修回日期: 2006-04-12

接受日期: 2006-04-20

在线出版日期: 2006-07-18

目的: 探讨饥饿后大鼠肠黏膜形态学结构的变化规律, 并动态观察GLN肠内补充对饥饿大鼠内毒素移位和肠黏膜免疫功能的影响.

方法: 采用饥饿大鼠模型, 将90只3月龄♂SD大鼠随机分为正常对照组N: (给予正常饮食n = 10)、饥饿组A (n = 40)、谷氨酰胺组B (n = 40) 3个大组, 分别于饥饿后3, 5, 7, 9 d, 取门静脉血测血浆内毒素的变化, 在光镜下观察肠组织的组织形态学改变, 利用免疫组化技术检测肠黏膜组织中SIgA的表达和CD4+、CD8+ T细胞的数量.

结果: A组大鼠饥饿后, 3 d可见小肠黏膜明显萎缩, 绒毛变短、变稀. 部分黏膜上皮细胞变性、坏死、脱落, 绒毛横径增宽, 高度缩短; 至饥饿后9 d上述变化更加明显. B组在饥饿后3 d较同时间点A组肠黏膜损伤有明显的改善, 小肠的黏膜厚度、绒毛数量、高度增加, 至饥饿后5 d基本恢复至N组水平. 随着饥饿时间的延长小肠黏膜再次出现黏膜萎缩、绒毛变短、变稀, 黏膜上皮细胞变性、坏死、脱落, 但明显轻于同时间点的A组. 饥饿后各时间点血浆内毒素与N组相比明显升高, A, B组均在饥饿后7 d达到高峰, B组在饥饿后3, 5, 7, 9 d较A组降低且有非常显著性差异(322.4±65.1, 389.4±32.6, 464.4±76.6, 413.7±67.2 EU/L vs527.1±74.9, 546.3±65.7, 623.9±85.9, 587.5±140.8 EU/L, 均P<0.01). 与N组比较, A组大鼠肠黏膜SIgA及CD4+, CD8+ T细胞数量明显减少, 差异有显著性(P<0.05, P<0.01). 补充GLN后, SIgA及CD4+, CD8+ T细胞数量明显升高, B组与A组比较差异非常显著(P<0.01).

结论: 大鼠饥饿后早期确有肠黏膜组织结构受损, 发生内毒素移位, 同时伴有肠黏膜免疫学屏障受损. 早期给予GLN可减轻肠黏膜的受损, 明显降低内毒素移位, 增强肠黏膜的免疫功能发挥肠黏膜的保护作用.

引文著录: 张小平, 程爱国, 陈玉红. 谷氨酰胺对饥饿大鼠内毒素移位和肠黏膜免疫功能的影响. 世界华人消化杂志 2006; 14(20): 1982-1986

Revised: April 12, 2006

Accepted: April 20, 2006

Published online: July 18, 2006

AIM: To investigate the changes in intestinal structure and function as well as the effect of enteral glutamine (GLN) supplement on the endotoxin translocation and immunological function in starved rats.

METHODS: Ninety male Sprague Dawley rats were randomly divided into 3 groups: normal control group (n = 10), starved group (group A, n = 40) and GLN group (group B, n = 40). The rats were sacrificed 3, 5, 7 and 9 d after starvation, respectively. Blood samples were collected from portal vein for the detection of plasma endotoxin and tissue samples removed from ileocecum were observed under light microscope for morphological changes. A contrasting study on the expression of secretary immunoglobulin A (sIgA) and the numbers of CD4+, CD8+ T lymphocytes were also performed between control group and other groups by immunohistochemical staining method.

RESULTS: The atrophy of intestinal mucosa and villa were observed 3 d after starvation in group A, with the degeneration, necrosis, and shedding of partial mucosal epithelial cells. The changes were gradually deteriorated till the 9th day after starvation. Those pathological changes were lighter in group B than those in group A on the 3rd day after starvation and restored to normal on the 5th day. As the starvation time prolonged, the atrophy, degeneration and necrosis of the mucosal epithelial cells appeared again in group B, but were still lighter than those in group A. The levels of endotoxin were significantly higher 3, 5, 7 and 9 d after starvation in both group A and B than those in the controls, and there were also marked differences between group B and A (322.4 ± 65.1, 389.4 ± 32.6, 464.4 ± 76.6, 413.7 ± 67.2 EU/L vs 527.1 ± 74.9, 546.3 ± 65.7, 623.9 ± 85.9, 587.5 ± 140.8 EU/L, all P < 0.01). The expression of sIgA and the numbers CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in intestinal mucosa were reduced significantly in group A and B, in compared with those in the controls (P < 0.05 or P < 0.01), and there were higher levels of sIgA and CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes in group B than those in group A (P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: The structure of intestinal mucosa is damaged in the earlier stage of starvation in rats, accompanied by endotoxin translocation and dysfunction of intestinal mucosal immune barrier. Early enteral nourishment of glutamine is helpful for inhibiting endotoxin translocation and improve immune function of intestinal mucosa.

- Citation: Zhang XP, Cheng AG, Chen YH. Effects of enteral glutamine supplement on endotoxin translocation and mucosal immune barrier in starved rats. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2006; 14(20): 1982-1986

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v14/i20/1982.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v14.i20.1982

饥饿时, 外界能源物质缺乏, 机体从依赖食物提供的能量逐步适应于靠自身储脂来提供能量. 谷氨酰胺(GLN)作为一种生理性无毒的氨运输载体, 是病理状况下人体不可缺少的必要氨基酸, 其缺乏会引起细胞能量的匮乏, 机体免疫力下降, 出现"肠黏膜饥饿", 明显降低存活率,但至今关于饥饿后肠屏障功能的研究及饥饿后GLN补充的研究仍很少. 我们测定门静脉血内毒素的变化, 观测肠组织的组织形态学改变以及肠黏膜组织中SIgA的表达和CD4+, CD8+ T细胞的数量, 探讨饥饿后大鼠肠黏膜形态学结构的变化规律, 动态观察GLN肠内补充对饥饿大鼠内毒素移位和肠黏膜免疫功能的影响, 探讨早期添加GLN对肠黏膜屏障的保护作用.

健康♂3月龄成年SD大鼠(由华北煤炭医学院动物实验中心提供)90只, 体质量250±20 g, 按体质量随机分成正常对照组N(n = 10)、饥饿组A(n = 40)、谷氨酰胺组B(n = 40), 单笼适应性喂养1 wk后用于实验. GLN颗粒由重庆药友制药有限公司提供.

实验期无饲料供应, 自由摄水, 直至被活杀. 补充组用GLN溶液灌胃补充, 每日1.0 g/kg. 饥饿开始当日上午处死对照组大鼠, 以后分别于饥饿3, 5, 7, 9 d上午同一时间在全饥饿组及补充组中随机取10只动物处死. 大鼠麻醉后固定于手术台上, 在无菌操作条件下剖开腹部, 用去热原空针抽取门静脉血2 mL装入60Co去热原的内毒素试管, 标本在4 ℃冰箱保存, 5000 r/min离心5 min, 分离血浆后立即将血浆置-20 ℃冰箱保存, 待测. 内毒素测定按内毒素鲎试剂测定法要求步骤操作. 距回盲部5 cm以上取2 cm回肠, 100 g/L多聚甲醛固定, 石蜡包埋、切片. 另取2 cm回肠迅速置于液氮中速冻, 然后取出组织冰块立即置入-80 ℃冰箱贮存备用. 冰冻切片冷丙酮固定10 min, 室温下干燥40 min, 3 mL/L H2O2阻断内源性过氧化物酶的活性10 min, 滴加试剂盒中推荐的复合消化液覆盖组织4 ℃孵育15-20 min, 非免疫马血清封闭非特异性背景10 min, 依次加入一抗(兔抗鼠抗体1:100, 室温下2 h), 二抗(生物素化山羊抗兔, 室温下30 min), 过氧化物酶室温下孵育30 min, 以上各步间均以PBS缓冲液洗3次, DAB显色, 苏木素复染, 上行梯度酒精脱水、透明、中性树胶封片, 分别计数10个高倍镜下阳性细胞数. 实验中以全饥饿组阳性片作为阳性对照, 用PBS代替一抗作为阴性对照.

统计学处理 计量资料数据以mean±SD表示, 采用SPSS统计软件包行t检验. 以P<0.05表示有显著意义.

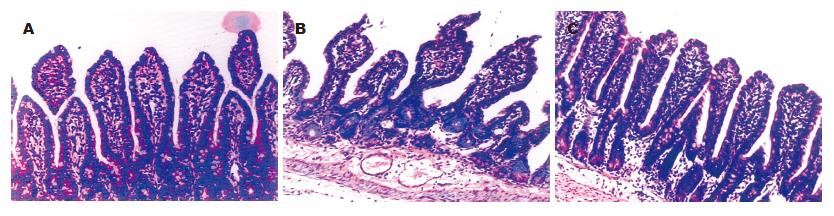

对照组正常小肠黏膜绒毛呈指状突起, 偶尔极少呈针状, 绒毛较长, 其高度是陷窝的数倍, 中间有一细的中央基质,有散在少量圆形细胞浸润, 表面覆以柱状上皮细胞, 其肠腔面可见浓集的刷状缘(图1A); 饥饿组回肠黏膜萎缩, 部分上皮细胞脱落,绒毛排列紊乱、稀疏(图1B); GLN谷氨酰胺组回肠黏膜较饥饿组增厚, 未见明显上皮细胞脱落, 绒毛排列整齐、致密(图1C).

门静脉血内毒素饥饿组和GLN组明显高于正常对照组(P<0.01). 同一时间点内门静脉血内毒素比较, GLN明显低于饥饿组(P<0.01, 表1).

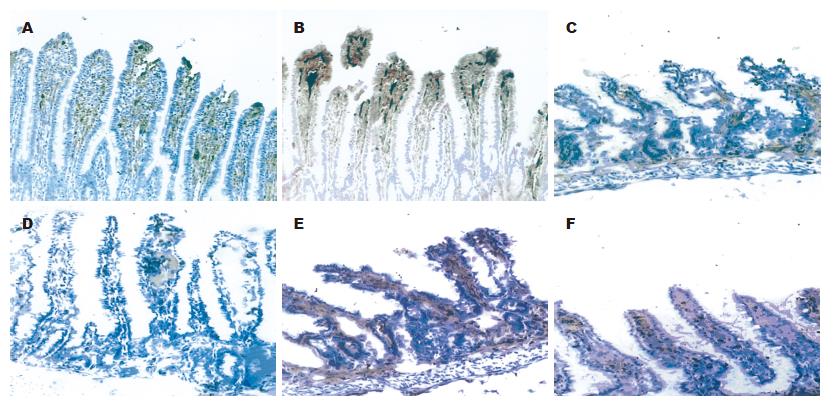

每组检测5例, 每例任选10个高倍视野, 分别计数10个高倍镜下阳性细胞数(cell/hp, mean±SD, ×400). 再行组内汇总进行统计分析(表2, 图2).

肠道作为在创伤后病情发生和转归中的重要作用已受到高度重视[1-4], 而肠道结构的维护是保护功能的基础. 饥饿后会导致机体产生严重的应激反应, 出现复杂的神经-内分泌系统介导的适应性变化, 结果出现选择性内脏血管痉挛以保持心脑等重要脏器的血液供应, 从而导致肠黏膜缺血、缺氧[5-6], 而且应激反应过程中, 肠黏膜因其特殊的动静脉血管对流系统和血管的解剖特点, 使他更容易受到应激的损害[7]. GLN是一种非必需氨基酸, 他是由谷氨酰胺合成酶(GS)将谷氨酸和谷氨酸盐合成而成的. GS在胃内活性最高, 占整个胃肠道的90%, 其mRNA在胃肠道高表达. 谷氨酰胺酶活性在小肠内最高, 说明小肠是GLN最重要的代谢器官, 但其本身既不合成也不能储存GLN, 必须依赖其他脏器合成或外源性GLN[8-10]. GLN不仅是肠道黏膜细胞代谢活动的主要能源, 更是维持肠道黏膜结构完整性不可缺少的特殊氨基酸[11]. 有报道显示预防性应用谷氨酰胺可减轻由于创伤和内毒素血症引起的肠道渗透性增加和细菌移位[12]. 本实验结果表明, 补充GLN的大鼠在饥饿后回肠黏膜厚度、绒毛高度和陷窝深度明显增高, 且绒毛排列整齐、致密, 和饥饿组相比, 更接近正常肠道结构, 维护肠道功能.

近年研究显示, 严重创伤后中性粒细胞、炎症介质、细胞因子及缺血再灌注损伤可介导肠黏膜结构受损, 肠道屏障功能下降, 肠道内微生态环境和正常菌群失调, 引起肠道内细菌和内毒素向邻近组织和肠外组织移位, 导致肠源性菌血症和内毒素血症甚至脓血症[12-14]. GLN不仅是快速生长和分化的肠黏膜上皮细胞的重要氧化燃料和能量合成底物[15], 也是维护肠黏膜结构、黏膜屏障功能、肠道免疫功能和微生态环境的重要调节因子. 大量资料表明[16-19], GLN营养支持在肠黏膜屏障功能、改善肠道内微环境和预防肠源性细菌和内毒素移位中起着非常重要的作用. 实验结果显示, 饥饿后, 饥饿组门静脉血中内毒素含量明显高于GLN组, 提示饥饿后即有肠源性细菌移位的发生和内毒素进入门静脉. 与饥饿组相比, 给予GLN后可使血浆内毒素水平明显下降, 证实饥饿后GLN可保护肠黏膜屏障, 从而减少饥饿后细菌/内毒素移位, 提示GLN在减轻饥饿后肠黏膜损伤, 维护肠道正常菌群、减少肠源性菌血症、内毒素血症, 甚至脓血症发生中起积极的作用.

据报道, 全肠道外营养(TPN)可致肠道谷氨酰胺来源减少, 上皮细胞和淋巴细胞增殖代谢受损, 导致IL-2等促B细胞分化因子减少, 使产IgA浆细胞池减少, 合成分泌SIgA减少, 肠腔细菌SIgA包被率下降[19-20]. SIgA的减少导致肠黏膜抗细菌黏附、定植能力减弱, 细菌和毒素大量移位至肠外器官, 刺激各类炎症因子的大量释放, 产生全身性炎症反应, 从而引起细菌和毒素的再次大量入侵, 构成"二次打击", 使SIgA的产生进一步的减少, 引发多器官功能障碍[21-22]. 谷氨酰胺具有肠道免疫功能刺激作用[23], 并能促进中性粒细胞和单核细胞的产生与功能, 延迟其自然凋亡过程[24-25]. 谷氨酰胺作为肠内营养的补充, 可有效地维持严重烧伤患者的细胞免疫功能[26], 提高肠源性菌血症大鼠的肠黏膜细胞和体液免疫功能[27-28]. 本实验结果提示: 谷氨酰胺促进SIgA的合成和分泌, 从免疫屏障的第一环节减少细菌的黏附, 防止肠黏膜受到再次打击.

饥饿可导致肠黏膜局部CD4+、CD8+ T淋巴细胞明显下降, 细胞因子的产生减少, 免疫调节功能减弱, 肠黏膜局部免疫功能减退.

谷氨酰胺可提高肠黏膜局部淋巴细胞的数量及功能维持, 调节特异性SIgA的产生与分泌, 从两方面保护肠黏膜的屏障功能, 降低肠源性细菌移位.

随着我国矿难事故的日趋增加, 研究被困井下矿工全饥饿状态下人的生命极限有多长, 机体的代谢及全身脏器有何影响, 能否有一种药物可以达到使被埋困的工人尽可能地延长生命、保持各脏器功能于生理状态、赢得解救时间的目的, 具有重要的意义. 其中, 由于在应激反应中, 肠道的变化出现最早, 恢复最晚, 故Wilmore称肠道为应激的中心器官.

本文首先对全饥饿状态下大鼠内毒素移位和肠黏膜免疫功能的改变以及谷氨酰胺的干预作用进行了实验研究, 这在国内外尚未见报道.

此项研究将继续深入, 最终以期找到一种便携式全饥饿状态下保护脏器功能和延长生命的药物.

本文从饥饿后大鼠肠黏膜形态学结构的变化规律, 动态观察谷氨酰胺肠内补充对饥饿大鼠内毒素移位和肠黏膜免疫功能的影响, 探讨了早期添加谷氨酰胺对肠黏膜屏障的保护作用, 文章设计合理, 研究方法经典, 结论基本可靠.

电编: 张敏 编辑:潘伯荣

| 1. | Chang JX, Chen S, Ma LP, Jiang LY, Chen JW, Chang RM, Wen LQ, Wu W, Jiang ZP, Huang ZT. Functional and morphological changes of the gut barrier during the restitution process after hemorrhagic shock. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:5485-5491. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Wei YJ, Wang RL, Li GP. Influence on the concentration of plasma endotoxin by inhibition of complement activation in traumatic hemorrhagic shock rats. Zhongguo Weizhongbingjijiu Yixue. 2006;18:180-183. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Davidson MT, Deitch EA, Lu Q, Hasko G, Abungu B, Nemeth ZH, Zaets SB, Gaspers LD, Thomas AP, Xu DZ. Trauma-hemorrhagic shock mesenteric lymph induces endothelial apoptosis that involves both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent mechanisms. Ann Surg. 2004;240:123-131. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Oztuna V, Ersoz G, Ayan I, Eskandari MM, Colak M, Polat A. Early internal fracture fixation prevents bacterial translocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;446:253-258. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Ueno C, Fukatsu K, Maeshima Y, Moriya T, Shinto E, Hara E, Nagayoshi H, Hiraide H, Mochizuki H. Dietary restriction compromises resistance to gut ischemia-reperfusion, despite reduction in circulating leukocyte activation. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2005;29:345-351. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Kong SE, Hall JC, Cooper D, McCauley RD. Starvation alters the activity and mRNA level of glutaminase and glutamine synthetase in the rat intestine. J Nutr Biochem. 2000;11:393-400. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Swank GM, Deitch EA. Role of the gut in multiple organ failure: bacterial translocation and permeabi-lity changes. World J Surg. 1996;20:411-417. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Papaconstantinou HT, Chung DH, Zhang W, Ansari NH, Hellmich MR, Townsend CM Jr, Ko TC. Prevention of mucosal atrophy: role of glutamine and caspases in apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000;4:416-423. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | DeMarco VG, Li N, Thomas J, West CM, Neu J. Glutamine and barrier function in cultured Caco-2 epithelial cell monolayers. J Nutr. 2003;133:2176-2179. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wischmeyer PE. Clinical applications of L-glutamine: past, present, and future. Nutr Clin Pract. 2003;18:377-385. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | White JS, Hoper M, Parks RW, Clements WD, Diamond T. Glutamine improves intestinal barrier function in experimental biliary obstruction. Eur Surg Res. 2005;37:342-347. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Ding LA, Li JS. Effects of glutamine on intestinal permeability and bacterial translocation in TPN-rats with endotoxemia. World J Gastroenterol. 2003;9:1327-1332. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Caruso JM, Feketeova E, Dayal SD, Hauser CJ, Deitch EA. Factors in intestinal lymph after shock increase neutrophil adhesion molecule expression and pulmonary leukosequestration. J Trauma. 2003;55:727-733. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Mbachu EM, Klein LV, Rubin BB, Lindsay TF. A monoclonal antibody against cytokine-induced neutrophil chemoattractant attenuates injury in the small intestine in a model of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39:1104-1111. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Gosain A, Gamelli RL. Role of the gastrointestinal tract in burn sepsis. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2005;26:85-91. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Yang H, Soderholm J, Larsson J, Permert J, Olaison G, Lindgren J, Wiren M. Glutamine effects on permeability and ATP content of jejunal mucosa in starved rats. Clin Nutr. 1999;18:301-306. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Panigrahi P, Gewolb IH, Bamford P, Horvath K. Role of glutamine in bacterial transcytosis and epithelial cell injury. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1997;21:75-80. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | De-Souza DA, Greene LJ. Intestinal permeability and systemic infections in critically ill patients: effect of glutamine. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1125-1135. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | Wu GH, Wang H, Zhang YW, Wu ZH, Wu ZG. Glutamine supplemented parenteral nutrition prevents intestinal ischemia- reperfusion injury in rats. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10:2592-2594. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Ali S, Roberts PR. Nutrients with immune-modulating effects: what role should they play in the intensive care unit? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006;19:132-139. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 21. | Cunningham-Rundles S, Lin DH. Nutrition and the immune system of the gut. Nutrition. 1998;14:573-579. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Renegar KB, Kudsk KA, Dewitt RC, Wu Y, King BK. Impairment of mucosal immunity by parenteral nutrition: depressed nasotracheal influenza-specific secretory IgA levels and transport in parenterally fed mice. Ann Surg. 2001;233:134-138. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Kudsk KA. Effect of route and type of nutrition on intestine-derived inflammatory responses. Am J Surg. 2003;185:16-21. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Gismondo MR, Drago L, Fassina MC, Vaghi I, Abbiati R, Grossi E. Immunostimulating effect of oral glutamine. Dig Dis Sci. 1998;43:1752-1754. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Furukawa S, Saito H, Inoue T, Matsuda T, Fukatsu K, Han I, Ikeda S, Hidemura A. Supplemental glutamine augments phagocytosis and reactive oxygen intermediate production by neutrophils and monocytes from postoperative patients in vitro. Nutrition. 2000;16:323-329. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Pithon-Curi TC, Schumacher RI, Freitas JJ, Lagranha C, Newsholme P, Palanch AC, Doi SQ, Curi R. Glutamine delays spontaneous apoptosis in neutrophils. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;284:C1355-C1361. [PubMed] [DOI] |