修回日期: 2017-08-10

接受日期: 2017-08-23

在线出版日期: 2017-10-18

胃肠道动力紊乱是重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU)患者常见的临床并发症, 可导致肠内营养不能实施、呕吐、腹泻、腹腔压力增高、呼吸机相关性肺炎、肠道菌群移位等不良反应. 胃肠道动力紊乱的临床特点主要包括: 胃排空障碍、小肠消化间期肠动力紊乱和消化期动力紊乱. 引起ICU患者胃肠动力紊乱的原因较为复杂以及临床实施胃肠道动力评估颇有困难, 这些因素导致了胃肠动力学监测技术并未在临床广泛推广. 及时发现和纠正ICU患者胃肠道动力紊乱可以改善患者预后. 本文将对ICU患者胃肠动力紊乱的病因、临床评估和治疗进行综述.

核心提要: 危重病患者胃肠道功能紊乱在重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU)中经常发生, 不仅给患者带来身体不适, 而且增加死亡率. 本文综述了胃肠运动的病理生理基础, 病理性运动改变的主要模式, 对患者预后的影响, 以及目前的评估和治疗措施. 预防和及时合理地治疗患者的胃肠功能紊乱将有助于ICU患者的康复, 因此意义重大.

引文著录: 傅小云. 重症患者胃肠动力紊乱: 发病机制、临床评估及治疗. 世界华人消化杂志 2017; 25(29): 2583-2590

Revised: August 10, 2017

Accepted: August 23, 2017

Published online: October 18, 2017

Gastrointestinal motility dysfunction is a common clinical complication in ICU patients, which can lead to difficulty in enteral nutrition, vomiting, diarrhea, increased intra-abdominal pressure, ventilator associated pneumonia, intestinal flora displacement, and other adverse reactions. The clinical features of gastrointestinal dysfunction mainly include gastric emptying disturbance, intestinal dysfunction, and gastrointestinal motility disorders. The causes of gastrointestinal motility dysfunction in ICU patients are complex and the clinical evaluation of gastrointestinal dysfunction is difficult. These factors have led to the fact that gastrointestinal motility monitoring techniques have not been widely used in clinical practice. Timely detection and correction of gastrointestinal motility dysfunction in ICU patients can improve outcomes. This article reviews the etiology, clinical evaluation, and treatment of gastrointestinal motility dysfunction in ICU patients.

- Citation: Fu XY. Gastrointestinal motility dysfunction in critically ill patients: Pathogenesis, clinical assessment, and treatment. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2017; 25(29): 2583-2590

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v25/i29/2583.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v25.i29.2583

重症患者的胃肠道动力紊乱是重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU)患者常见的临床并发症, 但长期以来为重症医师所忽略[1-3]. 重症患者肠动力紊乱可导致肠内营养不能实施、呕吐、腹泻、腹腔压力增高、呼吸机相关性肺炎、肠道菌群移位等不良反应[4-6], 本文对重症患者肠动力紊乱的机制及临床治疗进展作一综述.

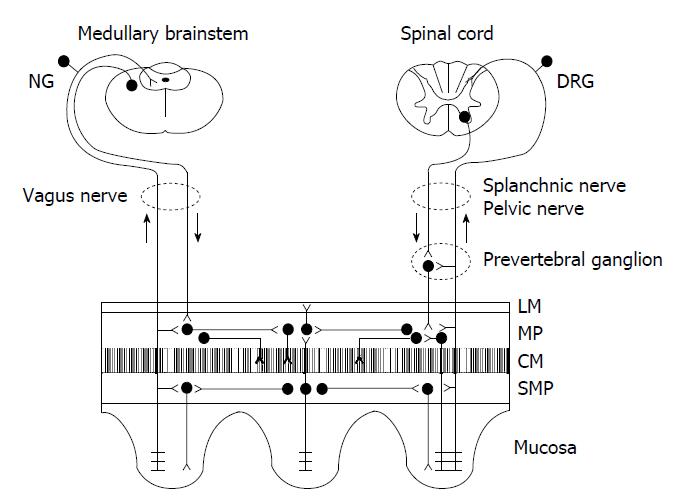

肠道动力的主要功能是混合和推动食物在消化道运行, 使得营养得以吸收, 并清除近端小肠的食物残留及细菌. 胃肠道动力的控制是极其复杂的, 通常受中枢、自主神经、肠神经系统(enteric nervous systems, ENS)调节[7]. 肠神经系统包含胃肠道的黏膜下神经丛(麦斯纳氏神经丛, Meissner's plexus)和肠肌神经丛(奥尔巴克氏神经丛, Auerbach plexus)的神经节细胞、中间连结纤维以及从神经丛发出供应胃肠道平滑肌、腺体和血管的神经纤维(图1)[8]. 人肠壁内的神经节细胞超过1亿个, 约与脊髓内所含神经元的总数相近. 进入肠壁的交感神经节后纤维和副交感神经节前纤维, 只能与部分肠神经节细胞形成突触联系, 传递中枢神经系统的信息, 影响兴奋性或抑制性神经递质的释放, 从而调节胃肠道功能. 还有大量肠神经节细胞并不直接接受来自中枢神经系统的冲动. 肠道动力主要由肠肌神经丛调节, 乙酰胆碱与P物质是构成兴奋型运动神经元的主要递质, 而NO、三磷酸腺苷、血管活性肠肽是抑制型神经元的主要递质(表1).

| 兴奋型递质 | 抑制型递质 |

| 乙酰胆碱 | NO |

| 胆囊收缩素 | 血管活性肠肽 |

| 促胃动素 | γ-氨基丁酸 |

| 5-羟色胺 | 去甲肾上腺素 |

| 前列腺素E2 | 生长抑素 |

| 神经激肽a | 高血糖素 |

| 胃泌素释放肽 | P物质 |

| 铃蟾肽 | 阿片类 |

| 胰泌素 | |

| 三磷酸腺苷 |

ICU重症患者很多疾病均可导致胃肠道动力紊乱, 包括: 腹部外科、头脊髓损伤、全身炎症反应综合征、脓毒症、全身或局部的低灌注、缺氧、电解质紊乱和血糖异常等[9]. 在各种病理条件下, 五羟色胺、NO、儿茶酚胺、降钙素相关肽等神经递质通过复杂的调节通路抑制肠动力. ICU重症患者往往使用大量的药物, 这些药物对重症患者是必须应用而无法或缺, 但却可导致胃肠道动力紊乱. 麻醉镇静药、儿茶酚胺类血管活性药物以及可乐定、右旋美托咪啶等这类α受体激动剂均可导致肠动力减弱[10]. 重症患者液体管理不当以及电解质紊乱也可以导致胃肠动力紊乱, 液体管理对肠动力的影响的研究大都局限在围术期, 有学者发现, 在腹部外科患者术中大量输液与限制性输液[12 mL vs 4 mL/(kg•h)]比较, 大量输液的患者在术后肠动力恢复明显延长[11,12]. 此外, 肠屏障功能与胃肠道微生态破坏也与ICU患者胃肠动力紊乱密切相关[13,14].

胃排空障碍是ICU早期肠内营养失败的主要原因之一[1,15], 且增加误吸的风险和胃内细菌的繁殖. 胃排空损伤机制之一是原始动力功能失常导致胃窦平滑肌动力下降, 即使在摄食期间, 胃动力仍呈消化间期的运动模式; 另外一个原因是肠动力的下降使得近端小肠激活负反馈调节通路进一步使得胃排空收到抑制. 营养物质可促进一些神经内分泌肽的释放, 诸如胆囊收缩素(cholecystokinin, CCK)五羟色胺等物质能激活迷走神经核脊髓的传入神经元从而抑制胃排空. 应激、颅内压增高可抑制胃动力使得排空功能减弱, 高血糖可通过降低迷走神经活性抑制肠肌丛神经NO的释放导致胃排空能力下降[16].

