INTRODUCTION

Molecular biology has made a tremendous impact on the diagnosis and treatment of liver diseases[1,2]. In particular, advances in molecular biology made possible the discovery of the virus that causes hepatitis C. In this review, we use hepatitis C as an example of the impact that molecular biology has made in t he area of liver disorders. We emphasize how our growing understanding of the he patitis C virus (HCV) has lead to the identification of targets for development of new treatments.

THE HEPATITS C VIRUS (HCV)

Basic molecular virology of HCV

Investigators at Chiron Corporation were the first to discover HCV and reported this in a landmark paper published in 1989[3]. The virus was identified by antibody screening of cDNA expression libraries made from DNA and RNA from the plasma of chimpanzees. These chimpanzees were inoculated with serum from human s with what was then called post-transfusion “non-A, non-B” hepatitis. The DNA expression library was screened with antibodies from sera of other patients with “non-A, non-B” hepatitis. This led to the isolation of clones that we re derived from portions of the viral genome and encoded fragments of viral poly peptides. Treatment with RNase and DNase showed that HCV was a positive-stranded RNA virus[3]. In an accompanying paper, the investigators who discover ed HCV and their collaborators showed that the vast majority of individuals with chronic “non-A, non-B hepatitis” had antibodies against the newly identifi ed viral polypeptides[4].

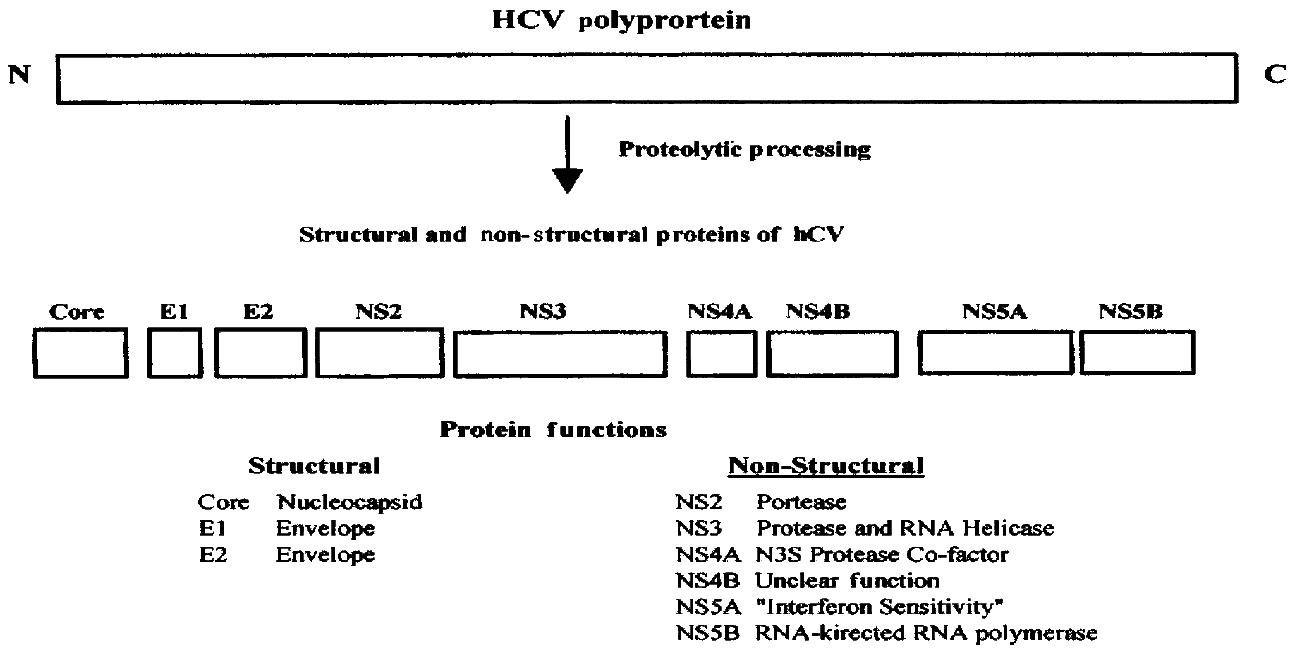

After the discovery of HCV, its entire genome was cloned and sequenced in several laboratories[5-8]. HCV is a member of the Flavivaridae family. Once HCV infects cells, the positive, single stranded RNA genome is translated into a polyprotein of 3010 to 3033 amino acids, depending upon the strain (Figur e 1). The viral RNA is not capped and translation occurs via an internal ribosome entry site (IRES) at the 5’ end of the viral RNA[9,10]. The mechanis m of translation of uncapped viral RNA therefore differs from that used by virtu ally all cellular mRNAs which are capped at their 5’ ends.

Both host cell and viral proteases cleave the HCV polyprotein into severa l smaller polypeptides (Figure 1). The major structural proteins are core prote in and two envelope proteins called E1 and E2. Core protein forms the nucleocap sid of the mature virion and E1 and E2 are present in the viral envelope. A small polypeptide called P7 is also generated as a result of cleavage at the E2-NS 2 junction but its function is not clear. Four major non-structural proteins called NS2, NS3, NS4, and NS5 are generated, two of which, NS4 and NS5, are furth er processed into smaller polypeptides called NS4A, NS4B, NS5A, and NS5B. The non-structural proteins have enzymatic functions that are critical for viral replica tion in cells, such as RNA helicase (NS3), protease (NS2, NS3-NS4A complex) and RNA polymerase (NS5B) activities. NS5A has been implicated in determining sensi tivity to interferon alpha.

Figure 1 HCV proteins and their functions.

The positive-stranded RNA of about 10000 nuc leotides is translated into a polyprotein of approximately 3000 amino acids. The polyprotein is proteolytically cleaved into several smaller proteins. Core, E1, and E2 are structural polypeptides. Core protein is the virus nucleocapsid and E 1 and E2 are viral envelope proteins. A small polypeptide known as P7 (not shown ) is also produced by additional cleavage between E2 and NS2. The major non-str uctural proteins are NS2, NS3, NS4, and NS5. NS4 is further processed into NS4A a nd NS4B and NS5 into NS5A and NS5B. NS2 and part of NS3 are proteases that proce ss the viral polyprotein. NS3 also has RNA-helicase activity. NS4A is a cofacto r for the NS3 protease and NS5B is an RNA-dependent, RNA polymerase. The functi ons of NS4B and NS5A are less well understood but NS5A is thought to play a role in determining sensitivity to interferon.

HCV replication and interactions with host cells

Little is known about the fundamental aspects of HCV replication, primarily beca use a robust cell culture has not been established. Although viral proteins and RNA components involved in critical steps in HCV replication are known, very li ttle is understood about the mechanistic details or the role of accessory host cell factors. Some of the basic steps in HCV replication that occur in infected cells are outlined here.

After infection of cells, HCV RNA must be translated into protein. HCV RN A translation is initiated by internal ribosome binding, not by 5’-end depend ent mechanisms[9,10]. Internal initiation is specified by an IRES ele me nt. Such elements were first discovered in the genomes of picornaviruses[11]. The IRES is believed to require the set of canonical translation initiation factors in order to function. In addition, IRES function is also thought to be dependent on other cell proteins. However, no single cell protein has been shown to be dispensable for the function of all IRESes.

HCV RNA must be unwound for efficient protein synthesis to occur. This process is catalyzed by a RNA helicase that is part of the viral NS3 protein. The three -dimensional structure of the HCV NS3 helicase domain has been determined and details about its function are emerging[12-14]. At the present time, it is not known if host cell co-factors are necessary for optimal functioning of the NS3 helicase. Cellular RNA helicases have also been shown to bind to the HCV core protein[15-17], however, it is not known if they also play a role in unwinding viral RNA.

After its synthesis, the HCV polyprotein is processed into the structural and no nstructural proteins. Proteolytic cleavages between structural polypeptides are catalyzed by signal peptidase in the endoplasmic reticulum. Two virally encode d proteases, NS2 and NS3, catalyze the other cleavages of the HCV polyprotein. The NS3 protease contains a trypsin-like fold and a zinc-binding site and is c omplexed with the viral protein NS4A[18,19].

HCV RNA must be replicated to produce more virions. The viral protein NS5B is an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. NS5B bears some similarity and motif organizati on to poliovirus polymerase and human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) reverse transcriptase but adopts a unique shape due to extensive interactions between th e fingers and thumb polymerase subdomains that encircle its active site[20]. The precise mechanism of action of the HCV NS5B polymerase is not known. C ellular or viral protein or RNA binding partners that function as subunits or in itiation factors may be necessary for optimal activity.

The replication rate of HCV in human hosts is estimated to be extremely high. It appears that the estimated half-life of a viral particle is 2.7 h with pr oduction and clearance of about one trillion viral particles a day[21] . This rate of virion production is approximately 1000 times greater than that estimated for HIV-1. Factors responsible for the high rate of HCV replication are not entirely understood. This rapid rate of replication can explain the develo pment of mutant strains or quasispecies that occur after HCV infection. It may a lso make development of an effective vaccine difficult.

DRUG TARGETS FOR THE TREATMENT OF HCV INFECTION

“Non-specific” anti-viral agents for HCV infection

The currently available drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C are anti-viral a gents not specifically directed against HCV. The United States Food and Drug Adm inistration (FDA) has approved several preparations of recombinant interferon al pha for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Interferon alpha is a suboptimal t reatment in that only about 20% or less of patients who complete a one year cour se of treatment respond successfully as determined by the inability to detect HCV in serum 6 mo after the drug is stopped[22]. Numerous adverse even ts are also associated with interferon alpha, most notably flu-like symptoms, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and depression. Interferon alpha must be administe red by injection 3 times a week. Newer preparations of interferon alpha-2b complexed with polyethylene glycol have been developed[23]. These so-cal led “PEG-ylated” interferon alphas are released more slowly and evenly into the bloodstream and need only be administered by injection once a week. “PEG -ylated” interferon alphas will likely be approved for the treatment of chron ic hepatitis C in the United States in the year 2000 or 2001.

The combination of interferon alpha-2b plusing oral ribavirin is approved in many countries for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C. Combination treatment for 6 mo leads to no detectable virus in serum 6 mo after stopping thera py in approximately 40% of subjects[24-26]. The major adverse event as sociated with ribavirin is hemolytic anemia, which in rare cases can be life thr eatening. VX-497 is a compound in development that inhibits inosine monophospha te dehydrogenase and may have antiviral affects similar to those of ribavirin[27]. VX-497 is being studied in combination with interferon alpha to e stablish if it is as effective as ribavirin with a similar or preferable adverse events profile.

Other cytokines have also been tested in the treatment of HCV infection. A recent report of a pilot study suggests that interleukin-10 may slow the deve lopment of liver fibrosis in subjects with chronic hepatitis C[28]. Inte rleukin-10, however, was not shown to have anti-viral activity against HCV.

Agents directed against HCV non-structural proteins

The next generation of drugs for the treatment of hepatitis C will likely be dir ected against non-structural HCV proteins with known enzymatic activities. Thre e major targets are the NS3 protease, NS3 helicase, and NS5B RNA-directed RNA polymerase. The fact that these proteins have enzymatic activities that can be mea sured in vitro make them amenable to high-throughput screening techniques f avored by pharmaceutical chemists. This obviates the need to grow HCV in cell cultures or in small animals, tasks that have eluded investigators.

The three-dimensional structure of the HCV NS3 protease domain has been determi ned by X-ray crystallography[18,19]. In addition, the structure of the NS3 protease domain complexed with an inhibitor has recently been established[29]. Armed with this knowledge, chemists can use rationale drug design to synthesis compounds to inhibit protease activity. Rational drug design can be c ombined with combinatorial chemistry in which a library of thousands or more str ucturally similar molecules is tested against the target. By combining rational drug design and combinatorial chemistry with high throughput screening techniques that measure enzymatic activity, N3S protease inhibitors can be identified, fu rther developed and ultimately tested in infected chimpanzees and humans.

Similar methods can be used to identify inhibitors of the N3S helicase domain and NS5B RNA dependent RNA polymerase. The three-dimensional structures of these proteins are also known[12-14]. Although human cells have RNA helicas es, their mechanism of action is probably different than RNA helicases of viruses[30]. Animal cells do not have RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, making N S5B an attractive target for an anti-viral agent.

Agents directed against HCV RNA

HCV RNA differs from cellular mRNA. First, it has a unique ribonucleotide seque nce. Second, as outlined above, HCV RNA is uncapped and translation is initiated via an IRES. Third, the viral RNA must be efficiently packaged into the matur e virions. These features make the HCV RNA a potential target for anti-viral drugs.

Ribozymes are catalytic RNA molecules that can be designed to cleave speci fic RNA sequences. Ribozymes therefore have potential utility as drugs against RNA viruses, including HCV. Investigators at Ribozyme Pharmaceuticals have deve loped ribozymes against conserved genomic sequences in HCV[31]. These ri bozymes cut the viral RNA at specific sequences and are able to inhibit HCV RNA -directed protein synthesis and HCV RNA replication in in vitro systems. It is anticipated that a ribozymes against HCV will be tested in human clinical tr ials in the next couple of years.

HCV RNA is translated by internal ribosome binding mediated by an IRES[9,10]. The IRES adopts a tertiary structure that is necessary for function[32,33]. Interference with IRES structure or function is a logical approach to attacking HCV replication. Antisense olignucleotides targeted to a stem-loop s tructure within the IRES have been shown effective at inhibiting HCV gene expres sion[34,35]. Other small molecule inhibitors can potentially be designed to inhibit HCV IRES function, which can be measured using in vitro assays a daptable to high throughput screening methods.

HCV RNA genomes must be packaged into newly synthesized virions. This is likely mediated by specific interactions between sequences in RNA and core prote in. Synthetic oligonucleotides corresponding to sequences in the 5’ region of the HCV genome have been shown to bind to core protein[36]. Agents that block HCV RNA binding to core protein could be useful as inhibitors of virion pr oduction.

Agents directed against other targets of HCV

HCV presumably gains access to hepatocytes, and possibly other cells, by binding to a plasma membrane protein receptor or receptors. HCV envelope protein s E1 and E2 have been shown to interact with plasma membranes of hepatocytes and other cells[37]. E1 and E2 may form a heteromeric complex[38], however, it is not clear if their association is necessary for binding to cell m embranes.

The receptors for HCV entry into liver cells are also not presently known. Howe ver, an interaction between HCV E2 and a plasma membrane protein CD81 has been described and characterized in some detail[39,40]. It is difficult to est ablish if this interaction mediates HCV entry into cells, primarily because a ro bust cell culture system for HCV is not currently available. Even if CD81 or other proteins that bind to HCV E1 and E2 are not receptors that mediate viral entr y, knowledge of these interactions could lead to the development of drugs that inhibit the binding of HCV to cells. Additional experimental work that may lead to the definitive identification of HCV receptors could also lead to the developm ent of viral entry inhibitors. Structural analysis of the interactions of viral envelope proteins with cellular receptors should be of tremendous value in the d evelopment of drugs as it will be in the case of HIV-1[41,42].

The core protein of HCV is another potential target for the development of anti -viral drugs. In infected cells, HCV core protein is synthesized on the endopla smic reticulum membrane with a large domain facing the cytoplasm[43]. HCV core protein has been shown to form multimers[44] and the self-intera ction of core protein is likely important in the assembly of the virion nucleoca psid. HCV core protein expression may also influence critical processes that hav e implications for cellular pathophysiology. Core protein may play a role in tra nsformation and oncogenesis[45] or be involved in regulating apoptosis a s it has been shown to bind to the cytoplasmic domain of lymphotoxin-β receptor, a member of the tumor necrosis receptor protein family[46]. HCV core protein also binds to a cellular RNA helicase and this interaction may adversely affect host cell protein synthesis and provide the viral RNA with enhanced access to the cell’s protein synthesis machinery[15-17]. Inhi bitors of core protein self-assembly or its interactions with other cellular pr oteins could therefore be useful in the treatment of hepatitis C.