修回日期: 2016-01-18

接受日期: 2016-01-23

在线出版日期: 2016-03-08

目的: 初步探讨人巨细胞病毒(human cytomegalovirus, HCMV)感染相关基因在大肠癌的表达及与大肠癌临床病理特征的关系.

方法: 巢式PCR方法检测60例大肠癌患者的肿瘤及癌旁正常肠黏膜组织HCMV UL135、UL136、US28及IE1基因; SDS-PAGE凝胶电泳分析结合基因测序方法验证巢式PCR结果的准确性, 用卡方检验或Fisher确切概率法比较两组间阳性率, Logistic回归分析HCMV感染与大肠癌患者临床病理特征的关系.

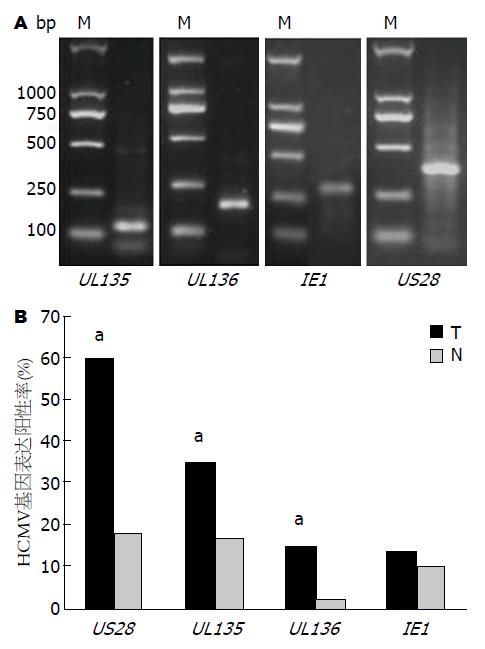

结果: SDS-PAGE凝胶电泳分析结合基因测序方法验证了巢式PCR结果的准确性. UL135、UL136及US28基因在大肠癌组织表达的阳性率分别为35.0%、15.0%及60.0%, 在癌旁正常肠组织的表达阳性率分别为16.7%、1.7%及18.3%, 两组具有显著性差异(均P<0.05); IE1在大肠癌组织表达的阳性率(13.3%)与癌旁组织表达阳性率(10%)差异无显著意义. Logistic回归分析HCMV基因与大肠癌患者临床病理特征的关系, 结果发现UL135、UL136及IE1基因表达与患者性别、年龄、肿瘤大小、病理分化程度、淋巴结转移及Dukes分期无关, 而US28基因表达与淋巴结转移及Dukes分期相关, 但和性别、年龄、肿块大小及病理分化程度无关.

结论: 大肠癌组织中UL135、UL136及US28基因表达较癌旁正常组织显著升高, 其中US28阳性表达与大肠癌淋巴结转移及Dukes分期相关, 提示HCMV某些基因表达可能参与大肠癌的发展.

核心提示: 多数研究表明人巨细胞病毒(human cytomegalovirus, HCMV)感染与大肠癌关系密切, 但HCMV感染后是否促进大肠癌的发展缺少临床证据, 本研究采用巢式PCR技术检测HCMV相关基因在肠癌中的表达及与临床病理特征的关系, 为HCMV在大肠癌发展中的作用提供临床证据.

引文著录: 何云, 叶梦思, 周羽翙, 林豪, 杨守醒, 薛战雄, 薛向阳, 蔡振寨. 人巨细胞病毒基因在大肠癌组织的表达及其临床意义. 世界华人消化杂志 2016; 24(7): 1024-1030

Revised: January 18, 2016

Accepted: January 23, 2016

Published online: March 8, 2016

AIM: To detect the expression of human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) infection related genes in colorectal cancer tissues and their relationship with clinicopathological features of colorectal cancer.

METHODS: HCMV UL135, UL136, US28 and IE1 gene expression in colorectal cancer tissues and corresponding adjacent normal samples was determined by nested PCR. The accuracy of nested PCR results was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and DNA sequencing analysis. The relationship between HCMV gene expression and clinicopathological features of patients with colorectal cancer was also analyzed. Statistical methods included Chi-square test or Fisher exact probability test and logistic regression model analysis.

RESULTS: The results of nested PCR were confirmed to be reliable. The positive expression rates of UL135, UL136 and US28 genes in the colorectal cancer tissues were 35.0%, 15.0% and 60.0%, respectively; and they were 16.7%, 1.7% and 18.3% in corresponding normal tissues. The positive expression rates of UL135, UL136 and US28 genes in the colorectal cancer tissues were significantly higher than those in corresponding normal tissues (P < 0.05 for all). There was no significant difference in the positive expression rate of IE1 between colorectal cancer tissues (13.3%) and corresponding normal tissues (10%). The expression of UL135, ULi136 and IE1 genes had no significant association with gender, age, tumor size, histological differentiation, metastasis or Dukes stage. The expression of US28 had a significant association with lymph node metastasis and Dukes stage, but not with age, gender, tumor size or histological differentiation.

CONCLUSION: UL135, UL136 and US28 gene expression is more often found in colorectal cancer tissues than in corresponding normal tissues, among which US28 has a significant association with lymph node metastasis and Dukes stage of colorectal cancer. Our findings suggest that some HCMV genes may play a role in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer.

- Citation: He Y, Ye MS, Zhou YH, Lin H, Yang SX, Xue ZX, Xue XY, Cai ZZ. Clinical significance of expression of human cytomegalovirus genes in colorectal cancer. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2016; 24(7): 1024-1030

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v24/i7/1024.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v24.i7.1024

人巨细胞病毒(human cytomegalovirus, HCMV)是人群普遍感染的一种疱疹病毒[1], 且多以潜伏感染使人群长期携带病毒. 已有研究报道HCMV感染与大肠癌密切相关[2-4], HCMV基因组约含200个开放阅读框(open reading frame, ORF)[5,6], 编码至少22条microRNA[7-10]及一些长链非编码RNA(long non-coding RNAs, lncRNA)[11], 这些基因在大肠癌组织及癌旁正常组织表达是否有差异及是否与大肠癌的发生发展相关? 目前研究较少. 本研究使用巢式聚合酶链反应(nested polymerase chain reaction, PCR)研究病毒潜伏相关基因UL135、UL136、US28及病毒复制相关基因IE1在大肠癌的表达及其与临床病理特征的关系. 为深入研究HCMV相关基因功能提供临床依据.

60例大肠癌标本来自于2013-12/2015-05经内镜活检提示肠癌并在温州医科大学附属第二医院行手术切除者, 60例配对标本取自癌旁正常肠黏膜组织(距肿瘤组织5 cm以上), 所有患者手术前均未行化疗或放射性治疗. 其中男32例, 女28例, 年龄34-84岁, 平均61.1岁±11.5岁. 标本于离体后30 min内保存在液氮中备用, 所有肿瘤病理分化程度判定由两位高年资病理科医师确定, 患者均签署知情同意书, 本课题由温州医科大学附属第二医院伦理委员会通过. 组织基因组DNA提取试剂盒、琼脂糖凝胶DNA回收试剂盒购自天根生化科技有限公司; KOD-plus试剂盒购自日本Toyobo公司, pMD19-T连接试剂盒购自TaKaRa公司; E. coli DH 5α菌株由本实验室保存; PCR引物由本实验室设计并委托上海生工生物工程有限公司合成.

1.2.1 大肠癌组织DNA提取: 标本DNA提取步骤参照组织基因组DNA提取试剂盒说明书. 所有提取的组织DNA经分光光度计测浓度后保存于-20 ℃备用.

1.2.2 巢式PCR检测大肠癌组织及癌旁正常肠组织HCMV基因表达: 根据我们实验室前期的研究, 选取UL135、UL136、US28及IE1基因作为检测的靶基因, 将提取的组织DNA进行巢式PCR鉴定. 第一轮PCR反应体系为: DNA模板1.0 μL, Kod-plus酶0.5 μL, 10×buffer 2.5 μL, 2.5 mmol/L dNTPs 2.5 μL, 25 mmol/L MgSO4 1.0 μL, 20 μmol/L外引物各1.0 μL, ddH2O 15.5 μL, 引物系列及反应条件如表1. 第二轮PCR反应体系为: 第一轮PCR产物1.0 μL, Kod-plus 0.5 μL, 10×buffer 2.5 μL, 2.5 mmol/L dNTP 2.5 μL, 25 mmol/L MgSO4 1.0 μL, 20 μmol/L内引物各1.0 μL, ddH2O 15.5 μL, 反应条件同第一轮PCR, 反应结束后0.1 mg/mL EB染色, 260 nm紫外成像. 并将扩增目的片段进行琼脂糖凝胶DNA回收, 步骤参照试剂盒说明书. 回收后连于pMD19-T载体, 并转化至E. coli DH 5α感受态细胞内, 挑取阳性单克隆并用M13通用引物鉴定后, 送上海生工生物工程有限公司测序鉴定.

| 基因 | 引物(5'-3') | PCR条件 | ||||

| 正向 | 反向 | 退火温度(℃) | 退火时间(s) | 循环 | 目标片段大小(bp) | |

| UL135 | ATGGTGTGGCTGTGGCTCGGCGTCGGGCTCCTCG1 | TCAGGTCATCTGCATTGACTCGGCGTCCTTCATG1 | 65 | 30 | 35 | 927 |

| UL136 | GGATGGTCTGCCGATAGATAAACCCG2 | CGCTGGCCGAGGACGACAAAGA2 | 57 | 30 | 35 | 143 |

| ATGTCAGTCAAGGGCGTGGAGATGC1 | TTACGTAGCGGGAGATACGGCGTTC1 | 60 | 30 | 35 | 723 | |

| GCGGTGTTTCACGTTATCTGTGC2 | ATGGCTCGCCGTCTGCTTCT2 | 65 | 30 | 35 | 191 | |

| US28 | TCGCGCCACAAAGGTCGCAT | GACGCGACACACCTCGTCGG | 60 | 30 | 33 | 390 |

| IE1 | AGCCTTCCCTAAGACCACCAAT | CATAGCAGCACAGC ACCCGACA | 60 | 30 | 32 | 290 |

统计学处理 采用SPSS22.0统计学软件进行统计学处理. 2组之间阳性率比较采用卡方检验或者Fisher确切概率法, 基因表达与临床病理学特征的关系用Logistic回归分析. P<0.05为差异有统计学意义.

本实验通过巢式PCR对大肠癌及其癌旁正常组织中的HCMVUL135、UL136、IE1及US28进行扩增, 可见部分组织DNA经两轮PCR后在2%琼脂糖凝胶中可出现特异性条带(图1A), 结果显示得到目的条带, 送上海生工生物工程有限公司的测序结果亦证实基因产物的准确性.

巢式PCR法检测4个HCMV基因在大肠癌及癌旁正常肠组织表达的阳性率结果显示US28在大肠癌组织中的表达阳性率(36/60, 60.0%)最高, 而IE1在大肠癌组织表达的阳性率(8/60, 13.3%)最低. 而在癌旁正常肠组织中US28表达阳性率(11/60, 18.3%)也是最高, 而UL136在癌旁正常肠组织中几乎不表达, 仅1.7%. UL135、UL136及US28在癌组织的检出率均明显高于在癌旁正常组织的检出率(P<0.05). 而IE1在癌组织及癌旁正常组织的检出率无明显差别(图1B).

进一步分析HCMV基因表达与患者临床病理资料发现, UL135、UL136及IE1基因表达与性别、年龄、肿瘤大小、病理分化程度、淋巴转移及Dukes分期无关, 而US28表达则与肿瘤淋巴转移及Dukes分期相关, 而与性别、年龄、肿瘤大小及肿瘤分化程度无关(表2).

| 临床参数 | US28 | UL135 | UL136 | IE1 | ||||||||

| 阳性 | 阴性 | P值 | 阳性 | 阴性 | P值 | 阳性 | 阴性 | P值 | 阳性 | 阴性 | P值 | |

| 性别 | 0.92 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 0.86 | ||||||||

| 男 | 19 | 13 | 11 | 21 | 5 | 27 | 5 | 27 | ||||

| 女 | 17 | 11 | 10 | 18 | 4 | 24 | 3 | 25 | ||||

| 年龄(岁) | 0.75 | 0.55 | 0.77 | 0.98 | ||||||||

| <60 | 15 | 11 | 8 | 18 | 3 | 23 | 4 | 22 | ||||

| ≥60 | 21 | 13 | 13 | 21 | 6 | 28 | 4 | 30 | ||||

| 肿瘤大小(cm) | 0.29 | 0.42 | 0.15 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| <5 | 16 | 14 | 12 | 18 | 2 | 28 | 4 | 26 | ||||

| ≥5 | 20 | 10 | 9 | 21 | 7 | 23 | 4 | 26 | ||||

| 分化程度 | 0.29 | 0.34 | 0.85 | 0.59 | ||||||||

| 高中分化 | 19 | 16 | 14 | 21 | 6 | 29 | 6 | 29 | ||||

| 低分化 | 17 | 8 | 7 | 18 | 3 | 22 | 2 | 23 | ||||

| 淋巴转移 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.94 | ||||||||

| 有 | 24 | 9 | 13 | 20 | 5 | 28 | 5 | 28 | ||||

| 无 | 12 | 15 | 8 | 19 | 4 | 23 | 3 | 24 | ||||

| Dukes分期 | 0.03 | 0.43 | 0.74 | 0.94 | ||||||||

| A-B | 12 | 15 | 8 | 19 | 4 | 23 | 3 | 24 | ||||

| C-D | 24 | 9 | 13 | 20 | 5 | 28 | 5 | 28 | ||||

肿瘤的发生是一个多因素参与的复杂过程, 是环境因素和遗传因素共同作用的结果, 环境因素或生活方式决定了绝大多数肿瘤的发病, 已经得到公认[12]. 随着人乳头瘤病毒疫苗预防宫颈癌的成功, 感染作为肿瘤的诱因引起了研究者的极大关注, 并成为目前肿瘤病因和发生机制研究的热点. 据统计, 2008年全球约有16.1%的肿瘤归因于感染因素, 而发展中国家则约22.9%的肿瘤与感染有关[13]. 越来越多研究表明[14-17], HCMV感染与某些恶性肿瘤有关, 如脑肿瘤, 乳腺癌, 前列腺癌,横纹肌肉瘤. 多个文献报道[2-4,18], 结肠癌组织HCMV DNA阳性率明显高于癌旁正常组织, HCMV感染与结肠癌密切相关, HCMV可能作为一种促癌因素存在. 本研究检测4个HCMV基因发现HCMV潜伏感染相关基因UL135、UL136及US28在大肠癌组织表达阳性率明显高于癌旁正常肠黏膜组织, 进一步验证了HCMV感染与大肠癌相关.

在HCMV潜伏感染期间, 病毒基因组在宿主体内持续存在, 缺乏病毒显性感染的表现, 仅有少部分基因组表达[19,20]. 目前关于HCMV感染状态与肿瘤组织关系的研究少有报道. Jin等[21]报道胃癌肿瘤上皮组织和正常上皮组织中表达IE1基因和UL133-UL138基因, 其中UL133、UL135、UL136在肿瘤组织和正常组织中表达有显著性差异, 但IE1基因表达无显著性差异. IE1基因在HCMV病毒DNA复制、病毒再激活及单核巨噬细胞分化中起重要作用[22,23]. 本研究结果表明潜伏感染相关基因UL135、UL136及US28在大肠癌组织和癌旁正常组织中表达存在显著差异, 而代表显性感染的IE1基因在大肠癌及癌旁正常组织表达无差异, 说明HCMV潜伏感染表达的基因与大肠癌的发生、发展关系密切, 未来可更加侧重研究HCMV潜伏感染相关基因在大肠癌发生、发展中的作用.

目前尚无正常组织感染HCMV病毒后直接发生癌变的现象, 因此目前无关键证据证明病毒感染与肿瘤发生直接相关[24,25], 但越来越多证据均显示, HCMV感染可作为一种促癌因素参与肿瘤的发生、发展. HCMV感染后可能通过以下途径促进肿瘤的发展: (1)诱导染色体断裂: HCMV感染时, 在细胞的DNA合成期(S期)会出现特殊的1号染色体断裂[26], 这种染色体不完整性联合其他细胞毒性因子会明显弱化宿主基因组稳定性, 阻断DNA修复途径, 被认为是主要的促癌条件[27,28]; (2)激活癌基因: HCMV编码的病毒调控蛋白和病毒非编码RNA可直接激活癌基因、下调抑癌基因的表达, 影响细胞增殖、凋亡、分化、迁移等功能, 促使正常受感染细胞向恶性表型的转变和多种肿瘤的进展[29-31]; (3)激活磷脂酰肌醇-3-激酶(phosphatidyl inositol 3-kinase, PI3K)/Akt等信号通路: 在神经胶质瘤中, Cobbs等[32]发现HCMV的IE1基因和IE2基因可引诱激活PI3K/Akt致癌信号通路, 利用氧化磷酸化抑制Rb蛋白功能, 降低p53蛋白家族的表达; 病毒的糖蛋白B能够结合多种细胞表面的血小板衍生生长因子(platelet-derived growth factor, PDGF)受体由PI3K通路激活AKT来影响核因子-κB(nuclear factor-κB, NF-κB)信号, 也可通过Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(mitogen-activated protein kinase, MAPK)通路改变凋亡反应和肿瘤细胞的性能[24]. HCMV编码的US28蛋白可促进肿瘤表型细胞的复制周期和周期素D1的表达[25]; (4)抑制肿瘤细胞凋亡: HCMV可通过PI3K/AKT和Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK/MAPK信号通路抑制肿瘤细胞凋亡, 而病毒的立早基因可通过肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor α, TNF-α)、p53依赖或非p53依赖的机制也能发挥其抗肿瘤凋亡作用[33]; (5)改变肿瘤微环境: HCMV基因本身不但编码人白介素-10(interleukin-10, IL-10)的同源物(LAvIL-10)抑制宿主免疫[34-36], 而且HCMV感染的细胞可分泌多种细胞因子[如IL-10及转化生长因子-β(transforming growth factor beta, TGF-β)]、细胞外基质蛋白及血管生成因子改变肿瘤微环境[37-42]. 本研究进一步分析HCMV基因表达与临床病理特征发现, UL135、UL136及IE1基因表达与临床病理特征无显著相关, 而US28与大肠癌转移及Dukes分期显著相关, 有趣的是, Soroceanu等[24,30]亦报道US28基因在脑胶质瘤的表达可以促进转移及血管生成作用, 以上结果表明US28可能具有促进大肠癌发展的作用.

总之, 本研究结果提示HCMV潜伏感染相关基因UL135、UL136及US28在大肠癌及癌旁正常组织表达存在显著差异, 说明HCMV潜伏感染与大肠癌密切相关. 进一步分析HCMV基因与大肠癌临床病理特征结果显示US28与大肠癌淋巴转移及Dukes分期显著相关, 说明US28可能在大肠癌的发展中具有促进作用, 其机制值得深入研究.

人巨细胞病毒(human cytomegalovirus, HCMV)是人群普遍感染的一种疱疹病毒, 且以潜伏感染为主而长期携带病毒. 研究表明, HCMV感染与某些恶性肿瘤有关, 如脑肿瘤、乳腺癌、结肠癌、前列腺癌及横纹肌肉瘤等. HCMV与结肠癌的关系研究目前大多局限于结肠癌组织HCMV的检出率, 缺乏HCMV感染后不同基因表达与临床病理特征关系的比较研究.

白雪, 副主任医师, 中国人民解放军北京军区总医院普通外科; 许洪卫, 主任医师, 大连大学附属新华医院胃肠微创外科中心, 大连大学消化病研究所

HCMV感染后相关基因在大肠癌组织及癌旁正常组织表达是否有差异及是否与大肠癌的发生发展相关? 目前研究较少. 本研究使用巢式PCR研究病毒潜伏相关基因UL135、UL136、US28及病毒复制相关基因IE1在大肠癌的表达及其与临床病理特征的关系, 为深入研究HCMV相关基因功能提供临床依据.

以HCMV潜伏感染相关基因UL135、UL136、US28及病毒复制相关基因IE1为靶基因检测其在大肠癌组织及癌旁正常肠组织的表达差异并结合临床病理特征分析, 有助进一步明确HCMV感染在大肠癌发生、发展中的作用, 相关报道较少.

研究HCMV感染后哪些基因在大肠癌组织表达及其与临床病理特征的关系, 有助于进一步明确HCMV在大肠癌发生、发展中的作用, 也为大肠癌的防治提供理论依据.

巢式PCR: 是一种变异的聚合酶链反应(PCR), 使用两对PCR引物扩增完整的片段. 巢式PCR的好处在于, 如果第一次扩增产生了错误片段, 则第二次能在错误片段上进行引物配对并扩增的概率极低. 因此, 巢式PCR的扩增非常特异、有效.

本文涉及的研究国内相关报道较少, 创新性强, 书写流畅, 具有一定的临床意义.

编辑: 郭鹏 电编: 都珍珍

| 1. | Staras SA, Dollard SC, Radford KW, Flanders WD, Pass RF, Cannon MJ. Seroprevalence of cytomegalovirus infection in the United States, 1988-1994. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:1143-1151. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Harkins L, Volk AL, Samanta M, Mikolaenko I, Britt WJ, Bland KI, Cobbs CS. Specific localisation of human cytomegalovirus nucleic acids and proteins in human colorectal cancer. Lancet. 2002;360:1557-1563. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Dimberg J, Hong TT, Skarstedt M, Löfgren S, Zar N, Matussek A. Detection of cytomegalovirus DNA in colorectal tissue from Swedish and Vietnamese patients with colorectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2013;33:4947-4950. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Tafvizi F, Fard ZT. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in patients with colorectal cancer by nested-PCR. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:1453-1457. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Davison AJ, Dolan A, Akter P, Addison C, Dargan DJ, Alcendor DJ, McGeoch DJ, Hayward GS. The human cytomegalovirus genome revisited: comparison with the chimpanzee cytomegalovirus genome. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:17-28. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Murphy E, Rigoutsos I, Shibuya T, Shenk TE. Reevaluation of human cytomegalovirus coding potential. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13585-13590. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Fannin Rider PJ, Dunn W, Yang E, Liu F. Human cytomegalovirus microRNAs. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:21-39. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Dunn W, Trang P, Zhong Q, Yang E, van Belle C, Liu F. Human cytomegalovirus expresses novel microRNAs during productive viral infection. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1684-1695. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Pfeffer S, Sewer A, Lagos-Quintana M, Sheridan R, Sander C, Grässer FA, van Dyk LF, Ho CK, Shuman S, Chien M. Identification of microRNAs of the herpesvirus family. Nat Methods. 2005;2:269-276. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Stark TJ, Arnold JD, Spector DH, Yeo GW. High-resolution profiling and analysis of viral and host small RNAs during human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 2012;86:226-235. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Gatherer D, Seirafian S, Cunningham C, Holton M, Dargan DJ, Baluchova K, Hector RD, Galbraith J, Herzyk P, Wilkinson GW. High-resolution human cytomegalovirus transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:19755-19760. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Peto J. Cancer epidemiology in the last century and the next decade. Nature. 2001;411:390-395. [PubMed] |

| 13. | de Martel C, Ferlay J, Franceschi S, Vignat J, Bray F, Forman D, Plummer M. Global burden of cancers attributable to infections in 2008: a review and synthetic analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:607-615. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Samanta M, Harkins L, Klemm K, Britt WJ, Cobbs CS. High prevalence of human cytomegalovirus in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia and prostatic carcinoma. J Urol. 2003;170:998-1002. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Lau SK, Chen YY, Chen WG, Diamond DJ, Mamelak AN, Zaia JA, Weiss LM. Lack of association of cytomegalovirus with human brain tumors. Mod Pathol. 2005;18:838-843. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Harkins LE, Matlaf LA, Soroceanu L, Klemm K, Britt WJ, Wang W, Bland KI, Cobbs CS. Detection of human cytomegalovirus in normal and neoplastic breast epithelium. Herpesviridae. 2010;1:8. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Cinatl J, Cinatl J, Radsak K, Rabenau H, Weber B, Novak M, Benda R, Kornhuber B, Doerr HW. Replication of human cytomegalovirus in a rhabdomyosarcoma cell line depends on the state of differentiation of the cells. Arch Virol. 1994;138:391-401. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | 侯 治富, 杨 绍娟, 王 维忠, 张 文岚, 吴 晓冬. 人巨细胞病毒与大肠癌相关关系的研究. 中华实验和临床病毒学杂志. 2004;14:299. |

| 19. | Nachmani D, Stern-Ginossar N, Sarid R, Mandelboim O. Diverse herpesvirus microRNAs target the stress-induced immune ligand MICB to escape recognition by natural killer cells. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:376-385. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Bego MG, St Jeor S. Human cytomegalovirus infection of cells of hematopoietic origin: HCMV-induced immunosuppression, immune evasion, and latency. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:555-570. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Jin J, Hu C, Wang P, Chen J, Wu T, Chen W, Ye L, Zhu G, Zhang L, Xue X. Latent infection of human cytomegalovirus is associated with the development of gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2014;8:898-904. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Taylor-Wiedeman J, Sissons P, Sinclair J. Induction of endogenous human cytomegalovirus gene expression after differentiation of monocytes from healthy carriers. J Virol. 1994;68:1597-1604. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Reeves MB, MacAry PA, Lehner PJ, Sissons JG, Sinclair JH. Latency, chromatin remodeling, and reactivation of human cytomegalovirus in the dendritic cells of healthy carriers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4140-4145. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Soroceanu L, Akhavan A, Cobbs CS. Platelet-derived growth factor-alpha receptor activation is required for human cytomegalovirus infection. Nature. 2008;455:391-395. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Maussang D, Verzijl D, van Walsum M, Leurs R, Holl J, Pleskoff O, Michel D, van Dongen GA, Smit MJ. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded chemokine receptor US28 promotes tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:13068-13073. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Fortunato EA, Spector DH. Viral induction of site-specific chromosome damage. Rev Med Virol. 2006;13:21-37. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Albrecht T, Deng CZ, Abdel-Rahman SZ, Fons M, Cinciripini P, El-Zein RA. Differential mutagen sensitivity of peripheral blood lymphocytes from smokers and nonsmokers: effect of human cytomegalovirus infection. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2004;43:169-178. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Luo MH, Rosenke K, Czornak K, Fortunato EA. Human cytomegalovirus disrupts both ataxia telangiectasia mutated protein (ATM)- and ATM-Rad3-related kinase-mediated DNA damage responses during lytic infection. J Virol. 2007;81:1934-1950. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Michaelis M, Doerr HW, Cinatl J. The story of human cytomegalovirus and cancer: increasing evidence and open questions. Neoplasia. 2009;11:1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Cinatl J, Vogel JU, Kotchetkov R, Wilhelm Doerr H. Oncomodulatory signals by regulatory proteins encoded by human cytomegalovirus: a novel role for viral infection in tumor progression. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2004;28:59-77. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Cobbs CS, Soroceanu L, Denham S, Zhang W, Kraus MH. Modulation of oncogenic phenotype in human glioma cells by cytomegalovirus IE1-mediated mitogenicity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:724-730. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Zhu H, Shen Y, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins block apoptosis. J Virol. 1995;69:7960-7970. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Kotenko SV, Saccani S, Izotova LS, Mirochnitchenko OV, Pestka S. Human cytomegalovirus harbors its own unique IL-10 homolog (cmvIL-10). Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1695-1700. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Slobedman B, Barry PA, Spencer JV, Avdic S, Abendroth A. Virus-encoded homologs of cellular interleukin-10 and their control of host immune function. J Virol. 2009;83:9618-9629. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Spencer JV, Lockridge KM, Barry PA, Lin G, Tsang M, Penfold ME, Schall TJ. Potent immunosuppressive activities of cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10. J Virol. 2002;76:1285-1292. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Botto S, Streblow DN, DeFilippis V, White L, Kreklywich CN, Smith PP, Caposio P. IL-6 in human cytomegalovirus secretome promotes angiogenesis and survival of endothelial cells through the stimulation of survivin. Blood. 2011;117:352-361. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Dumortier J, Streblow DN, Moses AV, Jacobs JM, Kreklywich CN, Camp D, Smith RD, Orloff SL, Nelson JA. Human cytomegalovirus secretome contains factors that induce angiogenesis and wound healing. J Virol. 2008;82:6524-6535. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Fiorentini S, Luganini A, Dell'Oste V, Lorusso B, Cervi E, Caccuri F, Bonardelli S, Landolfo S, Caruso A, Gribaudo G. Human cytomegalovirus productively infects lymphatic endothelial cells and induces a secretome that promotes angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis through interleukin-6 and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Gen Virol. 2011;92:650-660. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Streblow DN, Dumortier J, Moses AV, Orloff SL, Nelson JA. Mechanisms of cytomegalovirus-accelerated vascular disease: induction of paracrine factors that promote angiogenesis and wound healing. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:397-415. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Chang WL, Baumgarth N, Yu D, Barry PA. Human cytomegalovirus-encoded interleukin-10 homolog inhibits maturation of dendritic cells and alters their functionality. J Virol. 2004;78:8720-8731. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Mason GM, Jackson S, Okecha G, Poole E, Sissons JG, Sinclair J, Wills MR. Human cytomegalovirus latency-associated proteins elicit immune-suppressive IL-10 producing CD4⁺ T cells. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003635. [PubMed] [DOI] |