修回日期: 2015-04-28

接受日期: 2015-05-07

在线出版日期: 2015-06-18

目的: 探讨了糖基化终末产物(advanced glycation end products, AGE)及其受体(receptor for advanced glycation end products, RAGE)在糖尿病大鼠胃组织中的分布.

方法: 糖尿病模型组与正常组大鼠饲养8 wk, 测量空腹血糖、糖化血清蛋白、胃壁组织学, 免疫组织化学检测AGE与RAGE在胃壁组织的表达.

结果: 模型组大鼠胃黏膜层(781.47 μm±137.82 μm vs 709.85 μm±169.41 μm)和黏膜下层(233.39 μm±134.05 μm vs 109.32 μm±44.43 μm)的厚度较正常组显著增加(P<0.05); AGE与RAGE在模型组大鼠胃组织的黏膜层(5.66±1.90 vs 2.25±0.52, 2.79±0.54 vs 1.70±0.30)和肌层(37.37±7.38 vs 24.32±4.02, 4.26±0.80 vs 3.59±0.37)的分布较正常组显著增加(P<0.05).

结论: AGE与RAGE在糖尿病大鼠的胃组织中表达上调, 该异常分布可能与糖尿病胃肠功能障碍有关.

核心提示: 利用链脲佐菌素(streptozotocin)腹腔注射大鼠糖尿病模型, 观察到糖基化终末产物(advanced glycation end products)及其受体(receptor for advanced glycation end products)在糖尿病大鼠胃组织中表达上调, 该异常分布可能在糖尿病并发胃肠功能障碍中发挥作用.

引文著录: 田佳星, 赵静波, 李敏, 李君玲, 曹洋, HansGregersen, 仝小林. 糖基化终末产物及其受体在糖尿病大鼠胃组织中的分布. 世界华人消化杂志 2015; 23(17): 2714-2721

Revised: April 28, 2015

Accepted: May 7, 2015

Published online: June 18, 2015

AIM: To observe the distribution of advanced glycation end products (AGEs) and their receptor (RAGE) in the stomach of diabetic rats.

METHODS: Diabetes mellitus (DM) and control (CON) rats were reared for eight weeks. Fasting plasma glucose (FPG), glycated serum protein (GSP) and gastric layer thickness were measured. The expression of AGEs and RAGE was detected by immunohistochemical staining.

RESULTS: The thickness of the mucosa (781.47 μm ± 137.82 μm vs 709.85 μm ± 169.41 μm) and submucosa (233.39 μm ± 134.05 μm vs 109.32 μm ± 44.43 μm) increased significantly in the DM group compared with the CON group (P < 0.05). The expression of AGEs and RAGE in the mucosa (5.66 ± 1.90 vs 2.25 ± 0.52, 2.79 ± 0.54 vs 1.70 ± 0.30) and muscle (37.37 ± 7.38 vs 24.32 ± 4.02, 4.26 ± 0.80 vs 3.59 ± 0.37) layers of the stomach was significantly higher in the DM group than in the CON group (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The expression of AGEs and RAGE is up-regulated in the stomach of diabetic rats. The increased levels of AGE and RAGE in gastric tissue may contribute to diabetic gastrointestinal dysfunction.

- Citation: Tian JX, Zhao JB, Li M, Li JL, Cao Y, Gregersen H, Tong XL. Distribution of advanced glycation end products and their receptor in the stomach of diabetic rats. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2015; 23(17): 2714-2721

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v23/i17/2714.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v23.i17.2714

糖尿病胃轻瘫是胃机械性排泄梗阻导致胃排空延迟的综合征, 主要临床表现以上消化道症状为主, 包括恶心、呕吐、早饱、餐后饱胀、腹胀腹痛等[1-4]. 胃排空为胃底张力和胃窦收缩结合胃幽门部抑制及十二指肠收缩的复杂运动, 需要平滑肌、肠道自主神经和起搏细胞Cajal间质细胞(interstitial cells of cajal, ICC)的共同作用[5-7]. 糖尿病状态下多种异常因素可致胃肠运动功能障碍, 包括自主神经病变、ICC功能异常、空腹及餐后血糖的急速波动及心理因素[8,9]. 近年研究[10-13]表明糖尿病状态下胃的组织形态学及生物力学特性发生重构, 其与糖尿病胃肠功能障碍密切相关, 但是其作用机制尚未明确阐释.

糖基化终末产物(advanced glycation end-products, AGE)为糖的醛基或羰基与蛋白质的氨基基团发生无酶反应形成糖-蛋白质产物, 经过一系列脱氢和碳骨架裂解反应后转化成稳定的共价化学物质[14]. 糖基化终末产物受体(receptor for advanced glycation end-products, RAGE)是一种多配体膜受体, AGE与配体结合后可启动多条信号通路, 导致细胞功能紊乱, 在糖尿病并发症发生和发展中起重要作用[15-17]. Tanji等[18]研究发现, 在糖尿病患者的体内组织中, AGE及其受体表达增加. Ling等[19]研究发现AGE在正常和糖尿病大鼠胃及小肠的上皮细胞有表达. 但目前尚未有详细的AGE及其受体在胃组织分布的研究报道. 本研究探讨AGE及其受体在正常和糖尿病大鼠胃组织的分布, 从而为探讨AGE及其受体在糖尿病胃肠道合并症中的作用奠定基础.

选取SPF级♂Wistar大鼠(北京华阜康生物科技股份有限公司, 质量合格证编号: SCXK京2009-007), 体质量180-220 g. 抗AGE抗体(ab23722)为兔多克隆抗体抗RAGE抗体(ab3611)为兔多克隆抗体, 其均购自美国abcam生物有限公司; 第二抗体为北京中杉金桥生物技术有限公司的PV-6000. 链脲佐菌素(streptozotocin, STZ)(美国Sigama公司产品); 水合三氯乙醛(国药集团化学试剂有限公司); 强生血糖仪、稳豪血糖试纸(强生医疗器材有限公司); 大鼠糖化血清蛋白(glycated serum protein, GSP)果糖胺法试剂盒(南京建成公司).

1.2.1 实验动物模型建立及分组: 造模前12 h大鼠禁食不禁水. STZ溶于0.l mmol/L的柠檬酸钠缓冲液(pH 4.5)中, 配置成浓度为1%的溶液. 按65 mg/kg的剂量腹腔一次性注射[9], 72 h后用快速葡萄糖分析仪测定空腹血糖值,≥16.9 mmol/L者为模型组(DM)造模成功. 6只正常大鼠为空白对照组(CON); 6只STZ造模大鼠为DM.

1.2.2 糖代谢指标检测: 空腹血糖(fasting plasma glucose, FPG): 给药后第4周和8周末尾静脉采血测定; GSP: 末次给药后, 腹主动脉取血, 果糖胺法检测.

1.2.3 免疫组织化学染色检测AGE及RAGE的表达: 大鼠在水合三氯乙醛麻醉状态下取全胃, 组织经40 g/L甲醛固定24 h以上. 乙醇逐级脱水、透明、浸蜡, 石蜡包埋, 切片. 组织切片用免疫组织化学染色和HE染色. 采用双盲法评价肠壁各层的厚度. AGE免疫组织化学染色: 3%双氧水-甲醇溶液抑制内源性过氧化物酶. 滴加第一抗体(稀释度为1:300), 在4 ℃冰箱内孵育过夜. 用PBS(0.01 mol/L)充分洗涤3次, 3 min/次, 滴加第二抗体, 37 ℃ 15 min. 经PBS充分洗涤3次, 3 min/次, 滴加新鲜配置的DAB, 室温下显色2 min. RAGE免疫组织化学染色: 抗RAGE抗体为兔源性多克隆抗体, 其合成肽序列对应的大鼠RAGE的氨基酸第362-380位. 3%双氧水-甲醇溶液抑制内源性过氧化物酶. 第一抗体稀释度为1:200. 其余步骤与AGE免疫组织化学染色相同. AGE及RAGE染色阳性区域均为棕黄色. 而在阴性对照中并未出现, 说明染色为特异性染色. 详细染色方法如参考文献[9]. AGE及RAGE染色阳性区域均为棕黄色, 根据棕黄色在组织中的分布, 在相同条件下对染色切片进行图像采集, 每张切片分别在100倍和200倍视野下分别于黏膜、黏膜下层及肌层随机选取视野, 拍摄出来的图片利用NIS-Element软件进行分析, 描述其分布状态, 并确定AGE及RAGE染色部分所占该层组织的染色阳性面积比例.

统计学处理 采用SPSS16.0软件作统计分析, 实验数据计量资料以mean±SD表示, 服从正态分布的两组间均数比较用t检验进行统计. P<0.05为差异具有统计学意义.

如表1所示, 与正常组相比, 模型组FPG及GSP均显著升高, 差异有统计学意义(P<0.01).

如表2所示, 与正常组比较, 模型组大鼠胃组织黏膜层、黏膜下层厚度以及总壁厚均显著增加, 差异有统计学意义(P<0.01, P<0.05).

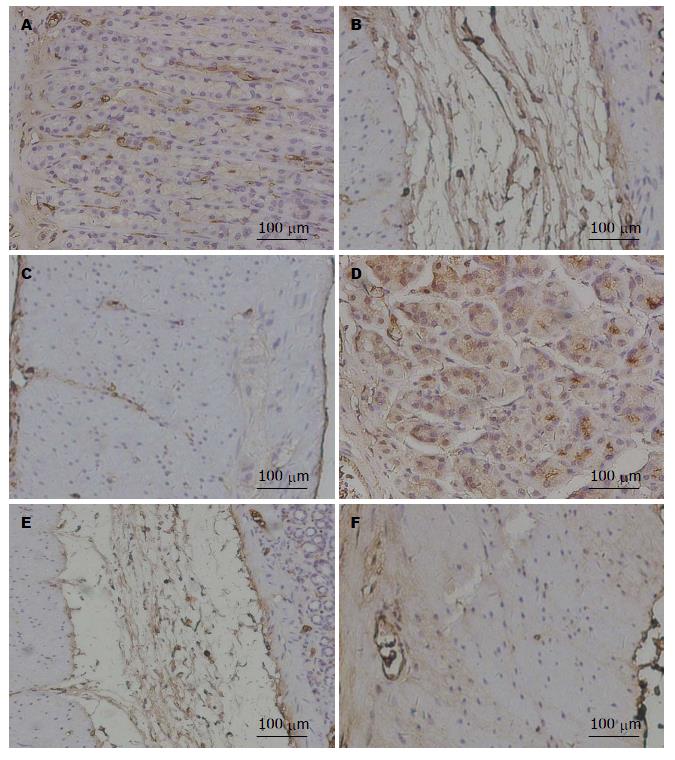

如图1所示, AGE主要分布在黏膜下层、胃上皮单层柱状上皮细胞及胃底腺主细胞, 肌层染色较弱, 胃黏膜层基底部分比表面部分表达加强. 正常组与模型组均为黏膜下层染色最强. 与正常组相比, 模型组各层染色均明显增强, 其中模型组黏膜层、肌层染色显著加强, 差异有统计学意义(P<0.01, P<0.05)(表3).

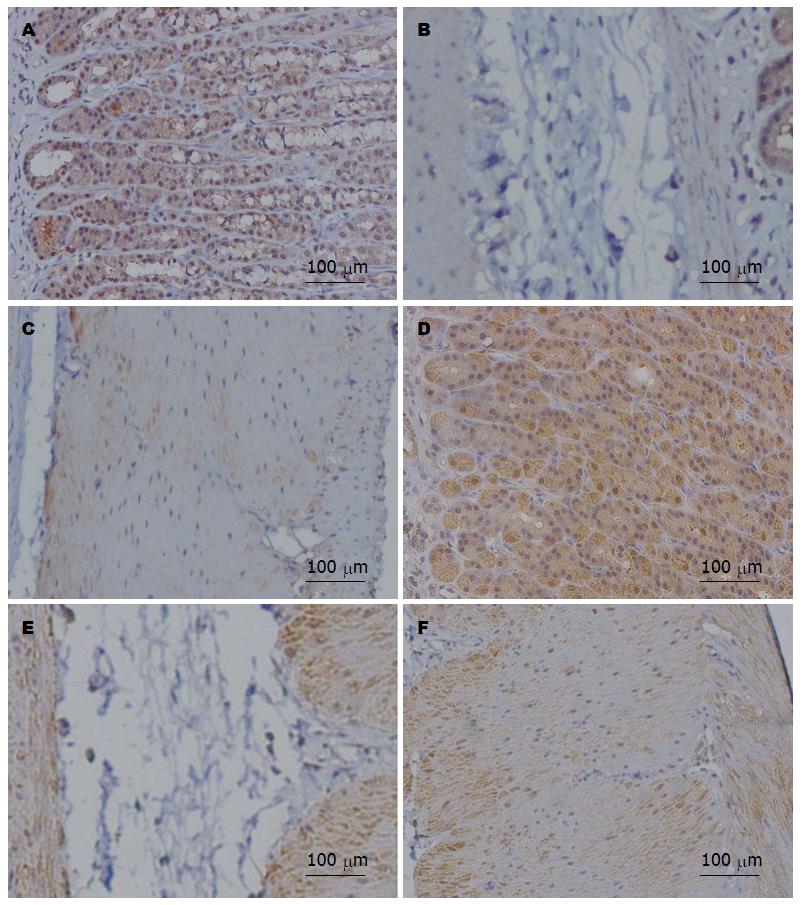

如图2所示, 主要分布在黏膜层、胃底腺壁细胞和主细胞、肌层及神经节内的神经细胞. 黏膜下层染色极为微弱. 其在细胞内为均匀性分布, 但不同部位染色强度有所差异, 胃黏膜层基底部分比表面部分表达加强. 正常组与模型组均为黏膜层染色最强. 与正常组相比, 黏膜层和肌层的染色显著加强, 差异有统计学意义(P<0.01, P<0.05)(表4).

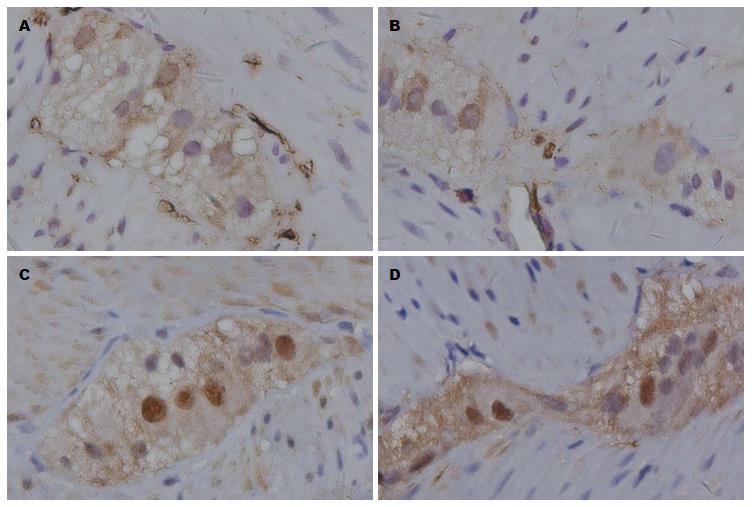

如图3所示, AGE在胃壁神经节内表达不如RAGE明显. 与正常组相比, 模型组大鼠AGE和RAGE在胃壁神经节内表达无明显改变.

正常生理情况既有AGE的形成, 人体老化和糖尿病状态下AGE的形成和沉积加速[20-24]. 我们前期研究证明STZ所致DM大鼠小肠和结肠的AGE和RAGE表达增加[25]. 但对AGE及其受体在胃组织中表达尚乏详细研究报道. 本研究发现AGE主要分布在胃的黏膜下层、胃黏膜上皮细胞及胃底腺主细胞. 而RAGE主要分布在胃的黏膜层、胃底腺壁细胞和主细胞、肌层及神经节内的神经细胞. 糖尿病状态下, AGE和RAGE在黏膜和肌层的表达上调. 未来的研究中我们将采用双染同时在胃组织中定位AGE及其受体, 以进一步明确两者之间的表达关系.

AGE及其受体在胃肠道组织呈过度表达, 可能与糖尿病胃肠病变包括糖尿病性胃轻瘫相关[26]. 胃具有分泌胃酸和蛋白酶的功能, AGE和RAGE在主细胞和壁细胞的过度表达, 可能影响胃蛋白酶的结构及功能, 破坏理化特性及功能, 影响胃酸的正常分泌. AGE和RAGE在胃壁平滑肌的过度表达, 可能会影响平滑肌的收缩和调节功能. AGE和RAGE在胃肠道组织中的过度表达, 可能会导致胃壁组织形态学和生物力学特性的重构, 且与AGE和RAGE的过度表达相关[27]. 另外, 糖尿病胃肠病变与自主神经病变密切相关, 因此AGE及其受体的过度表达可能在糖尿病胃肠神经病变的发生发展过程中发挥重要作用. 因此, 糖尿病状态下胃壁组织AGE和RAGE表达的改变可能是胃肠动力功能紊乱的机制之一.

沉积的AGE可直接或通过受体途径影响和促进糖尿病胃肠病变的发生和发展. AGE能够影响基质间、细胞间及细胞-基质间的作用, 病理状态下过度的交联导致基质硬化[28],

胞外基质蛋白的改变可能导致胞内AGE重新修饰, 从而改变生理蛋白的作用[29], 进一步影响细胞的分泌及复制; AGE还能够通过直接改变胞内蛋白的转运影响蛋白功能. 此外, AGE与RAGE结合可影响依赖ROS的NAD(P)H酶和线粒体的生成[30], AGE还可以通过RAGE激活由于胞外基质蛋白过度沉积而致纤维化的下游通路, 并诱导产生各种趋化因子[31]. 但是有关AGE和RAGE如何影响胃壁的各种细胞的结构和功能以及其具体作用途径需要进行进一步的深入研究. 总之, 本研究详细观察了AGE及受体在胃壁组合中的表达, 为进一步探究糖尿病胃肠病变的发病机制奠定了基础.

糖尿病状态下胃的组织形态学及生物力学特性发生重构, 与糖尿病胃肠功能障碍密切相关, 但是其作用机制尚未被明确阐释.

宁钧宇, 副研究员, 北京市疾病预防控制中心卫生毒理所

糖基化终末产物(advanced glycation end-products, AGE)及糖基化终末产物受体(receptor for advanced glycation end-products, RAGE)在糖尿病并发症发生和发展中起重要作用, 本研究发现, 在糖尿病患者的体内组织中, AGE及其受体表达增加, 为糖尿病的研究提供新的线索.

相关的研究证明, 链脲佐菌素(streptozotocin, STZ)所致DM大鼠小肠和结肠的AGE和RAGE表达增加, 但对AGE及其受体在胃组织中表达尚乏详细研究报道.

本研究探讨AGE及其受体在正常和糖尿病大鼠胃组织的分布, 从而为糖尿病胃肠道合并症的研究开创新的途径.

本研究详细观察了AGE及受体在胃壁组合中的表达, 为进一步探究糖尿病胃肠病变的发病机制奠定了基础.

本研究观察AGE及RAGE在糖尿病大鼠胃壁各层组织中的分布, 显示AGEs及RAGE均明显增加, 可能在糖尿病并发胃肠功能障碍中发挥作用, 具有一定的理论及应用意义.

编辑: 郭鹏 电编:都珍珍

| 1. | Camilleri M, Bharucha AE, Farrugia G. Epidemiology, mechanisms, and management of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:5-12; quiz e7. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Thazhath SS, Jones KL, Horowitz M, Rayner CK. Diabetic gastroparesis: recent insights into pathophysiology and implications for management. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;7:127-139. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Bytzer P, Talley NJ, Leemon M, Young LJ, Jones MP, Horowitz M. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms associated with diabetes mellitus: a population-based survey of 15,000 adults. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:1989-1996. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Khoo J, Rayner CK, Jones KL, Horowitz M. Pathophysiology and management of gastroparesis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:167-181. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | He CL, Soffer EE, Ferris CD, Walsh RM, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Loss of interstitial cells of cajal and inhibitory innervation in insulin-dependent diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:427-434. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Kashyap P, Farrugia G. Diabetic gastroparesis: what we have learned and had to unlearn in the past 5 years. Gut. 2010;59:1716-1726. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Hasler WL. Gastroparesis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;8:438-453. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Horowitz M, Samsom M. Gastrointestinal function in diabetes mellitus. First edition. UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd 2004; 1-339. |

| 9. | Aljarallah BM. Management of diabetic gastroparesis. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:97-104. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Zhao J, Frøkjaer JB, Drewes AM, Ejskjaer N. Upper gastrointestinal sensory-motor dysfunction in diabetes mellitus. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:2846-2857. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Zeng YJ, Yang J, Zhao JB, Liao DH, Zhang EP, Gregersen H, Xu XH, Xu H, Xu CQ. Morphologic and biomechanical changes of rat oesophagus in experimental diabetes. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2519-2523. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Zhao J, Liao D, Gregersen H. Biomechanical and histomorphometric esophageal remodeling in type 2 diabetic GK rats. J Diabetes Complications. 2007;21:34-40. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Zhao J, Nakaguchi T, Gregersen H. Biomechanical and histomorphometric colon remodelling in STZ-induced diabetic rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1636-1642. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Bierhaus A, Hofmann MA, Ziegler R, Nawroth PP. AGEs and their interaction with AGE-receptors in vascular disease and diabetes mellitus. I. The AGE concept. Cardiovasc Res. 1998;37:586-600. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Singh VP, Bali A, Singh N, Jaggi AS. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic complications. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2014;18:1-14. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Chen M, Curtis TM, Stitt AW. Advanced glycation end products and diabetic retinopathy. Curr Med Chem. 2013;20:3234-3240. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Vlassara H, Uribarri J. Advanced glycation end products (AGE) and diabetes: cause, effect, or both? Curr Diab Rep. 2014;14:453. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Tanji N, Markowitz GS, Fu C, Kislinger T, Taguchi A, Pischetsrieder M, Stern D, Schmidt AM, D'Agati VD. Expression of advanced glycation end products and their cellular receptor RAGE in diabetic nephropathy and nondiabetic renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2000;11:1656-1666. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ling X, Nagai R, Sakashita N, Takeya M, Horiuchi S, Takahashi K. Immunohistochemical distribution and quantitative biochemical detection of advanced glycation end products in fetal to adult rats and in rats with streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Lab Invest. 2001;81:845-861. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Méndez JD, Xie J, Aguilar-Hernández M, Méndez-Valenzuela V. Trends in advanced glycation end products research in diabetes mellitus and its complications. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;341:33-41. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Wautier MP, Tessier FJ, Wautier JL. [Advanced glycation end products: A risk factor for human health]. Ann Pharm Fr. 2014;72:400-408. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Prasad C, Imrhan V, Marotta F, Juma S, Vijayagopal P. Lifestyle and Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs) Burden: Its Relevance to Healthy Aging. Aging Dis. 2014;5:212-217. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Neves D. Advanced glycation end-products: a common pathway in diabetes and age-related erectile dysfunction. Free Radic Res. 2013;47 Suppl 1:49-69. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Nedić O, Rattan SI, Grune T, Trougakos IP. Molecular effects of advanced glycation end products on cell signalling pathways, ageing and pathophysiology. Free Radic Res. 2013;47 Suppl 1:28-38. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Chen P, Zhao J, Gregersen H. Up-regulated expression of advanced glycation end-products and their receptor in the small intestine and colon of diabetic rats. Dig Dis Sci. 2012;57:48-57. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Zhao J, Chen P, Gregersen H. Morpho-mechanical intestinal remodeling in type 2 diabetic GK rats--is it related to advanced glycation end product formation? J Biomech. 2013;46:1128-1134. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Chang KC, Liang JT, Tsai PS, Wu MS, Hsu KL. Prevention of arterial stiffening by pyridoxamine in diabetes is associated with inhibition of the pathogenic glycation on aortic collagen. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;157:1419-1426. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Mott JD, Khalifah RG, Nagase H, Shield CF, Hudson JK, Hudson BG. Nonenzymatic glycation of type IV collagen and matrix metalloproteinase susceptibility. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1302-1312. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Coughlan MT, Thorburn DR, Penfold SA, Laskowski A, Harcourt BE, Sourris KC, Tan AL, Fukami K, Thallas-Bonke V, Nawroth PP. RAGE-induced cytosolic ROS promote mitochondrial superoxide generation in diabetes. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;20:742-752. [PubMed] [DOI] |