INTRODUCTION

Benign hepatic tumors, such as hepatocellular adenoma (HCA) and adenomatous hyperplasia (AH), result from a variety of neoplastic and regenerative proliferative processes. HCA is an uncommon benign tumor of the liver most frequently occurring in women with long-standing contraceptive steroid use[1-4,10,11]. It usually regresses after discontinuation of contraceptives[5,6]. HCA in men has usually been found in association with glycogen storage disease, diabetes, and the use of androgen and anabolic steroids[7,10,11]. HCA is usually solitary, but multiple adenomas have been described, ranging from two nodules to multiple or disseminated lesions of various size. The latter is termed hepatic adenomatosis[8-10]. Patients may present with a palpable mass over the right upper quadrant. Although most cases are asymptomatic and detected only incidentally, HCA may rupture and lead to life-threatening hemorrhage[12]. Malignant transformation of HCA is rare, but it may be very difficult to distinguish a benign tumor from a well-differentiated hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) clinically[10].

Edmondson first reported adenomatous hyperplasia (AH) of the liver in 1974. He defined it as a regenerative overgrowth with limited growth potential[13]. AH is the term most commonly used in Japan, while researchers in the United States and Europe call it a macroregenerative nodule (MRN). At the recommendation of the International Working Party Consensus Conference, the terminology for these dysplastic nodules has been standardized[10]. Based on characterization of cytological and architectural atypia, AH is generally classified as type I MRN (or ordinary AH) and type II MRN (or atypical AH)[14,30]. The lesions are usually associated with liver cirrhosis[14]. The size of AH varies from 5 mm to 10 mm in different series[10], but a huge AH lesion of 10 cm in diameter has been reported[29]. AH probably represents one type of malignant precursor[30]. However, the distinction of AH from well-differentiated HCC, particularly in samples obtained by needle biopsy, can be quite difficult, if not impossible[10]. Despite several cases reported in the literature, AH remains a poorly understood disease of unknown etiology.

We reported a case with infrequent presentation of both HCA and multiple AH lesions in HBV-related chronic liver disease.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Case report

A 30-year-old Asian man had been known to be a hepatitis B virus (HBV) carrier for many years. His younger brother had died of HBV-related HCC about 1 year ago. Therefore, he came to the outpatient department (OPD) of Mackay Memorial Hospital (a tertiary referral center) for evaluation of his liver condition. Nine years previously, he had undergone laparotomy at another hospital for a ruptured appendix. He had no history of smoking or alcohol consumption, and he denied use of any medications or exogenous hormones. His alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 40 U/L (normal: 5-30 U/L), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) was positive; “e” antigen of hepatitis B (HBeAg) was negative, and AFP 3.33 ng/ml (normal < 6.00 ng/ml). Abdominal sonography demonstrated (a) a space-occupying lesion consistent with HCC, (b) chronic liver disease (CLD), and (c) a gall bladder polyp without stone. The space-occupying hypoechoic lesion, measuring about 24 × 22 mm in size, was located in the right lobe of the liver (Figure 1). Because of the abnormal sonographic findings, he was admitted for further assessment and management.

Figure 1 A hypoechoic lesion in the right lobe of the liver, segment S6, 24 × 22 mm in diameter (asterisks).

