修回日期: 2004-06-09

接受日期: 2004-06-17

在线出版日期: 2004-09-15

目的: 建立结肠慢传输运动实验动物模型, 探讨结肠组织Cajal间质细胞与结肠慢传输运动病理生理学变化的关系.

方法: 实验组小鼠皮下注射吗啡, 按吗啡给药时间分为: 实验组Ⅰ(吗啡每日2.5 mg/kg×30 d, n = 15)、实验组Ⅱ(吗啡每日2.5 mg/kg×45 d, n = 15); 设立相应的2个对照组(n = 15×2)小鼠皮下注射等量生理盐水. 日平均粪便重量及活性碳悬液推进试验比较实验组与对照组小鼠肠道传输功能; 免疫组化标记结肠组织Cajal间质细胞, 计算机图像分析系统分析各组小鼠结肠组织中Cajal细胞数量变化.

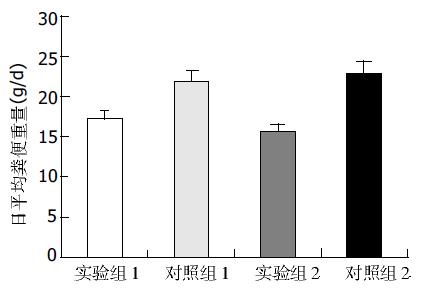

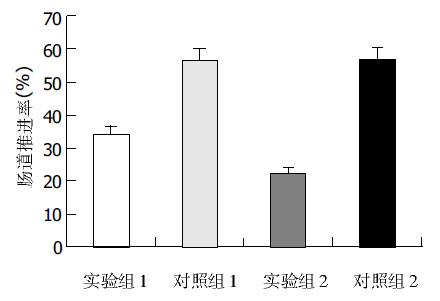

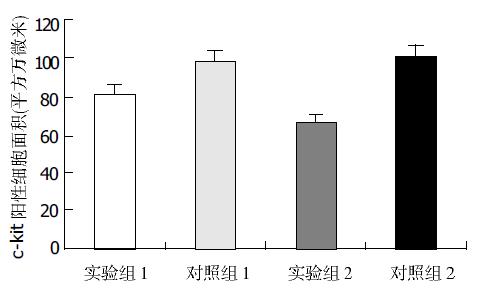

结果: 日平均粪便重量: 实验组Ⅰ为18.8±3.2 g, 对照组Ⅰ为20.6±1.8 g, 有显著差异(P <0.05); 实验组Ⅱ为16.8±2.0 g, 对照组Ⅱ为22.0±3.2 g, 有显著差异(P <0.01); 两实验组相比有显著差异(P <0.05), 两对照组无显著差异(P >0.05). 肠道推进率: 实验组Ⅰ为45.3±1.5%, 对照组Ⅰ为49.2±1.8%, 有显著差异(P <0.05); 实验组Ⅱ为40.6±1.3%, 对照组Ⅱ为50.6±3.0%, 有显著差异(P <0.01); 两实验组比较有显著差异(P <0.05), 两对照组无显著差异(P >0.05). 结肠c-kit+细胞面积: 实验组Ⅰ为81.3±7.9万mm2, 对照组Ⅰ为98.6±8.0万mm2, 有显著差异(P <0.01), 实验组Ⅱ为66.5±8.4万mm2, 对照组Ⅱ为100.9±10.0万mm2, 有显著差异(P <0.01), 两实验组比较有显著差异(P <0.01), 两对照组无显著差异(P >0.05).

结论: 吗啡诱导的小鼠结肠慢传输运动模型日平均粪便量、肠道推进率、结肠Cajal细胞数量较对照组均明显减少, 且减少的幅度与吗啡给药时间呈正相关.

引文著录: 林琳, 许海尘, 张红杰, 胡晔东, 林征, 赵志泉. 结肠慢传输运动小鼠Cajal间质细胞的改变. 世界华人消化杂志 2004; 12(9): 2107-2110

Revised: June 9, 2004

Accepted: June 17, 2004

Published online: September 15, 2004

AIM: To establish an animal model of slow transit constipation and to investigate the relationship between interstitial cell of Cajal in colon and the pathophysiological changes in the model of slow transit constipation.

