Published online Jan 28, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i4.98752

Revised: October 25, 2024

Accepted: December 5, 2024

Published online: January 28, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 16.2 Hours

Strongyloides stercoralis (S. stercoralis), is a prevalent parasitic worm that infects humans. It is found all over the world, particularly in tropical and subtropical areas. Strongyloidiasis is caused mostly by the parasitic nematode S. stercoralis. Filariform larvae typically infest humans by coming into contact with dirt, such as by walking barefoot or through exposure to human waste or sewage.

A 35-year-old male presented to our department with a 10-year history of abdominal pain and diarrhea, which had recently recurred for the past 3 months. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed acute cholecystitis accompanied by a gallbladder stone. Additionally, a 5 mm stone was found obstructing the lower portion of the common bile duct, resulting in dilatation of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts to 8 mm, in contrast to a previous CT scan. Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a prominent echogenicity in the lower portion of the common bile duct. Consequently, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography was conducted via endoscopic sphincterotomy and balloon dilatation. The microscope revealed the presence of viable S. stercoralis rhabditiform larvae in the biliary fluid. We documented an uncommon instance of S. stercoralis infection in the biliary fluid of a patient suffering from gallstones and cholangitis.

The film we created provides a visual representation of the movement of the living S. stercoralis in biliary fluid.

Core Tip: We documented an uncommon occurrence of Strongyloides stercoralis (S. stercoralis) infection in the biliary fluid of a patient with gallstones and cholangitis. The film we recorded provides a visual representation of the movement of a living S. stercoralis in biliary fluid, a phenomenon that has not been previously documented. It is hypothesized that the presence of a living S. stercoralis could affect the process of bile extraction, leading to an increased likelihood of gallstone formation.

- Citation: Jiang XH, Deng Q, Wu ZK, Li JZ. Alive Strongyloides stercoralis in biliary fluid in patient: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(4): 98752

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i4/98752.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i4.98752

Strongyloides stercoralis (S. stercoralis) is a prevalent nematode parasite that infects humans and is found globally, particularly in tropical and subtropical areas[1]. An estimated global population of approximately 600 million people may be affected by S. stercoralis infection[2]. Strongyloidiasis is caused mostly by the parasitic nematode S. stercoralis. Filariform larvae typically invade humans via contact with soil, such as by walking barefoot or through exposure to human waste or sewage[3]. The migration from the dermal entrance to the pulmonary and gastrointestinal systems might result in acute or chronic manifestations. Patients may experience irritation or itching, as well as recurring hives at the location where the larva entered the body[4]. Transpulmonary larval migration can cause temporary bronchitis, which is characterized by symptoms such as a dry cough, wheezing, and difficulty breathing[5]. Acute gastrointestinal strongyloidiasis can result in symptoms such as epigastric discomfort, abdominal distension, stomach pain, constipation, and diarrhea. Approximately half of individuals with persistent infection may exhibit no symptoms or experience only minor symptoms. Gastrointestinal symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, changes in bowel movements, and diarrhea are frequently observed in symptomatic patients[4,6].

Some people may experience recurring gastrointestinal symptoms. In endoscopy, an infection with S. stercoralis in the duodenum and/or colon can cause superficial ulceration, leakage, and redness of the mucosa. These symptoms can resemble inflammatory bowel disease[7]. Typically, the biliary system does not play a role in the life cycle of S. stercoralis. Several cases in which S. stercoralis was detected in the biliary fluid have been reported, leading to cholecystitis, obs

Chronic abdominal pain and diarrhea persisting for 10 years, with recent recurrence over the past 3 months.

The patient had no prior history of visiting an epidemic area. Colonoscopy revealed the presence of scattered erosions and superficial ulcers on the mucosa of the colon. As a result, the individual was diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease and S. stercoralis infection a decade earlier. The patient received treatment with albendazole and prednisone. He experienced notable improvement in his symptoms. He took prednisone sporadically. Five years ago, the individual experienced intensified abdominal pain and diarrhea, along with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and the presence of mucus and pus in his stool. During that period, a laboratory analysis revealed an increased eosinophil count of 0.99 ×

The patient had no special past illnesses.

The patient had no special family history. The patient had no prior history of visiting epidemic areas. The patient had no prior history of eating raw fish or meat.

The patient had experienced abdominal pain in the area around the belly button for the past 10 years. During hospitalization, the patient experienced acute discomfort in the upper right abdomen accompanied by vomiting and fever. Murphy’s sign was positive.

The human immunodeficiency virus antibody test was negative. The levels of cytomegalovirus-DNA and Epstein-Barr virus-DNA were within the normal ranges. The values of aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ-glutamyltransferase, total bilirubin (TBIL), albumin, and amylase were within the normal ranges. Stool examination revealed the presence of viable rhabditiform larvae of S. stercoralis when observed under a microscope.

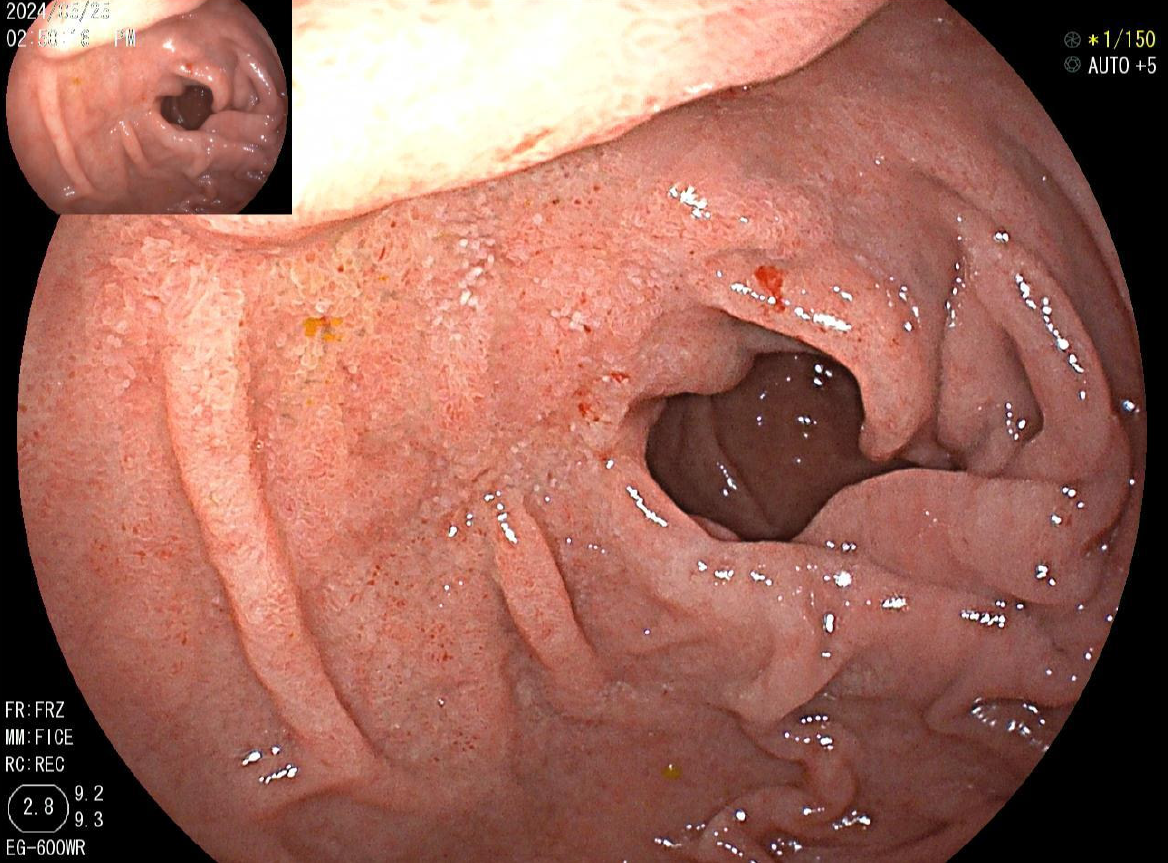

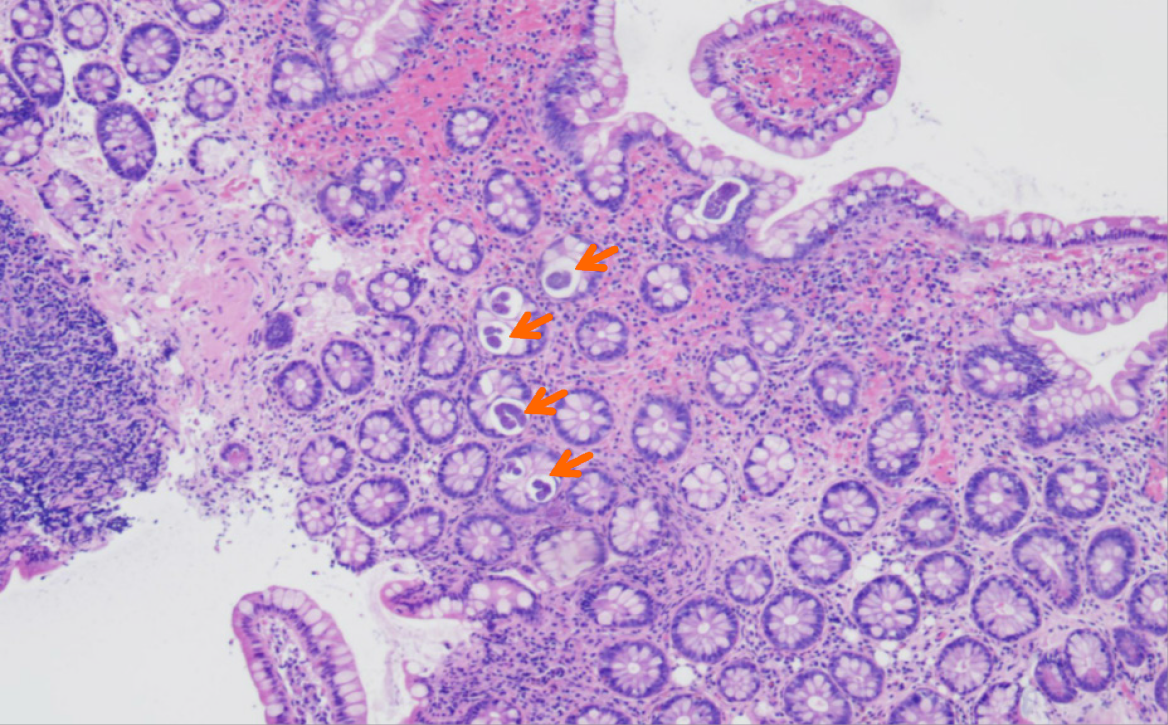

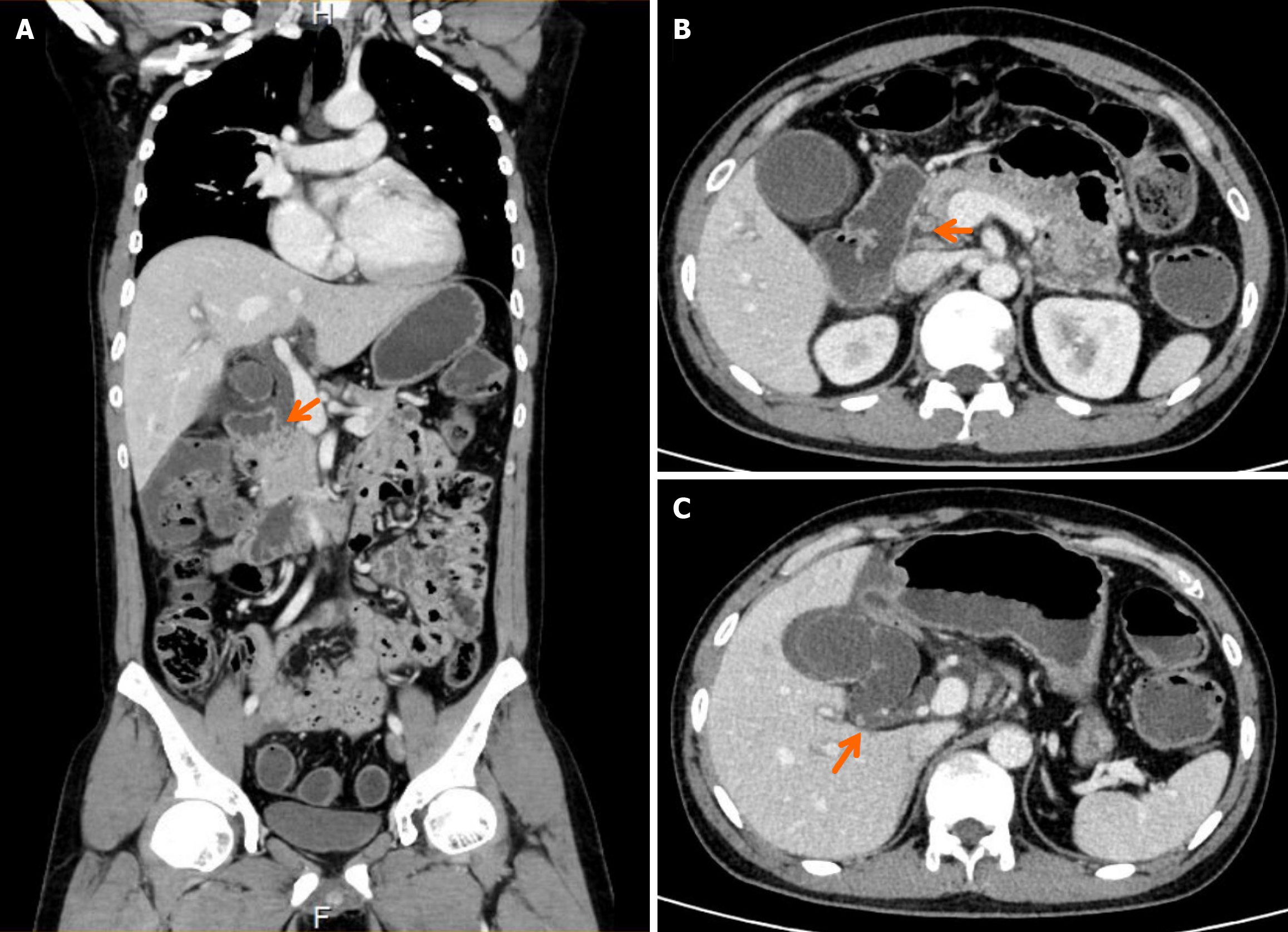

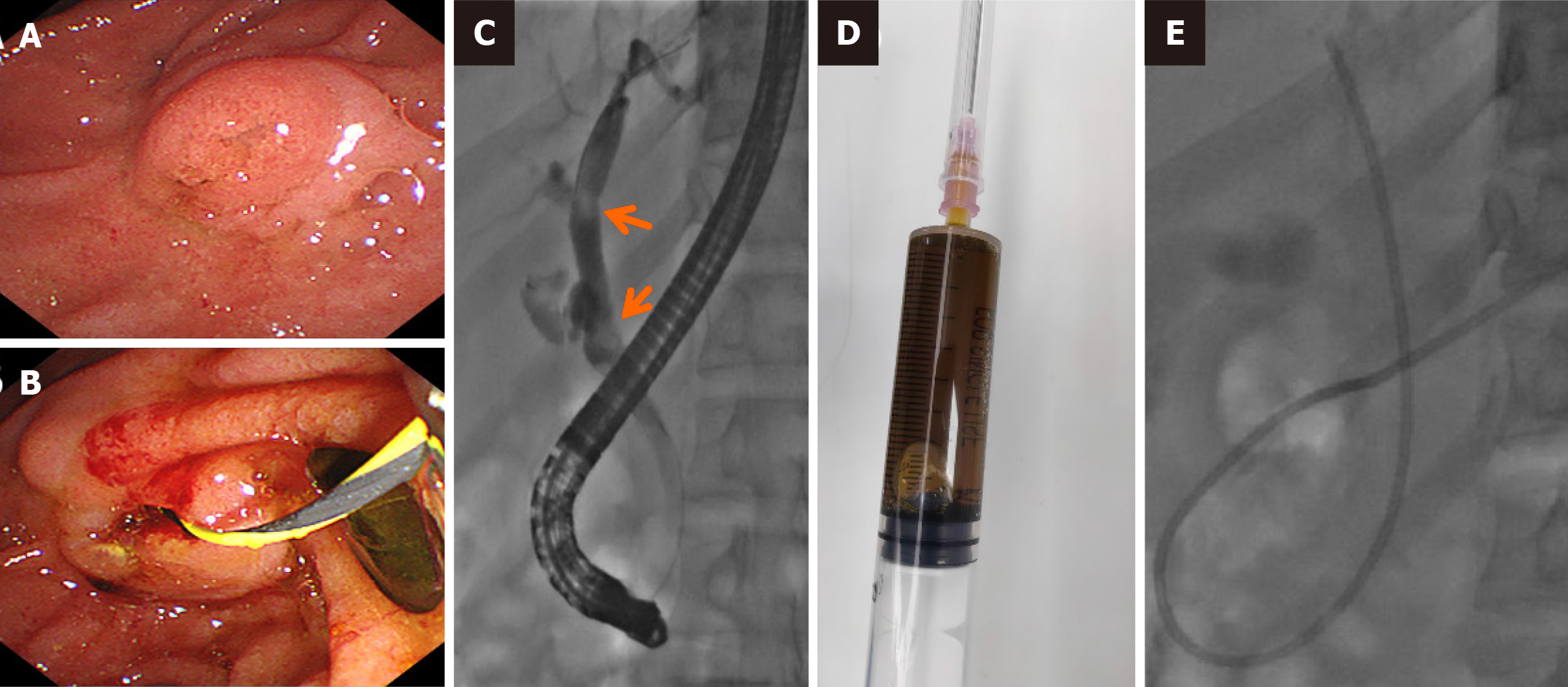

Endoscopy revealed diffuse erosions in the duodenum and inflammation with a rough surface in the colon and terminal ileum (Figure 1). Biopsy pathology revealed the presence of infiltrating neutrophil cells in both the glandular epithelium and stroma. Figure 2 shows the presence of eggs and immature forms of S. stercoralis in the glandular cavity, which is shown by their strong affinity for basophilic staining. He had palliative care and experienced amelioration of the symptoms. During hospitalized, he experienced acute discomfort in the upper right abdomen accompanied by vomiting and fever. Murphy’s sign was positive. Computed tomography (CT) scan revealed acute cholecystitis with a gallbladder stone and a 5 mm stone obstructing the lower portion of the common bile duct. Compared with a previous CT scan, this obstruction caused dilation of both the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts to 8 mm (refer to Figure 3). Endoscopic ultrasonography revealed a prominent echogenicity in the lower portion of the common bile duct. Consequently, ERCP was performed, involving the use of endoscopic sphincterotomy and balloon dilation. Two openings were detected in the duodenal papilla, showing the distinct connection of the pancreatic duct and biliary duct to the intestinal wall, without a shared channel (see Figure 4). Throughout the process, biliary fluid was gathered for laboratory analysis and culture. Two dark brown stones measuring 6 mm-7 mm in diameter were removed from the common bile duct (Figure 4). Endoscopic nasobiliary drainage was carried effectively. The biliary fluid was examined under the microscope, where alive S. stercoralis rhabditiform larvae were discovered (Figure 5 and Video 1).

The final diagnosis included: (1) S. stercoralis infection; (2) Cholangitis; and (3) Choledocholithiasis.

The patient received a daily dose of 200 μg/kg, considering his weight of 77 kg. Consequently, a two-day course of ivermectin was prescribed at a rate of 15 mg per day.

At the one-month follow-up, no S. stercoralis was detected on fecal examination.

Infection of the biliary system by S. stercoralis is infrequent because accessing the bile duct is difficult. Direct evidence of S. stercoralis infection in biliary fluid is rarely recorded, unless the bile juice is extracted via ERCP or PTCD. We searched for case reports on S. stercoralis infection in biliary fluid that were published in PubMed. Only three case reports were found, as indicated in Table 1 and referenced in[8,11,12]. Two individuals experienced cholecystitis accompanied by biliary blockage, while another patient received a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. All of the patients underwent ERCP; however, biliary fluid was successfully removed via ERCP in only one patient. Rhabditiform larvae were detected in the bile samples obtained from the two subjects who underwent PTCD, and in one case, S. stercoralis infection was confirmed by examining the biliary fluid taken during ERCP. Our case represents the first documentation of the presence of live rhabditiform larvae in biliary fluid obtained from ERCP via video technology. The current case experienced symptoms of acute pain in the upper right abdomen, accompanied by fever and abnormal liver function characterized by increased levels of AST, ALT, and TBIL. These symptoms were the result of gallstones obstructing the common bile duct, leading to cholangitis. The biliary fluid test revealed the presence of live S. stercoralis rhabditiform larvae, indicating that the larvae had migrated from the gut to the biliary tract through the duodenal papilla. Importantly, the biliary system is not normally involved in the life cycle of S. stercoralis. The living S. stercoralis exhibited erratic movement and “swimming” within the bile juice present in the biliary duct and gallbladder. This caused a disruption in the normal flow of biliary fluid, leading to the formation of biliary sludge. The presence of living S. stercoralis could affect the process of bile extraction, hence facilitating the development of gallstones. In this particular example, no occurrence of pancreatitis was noted before or after ERCP due to the separation of the biliary system and pancreatic duct. Ikeuchi et al[9] reported a case in which S. stercoralis infection led to obstructive jaundice and pancreatitis that did not respond to treatment. S. stercoralis was not detected in the bile juice but was detected in the biopsy of the duodenal papilla[9]. The author hypothesized that infection with S. stercoralis could cause papillitis, which in turn could lead to the development of acute cholangitis and recurrent episodes of acute pancreatitis. Additionally, other occurrences of S. stercoralis infection impacting the papilla, bile duct, and pancreas have been reported, resulting in symptoms such as jaundice, cholecystitis, or pancreatitis. However, the evidence was not convincing because there were no direct observations of biliary drainage. S. stercoralis infection can be detected in certain cases through the examination of a duodenal papilla biopsy or stool sample[10,13-15]. However, in our study, both the duodenum and biliary fluid contained S. stercoralis larvae, which served as conclusive evidence that S. stercoralis infection impacted the biliary tract, leading to cholangitis. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain the gallstone for additional studies to confirm the presence of S. stercoralis larvae in the stones.

| Ref. | Year | Diagnosis | Biliary sample | Form of S. stercoralis | Stool | Gallstone | Dilation of bile duct | Dilation of pancreatic duct | ERCP |

| Delarocque et al[12] | 1994 | Biliary obstruction | PTCD | Rhabditiform larvae | Yes | No | Yes | No | Unsuccessful |

| Perez-Jorge and Burdette[11] | 2008 | Acute pancreatitis | ERCP | S. stercoralis | Not mention | No | No | No | Yes |

| Filkins et al[8] | 2017 | Cholecystitis and extensive portal vein thrombosis | PTCD | Rhabditiform larvae | Not Mention | No | Yes | No | Normal |

| Our case | 2024 | Gallstones and cholangitis | ERCP | Rhabditiform larvae | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes |

We documented an uncommon occurrence of S. stercoralis infection in the biliary fluid of a patient suffering from gallstones and cholangitis. The film we created provides a visual representation of the movement of living S. stercoralis in biliary fluid, a phenomenon that had not been previously documented. Acquiring additional information on the life habits of S. stercoralis may prove beneficial. Additional evidence concerning the life cycle and pathogenesis of S. stercoralis is needed.

| 1. | Schär F, Trostdorf U, Giardina F, Khieu V, Muth S, Marti H, Vounatsou P, Odermatt P. Strongyloides stercoralis: Global Distribution and Risk Factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 483] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Buonfrate D, Bisanzio D, Giorli G, Odermatt P, Fürst T, Greenaway C, French M, Reithinger R, Gobbi F, Montresor A, Bisoffi Z. The Global Prevalence of Strongyloides stercoralis Infection. Pathogens. 2020;9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 245] [Article Influence: 49.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Widjana DP, Sutisna P. Prevalence of soil-transmitted helminth infections in the rural population of Bali, Indonesia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2000;31:454-459. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Buonfrate D, Fittipaldo A, Vlieghe E, Bottieau E. Clinical and laboratory features of Strongyloides stercoralis infection at diagnosis and after treatment: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:1621-1628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gordon CA, Utzinger J, Muhi S, Becker SL, Keiser J, Khieu V, Gray DJ. Strongyloidiasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2024;10:6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mukaigawara M, Narita M, Shiiki S, Takayama Y, Takakura S, Kishaba T. Clinical Characteristics of Disseminated Strongyloidiasis, Japan, 1975-2017. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:401-408. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gomez-Hinojosa P, García-Encinas C, Carlin-Ronquillo A, Chancafe-Morgan R, Espinoza-Ríos J. Strongyloides infection mimicking inflammatory bowel disease. Revista de Gastroenterología de México (English Edition). 2020;85:366-368. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Filkins LM, Gaston DC, Mathison B, Smith T, Couturier MR, Murphy RD, Ciarkowski C, Hanson KE, Cariello PF. Biliary Strongyloides stercoralis With Cholecystitis and Extensive Portal Vein Thrombosis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:ofx217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ikeuchi N, Itoi T, Tonozuka R, Mukai S, Koyama Y, Tsuchiya T, Matsumoto T, Mizuno Y, Nakamura I, Hino A, Moriyasu F. Strongyloides stercoralis Infection Causing Obstructive Jaundice and Refractory Pancreatitis: A Lesson Learned from a Case Study. Intern Med. 2016;55:2081-2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Hirata T, Kishimoto K, Kinjo N, Hokama A, Kinjo F, Fujita J. Association between Strongyloides stercoralis infection and biliary tract cancer. Parasitol Res. 2007;101:1345-1348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Perez-Jorge EV, Burdette SD. Association between acute pancreatitis and Strongyloides stercoralis. South Med J. 2008;101:771-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Delarocque Astagneau E, Hadengue A, Degott C, Vilgrain V, Erlinger S, Benhamou JP. Biliary obstruction resulting from Strongyloides stercoralis infection. Report of a case. Gut. 1994;35:705-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Pijls NH, Yap SH, Rosenbusch G, Prenen H. Pancreatic mass due to Strongyloides stercoralis infection: an unusual manifestation. Pancreas. 1986;1:90-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gupta L, Gaur K, Sakhuja P, Sharma BC, Saran RK, Batra VV. Duodenal strongyloidiasis - Our 15-year histopathological experience at a tertiary gastrointestinal centre. Trop Doct. 2021;51:219-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jones N, Cocchiarella A, Faris K, Heard SO. Pancreatitis associated with Strongyloides stercoralis infection in a patient chronically treated with corticosteroids. J Intensive Care Med. 2010;25:172-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |