Published online Feb 14, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i6.100295

Revised: November 8, 2024

Accepted: December 9, 2024

Published online: February 14, 2025

Processing time: 150 Days and 16.3 Hours

In this article, we comment on the article by Blüthner et al. The article provides a comprehensive analysis of the factors contributing to the late detection of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis within a German cohort. It highlights the conse

Core Tip: This article focuses on the difficulties in detecting inflammatory bowel disease and the consequences of diagnostic delays. By analyzing factors related to both patient behavior and physician practices, the article underscores the critical need for early assessment to prevent disease progression and complications. Emphasizing the importance of targeted interventions, such as improved screening tools and patient education, this discussion highlights the ongoing challenges in timely inflammatory bowel disease diagnosis and the need for enhanced healthcare strategies.

- Citation: Minea H, Singeap AM, Huiban L, Muzica CM, Stanciu C, Trifan A. Patient and physician factors contributing to delays in inflammatory bowel diseases: Enhancing timely diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(6): 100295

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i6/100295.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i6.100295

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) characterized by a disease course marked by numerous relapses, significantly affecting the quality of life of patients. In recent decades, their prevalence has continuously increased in many regions of the world[1,2]. The etiology is complex, involving an interaction between the intestinal microbiota, immune system dysfunction, and the intervention of various environmental factors in patients with genetic susceptibility[3-5]. The clinical symptomatology varies among patients, with differences by the location and extent of intestinal inflammatory lesions[6]. Beyond the significant impact on the digestive tract, approximately 25%-40% patients with IBD present with extraintestinal manifestations that could be attributed to various conditions, which complicates the accurate definition of these pathological states[7].

Delayed diagnosis postpones early treatment, promoting the emergence of adverse effects with a severe impact on disease progression and the development of complications that can lead to irreversible damage, thereby increasing the need for surgical interventions[8]. Therefore, the morbidity caused by these diseases substantially increases costs and places additional pressure on healthcare systems[9]. IBD symptoms often overlap and develop with other concurrent disorders, particularly irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), complicating the physician’s ability to make a prompt diagnosis. In UC, delayed disease detection increases the risk of developing extensive colitis, severe bleeding, and toxic megacolon. These conditions are associated with a higher hospitalization rate and a significantly increased need for aggressive treatments, including corticosteroids and biological therapies[10]. Moreover, a delay of more than 2 months in initiating appropriate treatment represents a significant risk factor that is crucial in disease progression[11].

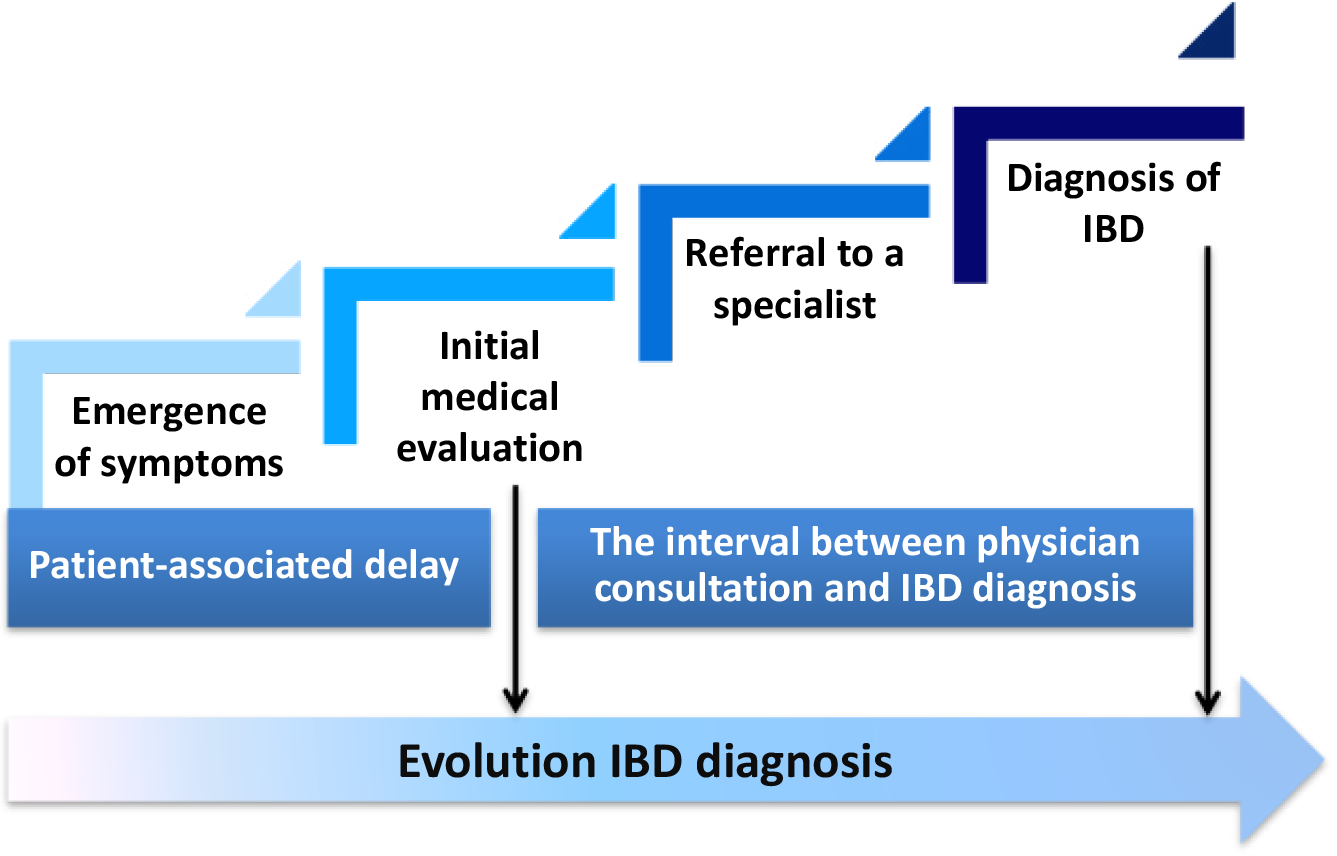

Prevention strategies focus on the implementation of awareness campaigns aimed at achieving early diagnosis using non-invasive and cost-effective tools. The use of a questionnaire to obtain a predictive score based on clinical symptomatology and the evaluation of fecal calprotectin has recently been proposed as a simple and affordable approach for early diagnosis of IBD[12]. A recent study by Blüthner et al[13], published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, provides a comprehensive overview of the factors involved in the delay of IBD diagnosis, highlighting the characteristics that differentiate CD from UC. The study systematically identifies and analyzes predictors related to both patients and clinicians that are associated with prolonged presentation and evaluation (Figure 1). A key aspect of the study’s originality focuses on its detailed examination of patient behavior and characteristics that contribute to delayed seeking of medical care. Furthermore, the article offers a nuanced exploration of clinician-related factors that complicate diagnosis accuracy. The authors delve into the decision-making processes in clinical practice, examining how nonspecific causes might lead to initial misdiagnoses or failure to refer patients promptly to specialists[13].

Identifying the factors involved in increasing the time to diagnosis is crucial for defining priority areas for intervention. Studies conducted in Europe and Asia demonstrated that the time from initial symptom onset to seeking clinical help varied from 2 months to 8 years, with a longer duration observed in CD[14]. An online survey conducted by the European Federation of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Associations involving 4990 patients confirmed that 24.1% of the monitored subjects exhibited symptoms suggestive of CD at least 5 years before seeking a gastroenterological examination[15]. The symptomatology of CD is frequently mistaken for other conditions, including UC, intestinal infections, and drug-induced lesions. When alarm signals (i.e., bleeding, weight loss, and perianal disease) are absent, it becomes extremely difficult to differentiate CD from other diseases. In this context, the performance level of primary healthcare, the nonspecific nature of symptoms, and the heterogeneity of these diseases are the main factors underlying diagnosis delay. For this category of patients, debilitating symptoms that interfere with daily activities, such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and the presence of fistulas, are key factors prompting urgent medical attention, especially when there is a family history. In contrast, intermittent symptoms such as diarrhea and blood in the stool are not considered alarming signs that require immediate analysis[13]. As a result, patients often underestimate the severity of their condition, especially during periods of remission. This lack of awareness regarding the potential severity of CD results in exacerbated delays, as patients do not prioritize early medical consultation. Additionally, various barriers, such as logistical challenges, financial constraints, and long waiting times for appointments, significantly contribute to the prolonged postponement of care[16]. There is increasing evidence suggesting that ileal location is associated with the highest risk for delayed confirmation of a CD diagnosis, as this category of patients tends to have a lower likelihood of developing alarming symptoms (e.g., blood in the stool)[17].

The absence of reliable and non-invasive biomarkers for preclinical screening of the general population represents another cause of late presentation. There is often a long period between asymptomatic onset and the first medical consultation, which is only sought due to worsening disease progression and the appearance of complications. This is considered the natural course of CD, which often begins with minimal, asymptomatic inflammation that progressively worsens, becomes symptomatic and recurrent, with an increased potential for the development of strictures. According to data reported by specialists, there are approximately 8-9 years between the onset of disease recurrence and the development of strictures, often necessitating surgical intervention[15]. For example, Cantoro et al[16] monitored patients with CD lesions that were incidentally detected during endoscopy performed for associated diseases (i.e., ankylosing spondylitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, etc) and found that 72% developed specific symptoms within a timeframe similar to that of a group of surgically treated CD patients.

Another study focused on asymptomatic IBD patients who were incidentally detected during colonoscopy screening for colorectal cancer and who developed rectal bleeding and diarrhea within a relatively reduced period [25 months; interquartile range (IQR) 10.5-42 months]. These symptoms confirmed the presence of intestinal mucosal lesions and suggest that the disease was already relatively advanced at the time of diagnosis[9]. Comparing findings from different studies can provide a broad perspective on the global challenges of diagnosing CD. Nguyen et al[14] demonstrated that ileal involvement and the absence of alarming symptoms, such as lower gastrointestinal bleeding, were frequently associated with significant delays in seeking initial medical care.

This is consistent with the findings of the German study where patients frequently misinterpreted their symptoms, leading to increased waiting times before seeking medical consultations[13]. In a similar context, an Indian study reported significant delays in diagnosing CD, primarily due to the misattribution of symptoms and limited access to medical care. Due to a low level of awareness, patients in these regions presented late for specialist examination. This delay was further amplified by the nonspecific nature of the symptoms, mirroring findings from German and American studies. However, the Indian context highlighted the role of healthcare infrastructure in these delays and emphasized the need to improve patient education and access to medical care[18].

For UC, a study by Blüthner et al[13] demonstrated that patients seek specialized medical help earlier due to more alarming clinical signs, although numerous factors contribute to these delays. While rectal bleeding and the urgent need to defecate are specific to UC, they can sometimes be mistakenly attributed to less severe conditions, such as hemorrhoids. If patients experience mild forms of the disease, they may not perceive the need for urgent medical evaluation. Additionally, barriers to accessing healthcare, such as logistical challenges, financial constraints, and long waiting times for appointments, similarly affect these patients[13]. In contrast, Nguyen et al[14] observed that patients with UC typically experienced shorter diagnostic delays compared to those with CD, primarily due to the much more alarming nature of the symptoms, which prompted quicker medical consultations. Similar results were reported in a cohort of Italian patients who, due to the presence of typical UC symptoms such as rectal bleeding, were much more responsive in seeking immediate medical assistance, leading to shorter waiting times[16]. Despite the much more alarming clinical profile of UC compared to CD, the lack of patient education remains the primary cause of delayed seeking of the first specialist examination among Indian patients. Furthermore, it was found that in regions with limited access to healthcare, even UC patients with severe symptoms often faced significant delays before receiving an appropriate diagnosis[19].

Enhancing the patient’s understanding of the consequences of late detection of IBD and equipping them with self-monitoring tools is fundamental in promoting early diagnosis. Awareness programs that focus on the symptoms and risks associated with IBD may motivate individuals to seek medical attention at the first signs of the disease. Additionally, the adoption of digital health technologies could offer valuable insights for both patients and healthcare providers, aiding in early detection and the development of personalized treatment strategies[16].

Although considerable progress has been made in the management of IBD over the past few decades, the variability of clinical phenotypes creates challenges for diagnostic confirmation, leading to significant delays after the initial consultation. These delays impact the effectiveness of therapeutic options and can lead to severe complications[8]. Various studies have analyzed the differences in delay between the onset of symptoms and primary medical care, as well as those that occurred after the first consultation. While Vavricka et al[20] reported a significant delay in the phase of seeking medical help (> 24 months) for patients with CD, with the main predictors being age < 40 years at diagnosis [odds ratio (OR) = 2.15; P = 0.01] and ileal disease (OR = 1.69; P = 0.025), Nguyen et al[14] found that the delay from the first consultation to the final diagnosis was much greater in patients with UC[14,20]. If this interval exceeded 26 months, the risk of developing general complications significantly increased (OR = 8.22; P = 0.007) as well as the development of intestinal strictures (OR = 8.96; P = 0.012)[14].

Although the waiting time for patients until the first medical consultation was relatively comparable [CD: 2.0 months (IQR 0.5-6.0 months) vs UC: 1.0 months (IQR 0.5-4.0 months); P = 0.05], the results obtained by Blüthner et al[13] indicated that the total diagnostic time was more than twice as long in CD compared to UC [12.0 months (IQR: 6.0-24.0 months) vs 4.0 months (IQR 1.5-12.0 months); P < 0.001] because a longer period was needed to confirm the disease (5.5 months; IQR 0.75-23.5 months). In contrast, Cross et al[19] had demonstrated that a much longer diagnostic delay is correlated with age of over 60 years in CD patients. Cantoro et al[16] presented a similar perspective, suggesting that the advanced age of patients at their first medical examination and the complicated nature of the disease are the main predictors for prolonged time until the confirmation of a CD diagnosis. Due to the weak correlation between symptoms, intestinal inflammatory lesions, and disease severity, numerous diagnostic errors were recorded, significantly contributing to delays.

Various nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting, are frequently reported in CD and have a high potential to either mislead the diagnosis or lead to an underestimation of the disease’s severity. However, prolonged diarrhea and cutaneous manifestations lead to additional investigations and a faster diagnosis. Notably, a positive family history of IBD despite a shorter patient waiting time did not reduce the physician’s diagnostic time, likely due to the challenges in differentiating CD from other gastrointestinal disorders, even in the presence of a known genetic predisposition[13]. Another risk factor frequently identified in CD with ileal localization is the occurrence of gastric pain without diarrhea, which increases the likelihood of confusion with IBS[5]. The association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (commonly referred to as NSAIDs) use and delayed diagnosis confirmation could be explained by the similarity between the side effects of these medications and CD symptoms. As a result, this could reduce patients’ awareness, increasing the likelihood of misdiagnosis[21]. Moreover, rural provenance and symptom onset during summer months were additional predictors of delayed diagnosis due to difficulties in appointments with staff specialized in IBD[17].

In contrast, physician diagnostic time in UC was generally shorter, primarily due to the more specific and alarming nature of symptoms. The German study noted that severe symptoms such as fever shortened the diagnostic interval, while nonspecific symptoms like fatigue led to longer delays. Surprisingly, despite being a hallmark symptom of UC, rectal bleeding was not consistently associated with faster diagnosis, highlighting that even clear symptoms may not always lead to prompt medical action. Furthermore, a positive family history of IBD delayed physician diagnostic time in UC, which is contrary to the effect seen in CD. This suggests that while a family history might raise awareness, it does not necessarily expedite the diagnostic process, possibly due to physician over-reliance on symptom presentation or other diagnostic markers[13]. Other studies further emphasize the role of healthcare infrastructure in influencing physician diagnostic time. Hence, limited access to advanced diagnostic tools and less experienced practitioners contributed to prolonged diagnostic times[19]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for improving training and diagnostic protocols[16].

One of the primary strategies to improve disease detection is the implementation of effective screening tools in primary care settings. Given the time constraints faced by clinicians and the expanding knowledge base about rare diseases, there is a clear need for accessible, reliable diagnostic tools that can be employed early in the patient care pathway. The “red flags index for suspected CD” represents a method of diagnostic accuracy designed to distinguish healthy individuals from those with IBS and early-stage CD. This index is a valuable tool for primary care physicians who are often the first point of contact for patients with gastrointestinal complaints. By systematically assessing risk factors and symptoms, such as perianal fistula, family history of IBD, weight loss, and chronic abdominal pain, the index helps clinicians identify patients who may require further investigation into IBD[16].

Another promising tool is CalproQuest, an 8-item questionnaire designed to identify potential IBD patients by evaluating symptoms such as nocturnal diarrhea, mild fever, and rectal urgency. This tool is particularly useful in distinguishing IBD from functional gastrointestinal disorders, which could present with overlapping symptoms. Implementing such questionnaires in routine clinical practice could significantly reduce the time to diagnosis by prompting earlier referrals to specialists for patients who screen positive[22]. Noninvasive biomarkers, such as fecal calprotectin, are markers for gut inflammation, and testing is widely used for differential diagnosis. However, it could also be elevated in other conditions such as gastritis, polyps, or diverticulitis, and can be influenced by chronic medication use. Therefore, while calprotectin is a valuable tool for initial screening, it should be used in conjunction with other diagnostic methods to confirm IBD[23]. Given the diversity of disease phenotypes, which leads to considerable variability in clinical symptoms, it is improbable that a single biomarker could provide a precise diagnostic. This approach overlooks the intricate and multifactorial nature of IBD pathogenesis, which requires a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding rather than a narrow focus on individual molecular associations[24].

Future investigations should prioritize the generation of predictive models that incorporate genetic information to identify individuals at high risk for developing IBD, even before clinical symptoms manifest. Additionally, a deeper understanding of genetic predispositions and early epigenetic alterations could shed light on the initial triggers of IBD, especially for patients at risk of developing CD or UC. The use of multi-omics approaches offers a comprehensive perspective on the molecular mechanisms that influence the disease. Therefore, the integration of multi-omics platforms could provide a holistic view of the pathology to discover new biomarkers and therapeutic targets and ultimately improve the precision of diagnosing, monitoring, and treating IBD[3].

The timely diagnosis of IBD represents an essential factor to prevent complications and improve patient outcomes. Delays in detection could stem from various factors, including the complexity of symptoms, misattribution to less severe conditions, and differences in healthcare accessibility. Notably, patients with CD face a higher risk of prolonged diagnostic delays compared to those with UC, primarily due to the more variable and often subtle symptomatology of CD. Addressing these challenges requires a multifaceted approach that involves enhancing primary care screening tools, improving general practitioner education and training, and integrating advanced diagnostic technologies. Recognizing the unique diagnostic barriers faced by each patient population is crucial for optimizing IBD management and minimizing the impact of delayed diagnosis.

| 1. | Lu Q, Yang MF, Liang YJ, Xu J, Xu HM, Nie YQ, Wang LS, Yao J, Li DF. Immunology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutics. J Inflamm Res. 2022;15:1825-1844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 33.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Baldan-Martin M, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Tissue Proteomic Approaches to Understand the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2021;27:1184-1200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Nowak JK, Kalla R, Satsangi J. Current and emerging biomarkers for ulcerative colitis. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2023;23:1107-1119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang Y, Huang B, Jin T, Ocansey DKW, Jiang J, Mao F. Intestinal Fibrosis in Inflammatory Bowel Disease and the Prospects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy. Front Immunol. 2022;13:835005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 17.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li X, Zhang M, Zhou G, Xie Z, Wang Y, Han J, Li L, Wu Q, Zhang S. Role of Rho GTPases in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Death Discov. 2023;9:24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen X, Xiang X, Xia W, Li X, Wang S, Ye S, Tian L, Zhao L, Ai F, Shen Z, Nie K, Deng M, Wang X. Evolving Trends and Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Disease in Asia, 1990-2019: A Comprehensive Analysis Based on the Global Burden of Disease Study. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2023;13:725-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Rogler G, Singh A, Kavanaugh A, Rubin DT. Extraintestinal Manifestations of Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Current Concepts, Treatment, and Implications for Disease Management. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:1118-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 453] [Article Influence: 113.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sorrentino D, Nguyen VQ, Chitnavis MV. Capturing the Biologic Onset of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Impact on Translational and Clinical Science. Cells. 2019;8:548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rodríguez-Lago I, Zabana Y, Barreiro-de Acosta M. Diagnosis and natural history of preclinical and early inflammatory bowel disease. Ann Gastroenterol. 2020;33:443-452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chang JT. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2652-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 764] [Article Influence: 152.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manser CN, Borovicka J, Seibold F, Vavricka SR, Lakatos PL, Fried M, Rogler G; investigators of the Swiss Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort Study. Risk factors for complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2016;4:281-287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hasler S, Zahnd N, Müller S, Vavricka S, Rogler G, Tandjung R, Rosemann T. VAlidation of an 8-item-questionnaire predictive for a positive caLprotectin tEst and Real-life implemenTation in primary care to reduce diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease (ALERT): protocol for a prospective diagnostic study. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e007306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Blüthner E, Dehe A, Büning C, Siegmund B, Prager M, Maul J, Krannich A, Preiß J, Wiedenmann B, Rieder F, Khedraki R, Tacke F, Sturm A, Schirbel A. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel diseases in a German population. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:3465-3478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 14. | Nguyen VQ, Jiang D, Hoffman SN, Guntaka S, Mays JL, Wang A, Gomes J, Sorrentino D. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Associated Factors on Clinical Outcomes in a U.S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1825-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ghosh S, Mitchell R. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on quality of life: Results of the European Federation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2007;1:10-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 13.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Cantoro L, Monterubbianesi R, Falasco G, Camastra C, Pantanella P, Allocca M, Cosintino R, Faggiani R, Danese S, Fiorino G. The Earlier You Find, the Better You Treat: Red Flags for Early Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13:3183. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Zaharie R, Tantau A, Zaharie F, Tantau M, Gheorghe L, Gheorghe C, Gologan S, Cijevschi C, Trifan A, Dobru D, Goldis A, Constantinescu G, Iacob R, Diculescu M; IBDPROSPECT Study Group. Diagnostic Delay in Romanian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Risk Factors and Impact on the Disease Course and Need for Surgery. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:306-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yamamoto-Furusho JK, Parra-Holguín NN. Diagnostic Delay of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Is Significantly Higher in Public versus Private Health Care System in Mexican Patients. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2022;7:72-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cross E, Saunders B, Farmer AD, Prior JA. Diagnostic delay in adult inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023;42:40-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, Pittet V, Michetti P, Felley C, Mottet C, Braegger CP, Rogler D, Straumann A, Bauerfeind P, Fried M, Schoepfer AM; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:496-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Xie J, Chen M, Wang W, Shao R. Factors associated with delayed diagnosis of Crohn's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Heliyon. 2023;9:e20863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chmiel C, Vavricka SR, Hasler S, Rogler G, Zahnd N, Schiesser S, Tandjung R, Scherz N, Rosemann T, Senn O. Feasibility of an 8-item questionnaire for early diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Torres J, Halfvarson J, Rodríguez-Lago I, Hedin CRH, Jess T, Dubinsky M, Croitoru K, Colombel JF. Results of the Seventh Scientific Workshop of ECCO: Precision Medicine in IBD-Prediction and Prevention of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15:1443-1454. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Aldars-García L, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Systematic Review: The Gut Microbiome and Its Potential Clinical Application in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Microorganisms. 2021;9:977. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |