修回日期: 2010-04-19

接受日期: 2011-04-26

在线出版日期: 2011-06-08

目的: 探讨悬浮状态下小鼠拟胚体中定型内胚层的分化比例对其体内小肠吸收细胞分化的影响.

方法: 利用标志分子检测不同阶段胚体中定型内胚层的分化及Activin A对其分化的促进作用. 随后, 接种含高比例定型内胚层的胚体至裸鼠皮下培育移植瘤, 研究移植瘤中吸收细胞的分化.

结果: 培养5 d的胚体中定型内胚层的比例较1、3、7 d高(Gsc: 0.9809±0.1001 vs 0.5435±0.0821, 0.5525±0.0786, 0.2234±0.0425; Tm4sf2: 0.9231±0.1121 vs 0.0017±0.0007, 0.0176±0.0058, 0.6542±0.0742; Gpc1: 0.8639±0.1098 vs 0.5882±0.1027, 0.7112±0.0956, 0.4239±0.0874, 均P<0.05), 50 μg/L的Activin A可使其分化比例进一步升高(均P<0.05). 诱导组胚体细胞所形成的皮下移植瘤中, 小肠吸收细胞标志分子的表达量显著高于对照组(均P<0.05), 且含有较多表达Fabp2的细胞团及腺样结构.

结论: Activin A可通过提高悬浮状态下小鼠拟胚体中定型内胚层的分化比例促进其小肠吸收细胞的体内分化.

引文著录: 邓娜, 于涛, 石柳, 兰绍阳, 周慧敏, 陈浩, 陈其奎. 小鼠拟胚体中定型内胚层的比例对小肠吸收细胞分化的促进作用. 世界华人消化杂志 2011; 19(16): 1686-1692

Revised: April 19, 2010

Accepted: April 26, 2011

Published online: June 8, 2011

AIM: To investigate the effect of inducing the differentiation of definitive endoderm derived from mouse embryonic bodies (EBs) cultured by the hanging drop method in promoting the differentiation of intestinal absorptive cells in vivo.

METHODS: The differentiation of definitive endoderm during EBs formation derived from mouse ES-E14TG2a embryonic stem cells (ESC) and the role of Activin A in promoting its differentiation were monitored by detecting its markers by RT-PCR and fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Subsequently, the EBs with high proportion of definitive endoderm were hypodermically engrafted into the back of NOD/SCID mice to form grafts. The markers for small intestinal absorptive cells, including SI, LPH, and Fabp2, were detected in these grafts by quantitative RT-PCR and immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS: The marker genes for definitive endoderm were more highly expressed in the 5-day EBs than in other stages of EBs (Gsc: 0.9809 ± 0.1001 vs 0.5435 ± 0.0821, 0.5525 ± 0.0786, 0.2234 ± 0.0425; Tm4sf2: 0.9231 ± 0.1121 vs 0.0017 ± 0.0007, 0.0176 ± 0.0058, 0.6542 ± 0.0742; Gpc1: 0.8639 ± 0.1098 vs 0.5882 ± 0.1027, 0.7112 ± 0.0956, 0.4239 ± 0.0874, all P < 0.05). The percentage of definitive endoderm cells in the 5-day EBs induced with 50 μg/L Activin A (SF-A group) was significantly higher than that in controls (all P < 0.05). SI and LPH mRNA expression in the grafts from the SF-A group was significantly higher than that in control groups (all P < 0.05). Immunohistochemical analysis revealed that Fabp2 was expressed in some immature cells without specific structure or adenoid structures in the grafts from the SF-A group.

CONCLUSION: The differentiation of definitive endoderm derived from mouse ESC could be induced with 50 ng/ml Activin A in EBs cultured by the hanging drop method. Increasing the proportion of definitive endoderm in EBs promotes the differentiation of intestinal absorptive cells in vivo.

- Citation: Deng N, Yu T, Shi L, Lan SY, Zhou HM, Chen H, Chen QK. Differentiation of intestinal absorptive cells derived from mouse embryonic bodies can be promoted by inducing the differentiation of definitive endoderm in vivo. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2011; 19(16): 1686-1692

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v19/i16/1686.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v19.i16.1686

胚胎干细胞(embryonic stem cell, ESC)具有自我更新及多向分化的潜能[1]. 小鼠ESC在去除白血病抑制因子(leukemia inhibiting factor, LIF)的培养基中可以形成胚体(embryonic bodies, EBs)[2-4], 并分化为3个胚层的细胞, 其中内胚层细胞包括定型内胚层(标志为Gsc、Tm4sfz、Gpc1及CXCR4)和脏内胚层(标志为Sdc4)[5-10]. Activin A通过激活Nodal通路可促进定型内胚层的分化[5]. 研究显示, 定型内胚层是肠上皮干细胞及各种肠上皮细胞的前体[11-14]. 其中小肠吸收细胞特异表达蔗糖酶异麦芽糖酶(sucrase-isomaltase, SI)、乳糖酶根皮苷水解酶(lactase phlorizin hydrolase, LPH)及肠脂肪吸收蛋白(intestinal fatty acid-binding protein 2, Fabp2)[15-18]. 目前, Activin A对定型内胚层的分化促进研究主要针对贴壁培养的EBs细胞, 而Activin A能否提高悬滴培养状态下EBs中的定型内胚层比例, 以及通过这一处理, 能否提高EBs在体内分化为小肠吸收细胞的能力还有待探讨.

(1)ESC培养基: 以高糖DMEM为基础培养基, 各添加物的终浓度为: 100 mL/L胎牛血清, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 0.12% NaHCO3, 0.1 mmol/L非必需氨基酸, 0.1 mmol/L β-巯基乙醇, 1 000 kU/L LIF(购置于Chemicon公司). EBs培养基(FCS组): 以高糖DMEM为基础培养基, 各添加物的终浓度为: 100 mL/L胎牛血清, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 0.12% NaHCO3, 0.1mmol/L非必需氨基酸, 0.1mmol/L β-巯基乙醇. ActivinA无血清培养基(SF-A): 以高糖DMEM为基础培养基, 各添加物的终浓度为: 10% KnockoutTM血清替代物(KSR), 10 mmol/L HEPES, 0.12% NaHCO3, 0.1 mmol/L非必需氨基酸, 0.1 mmol/L β-巯基乙醇, 50 μg/L Activin A(购置于R&D公司). 无血清对照培养基(SF): 以高糖DMEM为基础培养基, 使各添加物的终浓度为: 10% KSR, 10 mmol/L HEPES, 0.12% NaHCO3, 0.1 mmol/L非必需氨基酸, 0.1mmol/L β-巯基乙醇. 兔抗小鼠Fabp2多克隆抗体购置于Cayman公司; (2)梯度PCR仪购于美国PE公司. Beckman Coulter EPICS ALTRA流式细胞仪购于Beckman Coulte公司. 倒置显微镜购于LECIA公司; (3)小鼠ES-E14TG2a系ESC, 购于American Type Culture Collection(ATCC). NOD/SCID免疫缺陷小鼠, 购于中山大学北校区实验动物中心(广州), 雌雄各半, 周龄6-8 wk.

1.2.1 EBs的悬滴培养: 制备ESC的细胞悬液, 分别使用SF-A、SF及EBs培养基调整细胞浓度为1.0×109/L左右, 在90 mm培养皿皿盖上使用定量移液器接种细胞悬液液滴, 每滴32 μL, 翻转皿盖并盖合至皿上, 放入37 ℃, 50 mL/L CO2的细胞培养箱中. 每日进行换液, 每次每个液滴更换培养基25 μL.

1.2.2 利用RT-PCR检测EBs悬滴培养状态下内胚层的分化情况: 从各组不同时间的EBs中提取RNA, 小鼠各内胚层标志分子的PCR引物序列(表1). RT-PCR采用半定量分析, 以β-actin作为内参, 结果以相对灰度表示.

| 基因名称 | 引物序列 | 目的片段大小(bp) |

| Tm4sf2 | 上游: 5'-AGA ATG CCA CAC ACC TTT CC-3' | 443 |

| 下游: 5'-TTC GTT TCC CTT CCA CAC TC-3' | ||

| Gsc | 上游: 5'-GCC GAG AAG TGG AAC AAG AC-3' | 210 |

| 下游: 5'-CAG CTA GCT CCT CGT TGC TT-3' | ||

| Gpc1 | 上游: 5'-GGT CAA TGA GAC CTG GCA CT-3' | 272 |

| 下游: 5'-GAA GAT GGA GCC TTG ACA GC-3' | ||

| Sdc4 | 上游: 5'-GTG AGT TTT CGT GTG GCT GA-3' | 342 |

| 下游: 5'-AGG GAG ACA AGC AAA GCT GA-3' | ||

| β-actin | 上游: 5'-GTC CAC CTT CCA GCA GAT GT-3' | 620 |

| 下游: 5'-CCT GGG CCA TTC AGA AAT TA-3' |

1.2.3 流式细胞仪分析SF-A诱导组和对照组EBs中定型内胚层的分化情况: 用胰酶消化各组不同阶段的EBs, 制备单细胞悬液, 用PE标记的CXCR4抗体(购于R&D公司)标记细胞, 选择488 nm激光测定第1、3、5、7天各组EBs中CXCR4的表达, 比较SF-A诱导组和对照组中定型内胚层细胞的比例有无差别.

1.2.4 利用定量RT-PCR方法检测移植瘤中SI和LPH mRNA表达的相对量: 分别将未分化的ESC以及在SF-A、SF、EBs培养基中培养5 d的EBs皮下注射至NOD/SCID免疫缺陷小鼠背部, 形成移植瘤. PCR引物序列设计(表2). 采用ΔΔCt的统计方法, 以β-actin作为内参, 以ESC组的结果为对照.

| 基因名称 | 引物序列 | 目的片段大小(bp) |

| SI | 上游: 5'-GGG TCC AGC TTT TAT GGT GA-3' | 213 |

| 下游: 5'-TAT GTG TTC TGT GCC GGT TC-3' | ||

| LPH | 上游: 5'-CAC TTT GTG AAC CGC TCT GA-3' | 297 |

| 下游: 5'-GGA GCG CTT GCA GTA TTT GT-3' | ||

| β-actin | 上游: 5'-GTC CAC CTT CCA GCA GAT GT-3' | 620 |

| 下游: 5'-CCT GGG CCA TTC AGA AAT TA-3' |

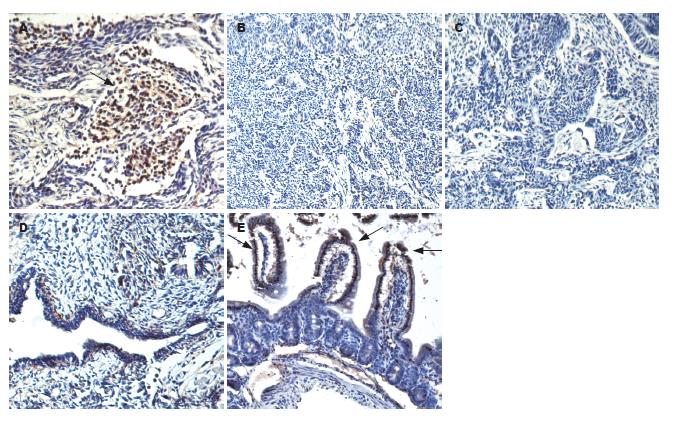

1.2.5 免疫组织化学测定移植瘤中Fabp2的表达: 免疫组织化学采用链霉菌抗生物素蛋白-过氧化物酶联结法, 测定各组移植瘤中Fabp2(抗体1:200稀释)的表达, 并以正常小鼠小肠作为阳性对照, 用DAB显色液显色, 苏木素复染.

统计学处理 所有资料统计均采用SAS8.1统计软件分析, 计量资料以mean±SD表示, 计数资料以百分率表示, 均数的比较采用t检验, 率的比较采用χ2检验, P<0.05为差别有统计学意义.

Gsc在1、3、5、7 d EBs中表达的相对灰度分别为0.5435±0.0821、0.5525±0.0786、0.9809±0.1001、0.2234±0.0425(n = 3); Tm4sf2分别为0.0017±0.0007、0.0176±0.0058、0.9231±0.1121、0.6542±0.0742(n = 3); Gpc1分别为0.5882±0.1027、0.7112±0.0956、0.8639±0.1098、0.4239±0.0874(n = 3). 以上结果显示, 第5天EBs中各定型内胚层标志基因的表达量显著高于其他阶段的EBs[5 d EBs vs 1 d EBs: t = 5.852, P = 0.005(Gsc); t = 14.236, P<0.001(Tm4sf2); t = 3.176, P = 0.034(Gpc1). 5 d EBs vs 3 d EBs: t = 5.830, P = 0.004(Gsc); t = 13.972, P<0.001(Tm4sf2); t = 1.817, P = 0.041(Gpc1). 5 d EBs vs 7 d EBs: t = 12.065, P<0.001(Gsc); t = 3.465, P = 0.026(Tm4sf2); t = 5.430, P = 0.006(Gpc1). 图2]. 而脏内胚层标志基因Sdc4在1、3、5、7 d EBs中表达的相对灰度分别为0.0235±0.0051、0.1027±0.0226、0.5899±0.0678、0.8021±0.0877(n = 3), 在第7天EBs中表达显著增高(7 d EBs vs 1 d EBs: t = 15.351, P<0.001; 7 d EBs vs 3 d EBs: t = 13.376, P<0.001; 7 d EBs vs 1 d EBs: t = 3.316, P = 0.029. 图2).

SF-A组中CXCR4+细胞在第1、3、5、7天EBs中的比例分别为10.40%±2.63%、29.10%±2.41%、41.90%±4.21%、26.70%±2.36%; SF组中分别为4.50%±1.37%、7.30%±1.84%、17.50%±2.90%、12.80%±3.88%; FCS组中分别为8.80%±3.68%、24.50%±3.76%、33.40%±2.87%、16.50%±3.36%. 根据上述结果, SF-A组第5天的EBs中定型内胚层比例显著高于其他组及其他分化阶段(n = 3, SF-A组: 5 d EBs vs 1 d EBs: t = 11.009, P<0.001; 5 d EBs vs 3 d EBs: t = 4.580, P = 0.010; 5 d EBs vs 7 d EBs: t = 5.468, P = 0.005. 5 d EBs: SF-A组 vs SF组: t = 8.273, P = 0.001; SF-A组 vs FCS组: t = 2.884, P = 0.045. 图3).

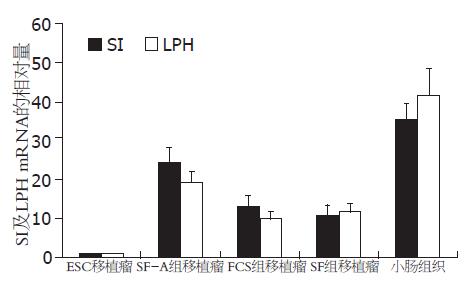

各组第5天的EBs细胞接种至NOD/SCID小鼠皮下后形成移植瘤. 以ESC移植瘤为参照, SI在SF-A组、FCS组、SF组及小鼠小肠组织中mRNA的相对量分别为24.5±3.9、13.2±2.7、10.9±2.5及35.6±4.1; LPH mRNA的相对量分别为19.4±2.8、9.9±1.8、11.8±2.0及41.7±6.8. 结果显示, 经Activin A诱导后悬滴培养5 d的EBs细胞所形成的移植瘤中, SI和LPH的表达均显著高于对照组[n = 3, SF-A组 vs FCS组: t = 4.126, P = 0.015(SI); t = 4.943, P = 0.008(LPH). SF-A组 vs SF组: t = 5.085, P = 0.007(SI); t = 3.826, P = 0.019(LPH), 图4].

SF-A组移植瘤组织切片中Fabp2的表达较多, 且多表达于未定型细胞团及腺样结构中. 而对照组中可见较多的神经管样结构, 不表达Fabp2(图5).

ESC具有增殖、自我更新及多向分化的潜能[1]. ESC在体内、外可以诱导分化为几乎所有的成体组织细胞[19], 这一强大的分化能力为利用前体细胞移植修复组织损伤和改善器官功能提供了一个理想的细胞来源, 其诱导分化过程具有很高的理论研究意义及应用前景. ESC的体外诱导分化是目前生物领域研究的热点, 国内外研究报道将ESC诱导分化为心肌细胞[20-22]、神经细胞[23-25]、肝细胞[26,27]、胰岛素分泌细胞[28,29]等较多, 但将ESC诱导分化为小肠上皮细胞的文献报道较少.

小鼠的ESC可以在体外形成EBs, 并进行内、中、外3个胚层细胞的分化. EBs的悬滴培养是体外模拟囊胚中内细胞团悬浮分化的理想模型, 通过这一特殊的培养方法可以模拟早期胚胎中3个胚层的发育[30], 为内胚层细胞的分化研究提供了有效的手段[31]. 本次研究采用通用的悬滴法培养EBs, 测定第1、3、5、7天定型内胚层标志基因Gsc、Tm4sf2及Gpc1的表达情况, 结果发现各标志分子的表达在第5天的EBs中达到高峰, 随后表达逐渐减低, 提示在维持悬滴培养的状态下第5天的EBs可分化为较多的定型内胚层细胞. 由于脏内胚层的分化在时间上与定型内胚层相近, 但与肠上皮细胞的分化无关, 因此, 本次研究对EBs中脏内胚层的伴随分化也进行了观察. 结果发现, 脏内胚层标志基因Sdc4在EBs悬滴培养过程中逐渐升高, 并于第7天达高峰, 呈现出与定型内胚层不同的分化特征. 这些结果与其他相关研究基本一致[5-7]. 根据以上实验结果, 可以认为悬滴培养下第5天的EBs中定型内胚层分化较多, 是研究其体内分化的理想状态.

Activin A因子是TGF-β家族的一员, 作用于细胞表面的Nodal信号通路受体, 并激活Nodal通路[32,33], 可以有效诱导ESC分化为定型内胚层[5-7]. 在既往研究中, EBs在形成早期(24 h左右)经消化分散后, 加入含Activin A的培养基进行贴壁生长, 以促进定型内胚层的诱导分化[5-7]. 本次研究不同之处是[5-7,34-36], 为了保持EBs更好的自然分化状态, 在加入Activin A后EBs继续采用悬滴法进行悬浮培养, 同时用KSR替代培养基中的胎牛血清, 以减少血清中促分化成分对Activin A诱导的干扰. 结果显示, 以CXCR4作为定型内胚层的标志分子, Activin A诱导组中CXCR4+细胞的比例明显增加. 在Activin A诱导分化后的第5天, EBs中CXCR4+细胞的比例达41.90%±3.21%, 显著高于对照组.

本次研究观察了经50 μg/L Activin A诱导分化5 d后含高比例定型内胚层细胞EBs在裸鼠体内的分化情况. 结果显示, 与ESC和同阶段对照组EBs所形成的移植瘤相比, SF-A组移植瘤中小肠吸收细胞的标志分子SI、LPH的表达明显升高, 显著高于对照组. 同时, 组织学结果显示SF-A组移植瘤中含有较多的腺体结构, 且表达另一成熟小肠吸收细胞的标志分子Fabp2. 以上结果证明, Activin A诱导后的EBs在体内具备更高的肠上皮吸收细胞的分化能力.

总之, 在维持悬浮培养的状态下, Activin A可以提高EBs中定型内胚层的分化比例, 利用此处理方法所获得的第5天EBs在体内具有更高的肠上皮吸收细胞的分化能力, 这一结果为研究前体细胞移植修复肠上皮损伤提供了有力的实验基础.

小鼠胚胎干细胞在去除白血病抑制因子的培养基中可形成胚体, 并分化为内、中、外三个胚层的细胞. 内胚层细胞包括定型内胚层和脏内胚层, 前者是肠上皮干细胞及各种肠上皮细胞的前体.

伍晓汀, 主任医师, 四川大学华西医院胃肠外科中心; 朱亮, 副教授, 大连医科大学生理教研室

该领域的研究热点主要集中在胚胎干细胞的体内和体外分化.

Kubo等报道, 加入Activin A的培养基可促进胚胎干细胞向定型内胚层分化.

国内外研究将胚胎干细胞诱导分化为小肠上皮细胞较少. 目前, Activin A对定型内胚层的分化促进研究主要针对贴壁培养的胚体细胞, 本次研究加入Activin A后胚体培养仍采取悬滴培养, Activin A诱导后的胚体在体内具备更高的肠上皮吸收细胞的分化能力.

在维持悬浮培养的状态下, Activin A可以提高胚体中定型内胚层的分化比例, 且第5天胚体在体内具有更高的肠上皮吸收细胞的分化能力, 为研究前体细胞移植修复肠上皮损伤提供了坚实的实验基础.

本文学术性和创新性较好, 有一定的临床借鉴意义和应用前景.

编辑: 李薇 电编:李薇

| 3. | Williams RL, Hilton DJ, Pease S, Willson TA, Stewart CL, Gearing DP, Wagner EF, Metcalf D, Nicola NA, Gough NM. Myeloid leukaemia inhibitory factor maintains the developmental potential of embryonic stem cells. Nature. 1988;336:684-687. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Smith AG, Heath JK, Donaldson DD, Wong GG, Moreau J, Stahl M, Rogers D. Inhibition of pluripotential embryonic stem cell differentiation by purified polypeptides. Nature. 1988;336:688-690. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Yasunaga M, Tada S, Torikai-Nishikawa S, Nakano Y, Okada M, Jakt LM, Nishikawa S, Chiba T, Era T, Nishikawa S. Induction and monitoring of definitive and visceral endoderm differentiation of mouse ES cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1542-1550. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Kubo A, Shinozaki K, Shannon JM, Kouskoff V, Kennedy M, Woo S, Fehling HJ, Keller G. Development of definitive endoderm from embryonic stem cells in culture. Development. 2004;131:1651-1662. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Gouon-Evans V, Boussemart L, Gadue P, Nierhoff D, Koehler CI, Kubo A, Shafritz DA, Keller G. BMP-4 is required for hepatic specification of mouse embryonic stem cell-derived definitive endoderm. Nat Biotechnol. 2006;24:1402-1411. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Shiraki N, Umeda K, Sakashita N, Takeya M, Kume K, Kume S. Differentiation of mouse and human embryonic stem cells into hepatic lineages. Genes Cells. 2008;13:731-746. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Shiraki N, Yoshida T, Araki K, Umezawa A, Higuchi Y, Goto H, Kume K, Kume S. Guided differentiation of embryonic stem cells into Pdx1-expressing regional-specific definitive endoderm. Stem Cells. 2008;26:874-885. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Lu CC, Brennan J, Robertson EJ. From fertilization to gastrulation: axis formation in the mouse embryo. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2001;11:384-392. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Abud HE, Watson N, Heath JK. Growth of intestinal epithelium in organ culture is dependent on EGF signalling. Exp Cell Res. 2005;303:252-262. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Barker N, van de Wetering M, Clevers H. The intestinal stem cell. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1856-1864. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Marshman E, Booth C, Potten CS. The intestinal epithelial stem cell. Bioessays. 2002;24:91-98. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Quinlan JM, Yu WY, Hornsey MA, Tosh D, Slack JM. In vitro culture of embryonic mouse intestinal epithelium: cell differentiation and introduction of reporter genes. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:24. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Jessup JM, Lavin PT, Andrews CW, Loda M, Mercurio A, Minsky BD, Mies C, Cukor B, Bleday R, Steele G. Sucrase-isomaltase is an independent prognostic marker for colorectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:1257-1264. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Weiss EP, Brown MD, Shuldiner AR, Hagberg JM. Fatty acid binding protein-2 gene variants and insulin resistance: gene and gene-environment interaction effects. Physiol Genomics. 2002;10:145-157. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Yu T, Chen QK, Gong Y, Xia ZS, Royal CR, Huang KH. Higher expression patterns of the intestinal stem cell markers Musashi-1 and hairy and enhancer of split 1 and their correspondence with proliferation patterns in the mouse jejunum. Med Sci Monit. 2010;16:BR68-BR74. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Solter D. From teratocarcinomas to embryonic stem cells and beyond: a history of embryonic stem cell research. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:319-327. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Wang Y, Fan Y, Puga A. Dioxin exposure disrupts the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into cardiomyocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2010;115:225-237. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Chen M, Lin YQ, Xie SL, Wu HF, Wang JF. Enrichment of cardiac differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells by optimizing the hanging drop method. Biotechnol Lett. 2011;33:853-858. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Neri T, Merico V, Fiordaliso F, Salio M, Rebuzzini P, Sacchi L, Bellazzi R, Redi CA, Zuccotti M, Garagna S. The differentiation of cardiomyocytes from mouse embryonic stem cells is altered by dioxin. Toxicol Lett. 2011;202:226-236. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Dolmazon V, Alenina N, Markossian S, Mancip J, van de Vrede Y, Fontaine E, Dehay C, Kennedy H, Bader M, Savatier P. Forced expression of LIM homeodomain transcription factor 1b enhances differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into serotonergic neurons. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:301-311. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Taléns-Visconti R, Sanchez-Vera I, Kostic J, Perez-Arago MA, Erceg S, Stojkovic M, Guerri C. Neural differentiation from human embryonic stem cells as a tool to study early brain development and the neuroteratogenic effects of ethanol. Stem Cells Dev. 2011;20:327-339. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Zhou M, Li P, Tan L, Qu S, Ying QL, Song H. Differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into hepatocytes induced by a combination of cytokines and sodium butyrate. J Cell Biochem. 2010;109:606-614. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Naujok O, Francini F, Picton S, Bailey CJ, Lenzen S, Jörns A. Changes in gene expression and morphology of mouse embryonic stem cells on differentiation into insulin-producing cells in vitro and in vivo. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2009;25:464-476. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Kinder SJ, Tsang TE, Wakamiya M, Sasaki H, Behringer RR, Nagy A, Tam PP. The organizer of the mouse gastrula is composed of a dynamic population of progenitor cells for the axial mesoderm. Development. 2001;128:3623-3634. [PubMed] |

| 31. | Banerjee M, Bhonde RR. Application of hanging drop technique for stem cell differentiation and cytotoxicity studies. Cytotechnology. 2006;51:1-5. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Ling N, Ying SY, Ueno N, Shimasaki S, Esch F, Hotta M, Guillemin R. Pituitary FSH is released by a heterodimer of the beta-subunits from the two forms of inhibin. Nature. 1986;321:779-782. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Lewis SL, Tam PP. Definitive endoderm of the mouse embryo: formation, cell fates, and morphogenetic function. Dev Dyn. 2006;235:2315-2329. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Qu XB, Pan J, Zhang C, Huang SY. Sox17 facilitates the differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells into primitive and definitive endoderm in vitro. Dev Growth Differ. 2008;50:585-593. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Arufe MC, Lu M, Lin RY. Differentiation of murine embryonic stem cells to thyrocytes requires insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;381:264-270. [PubMed] [DOI] |