修回日期: 2013-09-15

接受日期: 2013-09-17

在线出版日期: 2013-11-28

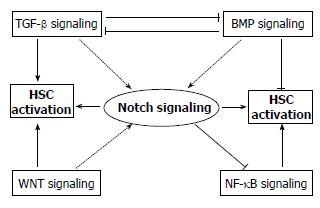

肝纤维化的发生与多种信号通路密切相关, 有研究证实Notch信号通路在肝星状细胞(hepatic stellate cell, HSC)活化过程起重要作用. Notch通路主要通过直接及间接与转化生长因子β(transforming growth factor β, TGF-β)/BMP、核因子-κB(nuclear factor-kappa B, NF-κB)、WNT等信号通路的协同作用参与HSC的活化. 本文主要就Notch信号通路与HSC活化的关系, 该信号通路在HSC的活化过程中与TGF-β/BMP、NF-κB、WNT等信号通路的协同作用作一评述.

核心提示: 本文不仅较全面的阐述了Notch与肝星状细胞(hepatic stellate cell, HSC)活化的关系及研究现状, 也进一步讨论了Notch与转化生长因子β(transforming growth factor β)/BMP、核因子-κB(nuclear factor-kappa B)、WNT等信号通路在HSC活化过程中的协调作用, 为寻找调节HSC活化的关键分子提供了一些新思路.

引文著录: 张凯, 艾文兵, 柳长柏, 吴江锋. Notch信号通路与HSC活化关系的研究进展. 世界华人消化杂志 2013; 21(33): 3611-3616

Revised: September 15, 2013

Accepted: September 17, 2013

Published online: November 28, 2013

Multiple signaling pathways are involved in the pathogenesis of hepatic fibrosis, and the Notch signaling pathway plays an important role in promoting the activation of hepatic stellate cells (HSCs). This pathway participates in the activation of HSCs mainly by cooperating with transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)/BMP, nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and Wnt signaling pathways directly or indirectly. This review aims to explore the relationship between the Notch signaling pathway and the activation of HSCs as well as the cooperative actions between TGF-β/BMP, NF-κB, and Wnt and the Notch signaling pathway in the process of the activation of HSCs.

- Citation: Zhang K, Ai WB, Liu CB, Wu JF. Progress in understanding the relationship between Notch signaling pathway and hepatic stellate cell activation. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2013; 21(33): 3611-3616

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v21/i33/3611.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v21.i33.3611

肝损伤-炎症-修复导致肝星状细胞(hepatic stellate cell, HSC)活化, 分泌大量的胶原蛋白, 引起细胞外基质(extracellular matrix, ECM)的合成与降解失调, 是肝纤维化(hepatic fibrosis, HF)形成的关键[1,2]. 静止的HSC位于Dessel间隙, 他富含维生素A(vitamin A, VA)和甘油三酯等成份形成的脂滴[3-5]. 静止期的HSC经活化、转分化为肌成纤维细胞(myofibroblast, MF)后, 发生了多种变化, 主要包括致纤维化基因的表达、具有收缩性和趋化作用、细胞增殖、脂滴丢失、白细胞因子的释放等[6]. 以上变化与HSC的多个信号通路有关,研究证实Notch通路的失活可抑制HSC的活化[7-9], 但具体机制并不清楚. 因此, 通过对Notch通路的深入研究, 可能寻找到与HSC活化的关键分子, 并以此作为治疗靶点, 阻止甚至逆转HSC活化[10]. 本文就Notch信号通路在HSC中的研究现状及潜在的治疗意义作一综述.

Notch信号通路由Notch受体、Notch配体(DSL蛋白)、CSL(CBF-1, Suppressor of hairless, Lag的合称)DNA结合蛋白、其他的效应物和Notch的调节分子等组成. 哺乳动物细胞中有4种Notch受体(Notch1-4)和5种Notch配体(Delta-like 1, 3, 4, Jagged1和Jagged2). Notch受体为Ⅰ型跨膜蛋白, 当他与相邻细胞膜上的Notch配体结合后, 激活Notch信号通路, 招募2种蛋白水解酶. 一种为金属解素酶(a disintegrin and metalloprotease, ADAM), 另一种是衰老素(presenillin)介导的γ型分泌酶(γ-secretase). ADAM作用于Notch受体的跨膜外区域, γ型分泌酶作用于胞内区域, 两者共同将Notch受体水解为胞外区、跨膜区及胞内结构域NICD(Notch intracellular domain)[11,12].

NICD是Notch受体的主要功能结构区, 由2个核定位序列(nuclear localization sequence, NLS)、1个RAM区(主要与CSL蛋白结合)、6个ANK(ankyrin, 主要负责与核内相关蛋白结合形成转录复合物)重复序列及维持蛋白稳定的PEST(proline-glutamate-serine-threonine-rich domain)序列组成[13,14]. NICD可向细胞核内聚集并与核内的RBP-Jκ[binding protein-Jkappa, 也被称作CSL或CBF1/Su(H)/Lag-1]核蛋白家族及p300、Maml等蛋白形成转录复合物. 当RBP-Jκ与NICD结合后, RBP-Jκ由转录抑制因子变为转录激活因子(transcriptional activator), 从而使Notch信号通路的直接靶基因Hes(hairy-enhancer of split)与Hey(hairy/enhancer of split-related with YRPW motif-like)及间接靶基因cmyc、jag1、CD25等表达[15].

Notch作为一个进化高度保守的信号通路, 广泛存在于各种哺乳动物细胞中并精密的调节着细胞、组织、器官的分化和发育. 尤其是在血液与免疫系统的进化和发育方面起着至关重要的作用, 如Notch在胚胎形成时期能促进造血干细胞的形成,并维系造血干细胞在骨髓中的微环境[16]; 同样, Notch对维持T细胞的分化与成熟至关重要, 骨髓来源的前体T细胞需要高水平的Notch信号诱导其定植于胸腺并分化成熟[17]. 因此, Notch信号通路长期被用于免疫及血液系统疾病的研究. 随着分子生物学的发展, Notch通路越来越多地被用于其他疾病的研究. 如在人的肺、肾、肝脏、隔膜等纤维化疾病的研究中, 发现Notch能与生长转化因子β(transforming growth factor β, TGF-β)作用促进或降解EMC, 选择性的介导纤维化发生[18,19].

慢性肝损伤分泌的大量炎症因子所导致的HSC活化是肝纤维化形成的关键. 在原代细胞水平, 通过对正常大鼠肝脏中刚分离出的HSC与培养不同天数并高度活化的HSC进行对比, 发现Notch受体和配体的表达存在显著差异[20]. 在静止期HSC中并没有Notch配体Jag1的表达, 但在肝实质细胞、枯否细胞及高度活化的HSC中Jag1有表达. 表明静止期的HSC需要肝脏的其他细胞提供Notch配体, 拟维持Notch信号的活化. 对于HSC中Notch受体及其下游靶基因的分布情况, 研究发现在静止期HSC中, Notch受体Notch1、Notch2、Notch4及其靶基因Hes1、Hey1都有大量的表达[21,22], 但伴随着HSC的活化, 以上基因的表达都有逐渐降低的趋势, 其中, Notch1的变化最明显, 在HSC的活化过程中, 干细胞标记分子CD133、OCT4的表达也逐渐下降[20,22], 以上Notch相关分子与干细胞标记分子之间有何关联, 值得进一步探讨. 随着HSC的活化, Notch3的表达量却显著增高. 目前已证实, Notch3与HSC的活化有一定关联[23,24]. 当Notch3的胞内功能结构域(NICD3)在HSC-T6细胞系中高表达时, 该细胞的纤维化标志分子α平滑肌肌动蛋白(α-smooth muscle actin, α-SMA)、Ⅰ型胶原蛋白(collagenⅠ)等都显著增加; 但是, 当Notch3被小干扰RNA(siRNA)沉默后, 这两种蛋白的表达并无显著增高. 同时, 动物实验证实, 肝纤维化组织中Notch3、hes1、jagged1、α-SMA 、CollagenⅠ的表达显著增高[9].

虽然已有实验证实, 抑制Notch3的表达能有效抑制HSC的活化. 但Notch3作为Notch通路中的上游分子, 其下游的靶点过多, 干预Notch3的表达后, 会表现为多效性的特点, 因此, 单独依靠抑制Notch3的表达来抑制HSC活化, 并用于临床肝纤维化治疗并不现实. 若进一步弄清Notch3与HSC活化之间的具体分子机制, 找到Notch3下游与HSC活化更密切、更特异性的分子, 可以为肝纤维化的治疗开辟新途径. 而对于Notch信号通路的另外3种受体Notch1、Notch2、Notch4与HSC的活化关系并没有相关文献报道, 对肝纤维化治疗感兴趣的国内外学者仍值得继续探究.

Notch与TGF-β信号通路具有协同作用. 研究表明, TGF-β的下游分子Smad3既可结合该信号通路的靶基因启动子上的Smad结合元件(Smad binding elements, SBEs), 又可结合Notch信号通路的下游分子CSL. 一方面, TGF-β具有促进Notch信号的作用: TGF-β通过活化Smad2/3蛋白, 使其与Notch信号的下游分子NICD直接作用, 并结合到Hes1基因的启动子上, 上调Hes1基因的表达[19,25,26]; 另一方面, Notch信号通路也可强化TGF-β的作用: Notch信号通路可以提高Smad2/3的磷酸化水平[27], 增加Smad3蛋白的表达量, 延长Smad3蛋白的半衰期, 上调TGF-β/Smad3靶基因的表达. 此外, 这两条信号通路通过协同作用, 可以上调α-SMA的表达, 深入研究发现, Notch1/CSL可以直接活化α-SMA的启动子[28], 当阻断Notch信号通路时, TGF-β所诱导的α-SMA的表达上调受到抑制[29].

同时, Notch与BMP信号通路也有协同作用. 当BMP信号通路活化后, Notch信号通路靶基因Hes的表达显著增高[30]. 进一步研究Notch与BMP之间的内在关系发现, 在小鼠的神经上皮细胞中, BMP2激活的Smad1可与NICD结合形成复合体, 并在p300分子的协助下结合到Hes基因的启动子上, 进而上调Hes5、Herp1基因的表达[31]. 在内皮细胞中也发现, BMP可调节Notch信号通路的另一靶基因Herp2[32].

在HSC中, TGF-β与BMP的功能不同, TGF-β促进HSC活化, 而BMP抑制了该过程. 由上可知, Notch与TGF-β及BMP信号通路之间均通过"串话"起到协调效应. 那么, 在HSC的活化过程中, 是以Notch与TGF-β信号通路的协调作用为主, 还是以Notch与BMP信号通路的协调作用为主, 或者Notch信号通路能否有效地协调这两种相互拮抗的信号通路, 值得进一步探讨.

NF-κB信号通路与许多病理过程有关联, 如慢性炎症、持续感染、癌症等[33,34]. 同样, NF-κB所介导的炎症介质释放也是导致HSC活化的关键. 在活化的HSC中, 许多致炎症因子及致纤维化因子如肿瘤坏死因子α、白介素-6(interleukin-6, IL-6)、IL-8、单核细胞趋化蛋白1(monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, MCP-1)及ICAM1都受细胞内NF-κB基础水平的调控[35,36]. 同时, NF-κB也保护性的调节细胞存活并抵抗细胞因子诱导的HSC凋亡[37,38]. 因此, 调节HSC中NF-κB的基础水平可调控HSC的活化.

在正常细胞中, 构成型NF-κB蛋白表达恒定, 在胞质内, 大部分NF-κB前体分子会与NF-κB抑制蛋白IκB(NF-κB-inhibitory protein)形成复合物, 遏制NF-κB蛋白进入细胞核发挥转录因子的作用; 当细胞受到各种炎症因子刺激后, 产生IκB激酶(IκB kinase, IKK), 该激酶使IκB的稳定性降低, 进而降解IκB, 活化NF-κB信号通路[39,40]. 由此可见, 增加胞质内IκB蛋白的表达是遏制NF-κB通路活化的有效手段.

在HSC中, Notch1的活化能增加胞质内IκB蛋白的基础表达, 抑制NF-κB通路活化[41]. 细胞内IκB蛋白的表达是受核内多种转录复合物调控的, 其中转录抑制因子(C-promoter binding protein-1, CBF1)是IκB基因表达的关键调节因子. 当CBF1与SMRT-NcoR-HDAC1或CIR-HDAC2-SAP30等结合后会形成转录抑制复合体, 与IκB基因启动子结合后抑制IκB基因的表达, 活化NF-κB通路[42]. 而当细胞内高表达Notch1后, 大量的Notch1胞内结构域NICD入核, 招募CBP/P300等蛋白并与转录抑制复合体竞争性结合CBF1, 使转录抑制复合物变为转录激活子从而活化IκB基因的表达[43,44]. 可见, 在HSC中高表达的Notch1能增加胞质内IκB蛋白的表达, 抑制NF-κB通路的活化.

研究证实WNT信号通路促进HSC活化. 通过对比WNT受配体及其下游的分子在静止期和活化期原代HSC中的表达, 发现WNT信号在活化的HSC中显著增强[45,46]. 在HSC-T6细胞系中进一步证实, 当WNT信号通路活化后, 细胞表达ECM的水平显著增加; 当用内源性阻断剂DDK1阻断WNT信号通路后, ECM的表达无变化, 该结果表明, 增强的WNT信号确能促进HSC活化[47,48]. 在经典的WNT信号通路中, WNT通路的上游信号分子Necdin与Wnt10b的启动子结合, 激活Wnt信号通路, 通过抑制过氧化物酶增殖物激活受体γ(peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ, PPARγ), 进而影响VA的代谢, 促进HSC活化, 这可能是WNT信号通路促进HSC活化的一种机制[49-51].

研究发现, 当HSC中的WNT信号增强时, Notch1的表达会显著增加; 而当WNT信号被阻断时, Notch1的表达显著降低[7]. 表明WNT信号在HSC中有调节Notch1表达的功能. 在结肠癌(HCT116)细胞系中发现, 经典的WNT信号活化后, 下游的β-catenin蛋白表达增高, 该蛋白能与Notch2、Notch3、Notch4启动子上的LEF-1/TCF位点结合, 进而使他们的表达增高, 其中Notch2有显著增高趋势[52-54]. 因此, 在HSC中可能存在WNT调节Notch相关受体表达的机制, 但要阐明此种机制需进一步研究(图1).

Notch信号可与多种信号通路协同调节HSC的活化, 但是, 由于Notch信号通路具有多效性, 继续寻找与HSC活化更密切、更特异性的分子, 并以此为靶点进行干预性靶向治疗, 可能成为逆转HSC活化的有效手段之一. 就研究现状而言, 只是初步发现Notch信号通路可与多种信号通路共同调节HSC的活化, 具体是哪些分子在HSC的活化中起关键性作用并不明确. 因此, 要想进一步明确Notch信号通路中各个分子在HSC活化中的作用, 还需国内外学者共同努力, 本文主要阐述了Notch信号通路在HSC活化过程中的研究现状及其与TGF-β/BMP、NF-κB、WNT等信号通路在HSC活化过程中的可能的内在联系, 期望为肝纤维化的研究提供一些思路及为临床治疗肝纤维化提供一条新途径.

本文简要阐述了Notch与肝星状细胞(hepatic stellate cell, HSC)活化的关系及研究现状, 意在让读者对Notch与HSC活化的关系有更全面的了解, 为肝纤维化的分子靶向治疗提供可能方向.

吴俊华, 副教授, 南京大学医学院; 刘绍能, 主任医师, 中国中医科学院广安门医院消化科

由于Notch通路在血液及免疫系统发育过程中的重要性, 过去人们更多关注其对血液及免疫系统疾病的治疗. 目前, Notch在治疗纤维化疾病方面的研究也已取得重大进展, 进一步研究可能为纤维化疾病的治疗找到新的突破口.

Notch能调节HSC的活化虽已有相关文献报道, 特别是Notch3的失活能抑制HSC活化有望用于治疗肝纤维化. 但调节HSC活化的关键分子并不清楚, 有待国内外学者进一步探究.

目前人们更多的关注于TGF-β信号在HSC活化中的作用, 而本文全面总结了Notch信号与HSC活化的关系及研究现状, 为肝纤维化的研究提供了一些新思路.

由于HSC的活化是受多因素共同调节的, 本文较全面的阐述了Notch与HSC活化的关系, 有助于肝纤维化研究者更好的分析实验数据、解释实验现象及把握实验方向.

本文呈现的内容以及作者的某些观点对于相关领域的研究者具有一定指导意义.

编辑: 田滢 电编:鲁亚静

| 1. | Frantz C, Stewart KM, Weaver VM. The extracellular matrix at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:4195-4200. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Yu J, Zhang S, Chu ES, Go MY, Lau RH, Zhao J, Wu CW, Tong L, Zhao J, Poon TC. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors gamma reverses hepatic nutritional fibrosis in mice and suppresses activation of hepatic stellate cells in vitro. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:948-957. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Ramani K, Tomasi ML. Transcriptional regulation of methionine adenosyltransferase 2A by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in rat hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2012;55:1942-1953. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | D'Ambrosio DN, Walewski JL, Clugston RD, Berk PD, Rippe RA, Blaner WS. Distinct populations of hepatic stellate cells in the mouse liver have different capacities for retinoid and lipid storage. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24993. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, Yee H, Zender L, Lowe SW. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657-667. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Chen YX, Weng ZH, Zhang SL. Notch3 regulates the activation of hepatic stellate cells. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:1397-1403. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Chen YX, Weng ZH, Qi D, Zhang SL. [Effect of Notch signaling on the activation of hepatic stellate cells]. Zhonghua Ganzangbing Zazhi. 2012;20:677-682. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Chen Y, Zheng S, Qi D, Zheng S, Guo J, Zhang S, Weng Z. Inhibition of Notch signaling by a γ-secretase inhibitor attenuates hepatic fibrosis in rats. PLoS One. 2012;7:e46512. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Friedman SL. Liver fibrosis -- from bench to bedside. J Hepatol. 2003;38 Suppl 1:S38-S53. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Erler F. [Osteosyntheses in forearm fractures (1972)]. Beitr Orthop Traumatol. 1976;23:132-134. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Nemir M, Pedrazzini T. Functional role of Notch signaling in the developing and postnatal heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:495-504. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Ohtani T, Pear WS. Notch regulation of early thymocyte development. Semin Immunol. 2010;22:261-269. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Artavanis-Tsakonas S, Rand MD, Lake RJ. Notch signaling: cell fate control and signal integration in development. Science. 1999;284:770-776. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Iso T, Kedes L, Hamamori Y. HES and HERP families: multiple effectors of the Notch signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2003;194:237-255. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Dzierzak E, Speck NA. Of lineage and legacy: the development of mammalian hematopoietic stem cells. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:129-136. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Tanigaki K, Han H, Yamamoto N, Tashiro K, Ikegawa M, Kuroda K, Suzuki A, Nakano T, Honjo T. Notch-RBP-J signaling is involved in cell fate determination of marginal zone B cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:443-450. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Bielesz B, Sirin Y, Si H, Niranjan T, Gruenwald A, Ahn S, Kato H, Pullman J, Gessler M, Haase VH. Epithelial Notch signaling regulates interstitial fibrosis development in the kidneys of mice and humans. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4040-4054. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Nyhan KC, Faherty N, Murray G, Cooey LB, Godson C, Crean JK, Brazil DP. Jagged/Notch signalling is required for a subset of TGFβ1 responses in human kidney epithelial cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:1386-1395. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Sawitza I, Kordes C, Reister S, Häussinger D. The niche of stellate cells within rat liver. Hepatology. 2009;50:1617-1624. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Ono Y, Sensui H, Okutsu S, Nagatomi R. Notch2 negatively regulates myofibroblastic differentiation of myoblasts. J Cell Physiol. 2007;210:358-369. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Reister S, Kordes C, Sawitza I, Häussinger D. The epigenetic regulation of stem cell factors in hepatic stellate cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:1687-1699. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Guo LY, Li YM, Qiao L, Liu T, Du YY, Zhang JQ, He WT, Zhao YX, He DQ. Notch2 regulates matrix metallopeptidase 9 via PI3K/AKT signaling in human gastric carcinoma cell MKN-45. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:7262-7270. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Blokzijl A, Dahlqvist C, Reissmann E, Falk A, Moliner A, Lendahl U, Ibáñez CF. Cross-talk between the Notch and TGF-beta signaling pathways mediated by interaction of the Notch intracellular domain with Smad3. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:723-728. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Kurpinski K, Lam H, Chu J, Wang A, Kim A, Tsay E, Agrawal S, Schaffer DV, Li S. Transforming growth factor-beta and notch signaling mediate stem cell differentiation into smooth muscle cells. Stem Cells. 2010;28:734-742. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Tang Y, Urs S, Boucher J, Bernaiche T, Venkatesh D, Spicer DB, Vary CP, Liaw L. Notch and transforming growth factor-beta (TGFbeta) signaling pathways cooperatively regulate vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:17556-17563. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Fu Y, Chang A, Chang L, Niessen K, Eapen S, Setiadi A, Karsan A. Differential regulation of transforming growth factor beta signaling pathways by Notch in human endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19452-19462. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Zavadil J, Cermak L, Soto-Nieves N, Böttinger EP. Integration of TGF-beta/Smad and Jagged1/Notch signalling in epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition. EMBO J. 2004;23:1155-1165. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Itoh F, Itoh S, Goumans MJ, Valdimarsdottir G, Iso T, Dotto GP, Hamamori Y, Kedes L, Kato M, ten Dijke Pt P. Synergy and antagonism between Notch and BMP receptor signaling pathways in endothelial cells. EMBO J. 2004;23:541-551. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Beets K, Huylebroeck D, Moya IM, Umans L, Zwijsen A. Robustness in angiogenesis: notch and BMP shaping waves. Trends Genet. 2013;29:140-149. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Moya IM, Umans L, Maas E, Pereira PN, Beets K, Francis A, Sents W, Robertson EJ, Mummery CL, Huylebroeck D. Stalk cell phenotype depends on integration of Notch and Smad1/5 signaling cascades. Dev Cell. 2012;22:501-514. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Elsharkawy AM, Mann DA. Nuclear factor-kappaB and the hepatic inflammation-fibrosis-cancer axis. Hepatology. 2007;46:590-597. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Faouzi S, Burckhardt BE, Hanson JC, Campe CB, Schrum LW, Rippe RA, Maher JJ. Anti-Fas induces hepatic chemokines and promotes inflammation by an NF-kappa B-independent, caspase-3-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:49077-49082. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Mann DA, Smart DE. Transcriptional regulation of hepatic stellate cell activation. Gut. 2002;50:891-896. [PubMed] |

| 37. | Lang A, Schoonhoven R, Tuvia S, Brenner DA, Rippe RA. Nuclear factor kappaB in proliferation, activation, and apoptosis in rat hepatic stellate cells. J Hepatol. 2000;33:49-58. [PubMed] |

| 38. | Oakley F, Meso M, Iredale JP, Green K, Marek CJ, Zhou X, May MJ, Millward-Sadler H, Wright MC, Mann DA. Inhibition of inhibitor of kappaB kinases stimulates hepatic stellate cell apoptosis and accelerated recovery from rat liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:108-120. [PubMed] |

| 39. | Chen Y, Decker KF, Zheng D, Matkovich SJ, Jia L, Dorn GW. A nucleus-targeted alternately spliced Nix/Bnip3L protein isoform modifies nuclear factor κB (NFκB)-mediated cardiac transcription. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:15455-15465. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Basak S, Kim H, Kearns JD, Tergaonkar V, O'Dea E, Werner SL, Benedict CA, Ware CF, Ghosh G, Verma IM. A fourth IkappaB protein within the NF-kappaB signaling module. Cell. 2007;128:369-381. [PubMed] |

| 41. | Oakley F, Mann J, Ruddell RG, Pickford J, Weinmaster G, Mann DA. Basal expression of IkappaBalpha is controlled by the mammalian transcriptional repressor RBP-J (CBF1) and its activator Notch1. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:24359-24370. [PubMed] |

| 42. | Ang HL, Tergaonkar V. Notch and NFkappaB signaling pathways: Do they collaborate in normal vertebrate brain development and function? Bioessays. 2007;29:1039-1047. [PubMed] |

| 43. | Espinosa L, Inglés-Esteve J, Robert-Moreno A, Bigas A. IkappaBalpha and p65 regulate the cytoplasmic shuttling of nuclear corepressors: cross-talk between Notch and NFkappaB pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:491-502. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Nieto N. Ethanol and fish oil induce NFkappaB transactivation of the collagen alpha2(I) promoter through lipid peroxidation-driven activation of the PKC-PI3K-Akt pathway. Hepatology. 2007;45:1433-1445. [PubMed] |

| 45. | Rashid ST, Humphries JD, Byron A, Dhar A, Askari JA, Selley JN, Knight D, Goldin RD, Thursz M, Humphries MJ. Proteomic analysis of extracellular matrix from the hepatic stellate cell line LX-2 identifies CYR61 and Wnt-5a as novel constituents of fibrotic liver. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:4052-4064. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Shafiei MS, Shetty S, Scherer PE, Rockey DC. Adiponectin regulation of stellate cell activation via PPARγ-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Pathol. 2011;178:2690-2699. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Cheng JH, She H, Han YP, Wang J, Xiong S, Asahina K, Tsukamoto H. Wnt antagonism inhibits hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G39-G49. [PubMed] |

| 49. | Mann J, Chu DC, Maxwell A, Oakley F, Zhu NL, Tsukamoto H, Mann DA. MeCP2 controls an epigenetic pathway that promotes myofibroblast transdifferentiation and fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:705-714, 714. e1-e4. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Okamura M, Kudo H, Wakabayashi K, Tanaka T, Nonaka A, Uchida A, Tsutsumi S, Sakakibara I, Naito M, Osborne TF. COUP-TFII acts downstream of Wnt/beta-catenin signal to silence PPARgamma gene expression and repress adipogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5819-5824. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Mödder UI, Oursler MJ, Khosla S, Monroe DG. Wnt10b activates the Wnt, notch, and NFκB pathways in U2OS osteosarcoma cells. J Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1392-1402. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | Kim HA, Koo BK, Cho JH, Kim YY, Seong J, Chang HJ, Oh YM, Stange DE, Park JG, Hwang D. Notch1 counteracts WNT/β-catenin signaling through chromatin modification in colorectal cancer. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:3248-3259. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 53. | Horvay K, Abud HE. Regulation of intestinal stem cells by Wnt and Notch signalling. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013;786:175-186. [PubMed] [DOI] |