这些缺陷可能导致AMP表达降低或其他免疫异常, 从而增加CD的风险. 如Kcnn4[88], 编码钙激活通道KCa3.1, 其活性降低会减少PC颗粒的分泌、α-defense释放[89]; 编码内质网应激反应的关键成分的Xbp1对于PC是必不可少的, 研究发现Xbp1-/-的小鼠出现内质网应激, 进入内质网的未折叠蛋白量与内质网加工蛋白质的能力失衡, 导致蛋白质合成速度减慢, 诱发细胞凋亡、焦亡、自噬[90]. 和自噬相关的ATG16L1与CD的发生也是密切相关[91,92], C57小鼠ATG16L1-/-突变将导致PC分泌颗粒减少[93]. 除了上述基因对于CD发生的影响外, 肠道微环境因素也可通过影响PC的功能进而增加CD发病风险, 如吸烟所致的AMP生成减少[94,95]、急性抗生素治疗降低PC溶菌酶和Reg3g的蛋白质水平以及HD-5的mRNA水平[96]、维生素D缺乏所引起的肠道共生菌群紊乱等[97,98], 另外, 微生物[99]甚至病毒[100]与PC之间的相互作用对于CD发生也是至关重要的.

随着饮食习惯改变、生活节奏加快, 结直肠癌(colorectal cancer cell, CRC)的死亡率升高且出现年轻化, 引起广大医务工作者关注. 并有不少研究表明CRC与PCM相关, 早在1967年就已发现结肠肿瘤中存在PC[101]且在后续研究中PC检测率从0.2%到39%不等[1]. 有研究发现结肠肿瘤细胞包含大量的异型PC和杯状细胞, 还发现了一种既含PC颗粒又含嗜碱性粘蛋白"混合"的Paneth杯状细胞, 提示可能是结肠干细胞分化不良的一种反映, 与细胞快速更新有关[3]. 随着研究不断深入, Wada等[102]从K-ras突变频率和微卫星标记杂合性丧失的角度研究了PCM对右结肠黏膜的影响. 结果显示PCM区域K-ras突变频率明显高于正常组织, 微卫星标记杂合性丧失的标记物LOH-MS检出率明显高于空白对照组, 提示PCM区域存在与CRC相关的基因异常, 从而认为PCM是结肠粘膜癌变的原因之一[102-105].

Wnt信号通路与CRC的发生是密切相关的. 通过对CRC细胞的研究, 发现作为β-catenin/TCF-4所驱动的靶基因c-Myc可以直接抑制p21CIP1/WAF1启动子, 从而阻断了细胞周期抑制剂p21CIP1/WAF1的表达, 导致CRC细胞异常增殖[17]. 有报道80%以上的散发性CRC都出现了APC突变, APC突变可通过抑制β-catenin被蛋白酶体降解间接促进Wnt信号通路的激活[106]. 此外, 一些与Wnt受体相关基因Rnf43和Znrf3的突变也与肿瘤的发生相关. 通过原位杂交和RT-PCR发现CBC细胞可表达Rnf43和Znrf3, 而流式细胞分析证实Rnf43和Znrf3的表达产物可使FZD泛素化, 通过减少CBC细胞膜表面FZD数量而抑制Wnt信号传导, 发生突变时则使Wnt信号通路过度激活从而引发肿瘤, 可能与Apc突变致癌机制不同, Rnf43、Znrf3突变引起的肿瘤依赖于Wnt信号[107]. 总之, Wnt信号通路激活受多种因素和环节的影响, 研究证实高脂、低钙、低维生素D3喂养的小鼠PC发生了异位表达, 而Fzd5、EphB2的表达升高, Wnt信号通路增强, 与散发性肠癌有一定相关性[108].

上述提到的这些研究中可以为治疗或诊断IBD、CRC等消化道疾病以及评估肠道肿瘤的风险提供一些思路和方法, 但对于IBD、CRC的病因和治疗方法依然所知有限, 尤其是相关分子机制的研究, 或许可以成为未来的研究方向.

综上所述, 潘氏细胞并非只是一种位于小肠隐窝底部的分泌性细胞如此简单, 它在肠道健康与平衡中发挥的作用是不可小觑的, 是肠道健康的"守卫者". PC是在肠道干细胞在多种信号的作用下分化而来的, 可以分泌多种抗菌肽和因子以维持肠道干细胞的稳态、调控干细胞的增殖分化, 在调节肠道稳态与免疫反应中发挥重要作用.当肠道上皮受到损伤时, PC又可以化身为静态干细胞库, 参与肠道上皮损伤后的再生.由此可见, 对于PC的研究为IBD和CRC的发生与治疗提供新的靶点.

学科分类: 胃肠病学和肝病学

手稿来源地: 北京市

同行评议报告学术质量分类

A级 (优秀): 0

B级 (非常好): B

C级 (良好): C, C

D级 (一般): D

E级 (差): 0

科学编辑: 张砚梁 制作编辑:张砚梁

| 1. | Singh R, Balasubramanian I, Zhang L, Gao N. Metaplastic Paneth Cells in Extra-Intestinal Mucosal Niche Indicate a Link to Microbiome and Inflammation. Front Physiol. 2020;11:280. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Clevers HC, Bevins CL. Paneth cells: maestros of the small intestinal crypts. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:289-311. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Shousha S. Paneth cell-rich papillary adenocarcinoma and a mucoid adenocarcinoma occurring synchronously in colon: a light and electron microscopic study. Histopathology. 1979;3:489-501. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Mallow EB, Harris A, Salzman N, Russell JP, DeBerardinis RJ, Ruchelli E, Bevins CL. Human enteric defensins. Gene structure and developmental expression. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:4038-4045. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J, Kujala P, van den Born M, Cozijnsen M, Haegebarth A, Korving J, Begthel H, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature. 2007;449:1003-1007. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, Stange DE, Vries RG, van den Born M, Barker N, Shroyer NF, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. Paneth cells constitute the niche for Lgr5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature. 2011;469:415-418. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Li L, Clevers H. Coexistence of quiescent and active adult stem cells in mammals. Science. 2010;327:542-545. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Scoville DH, Sato T, He XC, Li L. Current view: intestinal stem cells and signaling. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:849-864. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Behrens J, von Kries JP, Kühl M, Bruhn L, Wedlich D, Grosschedl R, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of beta-catenin with the transcription factor LEF-1. Nature. 1996;382:638-642. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destrée O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell. 1996;86:391-399. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Behrens J, Jerchow BA, Würtele M, Grimm J, Asbrand C, Wirtz R, Kühl M, Wedlich D, Birchmeier W. Functional interaction of an axin homolog, conductin, with beta-catenin, APC, and GSK3beta. Science. 1998;280:596-599. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Gracz AD, Magness ST. Defining hierarchies of stemness in the intestine: evidence from biomarkers and regulatory pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2014;307:G260-G273. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, van Donselaar E, Huls G, Peters PJ, Clevers H. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet. 1998;19:379-383. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Silberg DG, Swain GP, Suh ER, Traber PG. Cdx1 and cdx2 expression during intestinal development. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:961-971. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Yang Q, Bermingham NA, Finegold MJ, Zoghbi HY. Requirement of Math1 for secretory cell lineage commitment in the mouse intestine. Science. 2001;294:2155-2158. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | van de Wetering M, Sancho E, Verweij C, de Lau W, Oving I, Hurlstone A, van der Horn K, Batlle E, Coudreuse D, Haramis AP, Tjon-Pon-Fong M, Moerer P, van den Born M, Soete G, Pals S, Eilers M, Medema R, Clevers H. The beta-catenin/TCF-4 complex imposes a crypt progenitor phenotype on colorectal cancer cells. Cell. 2002;111:241-250. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Blache P, van de Wetering M, Duluc I, Domon C, Berta P, Freund JN, Clevers H, Jay P. SOX9 is an intestine crypt transcription factor, is regulated by the Wnt pathway, and represses the CDX2 and MUC2 genes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:37-47. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Batlle E, Henderson JT, Beghtel H, van den Born MM, Sancho E, Huls G, Meeldijk J, Robertson J, van de Wetering M, Pawson T, Clevers H. Beta-catenin and TCF mediate cell positioning in the intestinal epithelium by controlling the expression of EphB/ephrinB. Cell. 2002;111:251-263. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Stappenbeck TS, Gordon JI. Rac1 mutations produce aberrant epithelial differentiation in the developing and adult mouse small intestine. Development. 2000;127:2629-2642. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kabiri Z, Greicius G, Zaribafzadeh H, Hemmerich A, Counter CM, Virshup DM. Wnt signaling suppresses MAPK-driven proliferation of intestinal stem cells. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:3806-3812. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Cray P, Sheahan BJ, Dekaney CM. Secretory Sorcery: Paneth Cell Control of Intestinal Repair and Homeostasis. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Noah TK, Shroyer NF. Notch in the intestine: regulation of homeostasis and pathogenesis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2013;75:263-288. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | VanDussen KL, Carulli AJ, Keeley TM, Patel SR, Puthoff BJ, Magness ST, Tran IT, Maillard I, Siebel C, Kolterud Å, Grosse AS, Gumucio DL, Ernst SA, Tsai YH, Dempsey PJ, Samuelson LC. Notch signaling modulates proliferation and differentiation of intestinal crypt base columnar stem cells. Development. 2012;139:488-497. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Jensen J, Pedersen EE, Galante P, Hald J, Heller RS, Ishibashi M, Kageyama R, Guillemot F, Serup P, Madsen OD. Control of endodermal endocrine development by Hes-1. Nat Genet. 2000;24:36-44. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Fre S, Pallavi SK, Huyghe M, Laé M, Janssen KP, Robine S, Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Louvard D. Notch and Wnt signals cooperatively control cell proliferation and tumorigenesis in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:6309-6314. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Roelink H, Nusse R. Expression of two members of the Wnt family during mouse development--restricted temporal and spatial patterns in the developing neural tube. Genes Dev. 1991;5:381-388. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Gregorieff A, Pinto D, Begthel H, Destrée O, Kielman M, Clevers H. Expression pattern of Wnt signaling components in the adult intestine. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:626-638. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Gavin BJ, McMahon JA, McMahon AP. Expression of multiple novel Wnt-1/int-1-related genes during fetal and adult mouse development. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2319-2332. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Topol L, Jiang X, Choi H, Garrett-Beal L, Carolan PJ, Yang Y. Wnt-5a inhibits the canonical Wnt pathway by promoting GSK-3-independent beta-catenin degradation. J Cell Biol. 2003;162:899-908. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Schröder N, Gossler A. Expression of Notch pathway components in fetal and adult mouse small intestine. Gene Expr Patterns. 2002;2:247-250. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Carulli AJ, Keeley TM, Demitrack ES, Chung J, Maillard I, Samuelson LC. Notch receptor regulation of intestinal stem cell homeostasis and crypt regeneration. Dev Biol. 2015;402:98-108. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Takahashi N, Vanlaere I, de Rycke R, Cauwels A, Joosten LA, Lubberts E, van den Berg WB, Libert C. IL-17 produced by Paneth cells drives TNF-induced shock. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1755-1761. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Tan X, Hsueh W, Gonzalez-Crussi F. Cellular localization of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha transcripts in normal bowel and in necrotizing enterocolitis. TNF gene expression by Paneth cells, intestinal eosinophils, and macrophages. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1858-1865. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Ganz T. Defensins: antimicrobial peptides of innate immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:710-720. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Bevins CL, Salzman NH. Paneth cells, antimicrobial peptides and maintenance of intestinal homeostasis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;9:356-368. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Hemshekhar M, Anaparti V, Mookherjee N. Functions of Cationic Host Defense Peptides in Immunity. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2016;9. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Wanniarachchi YA, Kaczmarek P, Wan A, Nolan EM. Human defensin 5 disulfide array mutants: disulfide bond deletion attenuates antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus. Biochemistry. 2011;50:8005-8017. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Salzman NH, Hung K, Haribhai D, Chu H, Karlsson-Sjöberg J, Amir E, Teggatz P, Barman M, Hayward M, Eastwood D, Stoel M, Zhou Y, Sodergren E, Weinstock GM, Bevins CL, Williams CB, Bos NA. Enteric defensins are essential regulators of intestinal microbial ecology. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:76-83. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Salzman NH, Ghosh D, Huttner KM, Paterson Y, Bevins CL. Protection against enteric salmonellosis in transgenic mice expressing a human intestinal defensin. Nature. 2003;422:522-526. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Chu H, Pazgier M, Jung G, Nuccio SP, Castillo PA, de Jong MF, Winter MG, Winter SE, Wehkamp J, Shen B, Salzman NH, Underwood MA, Tsolis RM, Young GM, Lu W, Lehrer RI, Bäumler AJ, Bevins CL. Human α-defensin 6 promotes mucosal innate immunity through self-assembled peptide nanonets. Science. 2012;337:477-481. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Cunliffe RN, Rose FR, Keyte J, Abberley L, Chan WC, Mahida YR. Human defensin 5 is stored in precursor form in normal Paneth cells and is expressed by some villous epithelial cells and by metaplastic Paneth cells in the colon in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2001;48:176-185. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | Wilson CL, Ouellette AJ, Satchell DP, Ayabe T, López-Boado YS, Stratman JL, Hultgren SJ, Matrisian LM, Parks WC. Regulation of intestinal alpha-defensin activation by the metalloproteinase matrilysin in innate host defense. Science. 1999;286:113-117. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | Ghosh D, Porter E, Shen B, Lee SK, Wilk D, Drazba J, Yadav SP, Crabb JW, Ganz T, Bevins CL. Paneth cell trypsin is the processing enzyme for human defensin-5. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:583-590. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Porter EM, Bevins CL, Ghosh D, Ganz T. The multifaceted Paneth cell. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:156-170. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Ganz T, Gabayan V, Liao HI, Liu L, Oren A, Graf T, Cole AM. Increased inflammation in lysozyme M-deficient mice in response to Micrococcus luteus and its peptidoglycan. Blood. 2003;101:2388-2392. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Christa L, Carnot F, Simon MT, Levavasseur F, Stinnakre MG, Lasserre C, Thepot D, Clement B, Devinoy E, Brechot C. HIP/PAP is an adhesive protein expressed in hepatocarcinoma, normal Paneth, and pancreatic cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:G993-1002. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Cash HL, Whitham CV, Behrendt CL, Hooper LV. Symbiotic bacteria direct expression of an intestinal bactericidal lectin. Science. 2006;313:1126-1130. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Vaishnava S, Behrendt CL, Ismail AS, Eckmann L, Hooper LV. Paneth cells directly sense gut commensals and maintain homeostasis at the intestinal host-microbial interface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20858-20863. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Lasserre C, Colnot C, Bréchot C, Poirier F. HIP/PAP gene, encoding a C-type lectin overexpressed in primary liver cancer, is expressed in nervous system as well as in intestine and pancreas of the postimplantation mouse embryo. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1601-1610. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Medveczky P, Szmola R, Sahin-Tóth M. Proteolytic activation of human pancreatitis-associated protein is required for peptidoglycan binding and bacterial aggregation. Biochem J. 2009;420:335-343. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | Mukherjee S, Partch CL, Lehotzky RE, Whitham CV, Chu H, Bevins CL, Gardner KH, Hooper LV. Regulation of C-type lectin antimicrobial activity by a flexible N-terminal prosegment. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:4881-4888. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 53. | Murakami M, Taketomi Y, Girard C, Yamamoto K, Lambeau G. Emerging roles of secreted phospholipase A2 enzymes: Lessons from transgenic and knockout mice. Biochimie. 2010;92:561-582. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | Nevalainen TJ, Graham GG, Scott KF. Antibacterial actions of secreted phospholipases A2. Review. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1781:1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 55. | Lambeau G, Gelb MH. Biochemistry and physiology of mammalian secreted phospholipases A2. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:495-520. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 56. | Harder J, Schroder JM. RNase 7, a novel innate immune defense antimicrobial protein of healthy human skin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:46779-46784. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 57. | Hooper LV, Stappenbeck TS, Hong CV, Gordon JI. Angiogenins: a new class of microbicidal proteins involved in innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:269-273. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 58. | Crabtree B, Holloway DE, Baker MD, Acharya KR, Subramanian V. Biological and structural features of murine angiogenin-4, an angiogenic protein. Biochemistry. 2007;46:2431-2443. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 59. | Stappenbeck TS, Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Developmental regulation of intestinal angiogenesis by indigenous microbes via Paneth cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15451-15455. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 60. | Meran L, Baulies A, Li VSW. Intestinal Stem Cell Niche: The Extracellular Matrix and Cellular Components. Stem Cells Int. 2017;2017:7970385. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 61. | Cheng H, Merzel J, Leblond CP. Renewal of Paneth cells in the small intestine of the mouse. Am J Anat. 1969;126:507-525. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 62. | Kabiri Z, Greicius G, Madan B, Biechele S, Zhong Z, Zaribafzadeh H, Edison, Aliyev J, Wu Y, Bunte R, Williams BO, Rossant J, Virshup DM. Stroma provides an intestinal stem cell niche in the absence of epithelial Wnts. Development. 2014;141:2206-2215. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 63. | Farin HF, Van Es JH, Clevers H. Redundant sources of Wnt regulate intestinal stem cells and promote formation of Paneth cells. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1518-1529.e7. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 64. | de Lau W, Peng WC, Gros P, Clevers H. The R-spondin/Lgr5/Rnf43 module: regulator of Wnt signal strength. Genes Dev. 2014;28:305-316. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 65. | Yan KS, Janda CY, Chang J, Zheng GXY, Larkin KA, Luca VC, Chia LA, Mah AT, Han A, Terry JM, Ootani A, Roelf K, Lee M, Yuan J, Li X, Bolen CR, Wilhelmy J, Davies PS, Ueno H, von Furstenberg RJ, Belgrader P, Ziraldo SB, Ordonez H, Henning SJ, Wong MH, Snyder MP, Weissman IL, Hsueh AJ, Mikkelsen TS, Garcia KC, Kuo CJ. Non-equivalence of Wnt and R-spondin ligands during Lgr5+ intestinal stem-cell self-renewal. Nature. 2017;545:238-242. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 66. | Basak O, Beumer J, Wiebrands K, Seno H, van Oudenaarden A, Clevers H. Induced Quiescence of Lgr5+ Stem Cells in Intestinal Organoids Enables Differentiation of Hormone-Producing Enteroendocrine Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;20:177-190.e4. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 67. | Oszvald Á, Szvicsek Z, Sándor GO, Kelemen A, Soós AÁ, Pálóczi K, Bursics A, Dede K, Tölgyes T, Buzás EI, Zeöld A, Wiener Z. Extracellular vesicles transmit epithelial growth factor activity in the intestinal stem cell niche. Stem Cells. 2020;38:291-300. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 68. | Yilmaz ÖH, Katajisto P, Lamming DW, Gültekin Y, Bauer-Rowe KE, Sengupta S, Birsoy K, Dursun A, Yilmaz VO, Selig M, Nielsen GP, Mino-Kenudson M, Zukerberg LR, Bhan AK, Deshpande V, Sabatini DM. mTORC1 in the Paneth cell niche couples intestinal stem-cell function to calorie intake. Nature. 2012;486:490-495. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 69. | Rodríguez-Colman MJ, Schewe M, Meerlo M, Stigter E, Gerrits J, Pras-Raves M, Sacchetti A, Hornsveld M, Oost KC, Snippert HJ, Verhoeven-Duif N, Fodde R, Burgering BM. Interplay between metabolic identities in the intestinal crypt supports stem cell function. Nature. 2017;543:424-427. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 70. | Hou Q, Dong Y, Yu Q, Wang B, Le S, Guo Y, Zhang B. Regulation of the Paneth cell niche by exogenous L-arginine couples the intestinal stem cell function. FASEB J. 2020;34:10299-10315. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 71. | Yu S, Tong K, Zhao Y, Balasubramanian I, Yap GS, Ferraris RP, Bonder EM, Verzi MP, Gao N. Paneth Cell Multipotency Induced by Notch Activation following Injury. Cell Stem Cell. 2018;23:46-59.e5. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 72. | Schmitt M, Schewe M, Sacchetti A, Feijtel D, van de Geer WS, Teeuwssen M, Sleddens HF, Joosten R, van Royen ME, van de Werken HJG, van Es J, Clevers H, Fodde R. Paneth Cells Respond to Inflammation and Contribute to Tissue Regeneration by Acquiring Stem-like Features through SCF/c-Kit Signaling. Cell Rep. 2018;24:2312-2328.e7. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 73. | Collu GM, Hidalgo-Sastre A, Brennan K. Wnt-Notch signalling crosstalk in development and disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:3553-3567. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 74. | 赵 锐, 周 勇. 溃疡性结肠炎的手术指征, 手术方式及围手术期管理. 中华结直肠疾病电子杂志. 2020;9:82-85. |

| 75. | Baumgart M, Dogan B, Rishniw M, Weitzman G, Bosworth B, Yantiss R, Orsi RH, Wiedmann M, McDonough, P, Kim SG, Berg D, Schukken Y, Scherl E, Simpson KW. Culture independent analysis of ileal mucosa reveals a selective increase in invasive Escherichia coli of novel phylogeny relative to depletion of Clostridiales in Crohn's disease involving the ileum. ISME J. 2007;1:403-418. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 76. | Rutter MD, Saunders BP, Wilkinson KH, Rumbles S, Schofield G, Kamm MA, Williams CB, Price AB, Talbot IC, Forbes A. Cancer surveillance in longstanding ulcerative colitis: endoscopic appearances help predict cancer risk. Gut. 2004;53:1813-1816. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 77. | Tanaka M, Saito H, Kusumi T, Fukuda S, Shimoyama T, Sasaki Y, Suto K, Munakata A, Kudo H. Spatial distribution and histogenesis of colorectal Paneth cell metaplasia in idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2001;16:1353-1359. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 78. | PATERSON JC, WATSON SH. Paneth cell metaplasia in ulcerative colitis. Am J Pathol. 1961;38:243-249. [PubMed] |

| 79. | Yu S, Balasubramanian I, Laubitz D, Tong K, Bandyopadhyay S, Lin X, Flores J, Singh R, Liu Y, Macazana C, Zhao Y, Béguet-Crespel F, Patil K, Midura-Kiela MT, Wang D, Yap GS, Ferraris RP, Wei Z, Bonder EM, Häggblom MM, Zhang L, Douard V, Verzi MP, Cadwell K, Kiela PR, Gao N. Paneth Cell-Derived Lysozyme Defines the Composition of Mucolytic Microbiota and the Inflammatory Tone of the Intestine. Immunity. 2020;53:398-416.e8. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 80. | Jacob N, Jacobs JP, Kumagai K, Ha CWY, Kanazawa Y, Lagishetty V, Altmayer K, Hamill AM, Von Arx A, Sartor RB, Devkota S, Braun J, Michelsen KS, Targan SR, Shih DQ. Inflammation-independent TL1A-mediated intestinal fibrosis is dependent on the gut microbiome. Mucosal Immunol. 2018;11:1466-1476. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 81. | Ogura Y, Lala S, Xin W, Smith E, Dowds TA, Chen FF, Zimmermann E, Tretiakova M, Cho JH, Hart J, Greenson JK, Keshav S, Nuñez G. Expression of NOD2 in Paneth cells: a possible link to Crohn's ileitis. Gut. 2003;52:1591-1597. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 82. | Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, Nicolae DL, Chen FF, Ramos R, Britton H, Moran T, Karaliuskas R, Duerr RH, Achkar JP, Brant SR, Bayless TM, Kirschner BS, Hanauer SB, Nuñez G, Cho JH. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603-606. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 83. | Petnicki-Ocwieja T, Hrncir T, Liu YJ, Biswas A, Hudcovic T, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H, Kobayashi KS. Nod2 is required for the regulation of commensal microbiota in the intestine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:15813-15818. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 84. | Kobayashi KS, Chamaillard M, Ogura Y, Henegariu O, Inohara N, Nuñez G, Flavell RA. Nod2-dependent regulation of innate and adaptive immunity in the intestinal tract. Science. 2005;307:731-734. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 85. | Courth LF, Ostaff MJ, Mailänder-Sánchez D, Malek NP, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Crohn's disease-derived monocytes fail to induce Paneth cell defensins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:14000-14005. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 86. | van Es JH, Jay P, Gregorieff A, van Gijn ME, Jonkheer S, Hatzis P, Thiele A, van den Born M, Begthel H, Brabletz T, Taketo MM, Clevers H. Wnt signalling induces maturation of Paneth cells in intestinal crypts. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:381-386. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 87. | Wehkamp J, Wang G, Kübler I, Nuding S, Gregorieff A, Schnabel A, Kays RJ, Fellermann K, Burk O, Schwab M, Clevers H, Bevins CL, Stange EF. The Paneth cell alpha-defensin deficiency of ileal Crohn's disease is linked to Wnt/Tcf-4. J Immunol. 2007;179:3109-3118. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 88. | Simms LA, Doecke JD, Roberts RL, Fowler EV, Zhao ZZ, McGuckin MA, Huang N, Hayward NK, Webb PM, Whiteman DC, Cavanaugh JA, McCallum R, Florin TH, Barclay ML, Gearry RB, Merriman TR, Montgomery GW, Radford-Smith GL. KCNN4 gene variant is associated with ileal Crohn's Disease in the Australian and New Zealand population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:2209-2217. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 89. | Di L, Srivastava S, Zhdanova O, Ding Y, Li Z, Wulff H, Lafaille M, Skolnik EY. Inhibition of the K+ channel KCa3.1 ameliorates T cell-mediated colitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:1541-1546. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 90. | Kaser A, Lee AH, Franke A, Glickman JN, Zeissig S, Tilg H, Nieuwenhuis EE, Higgins DE, Schreiber S, Glimcher LH, Blumberg RS. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 2008;134:743-756. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 91. | Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, Silverberg MS, Goyette P, Huett A, Green T, Kuballa P, Barmada MM, Datta LW, Shugart YY, Griffiths AM, Targan SR, Ippoliti AF, Bernard EJ, Mei L, Nicolae DL, Regueiro M, Schumm LP, Steinhart AH, Rotter JI, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Daly MJ, Brant SR. Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:596-604. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 92. | Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008;132:27-42. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 93. | Cadwell K, Liu JY, Brown SL, Miyoshi H, Loh J, Lennerz JK, Kishi C, Kc W, Carrero JA, Hunt S, Stone CD, Brunt EM, Xavier RJ, Sleckman BP, Li E, Mizushima N, Stappenbeck TS, Virgin HW 4th. A key role for autophagy and the autophagy gene Atg16l1 in mouse and human intestinal Paneth cells. Nature. 2008;456:259-263. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 94. | Berkowitz L, Pardo-Roa C, Salazar GA, Salazar-Echegarai F, Miranda JP, Ramírez G, Chávez JL, Kalergis AM, Bueno SM, Álvarez-Lobos M. Mucosal Exposure to Cigarette Components Induces Intestinal Inflammation and Alters Antimicrobial Response in Mice. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2289. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 95. | Liu TC, Kern JT, VanDussen KL, Xiong S, Kaiko GE, Wilen CB, Rajala MW, Caruso R, Holtzman MJ, Gao F, McGovern DP, Nunez G, Head RD, Stappenbeck TS. Interaction between smoking and ATG16L1T300A triggers Paneth cell defects in Crohn's disease. J Clin Invest. 2018;128:5110-5122. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 96. | Wang J, Tian F, Wang P, Zheng H, Zhang Y, Tian H, Zhang L, Gao X, Wang X. Gut Microbiota as a Modulator of Paneth Cells During Parenteral Nutrition in Mice. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2018;42:1280-1287. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 97. | Lu R, Zhang YG, Xia Y, Zhang J, Kaser A, Blumberg R, Sun J. Paneth Cell Alertness to Pathogens Maintained by Vitamin D Receptors. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1269-1283. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 98. | Su D, Nie Y, Zhu A, Chen Z, Wu P, Zhang L, Luo M, Sun Q, Cai L, Lai Y, Xiao Z, Duan Z, Zheng S, Wu G, Hu R, Tsukamoto H, Lugea A, Liu Z, Pandol SJ, Han YP. Vitamin D Signaling through Induction of Paneth Cell Defensins Maintains Gut Microbiota and Improves Metabolic Disorders and Hepatic Steatosis in Animal Models. Front Physiol. 2016;7:498. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 99. | Wehkamp J, Schauber J, Stange EF. Defensins and cathelicidins in gastrointestinal infections. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2007;23:32-38. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 100. | Holly MK, Smith JG. Paneth Cells during Viral Infection and Pathogenesis. Viruses. 2018;10. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 101. | Gibbs NM. Incidence and significance of argentaffin and paneth cells in some tumours of the large intestine. J Clin Pathol. 1967;20:826-831. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 102. | Wada R, Yamaguchi T, Tadokoro K. Colonic Paneth cell metaplasia is pre-neoplastic condition of colonic cancer or not? J Carcinog. 2005;4:5. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 103. | Morson B. President's address. The polyp-cancer sequence in the large bowel. Proc R Soc Med. 1974;67:451-457. [PubMed] |

| 104. | Thibodeau SN, Bren G, Schaid D. Microsatellite instability in cancer of the proximal colon. Science. 1993;260:816-819. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 105. | Senba S, Konishi F, Okamoto T, Kashiwagi H, Kanazawa K, Miyaki M, Konishi M, Tsukamoto T. Clinicopathologic and genetic features of nonfamilial colorectal carcinomas with DNA replication errors. Cancer. 1998;82:279-285. [PubMed] |

| 106. | Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Lessons from hereditary colorectal cancer. Cell. 1996;87:159-170. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 107. | Koo BK, Spit M, Jordens I, Low TY, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, van Es JH, Mohammed S, Heck AJ, Maurice MM, Clevers H. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of Wnt receptors. Nature. 2012;488:665-669. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 108. | Wang D, Peregrina K, Dhima E, Lin EY, Mariadason JM, Augenlicht LH. Paneth cell marker expression in intestinal villi and colon crypts characterizes dietary induced risk for mouse sporadic intestinal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:10272-10277. [PubMed] [DOI] |