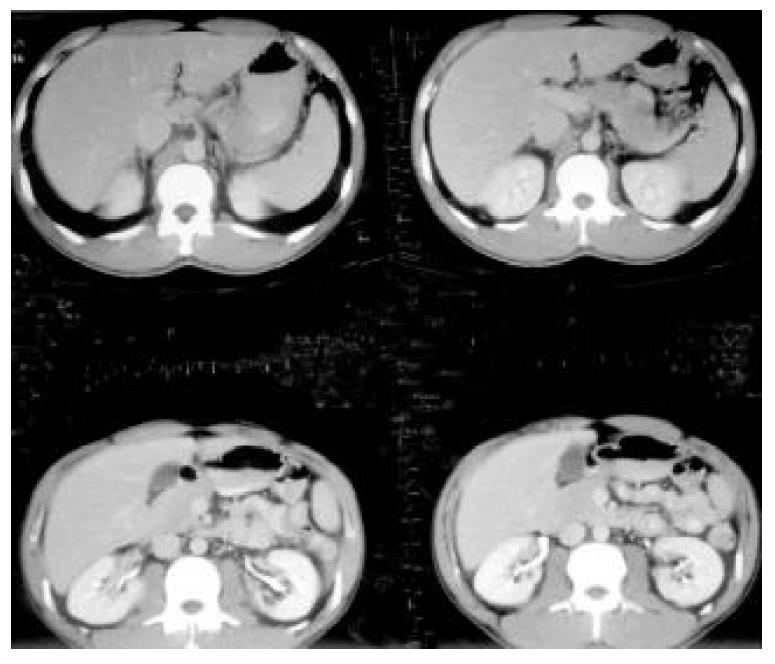

On physical examination, he had no hepatosplenomegaly or abdominal tenderness. In admission, not only the routine hemogram of blood cells and differential count, platelet count, but also prothrombin and activated partial thromboplastin time were normal. The urinalysis and stool for occult blood were negative findings. Biochemistry of blood glucose, protein, albumin, alkaline-phosphatase, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), ALT, total cholesterol, triglycerides, blood urea nitrogen, uric acid, creatinine, potassium, sodium, chloride, and CA19-9 were all normal. The total bilirubin was mildly elevated (1.4 mg/dL, normal range: 0.2-1.3 mg/dL), but the direct bilirubin was normal. The chest X-ray and electrocardiogram were unremarkable. No liver tumor was seen on computed tomography (CT) with or without contrast (Figure 2). On the 6th hospital day, he underwent hepatic angiography that revealed multiple tumor stains in the right lobe of the liver, strongly suggestive of HCC (Figure 3). Given the fact that this patient was hesitant to undergo operation and that there were multiple angiographic lesions, these tumors were embolized with 6 cubic centimetres lipiodol, 6 cubic centimetres lipodox, gelfoam pieces and cephazolin. The patient subsequently consented to surgery. Indocyanine green (ICG) was 3% (normal: 0%-10%).

Figure 2 No evidence of hepatocellular tumor seen on upper abdominal CT with contrast.

Figure 3 On angiography, there was an oval hypervascular lesion (black arrows) and multiple scattered tiny hypervascular spots in the right lobe of the liver (white arrows).

On the 17th hospital day, he underwent total right hepatic lobectomy and cholecystectomy. Grossly on the cut section, there was an easily identifiable, well-defined solitary nodule, 2 cm in the greatest dimension, darker than the surrounding hepatic tissue with a central stellate dark red appearance. The hepatic tissue elsewhere has several 2-4 mm, fairly well-defined dark gray spots. And three areas of subcapsular hemorrhage, the largest 1 cm in diameter, were noted. The surgical margins appeared to be free of tumor involvement.

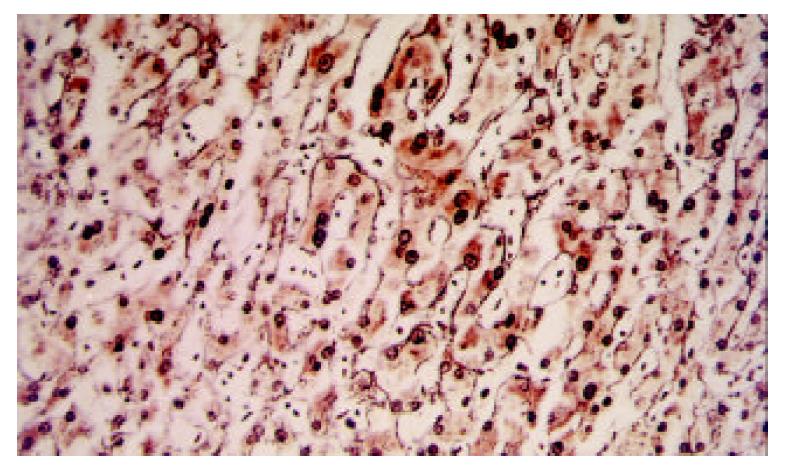

Microscopically, the main nodule was composed of hepatocytes much larger than the normal cells, with frequent nuclear dysplasia but no apparent increase of nucleus-to- cytoplasm ratio or mitoses. The arrangement of the hepatocytes in the nodule was disturbed (partially collapsed), which was thought to represent an ischemic-degenerative effect of embolization. However, there was not yet frank infarction except for a focal area in the stellate scar-like lesion in the center. Reticulin staining demonstrated a one-to-two layer arrangement with slight disarray, inconsistent with the appearance of HCC (Figure 4). No biliary ductules were found at the periphery of the stellate area. There was preservation of Kupffer’s cells. The lesion was fairly well demarcated from the surrounding normal liver tissue, but it lacked a capsule. The overall appearance indicated a liver cell adenoma post-embolization.

Figure 4 Slightly disarrayed hepatocytes with nuclear dyspla-sia were found.

Besides one-to-two layer reticulin stain, not consistent with HCC, was present. (Reticulin stain, × 250).

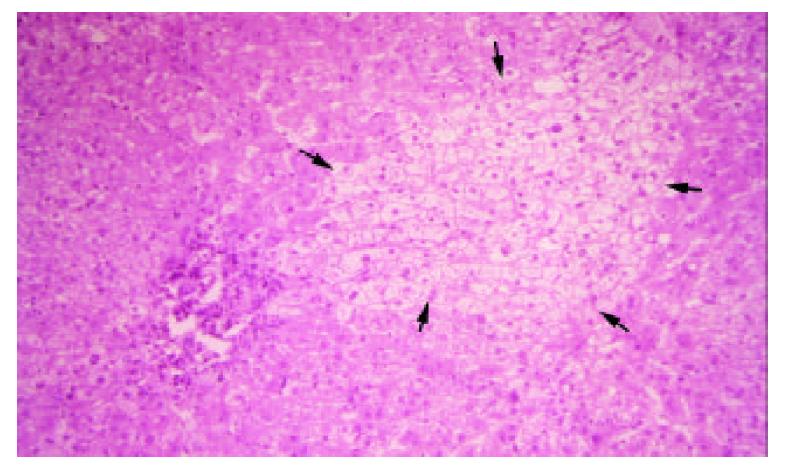

The small gray spots had slightly disarrayed hepatocytes with occasional nuclear dysplasia and clear changes in the cytoplasm, which were arranged in one-to-two-layer thin cords. They had preserved reticulin fibers, in contrast to HCC, and thus were consistent with AH (Figure 5). Excluding the aforementioned lesions, the remaining hepatic tissue was fairly normal except for focal areas with chronic inflammation in the portal triads with bridging fibrosis and possible early cirrhosis. However, post-embolization effect may be considered. The GB was found to have cholesterol polyps.

Figure 5 An oval-shape nodule (black arrows) which consisted of disarrayed hepatocytes with nuclear change and clear change in the cytoplasm was surrounded by normal liver tissue.

(H&E stain, × 125).

The patient recovered from surgery uneventfully. He was discharged and followed in the OPD. The other viral markers including HCV and HDV were negative by immunoassay.

DISCUSSION

In regions where HBV is hyper-epidemic, there is a corresponding increase in the incidence of HCC compared to areas with less HBV disease. HBV carriers are more likely than HBV-free individuals to develop HCC. Therefore, in Taiwan, China, with its high prevalence of HBV carriage and incidence of HCC, an HBV carrier presenting with a hepatic mass requires careful evaluation. Therefore, benign lesions must be precisely differentiated from malignant masses.

HCA is a rare benign tumor with a variable sonographic appearance. Cherqui et al[15] reported that, of 6 cases, 4 tumors were hyperechoic, 3 hypoechoic, and 1 isoechoic. Welch et al[16] reported that 4 of 13 tumors had mixed echogenicity and 1 was hypoechogenic. C.H. Hung et al[7] reported the appearance of 12 lesions, 1 with isoechogenicity, 4 with hypoechogenicity, 3 with hyperechogenicity, and the remaining with mixed echogenicity. The CT scan features of HCA are also very nonspecific. Mathieu et al[17] reported 22 cases with 27 tumors that were hyperdense and 5 with hypodense tumors on dynamic CT. Cherqui et al[15] described 3 lesions in 2 of 6 patients had a hyperdense area corresponding to recent hemorrhage, while the others didn’t. Welch et al[16] stated that, of 13 cases, 6 tumors were hypodense and 1 was hyperdense. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used, but it is not always helpful in distinguishing HCA from other liver tumor[11] Scintigraphy or radionuclide imaging provides a functional assessment of the liver but is helpless for anatomic imaging. Therefore, abdominal sonography, contrast-enhanced CT or MRI are all limited in their ability to discriminate HCA from HCC. However, they do provide helpful information on the size, number, and tumor location, particularly in relation to vascular structures and the biliary tract. It is very important to assess preoperatively.

Angiographic findings may also vary. Kerlin et al[1] demonstrated hypervascular tumors in all 15 patients examined, but 7 also had areas of hypovascularity. Welch et al[16] described 9 of 13 cases with hypervascular lesions that also contained small hypovascular area. As with the other imaging studies, the specificity of angiography is too low to provide a definitive diagnosis, but is helpful in assessing anatomy prior to resection. Some researchers have suggested using percutaneous fine-needle biopsy[18], but we are reluctant to do so. HCA is a hypervascular lesion, with a significant risk of hemorrhage if a large-caliber needle is used[19,21]. Second, if the lesion turns out to be malignant, there is a risk of tumor seeding along the needle track[19,20]. Third, a small sample obtained with a small-bore needle may not be adequate for a histological diagnosis[21]. Finally, lesions with malignant transformation within an adenoma could be missed, leading to a false-negative biopsy result. Therefore, we did not feel that percutaneous biopsy was appropriate in our patient.

In most reports, AH is considered to begin with small nodules in a cirrhotic liver, progressing to a larger nodule, and then rapidly transforming into a malignant lesion. Hence, AH is thought to be an early stage in hepatocarcinogenesis, especially when the AH is atypical[14,30]. While differentiation between malignancy and AH is clinically important, it is also quite difficult. Nomura et al[22] reported 4 cases, 2 of which were hypoechogenic and 3 of which had a hyperechoic focus in an area of hypoechoic change; all 4 lesions were missed on CT, and only 1 was detected at angiography. Again, some authors advise fine-needle biopsy. However, AH is a small liver tumor, usually less than 2 cm in diameter[10]. An adequate biopsy specimen should be at least 2.5 cm in diameter[23]. Given the relatively low chance of benefit, it is not worth the risk of biopsy in cases having small area of AH is suspected. Thus, as with HCA, imaging studies are helpful for screening but not for definitive diagnosis of AC, and biopsy is probably not helpful.

AH usually occurs in the presence of liver cirrhosis[10,24,25]. Nevertheless, Gindhart et al[26] reported a case of AH of the liver arising spontaneously in an 82-year-old woman without cirrhosis. Terada et al[27] described another case of AH in a patient with chronic active hepatitis. Theise et al[28] incidentally found a small HCC arising in AH in a patient with chronic hepatitis C infection but without cirrhosis. Furuya et al[25] reviewed 345 autopsy cases of chronic liver disease and found one case of AH in a noncirrhotic liver. In this case, aside from the HCA and AH, most of the liver tissue was normal, except for focal areas of early cirrhosis. The AH lesions all occurred in areas with normal liver tissue, not in conjunction with the focal cirrhosis. AH thus apparently can occur in CLD, not only in patients with cirrhosis. It may represent a malignant precursor in either condition.

In conclusion, this case confirms the difficulty noted in the literature of distinguishing HCA and AH from malignant hepatoma using clinical criteria alone, i.e., history, physical examination, imaging study or biopsy. Surgical intervention for diagnosis, therefore, is undoubtedly required. If that is not possible, very close follow up is recommended. Consideration of the diagnosis of AH should not be limited to patients with liver cirrhosis, since it may occur in CLD of varying etiology, such as HBV. Further research is needed to establish methods for early differentiation of small HCC and benign liver tumors. Until such methods are available, an aggressive, invasive approach is most likely necessary.