重症患者肠动力紊乱以移行性复合运动(migrating motor complex, MMC)模式紊乱为主要表现. Miedema等[17]报道术后重症患者消化间期的肠运动模式与对照组相比, Ⅰ相运动增加, Ⅱ相运动模式明显减少, Ⅲ相运动频率亦呈增加态势, 而且增加小肠的Ⅲ相运动是逆行的, 这往往导致小肠的转运延迟. 其他的一些研究也得到了相似的结果, 在机械通气患者胃窦部的MMC出现缺失, 而MMC起源于十二指肠同健康志愿者相比, 同样出现Ⅰ相运动增加, Ⅱ相运动受到抑制. MMC的运行也是异常的, 出现逆行或者静止. MMC模式紊乱导致肠腔内容物向结肠流动出现障碍, 肠内容物在肠腔内瘀滞、甚至逆流, 微生物过度生长, 细菌移位, 增加呼吸机相关性肺炎的发生. 研究[18]表明机械性通气也与胃肠动力紊乱相关.

重症患者最常见的一个问题是肠动力从消化间期转向消化期的能力减弱. 尽管营养输送到肠道, 肠道运动却无法转向消化期运动模式, 与Ⅲ相运动相比较, 只是以一种较之幅度频率增加的压力波出现. 这些压力波的频率至少是正常消化运动的两倍. 这种从消化间期运动模式到消化期运动模式转换能力的衰竭可能与重症患者腹泻的发生有关.

在ICU中, 重症患者胃肠动力进行动态监测对早期启动肠内营养有重要意义. 从临床体征看, 恶心、呕吐、腹胀通常提示患者存在肠动力紊乱. 肠鸣音的存在与否, 通常也被认为与肠蠕动是否存在有关, 但并不准确, 2009年肠内营养指南并未把肠鸣音存在与否作为是否启动肠内营养的判断标准, 肠梗阻时肠鸣音可消失、减弱或增强, 在临床上增加了判断的难度. 胃残余量(gastric function voloumes, GRVs)通常用于判断ICU患者胃排空能力, 但受影响的因素也很多, 如: 技术、患者体位、胃管的位置和直径等. ICU患者的胃肠动力评估颇具挑战性, 除了研究目的外, 临床实施颇有困难, 现将目前的一些方法介绍如下.

4.1.1 胃闪烁成像技术: 目前, 放射性同位素闪烁成像是用于评估胃排空能力的"金标准"[19], 可测定固相和液相排空, 是一种非侵入性的且行之有效的方法[20]. 基本方法是将放射性核素标记的药物混匀于食物内, 口服后用带有计算机的γ照相机连续记录胃区的动态图像, 通过胃区放射性标志物的下降的情况, 计算出胃排空时间. ICU重症患者采用此方法受一定限制, 主要是因为检测时间长, 重症患者常需要呼吸支持增加转运的风险. 此外, 带放射性核素标记的食物也许另外配置.

4.1.2 对乙酰氨基酚吸收试验: ICU中, 常用对乙酰氨基酚吸收实验常用于评估胃排空能力, 对乙酰氨基酚在胃不能被吸收, 在小肠可被吸收. 因此, 检测血浆对乙酰氨基酚水平可了解胃排空能力. 但该试验, 受影响因素较多, 小肠吸收功能, 药物的首过效应, 肝功能状态、多次的血液样本检查等均可影响实测试结果, 有研究[21]表明对乙酰氨基酚吸收试验与为残余量检测用于评估ICU持续肠内营养仅有弱相关性. 最近一项研究[22]结果表明对乙酰氨基酚吸收试验可能是筛选胃管排空延迟患者的一个技术手段.

4.1.3 呼吸试验: 呼吸试验可用于液体和固体胃排空能力检测. 目前应用较多的是13C-辛酸呼气试验, 13C-乙酸呼气试验(13C-acetate breath test)在检测胃液体排空比13C-辛酸更灵敏. 近来, 随着对13C-乙酸呼气试验解读方法学的改进, 使得13C-辛酸呼气试验所得胃排空的参数可以与金标准所得的相关参数直接对应起来. 先前的研究[23,24]表明13C-乙酸呼气试验是一种可靠、无创性的液体胃排空率测定方. 但是, 13C-乙酸呼气试验并非直接检测受试者胃排空情况, 这在某种程度上妨碍了其在临床上的广泛应用, 在ICU重症患者可尝试应用, 但多器官功能衰竭患者, 该试验准确性仍受到限制[25].

