修回日期: 2005-09-13

接受日期: 2005-09-30

在线出版日期: 2006-01-08

目的: 研究食管癌细胞的分化状态对ALA产生的内源性光敏剂PpIX累积水平的影响, 及对PDT的应答敏感程度.

方法: 以高分化食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-450和低分化食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-70为研究对象, 利用荧光分光光度法测定不同浓度ALA处理后细胞内PpIX的浓度; 分别使用不同剂量的红光和蓝光对细胞进行照射处理, MTS法测定PDT对细胞的光毒毒性; TdT-流式细胞法测定PDT诱导的凋亡水平, 并观察凋亡细胞的胞核形态.

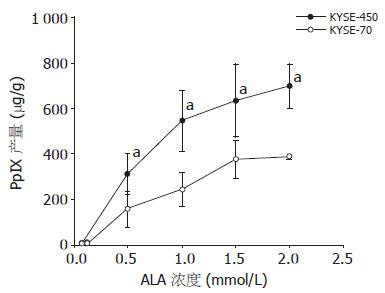

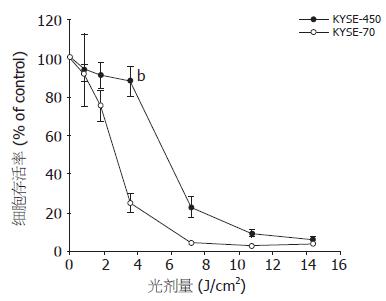

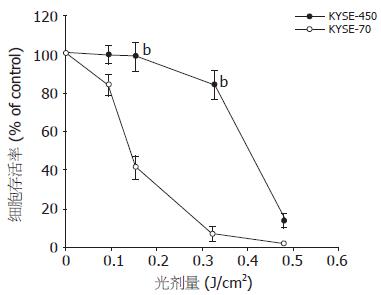

结果: 高分化KYSE-450细胞比低分化KYSE-70细胞具有更强的PpIX合成或累积水平, 两者PpIX绝对浓度值在高于0.5 mmol/L ALA时差异显著(315.2±88.3 vs 156.9±79.2, P<0.05); 虽然高分化细胞PpIX产量高于低分化细胞, 但无论是红光PDT还是蓝光PDT, 其敏感性均明显差于低分化细胞, 光剂量为3.6 J/cm2(红光)和0.16 J/cm2(蓝光)时, 两者细胞存活率有极显著差异(88.0±7.4 vs 25.2±4.9, 红光; 97.4±7.3 vs 40.8±4.2, 蓝光; P<0.01); KYSE-450凋亡率(12.5%)亦低于KYSE-70(23.2%), 细胞主要以坏死方式为主.

结论: 食管鳞癌细胞的分化影响了内源性光敏剂PpIX的细胞内水平; PDT效应并不单纯依赖于细胞内的光敏剂含量, 细胞的生物学特征如分化状态也影响了PDT的效果; 高分化细胞部分通过抑制凋亡抵制了PDT作用.

引文著录: 汲振余, 赵立群, 杨观瑞, 薛乐勋, 索振河, JahnM.Nesland, 彭迁. 食管鳞癌细胞分化状态对内源性光敏剂 PpIX 产量的影响及对 PDT 的应答. 世界华人消化杂志 2006; 14(1): 6-11

Revised: September 13, 2005

Accepted: September 30, 2005

Published online: January 8, 2006

AIM: To explore the effects of differentiation on 5-aminolevulinic acid (5-ALA)-derived endogen-ous protopophyrin IX (PpIX) production and photodynamic therapy (PDT) in human esopha-geal cancer.

METHODS: Well differentiated KYSE-450 and poorly differentiated KYSE-70 cell lines were used in this study. Intracellular PpIX production after incubation with various concentrations of ALA was quantified with spectrofluorometry. Moreover, Cell survival after ALA-PDT with different light doses of red light (> 600 nm) and blue light (450 nm) was determined by MTS assay. The apoptosis of the cells after ALA-PDT were detected by flow cytometry with TdT staining as well as fluorescent microscopy with Hoechst 33342 staining.

RESULTS: KYSE-450 cells had a higher PpIX production than KYSE-70 did, and a significant difference was found when the ALA concentration was reached above 0.5 mmol/L (315.2 ± 88.3 vs 156.9 ± 79.2, P < 0.05). However, the sensitivity of the well-differentiated cells to ALA-PDT was lower than that of the poorly-differentiated ones. Cell viability assay showed a significant difference between KYSE-450 and KYSE-70 cells when the red light of 3.6 J/cm2 and blue light of 0.16 J/cm2 were employed (red light: 88.0 ± 7.4% vs 25.2 ± 4.9%, P < 0.01; blue light: 97.4% ± 7.3 vs 40.8 ± 4.2%, P < 0.01). The apoptotic rate of KYSE-450 cells (12.5%) was lower than that of KYSE-70 cells (23.2%), and necrosis was the main death style for both kinds of cells.

CONCLUSION: The differentiation of esophageal cancer cells can affect the synthesis and accumulation of ALA-induced endogenous PpIX. The efficacy of ALA-PDT don't just depended on the amount of intracellular PpIX, and the well-differentiated cells with more PpIX production are more resistant to ALA-PDT than the poorly-differentiated cells with less PpIX production.

- Citation: Ji ZY, Zhao LQ, Yang GR, Xue LX, Suo ZH, Nesland JM, Peng Q. Effects of differentiation of human esophageal cancer cells on 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced endogenous protopophyrin IX production and photodynamic therapy. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2006; 14(1): 6-11

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v14/i1/6.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v14.i1.6

光动力学疗法(photodynamic therapy, PDT)用于浅表肿瘤的治疗已20 a[1]. Photofrin, 5-氨基乙酰丙酸(5-ALA)和他的脂性衍生物(Metvix和Hexvix)及m-THPC(m-Tetra (hydroxyphenyl) chlorin, 商品名Foscan)已进入临床[2-6]. PDT应用可以选择性存积于肿瘤细胞内的光敏剂, 经一定波长的可见光激发后, 产生单态氧(1O2)和自由基等活性物质, 使生物大分子如蛋白质, 脂肪酸等产生不可逆氧化, 导致亚细胞结构与功能的损害, 引起细胞凋亡或坏死[7-10]. 虽然以ALA为光敏剂前体物的PDT(ALA-PDT)已经用于食管癌及癌前病变的治疗, 但其具体杀伤机制还不十分清楚, 而且许多因素能影响PDT的效果. 这些因素除了光敏剂, 所选用的光及氧分子以外, 还包括肿瘤细胞的生物学性状和细胞内某些促/抑凋亡基因的表达活性等[2,11]. 由于不同分化状态的肿瘤细胞内源性光敏剂原卟啉IX(protopophyrin IX, PpIX)的合成过程中的一些代谢酶活性可存在差异, 因而有可能影响到光敏剂在肿瘤细胞内的水平, 并可能导致对PDT的不同反应[12-14]. 我们应用高分化和低分化的食管鳞状细胞癌细胞系, 研究细胞内产生内源性光敏剂的效率及对PDT的应答水平, 以期为临床提供指导.

高分化食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-450和低分化食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-70由美国ATCC提供. 5-ALA和PpIX由PhotoCure ASA(挪威)提供. 荧光分光光度计为LS-5型(Perkin Elmer). PDT光辐射仪为PCI Biotech公司(挪威)生产. TdT酶为Roche公司生产, 链霉素-FITC荧光信号反应液为Amersham LifeScience产品. Bradford BCA蛋白质测定试剂盒购自Pierce公司. 流式细胞仪为BD FACSDiVa Option(BD Biosciences公司, 美国). 荧光显微镜为Nikon Eclips E800, 附带-60 ℃ 高分辨率CCD成像设备. MTS为Promega产品, RPMI 1640培养液及其他试剂均购自Sigma.

规 生长至80%左右融合的KYSE-450和KYSE-70细胞用胰蛋白酶-EDTA消化, 接种4×105个细胞至6孔培养板, 37 ℃ 50 mL/L CO2培养箱培养过夜, 使细胞充分贴壁. 次日用含不同浓度ALA的无血清RPMI 1640液孵育4 h, PBS洗2次后加入卟啉抽提溶液(1 mol/L高氯酸/甲醇, 1:1)1 mL, 37 ℃孵育30 min后收获细胞, 1 400 r/min离心5 min, 荧光分光光度计测定上清液荧光光密度值(激发波长405 nm, 发射波长603 nm), 并加入适量已知浓度的PpIX标准, 使荧光光密度值增大至原来的1-1.5倍, 按此校正值计算PpIX浓度. 以上操作须避光进行, 所有试验均设3个平行孔, 至少2次重复试验. 使用Bradford方法(BCA试剂盒)测定蛋白质浓度, 细胞除不加ALA外, 其他处理方法同上. 细胞收获后2 800 r/min离心10 min, 细胞沉淀用100 μL裂解液(含20 mmol/L Tris-HCl pH 7.2, 4 g/L SDS, 5 mmol/L EDTA, 5 mmol/L EGTA, 10 mmol/L焦磷酸盐)悬浮, 冰上30 min后超声处理25 s, 按试剂盒说明操作, 计算总蛋白量.

1.2.1 PDT处理及细胞存活率测定: KYSE-450和KYSE-70细胞按1.6×104个细胞/孔接种到96孔培养板, 次日用含1 mmol/L ALA的无血清RPMI 1640液孵育细胞4 h后, 立即PDT处理. 为与临床一致, 我们采用可见红光(波长600 nm以上)照射, 光剂量设定0.45, 0.9, 1.8, 3.6, 7.2, 14.4 J/cm2, 并设无光照射和无ALA空白对照. 处理完毕立即更换新鲜含100 mL/L小牛血清的培养液, 37 ℃ 50 mL/L CO2培养箱孵育24 h. 然后每孔加入MTS液20 μL, 37 ℃ 1 h, 测定490 nm处的吸光度值. 所有试验均设6个平行孔, 至少重复2次. 以无ALA但用相同光剂量处理的对照孔设置为100%, 其他试验孔以此为对照计算细胞存活率(%). 蓝光PDT处理方法同上, 使用光剂量为0.08, 0.16, 0.32, 0.48 J/cm2, 光波长为450 nm.

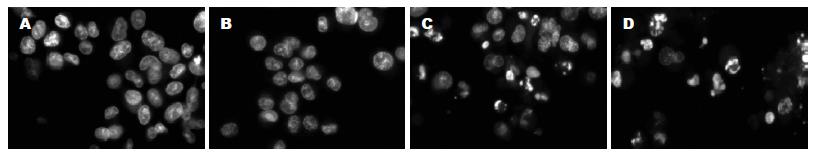

1.2.2 细胞凋亡的检测: TdT法测定细胞凋亡率. 接种4×105个细胞至6孔培养板, 1 mmol/L ALA处理4 h, 1.8 J/cm2光剂量PDT, 收获细胞, 纯甲醇固定, -20 ℃储存待测. 测前PBS洗涤, 离心, 细胞沉淀加入TdT反应液(含80 U TdT, 1.5 mmol/L CoCl2, 0.5 nmol/L Biotin-16-dUTP, 0.1 mmol/L DTT)50 μL, 37 ℃孵育30 min. PBS洗涤后, 冰上加入链霉素-FITC荧光信号反应液(含50 g/L脱脂奶粉, 1 g/L Triton X-100), 冰上反应30 min. 用Triton X-100 PBS洗1次, 细胞沉淀用1 mL含1.5 mg/L Hoechst 33258的PBS悬浮, 流式细胞仪测定凋亡细胞. 试验设3个平行孔, 混合后上机检测. 利用Hoechst 33342染色法, 工作浓度4 mg/L, 染色时间10 min, 收获细胞, PBS洗涤1次后荧光显微镜观察细胞凋亡的形态.

细胞分别用0.05, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2 mmol/L ALA处理, 荧光分光光度计测得的PpIX荧光信号值, 按所加入的PpIX标准量换算成浓度, 然后除以细胞总蛋白量, 得出PpIX绝对浓度值(图1). 两种细胞均随ALA浓度的增加, 细胞内PpIX产量增大. 当ALA浓度达到1 mmol/L时, 细胞内PpIX浓度接近饱和, 缓慢进入平台期, 故以后的实验均使用1 mmol/L的ALA. 高分化食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-450与低分化KYSE-70相比具有更强的PpIX合成或积累能力(图1), 两者从0.5 mmol/L ALA浓度点开始就具有显著性差异(315.2±88.3 vs 156.9±79.2, P<0.05).

KYSE-450与KYSE-70细胞用1 mmol/L ALA处理, 分别给予不同剂量的红光照射, 24 h后检测细胞存活率曲线. 虽然高分化KYSE-450细胞含有较高浓度的PpIX, 但对PDT反应迟钝. 相反具有低浓度PpIX的KYSE-70则对PDT更敏感. 当光剂量为3.6 J/cm2时, KYSE-450细胞存活率为88.0%, KYSE-70仅为25.2%, 两者差异显著(88.0±7.4 vs 25.2±4.9, P<0.01, 图2). 为进一步证实该实验结果, 我们应用不同剂量的蓝光照射, 也得到了相似的结果(97.4±7.3 vs 40.8±4.2, P<0.01, 图3).

KYSE-450和KYSE-70分别使用的光剂量为7.2 J/cm2和3.6 J/cm2, 两者细胞死亡率均为75%左右. PDT后24 h KYSE-450细胞凋亡率为12.5%, KYSE-70为23.2%. 虽然低分化细胞的凋亡多于高分化细胞, 但两者主要以细胞坏死为主. PDT处理后24 h的细胞用Hoechst 33342染色, 荧光显微镜观察, 结果非凋亡细胞胞核染色均一, 凋亡细胞胞核明显凝集变亮, 呈边缘化或裂解. 显微镜下记数的细胞凋亡率基本与TdT法结果相符(图4).

5-ALA本身不具有光激活作用, 他是内源性光敏物质PpIX的前体. 细胞利用ALA合成血红素(heme)的过程中, 产生中间产物PpIX. 此合成步骤一部分在胞质, 一部分在线粒体内进行. 细胞内的ALA主要是由甘氨酸和琥珀酰辅酶A在ALA合成酶的催化下合成. ALA在胞质中经过胆色素原→尿卟啉→粪卟啉→原卟啉原Ⅲ途径, 进入线粒体内形成PpIX, 最后在亚铁原卟啉合成酶(ferrochelatase)催化下成为血红素[15-17]. 在血红素合成过程中存在两个限速步骤[18], 第一个是ALA产生步骤, 受heme的反馈抑制. 当有外源性ALA存在的情况下则解除了这种反馈抑制, 促使代谢效率提高, 增强了PpIX的合成. 另外一个限速步骤是由PpIX生成heme的过程, 由限速酶亚铁原卟啉合成酶调控. 肿瘤细胞内这些代谢酶活性可存在差异, 结果造成PpIX在线粒体内的积累[12]. 本结果显示, 高分化和低分化的食管鳞癌细胞当有外源性ALA存在的情况下, 均可显著提高细胞内PpIX的产量, 且细胞内PpIX浓度依赖于环境中ALA的浓度. 但两者PpIX的积累幅度却有明显差异, 高分化KYSE-450细胞能产生更高浓度的PpIX(图1). Ortel et al[19]证实初级小鼠角质细胞(primary mouse keratinocyte)的分化能增强细胞内PpIX的合成, 与我们的实验结果相似. Krieg et al[20]也发现高分化人膀胱癌细胞RT4 PpIX累积浓度也高于低分化的J82细胞, 经测定细胞内亚铁原卟啉合成酶的活性, 发现RT4细胞远低于J82细胞, 说明高分化RT4细胞线粒体内由PpIX生成血红素的速率降低, 提示细胞分化状态影响了血红素代谢过程, 并影响到PpIX的胞内浓度. 由于PpIX在线粒体内合成, 细胞需要把PpIX的前体粪卟啉原Ⅲ穿膜运输至线粒体内的PpIX合成位点, 此转运功能由线粒体外膜蛋白PBR(peripheral benzodiazepine receptor)承担[21-23], 因而细胞中PBR蛋白表达水平的高低有可能决定了PpIX的合成效率或线粒体吸收结合光敏剂的能力. Morgan et al[24]报道高分化的皮肤癌细胞具有高水平的PBR蛋白表达, 分化差的癌细胞和浸润型癌细胞PBR表达很低, 这也可能是造成高分化细胞积累较高浓度PpIX的原因之一. 本研究中食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-450和KYSE-70在PpIX积累能力的差别, 是因Heme代谢过程中酶活性的差异引起, 还是PBR水平不同而引起, 是需进一步阐明的问题.

既然高分化细胞含高浓度的PpIX, 理应对PDT更加敏感. 理由是PDT产生的单态氧数量与光敏剂分子数目有关, 因而PDT的细胞毒性强度应与光敏剂浓度相关. 许多实验亦证实如此. 据文献报道在结肠腺癌细胞PpIX的产量为高分化细胞(CaCo2)>中分化细胞(HT29)>低分化细胞(SW480), PDT效果相应也是高分化细胞>中分化细胞>低分化细胞[25]. Ortel et al[26]用诱导剂诱导前列腺癌LNCaP细胞的分化能显著提高细胞内PpIX浓度, 并相应增强了PDT的杀伤作用. 但本研究中KYSE-450虽然PpIX产量高于KYSE-70, 但对PDT的应答明显差于KYSE-70细胞, 无论红光PDT还是蓝光PDT均有一致结果(图2, 3). 考虑到由ALA产生的内源性PpIX主要分布在线粒体[27,28], 我们也探讨了外源性PpIX对PDT效应的影响. 外源性PpIX在细胞内成弥漫性分布, 完全不同于内源性PpIX的分布形式. 在同样的实验条件下, KYSE-450仍然比KYSE-70具有明显的抵御PDT的能力. 另外我们实验室发现高分化结肠腺癌细胞HCCP 2998 PpIX产量也显著高于低分化结肠腺癌细胞Colo 205, 但PDT(蓝光, 波长405 nm)效果却相反, 与本实验结果相类似(Shahzidi et al), 提示PDT的光毒性效果不仅与PpIX积累能力有关, 还与细胞种类及其生物学特性相关. 肿瘤细胞在分化过程中, 有可能形成了某一种机制, 增强了抵抗PDT或其他放疗化疗的能力. 研究并确切了解这种机制有重要的实际临床意义. PDT对肿瘤细胞的杀伤作用大多是通过诱导凋亡与坏死两种机制的结合, 而非单一的凋亡或单一的坏死[29]. PDT后癌细胞死亡是以凋亡为主还是以坏死为主, 与光敏剂的种类和剂量, 所用光的波长和剂量以及细胞种类和生物学特性等许多因素有关[30]. 我们发现ALA-PDT诱导的食管鳞癌细胞KYSE-450和KYSE-70的细胞凋亡率分别是12.5%和23.2%(TdT法), 荧光显微镜下可发现胞核凝集及边缘化等典型的凋亡特征, 但多数细胞死亡方式为坏死. 尽管如此, 本实验条件下高分化KYSE-450细胞凋亡率低于低分化KYSE-70细胞的现象, 至少可提示高分化肿瘤细胞对PDT的抵御作用部分是通过抑制凋亡而产生, 增强细胞对凋亡的敏感性有可能部分改善癌细胞对PDT的应答.

PDT是近20 a来应用于浅表肿瘤临床治疗的一种非手术替代疗法, 在某些生物学性状如皮肤肿瘤和癌前病变的临床已成为常规性治疗措施, 但在另一些领域仍是空白. 影响PDT疗效的因素很多, 除光敏剂、光及分子氧以外, 肿瘤细胞的生物学状以及某些凋亡相关基因的表达活性也可能影响PDT效果. 理解PDT效应的确切机制及如何增强PDT临床治疗效果是当前PDT研究中的重点. 以往的研究报道提示肿瘤细胞的不同分化状态能造成不同的细胞内光敏剂产生水平和累积水平, 进而造成PDT效应的差异. 本研究应用高、低分化的食管鳞癌细胞系, 以ALA作为光敏剂, 研究食管鳞癌细胞分化状态对内源性光敏剂PpIX产量的影响及对PDT的应答.

该研究结果对解释不同临床患者的不同PDT疗效甚至预示PDT预后具有指导意义.

1 Ortel B, Chen N, Brissette J, Dotto GP, Maytin E, Hasan T. Differentia-tion-specific increase in ALA-induced protopor-phyrin IX accumulation in primary mouse keratinocytes. Br J Cancer 1998; 77: 1744-1751

2 Krieg RC, Fickweiler S, Wolfbeis OS, Knuechel R. Cell-type specific protopor-phyrin IX metabolism in human bladder cancer in vitro. Photochem Photobiol 2000; 72: 226-233

选题比较新颖, 研究内容较重要, 研究提供了充足有意义的信息, 有一定的临床指导价值, 研究对象为食管鳞癌细胞, 符合伦理学要求.

电编: 张敏 编辑:潘伯荣 审读:张海宁

| 1. | Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Peng Q. Photodyna-mic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889-905. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Luksiene Z. Photodynamic therapy: mechanism of action and ways to improve the efficiency of treat-ment. Medicina (Kaunas). 2003;39:1137-1150. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Yamaguchi S, Tsuda H, Takemori M, Nakata S, Nishimura S, Kawamura N, Hanioka K, Inoue T, Nishimura R. Photodynamic therapy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Oncology. 2005;69:110-116. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Morton CA. Methyl aminolevulinate (Metvix) pho-todynamic therapy - practical pearls. J Dermatolog Treat. 2003;14:23-26. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Chen JY, Peng Q, Jodl HJ. Infrared spectral compa-rison of 5-aminolevulinic acid and its hexyl ester. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc. 2003;59:2571-2576. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Mitra S, Foster TH. Photophysical parameters, photosensitizer retention and tissue optical properties completely account for the higher photodynamic efficacy of meso-tetra-hydroxyphenyl-chlorin vs Photofrin. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:849-859. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Peng Q, Berg K, Moan J, Kongshaug M, Nesland JM. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy: principles and experimental research. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;65:235-251. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Rancan F, Wiehe A, Nobel M, Senge MO, Omari SA, Bohm F, John M, Roder B. Influence of substitutions on asymmetric dihydroxychlorins with regard to in-tracellular uptake, subcellular localization and pho-tosensitization of Jurkat cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2005;78:17-28. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Schieke SM, von Montfort C, Buchczyk DP, Timmer A, Grether-Beck S, Krutmann J, Holbrook NJ, Klotz LO. Singlet oxygen-induced attenuation of growth factor signaling: possible role of ceramides. Free Radic Res. 2004;38:729-737. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Du HY, Olivo M, Tan BK, Bay BH. Hypericin-mediated photodynamic therapy induces lipid per-oxidation and necrosis in nasopharyngeal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1401-1405. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Moor AC. Signaling pathways in cell death and survival after photodynamic therapy. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2000;57:1-13. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Peng Q, Moan J, Warloe T, Iani V, Steen HB, Bjorseth A, Nesland JM. Build-up of esterified aminolevulinic-acid-derivative-induced porphyrin fluorescence in normal mouse skin. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;34:95-96. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bhasin G, Kausar H, Athar M. Protoporphyrin-IX accumulation and cutaneous tumor regression in mice using a ferrochelatase inhibitor. Cancer Lett. 2002;187:9-16. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Sauren M, Pirogova E, Cosic I. RRM analysis of pro-toporphyrinogen oxidase. Australas Phys Eng Sci Med. 2004;27:174-179. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Friesen SA, Hjortland GO, Madsen SJ, Hirschberg H, Engebraten O, Nesland JM, Peng Q. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic detection and therapy of brain tumors (review). Int J Oncol. 2002;21:577-582. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Fukuda H, Casas A, Batlle A. Aminolevulinic acid: from its unique biological function to its star role in photodynamic therapy. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2005;37:272-276. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Collaud S, Juzeniene A, Moan J, Lange N. On the selectivity of 5-aminolevulinic acid-induced proto-porphyrin IX formation. Curr Med Chem Anti-Canc Agents. 2004;4:301-316. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Tsai T, Hong RL, Tsai JC, Lou PJ, Ling IF, Chen CT. Effect of 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated photody-namic therapy on MCF-7 and MCF-7/ADR cells. Lasers Surg Med. 2004;34:62-72. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Ortel B, Chen N, Brissette J, Dotto GP, Maytin E, Hasan T. Differentiation-specific increase in ALA-induced protoporphyrin IX accumulation in primary mouse keratinocytes. Br J Cancer. 1998;77:1744-1751. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Krieg RC, Fickweiler S, Wolfbeis OS, Knuechel R. Cell-type specific protoporphyrin IX metabolism in human bladder cancer in vitro. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;72:226-233. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Kessel D, Antolovich M, Smith KM. The role of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in the apoptotic response to photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:346-349. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Morris RL, Varnes ME, Kenney ME, Li YS, Azizuddin K, McEnery MW, Oleinick NL. The peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in photodyna-mic therapy with the phthalocyanine photosen-sitizer Pc 4. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;75:652-661. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Dougherty TJ, Sumlin AB, Greco WR, Weishaupt KR, Vaughan LA, Pandey RK. The role of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor in photodyna-mic activity of certain pyropheophorbide ether pho-tosensitizers: albumin site II as a surrogate marker for activity. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;76:91-97. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Morgan J, Oseroff AR, Cheney RT. Expression of the peripheral benzodiazepine receptor is decreased in skin cancers in comparison with normal skin. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:846-856. [PubMed] |

| 25. | Krieg RC, Messmann H, Schlottmann K, Endlicher E, Seeger S, Scholmerich J, Knuechel R. Intracellular localization is a cofactor for the phototoxicity of protoporphyrin IX in the gastrointestinal tract: in vitro study. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;78:393-399. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Ortel B, Sharlin D, O'Donnell D, Sinha AK, Maytin EV, Hasan T. Differentiation enhances aminolevu-linic acid-dependent photodynamic treatment of LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Br J Cancer. 2002;87:1321-1327. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Peng Q, Warloe T, Berg K, Moan J, Kongshaug M, Giercksky KE, Nesland JM. 5-Aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy. Clinical research and future challenges. Cancer. 1997;79:2282-2308. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Gabeler EE, Sluiter W, van Hillegersberg R, Edix-hoven A, Schoonderwoerd K, Statius van Eps RG, van Urk H. Aminolaevulinic acid-induced proto-porphyrin IX pharmacokinetics in central and peri-pheral arteries of the rat. Photochem Photobiol. 2003;78:82-87. [PubMed] |

| 29. | Oleinick NL, Morris RL, Belichenko I. The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy: what, where, why, and how. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:1-21. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Peng Q, Warloe T, Moan J, Godal A, Apricena F, Giercksky KE, Nesland JM. Antitumor effect of 5-aminolevulinic acid-mediated photodynamic therapy can be enhanced by the use of a low dose of photofrin in human tumor xenografts. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5824-5832. [PubMed] |