修回日期: 2005-07-04

接受日期: 2005-07-06

在线出版日期: 2005-09-28

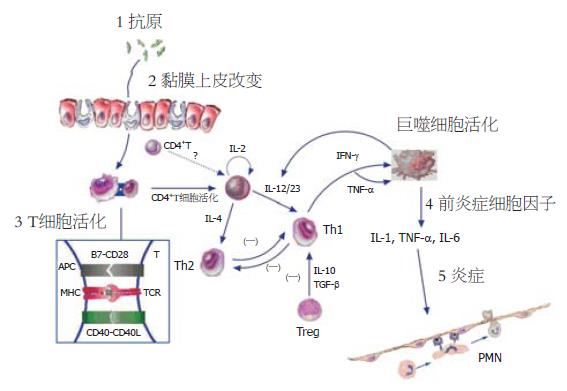

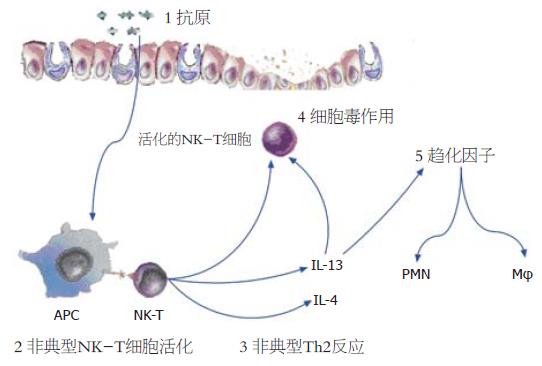

肠黏膜免疫调节紊乱导致炎症性肠病的发生. 肠道共生的微生物抗原刺激肠黏膜T细胞, CD4+T细胞在IL-12的作用下分化为Th1, 形成IFN-γ, TNF-α升高的Th1型黏膜炎症, 表现与Crohn病相似; CD4+T细胞或非典型NKT细胞活化后, 分泌IL-13, IL-4, IL-5, 形成Th2型黏膜炎症, 表现与溃疡性结肠炎相似. 调节性T细胞Th3, Tr1和CD4+CD25+ T细胞通过分泌TGF-β和IL-10等作用抑制肠黏膜免疫反应, 维持肠黏膜平衡.

引文著录: 王旭丹, 袁学勤. 肠黏膜免疫调节紊乱介导炎症性肠病的发生. 世界华人消化杂志 2005; 13(18): 2257-2262

Revised: July 4, 2005

Accepted: July 6, 2005

Published online: September 28, 2005

N/A

- Citation: N/A. N/A. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2005; 13(18): 2257-2262

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v13/i18/2257.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v13.i18.2257

炎症性肠病(inflammatory bowel disease, IBD)是一组病因不明的慢性肠道炎症性疾病, 主要包含了两个独立的疾病, 溃疡性结肠炎(ulcerative colitis, UC)和克隆病(crohn's disease, CD), 二者在临床表现和病理特点上各不相同. 目前普遍认为IBD的产生主要来自于黏膜免疫、相关基因和环境因素, 其中免疫因素是IBD目前研究最活跃的领域. 采用自发的动物模型和基因工程动物模型及可诱导的动物模型为研究IBD的免疫机制的提供了重要的工具, 并取得大量有价值的研究成果.

淋巴细胞异常活化参与了IBD的发生. 淋巴细胞的活化需要抗原, 越来越多的资料表明, 肠道微生物, 尤其是共生细菌承担了启动黏膜免疫细胞活化的抗原的角色. 人类肠道黏膜表面分布了大量的微生物, 这些微生物从人一出生就定居于此. 从某种意义上说, 这些共生的微生物可能已成为人体成分的一部分, 它们的某些抗原成分甚至能进入人体内环境, 并可能经过胸腺处理, 以至于等同于自身抗原[1]. 因此, 正常个体的血液和黏膜的单个核细胞对自身来源的微生物并不发生免疫应答, 但对其它个体肠道的微生物群则有反应, 即使是相同的品系的微生物也是这样[2]. 但IBD患者结肠黏膜的单个核细胞在自身同源的肠道细菌刺激下也会发生增生, 症状缓解的患者则失去增生能力[3]. 多项证据证明了IBD的产生与肠道微生物密切相关. 如在普通饲养条件或无特定病原体条件下建立的动物结肠炎, 在无菌条件下不能建立[4]. 预先用抗生素处理可以减轻消炎痛结肠炎、DSS(dextran sulfate sodium, 硫酸葡聚糖钠)结肠炎、TNBS(trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid, 三硝基苯磺酸)结肠炎的肠道炎症反应; 如未经抗生素处理, TNBS在注入24 h后, 即可观察到动物结肠黏膜和黏膜下层有细菌入侵现象[5]. 研究表明, 虽然共生微生物中的厌氧菌较需氧菌产生更为严重的黏膜损害和炎症, 但共生的厌氧菌和需氧菌的复杂的共同作用为免疫性结肠炎症的产生提供了持续的抗原性刺激[6].

究竟是何种抗原成分启动了肠道黏膜免疫反应一直为研究者所关注. 将肝螺杆菌(Helicobacter hepaticus)接种于无特定病原体的IL-10-/-小鼠中可诱导的盲肠和结肠炎, 与炎症相关的Th1细胞可与肝螺杆菌裂解液中的可溶性抗原SheLAg发生反应, 且SheLAg特异的CD4+T细胞的过继转移可导致肝螺杆菌感染的RAG-/-小鼠出现结肠炎, 但在没有感染肝螺杆菌的RAG-/-小鼠并不出现. 这些CD4+T细胞克隆中的其中一个识别肝螺杆菌中的一个718个氨基酸构成的鞭毛钩状蛋白, 其识别表位为VFEGGRASFNSDGSL, 这是迄今为止获得的第一份导致结肠炎的单一的细菌抗原成分[7]. 临床研究也得到了相似的结论[8].

肠黏膜屏障功能的完整是维持肠黏膜正常功能的基础. 黏膜屏障功能的缺陷有利于微生物抗原进入肠黏膜固有层, 诱发异常的黏膜免疫应答. 例如, 预先用洗涤剂处理肠黏膜去除上皮磷脂层并减少肠黏膜的表面疏水性, 将增加DSS诱导的大鼠黏膜上皮的炎症损伤; 相反, 用表面活性脂局部处理则减少了DSS结肠炎的易感性, 并有效地保护上皮[9]. 效应T细胞的活化是肠黏膜免疫及其后续炎症的起点. 外周T细胞亚群中, 已明确CD4+T细胞是导致肠黏膜炎症的主要效应细胞, 因为到目前为止所研究的所有结肠炎模型中黏膜组织浸润中最主要的细胞类型即为CD4+T细胞; 而且在一些研究中, 体内删除CD4+T细胞, 炎症即好转[10]. CD4+T细胞的活化需要抗原特异性信号以及协同刺激信号. 抗原特异性信号涉及到数量庞大的肠道微生物抗原, 研究有一定的难度. 协同刺激信号在炎症性肠病中的作用报道较多, 如IBD中CD40和CD40L表达显著增强, 并能促进IL-12和TNF-α的释放[11].

CD4+T细胞获得充分的活化信号后, 在IL-12存在的情况下极化为Th1并分泌IFN-γ介导肠黏膜炎症, 此类结肠炎体内存在高水平的IFN-γ, IL-2等细胞因子, 故为Th1型炎症. 一般而言, CD的炎症特征在肉眼和光镜水平下与Th1介导的黏膜炎症模型相似. IL-12在Th极化为Th1中起到了关键作用. 单核巨噬细胞针对细菌、细菌产物或寄生虫反应是IL-12的主要来源. 如CD患者病灶原位巨噬细胞产生大量的IL-12, 而UC患者则无此现象, 且活化的CD4+T细胞主要分泌IFN-γ, 但产生IL-4的T细胞很少[12,13]. 与健康人比较, CD患者的炎症损伤处分离的巨噬细胞体外产生的IL-12增加[14], 而UC患者产生的IL-12则减少. IL-23是新发现的促进T细胞向Th1极化的细胞因子, 由于IL-23与IL-12共用了一个亚单位p40, 故二者之间具有相似的生物学作用, 但在刺激Th1记忆细胞方面IL-23比IL-12更为有效, 因此IL-23主要是起到维持Th1介导的炎症反应的作用[15]. 最近发现IL-21也有助于CD患者的Th1反应的建立过程[16]. TNBS结肠炎是典型的Th1型肠黏膜炎症模型, 其肠道中可观察到与CD的病理特点非常相似的炎性细胞在各层中浸润并伴有肉芽肿的特征. Neurath et al发现该模型中分离的巨噬细胞产生大量的IL-12, 淋巴细胞产生大量的IFN-γ和IL-2. 用抗IL-12抗体治疗就可完全阻断TNBS诱导的结肠炎的发生, 或者使已建立模型的小鼠炎症损伤彻底地消失[17]. 这一事实证明, TNBS结肠炎是由IL-12启动, T淋巴细胞分化为Th1细胞释放IFN-γ所介导. SCID过继转移结肠炎模型是另一种典型的Th1型肠黏膜炎症模型, 将高表达CD45RB分子的CD4+T细胞(CD4+CD45RBhi, 初始T细胞)过继转移给SCID小鼠或Rag2-/-小鼠即可建立[18]. SCID结肠炎的T细胞反应也是由IL-12驱动, IFN-γ介导[19]. 尽管CD45RBhiT细胞占据了SCID小鼠的小肠和大肠, 但炎症仅局限于结肠, 而且还发现在一个近乎无菌的环境中饲养的小鼠接受过继转移的细胞后炎症水平降低, 这表明结肠中的微生物为黏膜炎症提供了抗原刺激[20].

Th1发挥炎症作用是通过分泌IFN-γ, IL-2和TNF-β等细胞因子实现的. 其中IFN-γ在Th1反应中起中心角色. Th1细胞过度产生IFN-γ的原因可能与T-bet和STAT4两个分子有关. T-bet是T-box蛋白, 当其在T细胞上过度表达时, 可使T细胞执行高水平的IFN-γ反应、较低IL-4反应[21]. 即使在缺乏STAT-4的细胞中T-bet过度表达也能导致IFN-γ反应, 该因子可能是Th1分化的分子开关. STAT4也是Th1分化的必需的因子, 可能扮演IFN-γ转录因子以及维持Th1细胞生存因子的角色. TNP(TNBS半抗原的表位)偶联的KLH在正常小鼠上并未诱导出结肠炎, 但在STAT4的转基因小鼠则能诱导Th1型结肠炎, 表明结肠炎与STAT4的异常表达相关; 来自于这些小鼠的脾细胞体外与自身来源的微生物接触后增生, 增生的T细胞转移到SCID小鼠上, 可诱导结肠炎; 初始但过度表达T-bet(通过表达T-bet的反转录病毒感染)的T细胞过继转移到SCID小鼠上, 能诱导结肠炎加速建立[22]. CD患者也同样存在这两个分子的异常, 如炎症组织中的T细胞的核提取物中的STAT4和T-bet含量显著增加, 且组织中Th1细胞数量也显著增加的, 因为这些T细胞表达Th1细胞的特征性受体IL-12Rβ2[23,24]. 根据这些发现, CD患者炎症组织中T细胞产生大量的IFN-γ, 但IL-4的产量降低也就不奇怪了. Th1细胞释放的IFN-γ能活化单核巨噬细胞, 使之释放前炎性细胞因子TNF-α、IL-6、IL-1参与炎症过程, 其中TNF-α直接参与了Th1炎症反应, 这一推测已被TNF△ARE小鼠结肠炎模型所证实[25]. 该模型与CD极为相似, 其炎症很可能是由微生物的LPS诱导TNF-α的产生并启动和维持.

虽然CD主要由Th1型免疫反应所介导, 但也不是绝对的. 新近的研究发现, SAMP1/YitFc小鼠自发性末端回肠炎的病理特点与CD相似, 但炎症既有Th1细胞参与, 也有Th2细胞参与. Th1细胞因子IFN-γ和TNF参与回肠炎的初始化, 中和IFN-γ可干扰淋巴细胞扩增及有利于慢性炎症的终止; 当进展为慢性回肠炎时, Th2型细胞因子IL-5和IL-13显著增加, 封闭IL-4能显著改善回肠炎[26]. 大量的IFN-γ产生可诱导吞噬细胞活化并释放前炎症因子, 如IL-1、TNF-α等. 这些细胞因子活化血管内皮细胞血管黏附分子的上调, 并募集白细胞和单核细胞进入黏膜固有层. 活化的白细胞和单核细胞在局部的浸润并释放炎症介质, 进一步放大了炎症并导致组织损伤. 多种生物活性物质如蛋白酶、PAF、NO、前列腺素、反应性氧中介物等对组织的损伤负有责任[27]. 图1中我们对CD的主要发病机制进行了简单的归纳.

