Published online Mar 7, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i9.1143

Peer-review started: December 1, 2023

First decision: January 4, 2024

Revised: January 4, 2024

Accepted: February 2, 2024

Article in press: February 2, 2024

Published online: March 7, 2024

Processing time: 95 Days and 14.9 Hours

Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) of gastric submucosal tumors (SMTs) is safe and effective; however, postoperative wound management is equally important. Literature on suturing following EFTR for large (≥ 3 cm) SMTs is scarce and limited.

To evaluate the efficacy and clinical value of double-nylon purse-string suture in closing postoperative wounds following EFTR of large (≥ 3 cm) SMTs.

We retrospectively analyzed the data of 85 patients with gastric SMTs in the fundus of the stomach or in the lesser curvature of the gastric body whose wounds were treated with double-nylon purse-string sutures after successful tumor resection at the Endoscopy Center of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University. The operative, postoperative, and follow-up conditions of the patients were evaluated.

All tumors were completely resected using EFTR. 36 (42.35%) patients had tumors located in the fundus of the stomach, and 49 (57.65%) had tumors located in the body of the stomach. All patients underwent suturing with double-nylon sutures after EFTR without laparoscopic assistance or further surgical treatment. Postoperative fever and stomach pain were reported in 13 (15.29%) and 14 (16.47%) patients, respectively. No serious adverse events occurred during the intraoperative or postoperative periods. A postoperative review of all patients revealed no residual or recurrent lesions.

Double-nylon purse-string sutures can be used to successfully close wounds that cannot be completely closed with a single nylon suture, especially for large (≥ 3 cm) EFTR wounds in SMTs.

Core Tip: This study aimed to evaluate the clinical value of double-nylon purse-string sutures in closing gastric defects following submucosal tumor treatment with endoscopic full-thickness resection. Findings revealed that gastric wall defects were successfully closed using double-nylon purse-string sutures in patients with a tumor (≥ 3 cm), without laparoscopic assistance or need for further surgical treatment. There was also no recurrence or residue of lesions in all participants. We believe that our study makes a significant contribution to the literature because it evaluates the safety and short-term efficacy of a novel closure method in gastrointestinal endoscopy.

- Citation: Wang SS, Ji MY, Huang X, Li YX, Yu SJ, Zhao Y, Shen L. Double-nylon purse-string suture in closing postoperative wounds following endoscopic resection of large (≥ 3 cm) gastric submucosal tumors. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(9): 1143-1153

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i9/1143.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i9.1143

Submucosal neoplasms (SMTs) are tumors that occur in the lower layer of the gastrointestinal mucosa[1]. Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) is increasingly used in patients with deep lesions, such as SMTs, because it results in minimal trauma and preserves the original anatomy and function of the stomach[2,3]. EFTR can be regarded as the “last resort” for endoscopic treatment, similar to surgical resection, which can treat deeper lesions and make histological assessment more complete[4]. However, when treating patients with SMTs with EFTR, the lesion is removed entirely through “active perforation”[5]. Consequently, the surface of the wound needs to be sutured after tumor removal. After tumor resection with EFTR, the most critical issue is complete closure of the gastric wall defect, which is also the primary safety concern for the clinical implementation of EFTR. Incomplete closure may lead to a higher rate of late perforation and the need for further surgical repair.

In recent years, various closure techniques, including wound clipping, endoscopic stapling, endoscopic full-layer folding systems, over-the-scope clip (OTSC) systems, OverstitchTM endoscopic suturing systems, and bioabsorbable fillers, have been used to suture gastric wall defects after EFTR[6-9]. Some of these closure methods are simple but cannot achieve complete closure of large gastric wall perforations. However, other endoscopic devices are relatively expensive and challenging to operate, preventing their widespread use in medical institutions.

In the absence of special devices or equipment, endoscopists in our endoscopy center practice using a double-nylon rope for purse-string sutures based on the single-nylon rope purse-string suture technique for large (≥ 3 cm) SMTs. This study aimed to analyze the safety and short-term efficacy of this novel closure method.

This was a retrospective single-arm clinical trial. The patient inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Having a tumor located in the stomach and confirmed to originate from the muscularis propria on endoscopic ultrasonography; (2) having a tumor diameter ≥ 3 cm and no adhesion between the tumor and peritoneal tissues or organs, as confirmed by ultrasonic endoscopy and computed tomography; (3) having no malignancy according to endoscopic ultrasonography, such as an irregular boundary, numerous blood vessels, ulcers on the surface, a strong echo focal area, or uneven echoes under endoscopic ultrasonography; and (4) being able to tolerate tracheal intubation anesthesia, with no coagulation dysfun

One of the authors (Wang SS) independently analyzed patient medical records from our hospital's endoscopy database as part of a quality assurance program. Between June 2019 and June 2022, 128 patients with large (≥ 3 cm) upper gastrointestinal SMTs underwent resection, performed by the same endoscopist, as well as closure using a double-nylon purse-string suture at our endoscopy center. Based on the tumor site, we included 36 patients with gastric fundus SMTs and 49 with gastric body lesser curvature SMTs.

All included patients provided informed consent after receiving detailed explanations regarding the endoscopic resection procedure and other possible treatment options. Furthermore, all patients were informed that surgery might be required if the tumor could not be removed en bloc endoscopically and that severe complications might not be managed conservatively or via endoscopic methods. The primary outcome measures were: (1) Complete resection; (2) complete wound closure; and (3) postoperative complications.

Gastroscope (GIF-Q260J, Olympus, Japan), electronic endoscopy system (Olympus-LUCERA CV-290), high-frequency electric coagulation and electrocution device (ERBE VIO-200D), disposable high-frequency therapeutic forceps (FD-410 LR), hooking knife (Olympus), IT knife, dual knife, titanium clip release device (Olympus), snares, nylon ropes (MAJ340, MAJ254, Olympus), and CO2 air pump were used. A transparent cap (D-201 series) was joined at the end of the endoscope during the treatment.

Within this study, the selection of employing double-nylon to strengthen the purse suture was determined by the wound condition after the single-nylon purse-string suture. Factors taken into consideration encompassed intraoperative sutures, creases, tension, and other pertinent variables.

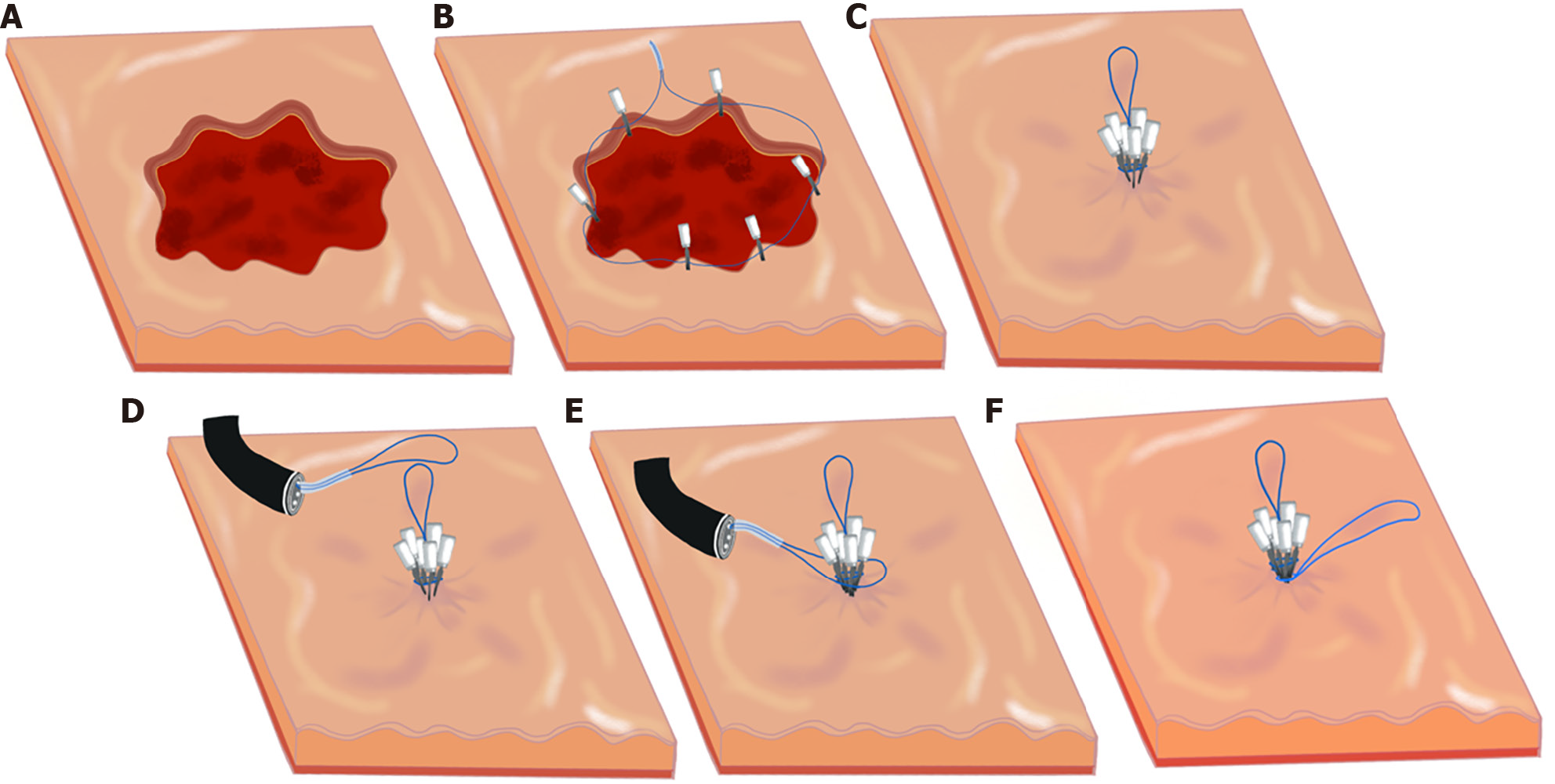

The whole endoscopic procedure consisted of six main steps: (1) The location of the tumor was confirmed under endoscopic guidance, and the mucosa was incised to reveal the lesion; (2) Complete resection of the tumor through EFTR; (3) Wound treatment, observation, and evaluation of the gastric wall defect; (4) The gastric wall defect was closed with a single-nylon rope “purse-string suture;” (5) A second nylon rope was inserted to reinforce and close the treated wound again; and (6) The endoscope was removed after confirming satisfactory closure, and the surgery was completed.

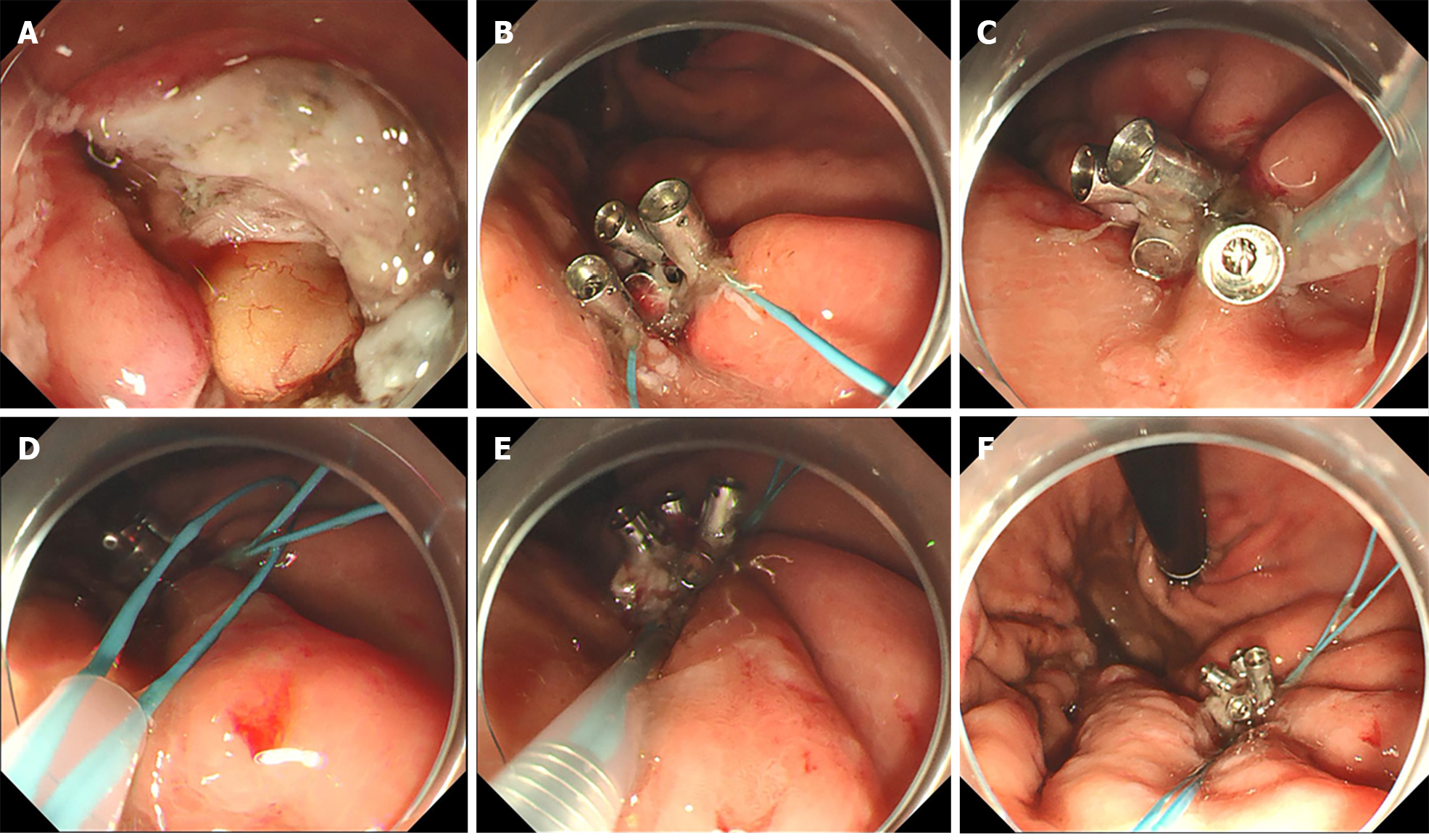

The process of executing double-nylon purse-string sutures was as follows (Figures 1 and 2): (1) The nylon rope was clamped using foreign body forceps inserted in the stomach cavity along with the endoscope and placed at the wound. The foreign body clamp was removed, and the titanium clamp was pushed through the biopsy channel. A titanium clip was used to clamp the distal end of the nylon rope on the normal mucosal tissue around the wound. The titanium clips were continued to be fixed around the wound in an annular shape at equal distances. The nylon-string outer casing was pushed forward, keeping the titanium clips vertical. The nylon rope was tightened to close the wound’s distal and proximal gastric wall. The procedure of single-nylon purse-string sutures can be seen in our previous study[10]; (2) The second nylon rope was advanced through the biopsy channel into the stomach cavity. Care was taken that the second nylon rope could wrap around the wound closure and all titanium clips; (3) The nylon loop was pushed down to tighten the nylon rope. Whenever it was found that the nylon rope might slip from the holding place of the titanium clip, the position of the titanium clip was adjusted using the foreign body forceps to help the nylon rope reach the base of the wound; and (4) When the position of the second nylon rope was correct and not easy to move, the nylon rope was tightened to complete the secondary closure of the wound. Finally, the stomach was injected with CO2 to observe whether the stomach cavity was inflated and filled to evaluate the success of the perforation closure. This closure process can be summarized as two main steps: (1) The initial closure of the wound surface using the single-nylon rope and the titanium clip; and (2) the reinforcement and closure of the second nylon rope.

The operation and closure times and patient conditions during follow-up were observed. The operative time refers to the duration of the entire tumor extraction process. The closure time was defined as the interval between the commencement of nylon rope and titanium clip insertion and the culmination of the tightening of the second nylon rope.

After fixation, the excised lesions were delivered to the pathology department for pathological characterization and immunohistochemical examination. The patients were asked to avoid eating or drinking within 72 h after surgery. The patients’ vital signs and symptoms, such as fever, abdominal pain, melena, and peritonitis, were closely monitored. Concurrently, standard measures were implemented, including gastrointestinal decompression, conventional fluid infusion, and oral administration of proton pump inhibitors, hemostatics, antibiotics, and gastric mucosal protective drugs. Gastroscopy was scheduled at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively, followed by annual examinations.

The primary outcome was the success rate of purse suturing using nylon ropes and titanium clips in all patients and whether all the tumors were resected and removed. The secondary outcomes were the total operation time and treatment outcomes (fever, abdominal pain, delayed perforation, and mean length of hospital stay) in EFTR patients. These endpoints were also compared between the two groups and subgroups. We selected lesion location and diameter for further subgroup analyses.

The data were analyzed using SPSS software (version 23.0; IBM SPSS Inc., Armonk, NY, United States). Statistical data are expressed as percentages (%), and the χ2 test was used to compare the groups. The data are expressed as the mean ± SD, and the groups were compared using the T-test. Significance was set at P < 0.05.

The maximum diameter of the lesions was 5.0 cm (3.63 ± 0.54 cm). Tumors in all 85 patients were completely resected using EFTR. The gastric wall defects were successfully closed using double-nylon purse-string sutures (Figure 2). All procedures were completed under endoscopic guidance without laparoscopic assistance or transfer to surgery for further treatment. The mean operative time was 69.63 ± 21.09 min, the mean single-nylon rope closure time was 26.73 ± 6.89 min, and the mean second nylon rope reinforcement time was 5.98 ± 1.67 min. Six titanium clips were used in 41 (41/85, 48.24%) patients; seven, in 31 (31/85, 37.65%) patients; eight, in 10 (10/85, 11.76%) patients; and nine, in 2 (2/85, 2.35%) patients. Pathology revealed complete resection of the tumor and no apparent disruption of the tumor capsule. There were 59 cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (52 cases of fusiform cell type and seven cases of mixed type), 23 cases of leiomyomas, and three cases of schwannomas. No serious adverse events occurred intra- or postoperatively. The patients were discharged after an average of 6.6 ± 0.74 d postoperatively (Table 1).

| Total population, n = 85 | |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 33 (38.82) |

| Female | 52 (61.18) |

| Location of the lesion, n (%) | |

| Fundus of the stomach | 36 (42.35) |

| Body of the stomach | 49 (57.65) |

| Lesion size, n (%) | |

| ≥ 3 cm, < 4 cm | 58 (68.24) |

| ≥ 4 cm, < 5 cm | 27 (31.76) |

| Mean (cm) | 3.63 ± 0.54 |

| Histopathology, n (%) | |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | 59 (69.41) |

| Fusiform cell type | 52 |

| Mixed type | 7 |

| Leiomyoma | 23 (27.06) |

| Neurilemmoma | 3 (3.53) |

| Operation time | |

| < 60 min | 26 (30.59) |

| ≥ 60 min, < 120 min | 57 (67.06) |

| ≥ 120 min | 2 (2.35) |

| Mean (min) | 69.63 ± 21.09 |

| Closure time | |

| < 20 min | 12 (14.1) |

| ≥ 20 min, < 30 min | 44 (51.762) |

| ≥ 30 min | 29 (34.12) |

| Mean (min) | 26.73 ± 6.89 |

| Closure time, second nylon rope purse-string suture | |

| < 5 min | 15 (17.65) |

| ≥ 5 min, < 10 min | 67 (78.82) |

| ≥ 10 min | 3 (3.53) |

| Mean (min) | 5.98 ± 1.67 |

| The number of metal titanium clips | |

| 6 | 41 (48.24) |

| 7 | 32 (37.65) |

| 8 | 10 (11.76) |

| 9 | 2 (2.35) |

| Mean | 6.68 ± 0.77 |

| Adverse event, n (%) | |

| Low fever | 13 (15.29) |

| Abdominal pain | 14 (16.47) |

| Postoperative hospital stays | |

| Mean (d) | 6.6 ± 0.74 |

| Residual apparatus after operation, n (%) | |

| 3 months | 28 (32.94) |

| 6 months | 13 (15.29) |

| 12 months | 4 (4.71) |

Bleeding was the main intraoperative adverse event associated with EFTR. Intraoperative bleeding was observed in all patients, and hemostasis was successfully achieved. No postoperative bleeding was observed. Postoperative abdominal pain and fever were defined as mild complications, and none of the patients experienced severe complications. Postoperatively, 13 patients developed a low fever. Antibiotic treatment and gastrointestinal decompression were administered, and the patients were strictly confined to bed rest. The body temperature returned to normal on the second day postoperatively. Fourteen patients experienced mild pain in the upper abdomen postoperatively. Whenever necessary, abdominal ultrasound B was performed to determine whether the patient had exudation in the abdominal cavity. Through timely blood analysis and monitoring of vital signs, we observed independent resolution of the abdominal pain.

We selected the lesion location (fundus vs stomach body) for further subgroup analyses (Table 2). Notably, no significant differences were observed between the fundus subgroup and the stomach-body subgroup regarding postoperative complications, operative time, closure time, number of metal titanium clips, or postoperative hospital stay (P > 0.05). We also performed a subgroup analysis based on tumor diameter (< 4 cm vs ≥ 4 cm) (Table 3). In the diameter subgroup analysis, there were significant differences in postoperative abdominal pain (P = 0.011), low fever (P = 0.005), operative time (P = 0.000), number of metal titanium clips (P = 0.000), and length of postoperative hospital stay (P = 0.019). Conversely, no significant differences were observed between the diameter subgroups regarding the single-nylon rope purse-string suture time or the second nylon rope reinforcement time (P > 0.05).

| Fundus of the stomach, n = 36 | Body of the stomach, n = 49 | P value | |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 | |

| Abdominal pain | 7 | 7 | 0.526 |

| Low fever | 6 | 7 | 0.763 |

| Operation time | |||

| Mean (min) | 69.95 ± 15.72 | 69.41 ± 24.29 | 0.398 |

| Closure time, single-nylon rope purse-string suture | |||

| Mean (min) | 25.89 ± 6.19 | 27.35 ± 7.30 | 0.456 |

| Closure time, second nylon rope purse-string suture | |||

| Mean (min) | 6.22 ± 1.38 | 5.96 ± 1.31 | 0.437 |

| The number of metal titanium clips | |||

| 6.42 ± 0.64 | 6.76 ± 0.85 | 0.056 | |

| Postoperative hospital stays | |||

| Mean (d) | 6.56 ± 0.68 | 6.63 ± 0.77 | 0.736 |

| Residual apparatus after operation | |||

| 3 months | 12 | 16 | 0.947 |

| 6 months | 6 | 7 | 0.763 |

| 12 months | 2 | 2 | 0.874 |

| ≥ 3 cm, < 4 cm, n = 58 | ≥ 4 cm, < 5 cm, n = 27 | P value | |

| Perforation | 0 | 0 | |

| Abdominal pain | 5 | 9 | 0.011 |

| Low fever | 4 | 9 | 0.005 |

| Operation time | |||

| Mean (min) | 63.43 ± 16.12 | 82.96 ± 24.12 | 0.000 |

| Closure time, single-nylon rope purse-string suture | |||

| Mean (min) | 25.86 ± 6.25 | 28.59 ± 7.78 | 0.138 |

| Closure time, second nylon rope purse-string suture | |||

| Mean (min) | 5.95 ± 1.17 | 6.33 ± 1.64 | 0.470 |

| The number of metal titanium clips | |||

| 6.21 ± 0.41 | 7.48 ± 0.69 | 0.000 | |

| Postoperative hospital stays | |||

| Mean (d) | 6.47 ± 0.65 | 6.89 ± 0.83 | 0.019 |

| Residual apparatus after operation | |||

| 3 months | 12 | 16 | 0.297 |

| 6 months | 6 | 7 | 0.933 |

| 12 months | 2 | 2 | 0.766 |

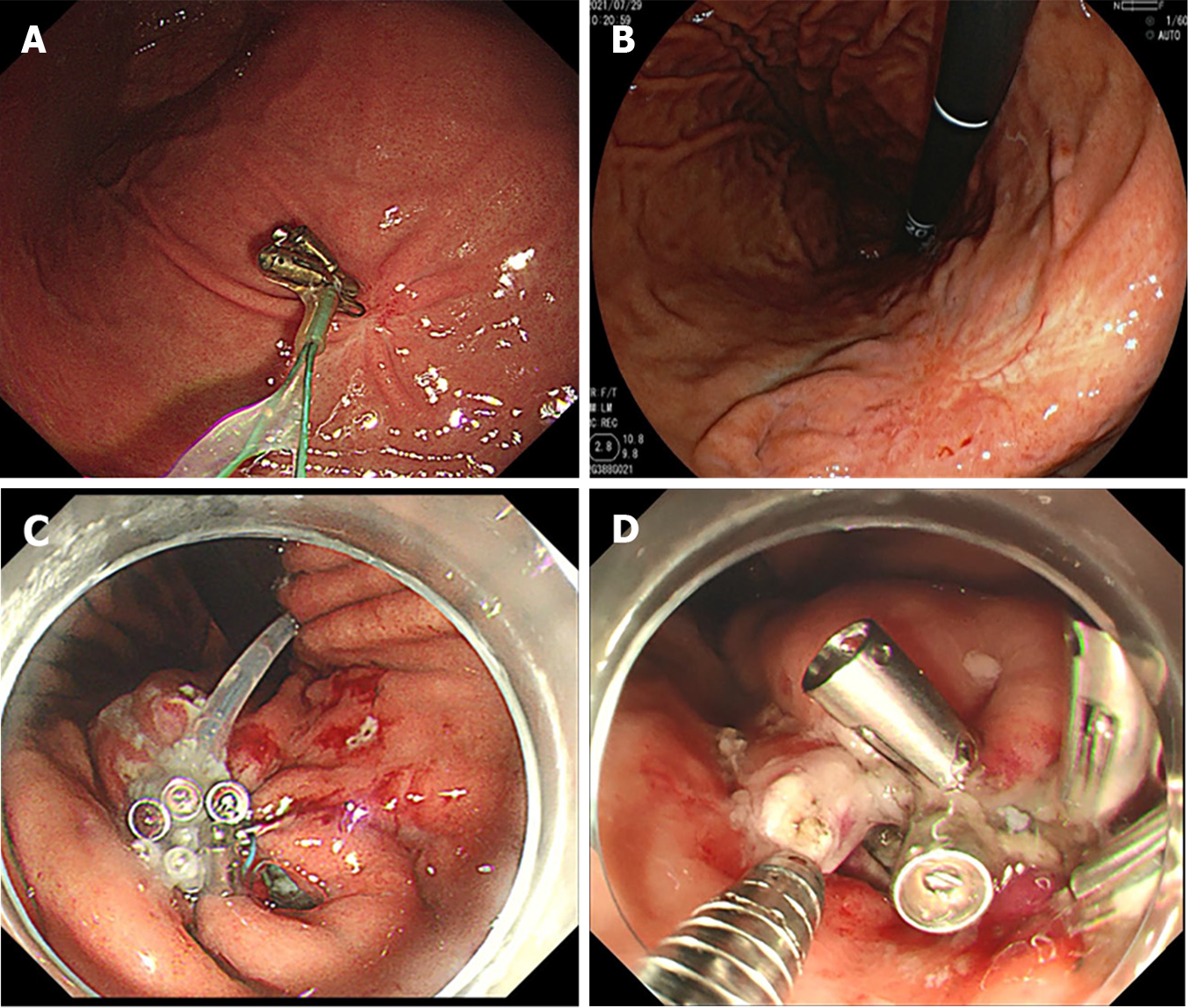

All patients underwent gastroscopic reexamination at 3, 6, and 12 months postoperatively to determine the healing status of the postoperative wound surface. Ultrasonic gastroscopy can be used to detect recurrent and residual lesions. All 85 patients underwent gastroscopy three months postoperatively, and all the perforations were closed; 28 patients (28/85, 32.94%) still had titanium clips and nylon rope residues on the wound (Figure 3). Six months postoperatively, 13 patients (13/85, 15.29%) continued to have titanium clips and nylon rope residues. Twelve months postoperatively, four patients (4/85, 4.71%) had titanium clips and nylon rope residues. All the wounds healed completely (Figure 3). No lesion residue or recurrence was observed on gastroscopy in any patient.

With advancements in endoscopic technology and the continuous update of endoscopic-assisted therapy instruments, most gastrointestinal SMTs can be completely resected[11]. However, in daily clinical practice, some patients with large (≥ 3 cm) upper gastrointestinal SMTs are unwilling to risk surgical complications and prefer endoscopic to surgical resection. In addition to ensuring R0 tumor resection, successful repair of wound defects after EFTR is pivotal for achieving favorable outcomes during endoscopic treatment[12]. Wound repair is a challenging aspect of endoscopic treatment for gastrointestinal SMTs and is an essential step in minimizing complications and eliminating the need for subsequent surgical interventions.

Endoscopic wound closure has become increasingly safe and effective. Wound closure has evolved from the use of pure titanium clips to joint suturing with titanium clips and nylon ropes, from double forceps endoscopy to single forceps endoscopy, and with the emergence of various new sealing instruments (such as OTSCs)[13,14]. This study introduces a simple and innovative approach for endoscopic closure that can be used to effectively and safely close gastric wall wounds. Double-nylon purse-string sutures can achieve more reliable and secure closure of large gastric wall defects than titanium clip closures. Secure closure is particularly beneficial for SMTs larger than 3 cm, as it enhances the stability of wound closure compared with single-nylon purse-string sutures. Additionally, this technique has economic advantages and is more conducive to widespread adoption than devices such as OTSCs.

All patients in this study had lesions in the stomach fundus or the lesser curvature of the gastric body. These patients were deliberately selected because these sites are common sites for gastric SMTs[15,16]. These sites are characterized by greater gastric wall tension and a more pliable mucosal muscularis layer. Among patients in this study, gaps on the wound surface were still observed after successfully completing a single-nylon rope purse-string suture (Figure 3). Adding a second nylon rope for fixation allowed complete closure of the wound surfaces. Therefore, for SMTs > 3 cm that have undergone EFTR, a double-nylon rope purse-string suture was safer and more effective than a single-nylon rope suture.

This study conducted further subgroup analyses. We found no significant differences between lesion repair at different locations in terms of the operative time, closure time, number of metal titanium clips used, postoperative hospital stay, complications, or residual apparatus after the operation. However, significant differences were found among lesions of different sizes in the operative time, number of metal titanium clips used, complications, and postoperative hospital stay. Larger lesions require resection over a larger area, resulting in an increased operative time and the use of additional metal titanium clips. An increased resection time is also associated with a greater likelihood of minor postoperative complications. However, no differences were observed in closure time or postoperative instrument residue, suggesting that even for large lesions, there was no increase in the technical difficulty of suturing, and optimal suture results were achieved.

One patient in our study experienced throat discomfort and hoarseness after surgery. We considered that the cricoarytenoid joint had been dislocated during tumor removal; however, the patient’s condition normalized after manual reduction. This patient was not included in the analysis because we did not believe this to be a problem during excision and suturing.

In the purse-string suture technique, endoscopists can easily clamp the mucosal edges of the gastric wall incision using titanium clips while securing the nylon ropes. However, when dealing with larger wounds, instrument-assisted closure can increase the tension on the gastric wall, which may exceed the strength of endoscopic-assisted instruments. To address this issue, a second nylon rope was used to reinforce and tighten the suture to gradually close the defect in the gastric wall. We were prompted to add a second nylon rope after observing that gaps still existed on the wound surface following a single-nylon rope purse-string suture to close large lesions following EFTR. When many titanium clips are required for fixation, the instrument can crack when the clips are tightened, and these gaps cannot be eliminated by tension from the nylon rope. Reducing the number of titanium clips results in larger mucosal gaps between clips and the formation of folds in the mucosa during tightening, which creates additional gaps. To prevent gaps, a second nylon rope can be used for secondary ligation either at the root of the titanium clip or at the base of the mucosa. This increases the pressure, helps gather mucosa around the wound, and effectively prevents the formation of gaps. We noted that the stomach body has more and deeper gastric wall folds, increasing the likelihood of postclosure gaps during the tightening of sutures. We advocate using a second nylon rope for secondary fixation to help avoid postclosure gaps and ensure more secure closure.

Furthermore, repeated electrocoagulation of the mucosa is necessary during EFTR to ensure a smooth and safe operation. To address this issue, using a secondary nylon rope for fixation helps reduce tension and ensures that the titanium clips are not easily displaced or lost. In cases where lesions are located in the lesser curvature of the gastric body, which has numerous folds and a poor visual field, there may be uncertainties in clamping the titanium clips. In such situations, complete sealing of the wound surface can be achieved through secondary fixation with a nylon rope. This further stabilizes the suture effect of the titanium clips and first nylon rope, preventing premature detachment of the suture material and reducing the risk of postoperative complications. Overall, using a secondary nylon rope for reinforcement and stabilization is beneficial for patients with mucus hyperemia and edema, as well as in situations with poor visualization and uncertain clamping of titanium clips. This helps ensure secure closure, prevents complications, and enhances the overall success of the procedure.

The success of purse-string suturing depends on the correct evaluation of the wound size[14] and selection of an appropriate titanium clip and nylon rope. Care was taken to maintain the nylon rope on the outside of all titanium clips when placing the second nylon rope over the wound after the initial purse sutures. This ensured that the second nylon rope was completely wrapped around the base when tightened, closing any gaps after the initial closure. Double-nylon rope purse-string sutures greatly broaden the indication range of traditional purse sutures and enable the treatment of more SMTs via minimally invasive endoscopic resection.

In this study, we focused on large lesions with a diameter of 3 cm or greater. The double-nylon rope purse-string suturing technique demonstrated a 100% success rate in achieving wound closure. No severe adverse events were observed during the postoperative period, and there were no cases of gastrointestinal leakage or sinus tract formation. All wounds healed completely, and scars were observed during the follow-up period.

Based on these results, the double-nylon rope purse-string suture method is safe and effective, particularly for lesions with a diameter of 3 cm or larger located in the fundus of the stomach or the lesser curvature of the gastric body. This was a retrospective, nonrandomized, single-center study with a small sample size, which has many limitations. Notably, this study did not explore the application of this closure technique for repairing wound defects in other parts of the stomach or digestive tract. To further validate and expand the application of this technique, it is necessary to increase operational experience and conduct additional clinical investigations. Continued research and clinical validation will contribute to a better understanding and broader implementation of this closing technique.

In summary, the double-nylon rope purse-string suture technique is a viable, effective, and safe method for closing gastric wall defects following EFTR for gastric SMTs. It offers several advantages over traditional and previously reported methods, including ease of operation, cost-effectiveness, and favorable prognostic outcomes. It is hoped that additional studies will be conducted to enhance the scientific understanding of this closure method and ultimately benefit a larger number of patients.

Endoscopic full-thickness resection (EFTR) is increasingly employed in patients with deep lesions, such as submucosal tumors (SMTs), due to its minimal invasiveness and preservation of stomach anatomy and function. EFTR is considered a last-resort endoscopic treatment, like surgical resection, as it allows for the removal of deeper lesions and enables more comprehensive histological assessment. However, during SMT treatment with EFTR, the lesion is completely removed through intentional perforation, necessitating the closure of the resulting wound. Effective closure of the gastric wall defect is crucial for patient safety and the successful implementation of EFTR. Inadequate closure may lead to a higher risk of delayed perforation, requiring subsequent surgical intervention. In recent years, a variety of closure techniques have been utilized to suture gastric wall defects following EFTR. These methods include wound clipping, endoscopic stapling, the endoscopic full-layer folding system, the over-the-scope-clip system, the OverstitchTM endoscopic suturing system, and bioabsorbable fillers. While some of these techniques are straightforward to execute, they may not achieve complete closure for larger perforations of the gastric wall. On the other hand, certain advanced endoscopic devices are relatively expensive and demand a higher level of expertise, limiting their widespread adoption in medical institutions.

To find a more economical, practical and convenient wound closure method for large wound after EFTR.

The double-nylon rope purse-string suture technique is a viable, effective, and safe method for closing gastric wall defects following EFTR for gastric SMTs. It offers several advantages over traditional and previously reported methods, including ease of operation, cost-effectiveness, and favorable prognostic outcomes. It is hoped that additional studies will be conducted to enhance the scientific understanding of this closure method and ultimately benefit a larger number of patients.

This study was a retrospective single-arm clinical trial. This study aimed to evaluate the clinical value of double-nylon purse-string sutures in closing gastric defects following submucosal tumor treatment with endoscopic full-thickness resection. We selected tumors larger than 3 cm, which had not been seen in previous studies. This new endoscopic closure method was proposed on the premise of rich clinical cases and operational experience in our center.

The double-nylon rope purse-string suture technique is a viable, effective, and safe method for closing gastric wall defects following EFTR for gastric SMTs.

The double-nylon rope purse-string suture method is safe and effective, particularly for lesions with a diameter of 3 cm or larger located in the fundus of the stomach or the lesser curvature of the gastric body.

From this study, we propose a new endoscopic closure method. In addition to the good practice results in the stomach, we will continue to validate the effectiveness and safety of this approach in other parts of the digestive tract. It is hoped that this study can be continued in multi-center in the future.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Lee SW, South Korea; Sertkaya M, Turkey S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Standards of Practice Committee; Faulx AL, Kothari S, Acosta RD, Agrawal D, Bruining DH, Chandrasekhara V, Eloubeidi MA, Fanelli RD, Gurudu SR, Khashab MA, Lightdale JR, Muthusamy VR, Shaukat A, Qumseya BJ, Wang A, Wani SB, Yang J, DeWitt JM. The role of endoscopy in subepithelial lesions of the GI tract. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:1117-1132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 119] [Cited by in RCA: 181] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Antonino G, Alberto M, Michele A, Dario L, Fabio T, Mario T. Efficacy and safety of gastric exposed endoscopic full-thickness resection without laparoscopic assistance: a systematic review. Endosc Int Open. 2020;8:E1173-E1182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang C, Gao Z, Shen K, Cao J, Shen Z, Jiang K, Wang S, Ye Y. Safety and efficiency of endoscopic resection versus laparoscopic resection in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2020;46:667-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huang LY, Cui J, Lin SJ, Zhang B, Wu CR. Endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastric submucosal tumors arising from the muscularis propria layer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:13981-13986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | ASGE Technology Committee; Aslanian HR, Sethi A, Bhutani MS, Goodman AJ, Krishnan K, Lichtenstein DR, Melson J, Navaneethan U, Pannala R, Parsi MA, Schulman AR, Sullivan SA, Thosani N, Trikudanathan G, Trindade AJ, Watson RR, Maple JT. ASGE guideline for endoscopic full-thickness resection and submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection. VideoGIE. 2019;4:343-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 147] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Rajan E, Wong Kee Song LM. Endoscopic Full Thickness Resection. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:1925-1937.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Gluzman MI, Kashchenko VA, Karachun AM, Orlova RV, Nakatis IA, Pelipas IV, Vasiukova EL, Rykov IV, Petrova VV, Nepomniashchaia SL, Klimov AS. Technical success and short-term results of surgical treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an experience of three centers. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xu MM, Angeles A, Kahaleh M. Endoscopic full-thickness resection of gastric stromal tumor: one and done. Endoscopy. 2018;50:E42-E43. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Modayil RJ, Zhang X, Khodorskiy D, Stavropoulos SN. Advanced resection and closure techniques for endoscopic full-thickness resection in the gastric fundus. VideoGIE. 2020;5:61-63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Wang S, Luo H, Shen L. Clinical Efficacy of Single-Channel Gastroscopy, Double-Channel Gastroscopy, and Double Gastroscopy for Submucosal Tumors in the Cardia and Gastric Fundus. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:1307-1313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhang Y, Peng JB, Mao XL, Zheng HH, Zhou SK, Zhu LH, Ye LP. Endoscopic resection of large (≥ 4 cm) upper gastrointestinal subepithelial tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer: a single-center study of 101 cases (with video). Surg Endosc. 2021;35:1442-1452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yamamoto Y, Uedo N, Abe N, Mori H, Ikeda H, Kanzaki H, Hirasawa K, Yoshida N, Goto O, Morita S, Zhou P. Current status and feasibility of endoscopic full-thickness resection in Japan: Results of a questionnaire survey. Dig Endosc. 2018;30 Suppl 1:2-6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ye LP, Yu Z, Mao XL, Zhu LH, Zhou XB. Endoscopic full-thickness resection with defect closure using clips and an endoloop for gastric subepithelial tumors arising from the muscularis propria. Surg Endosc. 2014;28:1978-1983. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shi D, Li R, Chen W, Zhang D, Zhang L, Guo R, Yao P, Wu X. Application of novel endoloops to close the defects resulted from endoscopic full-thickness resection with single-channel gastroscope: a multicenter study. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:837-842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Li QL, Yao LQ, Zhou PH, Xu MD, Chen SY, Zhong YS, Zhang YQ, Chen WF, Ma LL, Qin WZ. Submucosal tumors of the esophagogastric junction originating from the muscularis propria layer: a large study of endoscopic submucosal dissection (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:1153-1158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Wang YP, Xu H, Shen JX, Liu WM, Chu Y, Duan BS, Lian JJ, Zhang HB, Zhang L, Xu MD, Cao J. Predictors of difficult endoscopic resection of submucosal tumors originating from the muscularis propria layer at the esophagogastric junction. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2022;14:918-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |