Published online Feb 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.99913

Revised: October 25, 2024

Accepted: December 5, 2024

Published online: February 7, 2025

Processing time: 149 Days and 19.3 Hours

The human gut microbiota, a complex and diverse community of microorganisms, plays a crucial role in maintaining overall health by influencing various physio

Core Tip: The human gut microbiota, a complex and diverse community of microorganisms, plays a critical role in maintaining health by influencing digestion, immune function, and disease susceptibility. Dysbiosis, an imbalance in this microbial community, is linked to conditions such as metabolic disorders, autoimmune diseases, and cancers. Key genera, including Enterococcus, Ruminococcus, and Bacteroides, are essential for immune regulation and metabolic health. Microbiota-based therapies, including probiotics and fecal microbiota transplantation, offer the potential to restore balance and improve health outcomes. We herein discuss the intimate correlations between gut microbiota and human health, predominantly associated with function, regulation, and management strategies.

- Citation: Paul JK, Azmal M, Haque ASNB, Meem M, Talukder OF, Ghosh A. Unlocking the secrets of the human gut microbiota: Comprehensive review on its role in different diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(5): 99913

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i5/99913.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i5.99913

The human gastrointestinal tract harbors a complex ecosystem of microorganisms, inclusively known as the gut microbiota. This microbial community, dominated by bacteria but also viruses, fungi, and archaea, profoundly influences host physiology, metabolism, and vulnerable function[1]. They play a pivotal part in maintaining gut barrier integrity and regulating vulnerable responses, impacting immune system development and function[2]. The human gastrointestinal tract harbors an essential ecosystem of bacteria that profoundly impacts health and disease susceptibility. Enterococcus, Ruminococcus, Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, Prevotella, Escherichia coli (E. coli), Akkermansia muciniphila, Firmicutes (including Clostridium and Lactobacillus), and Roseburia are important genera that support vulnerable regulation and metabolic processes, which are essential for gut health and general well-being[3]. It is important to recognize that other bacteria, such as Clostridioides difficile, Salmonella, Helicobacter pylori, and Fusobacterium nucleatum, are also involved in various diseases. Dysbiosis of the gut microbiota is implicated in a spectrum of diseases ranging from metabolic disorders such as obesity and diabetes, to autoimmune conditions and cancers, emphasizing their profound impact on overall health[4]. Certain gut bacteria, such as E. coli, O157 and Bacteroides fragilis produce toxins, Fusobacterium nucleatum is involved in colorectal cancer, Helicobacter pylori in gastric cancer, and Prevotella in seditious bowel complaints, contributes to inflammation and cancer progression by damaging skin and dismembering host vulnerable responses[5]. These bacteria demonstrate the intricate relationship between gut microbiota composition and disease development, emphasizing the need for targeted interventions in disease forestallment and treatment strategies[6].

The composition and diversity of the gut microbiota are influenced by various factors such as diet, lifestyle, genetics, and environmental exposures[7]. The link between gut microbiota dysbiosis and disease development has prompted ferocious exploration into understanding microbial species and their relations with the host. Understanding the gut microbiota’s role in health and disease is an area of intense scientific interest, with implications for developing novel therapeutic strategies[8]. Researchers are investigating how alterations in the gut microbiota contribute to these conditions and exploring ways to restore a healthy microbial balance[9]. The gut microbiota interacts with the host immune system, influencing immune development and responses. They can also produce metabolites that can affect host physiology, highlighting the intricate crosstalk between the gut microbiota and the host[10].

To delve deeper into the composition and function of the gut microbiota, advanced sequencing technologies and computational tools are paving a better understanding[11]. As the field of gut microbiota research continues to evolve, there is a growing interest in developing microbiota-based therapies, such as probiotics, prebiotics, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), and microbiota engineering[12]. These approaches hold promise to prevent and treat diseases by modulating gut microbiota. However, challenges remain in understanding the complex interactions between the gut microbiota and the host, as well as in developing safe and effective microbiota-based interventions[13]. The influence of gut bacteria on carcinogenesis is of particular interest, both within the gastrointestinal tract and on distant organs. Studies have linked microbial signatures associated with increased cancer threat, mechanisms by which gut bacteria modulate inflammation, and vulnerable responses[14]. This comprehensive review aims to explore the current understanding of human gut microbiota in association with disease and cancer development. It summarizes crucial findings from epidemiological studies, mechanistic exploration, and clinical observations to interpret the complex interplay between microbial communities and host health. By addressing gaps in knowledge and proposing future exploration, this review seeks to contribute to the broader issue of employing microbiota-based therapies for disease prevention and treatment.

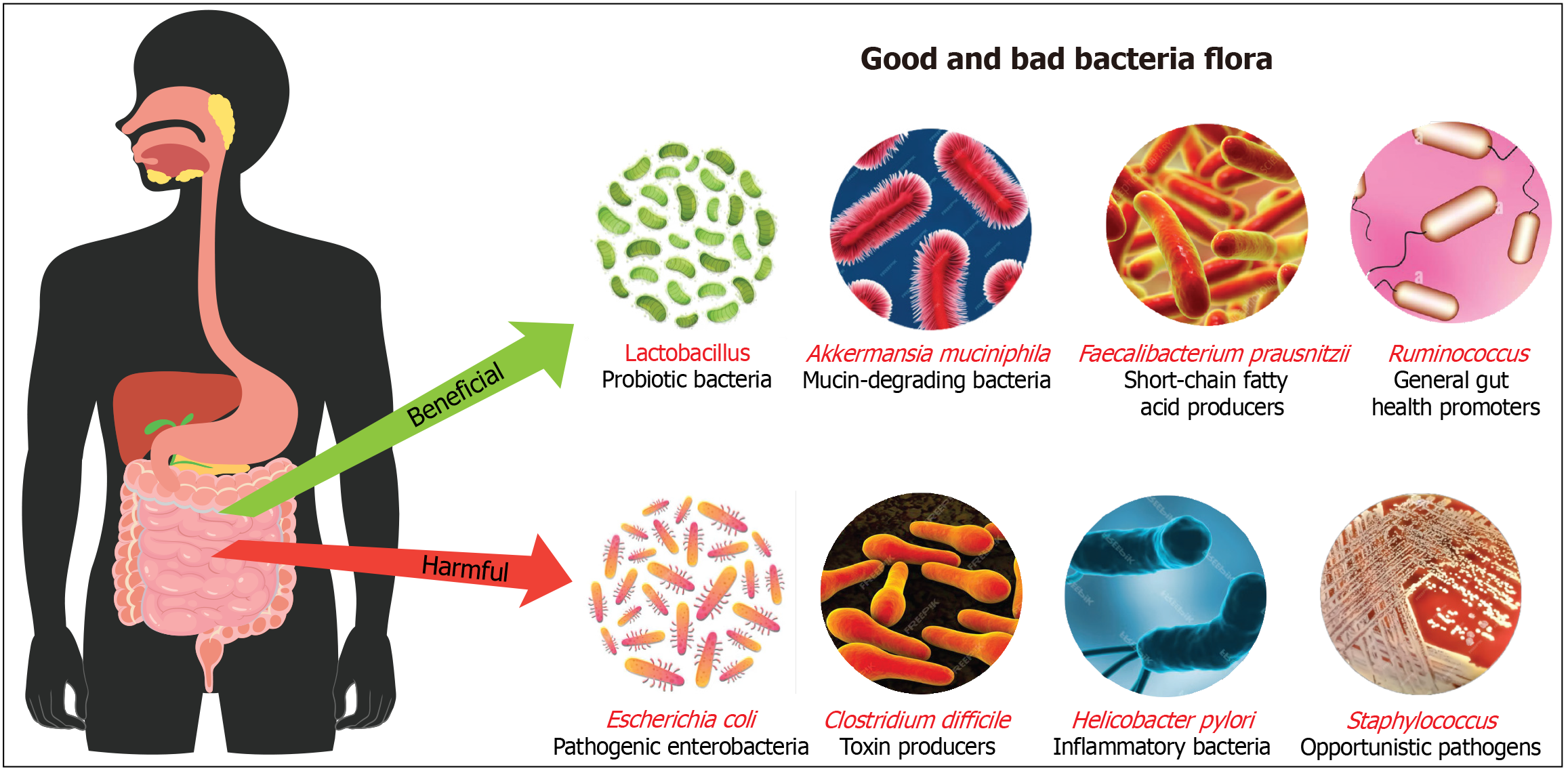

The human gut microbiota consists of different bacteria essential for digestion, metabolism, and immune function. Beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus aid in carbohydrate breakdown, vitamin production, and immune support[15]. Bifidobacterium, for instance, plays a crucial role in digesting dietary fiber and producing short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, which provide energy to gut cells and help maintain a healthy gut environment[16]. Lactobacillus is known for its ability to ferment lactose into lactic acid, aiding in lactose digestion and preventing the growth of harmful pathogens by lowering the pH of the gut[17]. Lactobacillus species also produce antimicrobial substances such as bacteriocins, which inhibit the growth of harmful bacteria, contributing to a balanced gut microbiome. Moreover, these bacteria are involved in the production of bioactive peptides that can modulate the immune system and reduce inflammation[18]. Akkermansia muciniphila maintains gut barrier integrity by degrading mucin, the main component of mucus, which fortifies the gut lining and prevents pathogens from invading the gut wall. This bacterium has been linked to metabolic health, with studies showing its association with reduced inflammation, improved glucose metabolism, and protection against obesity and diabetes. The ability of Akkermansia to interact with the host’s immune system and promote the production of anti-inflammatory molecules highlights its therapeutic potential[19]. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii produces anti-inflammatory butyrate, a SCFA that nourishes colon cells, reduces inflammation, and enhances gut barrier function, playing a significant role in preventing conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). This bacterium is one of the most abundant and important in the human gut, contributing to overall gut health by modulating immune responses and promoting a balanced inflammatory environment. Low levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii have been associated with various inflammatory conditions, making it a key target for probiotic and dietary interventions[20].

In contrast, harmful bacteria such as pathogenic E. coli and Clostridium difficile produce toxins causing gut damage and severe illnesses like diarrhea. Pathogenic E. coli strains can produce Shiga toxin, leading to bloody diarrhea and poten

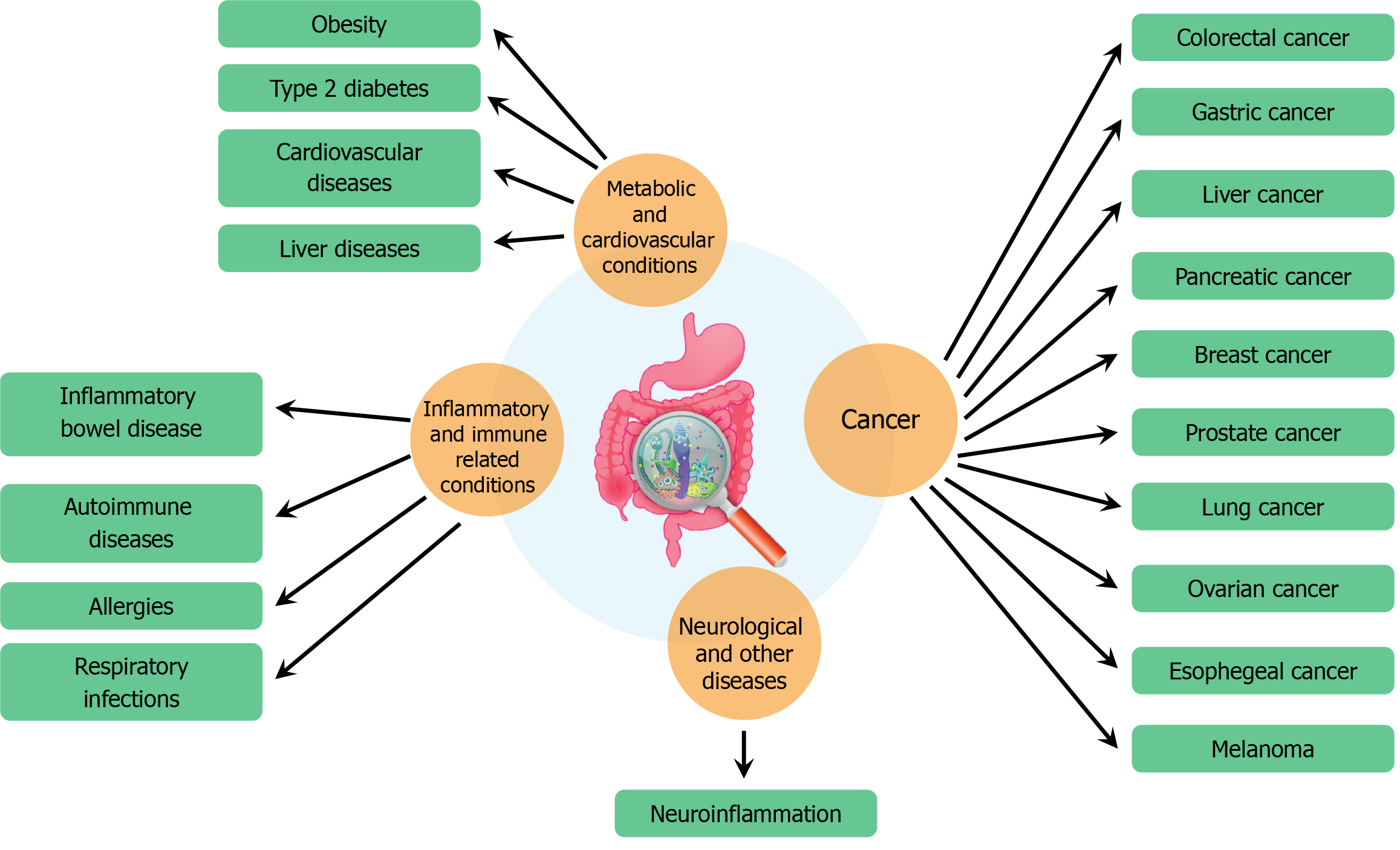

Human gut microbiota, a complex community of trillions of microorganisms residing in our intestines, has garnered significant attention due to its profound impact on various aspects of health and disease. This intricate microbial ecosystem influences a range of physiological processes, from digestion and metabolism to immune system function and even brain health. Recent research has elucidated the role of gut microbiota in numerous diseases, highlighting its potential as a therapeutic target and its significance in maintaining overall health (Figure 2).

One of the most fascinating areas of research is the gut-brain axis, which refers to the bidirectional communication between the gut microbiota and the brain. This connection is mediated through neural, endocrine, and immune pathways. Studies have shown that alterations in gut microbiota composition can influence brain function and behavior, potentially contributing to mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and autism spectrum disorders[27]. Certain gut bacteria can produce neurotransmitters like serotonin and γ-aminobutyric acid, which are crucial for regulating mood and anxiety levels[28]. Moreover, microbial metabolites such as SCFAs can affect the brain by modulating inflammation and the integrity of the blood-brain barrier[29]. Associations between gut microbiota composition and emotion-related brain functions suggest potential links to anxiety and depression, with regions such as the insula and amygdala - key players in emotional processing - frequently connected to microbial diversity[30]. A recent review underscores the significant association between gut microbiota and brain connectivity, with specific genera such as Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Ruminococcus consistently linked to brain networks like the default mode network and frontoparietal network[31]. These findings underscore the therapeutic potential of targeting gut microbiota to alleviate symptoms of mental health disorders. This evolving understanding suggests that probiotic and prebiotic treatments, alongside dietary modifications, could offer new avenues for managing and treating mental health conditions, thus integrating mental health care with dietary and microbiota-based strategies (Table 1)[32-44].

| Sl No. | Disease | Mechanism of involvement | Key bacteria implicated | Ref. |

| 1 | Alzheimer’s disease | Gut microbiota influences neuroinflammation and cognitive function; modulation of SCFA production affects brain health | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp. | [32] |

| 2 | Anxiety and depression | Dysbiosis, inflammation, cytokine release, HPA axis dysregulation | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus | [33] |

| 3 | Anxiety disorders | Gut microbiota-induced alterations in neurotransmitter levels and stress response pathways; modulation of vagus nerve activity | Campylobacter jejuni, Lactobacillus rhamnosus | [34] |

| 4 | Autism spectrum disorders | Interaction between Candida albicans and bacterial metabolites | Candida albicans | [35] |

| Changes in gut microbiota affecting neurodevelopment and behavior; disruption in SCFA metabolism affecting microglial function | Bacteroides spp., Firmicutes spp. | [36] | ||

| 5 | Cognitive impairment | Gut microbiota affecting cognitive control and executive function networks such as the FPN and DMN | Bacteroides, Prevotella, Ruminococcus | [37] |

| 6 | Depression | Dysbiosis leading to increased intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation; alterations in serotonin and other neurotransmitter levels | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp. | [38] |

| Chronic low-grade inflammation and altered neuroplasticity; influence on HPA axis and neurotransmitter metabolism | Lactobacillus spp., Bifidobacterium spp. | [39] | ||

| 7 | Emotional and interoceptive awareness | Gut microbiota composition associated with brain areas involved in emotional and visceral interoception | Roseburia, Bacteroides | [40] |

| 8 | Irritable bowel disease | Disruption in the balance of gut microbiota leads to chronic inflammation and dysbiosis affecting mood and stress responses | Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Bacteroides spp. | [41] |

| 9 | Irritable bowel syndrome | Gut microbiota-induced inflammation and dysregulation of the enteric nervous system; alterations in gut motility and visceral hypersensitivity | Bifidobacterium spp., Lactobacillus spp. | [42] |

| 10 | Mood disorders | Alterations in gut-brain communication affecting mood-related brain networks | Bifidobacterium, Collinsella | [43] |

| 11 | Neurological disorders | Influence on neuroinflammation, gut-brain axis communication | Lactobacillus, Bacteroides | [44] |

The gut microbiota plays a critical role in the development and modulation of the immune system. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the gut microbial community, has been implicated in various autoimmune diseases, where the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks its own tissues[45]. Conditions like rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, and IBD have been linked to alterations in gut microbiota[46]. Studies have shown that certain pathogenic bacteria can trigger inflammatory responses, while beneficial microbes can help to maintain immune tolerance[47]. This delicate balance is essential for preventing autoimmune reactions. Understanding the specific microbial changes associated with these diseases can lead to new strategies for prevention and treatment[48]. This line of research opens promising avenues for using microbiota modulation as a form of immunotherapy, offering hope for better management of autoimmune diseases through non-invasive and dietary-based approaches (Table 2)[49-61].

| Sl No. | Disease | Mechanism of involvement | Key bacteria implicated | Ref. |

| 1 | Allergies | Modulation of immune responses, allergic inflammation | Clostridium, Bifidobacterium | [49] |

| 2 | Autoimmune diseases | Dysregulated immune responses, inflammation | Prevotella, Bacteroides | [50] |

| 3 | Cardiovascular diseases | Production of trimethylamine N-oxide, systemic inflammation | Prevotella, Firmicutes | [51] |

| 4 | Inflammatory bowel disease | Dysregulated immune responses against microbiota lead to chronic inflammation in the GI tract. Reduced anti-inflammatory microbes and increased potentially inflammatory microbes. SCFAs and dietary factors influence disease progression | Decreased Bacteroidetes, Lachnospiraceae, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Increased Proteobacteria, Ruminococcus gnavus. Key producers: Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Roseburia hominis. Pathogens: Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus | [52] |

| Associated with reduced anti-inflammatory response. Increased pro-inflammatory activity | Reduced abundance of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii. Overgrowth of Escherichia coli | [53] | ||

| 5 | Liver diseases | Regulation of bile acid metabolism, inflammation | Enterococcus, Ruminococcus | [54] |

| 6 | Multiple sclerosis | Microbiota interaction: Dysbiosis with increased Euryarchaeota and Verrucomicrobia. Microbial impact: Modulation of T cell responses and inflammation in the central nervous system. Protective effects: Certain bacteria and metabolites have protective effects against disease | Increased: Methanobrevibacter smithii, Akkermansia muciniphila. Decreased: Clostridia clusters XIVa and IV, Bacteroidetes. Protective: Lactobacillus reuteri, Lactobacillus murinus | [55] |

| Akkermansia muciniphila and Acinetobacter calcoaceticus induce pro-inflammatory responses. Parabacteroides distasonis stimulates anti-inflammatory Tregs | Decreased abundance of Lachnospiraceae and Faecalibacterium. Increased abundance of Akkermansia spp. | [56] | ||

| 7 | Respiratory infections | Modulation of respiratory immune responses, inflammation | Streptococcus, Haemophilus | [57] |

| 8 | Rheumatoid arthritis | Dysbiosis contributes to systemic inflammation and joint symptoms; gut barrier dysfunction affecting overall immune response | Prevotella spp., Fusobacterium spp. | [58] |

| Microbiota interaction: Oral and intestinal dysbiosis linked to disease severity and immune responses. Microbiota influence: Microbial DNA and peptidoglycan-polysaccharide complexes found in joints. Microbial-induced immunity: Certain bacteria drive inflammation through immune cell activation | Oral dysbiosis: Porphyromonas gingivalis, Lactobacillus salivarius. Intestinal dysbiosis: Increased Gram-positive bacteria, Prevotella copri. Exacerbation: Prevotella copri, Segmented filamentous bacteria | [59] | ||

| Pro-inflammatory molecule production. Autoreactive immune cell activation. Linked to RA susceptibility with specific HLA-DRB1 alleles | Overgrowth of Prevotella spp., reduction in Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, butyrate-producing bacteria, and high abundance of Ruminococcus gnavus | [60] | ||

| 9 | Systemic lupus erythematosus | Microbiota interaction: Dysbiosis in oral and gut microbiota contributes to disease through molecular mimicry and bacterial antigen recognition. Metabolic factors: Bacterial metabolites impact disease severity | Increased: Lactobacillaceae, Ruminococcus gnavus. Decreased: Bifidobacteria, Clostridiales. Specific antigens: Propionibacterium propionicum, Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | [61] |

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is another condition where gut microbiota has been shown to play a significant role. Individuals with T2D often exhibit distinct gut microbiota profiles compared to healthy individuals[62]. Dysbiosis in T2D is characterized by a reduced diversity of gut bacteria and an increase in opportunistic pathogens[63]. These microbial changes can influence glucose metabolism, insulin resistance, and chronic inflammation, all of which are key factors in the development and progression of diabetes[64]. Certain gut bacteria can affect the production of SCFAs, which in turn influence insulin sensitivity[65]. Moreover, the gut microbiota can interact with dietary components to modulate the host’s metabolic response. These insights highlight the potential of manipulating gut microbiota through diet, probiotics, or other interventions as an approach to diabetes management[66]. Future therapeutic strategies could involve personalized nutrition plans and microbiota-based treatments to improve insulin sensitivity and metabolic health, providing a more tailored approach to diabetes management (Table 3)[67-82].

| Sl No. | Disease/drug target | Mechanism of involvement | Key bacteria or drug implicated | Ref. |

| 1 | GLP-1 receptor agonists | Mimic the incretin GLP-1, enhancing insulin secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and altering gut microbiota composition | Decreased: Allobaculum, Turicibacter, Anaerostipes, Blautia, Lactobacillus, Butyricimonas, Desulfovibrio, Clostridiales, Bacteroidales. Increases: Akkermansia muciniphila | [67] |

| 2 | Insulin | Improves glycemic control by increasing glucose uptake into cells. Minimal direct impact on gut microbiota | Minimal direct effect on humans. In rats, it increased Norank_f_Bacteroidales_S24-7 and decreased Lactobacillus and Peptostreptococcaceae, suggesting possible effects on gut bacteria in animal models. Effect on T2DM: Influences microbiota dysbiosis in T2DM patients, potentially regulating inflammation and gut health | [68] |

| 3 | Metabolic syndrome | Increased intestinal permeability leading to systemic inflammation; effects on metabolic pathways and mood | Increased: Lactobacillus spp., Bacteroides spp. | [69] |

| 4 | Obesity | Gut microbiota affecting metabolic processes and inflammatory responses; alterations in appetite regulation and mood | Increased: Firmicutes spp., decreased: Bacteroidetes spp. | [70] |

| Metabolic dysregulation, energy extraction from diet | Increased: Bacteroides, Firmicutes | [71] | ||

| 5 | SGLT2 inhibitors | Inhibit SGLT2 in the proximal tubule, preventing glucose reabsorption and promoting glucose excretion in urine. Limited impact on gut microbiota reported | Dapagliflozin is used as drug. Ruminococcaceae, Proteobacteria (Desulfovibrionaceae); Sotagliflozin changes in Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio with high-sucrose diet | [72] |

| 6 | Type 1 diabetes | Altered microbiota composition influencing the immune system and glucose metabolism | Decrease: Prevotella, Akkermansia. Increase: Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Lactobacillus, Lactococcus, Bifidobacterium, Streptococcus | [73] |

| Increased abundance of certain bacteria linked to inflammation and immune responses. Decreased abundance of beneficial bacteria | Increase: Clostridium, Bacteroides, Veillonella. Decrease: Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Blautia coccoides/Eubacterium rectale, Prevotella | [74] | ||

| Insulin resistance, inflammation | Decreased: Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium | [75] | ||

| Microbial composition influences immune responses and disease onset | Decreased: Bifidobacteria, Lachnospiracea | [76] | ||

| 7 | Type 2 diabetes mellitus | Changes in bile acid metabolism affecting glucose metabolism | Involvement of Clostridium, Eubacterium, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium | [77] |

| Correlation between gut microbiota composition and inflammatory markers influencing diabetes progression | Increased: Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria. Decreased: Roseburia, Firmicutes, Clostridiaceae | [78] | ||

| Imbalance in microbiota affecting glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity | Decrease: Firmicutes. Increase: Bacteroidetes, Proteobacteria, Lactobacillus, Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Blautia, Serratia | [79] | ||

| Increased abundance of certain bacteria linked to metabolic dysfunction and inflammation | Increase: Faecalibacterium prausnitzii, Blautia. Decrease: Verrucomicrobia phylum | [80] | ||

| Influence of SCFA production on insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism | Increase: Bacteroides, Ruminococcus, Akkermansia muciniphila. Decrease: Roseburia, Clostridium | [81] | ||

| Inhibit the enzyme DPP-4, which prolongs the action of incretins (e.g., GLP-1), enhancing insulin secretion and reducing glucose levels. Effects on microbiota include changes in diversity and composition | Sitagliptin and Blautia used as drug. Blautia increases, while changes in Roseburia, Clostridium, Bacteroides, Erysipelotrichaceae, and Firmicutes are variable and require more research | [82] |

The role of gut microbiota in cancer progression is a dynamic and multifaceted area of exploration that continues to evolve. Dysbiosis is implicated in various conditions, including metabolic diseases such as obesity and diabetes, where altered microbial metabolism affects host energy balance and systemic inflammation[83]. Specific microbial taxa and their metabolites have been linked to cancer initiation and progression, especially in colorectal cancer, through mechanisms involving inflammation, genotoxicity, and modulation of tumor microenvironments[84]. Certain bacterial species have been found to promote colorectal cancer by producing toxins that damage DNA or by inducing chronic inflammation[85]. Conversely, other microbes may have protective effects by enhancing immune surveillance and inhibiting tumor growth. Gut microbiota can affect the efficacy and toxicity of cancer treatments, such as chemotherapy and immunotherapy[86]. Personalized modulation of the gut microbiome could therefore represent a promising strategy for impro

| Sl No. | Disease | Mechanism of involvement | Key bacteria implicated | Ref. |

| 1 | Breast cancer | Modulation of systemic inflammation, hormone metabolism | Lactobacillus, Prevotella | [88] |

| Gut microbiota impacts hormone levels and immune responses. Microbiota may modulate estrogen levels and immune cell infiltration in breast tissue, affecting cancer risk and progression | Clostridium, Bifidobacterium | [89] | ||

| 2 | Colorectal cancer | Chronic inflammation, carcinogen metabolism | Fusobacterium nucleatum, Escherichia coli | [90] |

| Gut microbiota influences chemotherapy efficacy. Microbial dysbiosis can affect drug metabolism and immune responses, altering treatment outcomes | Fusobacterium nucleatum, Bacteroides | [91] | ||

| 3 | Esophageal cancer | Dysbiosis in esophageal microbiome, inflammatory pathways | Prevotella, Fusobacterium | [92] |

| Dysbiosis in esophageal microbiota is associated with cancer. Microbial-induced inflammation and changes in the esophageal microenvironment can contribute to cancer development | Prevotella, Streptococcus | [93] | ||

| 4 | Gastric cancer | Disruption of gastric mucosa, inflammation | Helicobacter pylori | [94] |

| Helicobacter pylori is a major risk factor for gastric cancer. Chronic infection with Helicobacter pylori causes inflammation and genetic alterations leading to cancer | Helicobacter pylori | [95] | ||

| 5 | Liver cancer | Modulation of liver inflammation, bile acid metabolism | Enterococcus, Bacteroides | [96] |

| Gut microbiota can contribute to liver cancer development. Microbiota produced metabolites and inflammation can promote liver cancer progression | Enterococcus faecalis, Bacteroides | [97] | ||

| 6 | Lung cancer | Impact on lung microbiome, immune response modulation | Streptococcus, Bacteroides | [98] |

| Oral and gut microbiota are linked to lung cancer risk. Inhaled microbiota or systemic effects from gut microbiota can influence lung inflammation and carcinogenesis | Streptococcus, Veillonella | [99] | ||

| 7 | Melanoma | Systemic immune modulation, tumor microenvironment | Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus | [100] |

| 8 | Ovarian cancer | Role in local inflammation, metabolic influences | Ruminococcus, Clostridium | [101] |

| 9 | Pancreatic cancer | Alteration of pancreatic microenvironment, immune modulation | Akkermansia muciniphila, Bifidobacterium | [102] |

| Microbiota composition affects pancreatic cancer development. Specific bacteria may modulate inflammation and immune responses in the pancreas | Porphyromonas gingivalis, Fusobacterium nucleatum | [103] | ||

| 10 | Prostate cancer | Influence on androgen metabolism, immune modulation | Clostridium, Firmicutes | [104] |

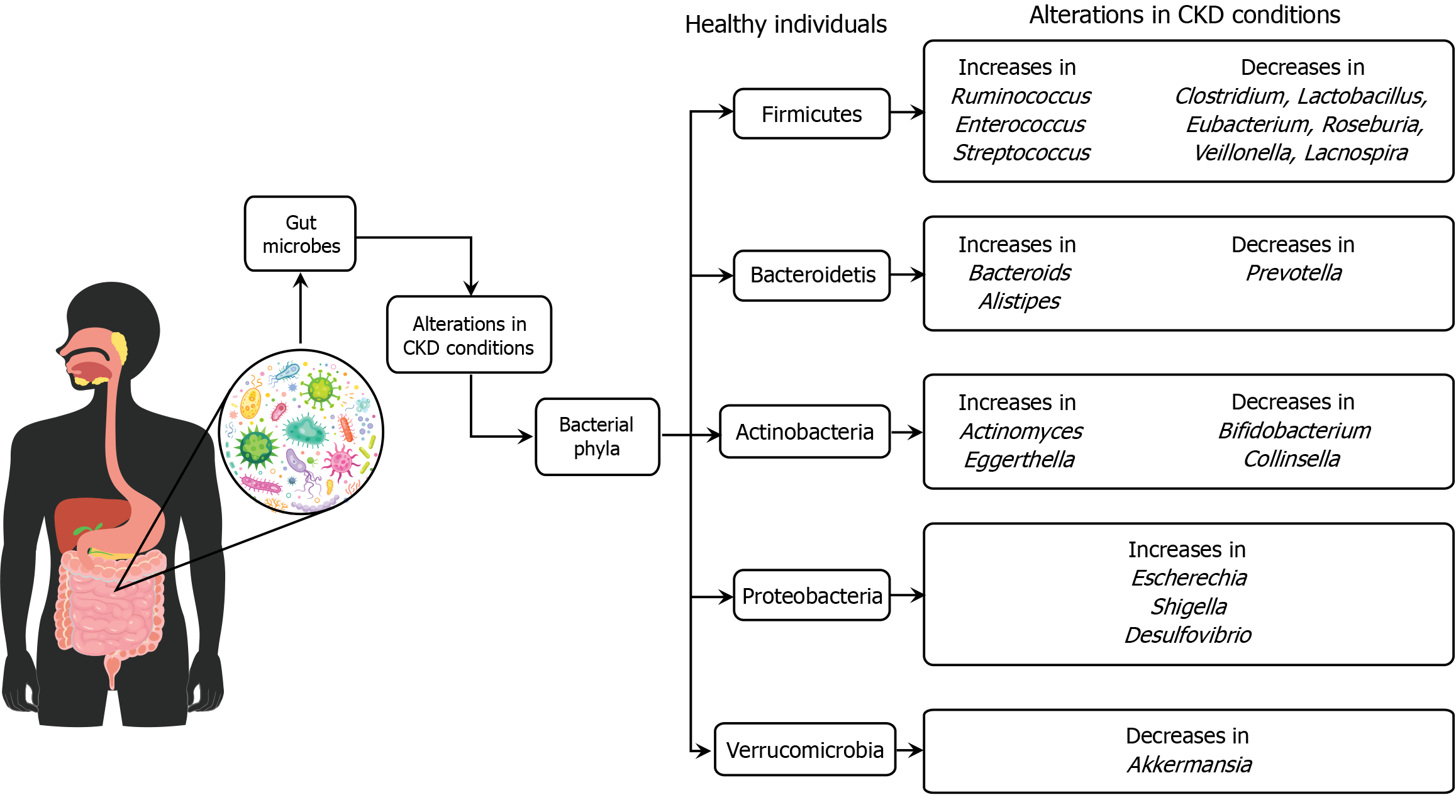

The gut microbiota plays a crucial role in the development and progression of chronic kidney disease (CKD). It comprises trillions of microorganisms that influence various physiological processes, including metabolism, immune function, and inflammation[105]. In CKD, the composition and diversity of gut microbiota are often altered, leading to dysbiosis, which exacerbates the disease[106]. This dysbiosis can result in the overproduction of uremic toxins, which accumulate in the blood due to impaired renal function and contribute to inflammation and further kidney damage[107]. Additionally, changes in diet and medication use in CKD patients can further impact the gut microbiome, highlighting the potential for dietary interventions and probiotics to restore microbial balance and potentially slow CKD progression[108]. Understanding the complex interactions between the gut microbiota and CKD could lead to novel therapeutic approaches for managing the disease and improving patient outcomes (Figure 3).

A recent study explored the relationship between gut microbiota and CKD, revealing a significant reduction in microbial diversity in CKD patients compared to healthy individuals[109]. This reduction is linked with inflammation and metabolic alterations typical of CKD. The study highlights specific bacterial genera, such as Bacteroides and Prevotella, that are associated with inflammatory markers and metabolic imbalances. It emphasizes the role of dietary intake in influencing gut microbiota composition and suggests that nutritional interventions could modulate gut microbiota to potentially alleviate CKD symptoms. The findings propose that targeting gut microbiota through dietary modifications or probiotic treatments could be a promising therapeutic strategy for managing CKD, advocating for further research to understand the underlying mechanisms and develop effective interventions.

Another study found significant alterations in gut microbiota composition and diversity in CKD patients compared to healthy controls, with an increase in Proteobacteria and a decrease in synergies, especially in advanced stages[110]. Specific bacterial genera, such as Escherichia-Shigella, were identified as potential biomarkers for distinguishing CKD patients from healthy individuals. Functional analysis indicated enriched metabolic pathways related to fatty acid and inositol phosphate in CKD, while amino acid and oxidative phosphorylation pathways were more active in healthy controls. These microbiota changes could aid in early CKD diagnosis and monitoring[111].

There is a consistent alteration in the gut microbiota composition in patients with CKD, marked by a decrease in beneficial bacteria like Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus and an increase in potentially harmful bacteria such as Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcus[112]. Dysbiosis in CKD patients is associated with increased production of uremic toxins, such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate, which are linked to the progression of kidney disease and cardiovascular complications. Dietary interventions, probiotics, and prebiotics show potential in modulating gut microbiota composition, reducing uremic toxins, and improving CKD outcomes, although more clinical trials are needed to confirm these effects[113].

A recent systematic review indicated that patients with CKD exhibit distinct changes in their gut microbiota composition, characterized by a decrease in beneficial bacteria such as Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, and an increase in pathogenic bacteria like Enterobacteriaceae and E. coli. These alterations are associated with CKD progression and systemic inflammation, suggesting a potential link between gut microbiota dysbiosis and CKD pathophysiology. Additionally, interventions targeting gut microbiota, such as probiotics and prebiotics, have shown promise in modulating these microbial imbalances and improving CKD outcomes[114]. However, the findings across studies are often inconsistent and lack replication, with variations in methodologies and target populations complicating the ability to draw definitive conclusions about microbiota-connectivity associations across different diseases.

This underscores the complexity of gut-brain interactions and the need for more standardized research approaches to better understand these relationships[115]. Another recent original study identified significant differences in gut microbiota diversity and composition between stage 4 and 5 CKD patients and healthy controls[116]. Patients with stage 4 and 5 CKD exhibited lower species richness and diversity, with a notable reduction in beneficial bacteria such as Faecalibacterium and Roseburia and an increase in potential pathogens like Escherichia-Shigella. Alpha and beta diversity analyses confirmed these disparities, highlighting a strong correlation between gut microbiota alterations and CKD severity[116].

Linear discriminant analysis effect size analysis revealed distinct microbial and metabolic pathway profiles between the two groups, suggesting that these microbial changes could have functional implications in CKD progression[17]. A study in end-stage renal disease patients from southern China found a reduction in total gut bacteria. Beneficial butyrate-producing bacteria (Roseburia, Faecalibacterium, and Prevotella) were reduced in end-stage renal disease patients, while Bacteroides were more prevalent. These changes were associated with increased inflammation and worsened renal function, as indicated by markers like cystatin C and estimated glomerular filtration rate, suggesting that gut microbiota alterations may play a role in CKD progression[117].

Therapeutic strategies targeting the gut microbiota encompass a range of approaches aimed at restoring microbial balance and improving host health. Probiotics, live microorganisms that benefit health by colonizing the gut, are widely used to restore diversity post-antibiotic therapy and support gut health. Prebiotics, non-digestible fibers that promote beneficial bacteria growth, play a crucial role in reducing inflammation, particularly in conditions like IBD. FMT is highly effective in treating Clostridium difficile infections by restoring microbial diversity. Dietary modifications, such as high-fiber or Mediterranean diets, manage symptoms in conditions like irritable bowel syndrome. Postbiotics, metabolites produced by probiotics, are studied for their therapeutic potential in metabolic disorders. Antibiotics are used cautiously to avoid disrupting beneficial microbes. Phage therapy targets harmful bacteria, offering an alternative to antibiotics (Figure 4). Microbial ecosystem therapeutics engineer microbial communities to enhance gut health and treat inflammatory diseases, highlighting personalized microbiota-based therapies in disease prevention and treatment (Table 5)[118-137].

| Sl No. | Therapeutic strategy | Description | Clinical application | Ref. |

| 1 | Antibiotics | Targeted use to treat dysbiosis or specific bacterial infections affecting gut health | Used in severe cases of gut dysbiosis | [118] |

| 2 | Biofilm disruptors | Compounds that disrupt bacterial biofilms in the gut, enhancing susceptibility to treatment | Investigated for their potential in chronic infection treatments | [119] |

| 3 | Butyrate supplementation | Providing the short-chain fatty acid butyrate to support gut barrier function and reduce inflammation | Studied for efficacy in treating ulcerative colitis | [120] |

| 4 | Colonization resistance | Strategies to enhance the gut’s ability to resist colonization by harmful bacteria | Investigated in preventing infections in hospitalized patients | [121] |

| 5 | Dietary modifications | Including high-fiber diets, Mediterranean diet, and low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols diet to support gut microbiota | Management of symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome | [122] |

| 6 | Enteral nutrition | Providing nutrients directly into the gastrointestinal tract to support gut health | Used in patients unable to tolerate oral intake | [123] |

| 7 | Fecal microbiota transplantation | Transfer of fecal microbiota from a healthy donor to restore microbial diversity in the recipient | Effective treatment for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection | [124] |

| 8 | Gut microbiota modulators | Pharmaceuticals that target specific pathways or microbes within the gut | Studied for their potential in precision medicine approaches | [125] |

| 9 | Microbial consortia therapy | Using multiple species of bacteria to restore healthy microbial balance | Investigated in treating recurrent bacterial infections | [126] |

| 10 | Microbial ecosystem therapeutics | Engineered microbial communities designed to restore or enhance gut health | Investigated for potential in treating inflammatory diseases | [127] |

| 11 | Microbiota-targeted dietary interventions | Specific diets aimed at altering the composition and function of gut microbes | Used in managing metabolic syndrome and obesity | [128] |

| 12 | Phage therapy | Using bacteriophages to selectively target harmful bacteria in the gut microbiota | Potential alternative to antibiotics in treating infections | [129] |

| 13 | Postbiotics | Metabolites produced by probiotic bacteria have beneficial effects on host health | Investigated for potential in treating metabolic disorders | [130] |

| 14 | Prebiotics | Non-digestible fibers that promote the growth of beneficial bacteria in the gut | Improve gut health and reduce inflammation in IBD patients | [131] |

| 15 | Probiotics | Live microorganisms that confer health benefits by colonizing the gut and influencing microbial balance | Used to restore gut microbiota after antibiotic therapy | [132] |

| 16 | Protein therapeutics | Engineered proteins designed to modulate microbial activity in the gut | Investigated for their role in targeted microbiota treatments | [133] |

| 17 | Proton pump inhibitors | Medications that alter gastric acidity and impact gut microbiota composition | Used to manage symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease | [134] |

| 18 | Stool substitutes | Synthetic or cultured microbial communities for fecal microbiota transplantation when donor stool is unavailable or impractical | Investigated as a potential treatment for chronic infections | [135] |

| 19 | Symbiotics | Combination of probiotics and prebiotics to enhance gut health | Used in enhancing gut health and immune function | [136] |

| Studied for efficacy in treating diarrhea in children | [137] |

Antibiotics and other medications can significantly impact the composition and function of gut microbiota, leading to various health consequences. The use of antibiotics, while essential for treating bacterial infections, often results in the disruption of the gut microbiome’s balance, causing a reduction in microbial diversity and the proliferation of resistant strains[138]. This disruption can have short-term and long-term effects on health, including increased susceptibility to infections, antibiotic-associated diarrhea, and the potential for developing chronic conditions such as IBD and obesity[139].

Other medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), and antipsychotics, also influence gut microbiota. NSAIDs, for example, can cause intestinal inflammation and mucosal damage, which in turn alters the gut microbiota composition[140]. PPIs, commonly used to treat acid reflux, have been shown to decrease microbial diversity and promote the growth of potentially harmful bacteria, such as Enterococcus and Streptococcus species[141]. Antipsychotic medications have been linked to changes in gut microbiota that may contribute to metabolic side effects, including weight gain and insulin resistance[142]. The interactions between medications and gut microbiota are complex and influenced by multiple factors, including the type of medication, dosage, duration of treatment, and individual patient characteristics[143]. Understanding these interactions is crucial for developing strategies to mitigate negative effects on the gut microbiome and enhance overall health outcomes.

The impact of antibiotics and medications on gut microbiota and disease is increasingly clear, with antibiotic use significantly altering microbiota composition. This disruption can lead to conditions such as antibiotic-associated diarrhea, Clostridioides difficile infection, and the development of antibiotic-resistant infections[144-146]. Recent research has highlighted the critical role of gut microbiota in influencing drug metabolism, efficacy, and safety[147]. Gut bacteria can chemically modify drugs, affecting their bioavailability and activity, with some species activating or deactivating drugs through enzymatic actions. Specific bacterial strains such as Gammaproteobacteria have been found to metabolize chemotherapy drugs like gemcitabine into inactive forms, reducing its effectiveness in cancer treatment[147]. Conversely, commensal bacteria such as Enterococcus hirae and Barnesiella intestinihominis have been shown to enhance the efficacy of other drugs like cyclophosphamide by stimulating immune responses in cancer therapies. These microbiota-related interactions offer promising potential for using specific bacterial markers as indicators of therapeutic outcomes, guiding the development of personalized treatments based on an individual’s microbiome composition[148].

Long-term antibiotic use has been linked to chronic conditions like IBD, Crohn’s disease, and metabolic syndrome by disrupting microbial balance[149,150]. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in the gut microbiota, is implicated in obesity, asthma, allergies, cardiovascular disease, and depression, where altered microbiota affect metabolism, immune function, and neurotransmitter production[151-153]. Non-antibiotic medications, such as NSAIDs and PPIs, also contribute to intestinal inflammation, dysbiosis, and conditions like ulcerative colitis, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, and lactose intolerance[154-156]. In diseases like celiac disease, CKD, and colorectal cancer, gut microbiota alterations influence inflammation, uremic toxin production, and cancer progression[157,158]. Additionally, early-life antibiotic exposure is associated with increased risks of asthma, allergies, autism spectrum disorder, eczema, and psoriasis, highlighting the critical role of gut microbiota in immune regulation and disease susceptibility across various conditions[159].

Current research on the involvement of gut microbiota in disease and cancer has several key gaps. One major challenge is the substantial variability in microbiota composition among individuals, influenced by factors such as diet, genetics, and lifestyle. This variability complicates efforts to establish clear causal relationships between specific microbial profiles and disease states. Mechanistic understanding also remains limited; while correlations exist between microbiota composition and diseases like colorectal cancer, the precise biological mechanisms underlying these associations are often unclear (Table 6)[160-171]. Many studies are cross-sectional, providing snapshots rather than longitudinal insights into how microbiota changes over time and correlate with disease progression. Addressing these gaps requires large-scale, longitudinal studies that integrate multi-omics data to elucidate microbiota-host interactions comprehensively.

| Sl No. | Aspect | Description | Ref. |

| 1 | Crosstalk with immune system | Microbiota interact with the immune system. Research should focus on how these interactions influence autoimmune diseases, allergies, and cancer | [160] |

| 2 | Impact of antibiotics and therapeutics | Antibiotics and medications alter microbiota. Understanding these effects is important for assessing long-term health consequences | [161] |

| 3 | Interaction with host genetics | Host genetics influence microbiota. Understanding these interactions is key to linking genetic predispositions with microbiota and disease risk | [162] |

| 4 | Mechanistic understanding | While correlations between microbiota and diseases exist, the mechanisms remain unclear. Future studies should explore specific microbial influences on disease | [163] |

| 5 | Microbial metabolites and signaling | Microbial metabolites affect host physiology. Identifying these metabolites and their role in disease modulation is crucial | [164] |

| 6 | Microbiota and cancer immunotherapy | Gut microbiota impact cancer immunotherapy efficacy, but mechanisms are poorly understood. Identifying beneficial microbial profiles is necessary | [165] |

| 7 | Microbiota in early life and development | Early microbiota establishment affects long-term health. Research should examine its impact on immune and metabolic development | [166] |

| 8 | Microbiota in extraintestinal diseases | Gut microbiota may influence non-gut diseases like cardiovascular and neurological disorders. Research is needed to explore these associations | [167] |

| 9 | Need for longitudinal studies | Most studies are cross-sectional; longitudinal research is needed to track microbiota changes over time in relation to disease | [168] |

| 10 | Role of diet and lifestyle | Diet and lifestyle significantly influence microbiota. Research should focus on how these factors affect microbiota and disease risk | [169] |

| 11 | Gender differences in microbiota | Gender-specific microbiota differences influence disease outcomes. Research should explore how these variations impact health between males and females | [170] |

| 12 | Variability in microbiota composition | Challenges arise due to factors like diet, genetics, and lifestyle. Research lacks comprehensive large-scale studies on these interactions | [171] |

Future research directions should focus on integrating multi-omics data to better understand the intricate interactions between gut microbiota and disease. This approach will help identify microbial biomarkers and therapeutic targets, facilitating personalized medicine strategies tailored to individual microbiota profiles. Exploring the impact of diet and lifestyle interventions on microbiota composition and disease outcomes is crucial. Investigating microbiota engineering techniques, such as precision microbiome editing and synthetic ecology, holds promise for developing novel therapies. Ethical considerations surrounding microbiota-based therapies also demand attention, including issues of informed consent, privacy protections for microbiota data, and equitable access to emerging treatments.

To advance our understanding of the role of gut microbiota in health and disease, it is crucial to integrate multi-omics data, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiomics. This comprehensive approach allows for the study of interactions between gut microbiota and disease, helping to identify microbial biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and molecular pathways that underlie disease mechanisms[172,173]. Investigating the impact of dietary patterns, prebiotics, probiotics, dietary fibers, and lifestyle factors such as exercise and stress management on gut microbiota composition and function is essential[145]. Understanding these impacts can lead to personalized dietary and lifestyle recommendations tailored to individual microbiota profiles, ultimately aiding in disease prevention and management[174,175].

The exploration of advanced microbiota engineering techniques, including precision microbiome editing, synthetic biology, and microbial ecosystem engineering, offers promising avenues for manipulating microbiota composition and function to promote health or treat diseases[176]. These innovative approaches have the potential to provide novel therapeutic interventions based on microbial modulation. Alongside these scientific advancements, it is important to address ethical considerations in microbiota-based therapies[177]. This includes ensuring informed consent for research and therapy participation, protecting privacy related to microbiota data, and ensuring equitable access to emerging treatments. Ensuring transparency, safety, and fairness in the implementation of microbiota-related interventions is crucial for maintaining ethical standards and public trust in these healthcare innovations[178].

Human gut microbiota plays a critical role in maintaining overall health, influencing various physiological processes, and modulating disease susceptibility, including cancer. The complex ecosystem of beneficial and harmful bacteria within the gut impacts digestion, immune function, and systemic health through intricate mechanisms involving microbial metabolites and interactions with the host immune system. Dysbiosis, or the disruption of this microbial balance, is implicated in a wide range of diseases, from metabolic and autoimmune disorders to various cancers. Current research has highlighted the profound impact of specific gut bacteria on disease progression and cancer development, under

The authors acknowledge the logistic support and laboratory facilities of the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, Bangladesh.

| 1. | Thursby E, Juge N. Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochem J. 2017;474:1823-1836. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1710] [Cited by in RCA: 2060] [Article Influence: 257.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 2. | Takiishi T, Fenero CIM, Câmara NOS. Intestinal barrier and gut microbiota: Shaping our immune responses throughout life. Tissue Barriers. 2017;5:e1373208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 248] [Cited by in RCA: 630] [Article Influence: 78.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Zhang YJ, Li S, Gan RY, Zhou T, Xu DP, Li HB. Impacts of gut bacteria on human health and diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:7493-7519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 599] [Article Influence: 59.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hou K, Wu ZX, Chen XY, Wang JQ, Zhang D, Xiao C, Zhu D, Koya JB, Wei L, Li J, Chen ZS. Microbiota in health and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7:135. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 1357] [Article Influence: 452.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gong D, Adomako-Bonsu AG, Wang M, Li J. Three specific gut bacteria in the occurrence and development of colorectal cancer: a concerted effort. PeerJ. 2023;11:e15777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Davoutis E, Gkiafi Z, Lykoudis PM. Bringing gut microbiota into the spotlight of clinical research and medical practice. World J Clin Cases. 2024;12:2293-2300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hasan N, Yang H. Factors affecting the composition of the gut microbiota, and its modulation. PeerJ. 2019;7:e7502. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 187] [Cited by in RCA: 442] [Article Influence: 73.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 8. | Afzaal M, Saeed F, Shah YA, Hussain M, Rabail R, Socol CT, Hassoun A, Pateiro M, Lorenzo JM, Rusu AV, Aadil RM. Human gut microbiota in health and disease: Unveiling the relationship. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:999001. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 287] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Guinane CM, Cotter PD. Role of the gut microbiota in health and chronic gastrointestinal disease: understanding a hidden metabolic organ. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2013;6:295-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 499] [Cited by in RCA: 571] [Article Influence: 47.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wiertsema SP, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Garssen J, Knippels LMJ. The Interplay between the Gut Microbiome and the Immune System in the Context of Infectious Diseases throughout Life and the Role of Nutrition in Optimizing Treatment Strategies. Nutrients. 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 223] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kwa WT, Sundarajoo S, Toh KY, Lee J. Application of emerging technologies for gut microbiome research. Singapore Med J. 2023;64:45-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Quaranta G, Guarnaccia A, Fancello G, Agrillo C, Iannarelli F, Sanguinetti M, Masucci L. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation and Other Gut Microbiota Manipulation Strategies. Microorganisms. 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Quigley EMM, Gajula P. Recent advances in modulating the microbiome. F1000Res. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Rahman MM, Islam MR, Shohag S, Ahasan MT, Sarkar N, Khan H, Hasan AM, Cavalu S, Rauf A. Microbiome in cancer: Role in carcinogenesis and impact in therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;149:112898. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kho ZY, Lal SK. The Human Gut Microbiome - A Potential Controller of Wellness and Disease. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:1835. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 451] [Cited by in RCA: 651] [Article Influence: 93.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Portincasa P, Bonfrate L, Vacca M, De Angelis M, Farella I, Lanza E, Khalil M, Wang DQ, Sperandio M, Di Ciaula A. Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 515] [Cited by in RCA: 471] [Article Influence: 157.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kim HN, Kim JH, Chang Y, Yang D, Joo KJ, Cho YS, Park HJ, Kim HL, Ryu S. Gut microbiota and the prevalence and incidence of renal stones. Sci Rep. 2022;12:3732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Dunlap AS, Papaj DR, Dornhaus A. Sampling and tracking a changing environment: persistence and reward in the foraging decisions of bumblebees. Interface Focus. 2017;7:20160149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Beaulé PE, Roffey DM, Poitras S. [Amélioration continue de la qualité en chirurgie orthopédique: modifications et répercussions de la réforme du financement du système de santé]. Can J Surg. 2016;59:151-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Yang M, Wang JH, Shin JH, Lee D, Lee SN, Seo JG, Shin JH, Nam YD, Kim H, Sun X. Pharmaceutical efficacy of novel human-origin Faecalibacterium prausnitzii strains on high-fat-diet-induced obesity and associated metabolic disorders in mice. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1220044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mangel L, Bíró K, Battyáni I, Göcze P, Tornóczky T, Kálmán E. A case study on the potential angiogenic effect of human chorionic gonadotropin hormone in rapid progression and spontaneous regression of metastatic renal cell carcinoma during pregnancy and after surgical abortion. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:1013. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Mullish BH, Williams HR. Clostridium difficile infection and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea. Clin Med (Lond). 2018;18:237-241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Zha L, Garrett S, Sun J. Salmonella Infection in Chronic Inflammation and Gastrointestinal Cancer. Diseases. 2019;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Alon-Maimon T, Mandelboim O, Bachrach G. Fusobacterium nucleatum and cancer. Periodontol 2000. 2022;89:166-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Das MR, Bag AK, Saha S, Ghosh A, Dey SK, Das P, Mandal C, Ray S, Chakrabarti S, Ray M, Jana SS. Molecular association of glucose-6-phosphate isomerase and pyruvate kinase M2 with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase in cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:152. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cheng WT, Kantilal HK, Davamani F. The Mechanism of Bacteroides fragilis Toxin Contributes to Colon Cancer Formation. Malays J Med Sci. 2020;27:9-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Clapp M, Aurora N, Herrera L, Bhatia M, Wilen E, Wakefield S. Gut microbiota's effect on mental health: The gut-brain axis. Clin Pract. 2017;7:987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 317] [Article Influence: 39.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ascione A, Arenaccio C, Mallano A, Flego M, Gellini M, Andreotti M, Fenwick C, Pantaleo G, Vella S, Federico M. Development of a novel human phage display-derived anti-LAG3 scFv antibody targeting CD8(+) T lymphocyte exhaustion. BMC Biotechnol. 2019;19:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 780] [Cited by in RCA: 1611] [Article Influence: 322.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chernikova MA, Flores GD, Kilroy E, Labus JS, Mayer EA, Aziz-Zadeh L. The Brain-Gut-Microbiome System: Pathways and Implications for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Nutrients. 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Mulder D, Aarts E, Arias Vasquez A, Bloemendaal M. A systematic review exploring the association between the human gut microbiota and brain connectivity in health and disease. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:5037-5061. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Murray ER, Kemp M, Nguyen TT. The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis in Alzheimer's Disease: A Review of Taxonomic Alterations and Potential Avenues for Interventions. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2022;37:595-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Kumar A, Pramanik J, Goyal N, Chauhan D, Sivamaruthi BS, Prajapati BG, Chaiyasut C. Gut Microbiota in Anxiety and Depression: Unveiling the Relationships and Management Options. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kumar A, Sivamaruthi BS, Dey S, Kumar Y, Malviya R, Prajapati BG, Chaiyasut C. Probiotics as modulators of gut-brain axis for cognitive development. Front Pharmacol. 2024;15:1348297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Mehra A, Arora G, Sahni G, Kaur M, Singh H, Singh B, Kaur S. Gut microbiota and Autism Spectrum Disorder: From pathogenesis to potential therapeutic perspectives. J Tradit Complement Med. 2023;13:135-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Tiwari P, Dwivedi R, Bansal M, Tripathi M, Dada R. Role of Gut Microbiota in Neurological Disorders and Its Therapeutic Significance. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 37. | Santamarina AB, de Freitas JA, Franco LAM, Nehmi-Filho V, Fonseca JV, Martins RC, Turri JA, da Silva BFRB, Fugi BEI, da Fonseca SS, Gusmão AF, Olivieri EHR, de Souza E, Costa S, Sabino EC, Otoch JP, Pessoa AFM. Nutraceutical blends predict enhanced health via microbiota reshaping improving cytokines and life quality: a Brazilian double-blind randomized trial. Sci Rep. 2024;14:11127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Benton D, Williams C, Brown A. Impact of consuming a milk drink containing a probiotic on mood and cognition. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61:355-361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 366] [Cited by in RCA: 395] [Article Influence: 20.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Rusch JA, Layden BT, Dugas LR. Signalling cognition: the gut microbiota and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1130689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 62.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Zhu J, Wang C, Qian Y, Cai H, Zhang S, Zhang C, Zhao W, Zhang T, Zhang B, Chen J, Liu S, Yu Y. Multimodal neuroimaging fusion biomarkers mediate the association between gut microbiota and cognition. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2022;113:110468. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Napolitano M, Fasulo E, Ungaro F, Massimino L, Sinagra E, Danese S, Mandarino FV. Gut Dysbiosis in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Narrative Review on Correlation with Disease Subtypes and Novel Therapeutic Implications. Microorganisms. 2023;11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Messaoudi M, Lalonde R, Violle N, Javelot H, Desor D, Nejdi A, Bisson JF, Rougeot C, Pichelin M, Cazaubiel M, Cazaubiel JM. Assessment of psychotropic-like properties of a probiotic formulation (Lactobacillus helveticus R0052 and Bifidobacterium longum R0175) in rats and human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2011;105:755-764. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 832] [Cited by in RCA: 934] [Article Influence: 62.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Kelsey CM, Prescott S, McCulloch JA, Trinchieri G, Valladares TL, Dreisbach C, Alhusen J, Grossmann T. Gut microbiota composition is associated with newborn functional brain connectivity and behavioral temperament. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;91:472-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Ullah H, Arbab S, Tian Y, Liu CQ, Chen Y, Qijie L, Khan MIU, Hassan IU, Li K. The gut microbiota-brain axis in neurological disorder. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1225875. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wu HJ, Wu E. The role of gut microbiota in immune homeostasis and autoimmunity. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:4-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 622] [Cited by in RCA: 902] [Article Influence: 69.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Ordoñez-Rodriguez A, Roman P, Rueda-Ruzafa L, Campos-Rios A, Cardona D. Changes in Gut Microbiota and Multiple Sclerosis: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2488] [Cited by in RCA: 3431] [Article Influence: 311.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Zhou P, Chen C, Patil S, Dong S. Unveiling the therapeutic symphony of probiotics, prebiotics, and postbiotics in gut-immune harmony. Front Nutr. 2024;11:1355542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Eslami M, Bahar A, Keikha M, Karbalaei M, Kobyliak NM, Yousefi B. Probiotics function and modulation of the immune system in allergic diseases. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr). 2020;48:771-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Attiq T, Alavi AF, Khan S, Najam F, Saleem M, Hassan I, Ali R, Khaskheli HK, Sardar S, Farooq F. Role of Gut Microbiota in Immune System Regulation: Gut Microbiota in Immune System Regulation. Pakistan J Health Sci. 2024;5:02-12. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 51. | Zhen J, Zhou Z, He M, Han HX, Lv EH, Wen PB, Liu X, Wang YT, Cai XC, Tian JQ, Zhang MY, Xiao L, Kang XX. The gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide and cardiovascular diseases. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1085041. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 45.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Wu WH, Zegarra-Ruiz DF, Diehl GE. Intestinal Microbes in Autoimmune and Inflammatory Disease. Front Immunol. 2020;11:597966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Martín R, Rios-Covian D, Huillet E, Auger S, Khazaal S, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Sokol H, Chatel JM, Langella P. Faecalibacterium: a bacterial genus with promising human health applications. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2023;47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Zhang YL, Li ZJ, Gou HZ, Song XJ, Zhang L. The gut microbiota-bile acid axis: A potential therapeutic target for liver fibrosis. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:945368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Schepici G, Silvestro S, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. The Gut Microbiota in Multiple Sclerosis: An Overview of Clinical Trials. Cell Transplant. 2019;28:1507-1527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Jangi S, Gandhi R, Cox LM, Li N, von Glehn F, Yan R, Patel B, Mazzola MA, Liu S, Glanz BL, Cook S, Tankou S, Stuart F, Melo K, Nejad P, Smith K, Topçuolu BD, Holden J, Kivisäkk P, Chitnis T, De Jager PL, Quintana FJ, Gerber GK, Bry L, Weiner HL. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in multiple sclerosis. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12015. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 703] [Cited by in RCA: 936] [Article Influence: 104.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Marrella V, Nicchiotti F, Cassani B. Microbiota and Immunity during Respiratory Infections: Lung and Gut Affair. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Romero-Figueroa MDS, Ramírez-Durán N, Montiel-Jarquín AJ, Horta-Baas G. Gut-joint axis: Gut dysbiosis can contribute to the onset of rheumatoid arthritis via multiple pathways. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1092118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 18.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zheng D, Liwinski T, Elinav E. Interaction between microbiota and immunity in health and disease. Cell Res. 2020;30:492-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 789] [Cited by in RCA: 2232] [Article Influence: 446.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 60. | Sadeghpour Heravi F. Gut Microbiota and Autoimmune Diseases: Mechanisms, Treatment, Challenges, and Future Recommendations. Curr Clin Micro Rpt. 2024;11:18-33. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 61. | Khor B, Snow M, Herrman E, Ray N, Mansukhani K, Patel KA, Said-Al-Naief N, Maier T, Machida CA. Interconnections Between the Oral and Gut Microbiomes: Reversal of Microbial Dysbiosis and the Balance Between Systemic Health and Disease. Microorganisms. 2021;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Zhou Z, Sun B, Yu D, Zhu C. Gut Microbiota: An Important Player in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:834485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Iatcu CO, Steen A, Covasa M. Gut Microbiota and Complications of Type-2 Diabetes. Nutrients. 2021;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 208] [Article Influence: 52.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Al-Ishaq RK, Samuel SM, Büsselberg D. The Influence of Gut Microbial Species on Diabetes Mellitus. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. J Lipid Res. 2013;54:2325-2340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2408] [Cited by in RCA: 3286] [Article Influence: 273.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 66. | Ma T, Shen X, Shi X, Sakandar HA, Quan K, Li Y, Jin H, Kwok L, Zhang H, Sun Z. Targeting gut microbiota and metabolism as the major probiotic mechanism - An evidence-based review. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2023;138:178-198. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 67. | Abdalqadir N, Adeli K. GLP-1 and GLP-2 Orchestrate Intestine Integrity, Gut Microbiota, and Immune System Crosstalk. Microorganisms. 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 17.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Gérard C, Vidal H. Impact of Gut Microbiota on Host Glycemic Control. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2019;10:29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 97] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Festi D, Schiumerini R, Eusebi LH, Marasco G, Taddia M, Colecchia A. Gut microbiota and metabolic syndrome. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16079-16094. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 342] [Cited by in RCA: 363] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 70. | Cheng Z, Zhang L, Yang L, Chu H. The critical role of gut microbiota in obesity. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1025706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Article Influence: 32.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Sarmiento-Andrade Y, Suárez R, Quintero B, Garrochamba K, Chapela SP. Gut microbiota and obesity: New insights. Front Nutr. 2022;9:1018212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Abdul-Ghani MA, Norton L, DeFronzo RA. Renal sodium-glucose cotransporter inhibition in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2015;309:F889-F900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 11.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Craciun CI, Neag MA, Catinean A, Mitre AO, Rusu A, Bala C, Roman G, Buzoianu AD, Muntean DM, Craciun AE. The Relationships between Gut Microbiota and Diabetes Mellitus, and Treatments for Diabetes Mellitus. Biomedicines. 2022;10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Murri M, Leiva I, Gomez-Zumaquero JM, Tinahones FJ, Cardona F, Soriguer F, Queipo-Ortuño MI. Gut microbiota in children with type 1 diabetes differs from that in healthy children: a case-control study. BMC Med. 2013;11:46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 496] [Cited by in RCA: 555] [Article Influence: 46.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Li J, Yang G, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Jiang X, Xin Y. Function of Akkermansia muciniphila in type 2 diabetes and related diseases. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1172400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Del Chierico F, Rapini N, Deodati A, Matteoli MC, Cianfarani S, Putignani L. Pathophysiology of Type 1 Diabetes and Gut Microbiota Role. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Zhang L, Chu J, Hao W, Zhang J, Li H, Yang C, Yang J, Chen X, Wang H. Gut Microbiota and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: Association, Mechanism, and Translational Applications. Mediators Inflamm. 2021;2021:5110276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 20.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Baars DP, Fondevila MF, Meijnikman AS, Nieuwdorp M. The central role of the gut microbiota in the pathophysiology and management of type 2 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2024;32:1280-1300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Cunningham AL, Stephens JW, Harris DA. Gut microbiota influence in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). Gut Pathog. 2021;13:50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 34.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Bielka W, Przezak A, Pawlik A. The Role of the Gut Microbiota in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Crudele L, Gadaleta RM, Cariello M, Moschetta A. Gut microbiota in the pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches of diabetes. EBioMedicine. 2023;97:104821. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 82. | Gilbert MP, Pratley RE. GLP-1 Analogs and DPP-4 Inhibitors in Type 2 Diabetes Therapy: Review of Head-to-Head Clinical Trials. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Clemente-Suárez VJ, Redondo-Flórez L, Rubio-Zarapuz A, Martín-Rodríguez A, Tornero-Aguilera JF. Microbiota Implications in Endocrine-Related Diseases: From Development to Novel Therapeutic Approaches. Biomedicines. 2024;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Liu Y, Lau HC, Yu J. Microbial metabolites in colorectal tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. Gut Microbes. 2023;15:2203968. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Li S, Liu J, Zheng X, Ren L, Yang Y, Li W, Fu W, Wang J, Du G. Tumorigenic bacteria in colorectal cancer: mechanisms and treatments. Cancer Biol Med. 2021;19:147-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Aghamajidi A, Maleki Vareki S. The Effect of the Gut Microbiota on Systemic and Anti-Tumor Immunity and Response to Systemic Therapy against Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Kunika, Frey N, Rangrez AY. Exploring the Involvement of Gut Microbiota in Cancer Therapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Laborda-Illanes A, Sanchez-Alcoholado L, Dominguez-Recio ME, Jimenez-Rodriguez B, Lavado R, Comino-Méndez I, Alba E, Queipo-Ortuño MI. Breast and Gut Microbiota Action Mechanisms in Breast Cancer Pathogenesis and Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 23.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Filippou C, Themistocleous SC, Marangos G, Panayiotou Y, Fyrilla M, Kousparou CA, Pana ZD, Tsioutis C, Johnson EO, Yiallouris A. Microbial Therapy and Breast Cancer Management: Exploring Mechanisms, Clinical Efficacy, and Integration within the One Health Approach. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 90. | Tortora SC, Bodiwala VM, Quinn A, Martello LA, Vignesh S. Microbiome and colorectal carcinogenesis: Linked mechanisms and racial differences. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2022;14:375-395. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 91. | Kalasabail S, Engelman J, Zhang LY, El-Omar E, Yim HCH. A Perspective on the Role of Microbiome for Colorectal Cancer Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Baba Y, Iwatsuki M, Yoshida N, Watanabe M, Baba H. Review of the gut microbiome and esophageal cancer: Pathogenesis and potential clinical implications. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2017;1:99-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Moreira C, Figueiredo C, Ferreira RM. The Role of the Microbiota in Esophageal Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Díaz P, Valenzuela Valderrama M, Bravo J, Quest AFG. Helicobacter pylori and Gastric Cancer: Adaptive Cellular Mechanisms Involved in Disease Progression. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 22.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Wroblewski LE, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori and gastric cancer: factors that modulate disease risk. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:713-739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 817] [Cited by in RCA: 1014] [Article Influence: 67.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |