Published online Mar 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.609

Revised: July 15, 2002

Accepted: July 27, 2002

Published online: March 15, 2003

AIM: To report present state of iatrogenic drug-induced esophageal injury (DIEI) induced by medications in a private clinic.

METHODS: Iatrogenic drug-induced esophageal injury (DIEI) induced by medications has been more frequently reported. In a private clinic we encountered 36 cases of esophageal ulcerations complicating doxycycline therapy in a mainly younger Saudi population (median age 29 years).

RESULTS: The most frequent presenting symptoms were odynophagia, retrosternal burning pain and dysphagia (94%, 75% and 56%, respectively). The diagnosis was according to medical history and confirmed by endoscopy in all patients. Beside withdrawal of doxycycline, when feasible, all patients were treated with a proton-pump inhibitor (PPI) and a prokinetic. Thirty patients who reported to the clinic after treatment were improved within 1-7 (median 1.7) days.

CONCLUSION: Esophageal ulceration has to be suspected in younger patients with odynophagia, retrosternal burning pain and/or dysphagia during the treatment with doxycycline.

- Citation: Al-Mofarreh MA, Mofleh IAA. Esophageal ulceration complicating doxycycline therapy. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(3): 609-611

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i3/609.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.609

Three decades after the first report of drug-induced esophageal injury (DIEI) induced by potassium therapy[1], approximately 1000 cases of DIEI caused by almost 100 different drugs, have been reported in the world literature. Antibiotics have contributed to almost 50% and doxycycline alone to 27% of all cases[2].

The reported DIEI approximate incidence of 4/100000 is probably underestimated. The actual incidence is apparently much higher for increase of drugs prescription, and they are not all reported[2,3]. History has been considered sufficient for assuming a clinical diagnosis[4,5]. Retrosternal pain, sudden odynophagia with or without dysphagia is suspicious of the diagnosis[2]. History of medication, time of drug intake and amount of concurrent fluid ingested are important[6,7]. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is almost always abnormal and it has been considered as the method of choice to confirm DIEI[2]. The clinical course is usually uneventful and DIEI may heal after withdrawal of the offending drugs[5-8].

In a retrospective analysis of upper gastrointestinal (UGI)-endoscopies performed at Dr. Al Mofarreh’s Polyclinic over a period of 9 years, 36 patients who had doxycycline-induced esophageal ulcerations were included in this study. Another seven patients, who had typical symptoms, but had no endoscopy, no ulcer on endoscopy or the offending medication was unknown, were not included.

The patients were asked history of recent drug intake, the mode, timing of medication and the concurrent amount of fluid ingested.

Endoscopy was performed after a 12 hours fasting using Pentax EPM 3000, EG 2901 videoscope after a local anesthesia with 10% xylocain spray or 2% xylocain viscous (Astra, Sweden). Hard print photo documentation was performed in all patients with a color video printer (UP-5000 P, Sony). The number of ulcers, their size, depth and localization at the esophagus were documented.

Patients were treated with withdrawal of doxycycline, when feasible, along with proton-pump inhibitors (PPI) and prokinetics and were requested to report within seven days of management initiation to give feedback on their response of treatment.

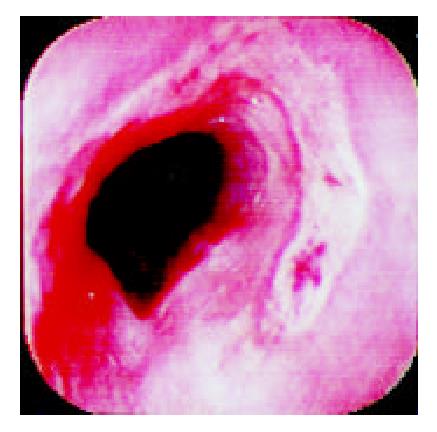

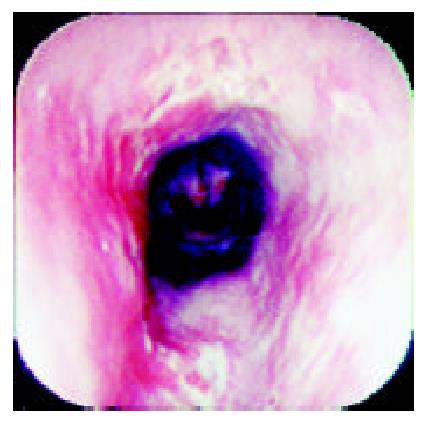

Over a period of nine years (from July 1992 to June 2001), 36 patients who complainted with sudden odynophagia (34 cases, 94%), retrosternal burning pain (27 cases, 75%) and/or dysphagia (20 cases, 56%) after ingestion of doxycycline capsules, underwent UGI-endoscopy and were found to have esophageal ulcerations. Their age ranged from 12 to 72 (Median: 29) years old and 22 were males. Endoscopy was performed within an average of six days after the onset of symptoms. The median number of ulcers was two (range: 1-9) and one patient had multiple ulcers spread all over the esophagus. The ulcers were localized at the mid, upper and lower esophagus in 24, 6 and 5 patients, respectively. In one patient, the ulcers were scattered all over the esophagus. The ulcers were variable in size, shape and depth (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4). No bleeding or significant strictures were encountered in these patients and none of the patients had a pre-existing esophageal disorder. Along with withdrawal of doxycycline when feasible, all patients were treated with PPI and prokinetics. All thirty patients, who reported for follow up,were improved within 1-7 (Median 1.7) days including three patients continued on doxycycline to treat brucellosis.

Approximately 100 types of drugs have been incriminated in the etiology of around 1000 cases of DIEI. The precise mechanism is not well explained. However multiple factors, including the increasing age, decreased esophageal peristalsis and external compression are predisposing to DIEI[2]. Furthermore, drugs that have a large size and sticky surface are retained longer in the esophagus[2,7,9]. A clinical and experimental study has shown that doxycycline capsules remain three times longer in the esophagus than doxycycline tablets[10].

Elderly patients are more prone to develop DIEI due to their altered esophageal motility and decreased saliva production. In addition, they more frequently suffer of cardiac disease, require more cardiovascular medication and remain longer in a recumbent position[7,11,12]. In younger patients, DIEI is mainly caused by antibiotics[2,5,6]. In our study, majority of patients were young and the only incriminated drug was doxycycline. All patients took doxycycline capsules and shared the same risk factor of taking the medication at bed time with a little amount of fluid. None of these patients suffered from a cardiac or a pre-existing esophageal disease.

The mechanism of esophageal mucosal injury induced by doxycycline capsules may be explained by their acidic effect, gelatinous sticky capsules, increased mucosal concentration and intracellular toxicity[2,13,14]. The presence of hiatus hernia in patients receiving indomethacin or doxycycline is associated with an increased risk of developing DIEI. The relative risk is 3.96[15]. The symptoms of DIEI, usually, manifest few hours up to ten days after exposure in form of chest pain, odynophagia and dysphagia, ranked according to their frequency[7]. In our series, odynophagia, retrostemal burning pain and dysphagia were the commonest symptoms and occurred in 94%, 80% and 54% of patients, respectively.

Although the typical history is sufficient to establish the diagnosis, endoscopy remains the method of choice for detecting DIEI[3]. Findings on endoscopic biopsies material are non specific[6,16].

Despite the absence of a significant stricture, dysphagia occurred more frequently in our population compared to other series[7].

The ulcer varied in size, depth and number. We have previously reported discrete, confluent, linear broad band-formed and butterfly-shaped ulcers partially covered with pseudomembranes. Ulcers were also noted on the opposite site with normal surrounding mucosa[6]. The majority (66%) of ulcers were at the mid-esophagus. The presence of mid-esophageal ulceration may raise the possibility of DIEI[5,6,17,18]. The presence of intact pills or their residues are also important clues for the diagnosis of DIEI[19].

In agreement with other authors, the main step of treatment in our patients was the withdrawal of the offending drug, however we feel doxycycline treatment could be continued when required with emphasis on patients education in regarding to timing of medication and required amount of fluid[6]. In addition, patients received a PPIs along with a prokinetics. The value of antacids, anti-secretory drug and PPIs remain questionable in patients without gastroesophageal reflux[5,7,10]. Apart from sucralfate, no data from the literature have suggested the benefit of acid suppression[2]. Patients who develop complications in form of hemorrhage or chronic stricture and with unsuccessful surgical intervention require endoscopic management[3,21].

In the majority of patient, DIEI symptoms resolved within one week (median time: 1.7 days). However, one patient went to the clinic with symptoms persisting over one month following a course of doxycycline and endoscopy revealed esophageal ulcerations. His symptoms were improved soon after initiation of treatment with a PPI and a prokinetic drug and ulcer healing was confirmed by endoscopy. Also the three patients continued with doxycycline to treat brucellosis improved. This observation supported continuation of doxycycline therapy when required and patients education was considered not only as a preventive, but also as a therapeutic measure.

Protracted courses up to six weeks and severe symptoms have also been reported[22]. Furthermore, severe non-typical symptoms in form of intractable hiccups have been described after the first dose of doxycycline inducing a lower esophageal ulcer at the gastric junction. The patients’ symptoms have been resolved with the medication of omeprazole and sucrealfate[23].

Doxycycline was the only offending drug in this study. A sudden onset of odynophagia, retrosternal pain and/or dysphagia in a healthy individual give a strong evidence of drug induced esophageal injury and necessitate a careful exploration of drug history. Endoscopy is important to determine the type, size, site and depth of injury. Discontinuation of the offending drug, when feasible, is the first step of management acid supressing agents and proleinetics may be proved helpful. In patients at risk, education and use of alternative medication are important preventive measures.

Edited by Xu XQ

| 1. | Pemberton J. Oesophageal obstruction and ulceration caused by oral potassium therapy. Br Heart J. 1970;32:267-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Kikendall JW. Pill esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1999;28:298-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jaspersen D. Drug-induced oesophageal disorders: pathogenesis, incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2000;22:237-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 113] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Ramírez Ramos A, Valladares G, Barreda Costa C. [Esophageal ulcers induced by doxycycline. Evaluation of 4 cases]. Acta Gastroenterol Latinoam. 1981;11:309-313. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bott S, Prakash C, McCallum RW. Medication-induced esophageal injury: survey of the literature. Am J Gastroenterol. 1987;82:758-763. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Al Mofarreh MA, Al Mofleh IA. Doxycline-induced esophageal ulcerations. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 1998;4:20-24. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Boyce HW. Drug-induced esophageal damage: diseases of medical progress. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;47:547-550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mason SJ, O'Meara TF. Drug-induced esophagitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981;3:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | 9 Hey H, Jørgensen F, Sørensen K, Hasselbalch H, Wamberg T. Oesophageal transit of six commonly used tablets and capsules. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285:1717-1719. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carlborg B, Densert O, Lindqvist C. Tetracycline induced esophageal ulcers. a clinical and experimental study. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:184-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bohane TD, Perrault J, Fowler RS. Oesophagitis and oesophageal obstruction from quinidine tablets in association with left atrial enlargement: a case report. Aust Paediatr J. 1978;14:191-192. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Boyce HW. Dysphagia after open heart surgery. Hosp Pract (Off Ed). 1985;20:40, 43, 47 passim. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Bonavina L, DeMeester TR, McChesney L, Schwizer W, Albertucci M, Bailey RT. Drug-induced esophageal strictures. Ann Surg. 1987;206:173-183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Giger M, Sonnenberg A, Brändli H, Singeisen M, Güller R, Blum AL. [Tetracycline ulcer of the oesophagus: clinical features and in-vitro studies (author's transl)]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1978;103:1038-1040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alvares JF, Kulkarni SG, Bhatia SJ, Desai SA, Dhawan PS. Prospective evaluation of medication-induced esophageal injury and its relation to esophageal function. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18:115-117. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Abraham SC, Cruz-Correa M, Lee LA, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Alendronate-associated esophageal injury: pathologic and endoscopic features. Mod Pathol. 1999;12:1152-1157. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kikendall JW, Friedman AC, Oyewole MA, Fleischer D, Johnson LF. Pill-induced esophageal injury. Case reports and review of the medical literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1983;28:174-182. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Castell DO. "Pill esophagitis"--the case of alendronate. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1058-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | O'Meara TF. A new endoscopic finding of tetracycline-induced esophageal ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1980;26:106-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | de Groen PC, Lubbe DF, Hirsch LJ, Daifotis A, Stephenson W, Freedholm D, Pryor-Tillotson S, Seleznick MJ, Pinkas H, Wang KK. Esophagitis associated with the use of alendronate. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1016-1021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 530] [Cited by in RCA: 480] [Article Influence: 16.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kikendall JW. Pill-induced esophageal injury. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:835-846. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Tankurt IE, Akbaylar H, Yenicerioglu Y, Simsek I, Gonen O. Severe, long-lasting symptoms from doxycycline-induced esophageal injury. Endoscopy. 1995;27:626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Tzianetas I, Habal F, Keystone JS. Short report: severe hiccups secondary to doxycycline-induced esophagitis during treatment of malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:203-204. [PubMed] |