Published online Oct 15, 1998. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v4.iSuppl2.35

Revised: May 12, 1998

Accepted: June 9, 1998

Published online: October 15, 1998

AIM: To explore the therapeutic effect of chemoembolization in hepatic metastases in colorectal carcinoma.

METHODS: Forty patients underwent chemoembolization of metastatic liver lesion from colorectal carcinoma. Selective angiography of the hepatic a rtery was performed to identify the feeding vessels of the metastatic lesion. The injected chemoemulsum consisted of 100 mg 5-fluorouracil, 10 mg mit omycin C and 10 mL lipiodol ultra fluid in a total volume of 30 mL. Gel foam embolization then followed until stagnation of blood flow was achieved. Patients were evaluated for response, over all survival, and side effects.

RESULTS: Overall median survival time from date of first chemoembolization was ten mo. Median survival time of cirrhotic patients with class A and B by Child-Pugh classification was 24 and 3 mo, respectively. The difference was significant, (P < 0.01). Patients with metastatic disease confined to the liver did better than those who also had extrahepatic disease, with median survivals of 14 and 3 mo, respectively (P < 0.02). There were significant differences in that median survival of patients with hypervascular metastases was longer than that of patients with hypovascular metastases. The most common side effects were transient fever, abdominal pain and fatigue. Three patients died within one mo from the procedure.

CONCLUSION: The therapeutic effect of systemic chemotherapy in hepatic metastases of large intestinal carcinoma was not satisfactory and there were more side effects, whereas the therapeutic effect of selective chemoembolization was promising and there were less side effects. Selective chemoembolization may be an effective first-line therapy in hepatic metastases of large intestinal carcinoma.

- Citation: Xiao XW. Value of selective chemoembolization in the treatment of hepatic metastases in colorectal carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol 1998; 4(Suppl2): 35-37

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v4/iSuppl2/35.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v4.iSuppl2.35

The liver is the most common site of metastatic disease in large intestinal carcinoma, and hepatic involvement determines the survival duration and quality of life of affected patients. Approximately 20% of patients dying with metastatic disease have liver involvement exclusively, with an additional 40% having disease at other sites as well[1]. Median survival ranges from 6 to 16. Eight mo in various series and is greatly influenced by the extent and surgical resectability of the metastases[2]. Systemic therapy has not been very effective for metastatic large intestinal carcinoma. Intravenous 5-fluorouracil (5-Fu) with leucovorin is currently the most widely used chemotherapeutic regimen. The median survival was 11.5 mo[3]. A recent meta-analysis of seven randomized trials evaluated tumor response and overall survival. These trials compared HAI hepatic arterial infusion using floxuridine (5-fluoro-2-deoxyuridine) with intravenous chemotherapy. Survival analysis showed a statistically significant advantage for HAI compared with controls who received no treatment[4]. The rationale for regional chemotherapy or chemoembolization (CE) arises from the fact that metastatic carcinoma to the liver derives its blood supply primarily from the hepatic artery. Because of the vascular anatomy of the liver and the angiographic approachability of many hepatic tumors, embolization therapy with or without intra-arterial chemotherapy has been attempted for many of these lesions. Patients enrolled in these trials have generally failed systemic and/or intra-arterial chemotherapy. To assess the result of CE, we report a phase II trail using a combination of 5-Fu, MMC, lipiodol ultra-fluide and gel foam embolization in patients who have failed systemic chemotherapy for liver metastases from large intestinal carcinoma. The response, survival time, side effects, and prognostic factors were evaluated.

Forty patients had hepatic lesions coexisting with functional disorders from histologically documented large intestinal carcinoma that had progressed or failed to systemic chemotherapy. Those who had received previous intra-arterial chemot herapy were excluded. All patients had bidimensionally measurable disease by computer tomography (CT), ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging, with no evidence of complete portal vein obstruction. The characteristics of 40 patients with stage IV large intestinal carcinoma were shown in Table 1.

| Data | |

| No. cases | 40 |

| Male: female ratio | 23:17 |

| Median age (range) | 50 (41-61) yr |

| Child-Pugh class | |

| A | 28 |

| B | 12 |

| Sites of hepatic metastases | |

| liver, one lobe | 4 |

| Liver, > one lobe | 24 |

| Liver and other sites | 12 |

| Vascularity of liver lesions | |

| Hypovascular | 11 |

| Hypervascular | 18 |

| Indeterminate | 11 |

Selective angiography of the hepatic artery was performed before CE to map the vascular anatomy and identify the primary feeding arteries of the metastatic lesions. Either the right or left hepatic artery was cannulated, followed by inject ion of the chemoemulsum, which consisted of 100 mg 5-Fu, 10 mg MMC, a nd 10 mL lipiodol ultra fluide, in a total volume of 30 mL.

Gelfoam embolization was then performed, until stagnation of blood flow was achieved. If the metastases was present in more than one lobe, each lobe was treated on a separate occasion,with an interval of four wk between the two procedures. Patients were hospitalized following CE until clinical recovery and stable liver function. Adjuvant medications included kefzol, morphone hydrochloride, metoclopramide, glucose, vit.B6, vit.C, and adequate intravenous hydration .

Laboratory studies including a complete blood cell count, coagulation parameters, chemistry, liver function tests, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels were obtained before the procedure. These laboratory tests were followed during the patient’s hospitalization and moly thereafter. A liver CT without contrast was obtained within 48 h following CE to determine the concentration of lipiodol ultra-fluide and serve as a baseline for measurements.The CT was repeated at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 mo afterwards.

Treatment responses, time of progression of disease, overall survival,and side effects were evaluated from the starting point of initial CE until time of progression or death. A partial response was defined as greater than 50 percent reduction in the sum of the products of the longest perpendicular diameters of the indicator lesions on CT. The response had to last at least three mo, and there must be no progression in any measurable lesion or appearance of new lesions. Survival was evaluated using the kaplan-Merier method and comparisons between groups with the log-rank method.

Forty patients with stage IV large intestinal carcinoma were treated in a phase II trial of CE of hepatic metastases. All patients progressed after treatment with 5-Fu-based systemic chemotherapy. Twenty-eight patients had metastatic disease that was exclusively confined to the liver. Eighteen patients with hypervascular and 11 with hypovascular hepatic lesions had liver function damaged. Median follow-up duration for the 40 patients was eight mo (range, 1-31). All patients were assessable for side effects and survival.

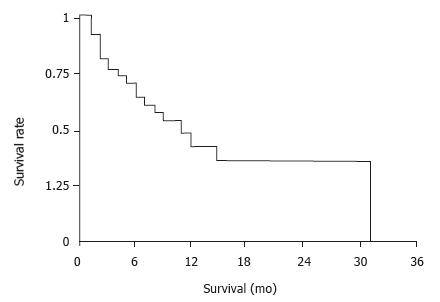

Treatment response was evaluated with follow-up CT scans in 35 patients in this study. Eight patients had a partial response. Median duration of response was study. Eight patients had a partial response. Median duration of response was seven mo. An additional 14 patients had a more than 25 percent reduction in the sum of the products of indicator lesions. Median baseline CEA in 35 patients with an elevated level was 1088 ng/mL and dropped to a median of 175 mg/mL after CE. Eighteen of 29 patients had a more than 50 percent reduction in their CEA levels. In those 29 patients, median CEA reduction was 64 percent. Overall median survival from date of first CE procedure was ten mo (Figure 1).

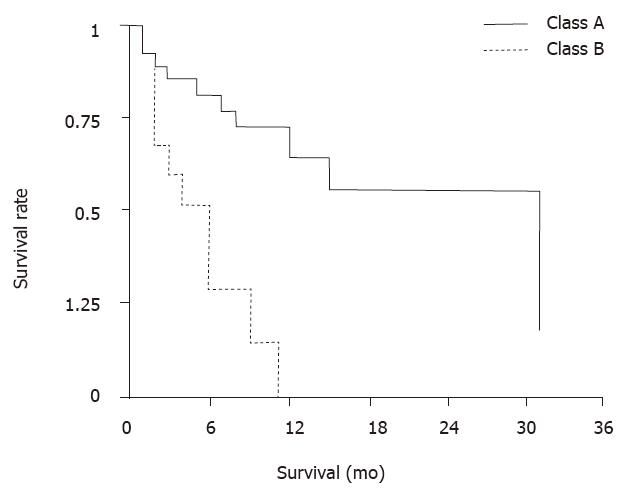

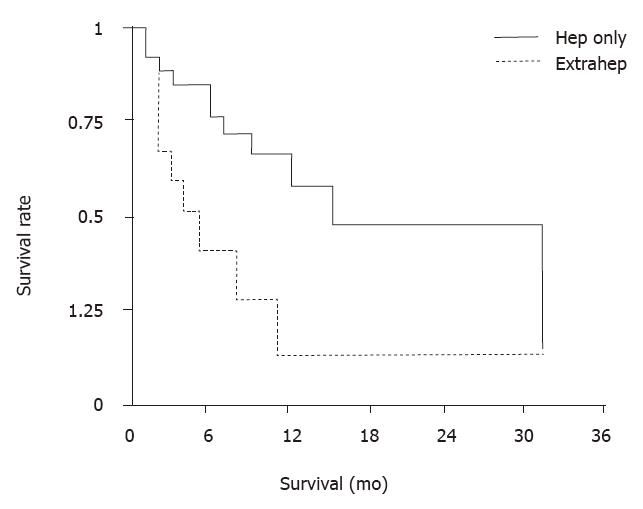

Several side effects occurred first in most patients during the 4th-7th d following CE. These included abdominal pain, fever, and elevated transaminases lasting no more than 2 wk. All patients developed a fatigue syndrome lasting two to 4 wk. Six patients had pernicious ascites. One patient developed peritonitis and one had sepsis. Cholecystectomy was required for one patient because of necrotic cholecystitis. Three patients died from deterioration of the disease within one mo after the procedure. Comparisons between subgroups of patients by identifying several possible prognostic factors associated with survival revealed that there was no significant difference in overall survival between males and females. A significant difference in median survival of cirrhotic patients with class A and B (P < 0.01), by Child-Pugh classification was found, of 24 and 3 mo, respectively, as seen in Figure 2. Patients with metastatic disease confine d to the liver did better than those who also had extrahepatic disease, with median survival of 14 and 3 mo, respectively (P < 0.02), as seen in Figure 3. Patients with hepervascular metastases had a median survival of 11 mo and those with hypovascular metastases only 5 mo. There were significant differences in survival for different baseline levels of aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Eleven patients with norm al baseline aminotransferase (≤ 25 u, karmen method) had a median survival of 14 mo and those with elevated levels only 5 mo (P < 0.01). When c omparing 24 patients with normal alkaline phosphatase ( < 4.0, Bodansky method) with 15 patients with higher levels, median survivals were 24 and 4 mo, respectively (P < 0.01). The difference was significant. 23 patients with normal LDH ( < 450 u) had a median survival of 12 mo, which was significantly longer than those ten patients with higher levels, whose median survival was 2 mo (P < 0.01).

Hepatic involvement frequently determines the clinical status of patients with metastatic large intestinal carcinoma. There is no evident improvement in survival with systemic therapy of HAI compared with controls. CE has also been evaluated as a potentially beneficial approach in this setting. Hunt et al[5]reported a prospective, randomized trial with three groups: no therapy, embolization alone, or intra-arterial 5-Fu with embolization using degradable starch microspheres (the CE group). Median survival from confirmation of metastases w as 9.6 mo for controls, 8.7 mo for the embolization group, and13 mo s for the CE group. These differences, however, did not reach statistical significance. Lang and Brown[6]treated 46 patients by means of selective CE with doxorubicin and ethiodized oil. One year after treatment, 41 percent of patients were free of disease progression and 65 percent were alive. By the second year, the figures were 21 and 34 percent, respectively. In another recent study, 24 patients were randomized to receive embolization or CE using 5-Fu and recombinant alpha-2a-interferon. There was no significant difference between the two groups on survial time. The authors concluded that addition of more patients to this trial would be necessary. The principal goals of the current study were to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of CE on hepatic metastases from primary large intestinal carcinoma and to identify the prognostic factors. Local adminstration of chemotherapeutic agents, both with HAI and CE, produces 10%-20% higher response rates than the conventional systemic chemotherapy. We prefer to use CT scan to evaluate the partial responses, rather than CEA or other criteria, such as estimation of tumor size or physical examination.Despite relatively high response rates were found in several studies of HAI, survival has not been clearly improved[4]. Therefore, the importance of evaluating the response rate is questionable.

In our study, overall median survival from date of first chemoembolization was 10 mo. Patients with metastatic disease confined to the liver did better than those who also had extrahepatic disease, with median survivals of 14 and 3 mo, respectively (P < 0.02). There were significant differences in that median survival of patients with hypervascular metastases was longer than that of patients with hypovascular metastases (P < 0.01). There was significant difference in survival time between class A and class B cirrhotic patients, (P < 0.01), with that of class A longer than that of class B, suggesting that survival in patients with large intestinal liver metastases is closely related to Chil-Pugh classificant of hepatic cirrhosis. The side effects of CE are worthy of appraisement. Some of them, such as abdominal pain and fever, are seen in almost all patients. However, they rarely last more than 5 d, and only need symptomatic treatment. There is also a significant elevation in hepatic transaminase lev el shortly after the procedure. The fatigue syndrome that follows CE improves progressively but can last more than one mo. On the other hand, there were infrequent but severe complications, including infections and gallbladder necrosis.T he toxicities found in our study are consistent with those reported in the literature[4,5].

In conclusion, selective CE can be used as the first line treatment for hepatic lesions of large intestinal carcinome owing to its therapeutic efficacy, as well as less side effects.

E- Editor: Li RF

| 1. | Weiss L, Grundmann E, Torhorst J, Hartveit F, Moberg I, Eder M, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Napier J, Horne CH, Lopez MJ. Haematogenous metastatic patterns in colonic carcinoma: an analysis of 1541 necropsies. J Pathol. 1986;150:195-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 1] [Cited by in Crossref: 497] [Cited by in RCA: 456] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wood CB, Gillis CR, Blu mgart LH. A retrospective study of the natural history of patients with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Clin Oncol. 1976;2:285-288. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: 1] |

| 3. | Hunt TM, Flowerdew AD, Birch SJ, Williams JD, Mullee MA, Taylor I. Prospective randomized controlled trial of hepatic arterial embolization or infusion chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and degradable starch microspheres for colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 1990;77:779-782. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: 1] |

| 4. | Martinelli DJ, Wadler S, Bakal CW, Cynamon J, Rozenblit A, Haynes H, Kaleya R, Wiernik PH. Utility of embolization or chemoembolization as second-line treatment in patients with advanced or recurrent colorectal carcinoma. Cancer. 1994;74:1706-1712. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: 3] |

| 5. | Lang EK, Brown CL. Colorectal metastases to the liver: selective chemoembolization. Radiology. 1993;189:417-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited in This Article: 2] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |