Published online Jan 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i1.40

Revised: April 13, 2002

Accepted: April 23, 2002

Published online: January 15, 2003

AIM: To elucidate the relationship between lymph node sinuses with blood and lymphatic metastasis of gastric cancer.

METHODS: Routine autopsy was carried out in the randomly selected 102 patients (among them 100 patients died of various diseases, and 2 patients died of non-diseased reasons), their superficial lymph nodes locating in bilateral necks (include supraclavicle), axilla, inguina, thorax, and abdomen were sampled. Haematoxylin-Eosin staining was performed on 10% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded lymph node tissue sections (5 μm). The histological patterns of the lymph sinuses containing blood were observed under light microscope. The expression of CD31, a marker for endothelial cell, was detected both in blood and non-blood containing lymph node sinuses with the method of immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS: Among the 1322 lymph nodes sampled from the autopsies of 100 diseased cases, lymph node sinuses containing blood were found in 809 lymph nodes sampled from 91 cases, but couldn’t be seen in the lymph nodes sampled from the non-diseased cases. According to histology, we divided the blood containing lymph node sinuses into five categories: vascular-opening sinus, blood-deficient sinus, erythrophago-sinus, blood-abundant sinus, vascular-formative sinus. Immunohistochemical findings showed that the expression of CD31 was strongly positive in vascular-formative sinuses and some vascular-opening sinuses while it was faint in blood-deficient sinuses, erythrophago-sinuses and some vascular-opening sinuses. It was almost negative in blood-abundant sinus and non-blood containing sinus.

CONCLUSION: In the state of disease, the phenomenon of blood present in the lymph sinus is not uncommon. Blood could possibly enter into the lymph sinuses through the lymphaticovenous communications between the veins and the sinuses in the node. Lymph circulation and the blood circulation could communicate with each other in the lymph node sinuses. The skipping and distal lymphatic metastasis of gastric cancer may have some connection with the blood containing lymph node sinuses.

- Citation: Yin T, Ji XL, Shen MS. Relationship between lymph node sinuses with blood and lymphatic metastasis of gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(1): 40-43

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i1/40.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i1.40

It is well known that one of the most common behaviours of lymphatic metastasis of gastric cancer is their great tendency to produce skipping metastasis with the tumor emboli traversing the proximal lymph nodes encountered on their route or even bypassing them to form distant nodal metastasis (mainly at left supraclavicle). Skipping metastasis is a pecular kind of lymphatic metastasis. Until now, there have been few reports of this condition and its pathogenesis has not yet been clarified. Blood present in lymph node sinuses is a phenomenon that haven’t been deeply researched too. In the routine lymph node biopsy, erythrocytes in the lymph node sinuses could occasionally be seen. In the early literature, vascular transformation of lymph node sinus (VTS) and haemal lymph node sinus (HLs) have been reported. Their common feature is blood presenting in the lymph node sinus. Since lymph node sinus is also the place where the metastatic malignant tumor is located, we speculated there might be some inner relationships between the two phenomena. The purpose of this study is to find out the relationship between lymph node sinuses with blood and lymphatic metastasis of gastric cancer.

When routine autopsy was carried out in the randomly selected 102 patients died of different reasons, their superficial lymph nodes locating in the bilateral necks (include supraclavicle), axilla, inguina, thorax, and abdomen were sampled. Haematoxylin-Eosin staining was performed on 10% formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded 5 μm lymph node tissue sections. The histological patterns of the lymph node sinuses containing blood were observed under light microscope. The expression of CD31, a marker for endothelial cell, was detected both in blood and non-blood containing lymph node sinuses by immunohistochemistry.

The randomly selected 102 cases included 62 males and 38 females whose ages ranged from 2 months to 90 years (mean 45.08 years, median 57 years). Among the 102 cases, 100 patients died of various diseases, and 2 died of non-diseased reasons. The total number of the sampled lymph nodes was 1362 (1322 from the 100 patients died of various diseases and 40 from the 2 patients died of non-diseased reasons).

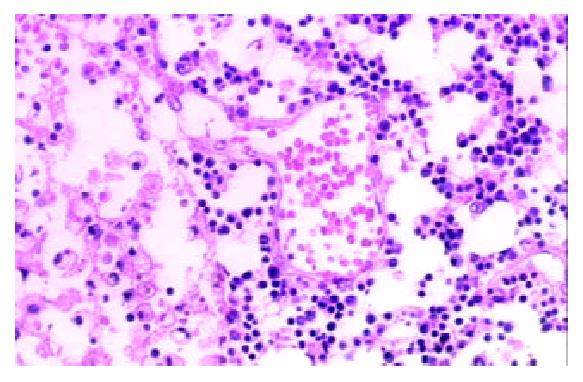

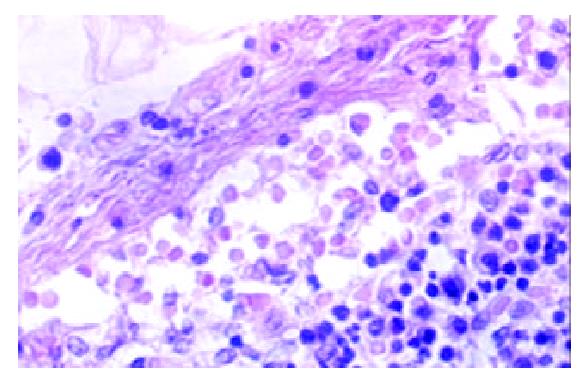

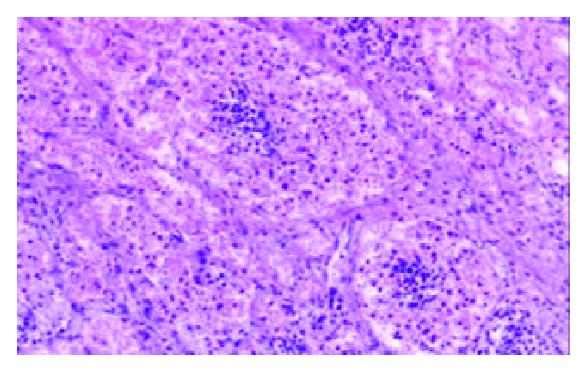

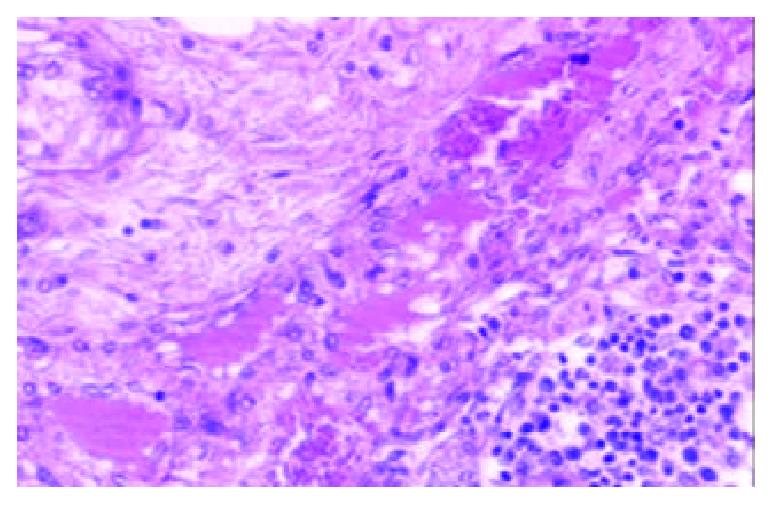

Among the 1322 lymph nodes sampled from the 100 autopsy diseased cases, blood containing lymph node sinuses were found in 809 lymph nodes sampled from 91 cases, whereas such sinuses couldn’t be seen in the lymph nodes sampled from the non-diseased cases. According to the histology, we divided the blood containing lymph node sinuses into five categories: vascular-opening sinus (in 338 lymph nodes from 68 cases), blood-deficient sinus (in 291 lymph nodes from 69 cases), erythrophago-sinus (in 344 lymph nodes from 69 cases), blood-abundant sinus (in 80 lymph nodes from 34 cases), and vascular-formative sinus (in 364 lymph nodes from 82 cases). In the vascular-opening sinus, venules and/or capillaries in the cortex and medulla extended or opened directly in the lymph node sinuses. Through the openning, blood could enter into the sinus (Figure 1). Blood-deficient sinus was defined as a small quantity of erythrocytes present in the lymph node sinuses (Figure 2). When erythrocytes in the sinuses were phagocytosed, erythrophago-sinus appeared. When the sinuses filled with blood, we called it blood-abundant sinus (Figure 3). Vascular-formative sinus was defined as vascular formation in the sinuses. We could see short to long sinuous vascular slits or vascular channels with round or oval contours lined by flat or plump endothelium. The channels were either empty or filled with an amorphous lymph-like materials and some red cells, occasionally they were markedly engorged with blood (Figure 4).

Immunohistochemical findings showed that the expression of CD31 was strongly positive in vascular-formative sinuses and some vascular-opening sinuses while it was faint in blood-deficient sinuses, erythrophago-sinuses and some vascular-opening sinuses. It was almost negative in blood-abundant sinuses and non-blood containing sinuses.

One of the most prominent features of the behaviour of carcinomas is their great tendency to produce secondary growths in regional lymph nodes. The early lymphatic metastasis of cancers almost invariably appear in the lymph nodes in the direction of normal lymph flow and the marginal sinus is the place where the metastatic growths are initially situated for the afferent lymphatics of lymph node enter the marginal sinus[1-7]. As for the spread of the tumor to the lymph nodes in the direction contrary to the normal lymph flow or the lymph nodes far from the primary carcinomas, what is called skipping metastasis, it has always been convinced to be the consequence of the cancerous occlusion of the principal lymphatics; the lymph flow is diverted or sometimes reversed, into collateral channels passing to neighbouring unaffected nodes. Skipping metastasis is a pecular kind of lymphatic metastasis. It was mostly recognised in the metastasis of gastric cancer to the supraclavicular lymph nodes which could be found as the earliest clinical symptom[8-11]. There have been some reports of this condition, but most were concerning with how to detect the metastasic foci and the relationship with clinical nodal stage[12,13]. Few mentioned the pathogenesis of skipping metastasis. The presence of previously unknown lymphatic tracts have been reported to explain the phenomenon[14]. The skipping of intact lymph nodes can also be explained by anatomically demonstrable intra- and perinodal short circuit connections. Apart from this, preexisting lymph node changes (silicosis, fibrosis) also play an important part[15].

Blood present in lymph node sinus is a phenomenon that haven’t been deeply researched. How the blood entering the sinus remains to be elucidated[16-29]. It’s well recognized that there are two circulations in the lymph node, one is the lymphatic circulation, the other is the blood circulation. They could communicate via the high endothelial venules (HEV) in the paracortex, but it is not certain whether there is some other pathway for the communication in human lymph node. In 1961, Pressman and Simon[24] devised experiments in dog to show that there were some other lymphatic-venous communications in lymph node. They inferred that the lymph node contained numerous lymphaticovenous communications between the lymph node sinuses and the veins. This claim has such far reaching implications that the work should be repeated both in the dog and in other species. When it come to the human lymph node, the studies of blood containing lymph node sinus were concentrated on the vascular transformation of sinuses (VTS) and Hemolymph nodes (HLs). The term VTS was first coined by Haferkamp et al[16] in 1971 for a distinctive benign vasoproliferative lesion of lymph node, which needed to be distinguished from Kaposi’s sarcoma(KS); venous obstruction was thought to be the underlying mechanism, but it was still controversial[30,31]. VTS is characterized by conversion of nodal sinuses into capillary-like channels, often accompanied by fibrosis[21,32]. Hemolymph nodes (HLs) were another target for the study of the communication between lymph circulation and blood circulation in the lymph node sinuses. HLs are unique lymph nodes, because their lymphatic sinuses contain numerous erythrocytes. In 1969, Turner DR[25] reported that blood entered the sinus through the communication between venule and sinuses, but it is still controversial[26-29]. From the above-mentioned phenomenons and the researches, we hypothesized that the two circulations in the lymph node could communicate in the lymph node sinus.

In this study, blood in the lymph node sinuses could be found frequently in the lymph nodes sampled from the patients died of disease. The histologic patterns of the changes were not limited to HLs and VTS. According to the histologic patterns, the blood containing lymph node sinuses were divided into 5 categories. Vascular-opening sinus was characterized by venules or capillaries stretching into the sinus with blood in the vascular releasing into the lymph node sinuses (Figure 1). So that, it testified the existence of lymph-venule communication in human lymph node sinuses. Through the vascular-opening sinus, blood could enter the lymph node sinuses directly. This finding was in accordance with Pressman and Simon[24]. Blood deficient sinus was possibly formed in the early period of the formation of sinuses containing blood, but the artifact factors should be excluded (Figure 2). The erythrophago-sinus was formed as a result of the phagocytosis of sinus-histocytes in the sinus. The red cells entered into the sinus were recognised as foreign bodies and engulfed by histocytes. When the pressure in venule increased for the stasis, plenty of red cells could rush into the sinus and the blood abundant sinus came into being due to the communication between lymph node sinus and venule (Figure 3). When the blood kept staying in the sinuses, an exceptional sinus containing blood-vascular formative sinus emerged. This kind of sinus was characterized by vascular formation in the lymph node sinus (Figure 4).

In order to clarify the features of endothelial cells of the lymph node sinus containing blood, monoclone antibody CD31 was used to label the endothelial cells by immunohistochemistry[32-35]. The expression of CD31 was different in the 5 blood contained sinuses. It was strongly positive in vascular-formative sinus and some vascular-opening sinus while it was weak in blood-deficient sinus, erythrophago-sinus and some vascular-opening sinus. It was almost negative in blood-abundant sinus and non-blood containing sinus. According to the expression of CD31 in different lymph node sinuses, we could speculated that the endothelial cells might experience the transformation from the lymph node sinus endothelial cells to the vascular endothelial cells. This course may have some connection with the blood in the sinuses[36]. The Prompt recognition of the ultrastructure and the mechanism of the phenomenon was needed.

Since lymph node sinus is the place where the metastatic malignant tumor is located and we found in this study that in the state of disease, there was the communication between lymph and blood circulations in the sinus, we speculated there might be some inner relationships between lymphatic skipping metastasis of gastric cancer and blood containing lymph node sinuses.

Early clinical observations let to the impressions that carcinomas frequently spread and grew in the lymphatic system, whereas tumors of mesenchymal origin spread more frequently by way of the blood stream[37]. In fact, this division is arbitrary because these two routes are actually interlinked and inseperable. Cancer cells may invade the lymphatics directly or gain access to them via blood vessels. Tumor cells can readily pass from blood to lymphatic communication via the interstitial spaces of lymph nodes and other tissues exist. When tumor cells entered the local blood circulation and was brought to the distant area, through the communications between the lymph circulation and the blood circulation in lymph node sinuses, they could enter the lymph node and stay in the lymph node sinuses where the foci of skipping metastatic tumors are formed. When the lymph circulation was obstructed, through the communication, blood metastasis of tumor cell could also be accelerated.

Although, lymph node sinus containing blood was only found in the cases died of disease in our study, it was not certain if this kind of lymph node could also be found in non-diseased cases, because such cases were limited. An in-depth study in a larger cohort of gastric cancer patients is needed to confirm whether lymph node sinus containing blood is also very common in such alived human lymph nodes, and their physiological and pathological significance in the skipping metastasis.

| 1. | del Regato JA. Pathways of metastatic spread of malignant tumors. Semin Oncol. 1977;4:33-38. [PubMed] |

| 2. | Scanlon EF. James Ewing lecture. The process of metastasis. Cancer. 1985;55:1163-1166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wittekind C. [Principles of lymphogenic and hematogenous metastasis and metastasis classification]. Zentralbl Chir. 1996;121:435-441. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hermanek P. [Lymph nodes and malignant tumors]. Zentralbl Chir. 2000;125:790-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Passlick B, Pantel K. Detection and relevance of immunohistochemically identifiable tumor cells in lymph nodes. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;157:29-37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kawaguchi T. [Pathological features of lymph node metastasis. 2) From morphological aspects]. Nihon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2001;102:440-444. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Gendreau KM, Whalen GF. What can we learn from the phenomenon of preferential lymph node metastasis in carcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 1999;70:199-204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Maruyama K, Gunvén P, Okabayashi K, Sasako M, Kinoshita T. Lymph node metastases of gastric cancer. General pattern in 1931 patients. Ann Surg. 1989;210:596-602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 324] [Cited by in RCA: 311] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Siewert JR, Sendler A. Potential and futility of sentinel node detection for gastric cancer. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2000;157:259-269. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Arai K, Iwasaki Y, Takahashi T. Clinicopathological analysis of early gastric cancer with solitary lymph node metastasis. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1435-1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kitagawa Y, Ohgami M, Fujii H, Mukai M, Kubota T, Ando N, Watanabe M, Otani Y, Ozawa S, Hasegawa H. Laparoscopic detection of sentinel lymph nodes in gastrointestinal cancer: a novel and minimally invasive approach. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:86S-89S. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Ichikura T, Furuya Y, Tomimatsu S, Okusa Y, Ogawa T, Mukoda K, Mochizuki H, Tamakuma S. Relationship between nodal stage and the number of dissected perigastric nodes in gastric cancer. Surg Today. 1998;28:879-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Aikou T, Higashi H, Natsugoe S, Hokita S, Baba M, Tako S. Can sentinel node navigation surgery reduce the extent of lymph node dissection in gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:90S-93S. |

| 14. | Yamamoto Y, Takahashi K, Yasuno M, Sakoma T, Mori T. Clinicopathological characteristics of skipping lymph node metastases in patients with colorectal cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 1998;28:378-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Junker K, Gumprich T, Müller KM. [Discontinuous lymph node metastases ("skipping") in malignant lung tumors]. Chirurg. 1997;68:596-59; discussion 600. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Aikou T, Higashi H, Natsugoe S, Hokita S, Baba M, Tako S. Can sentinel node navigation surgery reduce the extent of lymph node dissection in gastric cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8:90S-93S. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Steinmann G, Földi E, Földi M, Rácz P, Lennert K. Morphologic findings in lymph nodes after occlusion of their efferent lymphatic vessels and veins. Lab Invest. 1982;47:43-50. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Michael M, Koza V. Vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses--a diagnostic pitfall. Histopathologic and immunohistochemical study. Pathol Res Pract. 1989;185:441-444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Scherrer C, Maurer R. [Vascular sinus transformation of the lymph nodes. Morphological and immunohistochemical analysis of 6 cases]. Ann Pathol. 1985;5:231-238. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Lucke VM, Davies JD, Wood CM, Whitbread TJ. Plexiform vascularization of lymph nodes: an unusual but distinctive lymphadenopathy in cats. J Comp Pathol. 1987;97:109-119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chan JK, Warnke RA, Dorfman R. Vascular transformation of sinuses in lymph nodes. A study of its morphological spectrum and distinction from Kaposi's sarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1991;15:732-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ostrowski ML, Siddiqui T, Barnes RE, Howton MJ. Vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses. A process displaying a spectrum of histologic features. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1990;114:656-660. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Cook PD, Czerniak B, Chan JK, Mackay B, Ordóñez NG, Ayala AG, Rosai J. Nodular spindle-cell vascular transformation of lymph nodes. A benign process occurring predominantly in retroperitoneal lymph nodes draining carcinomas that can simulate Kaposi's sarcoma or metastatic tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19:1010-1020. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | PRESSMAN JJ, SIMON MB. Experimental evidence of direct communications between lymph nodes and veins. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1961;113:537-541. [PubMed] |

| 26. | Cerutti P, Marcaccini A, Guerrero F. A scanning and immunohistochemical study in bovine haemal node. Anat Histol Embryol. 1998;27:387-392. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hogg CM, Reid O, Scothorne RJ. Studies on hemolymph nodes. III. Renal lymph as a major source of erythrocytes in the renal hemolymph node of rats. J Anat. 1982;135:291-299. [PubMed] |

| 28. | Abu-Hijleh MF, Scothorne RJ. Studies on haemolymph nodes. IV. Comparison of the route of entry of carbon particles into parathymic nodes after intravenous and intraperitoneal injection. J Anat. 1996;188:565-573. [PubMed] |

| 29. | He YC, Shen LS, Yang CL, Fang WN, Li Hong. The distribution of lymphatic channels and red cells in the lymph nodes of rat blood. Jiepou Xuebao. 1991;22:239-241. |

| 30. | Samet A, Gilbey P, Talmon Y, Cohen H. Vascular transformation of lymph node sinuses. J Laryngol Otol. 2001;115:760-762. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jindal B, Vashishta RK, Bhasin DK. Vascular transformation of sinuses in lymph nodes associated with myelodysplastic syndrome--a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44:453-455. [PubMed] |

| 32. | Newman PJ. The role of PECAM-1 in vascular cell biology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;714:165-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | DeLisser HM, Christofidou-Solomidou M, Strieter RM, Burdick MD, Robinson CS, Wexler RS, Kerr JS, Garlanda C, Merwin JR, Madri JA. Involvement of endothelial PECAM-1/CD31 in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1997;151:671-677. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Newman PJ. The biology of PECAM-1. J Clin Invest. 1997;99:3-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 395] [Cited by in RCA: 372] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Watt SM, Gschmeissner SE, Bates PA. PECAM-1: its expression and function as a cell adhesion molecule on hemopoietic and endothelial cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 1995;17:229-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Fujiwara K, Masuda M, Osawa M, Kano Y, Katoh K. Is PECAM-1 a mechanoresponsive molecule. Cell Struct Funct. 2001;26:11-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Weiss L, Greep RO. Histology, Fourth Edition. USA: McGraw-Hill, Inc. 1977;523-543. |