Published online Aug 15, 2001. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.563

Revised: June 8, 2001

Accepted: June 15, 2001

Published online: August 15, 2001

The incidence of Barrett’s metaplasia (BM) as well as Barrett’s adenocarcinoma (BA) has been increasing in western populations. The prognosis of BA is worse because individuals present at a late stage. Attempts have been made to intervene at early stage using surveillance programmes, although proof of efficacy of endoscopic surveillance is lacking, particularly outside the specialist centres. The management of BM needs to be evidence-based as there is a lack clarity about how best to treat this condition. The role of proton pump inhibitors and antireflux surgery to control reflux symptoms is justified. Whether adequate control of gastroesophageal reflux early in the disease alters the natural history of Barrett’s change once it has developed and or prevents it in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease but with no Barrett’s change remains unanswered. There is much to be learned about BM. Thus there is great need for carefully designed large randomised controlled trials to address these issues in order to determine how best to manage patients with BM.

- Citation: Ishaq S, Jankowski JA. Barrett’s metaplasia: clinical implications. World J Gastroenterol 2001; 7(4): 563-565

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v7/i4/563.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v7.i4.563

The recent rise in the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in parallel with an increased incidence of Barrett’s metaplasia (BM) favours the theory that BM is a pre-cancerous lesion for adenocarcinoma. This BM is thought to occur as a result of prolonged and severe gastroesophageal reflux that can lead to chronic inflammation resulting in replacement of normal squamous epithelium in the distal oesophagus with specialised intestinal-type columnar epithelium containing goblet cells. Attempts have been made to treat acid reflux with medical treatment as well as anti-reflux surgery in the hope that it might prevent progression of BM. Surveillance strategies for established BM to detect early cancer have not been proven cost effective[1,2], although lesions identified during surveillance program have better prognosis. Despite extensive research, the natural history of BM is poorly understood. Many questions remain regarding the diagnosis of BM, its treatment, and the impact of surveillance strategies on early detection of cancer. It is important to realise the sheer scale of the problem as oesophagitis secondary to gastroesophageal reflux disease is one of most common conditions in the western world with up to 30% of adults complaining of heartburn at least once per month, a third of whom will develop oesophagitis. About 10% of patients with oesophagitis will progress to BM, of whom up to 5% will progress to cancer.

Using pooled data, the cancer risk in BM is about 1% (range 0.5%-2%)[3]. Proposed clinical risk factors for cancer progression including chronicity of symptoms, length of Barrett’s segment, gastroesophageal reflux and mucosal damage. For example gastroesophageal reflux symptoms are considered an independent risk predictor for cancer risk but may not discriminate low from high risk BM. Molecular changes in p53, p16, and cyclin D1 overexpression, decreased E-cadherin expression, and loss of heterozygosity of the adenomatosis polyposis coli (APC) gene have been detected[3]. These molecular changes have been evaluated in a clinical research setting but are not routinely used in clinical practice, although such genetic changes may become useful screening markers to monitor progression of BM and to identify individuals at risk of developing malignant transformation in the future. Thus, there is a pressing need for better understanding of BM and to develop strategies not only to prevent this pre-cancerous condition but also to identify high-risk individuals with this condition who are at risk of developing Barrett’s adenocarcinoma. This article discusses issues that concern clinicians in the management of BM including definition, diagnosis, screening and surveillance of BM, as well as management of uncomplicated BM.

BM may be defined as visible columnar-lined oesophagus of any length above the esophago-gastric junction (OGJ) confirmed on biopsies with the presence of specialised intestinal-type columnar epithelium containing goblet cells. However, there is considerable disagreement in defining BM. One technical problem in this regard is the precise identification of the OGJ. Suggested endoscopic criteria for identifying OGJ include the point of flaring of the stomach from the tubular oesophagus[4] and confluence of the proximal margin of longitudinal gastric folds[5]. One has to realise that this location point of flare can shift during breathing as well as peristaltic activity in the oesophagus and prolapse of the gastric folds into the oesophagus could further confuse the situation. Distinction between long and short Barrett’s segment is irrelevant as the tendency to develop high-grade dysplasia may be similar in short and long segment Barrett’s[6].

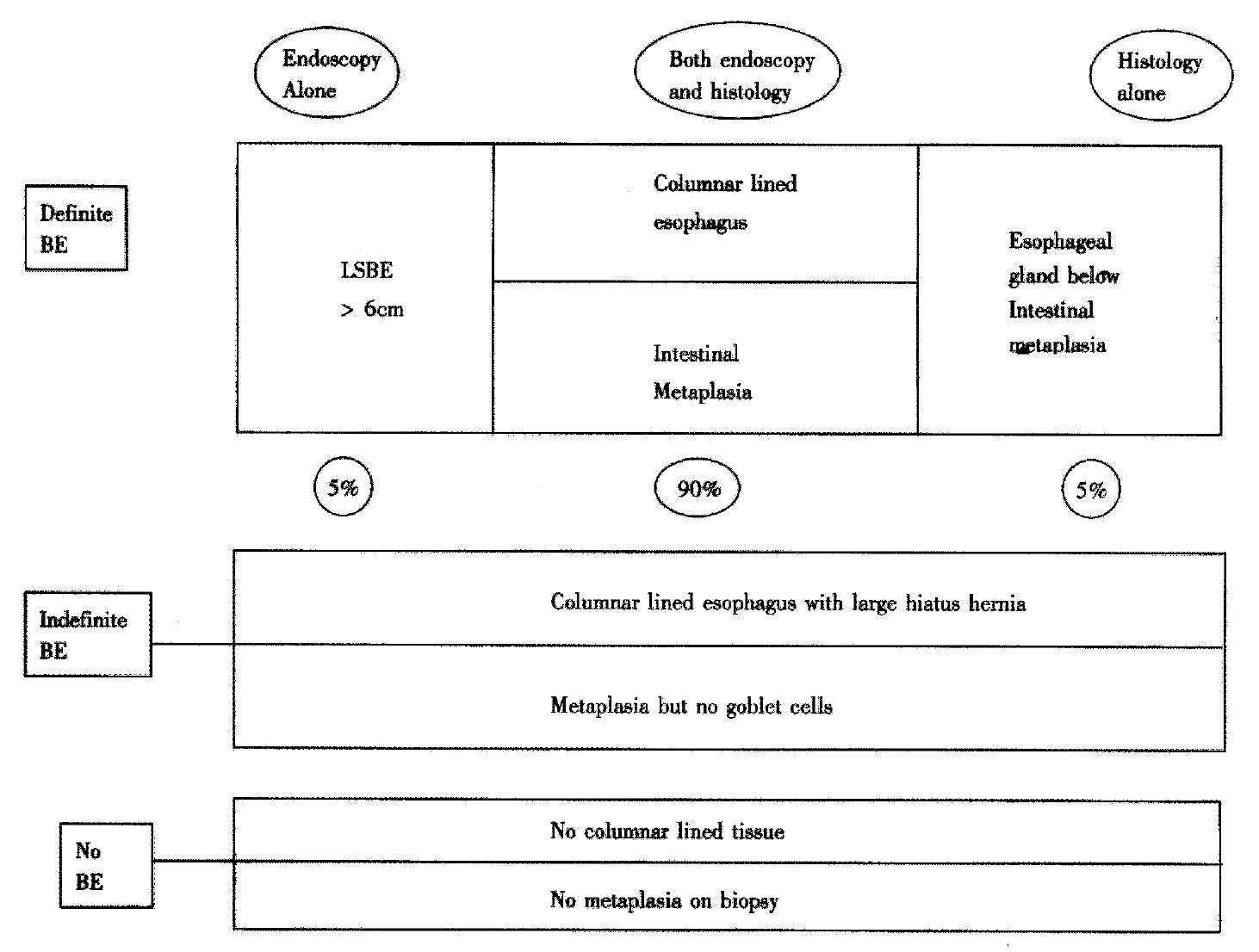

To avoid confusion endoscopists should avoid such terminology and instead describe only what they see i.e. if columnar-lined oesophagus is present or not and if present whether it is continuous or tongues and islands are observed. The histopathologist often finds it difficult to differentiate between intestinal metaplasia occurring in the distal oesophagus and in the cardia, and thus should avoid the term Barrett’s and instead report whether columnar epithelium is present and the presence or absence of intestinal metaplasia and identification of squamo-columnar junction. It is essential that precise site of biopsies with reference to OGJ should be documented to help the histopathologist make an accurate diagnosis. Thus the diagnosis of BM becomes clinicopathological integrating both endoscopic and histopathological information to increase diagnostic accuracy. Occasionally (1%-5% of cases), however, the pathologists see esophageal glands submerged under columnar-lined tissue corroborating the biopsy as being esophageal in origin (personal correspondence Prof N Shepherd, Gloucester Royal Hospital, UK) (Figure 1).

The true prevalence of BM in the general public is unknown. Reported lifetime risk in adult general populations in western countries is 1%[7] based on post-mortem studies. In addition, the incidence of new cases is about 0.5%-2.0%/year[3] and increasing[8]. It mainly occurs in white people, with a male predominance (male: female 2.3:1)[9]. Recently its prevalence has been shown to be rising all over the world, including in the Far East[10]. There is no significant relationship between smoking, alcohol consumption and high body mass index in the genesis of this metaplastic change.

It is not clear why only 10% of patients with oesophagitis progress to BM and why only a tiny fraction of these patients will go on to develop adenocarcinoma. In view of the low prevalence of BM in patients with gastroesophageal reflux as well as uncertainties regarding diagnosis and treatment, it is difficult to justify screening for Barrett’s in patients with gastroesophageal reflux, although patients aged > 45 with longstanding severe reflux symptoms (5-10 years) should have a one off screening endoscopy.Barrett’s adenocarcinoma develops through stages of increasing dysplasia (Sandic 1998). If this theory is correct, then surveillance endoscopies biopsies of BM should permit early cancer detection and reduce mortality from Barrett’s adenocarcinoma[11], as prognosis in early Barrett’s adenocarcinoma is more favourable as compared to advanced disease[12]. Attempts to identify tumours at early stage with surveillance programmes has not been cost effective in few studies[1,2]. Surveillance of BM with no dysplasia at 2.5 years has been recommended, although its usefulness has never been validated in a randomised study. Using the Markov model based on UK NHS cost per life saved if the surveillance programme is based on two yearly endoscopy, surveillance is comparable to other health disciplines in terms of cost per cancer detected and cost per life saved. It is fair to say that for an expense of this order we should first have some convincing evidence of effectiveness of surveillance programmes. Until results of such studies are available we face the dilemma of telling patients that they have a pre-cancerous condition with 5% life-time risk of cancer and that we could offer lifelong surveillance endoscopy programme that cannot guarantee to detect every cancer that may develop.

The symptoms of GORD, a presumed cause of BM, can be effectively eliminated with medical treatment or with anti-reflux surgery; however, regression of established BM does not occur with either intervention. On the other hand, many patients with BM will either have reduced or absent symptoms due to reduced sensation of Barrett’s epithelium. The role of PPI’s in BM is unclear. High dose PPI’s are still proposed regardless of symptoms by many who justify that such an approach may be necessary to achieve regression of BM[13]. Opponents of this approach advocate no treatment of asymptomatic BM and are less convinced that acid suppression prevents complications. Until there is more clarity in the scientific evidence, PPI’s remain an attractive treatment for the BM, especially if there is endoscopic evidence of esophagitis above the BM segment as is the case in about 40%-60% cases.

Competent fundoplication for BM has been advocated in patients with complications or intractable symptoms unresponsive to conservative medical treatment. If performed early, before the development of Barrett’s changes, fundoplication is slightly more effective than medical treatment to prevent this metaplastic change. The effect of this anti-reflux surgery on the natural history of BM once it has developed is less clear. Until we have more data to determine the role of anti-reflux surgery in the setting of BM or GORD, it would be sensible to perform these procedures once medical treatment fails or on patients fully informed of the choice. In addition, because there is a 0.1%-0.2% mortality rate for fundoplication surgery, this detracts from its efficacy. In particular, if there is an estimated 5% lifetime risk of cancer in BM, only half will die of the cancer because co-morbidity such as cardiac diseases will usually kill them. Secondly, no treatment is ever 100% effective in preventing cancer, so if 50% of individuals could be prevented from getting cancer only 1.25% of the 5% at risk population would benefit from surgery. Therefore for every 9 patients benefiting from long term advantages of surgery, 1 or perhaps even 2 would die prematurely from the surgery itself.

Because of the inability to effect regression of Barrett’s mucosa with medical or anti-reflux surgery, there has been renewed interest in the development of new modalities to eliminate this metaplastic change and hence reduce the cancer risk by destruction of Barrett’s mucosa by endoscopic ablation with thermal (Laser, Argon Plasma Coagulator), chemical (photodynamic) or mechanical (surgical ultrasound) in a reflux free environment to prevent further damage. These techniques have shown healing by squamous epithelium regeneration in 66%-100% patients[14], although nests of glandular epithelium may remain beneath the neo-squamous epithelium in up to 60% of patients that may progress to cancerous change. In view of this and high complication rates[14], many authors have debated the usefulness of these potentially hazardous therapies. Using NNT calculations, a reduction of absolute risk has not been established for any of these therapies. Efficacy of such treatment should thus be verified in controlled trials before their widespread use.

In spite of extensive research in this area it appears that we have more questions than answers. Our understanding of the natural history of BM is limited, as available data is not only insufficient but also either contradictory or subject to variable interpretation. Longstanding gastroesophageal reflux has been proposed to contribute towards BM. Whether adequate control of gastroesophageal reflux early in the disease alters the natural history of Barrett’s change once it has developed, or prevents it in patients with GORD, remains unanswered. To date, we simply cannot estimate or eliminate either the cancer risk or BM itself. On the basis of evidence available, it is difficult to promote or reject Barrett’s surveillance programmes on economic grounds alone. We must not forget that only 25% Barrett’s adenocarcinoma patients are known to have BM before they develop cancer and that 75% of cancer patients present for the first time with this disease without any prior knowledge of GORD or BM. Thus there is a pressing need for more work to be done, in large randomised controlled trials, to unravel these issues before we will be able to treat this condition effectively.

This paper was formulated at a time when the British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines were being written. We have tried to avoid any conflict of opinion and are grateful to Prof Hugh Barr, Prof Neil Shepherd, Department of Pathology of the Gloucester Royal Hospital (Gloucester, UK), Prof Tony Watson Department of Surgery of the Royal Free Hospital (London, UK) and Dr Paul Moayyedi of the Department of Gastroenterology General Infirmary (Leeds, UK).

Edited by Rampton DS and Ma JY

| 1. | Morales TG, Sampliner RE. Barrett's esophagus: update on screening, surveillance, and treatment. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:1411-1416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Macdonald CE, Wicks AC, Playford RJ. Final results from 10 year cohort of patients undergoing surveillance for Barrett's oesophagus: observational study. BMJ. 2000;321:1252-1255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 153] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Jankowski JA, Harrison RF, Perry I, Balkwill F, Tselepis C. Barrett's metaplasia. Lancet. 2000;356:2079-2085. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 227] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bozymski EM. Barrett's esophagus: endoscopic characteristics: Barrett's esophagus: Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. New York: Elsevier Science Publishing 1985; 113-120. |

| 5. | McClave SA, Boyce HW, Gottfried MR. Early diagnosis of columnar-lined esophagus: a new endoscopic diagnostic criterion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987;33:413-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rudolph RE, Vaughan TL, Storer BE, Haggitt RC, Rabinovitch PS, Levine DS, Reid BJ. Effect of segment length on risk for neoplastic progression in patients with Barrett esophagus. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:612-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in RCA: 179] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cameron AJ, Lomboy CT. Barrett's esophagus: age, prevalence, and extent of columnar epithelium. Gastroenterology. 1992;103:1241-1245. [PubMed] |

| 8. | Prach AT, MacDonald TA, Hopwood DA, Johnston DA. Increasing incidence of Barrett's oesophagus: education, enthusiasm, or epidemiology? Lancet. 1997;350:933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Sarr MG, Hamilton SR, Marrone GC, Cameron JL. Barrett's esophagus: its prevalence and association with adenocarcinoma in patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux. Am J Surg. 1985;149:187-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chen PH. Review: Barrett's oesophagus in Taiwan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;12:S19-S22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sampliner RE. Practice guidelines on the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett's esophagus. The Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1028-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 435] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Streitz JM, Andrews CW, Ellis FH. Endoscopic surveillance of Barrett's esophagus. Does it help? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:383-387; discussion 383-387. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Castell DO, Katzka DA. Importance of adequate acid suppression in the management of Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:1509-1510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Overholt BF, Panjehpour M, Haydek JM. Photodynamic therapy for Barrett's esophagus: follow-up in 100 patients. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:1-7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 364] [Cited by in RCA: 327] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |