Published online Mar 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i11.100911

Revised: January 10, 2025

Accepted: February 13, 2025

Published online: March 21, 2025

Processing time: 195 Days and 8.1 Hours

To investigate the preoperative factors influencing textbook outcomes (TO) in Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) patients and evaluate the feasibility of an interpretable machine learning model for preoperative prediction of TO, we developed a machine learning model for preoperative prediction of TO and used the SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) technique to illustrate the prediction process.

To analyze the factors influencing textbook outcomes before surgery and to establish interpretable machine learning models for preoperative prediction.

A total of 376 patients diagnosed with ICC were retrospectively collected from four major medical institutions in China, covering the period from 2011 to 2017. Logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify preoperative variables associated with achieving TO. Based on these variables, an EXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) machine learning prediction model was constructed using the XGBoost package. The SHAP (package: Shapviz) algorithm was employed to visualize each variable's contribution to the model's predictions. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed to compare the prognostic differences between the TO-achieving and non-TO-achieving groups.

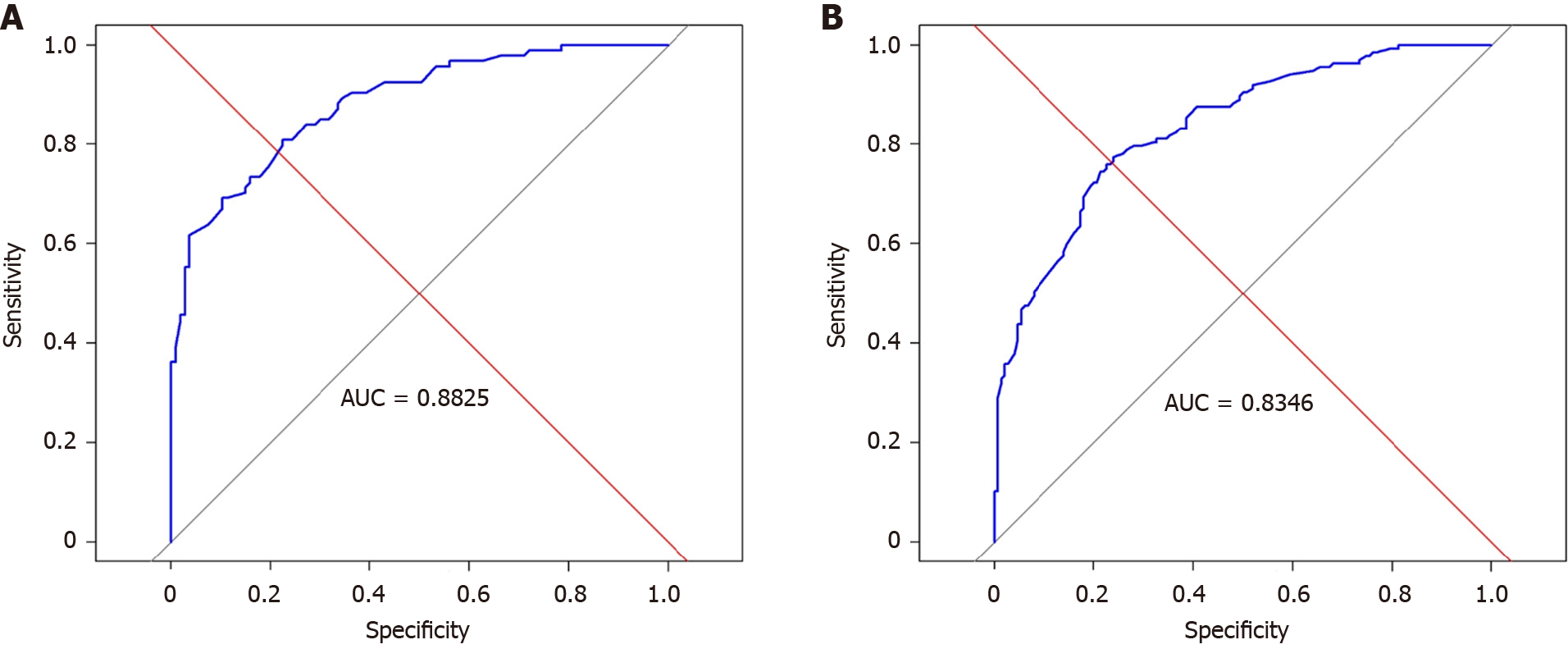

Among 376 patients, 287 were included in the training group and 89 in the validation group. Logistic regression identified the following preoperative variables influencing TO: Child-Pugh classification, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score, hepatitis B, and tumor size. The XGBoost prediction model demonstrated high accuracy in internal validation (AUC = 0.8825) and external validation (AUC = 0.8346). Survival analysis revealed that the disease-free survival rates for patients achieving TO at 1, 2, and 3 years were 64.2%, 56.8%, and 43.4%, respectively.

Child-Pugh classification, ECOG score, hepatitis B, and tumor size are preoperative predictors of TO. In both the training group and the validation group, the machine learning model had certain effectiveness in predicting TO before surgery. The SHAP algorithm provided intuitive visualization of the machine learning prediction process, enhancing its interpretability.

Core Tip: This study developed a machine learning model to preoperatively predict the Textbook outcome (TO), a measure of surgical quality and short-term prognosis, and utilized the SHapley Additive exPlanations technique to enhance model transparency. Based on the analysis of 376 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma patients from four Chinese medical institutions, logistic regression identified key preoperative factors, including Child-Pugh classification, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group score, hepatitis B status, and tumor size. The EXtreme Gradient Boosting algorithm was used to construct the prediction model, while SHAP visualized its decision-making process. The model effectively stratified recurrence-free survival, demonstrating its utility in preoperative TO prediction.

- Citation: Huang TF, Luo C, Guo LB, Liu HZ, Li JT, Lin QZ, Fan RL, Zhou WP, Li JD, Lin KC, Tang SC, Zeng YY. Preoperative prediction of textbook outcome in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by interpretable machine learning: A multicenter cohort study. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(11): 100911

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i11/100911.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i11.100911

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), the second most prevalent primary liver tumor[1], is characterized by high malignancy and rapid progression[2,3], with a globally increasing incidence[4,5]. Although surgical resection remains the primary treatment for this condition[6], over 50% of patients experience relapse within 2 years post-surgery[7,8]. Recurrence serves as a significant risk factor for poor prognosis among ICC patients[9,10].

Good postoperative conditions are one of the prerequisites for long-term survival. Thus, alongside evaluating long-term survival, assessing short-term postoperative prognosis is equally critical[11,12]. Currently, single indicators such as postoperative complications and length of hospital stay are commonly used in clinical practice to evaluate short-term postoperative prognosis[13,14]. However, these isolated metrics fail to comprehensively reflect the quality of surgery and the overall diagnosis and treatment process[15]. As a composite index for short-term postoperative prognosis, the textbook outcome (TO) provides a more accurate and comprehensive evaluation of surgical quality and overall diagnosis and treatment[16]. TO encompasses several criteria, including negative surgical margins, absence of perioperative blood transfusions, absence of postoperative complications, a short hospital stay, no deaths within 30 days of surgery, and no readmissions within 30 days of discharge[17]. Previous studies have shown that achieving TO not only facilitates better psychological and physical recovery but also improves patients' quality of life, prolongs their long-term prognosis, and may enhance disease-free survival (DFS)[18,19]. Therefore, assessing whether a patient can achieve TO serves as an important preoperative evaluation. It not only alerts medical staff to improve preoperative preparation but also lays the foundation for analyzing patient prognosis[20].

In recent years, numerous preoperative predictive models have been developed to predict the prognosis of ICC patients. For example, Zhu et al[21] constructed a nomogram model based on the immune-inflammatory-nutritional score to predict the survival and recurrence, achieving a certain level of accuracy. Xin et al[22] utilized microbiome analysis to assess risks and predict prognosis in ICC patients. Other studies have employed radiomic differences between cancerous and peritumoral tissues to predict ICC prognosis[23]. While perioperative conditions significantly influence patients' quality of life and long-term outcomes, few studies have used preoperative indicators to predict perioperative outcomes and, subsequently, patient prognosis.

In summary, determining whether patients can achieve TO before surgery holds great clinical significance. Therefore, this study applies machine learning algorithms to predict TO, enabling accurate preoperative assessment of short-term postoperative prognosis. Additionally, the incorporation of the Shapley Additive Explanation (SHAP) algorithm enhances the interpretability of the model, offering better insights into the prediction process for clinical application.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Mengchao Hepatobiliary Hospital of Fujian Medical University, and exempts the requirement of written informed consent. All procedures were performed in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki. The database was retrospectively derived from patients with pathologically confirmed ICC who underwent hepatic resection at the following institutions: Mengchao Hepatobiliary Hospital of Fujian Medical University (39 cases), Eastern Hepatobiliary Surgery Hospital of Naval Medical University (287 cases), The Second Affiliated Hospital of Zhejiang University School of Medicine (26 cases), and the Affiliated Hospital of North Sichuan Medical College (24 cases).

Inclusion criteria: (1) Patients who underwent hepatectomy; (2) Pathological confirmation of ICC; (3) No concurrent malignant tumors; and (4) Complete clinicopathologic data and follow-up information.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Receipt of other anti-tumor treatments prior to surgery; (2) Patients who underwent palliative surgery or had incomplete macroscopic tumor resection; and (3) Missing clinicopathologic data or loss to follow-up after discharge.

The evaluation criteria are as follows.

DFS: Defined as the time from surgery to death or recurrence from any cause.

Maximum tumor diameter: Defined as the preoperative tumor diameter.

Tumor burden: A solitary tumor is defined as a single lesion in the liver, whereas two or more lesions are classified as multiple tumors.

Included variables: The variables analyzed include gender, age, hepatitis B infection, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score (0, 1), Child-Pugh classification, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, alpha-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, total bilirubin, direct bilirubin, perioperative blood transfusion, surgical margins (positive or negative), complications, perioperative death or readmission within 30 days after discharge, and prolonged hospitalization.

Definition and description of variables: (1) ECOG Performance Status Scale: 0: Fully active, able to carry out all pre-disease activities without any restrictions, 1: Capable of ambulatory and light physical activity, including light housework or office work, but unable to perform moderate to heavy physical activities; (2) Child-Pugh classification: Used to assess liver function for all patients; and (3) Perioperative blood transfusion: Refers to the administration of blood products (e.g., red blood cells, platelets, plasma) during the perioperative period.

Achieving TO: Defined as meeting all of the following criteria: Negative surgical margins, no perioperative blood transfusion, no complications, no prolonged hospitalization (hospitalization duration ≤ the median length of stay for the cohort), and no deaths within 30 days post-surgery.

All data analyses were performed by R software (version 4.1.0, http://www.r-project.org). Quantitative data conforming to a normal distribution were expressed as mean ± SD, while data not conforming to a normal distribution were presented as median [interquartile range]. Qualitative data were reported as numbers and percentages (n, %). Univariate logistic regression was conducted for each independent variable to evaluate its association with the dependent variable, producing odds ratios, confidence intervals, and P values. Variables with statistical significance (P ≤ 0.05) were selected for multivariate logistic regression, which assesses the effects of these variables while controlling for potential confounders. After multivariate regression analysis, variables with P values ≤ 0.05 were identified as independent influencing factors. The area under the curve (AUC) was used to evaluate the performance of the predictive model. The Xgboost package in R was employed to construct the XGBoost prediction model.

To enhance model interpretability, the SHAP algorithm was applied using the shapviz package. The SHAP algorithm enhances the interpretability of machine learning models by quantifying the contribution of each feature to individual predictions, using Shapley values derived from game theory. It calculates the marginal contributions of each feature to the prediction results. The SHAP value for each feature indicates its impact on a specific prediction: Positive values reflect an increase in the prediction, while negative values represent a decrease.

Among 376 patients, 287 were in the training group and 89 were in the validation group. Among all patients, 47 patients (12.5%) had perioperative blood transfusion, 18 patients (4.79%) had positive margins, 12 patients (3.19%) were readmitted within 30 days or perioperatively died, and 132 patients (35.11%) had prolonged hospitalization (Tables 1 and 2).

| Variables | Total (n = 287) | Textbook outcome (n = 150) | None-textbook outcome (n = 137) | P value |

| Age, M (Q1, Q3) | 56.00 (48.00, 63.00) | 55.00 (47.00, 62.00) | 59.00 (49.00, 63.00) | 0.118 |

| Sex | 0.011 | |||

| Male | 189 (65.85) | 109 (72.67) | 80 (58.39) | |

| Female | 98 (34.15) | 41 (27.33) | 57 (41.61) | |

| Hepatitis B | 0.002 | |||

| Negative | 179 (62.37) | 81 (54.00) | 98 (71.53) | |

| Positive | 108 (37.63) | 69 (46.00) | 39 (28.47) | |

| ECOG score | 0.026 | |||

| 0 | 85 (29.62) | 53 (35.33) | 32 (23.36) | |

| 1 | 202 (70.38) | 97 (64.67) | 105 (76.64) | |

| Child Pugh | 0.005 | |||

| A | 175 (60.98) | 80 (53.33) | 95 (69.34) | |

| B | 112 (39.02) | 70 (46.67) | 42 (30.66) | |

| Tumor size, M (Q1, Q3) | 6.40 (4.65, 8.90) | 6.10 (4.30, 8.40) | 7.00 (5.00, 9.20) | 0.098 |

| Tumor number | 0.870 | |||

| Solitary | 192 (66.90) | 101 (67.33) | 91 (66.42) | |

| Multiple | 95 (33.10) | 49 (32.67) | 46 (33.58) | |

| TBIL, M (Q1, Q3) | 20.00 (12.95, 31.90) | 22.90 (14.50, 32.90) | 17.10 (11.20, 28.10) | 0.013 |

| DBIL, M (Q1, Q3) | 7.90 (4.60, 14.75) | 8.85 (5.30, 15.45) | 7.30 (3.50, 14.40) | 0.012 |

| CA19-9, M (Q1, Q3) | 17.30 (8.95, 34.20) | 20.90 (13.90, 33.55) | 11.50 (3.90, 37.30) | < 0.001 |

| AFP, M (Q1, Q3) | 12.70 (3.30, 171.50) | 29.10 (3.62, 314.50) | 7.40 (3.20, 78.20) | 0.065 |

| CEA, M (Q1, Q3) | 2.60 (1.60, 4.10) | 2.45 (1.50, 4.00) | 2.60 (1.60, 4.60) | 0.219 |

| Blood transfusion | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 247 (86.06) | 150 (100.00) | 97 (70.80) | |

| Yes | 40 (13.94) | 0 (0.00) | 40 (29.20) | |

| Surgical margins | < 0.001 | |||

| Negative | 276 (96.17) | 150 (100.00) | 126 (91.97) | |

| Positive | 11 (3.83) | 0 (0.00) | 11 (8.03) | |

| Complications | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 227 (79.09) | 150 (100.00) | 77 (56.20) | |

| Yes | 60 (20.91) | 0 (0.00) | 60 (43.80) | |

| Perioperative death or readmission within 30 days after discharge | 0.008 | |||

| No | 279 (97.21) | 150 (100.00) | 129 (94.16) | |

| Yes | 8 (2.79) | 0 (0.00) | 8 (5.84) | |

| Prolonged hospitalization | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 187 (65.16) | 150 (100.00) | 37 (27.01) | |

| Yes | 100 (34.84) | 0 (0.00) | 100 (72.99) |

| Variables | Total (n = 89) | Textbook outcome (n = 49) | None-textbook outcome (n = 40) | P value |

| Age, M (Q1, Q3) | 58.00 (48.00, 65.00) | 59.00 (53.00, 64.00) | 56.50 (46.75, 65.00) | 0.501 |

| Sex | 0.167 | |||

| Male | 53 (59.55) | 26 (53.06) | 27 (67.50) | |

| Female | 36 (40.45) | 23 (46.94) | 13 (32.50) | |

| Hepatitis B | 0.190 | |||

| Negative | 64 (71.91) | 38 (77.55) | 26 (65.00) | |

| Positive | 25 (28.09) | 11 (22.45) | 14 (35.00) | |

| ECOG score | 0.001 | |||

| 0 | 32 (35.96) | 25 (51.02) | 7 (17.50) | |

| 1 | 57 (64.04) | 24 (48.98) | 33 (82.50) | |

| Child-Pugh | 0.017 | |||

| A | 57 (64.04) | 26 (53.06) | 31 (77.50) | |

| B | 32 (35.96) | 23 (46.94) | 9 (22.50) | |

| Tumor size, M (Q1, Q3) | 6.50 (5.00, 8.40) | 6.70 (4.70, 8.40) | 6.50 (5.00, 8.27) | 0.853 |

| Tumor number | 0.104 | |||

| Solitary | 66 (74.16) | 33 (67.35) | 33 (82.50) | |

| Multiple | 23 (25.84) | 16 (32.65) | 7 (17.50) | |

| TBIL, M (Q1, Q3) | 17.20 (10.70, 33.10) | 19.00 (10.60, 41.50) | 16.00 (11.18, 28.75) | 0.668 |

| DBIL, M (Q1, Q3) | 7.90 (4.60, 12.70) | 8.90 (5.10, 12.70) | 6.45 (4.33, 12.25) | 0.203 |

| CA19-9, M (Q1, Q3) | 109.10 (13.90, 778.00) | 192.70 (17.60, 1000.00) | 83.95 (8.10, 485.52) | 0.073 |

| AFP, M (Q1, Q3) | 6.20 (2.70, 97.60) | 5.10 (2.40, 97.60) | 6.95 (2.70, 74.53) | 0.738 |

| CEA, M (Q1, Q3) | 2.70 (1.80, 4.79) | 2.50 (1.70, 3.70) | 3.10 (2.00, 10.67) | 0.030 |

| Blood transfusion | 0.008 | |||

| No | 82 (92.13) | 49 (100.00) | 33 (82.50) | |

| Yes | 7 (7.87) | 0 (0.00) | 7 (17.50) | |

| Surgical margins | 0.008 | |||

| Negative | 82 (92.13) | 49 (100.00) | 33 (82.50) | |

| Positive | 7 (7.87) | 0 (0.00) | 7 (17.50) | |

| Complications | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 70 (78.65) | 49 (100.00) | 21 (52.50) | |

| Yes | 19 (21.35) | 0 (0.00) | 19 (47.50) | |

| Perioperative death or readmission within 30 days after discharge | 0.08 | |||

| No | 85 (95.51) | 48 (100.00) | 37 (90.00) | |

| Yes | 4 (4.49) | 0 (0.00) | 4 (10.00) | |

| Prolonged hospitalization | < 0.001 | |||

| No | 57 (64.04) | 49 (100.00) | 8 (20.00) | |

| Yes | 32 (35.96) | 0 (0.00) | 32 (80.00) |

Based on existing domestic and foreign research and previous clinical experience, 12 observation indicators were finally included for variable screening. Single-factor logistic regression showed that: Child-Pugh grade, ECOG score, hepatitis B, and tumor size were preoperative factors that affected the TO (P < 0.05). Multi-factor results showed that: Child-Pugh grade, ECOG score, hepatitis B, and tumor size were preoperative factors that affected the TO (P < 0.05), which were independent influencing factors that affect reaching the TO (Table 3).

| Characteristics | OR | 95%CI | P value | OR1 | 95%CI1 | P value1 |

| Female | 1.89 | 1.16-3.11 | 0.011 | 1.59 | 0.95-2.69 | 0.08 |

| Age | 1.01 | 0.99-1.03 | 0.41 | NA | NA | NA |

| Hepatitis B | 0.47 | 0.29-0.76 | 0.002 | 0.58 | 0.35-0.98 | 0.041 |

| Child-Pugh A | 0.51 | 0.31-0.82 | 0.006 | 0.5 | 0.3-0.83 | 0.007 |

| ECOG score = 1 | 1.79 | 1.07-3.01 | 0.027 | 1.9 | 1.1-3.28 | 0.022 |

| Tumor size | 1.08 | 1.01-1.17 | 0.032 | 1.09 | 1.01-1.18 | 0.036 |

| Multiple tumor | 1.04 | 0.64-1.7 | 0.87 | NA | NA | NA |

| AFP level | 1 | 1-1 | 0.486 | NA | NA | NA |

| CA19-9 level | 1 | 1-1 | 0.544 | NA | NA | NA |

| CEA level | 1 | 1-1 | 0.656 | NA | NA | NA |

| TBIL level | 1 | 0.99-1 | 0.228 | NA | NA | NA |

| DBIL level | 1 | 0.99-1 | 0.262 | NA | NA | NA |

We used the XGboost package in R language to build the XGboost prediction model. To facilitate subsequent model training and verification, we randomly divided the data into two parts, with 70% of the data serving as the training set and 30% as the validation set using an algorithm. The XGboost prediction model was established using the variables screened by logistic regression: Child-Pugh grade, ECOG score, hepatitis B, and tumor size. The results showed that the Xgboost model has good prediction effect in train group (AUC = 0.882) (Figure 1A) and validation group (AUC = 0.834) (Figure 1B).

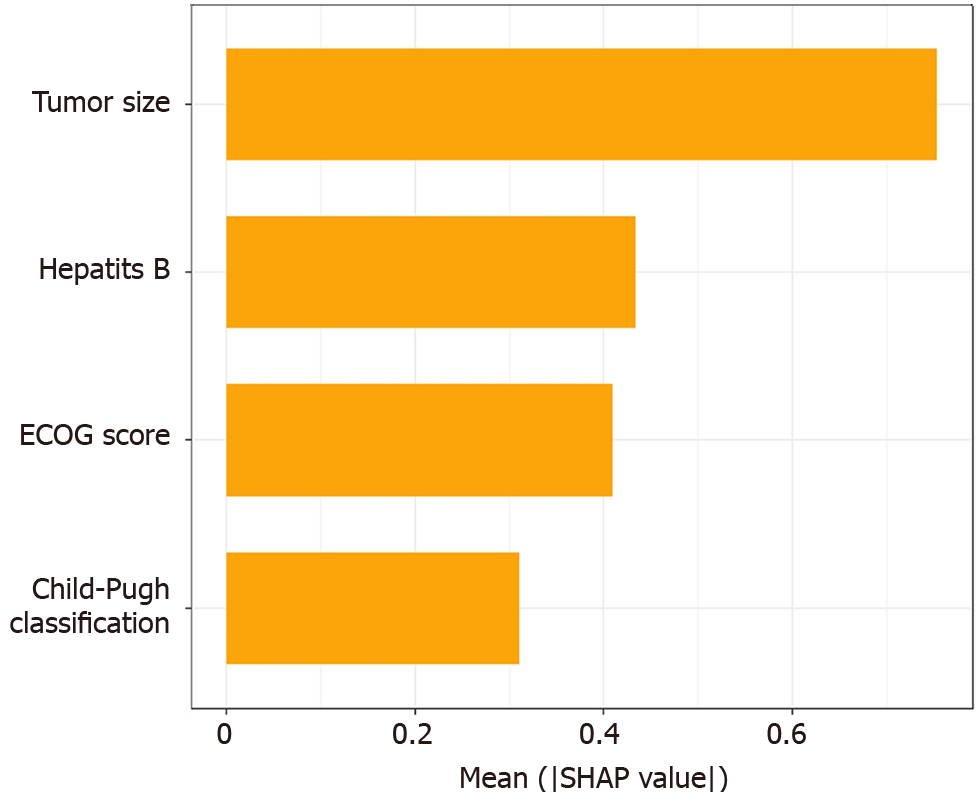

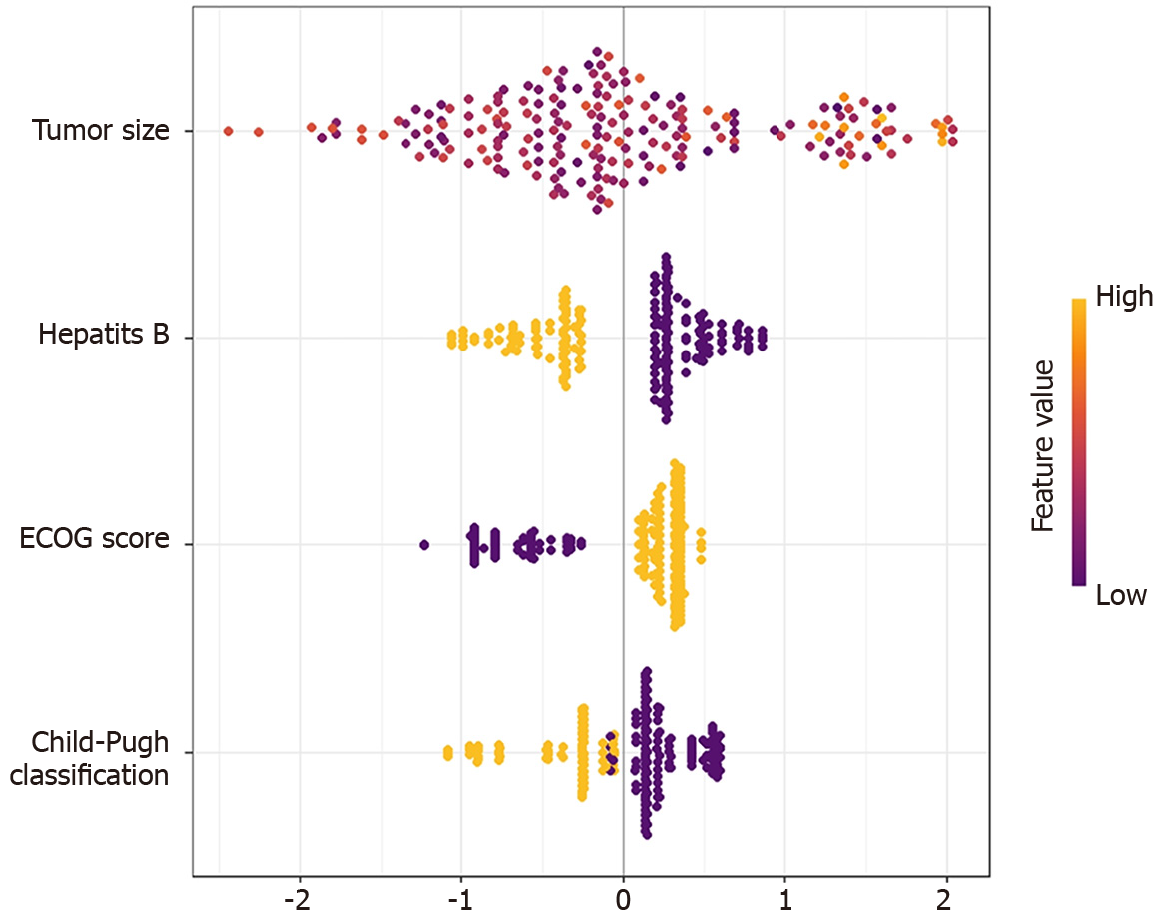

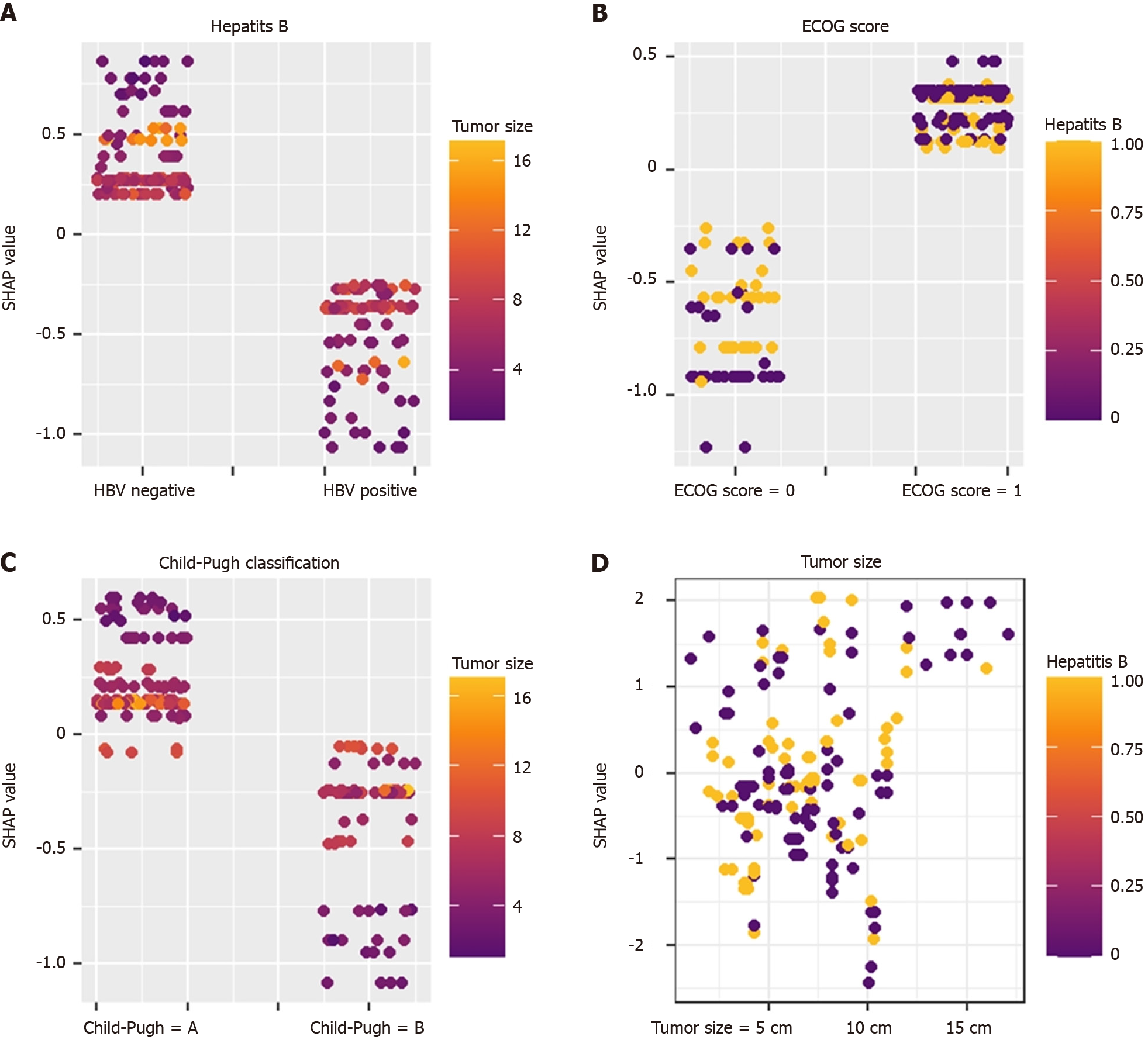

To make the XGboost model interpretable, we combine the SHAP algorithm with the XGboost model. In the overall visualization, the four variables were ranked in importance. The SHAP histogram shows that the variables with weights from high to low in the model are: Tumor size, Child-Pugh grade, hepatitis B, and ECOG score (Figure 2). In the SHAP bee swarm plot, each point represents the SHAP value of a sample (Figure 3). The color of the point represents the original value of the feature. Red represents high values and blue represents low values. The results show that tumor size has the most important impact on model prediction.

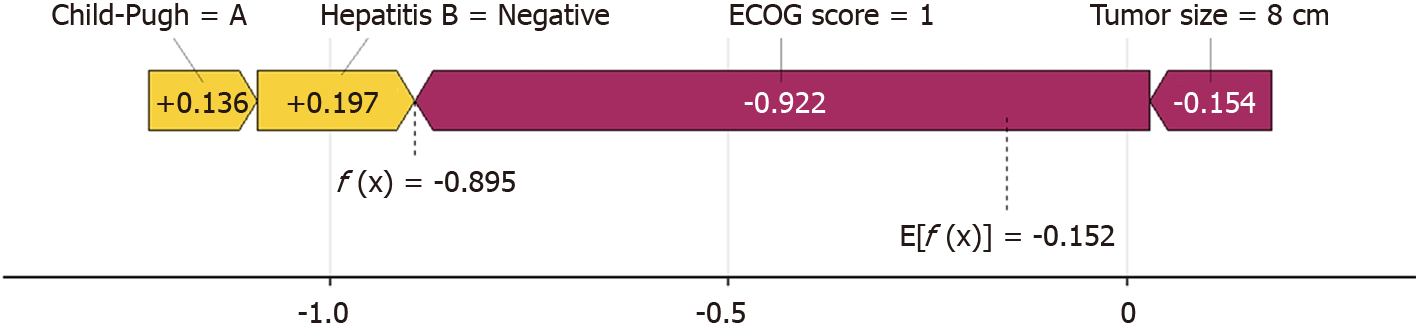

Figure 4 shows the prediction process of patients by the XGboost model. Taking No. 1 patient as an example, the patient has a tumor of 8 cm (-0.154), HBV negative (+0.197), and liver function Child A grade (+0.136). ECOG 0 points

SHAP values and scatter point colors reflect the influence relationship between variables. Different features interact with each other to predict the TO. For example: In hepatitis B-negative patients, the smaller the tumor, the higher the SHAP value, indicating that in hepatitis B-negative patients, the smaller the tumor, the easier it is to achieve the TO (Figure 5).

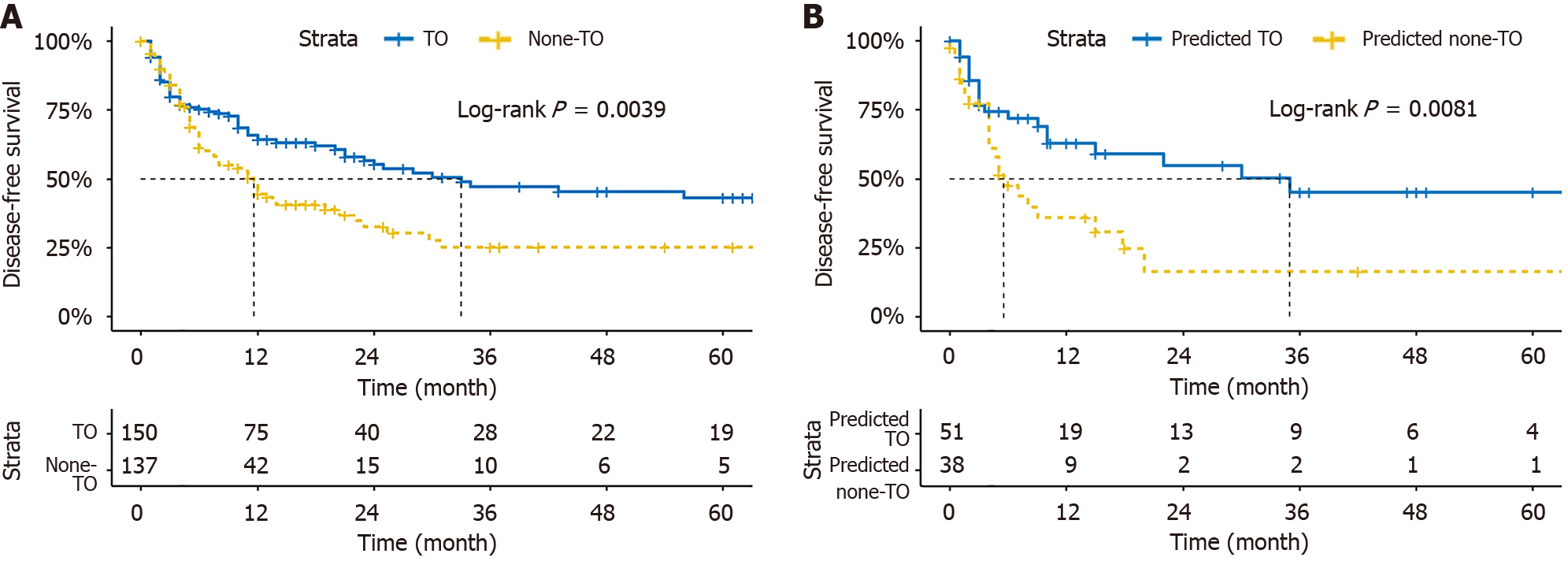

Survival analysis shows that the DFS of patients reaching the TO in 1, 2, and 3 years were 64.2%, 56.8%, and 43.4%. The DFS of patients that did not meet the TO in 1, 2, and 3 years were 44.7%, 32.5%, and 25.2%. There was a difference in DFS between the two groups (P < 0.05; Figure 6A). In order to evaluate the impact of the model prediction results on prognosis, patients were divided into the predicted TO group and the predicted not to meet the TO group based on the model prediction results. The results showed that the predicted outcomes were successfully stratify DFS (Figure 6B).

Achieving TO may improve patient survival and DFS and serves as an effective indicator of medical quality[24]. In this study, we used logistic regression to screen influencing factors based on 12 preoperative clinical indicators and developed a predictive model using machine learning algorithms. An XGBoost preoperative prediction model with high accuracy was trained, and the SHAP algorithm was employed to visualize the model. This approach intuitively demonstrated the prediction process from individual cases to overall trends, thereby elucidating the previously opaque operations of machine learning.

Postoperative complications and prolonged hospital stays are the main challenges faced by patients after surgery. In this study, 21.01% of patients experienced complications postoperatively. These complications can prolong hospital stays and reduce quality of life[25]. Some studies have shown that older age, cirrhosis, and low liver reserve function are potential risk factors for complications[14,26]. Therefore, identifying high-risk patients and implementing early intervention strategies may reduce complications and improve the rate of achieving TO. The median hospitalization time in this study was 10 days, and prolonged hospital stays were associated with complications and poor postoperative recovery[27]. Active preoperative preparation and the adoption of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols may help reduce hospitalization durations[28-30], thereby increasing the proportion of patients achieving TO.

Our study identified several preoperative factors influencing the achievement of TO, including Child-Pugh classification, ECOG score, hepatitis B, and tumor size. Child-Pugh classification is an important indicator of liver reserve function[31]. Patients with poor liver reserve and low compensatory ability are more likely to experience postoperative complications and delayed recovery. Some studies have demonstrated the prognostic significance of the preoperative Child-Pugh classification[32] and highlighted the higher risk of complications after lymph node dissection (LND) in patients with liver cirrhosis[25]. The ECOG score is another key indicator of a patient's general health and daily functioning[33]. It has been used as a prognostic factor in several studies[34]. Accurate preoperative assessment of the ECOG score can provide valuable guidance for predicting postoperative outcomes. Hepatitis B is a major contributor to the development of ICC. Surgery and postoperative adjuvant therapy can potentially reactivate the hepatitis B virus, negatively affecting both short-term and long-term prognoses[35]. Research suggests that standardized preoperative and postoperative antiviral treatments can improve surgical outcomes and patient survival[36,37]. Tumor size is an independent risk factor affecting patient prognosis. Larger tumors are associated with more complex surgeries, longer operation times, and a higher likelihood of complications and surgical accidents[7]. Some studies have pointed out that larger tumors tend to exhibit lymph node involvement, which can increase surgical time and complications[38]. Our findings underscore the importance of early detection, diagnosis, and treatment to improve outcomes for patients with smaller tumors.

Preoperative judgment of the patient’s post-operative status is particularly important for perioperative preparation and accident prevention[39]. Predicting whether a patient will achieve TO prior to surgery can boost surgeons' confidence and guide preoperative planning. Conversely, identifying patients unlikely to achieve TO preoperatively can prompt enhanced preparations and more cautious surgical approaches. While many predictive models have been developed to assess the prognosis of ICC patients[40], most focus on postoperative pathological factors. This study addresses a gap by establishing a machine learning model to predict postoperative status and short-term outcomes using the composite TO index. By incorporating the SHAP algorithm, we addressed the interpretability challenge of machine learning models, enabling clinicians to more intuitively evaluate the likelihood of achieving TO. Furthermore, DFS analysis revealed that patients achieving TO had better DFS outcomes than those who did not, consistent with prior research[41]. Achieving TO benefits patients not only in the short term but also by delaying tumor recurrence.

This study has certain limitations. As a retrospective study, selection bias is inevitable. Additionally, the number of variables included was relatively small, and factors such as preoperative body mass index, hypertension, and diabetes were not considered. Including these variables could improve model accuracy and will be an avenue for future research. Furthermore, the high prevalence of hepatitis B in China may limit the model's generalizability to other populations. Expanding the sample size to include Western populations will be essential for future studies. Lastly, our study could not clarify the relationship between tumor size and hepatitis B status. Previous studies suggest that a tumor size cutoff of 5 cm stratifies prognosis in hepatitis B-related liver cancer, but this correlation has not been observed in non-hepatitis B patients[42]. HBV-associated ICC may originate from hepatocytes, leading to lower invasiveness and a better prognosis[43]. However, the impact of tumor size in this context remains uncertain and warrants further investigation.

It is important to emphasize that failure to achieve TO does not imply inadequate treatment. Similarly, preoperative predictions of failure to achieve TO do not mean patients have lost their chances of survival. Physicians should provide extra attention and care to patients predicted to fall short of achieving TO, striving to increase the proportion of patients reaching this benchmark.

The machine learning model predicts TO with good accuracy, and the DFS of patients who achieve the TO is better than that of patients who do not. The SHAP algorithm enables the visualization of the machine learning prediction model.

| 1. | Bridgewater J, Galle PR, Khan SA, Llovet JM, Park JW, Patel T, Pawlik TM, Gores GJ. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;60:1268-1289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 862] [Cited by in RCA: 1073] [Article Influence: 97.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Deng L, Chen B, Zhan C, Yu H, Zheng J, Bao W, Deng T, Zheng C, Wu L, Yang Y, Yu Z, Wang Y, Chen G. A Novel Clinical-Radiomics Model Based on Sarcopenia and Radiomics for Predicting the Prognosis of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma After Radical Hepatectomy. Front Oncol. 2021;11:744311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Razumilava N, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet. 2014;383:2168-2179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1072] [Cited by in RCA: 1378] [Article Influence: 125.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | A S, Wu H, Wang X, Wang X, Yang J, Xia L, Xia Y. Value of glycogen synthase 2 in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma prognosis assessment and its influence on the activity of cancer cells. Bioengineered. 2021;12:12167-12178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nathan H, Pawlik TM, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Cameron JL, Schulick RD. Trends in survival after surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: a 30-year population-based SEER database analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1488-1496; discussion 1496. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 10.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kelley RK, Bridgewater J, Gores GJ, Zhu AX. Systemic therapies for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatol. 2020;72:353-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 279] [Article Influence: 55.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Kawashima J, Sahara K, Shen F, Guglielmi A, Aldrighetti L, Weiss M, Bauer TW, Alexandrescu S, Poultsides GA, Maithel SK, Marques HP, Martel G, Pulitano C, Cauchy F, Koerkamp BG, Matsuyama R, Endo I, Pawlik TM. Predicting risk of recurrence after resection of stage I intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2024;28:18-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Chun YS, Javle M. Systemic and Adjuvant Therapies for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancer Control. 2017;24:1073274817729241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 83] [Article Influence: 11.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mavros MN, Economopoulos KP, Alexiou VG, Pawlik TM. Treatment and Prognosis for Patients With Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Surg. 2014;149:565-574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 641] [Cited by in RCA: 594] [Article Influence: 54.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Holzner ML, Mazzaferro V, Busset MDD, Aldrighetti L, Ratti F, Hasegawa K, Arita J, Sapisochin G, Abreu P, Schoning W, Schmelzle M, Nevermann N, Pratschke J, Florman S, Halazun K, Schwartz ME, Tabrizian P. Is Repeat Resection for Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma Warranted? Outcomes of an International Analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:4397-4404. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shen Z, Tao L, Cai J, Zheng J, Sheng Y, Yang Z, Gong L, Song C, Gao J, Ying H, Xu J, Liang X. Safety and feasibility of laparoscopic liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a propensity score-matched study. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Xu L, Shao Z, Huang H, Li D, Wang T, Atyah M, Zhou W, Yang Z. Impact of Frailty on Short-Term Outcomes of Hepatic Lobectomy in Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: Evidence from the US Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2005-2018. Dig Surg. 2024;41:42-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kim KD, Lee JE, Kim J, Ro J, Rhu J, Choi GS, Heo JS, Joh JW. Laparoscopic liver resection as a treatment option for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Updates Surg. 2024;76:869-878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Endo Y, Moazzam Z, Woldesenbet S, Araujo Lima H, Alaimo L, Munir MM, Shaikh CF, Guglielmi A, Aldrighetti L, Weiss M, Bauer TW, Alexandrescu S, Poultsides GA, Kitago M, Maithel SK, Marques HP, Martel G, Pulitano C, Shen F, Cauchy F, Koerkamp BG, Endo I, Pawlik TM. Predictors and Prognostic Significance of Postoperative Complications for Patients with Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg. 2023;47:1792-1800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pavicevic S, Reichelt S, Uluk D, Lurje I, Engelmann C, Modest DP, Pelzer U, Krenzien F, Raschzok N, Benzing C, Sauer IM, Stintzing S, Tacke F, Schöning W, Schmelzle M, Pratschke J, Lurje G. Prognostic and Predictive Molecular Markers in Cholangiocarcinoma. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hobeika C, Cauchy F, Fuks D, Barbier L, Fabre JM, Boleslawski E, Regimbeau JM, Farges O, Pruvot FR, Pessaux P, Salamé E, Soubrane O, Vibert E, Scatton O; AFC-LLR-2018 study group. Laparoscopic versus open resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: nationwide analysis. Br J Surg. 2021;108:419-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Merath K, Chen Q, Bagante F, Alexandrescu S, Marques HP, Aldrighetti L, Maithel SK, Pulitano C, Weiss MJ, Bauer TW, Shen F, Poultsides GA, Soubrane O, Martel G, Koerkamp BG, Guglielmi A, Itaru E, Cloyd JM, Pawlik TM. A Multi-institutional International Analysis of Textbook Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Curative-Intent Resection of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2019;154:e190571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Xu Z, Lv Y, Zou H, Jia Y, Du W, Lu J, Liu Y, Shao Z, Zhang H, Sun C, Zhu C. Textbook outcome of laparoscopic hepatectomy in the context of precision surgery: A single center experience. Dig Liver Dis. 2024;56:1368-1374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Atyah MM, Xu L, Yang Z. Novel definition of textbook outcome in biliary system cancers and its influence on patients' survival and quality of life. Cancer Med. 2024;13:e7186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bobrzynski L, Sędłak K, Rawicz-Pruszyński K, Kolodziejczyk P, Szczepanik A, Polkowski W, Richter P, Sierzega M. Evaluation of optimum classification measures used to define textbook outcome among patients undergoing curative-intent resection of gastric cancer. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:1199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhu J, Wang D, Liu C, Huang R, Gao F, Feng X, Lan T, Li H, Wu H. Development and validation of a new prognostic immune-inflammatory-nutritional score for predicting outcomes after curative resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A multicenter study. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1165510. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Xin HY, Zou JX, Sun RQ, Hu ZQ, Chen Z, Luo CB, Zhou ZJ, Wang PC, Li J, Yu SY, Liu KX, Fan J, Zhou J, Zhou SL. Characterization of tumor microbiome and associations with prognosis in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Gastroenterol. 2024;59:411-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fiz F, Rossi N, Langella S, Conci S, Serenari M, Ardito F, Cucchetti A, Gallo T, Zamboni GA, Mosconi C, Boldrini L, Mirarchi M, Cirillo S, Ruzzenente A, Pecorella I, Russolillo N, Borzi M, Vara G, Mele C, Ercolani G, Giuliante F, Cescon M, Guglielmi A, Ferrero A, Sollini M, Chiti A, Torzilli G, Ieva F, Viganò L. Radiomics of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma and Peritumoral Tissue Predicts Postoperative Survival: Development of a CT-Based Clinical-Radiomic Model. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:5604-5614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Tsilimigras DI, Sahara K, Moris D, Mehta R, Paredes AZ, Ratti F, Marques HP, Soubrane O, Lam V, Poultsides GA, Popescu I, Alexandrescu S, Martel G, Workneh A, Guglielmi A, Hugh T, Aldrighetti L, Weiss M, Bauer TW, Maithel SK, Pulitano C, Shen F, Koerkamp BG, Endo I, Pawlik TM. Assessing Textbook Outcomes Following Liver Surgery for Primary Liver Cancer Over a 12-Year Time Period at Major Hepatobiliary Centers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:3318-3327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhou YM, Sui CJ, Zhang XF, Li B, Yang JM. Influence of cirrhosis on long-term prognosis after surgery in patients with combined hepatocellular-cholangiocarcinoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2017;17:25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Kauppila JH, Johar A, Lagergren P. Postoperative Complications and Health-related Quality of Life 10 Years After Esophageal Cancer Surgery. Ann Surg. 2020;271:311-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Aliseda D, Sapisochin G, Martí-Cruchaga P, Zozaya G, Blanco N, Goh BKP, Rotellar F. Association of Laparoscopic Surgery with Improved Perioperative and Survival Outcomes in Patients with Resectable Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis from Propensity-Score Matched Studies. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:4888-4901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Peng LH, Wang WJ, Chen J, Jin JY, Min S, Qin PP. Implementation of the pre-operative rehabilitation recovery protocol and its effect on the quality of recovery after colorectal surgeries. Chin Med J (Engl). 2021;134:2865-2873. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wang LH, Zhu RF, Gao C, Wang SL, Shen LZ. Application of enhanced recovery after gastric cancer surgery: An updated meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:1562-1578. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Huang Y, Xie Q, Wei X, Shi Q, Zhou Q, Leng X, Miao Y, Han Y, Wang K, Fang Q. Enhanced Recovery Protocol Versus Conventional Care in Patients Undergoing Esophagectomy for Cancer: Advantages in Clinical and Patient-Reported Outcomes. Ann Surg Oncol. 2024;31:5706-5716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Wen X, Yao M, Lu Y, Chen J, Zhou J, Chen X, Zhang Y, Lu W, Qian X, Zhao J, Zhang L, Ding S, Lu F. Integration of Prealbumin into Child-Pugh Classification Improves Prognosis Predicting Accuracy in HCC Patients Considering Curative Surgery. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2018;6:377-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Li H, Li J, Wang J, Liu H, Cai B, Wang G, Wu H. Assessment of Liver Function for Evaluation of Long-Term Outcomes of Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: A Multi-Institutional Analysis of 620 Patients. Front Oncol. 2020;10:525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, Horton J, Davis TE, Mcfadden ET, Carbone PP. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7038] [Cited by in RCA: 8003] [Article Influence: 190.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Garajová I, Gelsomino F, Salati M, Mingozzi A, Peroni M, De Lorenzo S, Granito A, Tovoli F, Leonardi F. Second-Line Chemotherapy for Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinomas: What Is the Real Gain? Life (Basel). 2023;13:2170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Huang G, Lai EC, Lau WY, Zhou WP, Shen F, Pan ZY, Fu SY, Wu MC. Posthepatectomy HBV reactivation in hepatitis B-related hepatocellular carcinoma influences postoperative survival in patients with preoperative low HBV-DNA levels. Ann Surg. 2013;257:490-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Liang Y, Zhong D, Zhang Z, Su Y, Yan S, Lai C, Yao Y, Shi Y, Huang X, Shang J. Impact of preoperative antiviral therapy on the prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2024;24:291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang XH, Hu ZL, Fu YZ, Hou JY, Li WX, Zhang YJ, Xu L, Zhou QF, Chen MS, Zhou ZG. Tenofovir vs. entecavir on prognosis of hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. J Gastroenterol. 2022;57:185-198. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chen YX, Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Fan J, Zhou J, Jiang W, Zeng MS, Tan YS. Prediction of the lymph node status in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of 320 surgical cases. Front Oncol. 2011;1:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Guo SB, Hu LS, Huang WJ, Zhou ZZ, Luo HY, Tian XP. Comparative investigation of neoadjuvant immunotherapy versus adjuvant immunotherapy in perioperative patients with cancer: a global-scale, cross-sectional, and large-sample informatics study. Int J Surg. 2024;110:4660-4671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Mashiko T, Carreras J, Ogasawara T, Masuoka Y, Ei S, Takahashi S, Nomura T, Mori M, Koyanagi K, Yamamoto S, Nakamura N, Nakagohri T. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma with arterial phase hyperenhancement and specialized tumor microenvironment associated with good prognosis after radical resection: A single-center retrospective study. Surgery. 2024;176:259-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Clocchiatti L, Marino R, Ratti F, Pedica F, Casadei Gardini A, Lorenzin D, Aldrighetti L. Defining and predicting textbook outcomes for perihilar cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of factors improving achievement of desired postoperative outcomes. Int J Surg. 2024;110:209-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Hwang S, Lee YJ, Kim KH, Ahn CS, Moon DB, Ha TY, Song GW, Jung DH, Lee SG. The Impact of Tumor Size on Long-Term Survival Outcomes After Resection of Solitary Hepatocellular Carcinoma: Single-Institution Experience with 2558 Patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2015;19:1281-1290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Song Z, Lin S, Wu X, Ren X, Wu Y, Wen H, Qian B, Lin H, Huang Y, Zhao C, Wang N, Huang Y, Peng B, Li X, Peng H, Shen S. Hepatitis B virus-related intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma originates from hepatocytes. Hepatol Int. 2023;17:1300-1317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |