INTRODUCTION

Hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinaemia are characters of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM). Their interaction further impairs the action and secretion of insulin in NIDDM[1]. With the aim of reducing the possibility of developing long-term various complications such as microvascular disorder or neuropathy[2], a good diet regimen and control of nutrient entry are broadly accepted as basic treatment for diabetes mellitus.

Acarbose, an alpha-D-glycosidase inhibitor, was first extracted from the culture broths of actinomycetes by Puls and his colleagues in the 1970s, and was applied in clinical studies for more than 10 years[3-5]. It reversibly inhibits alpha-glycosidases that exist in the brush-border of the small intestinal mucosa[6]. Its efficacy has been reported as a potent inhibitory effect on sucrose hydrolysis, but a weak effect on the maltose. For instance, in humans, even if high doses of 300 mg of acarbose are orally used, there is little effect on the absorption of maltose[7] and no obvious effects on body weight have been observed in most studies possibly due to its short effective duration. During daytime, blood glucose levels were hardly decreased although the postprandial blood glucose amplitudes were reduced, that also due to its short effective duration[8]. In addition, there is no interaction with the intestinal Na+/glucose- cotransporter[9], although an inhibitory effect on glucose absorption and an osmotic stimulus-mediating glucagon-like peptide-1 secretion has been reported[10,11].

Gymnemic acid (GA)[12], a mixture of triterpene glucuronides, which was found in the leaves of the Indian plant Gymnema sylvestre, not only inhibits glucose absorption in the small intestine[13], but also suppresses hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinaemia in an oral glucose tolerance test[14]. It is especially noteworthy that the body weight gain in fat rats is suppressed by GA treatment[15]. In an ordinary human diet, carbohydrates normally represent the quantitatively greatest part and are the primary source of energy. The typical diet contains far more starch than all other carbohydrates combined. More than 80% final products of intestinal carbohydrate digestion are glucose.

Maltose is a rather important product during starch hydrolysis. In this report, the combined effect of acarbose with GA on maltose absorption in the rat small intestines is reported. The mechanism and application in perspective are discussed.

METHODS

Animals

Male 8-9 weeks old Wistar rats (body weight 300 g ± 25g) obtained from Shimizu (Kyoto), were housed in an air-conditioned room at 22 °C ± 2 °C with a natural lighting schedule for 1 to 3 weeks until the experiment began. They were fed with a standard pellet diet (Oriental Yeast CO., Tokyo) and tap water. Care and treatment of the experimental animals conformed to Tottori University guidelines for the ethical treatment of laboratory animals.

Perfusion of small intestine in vivo

A modified technique as elaborated by Yoshioka[13] was used in the small intestine perfusion experiment. Animals that had fasted overnight with free access to water were anesthetized by an intraperitoneal injection of 50 mg/kg body weight sodium pentobarbital (Dainabot, Osaka). After a catheter was inserted in the trachea, the abdominal cavity was opened. The small intestine of 30 cm length from the 2 cm caudal ward of Treitz’s ligament was selected. Two L-shaped cannulae were inserted into each end of the intestine and connected with a peristaltic pump (SJ-1211H, Atto, Tokyo). After the abdominal cavity was closed, the intestinal loop was rinsed with Ringer’s solution (145.4 mmol/L NaCl, 5.4 mmol/L KCl, 1.8 mmol/L CaCl2 and 2.4 mmol/L NaHCO3) for 60 min. Each chemical that was dissolved in Ringer’s solution was continuously perfused through the intestine at a constant flow rate of 3 mL/min. The perfusing solution was adjusted to pH7.5-pH7.8 with NaOH and used at 37 °C.

The animals were randomly grouped and exposed to 20 mL 10 mmol/L maltose (Sigma, ST. Louis) with or without GA (extracted by ourselves from Gymnema sylvestre) and acarbose (Bayer, Osaka) by cyclic perfusion through the loops for 1 h (first perfusion), then 10 mmol/L maltose only was perfused for one hour again following an intestinal rinse with Ringer’s solution for 30 min (second perfusion). To compare the combined and individual effective duration, 5 groups were chosen, in which the rinse time between the two perfusions was prolonged from 30 min to 60 min, 120 min and 180 min respectively. The perfusates at the first perfusion in the 5 groups were as follows: ① control group,10 mmol/L maltose; ② acarbose group, 2 mmol/L acarbose + 10 mmol/L maltose; ③ GAa2 group, 1 g/L GA + 2 mmol/L acarbose + 10 mmol/L maltose; ④ GAa 0.2 group, 1 g/L GAa + 0.2 mmol/L acarbose + 10 mmol/L maltose; and ⑤ GA group, 1 g/L GA + 10 mmol/L maltose.

Measurement of maltose absorption and hydrolysis

The samples (20 μL) from perfusion fluid were taken every 15 min during 1 h perfusion period, which were kept at 0 °C until next step to prevent the possibility of further hydrolysis. The maltose hydrolyzed by over dosage of alpha-glucosidase (Funacoshi, Tokyo) and glucose in sample was measured with the glucose-B-test-kit (Wako, Osaka)[16], and by the percentages of absorption and hydrolysis of maltose in perfusate were calculated.

Recording of isometric contraction of the intestinal rings

To explain the combined effect of acarbose and GA, the effect of GA on contraction of the intestinal smooth muscle was investigated in vitro. Fasted animals were sacrificed by stunning and exsanguinations. The intestines at the same position as the perfusion experiments were removed, cleaned of adhering fat and connective tissues in the serous membrane, and cut into transverse rings of 1 cm wide. The rings were mounted on stainless steel hooks under 5 grams of resting tension and bathed in 25 mL organ bath at 37 °C in Locke’s solution containing (mmol/L) NaCl: 154, KCl: 5.6, CaCl2: 2.1, NaHCO3: 2.4 and Glucose: 5.6, which was saturated with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Tension was recorded isometrically using a force transducer (NEC Sanei, Tokyo) through its amplifier on an ink recorder (FBR-252A, TOA, Tokyo). Tissues were allowed to equilibrate at least 90 min before the experiments begun. The rings were treated with GA and the alterations of auto-rhythmic contraction were recorded.

GA extraction

Dry Gymnema sylvestre leaves were obtained from Okinawa (Japan), from which GA was extracted with water, ethanol and diethyl carbonate by a slightly modified version of Imoto’s method and freeze-dried into GA powder which was confirmed at 230 nm UV with a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Shimadzu SPD-6AV, Kyoto)[12].

Statistical and pharmacological analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with the U test of Mann-Whitney or ANOVA, which was indicated in the result when ANOVA was used, by StatView for a Macintosh computer. P < 0.05 was considered to be a significant difference.

The dose-response curves were analyzed by the least-squares fitting method using Cricket Graph for a Macintosh computer. The r (correlation coefficient) was tested with the limit table of r. If the value of r was under P < 0.05, the curve and function were accepted, from which the IC50 s (50% inhibitory concentrations) were calculated.

RESULTS

Dose-effect relationship and effective onset

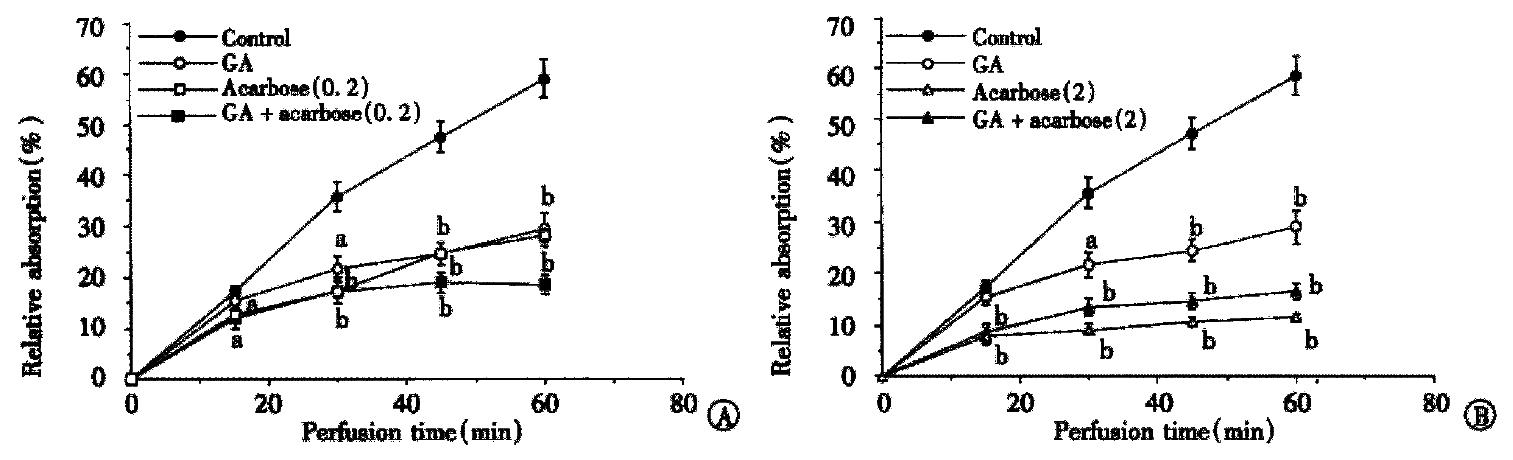

The inhibitory effects of GA and acarbose, or both of them, on 10 mmol/L maltose absorption obtained from the intestinal loop experiments in situ are illustrated in Figure 1 as a function of uptake time and compared at different doses of acarbose 0.2 mmol/L (Figure 1A) and 2 mmol/L (Figure 1B), respectively. Both agents inhibited maltose absorption significantly. The first point difference between the treated and control groups in maltose absorption was considered as the onset point of the inhibitory effect on maltose absorption. The duration from GA and/or acarbose perfused to that point was regarded as the onset time. The onset time was 30 min in the GA group and 15 min in both the acarbose and combining groups, in other words the longer onset time of GA was overcome by the combined. The inhibitory rates at 60 min were 50.7% ± 3.68% (1 g/L GA), 51.72% ± 2.21% (0.2 mmol/L acarbose) and 68.97% ± 2.71% (both of them), while at the high dose of acarbose they were increased to 80.68% ± 1.81% (2 mmol/L acarbose) and 72.27% ± 2.57% (both of them) indicating that the inhibitory effects were improved by the combination only in the lower doses during the first perfusion.

Figure 1 Inhibitory effect of GA and acarbose on maltose absorption.

The intestinal loops in situ were perfused with 10 mmol/L maltose in the presence or absence of GA (1 g/L) and acarbose (mmol/L). The absorption of maltose is shown as percentage of maltose contained in the beginning of perfusion. Each point is expressed as mean ± SD of 5-10 determinations. (aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01)

Time course of the inhibition

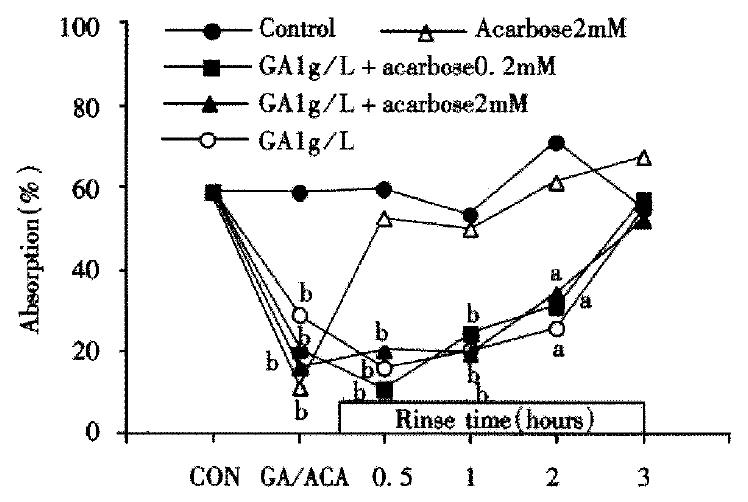

Time-effect curves of the GA and acarbose on absorption of maltose are shown in Figure 2. Even though the intestine was rinsed for 120 min, the altered maltose absorption remained at the inhibitory level in GA, GAa2 and GAa0.2 groups. In the case of acarbose only application, the absorption returned to almost normal after 30 min rinsing (P > 0.05 vs control). The present results suggest that the short effective duration of acarbose be overcome by the combination. The peak effect appeared during the first perfusion in GAa2 and acarbose (2 mmol/L) groups and the second perfusion following rinse for 30 min in GAa0.2 and GA groups. The altered absorption of maltose was recovered in each group to the control level after 180 min rinse with Ringer’s solution.

Figure 2 Alteration of maltose (10 mmol/L) absorption following application with GA and/or acarbose.

Each point shows the maltose absorption during 60 min perfusion of 10 mmol/L maltose following rise with Ringer’s solution after treatment of GA and/or acarbose (the second perfusion) except the points of “CON” or “GA/ACA” which shows the absorption during the first 1 hour perfusion with or without GA and acarbose (the first perfusion). The absorption of maltose is shown as percentage of maltose contained in the beginning of perfustion (aP < 0.05, bP < 0.01).

The IC50

The acarbose dose dependently inhibited the absorption of maltose with IC50s of 0.65 mmol/L, 0.27 mmol/L, 0.22 mmol/L and 0.28 mmol/L (r > or = 0.99) during 15 min, 30 min, 45 min and 60 min perfusion, respectively. The inhibitory effects were improved when combined with GA (P < 0.001 ANOVA). The IC50 s in an hour duration decreased to about 73% and 40% of acarbose with 0.1 g/L and 0.25 g/L GA, respectively. The inhibitory effects of GA (IC50 = 0.85g/L, r = 0.99) were also improved by lower doses of acarbose (P < 0.001 ANOVA) with IC50 s of 0.35 g/L (0.1 mmol/L acarbose) and 0.04 g/L (0.2 mmol/L acarbose) respectively.

Augment of GA and acarbose

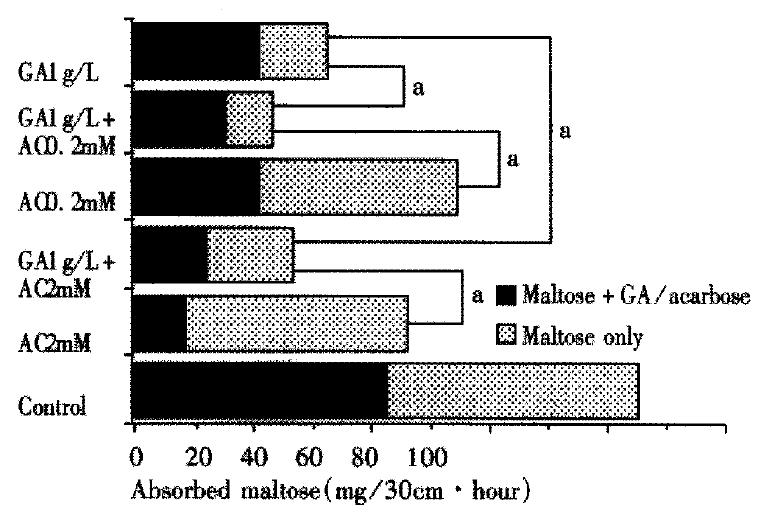

The amount of total maltose absorbed during the two perfusions is compared in Figure 3. The first perfusion was performed for 1 h by 10 mmol/L maltose containing GA and/or acarbose and the second was performed again for 1 h by 10 mmol/L maltose only, after rinsing for 30 min. The absorption of maltose during 1 h in control group was 42.2 mg and 43.0 mg in the first and second perfusions respectively, which had no significant difference. If the total absorbed maltose in control is taken as 100%, the relative maltose absorption was 64.2% ± 5.0% and 54.0% ± 7.3% in the 0.2 and 2 mmol/L acarbose groups respectively, which was further decreased to only 26.9% ± 2.9% and 31.0% ± 2.7% respectively by the combined 1 g/L GA. In GA (1g/L) group the relative maltose absorption was 38.1% ± 4.3% but still higher than that in combined groups (P < 0.05). These values implied that augmented inhibitory effects are highly revealed throughout effective duration in either combined group of GA and acarbose.

Figure 3 Maltose absorption during the two perfusions in the first 2.

5 hours. Maltose + GA/acarbose: first perfusion, 10 mmol/L maltose containing GA and/or acarbose was perfused for 1 hour. Maltose only: after first perfusion the intestinal loops were rinsed for 30 min, then 10 mmol/L maltose only was perfused for 1 hour again. The absorbed maltose is shown as the absorption in each perfusion. There was significant difference between each treated group versus control. (aP < 0.05, n = 5-10).

Modulation of the acarbose activity by GA

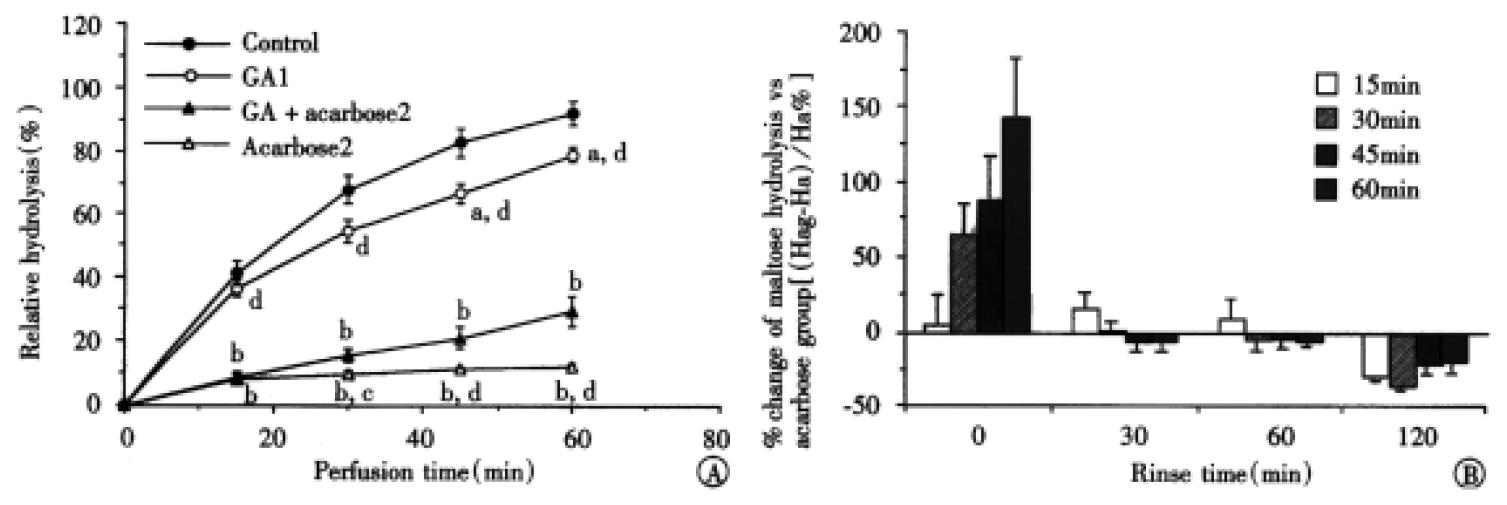

The percentages of maltose hydrolysis during perfusion maltose and acarbose with or without GA are shown in Figure 4A. It is noted that the inhibitory effect of 2 mmol/L acarbose on maltose hydrolysis was time-dependently decreased by combination with 1 g/L GA in the first perfusion. The hydrolysis of maltose in GAa2 group, which was similar to that in 0.2 mmol/L acarbose, was higher than that in 2 mmol/L acarbose group at 30 min (P < 0.05), 45 min and 60 min (P < 0. 01) except that at 15 min. On the contrary, the hydrolysis of maltose in the GAa2 group was lower than that in 2 mmol/L acarbose group (P < 0.05) in the second perfusion after the intestine was washed out for 120 min (Figure 4B). The hydrolyses at 15 min, 30 min, 45 min and 60 min were 15.77% ± 0.89%, 29.44% ± 0.18%, 45.18% ± 3.20% and 59.67% ± 5.86% in the former while 21.94% ± 1.36%, 45.38% ± 2.87%, 57.52% ± 1.69% and 73.14% ± 3.92% in the latter. No significant difference was observed in lower dosages of acarbose (0.2 mmol/L) with the presence or absence of GA.

Figure 4 The dual effects of GA (1 mg/mL) on the activity of acarbose during the first perfusion (A), maltose with GA and/or acarbose was presented in the perfusates.

Maltose contained in the fluid at perfusion starting point was taken as 100%. aP < 0.05 and bP < 0.01 vs control; cP < 0.05 and dP < 0.01 vs GAa2. (n = 6-10) and second perfusion (B), the intestinal loops were rinsed for 30 min to 120 min, then 10 mmol/L maltose only was perfused for 1 h again. Each bar shows the percentage change of maltose hydrolysis (Hc%) in GAa2 group versus 2 mmol/L acarbose group in different perfusing times, which was calculated by the following equation: Hc% = (Hag-Ha)/Ha × 100%, where Hag and Ha represent, respectively, the hydrolyzed maltose in GAa2 group and in 2 mmol/L acarbose group. Hydrolysis of maltose in the acarbose group is believed as 100% (n = 3-10). A diminished effect in the beginning and improved effect in the end were observed.

Correlation of GA’s inhibitory effects on absorption and mobility of the intestine

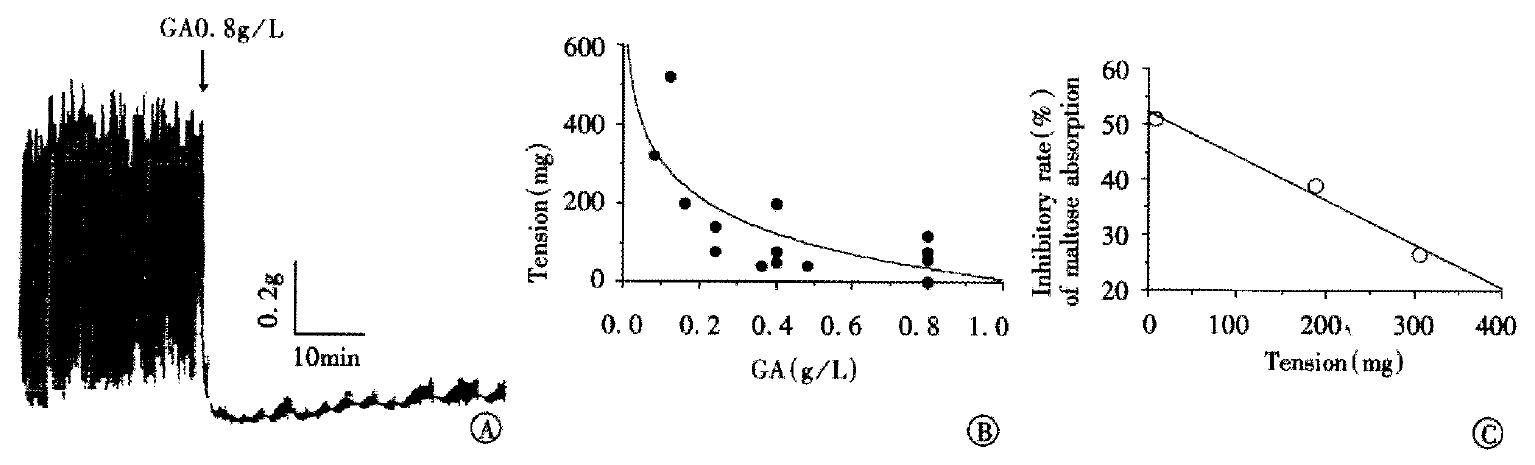

To explain mechanism of the combination, the effect of GA on auto-rhythmic contraction of the intestinal ring was recorded isometrically using a force transducer. Although the frequency of auto-rhythmic contraction was 17.2 ± 0.77 times per minute in the intestinal rings, and the tension induced by auto-rhythmic contraction was 1406.67 mg ± 565.33 mg under normal conditions, they were dose-dependently decreased when treated with GA (Figure 5A, B). The inhibitory effects of GA on the absorption of maltose and auto-rhythmic contractions of the ring in the small intestine had a good linear correlation (r = 0.98, Figure 5C).

Figure 5 The relationship of GA’s inhibitory effects on absorption of the maltose and on mobility of the intestinal ring.

A, an example of the inhibitory effect of GA (0.8 g/L) on the intestinal auto-rhythmic contraction. B, dose-dependently inhibitory effect of GA on amplitude of the small intestinal rings which is expressed as the tension induced by the auto-rhythmic contraction in the present different doses of GA. C, correlation of GA’s inhibitory effects on absorption of maltose and on tension of the intestinal ring. Each point comes from one dose of GA. The tension is calculated from the function of curve in the Figure 5B.

DISCUSSION

The combined effects of acarbose and GA are first reported in this paper. With the combination, inhibitory duration of acarbose was prolonged and onset time of GA was shortened, while the total inhibitory rate of maltose absorption was improved each other throughout their effective duration. Subsequently, a more effective reduction of postprandial hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinaemia could be expected by employing the combination in humans.

Acarbose is a pseudo-tetrasaccharide that is structurally similar to the typical oligosaccharides derived from starch digestion and can attach to the carbohydrate binding site of alpha-glycosidases in a competitive manner with a rank order of inhibitory potency of glucoamylase > sucrase > maltase > isomaltase. To alpha-amylase, acarbose has only a weak noncompetitive inhibitory effect[17]. In our experiment, the IC50 of acarbose for the 10 mmol/L (3.42 g/L) maltose absorption was 0.65 mmol/L during 15 min perfusion compared with a previous study of Krause et al[18], in which acarbose inhibits the absorption of maltose (1 g/L and 2 g/L) with IC50s of 36 mg/L (0.06 mmol/L) and 57 mg/L (0.09 mmol/L) respectively during 15 min in perfused loops. The IC50s and concentrations of maltose in the 3 points had a good semilog linear correlation (r = 0.94).

The inhibitory effects of GA on intestinal glucose absorption and oral glucose tolerance were first noticed in the 1980s[13,14], although there has been more than a century’s history of treating diabetes mellitus with the leaves of Gymnema sylvestre in India[19-24]. Recently, various effects of GA including decreased body weight[15], improved hyperinsulinaemia[14] and inhibited glucose-stimulated gastric inhibitory peptide secretion[25] have been published. In a previous study in our laboratory[13], GA inhibited intestinal glucose absorption consistent with the present results, but with a difference in time (5 mmol/L glucose). Rinsed with Ringer’s solution, the loops tended to recover their absorption of glucose. Those contrary results could be coming from the different effects of the unstirred layer and the tight junction on the absorption of maltose and lower concentration of glucose. In a recent study that we performed[26], GA inhibited the absorption of oleic acid and glucose (5 mmol/L) simultaneously with a time course same as the experiment of only 5 mmol/L glucose[13], which implies that the inhibitory effect of GA on the absorption of oleic acid has some relationship with the inhibitory effect of GA on glucose absorption.

Mechanism of the combination

The mechanisms for GA’s actions have been considered as participating in the glucose receptor[25], Na+/glucose cotransporter[13], ATPase[27] and insulin release[28]. In the present experiment, a new mechanism of GA’s action was suggested concerned with an influence of the precellular and paracellular barriers of absorption in the intestinal brush borders.

Intestinal absorption of solute requires that the compound cross two barriers, the unstirred layer as an aqueous diffusion barrier, and epithelium which consist of enterocytes and paracellular factors [29-34]. Disaccharides are absorbed at a faster rate than monosaccharides in vivo, but inversely in vitro for the absorption of disaccharides coupled with the membrane digestion. Oligomers invariably appear in monomeric form at the serosal side of the epithelial cell or in the blood stream[35]. The concentration of glucose hydrolyzed from maltose (10 mmol/L) in the microenvironment of enterocytes and the tight junction is nearly 200 mmol/L-300 mmol/L with membrane digestion[36], which is 10-15 times of that contained in the perfusate and is a power to drive absorption through paracellular pathway. If the tight junctions were narrowed or the membrane digestion was limited, the effect on the absorption of maltose would be more than that on the absorption of glucose.

“Membrane digestion” was defined by Ugolev and De-Laey[37] as that action of the cellular membranes on enzyme activities combined with the transport of their products of hydrolysis across membrane forms. The structural foundation of the model is presented as enterocytes projecting microvilli and the unstirred layer that is mainly formed by a glycocalyx entrapping water mixture with mucin from nearby goblet cells. Most of the disaccharidases produced by the enterocytes are binding with the membrane (under the unstirred layer) and a small amount of saliva and pancreatic amylase is in the glycocalyx. The maltose is hydrolyzed during it passes through the glycocalyx and enterocytes[38].

On the other hand, thickness of the unstirred layer (glycocalyx) largely depends on motility of the intestine, which becomes relatively thin when the intestine exhibits motility[29,37]. Suppressed by GA, the tension and intestinal auto-rhythmic contraction had un-negligible effects on unstirred layer not only, but also on the tight junction around the enterocytes. When the intestine relaxes, the paracellular pathways become narrow[36,39]. Consequently both hydrolysis and absorption could be inhibited by GA through pre-epithelium and epithelium barriers, in the latter containing transcellular (same as glucose) and paracellular factors (only for maltose or high concentration of glucose), that could be a main reason for the different time courses of GA on maltose and glucose.

It is another evidence altering the function of unstirred layer, that the activity of acarbose in the higher concentration (2 mmol/L) was decreased at the beginning and increased after rinsing by the combination with GA (Figure 4). The unstirred layer limits the diffusion of acarbose entering (at the beginning) and leaving (during rinse) the microenvironment nearest the membrane maltase resulting in the dual effects of GA on the activity of acarbose. It should be due to lower affinity[40] of acarbose with alpha-amylases, that the dual effects only appeared with higher concentration of acarbose. When the activity of alpha-amylases in the unstirred layer (glycocalyx) was inhibited, the glycocalyx digestion itself was decreased. With a combination of high concentration of acarbose and GA, the unstirred layer became thick enough to suppress the diffusion of acarbose. The glycocalyx is estimated to impede solute diffusion to the surface in a manner that is directly proportional to its solubility and inversely proportional to the square root of its molecular weight. The molecular weight of acarbose is nearly 2 times that of maltose, therefor in same condition the barrier of unstirred layer on acarbose is more effective than that on maltose. On the other hand, the solubility of GA (molecular weight about 800) was lower (about 10 g/L) than that of acarbose and maltose, which also is one of the reasons for GA’s longer onset time (30 min).

The merits of combination

Tolerability should be considered when a drug is administered to a patient. Acarbose has contained in the drug list of diabetic management either type 1 or type 2[5,40-46]. The most common adverse effect of acarbose is a gastrointestinal disturbance, which is induced by producing gas with fermentation of the unabsorbed carbohydrates in the bowel[17,43,47-50]. Acarbose has rarely been associated with systemic adverse effects, but in some case acute severe hepatotoxicity has been reported[3,51,52]. These adverse effects tend to increase with higher doses. GA not only improves the effect with a decrease in the IC50 of acarbose, but also inhibits the growth of anaerobia[53]. Bacterial overgrowth plays a role in the development of gastrointestinal symptoms[54], therefore the adverse effects of acarbose induced by fermentation are expected to be diminished by the combination of GA.

CONCLUSION

Acarbose inhibits maltose absorption through the inhibition of maltase under the unstirred layer and alpha-amylase in the unstirred layer. The latter is only involved at a higher dose (2 mmol/L) of acarbose. GA inhibits maltose absorption possibly by making the unstirred layer thicker and shutting the paracellular pathway, besides other reported mechanisms that are the same as glucose[13-15,25,27,28]. The effects of GA on maltose absorption and the combined effects of acarbose and GA are first reported in this paper. With the combination, the effective duration of acarbose is prolonged and the effective onset of GA is faster. Improvements in postprandialhyperglycemia, hyperinsulinaemiaandinsulin resistance, treatments of an overweight condition and diminishing of the adverse effects of acarbose in diabetic control by this combination are also in perspective.