4.1.4 超声及磁共振成像: 基于特定的算法, 超声可根据其获得的图像数据计算出胃容量, 用于胃排空能力评估. 具体方法是患者摄入检测食物后, 每15 min行超声检测1次, 计算胃超声下横断面积的变化. 该方法无创, 操作简单, 但须有经验的超声医师操作, 检测时间长. 肥胖的患者也不是很适合, 因为在评估图像上存在技术困难. 目前, 有报道利用三维超声评价胃排空功能[26], 虽然三维超声在体积计算方面有着明显优势, 但对设备要求较高, 从而限制了其在临床的广泛应用[27,28]. 超声用于重症患者胃排空评估目前尚鲜有研究. 磁共振成像也可用于胃排空的评估, 作为一种新方法, 磁共振成像用于评估胃动力是一种精确的方法[29,30], 可用于作为评估胃动力的标准工具, 但重症患者用磁共振成像评估胃动力, 存在花费较高, 转运困难的限制.

4.1.5 胃电图: 胃肠道平滑肌的基本生理功能是通过兴奋-收缩偶联, 产生胃肠道的各种形式运动, 胃肠道平滑肌的电活动是由跨膜离子电流产生的, 其电活动形式主要为慢波电位和峰电位. 胃电图用于记录基本的电活性, 但是胃电活动可反映胃动力, 但是胃排空受诸多因素影响, 胃电图与胃排空能力没有直接相关性[31]. 重症患者记录胃电图操作性不强, 主要是因为检测时间过长.

4.2.1 氢呼气试验: 目前广泛用于测定小肠动力, 其原理是非吸收碳水化合物经过胃、小肠到达盲肠, 被结肠厌氧菌发酵产生H2, 由于氢分子量小, 可自由通过结肠黏膜扩散到血液中, 循环至肺, 从呼气中排出. 测定非吸收碳水化合物从摄入早呼出氢的时间代表食物从口腔至盲肠的运行时间. Ukleja[32]报道了ICU患者中小肠动力紊乱有较高的发生率, 31例ICU患者中有20例小肠转运的时间延长>6 h, 此外小肠压力测试也可用监测ICU患者的蠕动能力.

4.2.2 小肠X线检查: 使用造影剂硫酸钡、有机碘水造影剂等在X线透视下可对小肠的运动状况进行充分细致的观察, ICU重症患者经空肠管肠内营养时, 注入碘海醇造影剂, 可根据造影剂的下行速度对小肠的蠕动状况进行评估, 并判断空场营养时, 肠内营养液是否产生逆流到胃内. 因此, X线造影剂检测是评估小肠动力的一个非常重要而且直观的方法.

ICU重症患者肠动力紊乱以肠动力抑制为主要临床表现, 肠动力抑制的治疗目前循证的依据并不多[8]. 重症患者肠动力紊乱的影响因素也极其复杂, 除了竭力纠正原发病, 合适的液体管理, 纠正电解质紊乱, 改善肠道灌注, 合理镇痛镇静外, 还可考虑药物治疗[33].

尽管目前没有对ICU重症患者肠动力抑制患者使用肠动力药物治疗的时机的大样本研究, ICU重症患者在排除机械性肠梗阻、肠道灌注恢复、循环稳定后如仍存在肠动力抑制, 可考虑使用胃肠道动力药物. 目前, Herbert等[34]将ICU重症患者胃肠动力抑制的药物治疗分为: 早期支持治疗(early use of supportive therapeutic options)与目标靶向治疗(goal-directed specific therapies)两个方面. 早期支持治疗是指用一些刺激性泻剂(比沙可啶、匹可硫酸钠)、容积性泻药(镁盐)、聚乙二醇(Macrogol 3350)、阿片受体拮抗剂(纳洛酮)等药物来改善胃肠动力, 同时要注意减少抑制胃肠动力药物的使用, 如: 麻醉、镇静药物、阿片类、儿茶酚胺类药物等. 目标靶向治疗是指选择靶向性药物来改善胃动力或肠动力, 例如针对胃动力可选择红霉素、甲氧氯普胺(胃复安)、多潘立酮; 胃肠动力均抑制的患者可选择红霉素、甲氧氯普胺+新斯的明; 没有胃肌轻瘫而单纯以肠动力抑制为表现的可以选择蓝肽(又称黑蛙素, Ceruletide)、甲氧氯普胺+新斯的明.

甲氧氯普胺是一种多巴胺D2受体拮抗剂, 同时作为5-HT3受体拮抗剂和5-HT4受体激动剂, 具有中枢和外周作用. 甲氧氯普胺增加胃动力, 对小肠也具有温和的促动力作用[35]. 研究[36]表明其对危重病患者可能有效, 但对肠梗阻术后患者似乎无效. 对于肾功能衰竭的患者, 推荐的静脉剂量为10 mg, 3次/d, 必须逐渐减少; 血液透析患者的推荐剂量为10 mg/d[37].

西沙必利和替加色罗是5-HT4受体激动剂. 西沙必利增强食管蠕动, 增加食管下段和胃排空, 但其可引起Q-T间期延长和室性心律失常, 因此临床应用较少. 替加色罗加速胃排空, 缩短小肠和结肠转运时间[38]. 研究替加色罗对危重病患者胃肠运动紊乱效果的评价研究还很少, 目前只有一个报告[39]显示替加色罗对胃排空和呕吐具有积极影响.

大环内酯类红霉素通过作用于平滑肌细胞和肠神经元上的胃动素受体促进神经递质释放, 从而刺激胃肠运动[40]. 推荐剂量为250 mg口服2次/d或1-3 mg/公斤静脉注射, 每6 h一次[37]. 研究[41]表明每天给药两次, 药效持续时间可满足不能耐受肠内营养的危重症患者. 在推荐剂量的基础上, 一般用药时间不超过3-4 d.

蛙皮素, 可激活肠道神经元上的CCK受体, 释放兴奋性神经递质, 刺激小肠运动. 研究[42]证实临床使用[0.15-0.3 μg/(kg•d)]蛙皮素具有明显的促胃动力作用.

新斯的明, 乙酰胆碱酯酶抑制剂, 是一种间接的胆碱能兴奋剂, 被报道可以减少粪便和气体的通过时间. 有趣的是, 给药剂量越低(2-2.5 vs 9.6 mg/24 h), 气体和粪便通过的时间越短[43-45]. 这些研究结果表明新斯的明温和的促动力效应局限与一个较窄的浓度窗口, 高剂量则抑制小肠蠕动. 一些胃肠动力药物的作用靶点及效应(表2).

| 药物名称 | 胃 | 小肠 | 结肠 |

| 蛙皮素 | 0(-) | ++ | + |

| 西沙比利 | + | + | (+) |

| 多潘立酮 | + | + | 0 |

| 红霉素 | ++ | + | 0 |

| 甲氧氯普胺 | ++ | + | 0 |

| 新斯的明 | 0 | (+) | + |

| 奥曲肽 | (-) | + | 0 |

| 替加色罗 | + | (+) | (+) |

此外, 研究[46,47]表明饥饿素能加速动物模型的胃排空和小肠转运. 非多托嗪, κ-阿片受体激动剂, 动物研究[48]表明不仅具有良好的镇痛效应, 还提高肠功能. 爱维莫潘和受体拮抗剂均有益于患者胃肠功能恢复[49,50]. 认识胃肠动力紊乱类型和部位以及合理的治疗对改善肠道疾病和患者预后具有重要意义.

随着重症医学的发展, 越来越多的学者关注重症患者的胃肠道功能的保护, 胃肠道作为一个连续的消化系统管道, 不但具有受纳外来营养物质以消化吸收液体及营养, 同时可通过肠上皮屏障和肌层免疫系统防止肠道微生物入侵预防机体感染. 正常的胃肠道运动是自上而下推动摄入食物进行消化吸收, 重症患者胃肠道动力模式被破坏而紊乱, 因此充分认识维护重症患者正常的胃肠道动力, 对于改善患者预后、预防感染及早期成功实施肠内营养有重要意义.

胃肠功能紊乱经常发生于重症监护病房(intensive care unit, ICU)患者, 且容易被广大临床医师忽略, 影响患者预后. 但目前尚缺乏简便有效的临床监测方法, 因此了解目前的监测方法和治疗措施, 可帮助临床医师临床实践.

ICU患者胃肠功能紊乱和肠内营养问题一直是研究的热点, 也是临床医师关注的重点, 但目前亟待解决的问题是如何快速, 简便地监测患者胃肠功能? 新型的、简便的监测手段需要研发, 必将在临床广泛应用.

本文中从胃肠功能紊乱的病理生理, 临床特点, 监测手段和治疗方法, 系统地介绍了目前最新的观点和方法, 有助于临床医师的临床实践工作.

尽管临床有不少针对患者胃肠功能紊乱的药物, 但最为重要的是早期发现, 及时纠正, 个体化治疗方案. 本文介绍了目前临床可以利用的监测手段和治疗药物, 以及药物的使用方法和不良反应.

尽管先前的文献报道了很多监测胃肠功能的方法, 但目前仍缺少简便有效的实用方法, 尤其是目前的方法由于设备限制, 无法在临床推广. 因此, 研发新技术迫在眉睫.

胃排空: 食物由胃排入十二指肠的过程称为胃排空. 胃排空因其参与了许多疾病的病理生理过程, 并已成为干预药物代谢的目标之一而愈来愈受到人们的重视;

移行性复合运动(MMC): 在清醒空腹状态下胃肠出现的静息与收缩循环往复的周期性运动.

孔德润, 教授, 安徽医科大学第一附属医院消化科; 牛春燕, 教授, 主任医师, 西安医学院第一附属医院消化内科; 郑鹏远, 教授, 主任医师, 博士生导师, 郑州大学第五附属医院消化内科

本文介绍了ICU患者胃肠功能紊乱的病因、临床特点、临床监测和药物治疗, 可以使临床医师更好地认识胃肠功能紊乱的重要性.

手稿来源: 邀请约稿

学科分类: 胃肠病学和肝病学

手稿来源地: 贵州省

同行评议报告分类

A级 (优秀): 0

B级 (非常好): B

C级 (良好): 0

D级 (一般): D, D

E级 (差): 0

编辑: 闫晋利 电编:李瑞芳

| 1. | Sonne JU, Erckenbrecht JF. [Chronic motility disorders of the upper gastrointestinal tract in the elderly. Pharmaceutical, endoscopic and operative therapy]. Internist (Berl). 2014;55:852-858. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Luttikhold J, de Ruijter FM, van Norren K, Diamant M, Witkamp RF, van Leeuwen PA, Vermeulen MA. Review article: the role of gastrointestinal hormones in the treatment of delayed gastric emptying in critically ill patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:573-583. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Haag S, Senf W, Tagay S, Heuft G, Gerken G, Talley NJ, Holtmann G. Is there any association between disturbed gastrointestinal visceromotor and sensory function and impaired quality of life in functional dyspepsia? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:262-e79. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Takahashi A, Tomomasa T, Suzuki N, Kuroiwa M, Ikeda H, Morikawa A, Matsuyama S, Tsuchida Y. The relationship between disturbed transit and dilated bowel, and manometric findings of dilated bowel in patients with duodenal atresia and stenosis. J Pediatr Surg. 1997;32:1157-1160. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Madl C, Holzinger U. [Nutrition and gastrointestinal intolerance]. Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2013;108:396-400. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Reintam Blaser A, Jakob SM, Starkopf J. Gastrointestinal failure in the ICU. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2016;22:128-141. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Furness JB, Callaghan BP, Rivera LR, Cho HJ. The enteric nervous system and gastrointestinal innervation: integrated local and central control. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2014;817:39-71. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Fruhwald S, Holzer P, Metzler H. Intestinal motility disturbances in intensive care patients pathogenesis and clinical impact. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33:36-44. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Kusano M, Hosaka H, Kawada A, Kuribayashi S, Shimoyama Y, Zai H, Kawamura O, Yamada M. Gastrointestinal motility and functional gastrointestinal diseases. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20:2775-2782. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Müller-Lissner S, Bassotti G, Coffin B, Drewes AM, Breivik H, Eisenberg E, Emmanuel A, Laroche F, Meissner W, Morlion B. Opioid-Induced Constipation and Bowel Dysfunction: A Clinical Guideline. Pain Med. 2016; Dec 29. [Epub ahead of print]. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Lobo DN, Bostock KA, Neal KR, Perkins AC, Rowlands BJ, Allison SP. Effect of salt and water balance on recovery of gastrointestinal function after elective colonic resection: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1812-1818. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Nisanevich V, Felsenstein I, Almogy G, Weissman C, Einav S, Matot I. Effect of intraoperative fluid management on outcome after intraabdominal surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:25-32. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Farhadi A, Banan A, Fields J, Keshavarzian A. Intestinal barrier: an interface between health and disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18:479-497. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Floch MH. Intestinal microecology in health and wellness. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45 Suppl:S108-S110. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Martinez EE, Douglas K, Nurko S, Mehta NM. Gastric Dysmotility in Critically Ill Children: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2015;16:828-836. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Minami H, McCallum RW. The physiology and pathophysiology of gastric emptying in humans. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:1592-1610. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Miedema BW, Schillie S, Simmons JW, Burgess SV, Liem T, Silver D. Small bowel motility and transit after aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2002;36:19-24. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Mutlu GM, Mutlu EA, Factor P. Prevention and treatment of gastrointestinal complications in patients on mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Med. 2003;2:395-411. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Chapman MJ, Besanko LK, Burgstad CM, Fraser RJ, Bellon M, O'Connor S, Russo A, Jones KL, Lange K, Nguyen NQ. Gastric emptying of a liquid nutrient meal in the critically ill: relationship between scintigraphic and carbon breath test measurement. Gut. 2011;60:1336-1343. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Tomita T, Okugawa T, Yamasaki T, Kondo T, Toyoshima F, Sakurai J, Oshima T, Fukui H, Daimon T, Watari J. Use of scintigraphy to evaluate gastric accommodation and emptying: comparison with barostat. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:106-111. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Sanaka M, Nakada K. Paracetamol absorption test with Wagner-Nelson analysis for safe and accurate measurements of gastric emptying in women. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol. 2008;30:753-756. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Djerf P, Brundin M, Bajk M, Smedh U. Validation of the paracetamol absorption test for measuring gastric tube emptying in esophagectomized patients versus gold standard scintigraphy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:1339-1347. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Bruno G, Lopetuso LR, Ianiro G, Laterza L, Gerardi V, Petito V, Poscia A, Gasbarrini A, Ojetti V, Scaldaferri F. 13C-octanoic acid breath test to study gastric emptying time. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17 Suppl 2:59-64. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Creedon CT, Verhulst PJ, Choi KM, Mason JE, Linden DR, Szurszewski JH, Gibbons SJ, Farrugia G. Assessment of gastric emptying in non-obese diabetic mice using a [13C]-octanoic acid breath test. J Vis Exp. 2013;e50301. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Usai Satta P, Scarpa M, Oppia F, Loriga F. 13C-octanoic acid breath test in functional and organic disease: critical review of literature. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2005;9:9-13. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Manini ML, Burton DD, Meixner DD, Eckert DJ, Callstrom M, Schmit G, El-Youssef M, Camilleri M. Feasibility and application of 3-dimensional ultrasound for measurement of gastric volumes in healthy adults and adolescents. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;48:287-293. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Barreto EQ, Milani HJ, Araujo Júnior E, Haratz KK, Rolo LC, Nardozza LM, Moron AF. Reliability and validity of in vitro volume calculations by 3-dimensional ultrasonography using the multiplanar, virtual organ computer-aided analysis (VOCAL), and extended imaging VOCAL methods. J Ultrasound Med. 2010;29:767-774. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Kehl S, Becker L, Eckert S, Weiss C, Schaible T, Neff KW, Siemer J, Sütterlin M. Prediction of mortality and the need for neonatal extracorporeal membrane oxygenation therapy by 3-dimensional sonography and magnetic resonance imaging in fetuses with congenital diaphragmatic hernias. J Ultrasound Med. 2013;32:981-988. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Kar P, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Chapman MJ, Deane AM. Measurement of gastric emptying in the critically ill. Clin Nutr. 2015;34:557-564. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Carbone SF, Tanganelli I, Capodivento S, Ricci V, Volterrani L. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of the gastric emptying and antral motion: feasibility and reproducibility of a fast not invasive technique. Eur J Radiol. 2010;75:212-214. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Diamanti A, Bracci F, Gambarara M, Ciofetta GC, Sabbi T, Ponticelli A, Montecchi F, Marinucci S, Bianco G, Castro M. Gastric electric activity assessed by electrogastrography and gastric emptying scintigraphy in adolescents with eating disorders. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;37:35-41. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Ukleja A. Altered GI motility in critically Ill patients: current understanding of pathophysiology, clinical impact, and diagnostic approach. Nutr Clin Pract. 2010;25:16-25. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | von Arnim U. [Gastroparesis. Definition, diagnostics, and therapy]. Internist (Berl). 2015;56:625-630. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Herbert MK, Holzer P. Standardized concept for the treatment of gastrointestinal dysmotility in critically ill patients--current status and future options. Clin Nutr. 2008;27:25-41. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Booth CM, Heyland DK, Paterson WG. Gastrointestinal promotility drugs in the critical care setting: a systematic review of the evidence. Crit Care Med. 2002;30:1429-1435. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Delaney CP. Clinical perspective on postoperative ileus and the effect of opiates. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2004;16 Suppl 2:61-66. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Thompson JS, Quigley EM. Prokinetic agents in the surgical patient. Am J Surg. 1999;177:508-514. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Prather CM, Camilleri M, Zinsmeister AR, McKinzie S, Thomforde G. Tegaserod accelerates orocecal transit in patients with constipation-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:463-468. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Banh HL, MacLean C, Topp T, Hall R. The use of tegaserod in critically ill patients with impaired gastric motility. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2005;77:583-586. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Galligan JJ, Vanner S. Basic and clinical pharmacology of new motility promoting agents. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2005;17:643-653. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Chapman MJ, Fraser RJ, Kluger MT, Buist MD, De Nichilo DJ. Erythromycin improves gastric emptying in critically ill patients intolerant of nasogastric feeding. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:2334-2337. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Fruhwald S, Herk E, Hammer HF, Holzer P, Metzler H. Differential reversal of drug-induced small bowel paralysis by cerulein and neostigmine. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1414-1420. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | Paran H, Silverberg D, Mayo A, Shwartz I, Neufeld D, Freund U. Treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction with neostigmine. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:315-318. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | Abeyta BJ, Albrecht RM, Schermer CR. Retrospective study of neostigmine for the treatment of acute colonic pseudo-obstruction. Am Surg. 2001;67:265-268; discussion 268-269. [PubMed] |

| 45. | van der Spoel JI, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Stoutenbeek CP, Bosman RJ, Zandstra DF. Neostigmine resolves critical illness-related colonic ileus in intensive care patients with multiple organ failure--a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27:822-827. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Nematy M, O'Flynn JE, Wandrag L, Brynes AE, Brett SJ, Patterson M, Ghatei MA, Bloom SR, Frost GS. Changes in appetite related gut hormones in intensive care unit patients: a pilot cohort study. Crit Care. 2006;10:R10. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Trudel L, Tomasetto C, Rio MC, Bouin M, Plourde V, Eberling P, Poitras P. Ghrelin/motilin-related peptide is a potent prokinetic to reverse gastric postoperative ileus in rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G948-G952. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | De Winter BY, Boeckxstaens GE, De Man JG, Moreels TG, Herman AG, Pelckmans PA. Effects of mu- and kappa-opioid receptors on postoperative ileus in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;339:63-67. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Delaney CP, Weese JL, Hyman NH, Bauer J, Techner L, Gabriel K, Du W, Schmidt WK, Wallin BA; Alvimopan Postoperative Ileus Study Group. Phase III trial of alvimopan, a novel, peripherally acting, mu opioid antagonist, for postoperative ileus after major abdominal surgery. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:1114-1125; discussion 1125-1126; author reply 1127-1129. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Herbert PDMK, Holzer P, Roewer N. Problems of the Gastrointestinal Tract in Anesthesia, the Perioperative Period, and Intensive Care. Germany: Springer Berlin Heidelberg 1999; . |