Th2细胞介导的结肠炎具有多种表现形式, 其炎症类型与Th1结肠炎不同, 与CD比较更像是UC. 因此推测UC是Th2细胞介导的疾病, 但支持这一观点的证据并不充分. 虽然UC中IL-12/IFN-γ量并未增加, 但Th2特征性细胞因子IL-4也没有增加, 且损伤组织中的炎症也并不像常见的以嗜酸性粒细胞浸润为主要特征的Th2型炎症. 事实上, 唯一被报道增加的Th2型的细胞因子是IL-5[12,13,28]. 当然, 尚有其它的一些证据认为UC是Th2介导的肠道炎症性疾病: (1)在UC患者比CD患者体内存在更多的自身抗体, 如抗中性粒细胞胞质抗体(pANCA)和抗原肌球蛋白抗体, Th2细胞能为B细胞活化并分化为浆细胞和产生抗体提供更大的帮助; (2)UC中增加的的自身抗体主要为与Th2相关的抗体类型, 如IgG1和IgG4; (3)EB病毒诱导的基因3(EBI3)编码的产物现在被鉴定为Th2型细胞因子, 这种细胞因子在UC中而不是在CD中增加[29]. 尽管UC的组织学表现与Th2细胞介导的实验性结肠炎密切相关, 但目前把UC归纳为Th2型疾病似乎还不成熟. 实验性结肠炎表现为Th2型的主要有TCR-α缺陷小鼠结肠炎和恶唑酮(oxazolone)诱导的结肠炎. TCR-α链缺乏的小鼠结肠炎模型是目前研究的最好的Th2介导的炎症模型, 其炎症损伤相对表浅, 偶尔会扩展到黏膜下层. 组织学表现为隐窝延长、变形, 偶见隐窝脓肿, 很少出现透壁性的裂隙和肉芽肿, 故与UC相似; 且模型小鼠循环中能检测到pANCA及其他自身抗体[30]. 由于TCR-α链缺失, 故此模型小鼠的T细胞亚群主要是γδTCR的T细胞, 也混杂了少量的ββTCR的T细胞, 后来证实ββTCR的T细胞是导致炎症的效应细胞[31], 该模型的效应细胞因子是IL-4而不是IFN-γ[32]. 半抗原恶唑酮可在SJL/J小鼠中诱导出类似UC的实验性结肠炎, 炎症位于远端结肠, 伴有溃疡[33]. 刺激炎症组织中CD4+T细胞能产生大量的IL-4和IL-5, 但IFN-γ正常或者减少; 抗IL-4治疗能显著缓解疾病, 而抗IL-12治疗无效或者恶化. 研究发现非典型NKT细胞在恶唑酮结肠炎扮演重要角色: 恶唑酮与非典型的MHC I类分子CD1d的结合后递呈给NKT细胞, 导致NKT应答并分泌IL-13, 中和IL-13可阻断结肠炎. 因此, 恶唑酮结肠炎可能是NK-T活化并分泌的IL-13启动非典型的Th2反应, 进而导致黏膜炎症[34]. 在UC患者中存在类似情况, 非典型的NKT细胞在抗-CD2/抗-CD28抗体刺激下或者转染表达CD1d的B细胞刺激下可产生了大量的IL-13, 并对HT-29系上皮细胞具有细胞毒作用; IL-13能促进此细胞毒作用. 因此, 研究者推测UC的发生可能是表达CD1d的树突状细胞和上皮细胞递呈抗原给NKT细胞, NKT细胞活化后分泌IL-13并开始溶解上皮细胞, 导致上皮细胞减少、溃疡以及上皮屏障出现裂口; 此后, 肠道微生物进入固有层以及IL-13诱导趋化因子产生导致后续的更为严重的炎症反应(图2)[35].

炎症效应T细胞活化后, 表面开始表达CTLA-4和PD-1等分子并向胞内传递抑制信号, 防止免疫细胞的过度活化. 例如在UC和CD患者的病变结肠中发现PD-1在T细胞上的表达显著增加; SCID过继转移小鼠结肠炎模型中, PD-1阳性的细胞在炎症结肠黏膜也比对照组显著增加[36]. 调亡也是效应细胞重要的转归, 但IBD患者往往存在调亡的障碍. 例如, 虽然IBD的肠道炎症中的固有层T细胞上Fas的表达并不比对照低, 但能抵抗Fas诱导调亡, 其原因可能与IL-6、IL-12和TNF-α等细胞因子有助于T细胞直接抵抗调亡相关[37,38], 因为在小鼠结肠炎中使用IL-12, TNF-α以及IL-6受体的抗体处理可诱导T细胞调亡[39-41]. 临床也观察到抗TNF-α抗体治疗可抑制CD的疾病活动[42], 这是抗体诱导肠道中T细胞调亡的结果[43].

正常的肠黏膜中效应细胞和调节细胞处在动态平衡状态, 保持肠黏膜免疫系统稳定. 如果效应细胞的作用远远超过调节性细胞, 或者是调节性细胞不足, 均可打破二者平衡, 导致肠黏膜炎症. 越来越多的证据表明调节性细胞可通过直接接触、释放细胞因子达到抑制免疫反应的作用. 如在研究口服诱导耐受的过程中发现的Th3细胞可通过分泌的TGF-β在黏膜免疫中承担调节作用[44]. TGF-β具有广泛的抗炎症作用, 能抑制Th1和Th2细胞的活化, 是自身免疫调节的重要因素. 另一种调节型T细胞Tr1可分泌高水平的IL-10、低水平的IL-2, 不产生IL-4, 增生能力很弱[45]. 肠道内环境的稳定需要Tr1, 当肠道病原体被清除后, Tr1可通过IL-10下调炎症反应, 如Tr1细胞可抑制SCID小鼠建立过继性结肠炎[46,47]. 最近鉴定出的CD4+CD25+T调节细胞是目前研究的热点. 胸腺来源的CD4+CD25+T调节型T细胞对于维持自身耐受极为必要. 骨髓转移Tgε26小鼠(BMTgε26)所建立的结肠炎模型中, 肠系膜淋巴结中CD4+CD25+T细胞减少, 其原因可能是胸腺异常所致. 正常小鼠的CD4+CD25+T细胞转移到BMTgε26小鼠可使肠系膜淋巴结中的T细胞数和功能正常, 并阻止了结肠炎的发生[48].

CD4+CD25+T细胞发挥抑制作用需要细胞间的接触. 大部分CD4+CD25+T细胞以TGF-β蛋白前体形式产生细胞表面的TGF-β, 表面TGF-β可通过细胞间的接触介导抑制作用; 但如果刺激信号强烈, 也可分泌TGF-β和IL-10发挥作用[49]. CD4+CD25+T细胞也利用CTLA-4信号[50]、GITR信号[51]介导的免疫抑制效应. 此外, CD4+CD25+调节型T细胞体内也可以调控树突状细胞的活化达到免疫抑制效应[50]. CD4+CD25+调节型T细胞在SCID小鼠结肠模型的MLN和炎性结肠中增生, 它们定居于CD11c+细胞和病理性T细胞之间, 与这些细胞均有广泛联系, 这有利于调节作用的发挥[52]. CD4+CD25+调节型T细胞对SCID小鼠结肠炎的抑制作用并非是抑制病理性T细胞实现的, 似乎是诱导了效应T细胞的灭活状态、或潜在性诱导Th2效应, 因为当移除调节型T细胞后, 效应T细胞体外同样对刺激有反应, 分泌的IFN-γ也同样多[53]. 小鼠CD4+CD25+T细胞选择性表达建立T细胞抑制效应的关键因子FoxP3[54]. FoxP3参与X伴随的隐性染色体病IPEX, 这是一种自身免疫性和炎症性的肠病. 小鼠的FoxP3只在CD4+CD25+调节型T细胞上表达, 在活化的CD4+CD25-T细胞上并不被诱导, 但用反转录病毒引入FoxP3后, 天然的CD4+CD25-T细胞可以转化为调节型T细胞, 因此FoxP3是小鼠CD4+CD25+T细胞建立所必须的. 人类CD4+CD25+调节型T细胞也表达FoxP3, CD25-T细胞并不表达[55]. CD4+CD25+作为调节型T细胞与他们表达FoxP3是分不开的.

此外, 肠黏膜上皮层独有的CD4+CD8αα+的双阳性T细胞(TCRαβ+)以IL-10依赖的方式抑制Th1T细胞被动转移给RAG-1-/-小鼠所诱导的结肠黏膜炎症[56]; γδT细胞分泌角质细胞生长因子(KGF)促进DSS结肠炎损伤的上皮细胞恢复完整性[57], 还可通过促进中性粒细胞增生并迁移到黏膜, 以拮抗单个核细胞在炎症部位的浸润, 因为单个核细胞在黏膜的浸润所导致的炎症往往更加严重和致命[58]; 典型的NKT细胞以CD1d限制性方式活化, 活化后调节肠道炎症[59], 其调节机制可能与调整了肠道黏膜Th1/Th2反应, 使之保持平衡有关[60]; B细胞[61]、CD8+T细胞[62,63]中某些亚群也参与了肠黏膜免疫的调节.

总之, 虽然对炎症性场病的免疫机制已经有了广泛而深入地了解, 但大量而有趣的研究来自于动物模型, 与人类IBD毕竟不能完全等同. 因此, 人类IBD的研究尚需进一步加强. 在今后的研究中, 仍有很多问题亟待解决. 如病理性抗原的寻找和鉴定, 调节性T细胞的分类、功能和作用机制, 个体遗传与黏膜免疫反应关系等. 但从目前已知的成果中, 我们也能够得到一些治疗IBD的有益启示. 如调节Th1/Th2平衡, 采用肠道内鞭毛寄生虫感染治疗CD短期安全而又有效, 其治疗机制可能是通过寄生虫感染诱导体内出现强烈的Th2反应, 从而抑制CD患者的Th1免疫效应[64]; 再如阻断效应T细胞活化或增强调节性细胞功能, 以维持肠道中效应细胞与调节细胞间的平衡, 采用IL-12p40-IgG2b融合蛋白拮抗IL-12信号显著改善TNBS诱导的结肠炎, 并抑制CD患者固有层单个核细胞增生和释放IFN-γ、促进其调亡[65].

电编: 张敏 编辑:潘伯荣 审读:张海宁

| 1. | Karlsson MR, Kahu H, Hanson LA, Telemo E, Dahlgren UI. Neonatal colonization of rats induces immunological tolerance to bacterial antigens. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:109-118. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 2. | Duchmann R, Neurath MF, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH. Responses to self and non-self intestinal microflora in health and inflammatory bowel disease. Res Immunol. 1997;148:589-594. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Panés J. Inflammatory bowel disease: pathogenesis and targets for therapeutic interventions. Acta Physiol Scand. 2001;173:159-165. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 4. | Taurog JD, Richardson JA, Croft JT, Simmons WA, Zhou M, Fernández-Sueiro JL, Balish E, Hammer RE. The germfree state prevents development of gut and joint inflammatory disease in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Exp Med. 1994;180:2359-2364. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 5. | Guarner F, Malagelada JR. Role of bacteria in experimental colitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:793-804. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Rath HC, Schultz M, Freitag R, Dieleman LA, Li F, Linde HJ, Schölmerich J, Sartor RB. Different subsets of enteric bacteria induce and perpetuate experimental colitis in rats and mice. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2277-2285. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Kullberg MC, Andersen JF, Gorelick PL, Caspar P, Suerbaum S, Fox JG, Cheever AW, Jankovic D, Sher A. Induction of colitis by a CD4+ T cell clone specific for a bacterial epitope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15830-15835. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Lodes MJ, Cong Y, Elson CO, Mohamath R, Landers CJ, Targan SR, Fort M, Hershberg RM. Bacterial flagellin is a dominant antigen in Crohn disease. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1296-1306. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 9. | Lugea A, Salas A, Casalot J, Guarner F, Malagelada JR. Surface hydrophobicity of the rat colonic mucosa is a defensive barrier against macromolecules and toxins. Gut. 2000;46:515-521. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Okamoto S, Watanabe M, Yamazaki M, Yajima T, Hayashi T, Ishii H, Mukai M, Yamada T, Watanabe N, Jameson BA. A synthetic mimetic of CD4 is able to suppress disease in a rodent model of immune colitis. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:355-366. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Danese S, Sans M, Fiocchi C. The CD40/CD40L costimulatory pathway in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2004;53:1035-1043. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Monteleone G, Biancone L, Marasco R, Morrone G, Marasco O, Luzza F, Pallone F. Interleukin 12 is expressed and actively released by Crohn's disease intestinal lamina propria mononuclear cells. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1169-1178. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Monteleone I, Vavassori P, Biancone L, Monteleone G, Pallone F. Immunoregulation in the gut: success and failures in human disease. Gut. 2002;50 Suppl 3:III60-III64. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 14. | Liu Z, Colpaert S, D'Haens GR, Kasran A, de Boer M, Rutgeerts P, Geboes K, Ceuppens JL. Hyperexpression of CD40 ligand (CD154) in inflammatory bowel disease and its contribution to pathogenic cytokine production. J Immunol. 1999;163:4049-4057. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Oppmann B, Lesley R, Blom B, Timans JC, Xu Y, Hunte B, Vega F, Yu N, Wang J, Singh K. Novel p19 protein engages IL-12p40 to form a cytokine, IL-23, with biological activities similar as well as distinct from IL-12. Immunity. 2000;13:715-725. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 16. | Monteleone G, Monteleone I, Fina D, Vavassori P, Del Vecchio Blanco G, Caruso R, Tersigni R, Alessandroni L, Biancone L, Naccari GC. Interleukin-21 enhances T-helper cell type I signaling and interferon-gamma production in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:687-694. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 17. | Neurath MF, Fuss I, Kelsall BL, Stüber E, Strober W. Antibodies to interleukin 12 abrogate established experimental colitis in mice. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1281-1290. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 18. | Morrissey PJ, Charrier K, Braddy S, Liggitt D, Watson JD. CD4+ T cells that express high levels of CD45RB induce wasting disease when transferred into congenic severe combined immunodeficient mice. Disease development is prevented by cotransfer of purified CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:237-244. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 19. | De Winter H, Cheroutre H, Kronenberg M. Mucosal immunity and inflammation. II. The yin and yang of T cells in intestinal inflammation: pathogenic and protective roles in a mouse colitis model. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G1317-G1321. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Aranda R, Sydora BC, McAllister PL, Binder SW, Yang HY, Targan SR, Kronenberg M. Analysis of intestinal lymphocytes in mouse colitis mediated by transfer of CD4+, CD45RBhigh T cells to SCID recipients. J Immunol. 1997;158:3464-3473. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Szabo SJ, Kim ST, Costa GL, Zhang X, Fathman CG, Glimcher LH. A novel transcription factor, T-bet, directs Th1 lineage commitment. Cell. 2000;100:655-669. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Strober W, Fuss IJ, Blumberg RS. The immunology of mucosal models of inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:495-549. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Neurath MF, Weigmann B, Finotto S, Glickman J, Nieuwenhuis E, Iijima H, Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Mudter J, Galle PR. The transcription factor T-bet regulates mucosal T cell activation in experimental colitis and Crohn's disease. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1129-1143. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Parrello T, Monteleone G, Cucchiara S, Monteleone I, Sebkova L, Doldo P, Luzza F, Pallone F. Up-regulation of the IL-12 receptor beta 2 chain in Crohn's disease. J Immunol. 2000;165:7234-7239. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Kontoyiannis D, Pasparakis M, Pizarro TT, Cominelli F, Kollias G. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity. 1999;10:387-398. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Bamias G, Martin C, Mishina M, Ross WG, Rivera-Nieves J, Marini M, Cominelli F. Proinflammatory effects of TH2 cytokines in a murine model of chronic small intestinal inflammation. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:654-666. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Blumberg RS, Strober W. Prospects for research in inflammatory bowel disease. JAMA. 2001;285:643-647. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 28. | Fuss IJ, Neurath M, Boirivant M, Klein JS, de la Motte C, Strong SA, Fiocchi C, Strober W. Disparate CD4+ lamina propria (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-gamma, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261-1270. [PubMed] |

| 29. | (LP) lymphokine secretion profiles in inflammatory bowel disease. Crohn's disease LP cells manifest increased secretion of IFN-γ, whereas ulcerative colitis LP cells manifest increased secretion of IL-5. J Immunol. 1996;157:1261-1270. |

| 30. | Bouma G, Strober W. The immunological and genetic basis of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:521-533. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 31. | Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Chiba C, Spiekermann GM, Tonegawa S, Nagler-Anderson C, Bhan AK. Cytokine imbalance and autoantibody production in T cell receptor-alpha mutant mice with inflammatory bowel disease. J Exp Med. 1996;183:847-856. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 32. | Iijima H, Takahashi I, Kishi D, Kim JK, Kawano S, Hori M, Kiyono H. Alteration of interleukin 4 production results in the inhibition of T helper type 2 cell-dominated inflammatory bowel disease in T cell receptor alpha chain-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1999;190:607-615. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 33. | Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Bhan AK. The critical role of interleukin 4 but not interferon gamma in the pathogenesis of colitis in T-cell receptor alpha mutant mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:320-326. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 34. | Boirivant M, Fuss IJ, Chu A, Strober W. Oxazolone colitis: A murine model of T helper cell type 2 colitis treatable with antibodies to interleukin 4. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1929-1939. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 35. | Heller F, Fuss IJ, Nieuwenhuis EE, Blumberg RS, Strober W. Oxazolone colitis, a Th2 colitis model resembling ulcerative colitis, is mediated by IL-13-producing NK-T cells. Immunity. 2002;17:629-638. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 36. | Fuss IJ, Heller F, Boirivant M, Leon F, Yoshida M, Fichtner-Feigl S, Yang Z, Exley M, Kitani A, Blumberg RS. Nonclassical CD1d-restricted NK T cells that produce IL-13 characterize an atypical Th2 response in ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1490-1497. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 37. | Kanai T, Totsuka T, Uraushihara K, Makita S, Nakamura T, Koganei K, Fukushima T, Akiba H, Yagita H, Okumura K. Blockade of B7-H1 suppresses the development of chronic intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2003;171:4156-4163. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 38. | Boirivant M, Marini M, Di Felice G, Pronio AM, Montesani C, Tersigni R, Strober W. Lamina propria T cells in Crohn's disease and other gastrointestinal inflammation show defective CD2 pathway-induced apoptosis. Gastroenterology. 1999;116:557-565. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 39. | Kollias G, Kontoyiannis D. Role of TNF/TNFR in autoimmunity: specific TNF receptor blockade may be advantageous to anti-TNF treatments. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:315-321. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 40. | Yamamoto M, Yoshizaki K, Kishimoto T, Ito H. IL-6 is required for the development of Th1 cell-mediated murine colitis. J Immunol. 2000;164:4878-4882. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 41. | Mudter J, Wirtz S, Galle PR, Neurath MF. A new model of chronic colitis in SCID mice induced by adoptive transfer of CD62L+ CD4+ T cells: insights into the regulatory role of interleukin-6 on apoptosis. Pathobiology. 2002;70:170-176. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 42. | Fuss IJ, Marth T, Neurath MF, Pearlstein GR, Jain A, Strober W. Anti-interleukin 12 treatment regulates apoptosis of Th1 T cells in experimental colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1078-1088. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 43. | van Deventer SJ. Anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in Crohn's disease: where are we now? Gut. 2002;51:362-363. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 44. | ten Hove T, van Montfrans C, Peppelenbosch MP, van Deventer SJ. Infliximab treatment induces apoptosis of lamina propria T lymphocytes in Crohn's disease. Gut. 2002;50:206-211. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 45. | Weiner HL. Induction and mechanism of action of transforming growth factor-beta-secreting Th3 regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:207-214. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 46. | Roncarolo MG, Bacchetta R, Bordignon C, Narula S, Levings MK. Type 1 T regulatory cells. Immunol Rev. 2001;182:68-79. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 47. | Groux H, O'Garra A, Bigler M, Rouleau M, Antonenko S, de Vries JE, Roncarolo MG. A CD4+ T-cell subset inhibits antigen-specific T-cell responses and prevents colitis. Nature. 1997;389:737-742. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 48. | Cong Y, Weaver CT, Lazenby A, Elson CO. Bacterial-reactive T regulatory cells inhibit pathogenic immune responses to the enteric flora. J Immunol. 2002;169:6112-6119. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 49. | Veltkamp C, Sartor RB, Giese T, Autschbach F, Kaden I, Veltkamp R, Rost D, Kallinowski B, Stremmel W. Regulatory CD4+CD25+ cells reverse imbalances in the T cell pool of bone marrow transplanted TGepsilon26 mice leading to the prevention of colitis. Gut. 2005;54:207-214. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 50. | Nakamura K, Kitani A, Strober W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 2001;194:629-644. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 51. | Read S, Malmström V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295-302. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 52. | Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Takahashi T, Ishida Y, Sakaguchi S. Stimulation of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells through GITR breaks immunological self-tolerance. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:135-142. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 53. | Mottet C, Uhlig HH, Powrie F. Cutting edge: cure of colitis by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2003;170:3939-3943. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 54. | Martin B, Banz A, Bienvenu B, Cordier C, Dautigny N, Bécourt C, Lucas B. Suppression of CD4+ T lymphocyte effector functions by CD4+CD25+ cells in vivo. J Immunol. 2004;172:3391-3398. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 55. | Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330-336. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 56. | Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, Benard A, Van Landeghen M, Buckner JH, Ziegler SF. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25- T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437-1443. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 57. | Das G, Augustine MM, Das J, Bottomly K, Ray P, Ray A. An important regulatory role for CD4+CD8 alpha alpha T cells in the intestinal epithelial layer in the prevention of inflammatory bowel disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:5324-5329. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 58. | Chen Y, Chou K, Fuchs E, Havran WL, Boismenu R. Protection of the intestinal mucosa by intraepithelial gamma delta T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14338-14343. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 59. | Tsuchiya T, Fukuda S, Hamada H, Nakamura A, Kohama Y, Ishikawa H, Tsujikawa K, Yamamoto H. Role of gamma delta T cells in the inflammatory response of experimental colitis mice. J Immunol. 2003;171:5507-5513. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 60. | Saubermann LJ, Beck P, De Jong YP, Pitman RS, Ryan MS, Kim HS, Exley M, Snapper S, Balk SP, Hagen SJ. Activation of natural killer T cells by alpha-galactosylceramide in the presence of CD1d provides protection against colitis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:119-128. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 61. | Ueno Y, Tanaka S, Sumii M, Miyake S, Tazuma S, Taniguchi M, Yamamura T, Chayama K. Single dose of OCH improves mucosal T helper type 1/T helper type 2 cytokine balance and prevents experimental colitis in the presence of valpha14 natural killer T cells in mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2005;11:35-41. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 62. | Mizoguchi A, Mizoguchi E, Bhan AK. Immune networks in animal models of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2003;9:246-259. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 63. | Allez M, Brimnes J, Dotan I, Mayer L. Expansion of CD8+ T cells with regulatory function after interaction with intestinal epithelial cells. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1516-1526. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 64. | Poussier P, Ning T, Banerjee D, Julius M. A unique subset of self-specific intraintestinal T cells maintains gut integrity. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1491-1497. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 66. | Stallmach A, Marth T, Weiss B, Wittig BM, Hombach A, Schmidt C, Neurath M, Zeitz M, Zeuzem S, Abken H. An interleukin 12 p40-IgG2b fusion protein abrogates T cell mediated inflammation: anti-inflammatory activity in Crohn's disease and experimental colitis in vivo. Gut. 2004;53:339-345. [PubMed] [DOI] |