Published online Mar 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i11.104033

Revised: February 3, 2025

Accepted: February 18, 2025

Published online: March 21, 2025

Processing time: 95 Days and 19.5 Hours

In this editorial, we critically evaluate the recent article by Niu et al, which ex

Core Tip: The identification of reliable biomarkers for early stratification of disease severity is essential in the management of acute pancreatitis (AP). Phospholipase D2 (PLD2), a pivotal regulator of neutrophil migration and inflammatory responses, has emerged as a promising candidate biomarker that may transform AP management by integrating molecular diagnostics with precision medicine. However, several challenges persist, including large-scale validation studies, functional investigations to establish causation, and standardization of measurement protocols. Consequently, it is imperative to critically examine and rigorously validate the role of PLD2 to ensure its effectiveness in improving patient outcomes.

- Citation: Wang ZH, Lv JH, Teng Y, Michael N, Zhao YF, Xia M, Wang B. Phospholipase D2: A biomarker for stratifying disease severity in acute pancreatitis? World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(11): 104033

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i11/104033.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i11.104033

Acute pancreatitis (AP) continues to pose a significant challenge in gastroenterology, with global incidence rates on the rise and mortality reaching up to 30% in severe cases[1,2]. The unpredictable trajectory of AP, ranging from mild self-limiting inflammation to severe multi-organ failure, underscores an urgent need for reliable biomarkers that can accurately stratify disease severity and facilitate early intervention. Although current clinical tools such as scoring systems like the Ranson Score and the Bedside Index for Severity in Acute Pancreatitis are useful, they often lack the precision and timeliness required for accurate risk prediction[3,4]. In the initial section of this editorial, we provide an overview of biomarkers that exhibit specific utility (Table 1), although their specificity in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying AP pathogenesis remains limited[5,6].

| Marker | Sensitivity[7,24] | Specificity[7,24] | Validation stage[7,24] | Advantages | Disadvantages |

| IL | 93.1%-100% | 89.7%-96.8% | Clinical application | IL-6 accurately predicts severity in AP[8,9] | Constrained by cost and assay complexity[10] |

| CRP | 80%-86% | 61%-84% | Widely used | Predicting AP severity with low cost and easy availability[13,14] | Lack of specificity[5]; Delayed detection[14] |

| TNF-α | Inconsistent | Inconsistent | Research stage | Correlating with the severity of AP[15] | Unclear predictive value in AP[16,17] |

| TF | Not specified | Not specified | Research stage | High serum TF in early stages of AP[19] | Superior to CRP but inferior to IL-6[18] |

| PCT | 73%-100% | 86%-87% | Research stage | PCT predicts AP severity at an early stage[6] | The procalcitonin assay is uneconomical |

| Amylase | 55%-84% | 95% | Clinical application | An early diagnostic marker for AP[10] | Limited in determining AP severity [20] |

| Lipase | 80% | 60% | Widely used | High sensitivity and specificity[10,21] | Limited in determining severity and etiology[22] |

| Trypsinogen | Not specified | Not specified | Research stage | Trypsinogen can be rapidly detected in AP[23] | Low sensitivity and limited usability[21] |

Interleukins (ILs), such as IL-1, IL-6, and IL-8, play a crucial role in the development and progression of inflammatory processes[7]. Numerous studies have demonstrated a significant correlation between specific members of the IL family and AP, particularly IL-6, which has been closely associated with the severity of AP[8,9]. However, its clinical application is constrained by its complexity and cost[10,11].

The production of C-reactive protein (CRP) is stimulated by cytokines such as IL-6, leading to a rapid elevation of CRP levels in the bloodstream within hours following inflammation and infection[12]. CRP is extensively employed for the diagnosis, prognostication, treatment monitoring, and mortality prediction, especially in inflammatory conditions[13]. Its cost-effectiveness and ease of accessibility further enhance its widespread use. Nevertheless, limitations persist, including low specificity and delayed detection[5,14]. Additionally, several studies have reported an association between the severity of AP and levels of tumor necrosis factor-α; however, these findings have been inconsistent and inconclusive[15-17].

Tissue factor (TF) serves as a more potent biomarker for assessing the severity of AP compared to CRP, but it is deemed less reliable than IL-6. Elevated serum levels of TF in the early stages of AP may indicate its involvement in disease progression and provide an opportunity for therapeutic intervention[18,19].

Procalcitonin (PCT) exhibits remarkably high sensitivity to pancreatic infections, making it efficacious for early-stage severity prediction. However, its clinical adoption remains limited due to the relatively high associated costs[6,14].

The concentration of blood amylase can rapidly increase and be detected following the onset of AP[10], but its utility in determining disease severity is limited by the lack of correlation between post-peak concentration changes and disease remission[20]. Lipase demonstrates excellent specificity and sensitivity as a biomarker for AP, yet its capacity to assess disease severity remains restricted[10,21,22]. Trypsinogen, while detectable early in AP patients, is not commonly used in clinical practice due to its limited sensitivity and availability[21,23].

Furthermore, leveraging the existing research data, we have systematically analyzed and summarized the sensitivity, specificity, and current clinical application stages of biomarkers for AP (Table 1)[7,24]. From a broader perspective, many of these biomarkers exhibit insufficient specificity or their regulatory mechanisms remain unvalidated by research. Consequently, the identification of novel biomarkers is imperative for enhancing diagnosis and treatment strategies. The future of AP management lies in precision diagnostics that not only reflect the inflammatory burden but also provide actionable insights into the underlying disease mechanism. Recently, Phospholipase D2 (PLD2), a key regulator of cellular signaling and immune responses, has emerged as a potential candidate biomarker[25]. Niu et al's study provides compelling evidence that reduced PLD2 expression correlates with increased severity of AP[26]. While this finding shows promise, it raises crucial questions: Does PLD2 represent a genuine mechanistic link in AP progression? Can its clinical utility extend beyond correlation to offer predictive or therapeutic advantages?

This editorial critically evaluates the potential of PLD2 as a diagnostic biomarker in AP research and highlights the necessary steps for validating its utility. Additionally, we envision a future where molecular biomarkers like PLD2 can revolutionize the approach toward AP by transitioning from reactive care to predictive and personalized strategies.

The biomarkers traditionally employed for assessing the severity of AP have primarily focused on systemic inflammation markers such as CRP and PCT[6,14], or indicators of organ dysfunction. While these markers are valuable, they predominantly reflect the downstream effects of inflammation rather than its underlying molecular drivers.

The identification of PLD2 represents a significant advancement in this paradigm as it plays a crucial role in regulating neutrophil migration, which is a critical event in the initiation and propagation of inflammation in AP[27]. Research has implicated neutrophil migration in AP, with studies indicating that excessive infiltration of neutrophils exacerbates tissue damage, amplifies cytokine storms, and accelerates systemic inflammatory response syndrome[28]. PLD2 appears to modulate this process by limiting neutrophil chemotaxis, as evidenced by both the current study of Niu et al[26] and earlier preclinical research[27]. Importantly, the inverse relationship between PLD2 levels and AP severity underscores its potential as a relevant biomarker. However, biomarkers must meet stringent criteria including sensitivity, specificity, reproducibility, and ease of measurement[29]. Therefore, the utility of PLD2 requires rigorous evaluation to address several challenges as outlined below.

The observed correlation between reduced PLD2 levels and the severity of AP suggests a potential role of PLD2 in disease progression. However, it remains unclear whether PLD2 actively regulates this process or if its effects are merely reflective of severe inflammation as a bystander[30]. To elucidate this relationship, functional studies utilizing targeted modulation of PLD2 in vivo are necessary.

The literature indicates a strong correlation between PLD2 expression levels and the severity of pancreatic inflammation in AP[30]. Wu et al[25] proposed that PLD2 may regulate AP through the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway. Additional studies suggest that cell signaling pathways, including NADPH oxidase activation and reactive oxygen species production, contributes to the pro-inflammatory response and progression of AP lesions[31]. Zhou et al[30] demonstrated that PLD2 controls apoptosis and edema in pancreatic cells via the Nrf2/NF-κB pathway, contributing to AP management. Furthermore, PLD2 has been shown to regulate cell migration and phagocytosis by Han et al[32], and Gomez-Cambronero[33], providing a basis for further investigation by Niu et al[26]. Dysregulated autophagy represents a hallmark of AP pathogenesis, and is also associated with the role of PLD2 in modulating autophagic flux[34]. Aberrant activity of PLD2 may affect the formation and accumulation of autophagosomes by modulating the expression or activity of autophagy-related genes such as autophagy-related gene 5 and autophagy-related gene 7, thereby influencing inflammation and tissue damage. Besides, PLD2 could also regulate lysosomal function by influencing the expression or stability of lysosomal membrane proteins such as lysosome-associated membrane protein 2, promoting the fusion of autophagosomes with lysosomes and accelerating the degradation of autophagosome contents, which in turn may alleviate inflammatory responses and tissue damage[26,34]. Moreover, research on alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) revealed upregulation of PLD2 expression during ALD progression along with increased expression of pro-inflammatory and pro-lipid genes[35]. A similar mechanism may occur in AP; however, this hypothesis lacks current research confirmation.

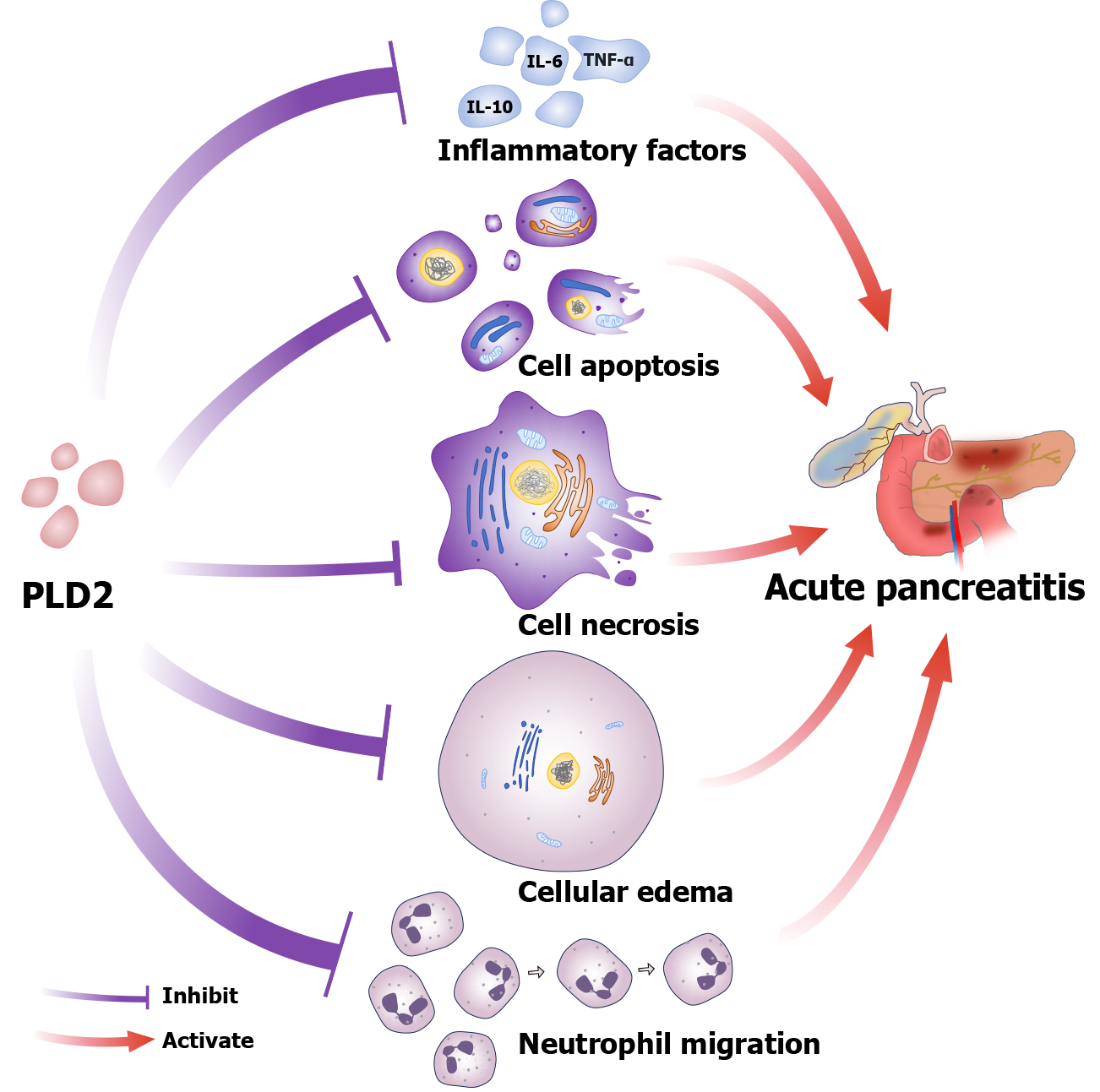

In conclusion, PLD2 primarily regulates AP by modulating the production of inflammatory factor, apoptosis and necrosis, cellular edema, and neutrophil migration (Figure 1). The findings suggest that targeting PLD2 may represent a promising therapeutic strategy for managing AP through the modulation of inflammation and reduction of cellular damage. Additionally, further in vivo studies are essential to elucidate the precise mechanisms and fully explore its therapeutic potential.

The inflammatory responses display considerable interpatient variability, influenced by genetic, environmental, and comorbid factors. This raises the question of PLD2's predictive consistency across diverse populations.

Genetic predisposition significantly determines an individual's susceptibility to inflammatory diseases, while environmental factors substantially contribute to the onset and exacerbation of these conditions[36,37]. Although PLD2 holds potential as a biomarker for AP, its predictive value may vary due to genetic variability. Further research is imperative to validate the consistency of PLD2 as a predictive biomarker in larger and more diverse patient cohorts.

The temporal relationship between PLD2 expression and onset and progression of AP remains uncertain. Biomarkers that emerge later in the disease process have limited predictive value for early intervention.

Previous sections of this article have discussed the correlation between PLD2 expression levels and AP. For instance, upregulation of PLD2 has been shown to decrease pro-inflammatory mRNA levels, suggesting that it may alleviate inflammation by negatively regulating key inflammatory mediators[30]. Niu et al's study also demonstrated that PLD2 regulates AP through its effect on neutrophil migration[26]. These findings indicate that changes in PLD2 expression are associated with the initiation and progression of AP. However, these studies do not directly address the temporal dynamics between PLD2 expression and AP. Therefore, further research is required to elucidate its potential as an early intervention biomarker.

If the correlation between PLD2 and AP progression is confirmed, PLD2 holds potential as a biomarker for early diagnosis, enabling timely intervention before severe pancreatic damage occurs. Furthermore, PLD2 may aid in assessing AP severity, thereby assisting clinicians in formulating personalized treatment strategies based on disease progression. Additionally, the expression patterns of PLD2 could offer valuable insights into patient prognosis, guiding recovery plans and long-term management.

The integration of PLD2 with advancements in molecular diagnostics, systems biology, and precision medicine is imperative for its development as a transformative biomarker[38]. The following steps delineate a strategic roadmap to realize this potential.

Integrating PLD2 with multi-omics approaches (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) can significantly enhance its predictive power as a biomarker for AP[39]. Multi-omics data provide a comprehensive un

Genetic variations in the PLD2 gene or its regulatory elements may influence its expression levels and inflammatory responses. Genome-wide association studies could identify variants linked to AP severity. Transcriptomic profiling via RNA sequencing could reveal co-expressed inflammatory genes, elucidating how PLD2 interacts with pathways such as NF-κB or Nrf2 in AP[40].

Mass spectrometry-based proteomics could quantify PLD2 protein levels and modifications across different stages of AP. Protein interaction studies could uncover PLD2-associated signaling networks, aiding in the identification of therapeutic targets[41]. Moreover, metabolic profiling could assess the impact of PLD2 on lipid metabolism and inflammatory mediators in AP. Lipidomic analysis could investigate the role of phospholipase D activity in AP progression. By integrating these datasets, researchers can develop predictive models that improve diagnostic accuracy, personalize treatment strategies, and explore PLD2-targeted therapies[42].

Establishing standardized protocols for quantifying PLD2 is critical to ensure reproducibility and enhance its clinical utility.

Future research should prioritize large-scale validation of PLD2 as a biomarker through prospective, multicenter cohort studies. Cohort recruitment should emphasize robust representation to capture the variability in disease ex

Should the modulation of PLD2 be demonstrated to directly influence AP outcomes, it could evolve from a purely diagnostic marker into a dual-purpose biomarker and therapeutic target[25,30].

The transition of PLD2 from a diagnostic biomarker to a therapeutic target is contingent upon several key principles: Elucidating the underlying mechanism, validating the therapeutic effect, and ensuring practical applicability[45]. If PLD2 can be shown to actively modulate disease severity in AP through its involvement in inflammation, neutrophil migration, and cell death, it may become a viable target for small molecules, biologics, or gene therapies aimed at improving patient outcomes. However, this transition is complex and necessitates a systematic, step-by-step approach to ensure both clinical feasibility and efficacy.

First, validating the mechanism is essential, including investigating how PLD2 regulates inflammation and tissue damage using in vivo models, humanized systems, and clinical trials. Second, establishing clinical feasibility requires early intervention; measuring PLD2 levels early can help stratify patients at risk of severe AP, enabling targeted therapy before irreversible damage occurs. Large-scale validation across diverse populations is crucial to move from theory to practice. A multicenter trial will confirm the predictive value and therapeutic potential of PLD2 in patient populations with varying genetic backgrounds and comorbidities[46].

The PLD2 biomarker provides a promising insight into the future direction of AP biomarker research by linking molecular mechanisms with clinical outcomes, thereby enhancing diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic potential. However, its role remains ambiguous due to unresolved questions regarding its function, variability, and timing. Future research should focus on more detailed fundamental studies, large-scale multicenter clinical validations, and standardization efforts for biomarkers, which may help resolve the current challenges faced in its clinical application in AP.

| 1. | Iannuzzi JP, King JA, Leong JH, Quan J, Windsor JW, Tanyingoh D, Coward S, Forbes N, Heitman SJ, Shaheen AA, Swain M, Buie M, Underwood FE, Kaplan GG. Global Incidence of Acute Pancreatitis Is Increasing Over Time: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterology. 2022;162:122-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 346] [Article Influence: 115.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Petrov MS, Shanbhag S, Chakraborty M, Phillips AR, Windsor JA. Organ failure and infection of pancreatic necrosis as determinants of mortality in patients with acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:813-820. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 517] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 37.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ong Y, Shelat VG. Ranson score to stratify severity in Acute Pancreatitis remains valid - Old is gold. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:865-877. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gao W, Yang HX, Ma CE. The Value of BISAP Score for Predicting Mortality and Severity in Acute Pancreatitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0130412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sproston NR, Ashworth JJ. Role of C-Reactive Protein at Sites of Inflammation and Infection. Front Immunol. 2018;9:754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 899] [Cited by in RCA: 1700] [Article Influence: 242.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Purkayastha S, Chow A, Athanasiou T, Cambaroudis A, Panesar S, Kinross J, Tekkis P, Darzi A. Does serum procalcitonin have a role in evaluating the severity of acute pancreatitis? A question revisited. World J Surg. 2006;30:1713-1721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Silva-Vaz P, Abrantes AM, Castelo-Branco M, Gouveia A, Botelho MF, Tralhão JG. Multifactorial Scores and Biomarkers of Prognosis of Acute Pancreatitis: Applications to Research and Practice. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 16.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Mititelu A, Grama A, Colceriu MC, Benţa G, Popoviciu MS, Pop TL. Role of Interleukin 6 in Acute Pancreatitis: A Possible Marker for Disease Prognosis. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Soyalp M, Yalcin M, Oter V, Ozgonul A. Investigation of procalcitonin, IL-6, oxidative stress index (OSI) plasma and tissue levels in experimental mild and severe pancreatitis in rats. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2017;118:137-141. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Matull WR, Pereira SP, O'Donohue JW. Biochemical markers of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:340-344. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 156] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang J, Niu J, Yang J. Interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and interleukin-10 in estimating the severity of acute pancreatitis: an updated meta-analysis. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61:215-220. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Lelubre C, Anselin S, Zouaoui Boudjeltia K, Biston P, Piagnerelli M. Interpretation of C-reactive protein concentrations in critically ill patients. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:124021. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mayer AD, McMahon MJ, Bowen M, Cooper EH. C reactive protein: an aid to assessment and monitoring of acute pancreatitis. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:207-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Párniczky A, Lantos T, Tóth EM, Szakács Z, Gódi S, Hágendorn R, Illés D, Koncz B, Márta K, Mikó A, Mosztbacher D, Németh BC, Pécsi D, Szabó A, Szücs Á, Varjú P, Szentesi A, Darvasi E, Erőss B, Izbéki F, Gajdán L, Halász A, Vincze Á, Szabó I, Pár G, Bajor J, Sarlós P, Czimmer J, Hamvas J, Takács T, Szepes Z, Czakó L, Varga M, Novák J, Bod B, Szepes A, Sümegi J, Papp M, Góg C, Török I, Huang W, Xia Q, Xue P, Li W, Chen W, Shirinskaya NV, Poluektov VL, Shirinskaya AV, Hegyi PJ, Bátovský M, Rodriguez-Oballe JA, Salas IM, Lopez-Diaz J, Dominguez-Munoz JE, Molero X, Pando E, Ruiz-Rebollo ML, Burgueño-Gómez B, Chang YT, Chang MC, Sud A, Moore D, Sutton R, Gougol A, Papachristou GI, Susak YM, Tiuliukin IO, Gomes AP, Oliveira MJ, Aparício DJ, Tantau M, Kurti F, Kovacheva-Slavova M, Stecher SS, Mayerle J, Poropat G, Das K, Marino MV, Capurso G, Małecka-Panas E, Zatorski H, Gasiorowska A, Fabisiak N, Ceranowicz P, Kuśnierz-Cabala B, Carvalho JR, Fernandes SR, Chang JH, Choi EK, Han J, Bertilsson S, Jumaa H, Sandblom G, Kacar S, Baltatzis M, Varabei AV, Yeshy V, Chooklin S, Kozachenko A, Veligotsky N, Hegyi P; Hungarian Pancreatic Study Group. Antibiotic therapy in acute pancreatitis: From global overuse to evidence based recommendations. Pancreatology. 2019;19:488-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ozhan G, Yanar HT, Ertekin C, Alpertunga B. Polymorphisms in tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNFalpha) gene in patients with acute pancreatitis. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010:482950. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Exley AR, Leese T, Holliday MP, Swann RA, Cohen J. Endotoxaemia and serum tumour necrosis factor as prognostic markers in severe acute pancreatitis. Gut. 1992;33:1126-1128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Domínguez-Muñoz JE, Carballo F, García MJ, Miguel de Diego J, Gea F, Yangüela J, de la Morena J. Monitoring of serum proteinase--antiproteinase balance and systemic inflammatory response in prognostic evaluation of acute pancreatitis. Results of a prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 1993;38:507-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Andersson E, Axelsson J, Eckerwall G, Ansari D, Andersson R. Tissue factor in predicted severe acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:6128-6134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ou ZB, Miao CM, Ye MX, Xing DP, He K, Li PZ, Zhu RT, Gong JP. Investigation for role of tissue factor and blood coagulation system in severe acute pancreatitis and associated liver injury. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;85:380-388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Clavien PA, Robert J, Meyer P, Borst F, Hauser H, Herrmann F, Dunand V, Rohner A. Acute pancreatitis and normoamylasemia. Not an uncommon combination. Ann Surg. 1989;210:614-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lippi G, Valentino M, Cervellin G. Laboratory diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: in search of the Holy Grail. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2012;49:18-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ismail OZ, Bhayana V. Lipase or amylase for the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis? Clin Biochem. 2017;50:1275-1280. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Rompianesi G, Hann A, Komolafe O, Pereira SP, Davidson BR, Gurusamy KS. Serum amylase and lipase and urinary trypsinogen and amylase for diagnosis of acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD012010. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Meher S, Mishra TS, Sasmal PK, Rath S, Sharma R, Rout B, Sahu MK. Role of Biomarkers in Diagnosis and Prognostic Evaluation of Acute Pancreatitis. J Biomark. 2015;2015:519534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 6.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Wu H, Chen H, Zhou R. Phospholipase D2 targeted by miR-5132-5p alleviates cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis via the Nrf2/NFκB pathway. Immun Inflamm Dis. 2023;11:e831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Niu JW, Zhang GC, Ning W, Liu HB, Yang H, Li CF. Clinical effects of phospholipase D2 in attenuating acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2025;31:97239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 27. | Lehman N, Di Fulvio M, McCray N, Campos I, Tabatabaian F, Gomez-Cambronero J. Phagocyte cell migration is mediated by phospholipases PLD1 and PLD2. Blood. 2006;108:3564-3572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Karki R, Kanneganti TD. The 'cytokine storm': molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends Immunol. 2021;42:681-705. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 252] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Chau CH, Rixe O, McLeod H, Figg WD. Validation of analytic methods for biomarkers used in drug development. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5967-5976. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 162] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhou R, Fan Y, Wu H, Zhan S, Shen J, Zhu M. The molecular mechanism of PLD2-mediated regulation of apoptosis and cell edema in pancreatic cells via the Nrf2/NF-κB pathway. Sci Rep. 2024;14:25563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Georgiou AC, Cornejo Ulloa P, Van Kessel GMH, Crielaard W, Van der Waal SV. Reactive oxygen species can be traced locally and systemically in apical periodontitis: A systematic review. Arch Oral Biol. 2021;129:105167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Han F, Chen H, Chen L, Yuan C, Shen Q, Lu G, Chen W, Gong W, Ding Y, Gu A, Tao L. Inhibition of Gasdermin D blocks the formation of NETs and protects acute pancreatitis in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023;654:26-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Gomez-Cambronero J. The exquisite regulation of PLD2 by a wealth of interacting proteins: S6K, Grb2, Sos, WASp and Rac2 (and a surprise discovery: PLD2 is a GEF). Cell Signal. 2011;23:1885-1895. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Hwang WC, Kim MK, Song JH, Choi KY, Min do S. Inhibition of phospholipase D2 induces autophagy in colorectal cancer cells. Exp Mol Med. 2014;46:e124. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Guo Y, Li J, Miao X, Wang H, Ge H, Xu H, Wang J, Wang Y. Phospholipase D2 drives cellular lipotoxicity and tissue inflammation in alcohol-associated liver disease. Life Sci. 2024;358:123166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Imahara SD, O'Keefe GE. Genetic determinants of the inflammatory response. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2004;10:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Kim ME, Lee JS. Molecular Foundations of Inflammatory Diseases: Insights into Inflammation and Inflammasomes. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2024;46:469-484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Lin Y, Qian F, Shen L, Chen F, Chen J, Shen B. Computer-aided biomarker discovery for precision medicine: data resources, models and applications. Brief Bioinform. 2019;20:952-975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sanches PHG, de Melo NC, Porcari AM, de Carvalho LM. Integrating Molecular Perspectives: Strategies for Comprehensive Multi-Omics Integrative Data Analysis and Machine Learning Applications in Transcriptomics, Proteomics, and Metabolomics. Biology (Basel). 2024;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Lessard S, Chao M, Reis K; FinnGen; Estonian Biobank Research Team, Beauvais M, Rajpal DK, Sloane J, Palta P, Klinger K, de Rinaldis E, Shameer K, Chatelain C. Leveraging large-scale multi-omics evidences to identify therapeutic targets from genome-wide association studies. BMC Genomics. 2024;25:1111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Kumar D, Bansal G, Narang A, Basak T, Abbas T, Dash D. Integrating transcriptome and proteome profiling: Strategies and applications. Proteomics. 2016;16:2533-2544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lin C, Tian Q, Guo S, Xie D, Cai Y, Wang Z, Chu H, Qiu S, Tang S, Zhang A. Metabolomics for Clinical Biomarker Discovery and Therapeutic Target Identification. Molecules. 2024;29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Johnson-Williams B, Jean D, Liu Q, Ramamoorthy A. The Importance of Diversity in Clinical Trials. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2023;113:486-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Lee DW, Cho CM. Predicting Severity of Acute Pancreatitis. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022;58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Zhou Y, Tao L, Qiu J, Xu J, Yang X, Zhang Y, Tian X, Guan X, Cen X, Zhao Y. Tumor biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis and targeted therapy. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 227] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 153.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Lawler M, Keeling P, Kholmanskikh O, Minnaard W, Moehlig-Zuttermeister H, Normanno N, Philip R, Popp C, Salgado R, Santiago-Walker AE, Trullas A, van Doorn-Khosrovani SBVW, Vart R, Vermeulen J, Vitaloni M, Verweij J. Empowering effective biomarker-driven precision oncology: A call to action. Eur J Cancer. 2024;209:114225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |