Published online Feb 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i7.101467

Revised: December 2, 2024

Accepted: December 17, 2024

Published online: February 21, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 23.6 Hours

With the widespread use of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, more and more gastric polyps (GPs) are being detected. Traditional management strategies often rely on histopathologic examination, which can be time-consuming and may not guide immediate clinical decisions. This paper aims to introduce a novel classification system for GPs based on their potential risk of malignant transformation, categorizing them as "good", "bad", and "ugly". A review of the literature and clinical case analysis were conducted to explore the clinical implications, mana

Core Tip: When performing endoscopy of the upper gastrointestinal tract, physicians often find gastric polyps (GPs), which are, for the most part, harmless. However, physicians need to have an in-depth knowledge of diagnostic tools, therapeutic strategies, and screening procedures, especially for those polyps with a potential risk of becoming cancerous. This paper introduces a new classification system for GPs based on the possible risk of cancerous transformation of the polyp, with three different classifications, namely, “good”, “bad”, and “ugly”, corresponding to different interventions and management by the clinician and influencing the different prognoses of the patients.

- Citation: Liao XH, Sun YM, Chen HB. New classification of gastric polyps: An in-depth analysis and critical evaluation. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(7): 101467

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i7/101467.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i7.101467

Gastric polyps (GPs) are increasingly being detected due to the widespread use of upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy. Traditional management strategies often rely on histopathologic examination, which can be time-consuming and does not always guide immediate clinical action. The new classification by Costa et al[1] aims to simplify this process by providing a clear and practical framework for clinicians to diagnose, manage, and characterize GPs.

The “good” category includes GPs that are generally benign and have a low risk of malignant transformation. The main ones include fundic gland polyps (FGPs), inflammatory fibrous polyps (IFPs), and ectopic pancreas (EP).

FGPs are the most common type, accounting for approximately 80% of all GPs[2]. Usually due to Helicobacter pylori

| Classification |

| Good |

| Fundic gland polyps |

| Sporadic fundic gland polyps |

| Syndromic fundic gland polyps |

| Inflammatory fibroid polyps |

| Ectopic pancreas |

| Bad |

| Gastric hyperplastic polyps |

| Gastric adenomas |

| Intestinal type |

| Foveolar type |

| Pyloric gland type |

| Oxyntic gland type |

| G-NETs |

| Type 1 |

| Type 2 |

| HaPs |

| Sporadic HaPs |

| Gastric inverted HaPs |

| Ugly |

| Type 3 G-NETs |

| Early gastric cancer |

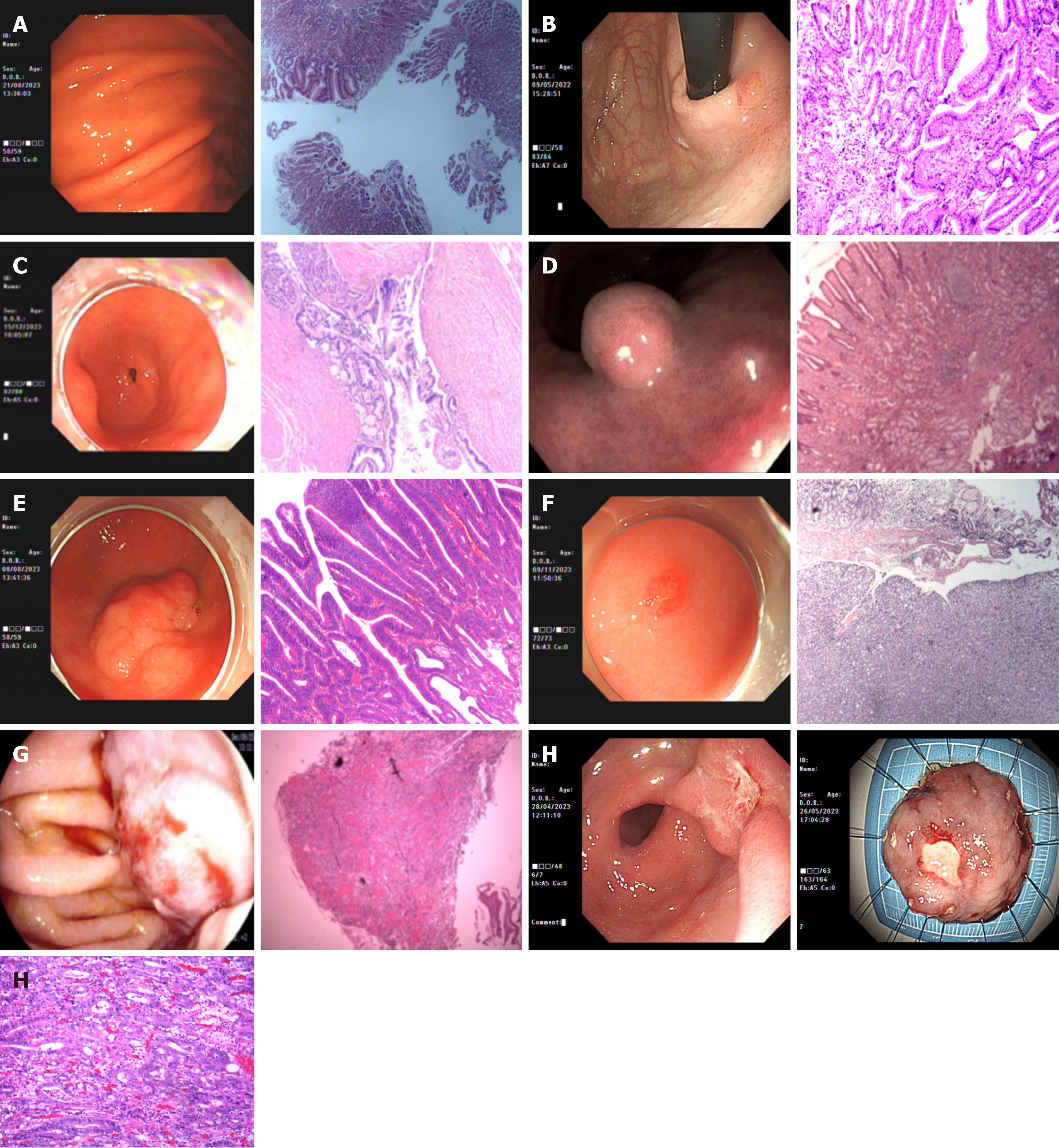

IFPs are a relatively rare type of tumor in the GI tract, which can occur throughout the GI tract, but most often involve the gastric antrum. Clinical symptoms are related to the site of occurrence, with the stomach presenting primarily with outflow obstruction; small bowel lesions may present with obstruction, and intussusception is common; the diagnosis of IFPs relies heavily on endoscopy and histologic examination. Under endoscopic examination, the visible mass is located in the submucosal layer, which may be sessile or pedunculated, and varies in size. Histologically, the mass is composed of scattered short to long spindle-shaped cells and a greater number of eosinophils, with a loose stroma and rich vascularity. Treatment is mainly surgical or endoscopic complete excision. IFPs have a good prognosis and are considered benign lesions with rare recurrence after local excision (Figure 1B and Table 1).

EP is a congenital developmental malformation in the GI tract, which is most commonly found in the greater curvature or posterior wall of the gastric sinus and anterior pyloric region. The majority of gastric EPs are asymptomatic, but they may also present with symptoms such as obstruction and hemorrhage when they grow in certain specific locations or undergo other pathologic changes[5,6]. Due to the lack of specific clinical manifestations, the differential diagnosis of EP is difficult and still relies on pathologic diagnosis after endoscopic-guided fine-needle aspiration[7]. For asymptomatic patients with EP, follow-up observation can be performed, and if the EP tissue is found to be enlarged, signs of malignancy exist, or the combination of related symptoms are found in the course of follow-up, surgical treatment may need to be considered (Figure 1C and Table 1).

The “bad” category includes GPs with an intermediate risk of malignancy, such as hyperplastic polyps, adenomas, types 1 and 2 neuroendocrine tumors, and hamartomatous polyps; this article focuses on hyperplastic polyps and adenomas.

Gastric hyperplastic polyps (GHPs) are non-neoplastic polyps elevated on the surface of the gastric mucosa; they are often small, usually not exceeding 5 mm in diameter, but larger ones up to 12 cm have been reported, often multiple[8]. These polyps are characterized by lengthened and dilated glands with normal cell differentiation.

GHPs have long been considered to be benign tumors with little chance of becoming cancerous. The etiologic cause of hyperplastic polyps has not been fully clarified, but it may be related to genetic factors and long-term inflammatory stimuli, such as H. pylori infection, chronic atrophic gastritis, ulcerative colitis, and other chronic inflammatory diseases.

In terms of treatment, small and asymptomatic hyperplastic polyps usually do not require specific treatment, and only regular review is needed.

It is worth noting that although it was previously thought that sporadic hyperplastic polyps were highly unlikely to become cancerous, recent opinion suggests that certain hyperplastic polyps may develop heterogeneous hyperplasia, and that GHPs larger than 1 cm, with a clitoral morphology, and in patients who have undergone previous gastrectomies are factors that contribute to the neoplastic transformation of GHPs[9]. Such polyps may require closer monitoring and potentially endoscopic resection. This classification emphasizes the importance of accurate identification, precise diagnosis, and timely intervention of these polyps to prevent potential neoplastic progression (Figure 1D and Table 1).

Gastric adenomas are a type of gastric polyp that is usually considered a benign epithelial tumor. Among GPs, gastric adenomatous polyps account for approximately 6% to 10% of all gastric epithelial polyps. Intestinal-type adenomas are localized polypoid lesions composed of a heterogeneously proliferating intestinal epithelium. They are the most common type of adenoma, usually occurring in areas where intestinal epithelial hyperplasia has occurred, such as the gastric antrum and gastric angles, and are most commonly seen in people over 60 years of age. They are usually isolated and tend to be less than 2 cm in diameter. Symptoms of gastric adenomas are usually unremarkable, but when present, they tend to manifest themselves in ways that may include mild epigastric pain or discomfort, nausea, anorexia, dyspepsia, weight loss, anemia, intermittent or persistent bleeding, or, rarely, obstruction[10].

Gastric adenomas of the intestinal type have a relatively high rate of carcinoma, especially when the glands are accompanied by gastric-type epithelial differentiation, and such hybrid adenomas have a higher risk of transformation to carcinoma[4]. This classification suggests that special attention should be given to polyps with these features during endoscopy (Figure 1E and Table 1).

The “ugly” category mainly refers to polyps with a high risk of malignancy that are highly aggressive. In this category, we focus on type 3 neuroendocrine tumors and early gastric cancer (EGC).

Type 3 gastric neuroendocrine tumors (G-NETs) are usually sporadic tumors, and in contrast to type 1 G-NETs and type 2 G-NETs, they do not have a specific disease background, such as autoimmune atrophic gastritis or gastrinoma. Type 3 G-NETs tend to be graded as G2, have a distant metastasis rate of approximately 50%, and have a relatively poor prognosis[11] (Figure 1F and G, Table 1).

Type 3 neuroendocrine tumors are classified as “ugly”, indicating a high risk of malignancy and aggressive behavior. The urgency and importance of a comprehensive evaluation of type 3 G-NETs, including endoscopy, imaging evaluation, pathology, and multidisciplinary discussion to develop an individualized treatment plan, such as the choice of surgical modality, was emphasized to improve patient outcomes and survival[12].

EGC is defined as gastric cancer in which cancerous tissue infiltration is confined to the mucosal or submucosal layer of the stomach, with or without lymph node metastasis, and is a T1-stage tumor, which may be accompanied by any N-stage lymph node status[13]. There are nearly 1 million new cases worldwide each year, and EGC accounts for 15%-57% of new gastric cancers, depending on the geographic region and the implementation of a screening program. The clinical symptoms of EGC are usually not obvious, and 80% of patients may have no obvious symptoms; hence, it is termed as “invisible killer”. When symptoms do appear, they may include weight loss, fatigue, epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite, which can be easily confused with other GI disorders. Its diagnosis mainly relies on endoscopy and pathologic biopsy. The continuous improvement of endoscopy technology has led to a more refined diagnosis of lesion extent and infiltration depth, and the morphological features of EGC detected are more superficial and microscopic[14].

In terms of EGC treatment recommendations, endoscopic resection is the preferred treatment modality for EGC patients without the risk of lymph node metastasis, which mainly includes endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) and endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD). ESD can achieve complete resection of larger lesions, provide accurate pathological diagnosis, and ensure negative margins of the lesion, which makes it the preferred and standard endoscopic treatment modality for EGC (Figure 1H and Table 1).

The new classification system offers a significant advancement in the clinical approach to GPs, with the potential to improve diagnostic accuracy, simplify patient management, and enhance endoscopic practice.

Accurate morphological classification using white light endoscopy and chromoendoscopy (CE) is emphasized as a key aspect of the new classification system, according to the Paris classification[15]. CE, also known as dye spraying endoscopy, is an enhancement of conventional white-light endoscopy that involves the application of colored pigments, typically methylene blue, indigo carmine, and acetic acid, to the gastric mucosal surface. This technique accentuates tissue characteristics, creating a stark contrast between lesions and the normal gastric mucosa, thereby facilitating the identification of EGC and precise biopsy targeting. It enhances the detection rate of EGC and enables accurate delineation of the lesion margins and the extent of cancerous changes, significantly improving the completeness of EMR for EGC. Studies have demonstrated that CE offers significant diagnostic advantages over white-light endoscopy in the detection of EGC and precancerous lesions, with a sensitivity and specificity of 90% and 82%, respectively[16,17]. This approach ensures that clinicians can make informed decisions based on the endoscopic appearance of the GP, facilitating timely and appropriate intervention.

The classification system provides clear guidelines for patient management, from monitoring to intervention. For example, a 'good' GP may be monitored less frequently, while an 'ugly' GP requires immediate and active management. This tiered approach allows for personalized care based on each GP's individual risk.

It is anticipated that the introduction of this classification system will standardize endoscopic practice and ensure that patients receive appropriate care based on the risk stratification of their GPs.

The system emphasizes the need for continuing education and training of endoscopists to effectively identify and manage different types of GPs. This includes understanding the endoscopic features of each category and appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic measures.

Classification may also drive the development of new endoscopic techniques to better identify and characterize GPs, such as improved imaging techniques and advanced biopsy methods that can help accurately classify GPs during endoscopy.

Although the new classification system has made significant progress in GP management, it is not without its challenges. The potential for misclassification due to similarity in endoscopic appearance and the need for biopsy for definitive diagnosis are significant limitations.

The complexity of differentiating GPs with similar endoscopic features but different malignant potential requires endoscopists to maintain a high level of suspicion and rely on histologic confirmation. This is particularly challenging in situations where the endoscopic appearance is not specific.

Reliance on histology for accurate classification may lead to delays in patient management and increased demand for specialized pathology services. In addition, the accuracy of histology-based classification may be affected by the quality of the biopsy sample and the expertise of the pathologist.

Costa et al's classification system lays the foundation for future research in GP management, including predictive biomarkers of tumor transformation and personalized drug approaches based on individual patient risk profiles[1].

Identifying biomarkers that predict GP malignant potential could refine classification systems and inform treatment decisions. This may include molecular markers that indicate the malignant potential of GPs, allowing for more targeted interventions.

Incorporating genetic and molecular profiling into classification systems may lead to personalized management strategies for people with GPs. This may involve customizing treatment based on an individual's genetic susceptibility and the molecular characteristics of his/her GPs.

The new classification of GP by Costa et al[1] represents a paradigm shift in diagnostic strategies and patient management for GPs. By categorizing GPs according to their malignant potential, the system provides a clear framework for clinical decision-making. Although challenges remain, the impact of the system on standardizing endoscopic practice and improving patient outcomes is significant. Future research and technological advances will further refine this classification and increase its clinical utility.

| 1. | Costa D, Ramai D, Tringali A. Novel classification of gastric polyps: The good, the bad and the ugly. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:3640-3653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Carmack SW, Genta RM, Schuler CM, Saboorian MH. The current spectrum of gastric polyps: a 1-year national study of over 120,000 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:1524-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Martin FC, Chenevix-Trench G, Yeomans ND. Systematic review with meta-analysis: fundic gland polyps and proton pump inhibitors. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:915-925. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Abraham SC, Montgomery EA, Singh VK, Yardley JH, Wu TT. Gastric adenomas: intestinal-type and gastric-type adenomas differ in the risk of adenocarcinoma and presence of background mucosal pathology. Am J Surg Pathol. 2002;26:1276-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | LeCompte MT, Mason B, Robbins KJ, Yano M, Chatterjee D, Fields RC, Strasberg SM, Hawkins WG. Clinical classification of symptomatic heterotopic pancreas of the stomach and duodenum: A case series and systematic literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2022;28:1455-1478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 6. | Sharma SB, Gupta V. Ectopic pancreas as a cause of gastric outlet obstruction in an infant. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2004;23:219. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Riyaz A, Cohen H. Ectopic pancreas presenting as a submucosal gastric antral tumor that was cystic on EUS. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;53:675-677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ghazi A, Ferstenberg H, Shinya H. Endoscopic gastroduodenal polypectomy. Ann Surg. 1984;200:175-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Imura J, Hayashi S, Ichikawa K, Miwa S, Nakajima T, Nomoto K, Tsuneyama K, Nogami T, Saitoh H, Fujimori T. Malignant transformation of hyperplastic gastric polyps: An immunohistochemical and pathological study of the changes of neoplastic phenotype. Oncol Lett. 2014;7:1459-1463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chandrasekhara V, Ginsberg GG. Endoscopic management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2011;13:532-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Panzuto F, Ramage J, Pritchard DM, van Velthuysen MF, Schrader J, Begum N, Sundin A, Falconi M, O'Toole D. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for gastroduodenal neuroendocrine tumours (NETs) G1-G3. J Neuroendocrinol. 2023;35:e13306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | The Paris endoscopic classification of superficial neoplastic lesions: esophagus, stomach, and colon: November 30 to December 1, 2002. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:S3-43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1117] [Cited by in RCA: 1327] [Article Influence: 60.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 13. | Ngamruengphong S, Abe S, Oda I. Endoscopic Management of Early Gastric Adenocarcinoma and Preinvasive Gastric Lesions. Surg Clin North Am. 2017;97:371-385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Uedo N, Yao K. Endoluminal Diagnosis of Early Gastric Cancer and Its Precursors: Bridging the Gap Between Endoscopy and Pathology. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2016;908:293-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shaib YH, Rugge M, Graham DY, Genta RM. Management of gastric polyps: an endoscopy-based approach. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:1374-1384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Young E, Philpott H, Singh R. Endoscopic diagnosis and treatment of gastric dysplasia and early cancer: Current evidence and what the future may hold. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:5126-5151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 17. | Numata N, Oka S, Tanaka S, Yoshifuku Y, Miwata T, Sanomura Y, Arihiro K, Shimamoto F, Chayama K. Useful condition of chromoendoscopy with indigo carmine and acetic acid for identifying a demarcation line prior to endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |