Published online Oct 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2382

Revised: November 2, 2002

Accepted: November 9, 2002

Published online: October 15, 2003

Although the lung is the major site for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, gastrointestinal involvement can be present as part of multiorgan disease process or, less commenly, can be seen as primary gastrointestinal tuberculosis. In the cases where the culture is negative, it can be difficult to differantiate tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease based on both the clinical and histological features. When side effects of classic antimycobacteria are encountered, we can initially add ciprofloxacin to the treatment of tuberculosis. We reported a case of 19-yr-old patient, who was treated as Crohn’s disease and worsen. We began to tuberculosis treatment, and the patient improved clinically and histologically. The main point in this case is that widespread involvement of gastrointestinal tract can be brought about by non resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis even in immunocompetent patients.

- Citation: Settbas Y, Alper M, Akcan Y, Gurbuz Y, Oksuz S. Massive gastrointestinal tubercolsis in a young patient without immunosupression. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(10): 2382-2384

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i10/2382.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i10.2382

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the primary cause of tuberculosis, infects one third of world’s population and causes the most deaths per year of any infectious agents. It is found primarily in devoloping countries, where poor sanitation contributes to its spread. Although pulmonary manifestations predominate in most tuberculosis cases, gastrointestinal involvement may be present as a part of multiorgan disease process or, less commonly as primary gastrointestinal tuberculosis. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis is usually caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis but may also be caused by Mycobacterium bovis. Prior to AIDS epidemic, it was seen most commonly in immune competent persons with untreated advanced pulmonary disease[1]. Today, it is most commonly observed in association with immunosupression and, in one series, more than 40% of patients with gastrointestinal tuberculosis had AIDS[2]. Other groups at highest risk include those who abuse alcohol, injection drug users, those who take chronic steroids, elderly persons. Here, we described a case of gastrointestinal tuberculosis with diffuse involvement of esophagus, stomach, ileum and colon, who did not possess any known immunosuppressive state in his history (Diabetes mellitus, alcohol abuse, protein calori malabsorbtion, AIDS).

A 19 year old male patient presented to the outpatient department with complaints of dispepsia and nausea for two years. Recently, vomiting after meals made the patient fear of eating. He first recieved anti ulcer medication with the diagnosis of peptic ulcer in another center. Since his complaints continued, endoscopic and colonoscopic examinations were performed and several biopsies were obtained. A diagnosis of Crohn’s disease was made at the same center. Lansaprazol 30 mg, mesalazine (500 mg p.o. t.i.d), hydrocortisone 10 mg/kg/day were begun. Despite the treatment regimen, no response to mesalazine and hydrocortizone was seen and since his complaints increased, he was admitted to our center with abdominal pain, anorexia, nausea, fatigue, weigth loss (15 kg/6 month). There were no pathologic findings on his chest X-ray. Ultrasound examination of the abdomen revealed unremarkable findings, except some degree of cahexia and apathetic appereance. Laboratory data included hemoglobin 11.5 g/dL, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 10 mm/hr, alanin aminotransferase 30 U/L, aspartat aminotransferase 40 U/L, total protein 4.1 g/dL, albumin 2 g/dL white blood cell count 6600, platelet count 314000, HBsAg (-), AntiHBsAg (-), Anti-HCVAg (-), HIV (-) and PPD levels 7 mm. Physical examination did not find any abnormal findings. He had no history of any disease which practically can cause diabetes mellitus, alcoholism and renal insufficiency, which are associated with immunodefficiency.

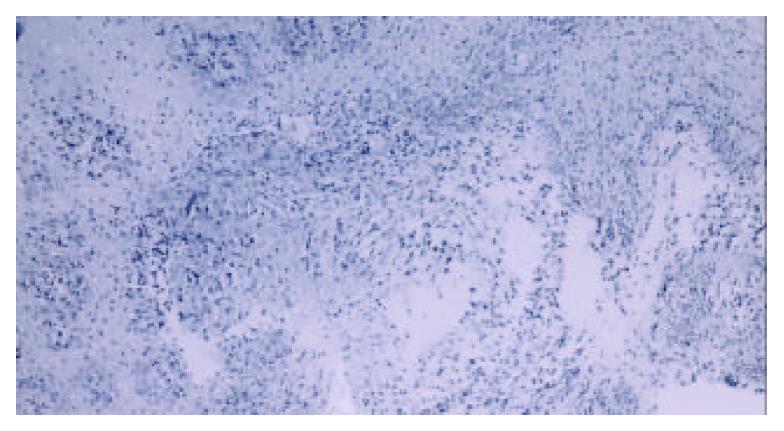

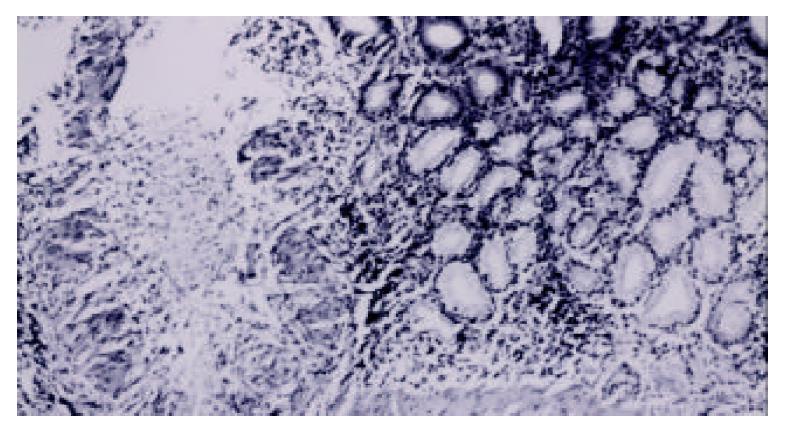

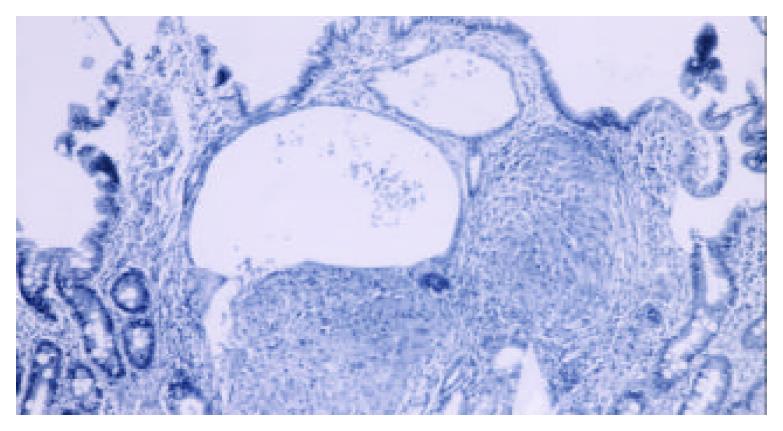

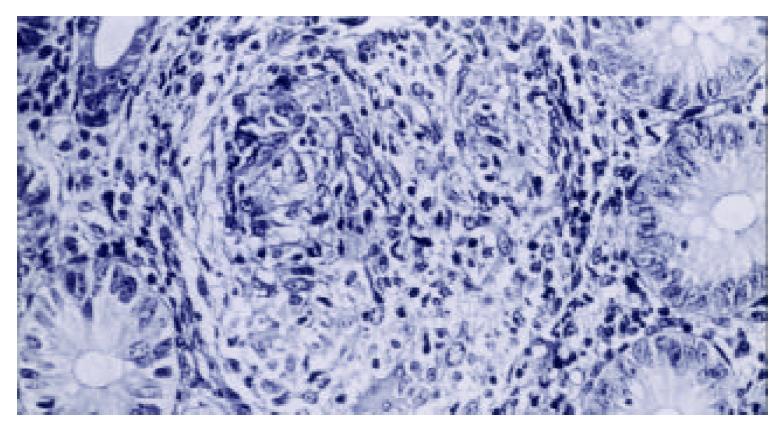

Endoscopy and colonoscopy were performed due to these complaints in our institution. Endoscopy revealed hyperemia with granulomatous lesions at the lower third of the esophagus. A granular appereance was seen along small curvature of the corpus. Antrum had extensive hyperdmia. Additionally granulomas were seen at bulbar and the second part of duodenum. Subsequently biopsies were obtained from all described areas. A histopathological examination revealed existance of granuloma in the esophagus, stomach and small intestine with caseous necrosis in the stomach (Figure 1, Figure 2, Figure 3). Although ileal biopsy revealed edematous lamina propria with increase of inflammatory cells, there was a granulation at the ileal biopsy which was done 3 months before the treatment of Crohn’s disease started at another center (Figure 4).

Under the light microscopy of these findings, gastrointestinal tuberculosis was concluded and treated with anti tuberculosis treatment of isoniazid 200 mg/day, rifampicin 450 mg/day, morfazinamid 1 g/day and ethambutol 500 mg/day. During the follow up of the first and second month, retrobulber neuritis and peripheral neuritis were seen as the side effects of ethambutol and isoniazid respectively. At the second month of the treatment, morfazinamid was also stopped. Ciproxin 500 mg two times a day with the combination of rifampicin 450 mg/day was given. A significant improvement in clinical situation of the patient was observed. He gained 25 kg during the theraphy and got 60 kg. The patient recieved anti tuberculosis treatment for 12 months. Check up endoscopy at the end of treatment revealed normal findings with no granulation and caseous necrosis.

The diagnosis of gastrointestinal tuberrculosis is always difficult. We must keep in mind the possibility of patients with abdominal pain, even without concomitent lung involvement[2,3]. Tuberculosis may affect any part of gastrointestinal tract, but it most commonly involves the terminal ileum and ileocaecal region, as Crohn’s disease did[4]. However it is rare to see the involvement of all parts of the gastrointestinal tract. Therefore, our case is intresting as almost the whole gastrointestinal tract has been affected.

The symptoms of gastrointestinal tuberculosis are nonspecific, and in the absence of pulmonary tuberculosis the diagnosis may be difficult. The most common symptom associated with gastrointestinal tuberculosis is abdominal pain. Other symptoms included diarrhea, fever, anorexia, weight loss, constipation, and hemorrhage[5].

A presumptive diagnosis can be made in the presence of known active pulmonary tuberculosis and based on the clinical and radiological findings in the bowel. Definitive diagnosis is essentially made by histology, with Ziehl-Neelsen staining for acid fast bacilli and culture. Colonoscopy and endoscopy of gastrointestinal system are the most useful nonoperative diagnostic tools. A combination of histology and culture can establish the diagnosis up to 80% of the patients. Altough more expensive PCR of biopsy specimens may facilitate diagnosis since it has higher sensitivity and specifity than routine culture, and results could be obtained in 48 hours instead of weeks[6]. The detection of anti-cord antibodies has recently been shown to facilitate the diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease[7]. However, the cases, which have negative results of culture and PCR can be seen and the diagnosis is achieved throuh histological assesment and response to antituberculosis treatment. Sometimes we could see the cases that had culture and PCR negative results were diagnosed histologically and recovered by tuberculosis tretment[8]. In our case, we established the diagnosis of tuberculosis by the presence of caseation and granulomatous lesions suggestive of tuberculosis, and essentially by the occurence of dramatic clinical improvement.

The lesions of gastrointestinal tuberculosis have clinically been divided into an acute ulcerative stage and chronic hypertrophic stage of the disease that is characterized by granulomas and extensive fibrosis. Ulcers are typically irregular with a necrotic base, which may extend to perforation. Fistulae and anorectal lesions may occur. These features are non-specific, and can also be seen in Crohn’s disease. In contrast, distinguishing histological features of granulomas in intestinal tuberculosis from Crohn’s disease have been described. Caseation, if present, strongly suggests tuberculosis. However central acute necrosis of granulomas may also be seen occasionally in Crohn’s disease.

Tuberculosis should always be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with obscure abdominal symptoms. Other entities, which are commonly misdiagnosed are Crohn’s disease, lymhoma, carcinoma, diverticular diseases, appendicities and other infections of gastrointestinal tract. Ulcers were more typically linear, and granulomas, when they were found had no caseation necrosis or organisms[9,10].

The prognosis of gastrointestinal tuberculosis depends primarily on the imuune status of the apropriate theraphy in a timely manner. In untreated HIV-infected patients, the disease progresses rapidly and is almost always fatal. If there is suspicious tuberculosis as histologically, treatment should beginn without waiting the result of the culture. The regimen of choice in most of the cases is isoniazid 3 to 5 mg/kg, rifampin 10 mg/kg, pyraazinamid 20-25 mg/kg and ethambutol 15 mg/kg all given once daily. In resistant cases ciprofloxacin can be used. However in our case because of the side affects of ethambutol and isoniazid, ciprofloxacin was given[11]. After a while of treatment histologic and clinical response was seen. It could be thought that ciprofloxacin could also be used in the treatment of Crohn’s disease[12]. Since the disease was worsen with the use of steroids, it should be thought that the effect of ciprofloxacin was against the tuberculosis.

This case report illustrates that the diagnosis of colonic tuberculosis requires a high index of suspicion. In cases where there is any doubt about the the diagnosis of Crohn’s disease, and even if the histology of colonic biopsies suggests Crohn’s disease, corticosteroids should be withheld due to disastrous results such as dissemination of tuberculosis. On the other hand, if the information not available to differentiate Crohn’s disease from tuberculosis, therapeutic trial of tuberculosis is justified because it whould not aggravate Crohn’s disease. In the cases of side affects of the drugs in tuberculosis, ciprofloxacin can be preferred in the combination with anti-mycobacterials which have no side affects. Tuberculosis of gastrointestinal tract can mostly be seen in immune compromised individuals such as HIV (+) individuals, alcoholic and chronic steroids users,but can also be seen in immunocompatible peoples. Although it’s mostly seen in the ileocecal region of gastrointestinal tract, it must be kept in mind that it can be widespreadly disseminated as in our case.

Edited by Xu XQ and Wang XL

| 1. | Pettengell KE, Larsen C, Garb M, Mayet FG, Simjee AE, Pirie D. Gastrointestinal tuberculosis in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Q J Med. 1990;74:303-308. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Shafer RW, Kim DS, Weiss JP, Quale JM. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Medicine (Baltimore). 1991;70:384-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 193] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pérez del Río MJ, Fresno Forcelledo M, Díaz Iglesias JM, Veiga González M, Alvarez Prida E, Ablanedo Ablanedo P, Herrero Zapatero A. [Intestinal tuberculosis, a difficult suspected diagnosis]. An Med Interna. 1999;16:469-472. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Brizi MG, Celi G, Scaldazza AV, Barbaro B. Diagnostic imaging of abdominal tuberculosis: gastrointestinal tract, peritoneum, lymph nodes. Rays. 1998;23:115-125. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Bouma BJ, Tytgat KM, Schipper HG, Kager PA. Be aware of abdominal tuberculosis. Neth J Med. 1997;51:119-122. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gan H, Ouyang Q, Bu H, Li S, Chen D, Li G, Yang X. Value of polymerase chain reaction assay in diagnosis of intestinal tuberculosis and differentiation from Crohn's disease. Chin Med J (Engl). 1995;108:215-220. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kashima K, Oka S, Tabata A, Yasuda K, Kitano A, Kobayashi K, Yano I. Detection of anti-cord factor antibodies in intestinal tuberculosis for its differential diagnosis from Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1995;40:2630-2634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Artru P, Lavergne-Slove A, Joly F, Bitoun A, Rambaud JC, Bouhnik Y. [Isolated jejunal tuberculosis mimicking Crohn disease. Diagnosis by push video-enteroscopy]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1999;23:1086-1089. [PubMed] |

| 9. | Jakubowski A, Elwood RK, Enarson DA. Clinical features of abdominal tuberculosis. J Infect Dis. 1988;158:687-692. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Tabrisky J, Lindstrom RR, Peters R, Lachman RS. Tuberculous enteritis. Review of a protean disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1975;63:49-57. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Berning SE. The role of fluoroquinolones in tuberculosis today. Drugs. 2001;61:9-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 91] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Peppercorn MA. Is there a role for antibiotics as primary therapy in Crohn's ileitis? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1993;17:235-237. [PubMed] |