METHODS: The mouse model was established by subcutaneous injection of morphine. According to period of morphine injected, the mice were divided into two groups: 2.5 mg/kg/per day ×30 d (n = 15) and 2.5 mg/kg/per day ×45 d (n = 15), and corresponding control groups were established by injecting the same dosage of 9 g/L sodium chloride solution. Fecal weight was recorded daily, and transit function of intestine was measured by activated charcoal suspension pushing test. The changes of interstitial cell of Cajal were observed by immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS: Fecal weight daily in test groupⅠwas less than control groupⅠ(18.8±3.2 g vs 20.6±1.8 g, P <0.05), and test groupⅡwas less than control group Ⅱ (16.8±2.0 g vs 22.0±3.2 g, P <0.01). It showed the significance of difference between the test groupⅠvs test groupⅡ(P <0.05), and no difference between two control groups (P >0.05). Intestinal transit rate in test group Ⅰwas lower than control groupⅠ(45.3±1.5% vs 49.2±1.8%, P <0.05), and test group Ⅱwas lower than control groupⅡ(40.6±1.3% vs 50.6±3.0%, P <0.01). There was a significant difference between test groupⅠvs test groupⅡ(P <0.05), and no difference between two control groups (P >0.05). Colon tissue c-kit+ cell's area in test groupⅠwas more decreased than that of control groupⅠ(81.3±7.9 ten thousand mm2vs 98.6±8.0 ten thousand mm2, P <0.01), and test group Ⅱvs control groupⅡwas 66.5±8.4 vs 100.9±10.0 ten thousand mm2 (P <0.01). There was a significant difference between the testⅠand testⅡ(P <0.01),and no difference in two control groups (P >0.05).

CONCLUSION: Daily fecal mass, intestinal transit ratio and the number of interstitial cells of Cajal are decreased in the mouse model of slow intestinal transit movement induced by morphine and have a positive correlation with period of morphine injected.

- Citation: Lin L, Xu HC, Zhang HJ, Hu YD, Lin Z, Zhao ZQ. Alterations of Cajal cell in colon of slow transit constipation mice. Shijie Huaren Xiaohua Zazhi 2004; 12(9): 2107-2110

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1009-3079/full/v12/i9/2107.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.11569/wcjd.v12.i9.2107

慢传输型便秘(slow transit constipation, STC)是由于结肠慢传输运动, 肠内容物通过缓慢而导致的便秘, 占功能性便秘患者的45.5%[1]. STC病因和机制不甚明了, 可能与肠神经系统、Cajal间质细胞(interstitial cells of Cajal, ICC)、神经递质等因素有关.目前国内外尚无较成熟的动物模型可供研究, 我们建立一种制作简单、可重复性强、基本符合STC临床及病理生理学特征的动物模型, 初步探讨ICC与STC的相关性.

ICR小鼠60只(购自江苏省试验动物中心, 雌雄各半, 每只20-25 g)无特定病原体环境饲育, 每天给予等量饲料及饮水.实验组Ⅰ小鼠(n = 15)盐酸吗啡(沈阳第一制药厂)sc 每日2.5 mg/kg×30 d, 实验组Ⅱ小鼠(n = 15)同样给予吗啡每日2.5 mg/kg×45 d; 设立相应的2个对照组(n = 15×2)小鼠, 给予等量生理盐水sc.

每日分别记录各组小鼠日平均粪便重量. 饲育30 d和45 d后, 分别将实验组和对照组小鼠禁食24 h, 经口灌入印度墨水0.5 mL, 30 min后颈椎脱臼法处死, 剖腹取出幽门到直肠末端全部肠道, 在无张力状态下测量肠道全长及墨汁在肠道的推进距离, 计算墨汁推进距离占肠道全长的百分比. 肠道推进率=墨汁推进距离/肠道全长×100%. 分别取每只小鼠远端结肠组织2-3处, 常规固定、包埋、切片、脱蜡至水. 放入EDTA缓冲液, 煮沸、保温、冷却; PBS洗涤、加入3%甲醇稀释的H2O2、室温孵育; PBS洗涤3次. 加入一抗(sc-168, 兔多克隆抗体, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, 200 mg/L; 稀释度1:500) 50 mL, 37 ℃孵育60 min. PBS洗涤5 min×3次. 加入生物素标记的二抗(羊抗兔抗体, 工作液浓度, 中山生物科技公司)50 mL, 室温孵育30 min. PBS洗涤5 min×3次. 加链霉菌抗生物素-过氧化物酶溶液50 mL, 室温孵育; PBS洗涤; 加DAB显色液100 mL, 显微镜下观察. 苏木素复染, 常规脱水、透明、封固. 细胞质染色呈棕色者判定为c-kit+细胞.

每张切片选择5个高倍镜视野(200×), 应用Leica Rχ250型图像分析系统进行定量灰度扫描, 以及Qwin软件分析并自动计算c-kit+细胞面积.

统计学处理 实验数据录入SPSS-11统计软件包, 应用方差分析, 所有数据以均数±标准差表示 P <0.05为有显著性差异.

所有小鼠在实验过程中未出现意外死亡. 日平均粪便重量, 实验组Ⅰ为18.8±3.2 g/d, 对照组Ⅰ为20.6±1.8g/d, 有显著差异(P <0.05); 实验组Ⅱ为16.8±2.0 g/d, 对照组Ⅱ为22.0±3.2 g/d, 有显著差异(P <0.01); 两实验组相比有显著差异(P <0.05), 两对照组相比无显著差异(P >0.05), (图1).

实验组Ⅰ为(45.3±1.5%), 对照组Ⅰ为(49.2±1.8%), 差异显著(P <0.05); 实验组Ⅱ为(40.6±1.3%), 对照组Ⅱ为(50.6±3.0%), 差异显著(P <0.01); 两实验组比较差异显著(P <0.05), 两对照组比较无显著差异(P >0.05), (图2).

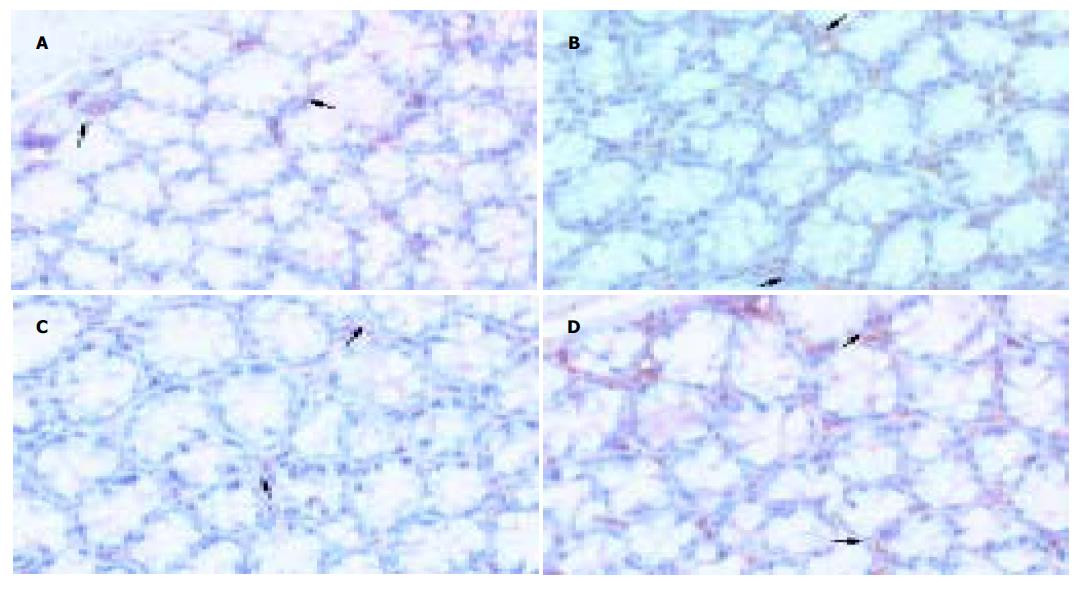

实验组Ⅰ为81.3±7.9万mm2, 对照组Ⅰ为98.6±8.0万mm2, 二者差异显著(P <0.01), 实验组Ⅱ为66.5±8.4万mm2, 对照组Ⅱ为100.9±10.0万mm2, 差异显著(P <0.01), 两实验组比较有显著差异(P <0.01), 两对照组相比无显著差异(P >0.05), (图3, 图4 A-D).

功能性便秘(functional constipation, FC, 即: 慢性便秘、特发性便秘)是临床常见的消化道病症. FC可分为结肠慢传输型(STC)、排出梗阻型和混合型, 其中以STC居多, 约占45.5%[1]. STC又称结肠无力型便秘, 主要临床特点为排便减少, 辅助检查证实有全胃肠或结肠通过时间延缓或结肠动力低下. 在病因和发病机制方面, 如肠神经元变性、ICC异常、平滑肌变性、胃肠激素和神经递质异常、遗传、心理因素等都可以作出部分解释[2-3], 但很难概括其确切病因及发病机制. 既往国内外便秘动物模型多采用泻剂造模, 实验动物易出现电解质紊乱、免疫力下降, 造模过程中死亡率较高, 可重复率低[4-5], 且造模成功的标准局限于动物粪便量及肠道动力学检测, 较少涉及胃肠道组织细胞学变化. 故建立一种基本符合STC病理生理特征的动物模型, 对进一步探索STC发病机制有重要意义. 我们在实验过程中全部小鼠未出现意外死亡, 较泻剂造模过程中死亡率明显降低.

阿片肽是肠神经系统中一种重要的抑制性神经递质, 主要通过m(mu), k(kappa), d(delta)阿片受体实现其作用[4], 他从中枢及外周水平影响胃肠运动, 对胃肠运动呈剂量依赖性抑制作用[6]. 吗啡镇痛治疗同时产生严重而且持久的便秘[7-8]; 文献[9]认为便秘患者直肠远端黏膜和黏膜下层阿片肽浓度增加. Kreek et al[10]提出, 阿片肽活性变化是STC的重要发病因素, 并用阿片受体拮抗剂治疗STC获得成功. 我们采用外源性阿片受体激动剂吗啡诱导小鼠胃肠动力改变[11-12], 结果实验组小鼠粪便重量减少, 肠道推进率减弱, 且与吗啡用药时间呈正相关, 符合STC的病理生理特征.

Cajal间质细胞( ICC)是消化道动力调控的基础-肠神经系统、平滑肌细胞和ICC三者之一, 他们共同形成胃肠道的运动模式. ICC以网络状结构分布于整个胃肠道, 其表达的原癌基因产物-酪氨酸蛋白激酶受体(c-Kit)是ICC的特异性标记, c-Kit免疫组化方法可对ICC进行特异性检测[19-23]. 进一步研究发现: 某些胃肠运动障碍性疾病的胃肠组织中出现ICC数量减少、形态及其网状结构改变, 如先天性巨结肠、慢性假性肠梗阻、先天性贲门失弛缓、糖尿病胃肠功能紊乱等[24-29]. 因此有人提出假设: ICC的缺失可能导致某些胃肠功能丧失[15]. 结肠组织中ICC不规则分布, 数量减少且体积显著缩小, 导致异常的不规则慢波, 平滑肌收缩运动减慢, 使结肠转运缓慢[30-31]; ICC是胃肠道的起搏细胞, 产生慢波和传导电兴奋, 介导神经递质的产生和作用, 在控制胃肠道运动中起重要作用[13-18]. 因此ICC的异常改变可能是STC的病因之一[25]. 我们用c-kit抗体特异性标记小鼠结肠ICC后, 计算机图像分析系统计算c-kit+细胞面积, 发现实验组小鼠结肠组织中ICC数量明显减少, 与对照组相比有显著差异, 且随着吗啡给药时间延长, 实验组小鼠结肠ICC数量进一步下降, 两实验组小鼠结肠ICC数量也有显著差异, 提示外源性吗啡与小鼠结肠ICC的变化存在相关性.

吗啡通过与中枢及外周阿片受体结合发挥抑制胃肠运动作用, 目前尚无证据表明ICC存在阿片受体. 我们用吗啡诱导的STC动物模型中小鼠粪便减少、肠道动力减退, 同时出现小鼠结肠ICC数量减少, 提示STC小鼠肠道存在ICC的异常改变, 这种改变与吗啡有无关系尚待研究. 综上所述, 我们初步探索的实验型STC动物模型方法简单、动物死亡率低、基本符合STC的病理生理特点, 为探讨STC病因及发病机制提供一个良好的载体.

| 2. | Tan-No K, Niijima F, Nakagawasai O, Sato T, Satoh S, Tadano T. Development of tolerance to the inhibitory effect of loperamide on gastrointestinal transit in mice. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2003;20:357-363. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 3. | Knowles CH, Martin JE. Slow transit constipation: a model of human gut dysmotility. Review of possible aetiologies. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2000;12:181-196. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 6. | Berstad A. Today's therapy of functional gastrointestinal disorders--does it help? Eur J Surg Suppl. 1998;92-97. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 7. | Vanegas G, Ripamonti C, Sbanotto A, De Conno F. Side effects of morphine administration in cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21:289-297. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 8. | Walsh TD, Rivera NI, Kaiko R. Oral morphine and respiratory function amongst hospice inpatients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:780-784. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 10. | Friedman JD, Dello Buono FA. Opioid antagonists in the treatment of opioid-induced constipation and pruritus. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35:85-91. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 11. | Ise Y, Katayama S, Hirano M, Aoki T, Narita M, Suzuki T. Effects of fluvoxamine on morphine-induced inhibition of gastrointestinal transit, antinociception and hyperlocomotion in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2001;299:29-32. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 12. | Niwa T, Nakao M, Hoshi S, Yamada K, Inagaki K, Nishida M, Nabeshima T. Effect of dietary fiber on morphine-induced constipation in rats. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2002;66:1233-1240. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 13. | Rumessen JJ, Vanderwinden JM. Interstitial cells in the musculature of the gastrointestinal tract: Cajal and beyond. Int Rev Cytol. 2003;229:115-208. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 15. | Ward SM, Sanders KM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the interstitial cell of Cajal: from bench to bedside. I. Functional development and plasticity of interstitial cells of Cajal networks. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G602-G611. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Huizinga JD. Physiology and pathophysiology of the interstitial cell of Cajal: from bench to bedside. II. Gastric motility: lessons from mutant mice on slow waves and innervation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1129-G1134. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Daniel EE. Physiology and pathophysiology of the interstitial cell of Cajal: from bench to bedside. III. Interaction of interstitial cells of Cajal with neuromediators: an interim assessment. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;281:G1329-G1332. [PubMed] |

| 19. | Vannucchi MG. Receptors in interstitial cells of Cajal: identification and possible physiological roles. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;47:325-335. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 20. | Filipoiu F, Lupu G, Tarta E, Indrei A, Paduraru D, Sorodoc L. [Cajal interstitial cells identification]. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi. 2002;106:142-146. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Faussone-Pellegrini MS, Thuneberg L. Guide to the identification of interstitial cells of Cajal. Microsc Res Tech. 1999;47:248-266. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 22. | Wester T, Eriksson L, Olsson Y, Olsen L. Interstitial cells of Cajal in the human fetal small bowel as shown by c-kit immunohistochemistry. Gut. 1999;44:65-71. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 23. | Streutker CJ, Huizinga JD, Campbell F, Ho J, Riddell RH. Loss of CD117 (c-kit)- and CD34-positive ICC and associated CD34-positive fibroblasts defines a subpopulation of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:228-235. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 24. | Taguchi T, Suita S, Masumoto K, Nada O. Universal distribution of c-kit-positive cells in different types of Hirschsprung's disease. Pediatr Surg Int. 2003;19:273-279. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 25. | Wedel T, Spiegler J, Soellner S, Roblick UJ, Schiedeck TH, Bruch HP, Krammer HJ. Enteric nerves and interstitial cells of Cajal are altered in patients with slow-transit constipation and megacolon. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1459-1467. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 26. | Hagger R, Finlayson C, Kahn F, De Oliveira R, Chimelli L, Kumar D. A deficiency of interstitial cells of Cajal in Chagasic megacolon. J Auton Nerv Syst. 2000;80:108-111. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 27. | Feldstein AE, Miller SM, El-Youssef M, Rodeberg D, Lindor NM, Burgart LJ, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Chronic intestinal pseudoobstruction associated with altered interstitial cells of cajal networks. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2003;36:492-497. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 29. | He CL, Soffer EE, Ferris CD, Walsh RM, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Loss of interstitial cells of cajal and inhibitory innervation in insulin-dependent diabetes. Gastroenterology. 2001;121:427-434. [PubMed] [DOI] |

| 30. | He CL, Burgart L, Wang L, Pemberton J, Young-Fadok T, Szurszewski J, Farrugia G. Decreased interstitial cell of cajal volume in patients with slow-transit constipation. Gastroenterology. 2000;118:14-21. [PubMed] [DOI] |