修回日期: 2007-01-28

接受日期: 2007-02-08

在线出版日期: 2007-05-18

目的: 研究肝脏缝隙连接细胞间通讯(GJIC)对大鼠体内肝卵圆细胞(HOC)增殖的影响.

方法: 健康♂Wistar大鼠, 随机分成对照组(n = 6)、模型组、苯巴比妥(Phenobarbital, PB)组. 模型组大鼠按每天20 mg/kg剂量灌喂2-AFF, 连续4 d, 第5天不灌喂行2/3肝切除, 术后次日按每天20 mg/kg剂量继续灌喂5 d (2-AFF/PH); PB组予以0.8 g/L PB饮水7 d, 第8天按模型组处理, 0.8 g/L PB饮水持续至实验结束. 模型组、PB组在术后4 h, 4, 8, 12和16 d随机取6只大鼠检测. 采用组织病理技术观察肝组织的形态学变化; 免疫组化和细胞形态学方法计数HOC; 切开标记/染料示踪技术(incision loading/dye transfer, IL/DT)技术确定GJIC; 免疫组化及RT-PCR技术检测CX32蛋白及mRNA表达; 免疫组化、Western blot及RT-PCR技术分析CX43蛋白及mRNA水平.

结果: 对照组及模型组和PB组4 h未见HOC增殖. 模型组4 d汇管区有HOC增殖反应, 8 d HOC增殖达峰值, 12 d HOC从汇管区向肝实质内浸润, 16 d HOC增殖较12 d减少. 与模型组比较PB组4-16 d各时点HOC明显增加(P<0.01); IL/DT显示各时点模型组大鼠肝脏GJIC均低于对照组(P<0.01), 与模型组比较PB组各时点GJIC进一步降低(P<0.01); 模型组、PB组各时点CX32的表达低于对照组(P<0.05), 与模型组比较PB组CX32表达在4 h, 12, 16 d时点减少(P<0.05), 在4, 8 d时点表达增多(P<0.05; 模型组4 h-16 d时点CX32 mRNA水平分别为对照组的0.82±0.13, 0.33±0.11, 0.51±0.13, 0.68±0.14, 1.12±0.18倍, 与模型组比较PB组4 h时点无显著差异(P>0.05), 4-16 d时点明显升高(P<0.05). 模型组4 h-16 d各时点CX43蛋白表达分别为对照组的1.14±0.17, 3.87±0.35, 5.28±0.48, 2.96±0.33, 2.12±0.19倍, 与模型组比较PB组CX43蛋白4 h上调(P>0.05), 4-16 d明显减少(P<0.05). 模型组4 h-16 d各时点CX43 mRNA水平分别为对照组的1.09±0.16, 2.82±0.23, 5.46±0.58, 3.34±0.64, 0.91±0.11倍. 与模型组比较PB组各时点CX43 mRNA表达上调(P<0.05).

结论: 改变大鼠2-AAF/PH模型肝脏CX32、CX43的时空表达模式, 降低肝脏肝细胞及HOC与其偶联细胞的GJIC, 可解除HOC生长抑制, 促进HOC的增殖.

引文著录: 李学东, 傅华群, 李少华, 尚西亮, 邢宏松, 胡鹏. 肝脏GJIC对大鼠体内肝卵圆细胞增殖的影响. 世界华人消化杂志 2007; 15(14): 1583-1590

Revised: January 28, 2007

Accepted: February 8, 2007

Published online: May 18, 2007

AIM: To investigate the effect of gap junction intercellular communication (GJIC) in rat liver on the proliferation of hepatic oval cells (HOC) in vivo.

METHODS: Male Wistar rats were randomized into control group (n = 6), model group and phenobarbital (PB) group. HOC proliferation was induced in the rats of model group: 9 days of treatment with 2-AAF, 20 mg/kg per day by gavage, interrupted on day 5 to perform a 70% hepatectomy (2-AAF/PH). The rats in PB group were administered with PB (0.8 g/L, till the end of experiment) in drinking water, and on the 8th day they received the same treatment as model group. The rats in model and PB group were sacrificed and necropsied at the 4th hour, on the 4th, 8th, 12th and 16th day (6 rats at each time point) followed hepatectomy. The morphological changes of liver tissues were observed by pathological examination and the proliferation of HOC was counted using immunohistochemistry and morphological recognition. GJIC was confirmed by incision loading/dye transfer (IL/DT), and the levels of CX32 protein and mRNA were detected by immunohistochemistry and reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), respectively. The expression of CX43 protein and mRNA were determined by immunohistochemistry, Western blot and RT-PCR, respectively.

RESULTS: No HOC proliferation was seen in the rat liver of control, 4-hour model and PB group. HOC appeared at portal area in model group on day 4, increased to the peak on day 8, intensely proliferated from the portal spaces and invaded the liver parenchyma on day 12, and decreased on day 16 as compared with day 12. HOC proliferation had a significant increase in PB group (from day 4 to 16) as compared with that in model group. The distance of dye transfer in model group (4 h, 4, 8, 12, 16 d) was significantly reduced in comparison with that in control group, and moreover, it was further decreased in PB group. The signal number of CX32 in the rat liver of model and PB groups were reduced as compared with that in control group (P < 0.05), and there was also significant differences between model and PB group (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01). The expression of CX32 mRNA in model group at the 4th hour, on the 4th, 8th, 12th and 16th day was 0.82 ± 0.13, 0.33 ± 0.11, 0.51 ± 0.13, 0.68 ± 0.14 and 1.12 ± 0.18 folds of that in control group, respectively. As compared with that in model group, the level of CX32 mRNA expression in PB group had no statistical difference at the 4th hour (P > 0.05), but had a significant increase on day 4 to 16 (P < 0.05). The expression of CX43 protein in the liver of model group at the 4th hour, on the 4th, 8th, 12th and 16th day was 1.14 ± 0.17, 3.87 ± 0.35, 5.28 ± 0.48, 2.96 ± 0.33 and 2.12 ± 0.19 folds of that in control group, respectively. As compared with that in model group, the quantity of CX43 protein in PB group had no statistical difference at the 4th hour (P > 0.05), but had a significant decrease on day 4 to 16 (P < 0.05). The level of CX43 mRNA expression in model group at the 4th hour, on the 4th, 8th, 12th and 16th day was 1.09 ± 0.16, 2.82 ± 0.23, 5.46 ± 0.58, 3.34 ± 0.64 and 0.91 ± 0.11 folds of that in control group, respectively. As compared with that in model group, the level of CX43 mRNA in PB group was increased (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION: The GJIC of hepatocyte and HOC can be decreased by altering the spatial and temporal expression patterns of CX in rat liver after 2-AAF/PH, which leads to the acceleration of HOC proliferation.

- Citation: Li XD, Fu HQ, Li SH, Shang XL, Xing HS, Hu P. Effects of gap junction intercellular communication in rat liver on the proliferation of hepatic oval cells in vivo. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2007; 15(14): 1583-1590

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v15/i14/1583.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v15.i14.1583

肝卵圆细胞(hepatic oval cells, HOC)是肝干细胞的子代细胞, 对其增殖、分化的研究多集中于细胞因子及细胞外基质的调控[1-5]. 由于缝隙连接细胞间通讯(gap junction intercellular communication, GJIC)是细胞间重要的信息交流形式, 可调节组织细胞的生长、增殖与分化[6-8]. 本实验采用苯巴比妥(phenobarbital, PB)抑制大鼠肝脏GJIC, 并构建HOC增殖模型(2-乙酰氨基芴喂食+2/3肝切除术2-acetylaminofluorene/ two-thirds partial hepatectomy, 2-AAF/PH), 以肝脏GJIC功能为本, 从缝隙连接蛋白(connexin, CX)32, 43表达的角度探讨肝脏GJIC对体内HOC的影响.

健康♂Wistar大鼠, 体质量150 g左右, 由南昌大学医学院动物科学部提供; 苯巴比妥(广东邦民制药有限公司); 2-乙酰氨基芴(2-acetylaminofluorene, 2-AAF; Sigma公司); 聚乙二醇(PEG400, 上海试剂一厂); 小鼠抗大鼠OV-6单克隆抗体(美国S Sell实验室); Mouse anti-human CX43抗体、Mouse anti-human CX32抗体(Santa Cruz公司); 抗小鼠SP试剂盒(北京中杉金桥生物技术有限公司); Lucifer yellow(LY)、Rhodamine D(Sigma公司); TRIzol(Invitrogen公司); Oligo(dT)15(北京天为时代公司); dNTPs(BM公司); M-MLV逆转录酶(Promega公司); 大鼠CX43, CX32, GADPH引物(上海生工公司).

1.2.1 动物处理及标本采集: 大鼠首先随机分成对照组、模型组和PB组. 2-AFF用分子量为400 Da的PEG溶解成浓度为4 g/L的溶液, 模型组大鼠每天按20 mg/kg剂量灌喂, 连续4 d, 第5天不灌喂, 在乙醚吸入麻醉下行2/3肝切除, 术后次日按每天20 mg/kg剂量继续灌喂5 d(2-AFF/PH). PB组大鼠参考文献[9]予以0.8 g/L PB饮水7 d, 第8天按模型组处理, 0.8 g/L PB饮水持续至取材. 模型组和PB组大鼠在术后4 h, 4, 8, 12和16 d随机取6只检测. 对照组大鼠未预特殊处理, 作正常对照(n = 6. 大鼠在乙醚吸入麻醉后剖腹, 取0.5 cm×0.5 cm×0.3 cm的右肝中叶, 置中性缓冲福尔马林液固定, 备行HE染色及免疫组化; 取1.0 cm×1.0 cm×1.0 cm的右肝中叶, 行切开标记/染料示踪技术(incision loading/dye transfer, IL/DT)分析; 剪右肝中叶成50-100 mg的小块若干, 分置液氮保存, 提取总蛋白及RNA.

1.2.2 免疫组织化学染色: 石蜡切片经常规脱蜡水化后, 抗原热修复15-20 min; 按SP免疫组化试剂盒说明书操作, 一抗工作液浓度分别为: OV-6 1∶80, CX32 1∶250, CX43 1∶300. 磷酸盐(PBS)缓冲液代替一抗做空白对照.

1.2.3 IL/DT: 方法参考文献[10-13]在新鲜肝组织表面上滴少许(约200 μL)含有LY(5 g/L)和RhD(5 g/L)染料的PBS缓冲液, 用刀片作3-4个深1 mm、长7-8 mm的切口, 再于切口内注入少许染料, 室温下染料扩散3 min, 后用PBS洗3次, 每次1 min, 再将组织放入40 g/L福尔马林液内避光过夜, 石蜡包埋, 垂直切口作5 μm厚的石蜡切片, 于免疫荧光显微镜下测量LY的净染色传输距离.

1.2.4 图像分析: 每张OV-6免疫组织化学切片选取5个互不重叠且肝卵圆细胞增殖最明显的视野, 在400倍显微镜下对符合肝卵圆细胞特征(体积较小约为肝细胞直径的1/3-1/5, 细胞核呈卵圆形, 胞质较少, 略嗜碱性)且OV-6染色阳性的细胞进行计数, 其平均值作为此标本卵圆细胞增殖的数量; 每张CX32免疫组织化学切片于400倍镜下随机取5个视野, 计算CX32阳性信号数与视野内的肝细胞数之比, 作为该标本CX32的信号数; 每张IL/DT切片随机在免疫荧光显微镜下取5处测量LY和RhD的染色区域. LY的净染色区分析GJIC. 其均值作为GJIC结果.

1.2.5 CX43蛋白Western blot分析: 取100 mg肝组织在冰冻下研成粉末, 加入1.0 mL裂解缓冲液匀浆, 12 000 g 4℃, 离心20 min, 取上清液Folin-酚法进行蛋白质的定量-70℃冷冻备用. 取50 μg总蛋白加入上样缓冲液煮沸5 min变性, 经SDS-PAGE凝胶电泳, 电泳后将蛋白转至硝酸纤维素膜上; 脱脂奶封闭150 min, 与1∶1000稀释的CX43抗体4℃孵育过夜, 再与1∶500稀释的二抗孵育2 h, 与化学发光试剂ECL温浴1 min后曝光、显影和定影. X光胶片扫描后, 在医学图形分析系统上进行分析. 计算方法为: 所得CX43蛋白带的综合灰度除以对照组样本的综合灰度值即为表达量.

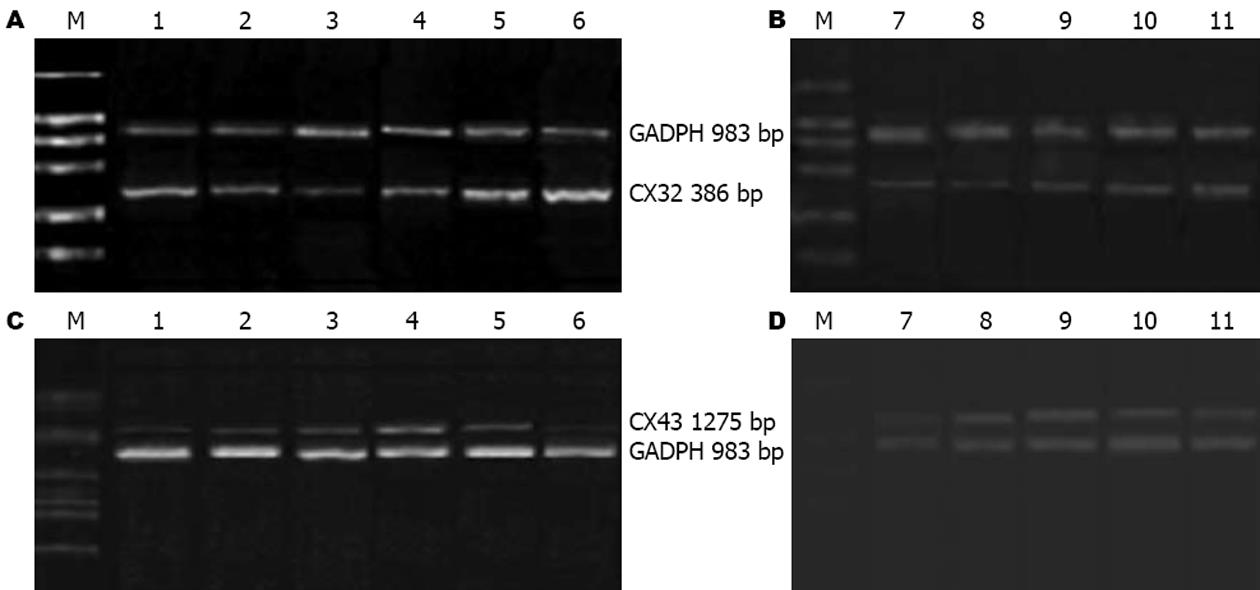

1.2.6 RT-PCR检测肝组织CX32、CX43 mRNA表达: 取肝组织50-100 mg, 总RNA提取用TRIzol试剂按说明操作进行. cDNA采用M-MLV RT kit(Promaga, USA)试剂盒进行. CX32, CX43和GADPH引物设计利用Primer Premier 5.0软件(PremierBiosoft, CA)设计完成. 引物序列及长度见表1. PCR反应条件: 94℃预变性5 min, 94℃变性40 s, 58℃退火45 s(CX32, GADPH), 63℃退火45 s(CX43), 72℃延伸1 min, 30个循环后, 72℃延伸10 min.

| 基因 | 正义(5'-3') | 反以(5'-3') | 产物长度(bp) |

| GADPH | TGAAGGTCGGTGTCAACGGATTTGGC | CATGTAGGCCATGAGGTCCACCAC | 983 |

| CX32 | CTGCTCTACCCGGGCTATGC | CAGGCTGAGCATCGGTCGCTCTT | 386 |

| CX43 | TGGGGGAAAGGCGTGAG | CTGCTGGCTCTGCTGGAAGGT | 1275 |

统计学处理 数据以mean±SD表示, 组间比较用方差分析. P<0.05被认为差异具有统计学意义.

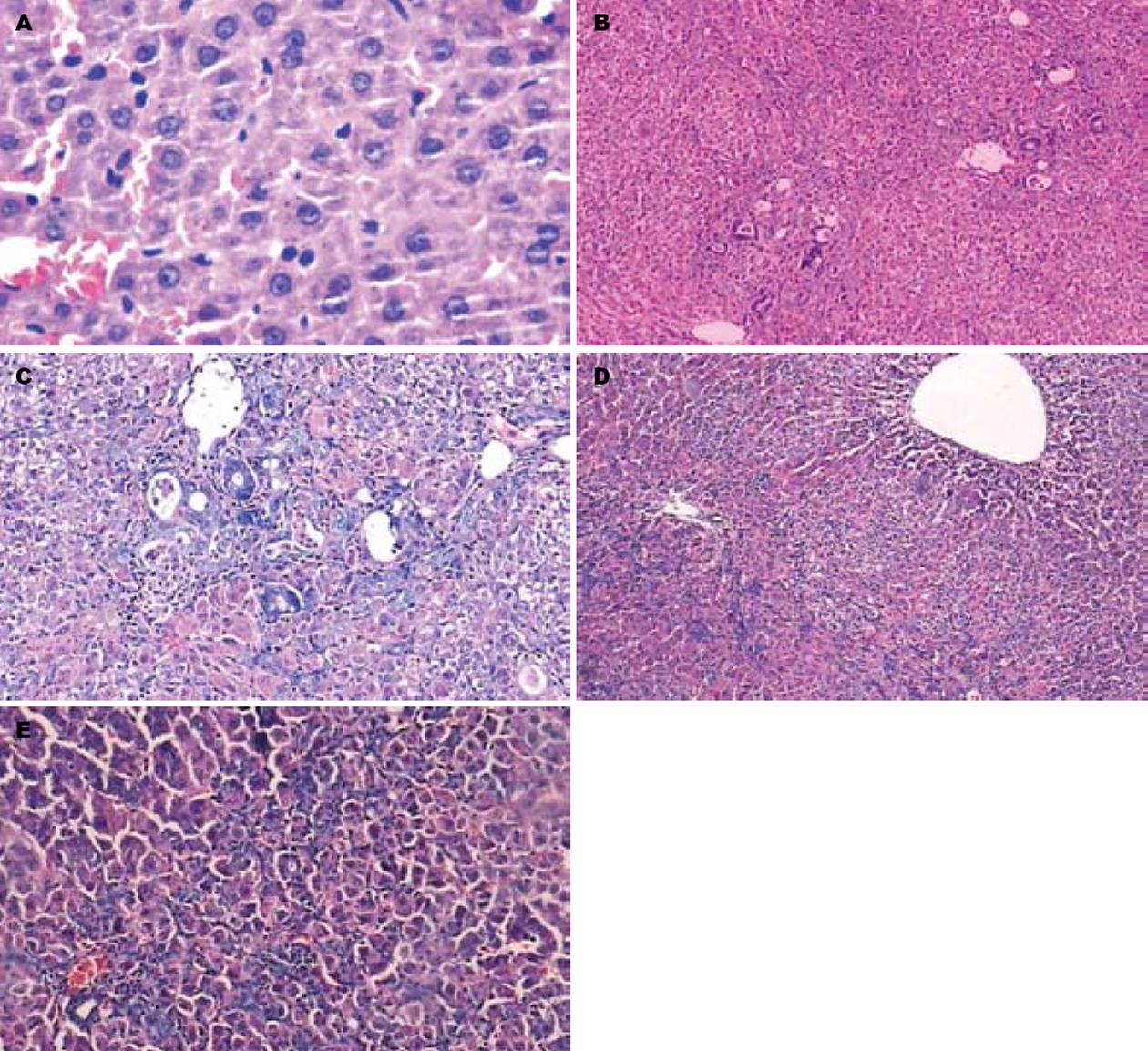

对照组肝组织结构完整, 肝细胞索排列正常, 未见增殖反应. 模型组、PB组4 h肝组织结构无明显破坏及增殖反应. 模型组4, 8 d肝索结构紊乱, 肝细胞水肿、变性坏死, 第4天汇管区有增殖反应, 第8天增殖反应明显, 并向小叶中央区穿插生长; 12 d肝细胞水肿、坏死减轻多由增殖细胞替代, 增生已连成片, 增生反应减少; 16 d仍可见增殖反应. PB组4-16 d也可见肝索结构破坏, 汇管区增殖细胞并向肝内浸润重建损伤肝脏过程, 与模型组比较PB组各时点增殖反应明显, 持续时间长. 增殖细胞体积较小、约为肝细胞直径的1/3-1/5, 细胞核呈卵圆形, 胞质较少, 略嗜碱性、大小分布不均匀、呈簇状分布, 从汇管区向肝小叶中央浸润(图1).

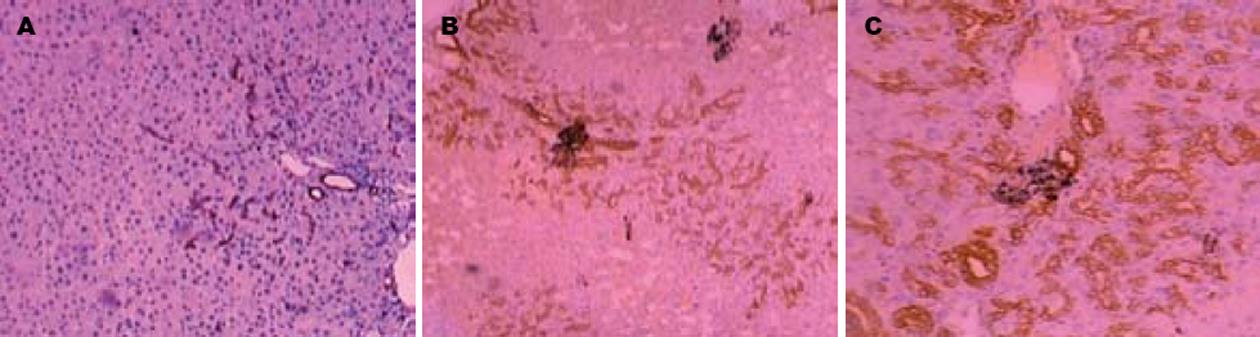

依据OV-6阳性染色和细胞形态学计数HOC. 对照组未见HOC. 模型组、PB组在肝切后4 h无明显HOC增生, 模型组4-16 d各时点HOC数量分别为: 8.20±1.50, 26.53±1.56, 16.60±2.30, 11.10±3.20个, HOC增殖呈逐渐升高至8 d达峰值后下调趋势. PB组4-16 d各时点HOC数量分别为: 14.20±3.57, 38.24±5.20, 28.65±4.87, 18.58±3.54个, 与模型组比较HOC增殖趋势相似, 但增殖水平高、持续时间长(图2).

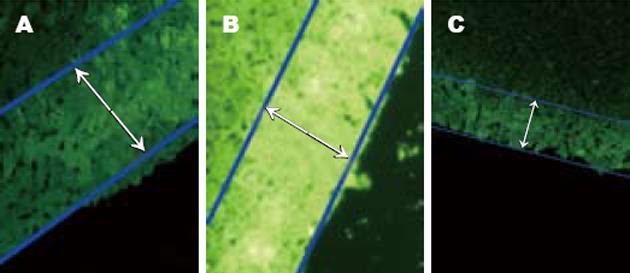

IL/DT检测结果显示对照组GJIC功能良好, 染料扩散距离大约250.0±5.0 μm, 约相当于10个肝细胞的直径. 模型组4 h-16 d各时点染料扩散距离低于对照组(P<0.01), 分别为: 84.5±3.4, 60.6±3.3, 108.6±4.2, 150.6±2.6, 199.6±3.7 μm, 在4 h明显降低、4 d至低峰、8 d后逐渐恢复. PB组4 h-16 d各时点染料扩散距离与模型组规律相同, 但低于模型组(P<0.01), 分别为: 74.3±3.4, 38.4±2.9, 88.5±4.3, 126.7±4.5, 175.9±4.8 μm(图3).

免疫组化显示CX32表达于肝细胞膜上, 对照组每个肝细胞CX32阳性染色信号数为9.8±1.3个; 模型组、PB组各时点CX32的表达低于对照组(P<0.05), 模型组4 h-16 d各时点分别为: 5.10±0.70, 2.85±0.39, 3.19±0.20, 4.34±0.80, 7.20±0.68个, 在4 h表达下调, 4 d至低峰, 8 d后逐渐恢复. 与模型组比较PB组在4 h, 12, 16 d时点CX32表达减少(P<0.05), 在4, 8 d时点CX32表达增多(P<0.05), 4 h-16 d各时点分别为: 3.96±0.28, 3.56±0.20, 3.68±0.20, 4.10±0.48, 6.21±0.42个(图4).

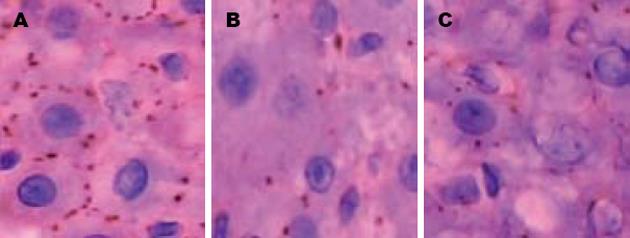

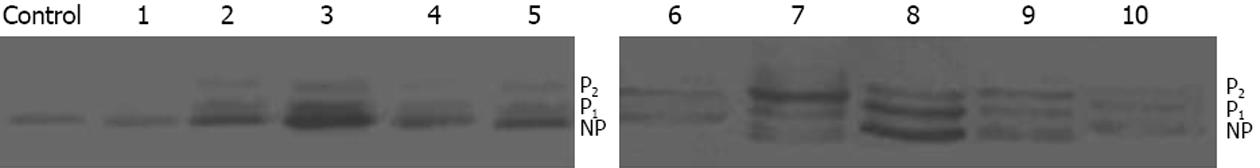

免疫组化显示CX43表达于汇管区, 伴随HOC数量增加而染色增强. Western blot结果显示对照组大鼠肝组织CX43蛋白水平很低, 模型组、PB组CX43蛋白表达在4 h上调、4 d表达明显、8 d达高峰、12 d后下降, 呈逐渐升高而后逐渐恢复趋势, 模型组4 h-16 d各时点分别为对照组的: 1.14±0.17, 3.87±0.35, 5.28±0.48, 2.96±0.33, 2.12±0.19倍, 与对照组比较4 h CX43蛋白的表达上调, 无显著差异(P>0.05), 余时间点明显高于对照组(P<0.01). PB组各时点CX43蛋白表达上调分别为对照组的: 1.32±0.24, 2.18±0.20, 2.97±0.22, 2.57±0.26, 1.67±0.27倍, 与模型组比较4 h上调, 无显著差异(P>0.05), 4-16 d表达明显减少(P<0.05). 模型组、PB组各时点CX43蛋白印迹呈现程度不同的三条带, 代表了CX43的不同磷酸化状态(P1, P2是磷酸化CX43, NP为非磷酸化CX43, 图5)[14].

模型组4 h-16 d各时点CX32 mRNA水平分别为对照组的0.82±0.13, 0.33±0.11, 0.51±0.13, 0.68±0.14, 1.12±0.18倍, 在4 h开始下降, 4 d达低峰, 8 d后逐渐恢复, 4 h, 4, 8, 12 d时点明显低于对照组(P<0.01), 16 d时点与对照组比较上调(P>0.05). PB组4 h-16 d各时点CX32 mRNA分别为对照组的: 0.65±0.14, 0.46±0.12, 0.66±0.16, 0.76±0.15, 1.42±0.13倍, 与模型组比较4 h时点无显著差异(P>0.05), 4-16 d时点明显升高(P<0.05, 图6).

对照组CX43 mRNA表达很低. 模型组4 h-16 d各时点CX43 mRNA分别为对照组的1.09±0.16, 2.82±0.23, 5.46±0.58, 3.34±0.64, 0.91±0.11倍, 即在建模后4 h上调(P>0.05), 4 d表达明显升高, 12 d达高峰, 4, 8, 12 d时点明显高于对照组(P<0.01), 16 d低于对照组, 但无显著差异(P>0.05). PB组4 h-16 d各时点CX43 mRNA分别为对照组的: 1.48±0.14, 4.34±0.43, 6.69±0.74, 5.83±0.57, 2.74±0.39倍, 与模型组比较各时点CX43 mRNA表达上调(P<0.05), 表现为峰值高, 持续时间长(图6).

细胞作为一个开放的体系, 时刻通过细胞膜与周围的环境发生着物质、能量和信息的交换, 从而调节细胞正常的生长、增殖、分化过程[6,15-16]. 目前越来越多的证据显示[17-21], CX介导的GJIC作为细胞间唯一、直接的信息交流形式可调节多种非肝源干细胞的增殖、分化过程. 但是肝脏GJIC对体内HOC的调控目前尚未见文献报道.

HOC是肝干细胞的子代细胞, 大鼠Solt-Farber(2-AAF/PH)模型是研究HOC应用最多的动物模型之一[22]. 本实验中, 对照组大鼠肝组织结构完整, 未见增生反应及HOC, 且GJIC功能良好; 模型组大鼠肝索结构紊乱, 肝细胞水肿、变性坏死, 4 d可见HOC增殖, 8 d增殖达到高峰, 12 d后数量逐渐减少. IL/DT结果显示肝脏GJIC 4 h明显降低, 4 d至低峰, 8 d后逐渐恢复. GJIC功能与HOC的增殖趋势相反, 且变化时点早于HOC的增殖. 结果表明肝脏GJIC的功能与HOC的增殖密切关联; PB是肝脏GJIC的抑制剂[9,23-26], 可进一步下调各时点2-AAF/PH大鼠肝脏的GJIC, 明显增加4-16 d各时点的HOC数量. 结果提示肝脏GJIC的抑制能促进2-AAF/PH大鼠体内HOC增殖.

肝细胞表达CX32, 而HOC表达CX43, 是肝脏GJIC的功能基础. 为了明确模型组、PB组大鼠肝脏GJIC功能抑制的机制, 免疫组化结果显示模型组、PB组大鼠肝脏CX32蛋白的表达与GJIC趋势相同, Western blot结果显示CX43蛋白的表达与GJIC趋势相反. 表明GJIC下调是CX32表达抑制所致(与CX的细胞特异性表达相关[27]). 与模型组比较PB组在4, 8 d时点CX32表达增多(P<0.05, 与高增殖的HOC分化成较多的肝细胞相关), 而肝脏GJIC各时点均低于模型组, 说明PB可能也在CX32的通道门控上抑制大鼠2-AAF/PH肝脏的GJIC; 同步进行的CX32 mRNA检测显示, 模型组、PB组肝脏CX32蛋白与mRNA表达均呈下调趋势, 说明CX32的蛋白下调是由CX32 mRNA转录减少所致; 与模型组比较PB组CX32 mRNA在4 h表达减少(P<0.05), 4-16 d增加(P<0.05, 而CX32蛋白表达在4 h, 12, 16 d时点低于模型组, 说明PB能在翻译或翻译后调节大鼠2-AAF/PH肝脏CX32蛋白的表达(机制待明). 模型组、PB组肝脏CX43蛋白和mRNA各时点均呈上调趋势, 说明CX43蛋白的上调是由mRNA转录增加引起的; 与模型组比较, PB组CX43 mRNA 4 h-16 d升高, 而CX43蛋白4-16 d下降, 这种蛋白与mRNA表达的分离现象说明了PB可能在翻译或翻译后抑制2-AAF/PH肝脏的CX43蛋白表达. 抑制GJIC可减少细胞凋亡、分化和生长抑制, 增加细胞增殖[15]. PB组HOC增殖数较模型组多, 而CX43蛋白表达减少, 说明PB不仅能降低肝细胞与偶联细胞的GJIC, 而且通过抑制HOC的CX43蛋白表达, 减少HOC与偶联细胞的GJIC, 解除HOC生长抑制, 促进HOC的增殖.

CX形成GJ的通讯能力不仅是被动的物质转运, 而且对交流物质有高选择性. 例如, 利用离子替代实验发现不同的CX通道对阴阳离子渗透能力差别高达10倍以上[28], 不同的CX对ATP、IP3、腺苷、谷光甘肽选择转运能力差别在10-100倍[29-31]. CX43, CX32构成的GJ对谷氨酸盐和谷光甘肽转运效率相似, 而CX43对核苷(特别是ADP, ATP)转运比CX32通道快10倍, 二者对核苷转运可产生2-3倍的差异. 因此, 通过调节大鼠2-AAF/PH肝脏CX32及CX43时空表达模式, 改变肝脏对生长信息的整合, 是PB促进体内HOC增殖的关键因素.

总之, 改变大鼠2-AAF/PH模型肝脏CX32, CX43的时空表达模式, 降低肝细胞及HOC与其偶联细胞的GJIC, 可解除HOC生长抑制, 促进HOC的增殖. 因此, 通过基因转染或药物诱导, 改变HOC或其偶联细胞的GJIC功能, 可调节HOC的增殖、分化过程. GJIC可能是体外修饰HOC实现其定向增殖、分化的一个关键靶点..

缝隙连接蛋白几乎表达于各种组织细胞, 介导的缝隙连接细胞间通讯(GJIC)是其参与调节生物学过程的核心. GJIC可调节多种干细胞细胞的生长、增殖及分化过程, 但是对肝卵圆细胞(肝干细胞的子代细胞)的作用目前所知尚少. 本实验通过抑制肝脏GJIC功能, 构建肝卵圆细胞增殖模型, 从CX32、CX43表达角度探讨肝脏GJIC对体内肝卵圆细胞的调控.

肝卵圆细胞可分化为肝细胞(表达CX32)及胆管上皮细胞(表达CX43), 因而探讨CX32和CX43对肝卵圆细胞分化的影响, 可能是阐明肝干细胞分化调控机制的关键.

CX及介导的GJIC可为体外修饰肝卵圆细胞实现其定向增殖、分化提供一个关键靶点.

缝隙连接细胞间通讯的选择渗透特性: 缝隙连接细胞间通讯(GJIC)是目前证实相邻细胞间唯一、直接的物质信息交流形势. 允许小分子物质(分子量<1000 Da)在细胞间交换, 从而发挥其生物学效应. 大量实验表明CX形成GJ的通讯能力不仅是被动的物质转运, 而且对交流物质有高选择性. 例如, 利用离子替代实验发现不同的CX通道对阴阳离子渗透能力差别高达10倍以上, 对ATP、IP3、腺苷、谷光甘肽选择转运能力差别在10-100倍. CX的通道选择渗透特性是其参与调节复杂生物学过程的基础.

本文探讨了肝脏GJIC对体内肝卵圆细胞增殖的影响, 文章设计合理, 方法先进, 得出了有意义的结论, 有一定创新性和学术价值.

编辑: 张焕兰 电编:张敏

| 1. | Watt FM, Hogan BL. Out of Eden: stem cells and their niches. Science. 2000;287:1427-1430. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Spradling A, Drummond-Barbosa D, Kai T. Stem cells find their niche. Nature. 2001;414:98-104. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Nguyen LN, Furuya MH, Wolfraim LA, Nguyen AP, Holdren MS, Campbell JS, Knight B, Yeoh GC, Fausto N, Parks WT. Transforming growth factor-beta differentially regulates oval cell and hepatocyte proliferation. Hepatology. 2007;45:31-41. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Knight B, Akhurst B, Matthews VB, Ruddell RG, Ramm GA, Abraham LJ, Olynyk JK, Yeoh GC. Attenuated liver progenitor (oval) cell and fibrogenic responses to the choline deficient, ethionine supplemented diet in the BALB/c inbred strain of mice. J Hepatol. 2007;46:134-141. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Lim R, Knight B, Patel K, McHutchison JG, Yeoh GC, Olynyk JK. Antiproliferative effects of interferon alpha on hepatic progenitor cells in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology. 2006;43:1074-1083. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Trosko JE, Madhukar BV, Chang CC. Endogenous and exogenous modulation of gap junctional intercellular communication: toxicological and pharmacological implications. Life Sci. 1993;53:1-19. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Yanagiya T, Tanabe A, Hotta K. Gap-junctional communication is required for mitotic clonal expansion during adipogenesis. Obesity (. Silver Spring). 2007;15:572-582. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Lu F, Gao J, Ogawa R, Hyakusoku H. Variations in gap junctional intercellular communication and connexin expression in fibroblasts derived from keloid and hypertrophic scars. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119:844-851. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Kolaja KL, Engelken DT, Klaassen CD. Inhibition of gap-junctional-intercellular communication in intact rat liver by nongenotoxic hepatocarcinogens. Toxicology. 2000;146:15-22. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Sai K, Kanno J, Hasegawa R, Trosko JE, Inoue T. Prevention of the down-regulation of gap junctional intercellular communication by green tea in the liver of mice fed pentachlorophenol. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1671-1676. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Jeong SH, Habeebu SS, Klaassen CD. Cadmium decreases gap junctional intercellular communica-tion in mouse liver. Toxicol Sci. 2000;57:156-166. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Dagli ML, Yamasaki H, Krutovskikh V, Omori Y. Delayed liver regeneration and increased suscepti-bility to chemical hepatocarcinogenesis in trans-genic mice expressing a dominant-negative mutant of connexin32 only in the liver. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:483-492. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Asamoto M, Hokaiwado N, Murasaki T, Shirai T. Connexin 32 dominant-negative mutant transgenic rats are resistant to hepatic damage by chemicals. Hepatology. 2004;40:205-210. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Musil LS, Goodenough DA. Biochemical analysis of connexin43 intracellular transport, phosphorylation, and assembly into gap junctional plaques. J Cell Biol. 1991;115:1357-1374. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Trosko JE, Ruch RJ. Cell-cell communication in carcinogenesis. Front Biosci. 1998;3:d208-236. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Nicholson BJ. Gap junctions - from cell to molecule. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4479-4481. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | van Herwaarden AE, Schinkel AH. The function of breast cancer resistance protein in epithelial barriers, stem cells and milk secretion of drugs and xenotoxins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:10-16. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Trosko JE, Chang CC, Wilson MR, Upham B, Hayashi T, Wade M. Gap junctions and the regulation of cellular functions of stem cells during development and differentiation. Methods. 2000;20:245-264. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Trosko JE, Chang CC, Upham BL, Tai MH. Ignored hallmarks of carcinogenesis: stem cells and cell-cell communication. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1028:192-201. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Yang SR, Cho SD, Ahn NS, Jung JW, Park JS, Jo EH, Hwang JW, Jung JY, Kim TY, Yoon BS. Role of gap junctional intercellular communication (GJIC) through p38 and ERK1/2 pathway in the differentiation of rat neuronal stem cells. J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67:291-294. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Trosko JE. From adult stem cells to cancer stem cells: Oct-4 Gene, cell-cell communication, and hormones during tumor promotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1089:36-58. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Paku S, Nagy P, Kopper L, Thorgeirsson SS. 2-acetylaminofluorene dose-dependent differentia-tion of rat oval cells into hepatocytes: confocal and electron microscopic studies. Hepatology. 2004;39:1353-1361. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Ito S, Tsuda M, Yoshitake A, Yanai T, Masegi T. Effect of phenobarbital on hepatic gap junctional intercellular communication in rats. Toxicol Pathol. 1998;26:253-259. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Ren P, Mehta PP, Ruch RJ. Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication by tumor promoters in connexin43 and connexin32-expressing liver cells: cell specificity and role of protein kinase C. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19:169-175. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Ren P, Ruch RJ. Inhibition of gap junctional intercellular communication by barbiturates in long-term primary cultured rat hepatocytes is correlated with liver tumour promoting activity. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:2119-2124. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Jansen LA, Jongen WM. The use of initiated cells as a test system for the detection of inhibitors of gap junctional intercellular communication. Carcinogenesis. 1996;17:333-339. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Harris AL. Emerging issues of connexin channels: biophysics fills the gap. Q Rev Biophys. 2001;34:325-472. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | Bevans CG, Kordel M, Rhee SK, Harris AL. Isoform composition of connexin channels determines selectivity among second messengers and uncharg-ed molecules. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:2808-2816. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | Goldberg GS, Lampe PD, Nicholson BJ. Selective transfer of endogenous metabolites through gap junctions composed of different connexins. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:457-459. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Nicholson BJ, Weber PA, Cao F, Chang H, Lampe P, Goldberg G. The molecular basis of selective permeability of connexins is complex and includes both size and charge. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2000;33:369-378. [PubMed] [DOI] |