Published online Feb 28, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i8.799

Peer-review started: December 7, 2023

First decision: December 21, 2023

Revised: January 2, 2024

Accepted: January 30, 2024

Article in press: January 30, 2024

Published online: February 28, 2024

Processing time: 80 Days and 17 Hours

Approximately 12-72 million people worldwide are co-infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis delta virus (HDV). This concurrent infection can lead to several severe outcomes with hepatic disease, such as cirrhosis, fulminant hepatitis, and hepatocellular carcinoma, being the most common. Over the past few decades, a correlation between viral hepatitis and autoimmune diseases has been reported. Furthermore, autoantibodies have been detected in the serum of patients co-infected with HBV/HDV, and autoimmune features have been reported. However, to date, very few cases of clinically significant autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) have been reported in patients with HDV infection, mainly in those who have received treatment with pegylated interferon. Interestingly, there are some patients with HBV infection and AIH in whom HDV infection is unearthed after receiving treatment with immunosuppressants. Consequently, several questions remain unanswered with the challenge to distinguish whether it is autoimmune or “autoimmune-like” hepatitis being the most crucial. Second, it remains uncertain whether autoimmunity is induced by HBV or delta virus. Finally, we investigated whether the cause of AIH lies in the previous treatment of HDV with pegylated interferon. These pressing issues should be elucidated to clarify whether new antiviral treatments for HDV, such as Bulevirtide or immu-nosuppressive drugs, are more appropriate for the management of patients with HDV and AIH.

Core Tip: There are some pressing issues that should be elucidated in order to clarify whether new antiviral treatments for hepatitis delta virus (HDV), such as Bulevirtide, or immunosuppressive drugs, are more appropriate for the management of patients with HDV and autoimmune hepatitis (AIH). Firstly, several questions remain unanswered with the challenge to distinguish whether it is autoimmune or “autoimmune-like” hepatitis being the most crucial. Secondly, it yet remains uncertain whether autoimmunity is induced by the hepatitis B virus or the Delta virus. Finally, if the cause of AIH lies on the previous treatment of HDV with pegylated interferon.

- Citation: Gigi E, Lagopoulos V, Liakos A. Management of autoimmune hepatitis induced by hepatitis delta virus. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(8): 799-805

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i8/799.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i8.799

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) was first recognized back in late 1970s as new antigen in the serum of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive patients, termed δ, whilst subsequent clinical trials in chimpanzees proved its existence in 1980[1]. HDV, the smallest pathogenic virus in human virology, consists of a circular single-stranded negative RNA genome and two types of hepatitis delta antigens, small and large (L-HDAg and S-HDAg, respectively), enveloped by HBsAg. Eight HDV genotypes with various geographical distributions were identified. With HBsAg on its surface, HDV enters hepatocytes via sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide (NTCP). Genomic HDVRNA then moves to the nucleus, where it replicates via a rolling-circle mechanism. During replication, two species of HDAg (L-HDAg and S-HDAg) are formed: S-HDAg triggers further replication of the virus, while L-HDAg inhibits replication and promotes virion packaging through farnesylation[2]. Many clinical studies have shown that HDV infection most often causes progressive liver disease more rapidly than other viral hepatitis, leading to liver cirrhosis in 70% of cases within 5 to 10 years[3]. Furthermore, HDV is independently associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) than hepatitis B virus (HBV) monoinfection[4] and has been associated with the development of autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), as in the serum of HBV/HDV co-infected patients, positive autoantibodies have been detected, and autoimmune features have been reported[5].

AIH is an immune-mediated inflammatory disease of the liver, characterized by circulating autoantibodies, increased concentrations of immunoglobulin G (IgG), and specific histological features[6]. The origin of the disease is presumed to be a loss of immunologic tolerance against hepatocytes induced by environmental factors, but also triggered by specific viral infections (Hepatitis B, C, E, A, and Epstein-Barr), genetic factors, exposure to certain drugs (e.g., nitrofurantoin, minocycline), and some individual risk factors (e.g., sex, age, hormonal status, and comorbidities)[7]. The clinical presentation can be extremely heterogeneous, ranging from asymptomatic disease to fulminant hepatitis, leading to acute liver failure, with the acute onset of AIH being the most frequent pattern worldwide[7]. AIH can be classified into two types according to the pattern of autoantibodies detected. AIH type 1 is characterized by the presence of antinuclear antibodies (ANA) and/or smooth muscle autoantibodies (SMA) and sometimes perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA). AIH type 2 is characterized by the presence of antibodies against kidney microsome-1 (anti-LKM1), anti-LKM 3, and/or liver cytosolic type 1[8].

AIH is diagnosed based on clinical, serological, and histological data. Clinical data may include nonspecific symptoms such as fatigue, arthralgia, malaise, amenorrhea, or symptoms and signs of hepatic cirrhosis. Laboratory findings included high concentrations of aminotransferases, detection of the specific autoantibodies mentioned above, and hypergammaglobulinemia (IgG). The histological features of AIH are not typical, as they are similar to those observed in active chronic hepatitis, mainly portal lymphoplasmacytic inflammation with interfacial activity and variable degrees of lobular hepatitis, emperipolesis, and hepatocyte rosettes[7,8]. Although imaging studies have a limited role in the diagnosis of AIH, they are useful for the assessment of liver complications, progression to cirrhosis, and screening for HCC. Currently, imaging is used worldwide to evaluate liver disease progression in patients with AIH. Ultrasound elastography is the most useful noninvasive tool for monitoring patients treated for AIH[9].

Once AIH is diagnosed, treatment is initiated. In most cases, untreated AIH may lead to liver failure and death within five years of onset, whereas properly treated patients have an excellent prognosis. The aim of treatment for AIH is to achieve and maintain disease remission and symptom resolution, thus halting or even reversing liver damage and fibrosis. However, treatment may cause serious side effects and significant impairment of quality of life. Therefore, an individualized approach is required, taking into consideration not only disease-related factors (inflammatory activity and stage of fibrosis), but also patient characteristics and values (such as life expectancy, comorbidities, living conditions, and patients’ personal preferences).

Steroids remain the cornerstone of AIH remission, which is defined as a full biochemical response (normalization of both transaminases and IgG concentrations). The recommended initial dosage varies depending mostly on the profile of the patient and/or the stage of AIH. Starting with a dose of 0.5 mg/kg/d seems to have comparable efficacy to the widely accepted initial dose of 1.0 mg/kg/d, with a slightly slower response rate but fewer side effects; thus, doses higher than 0.5 mg/kg/d of prednisolone should be reserved only for severe acute disease. The response to steroid therapy is usually rapid, as transaminase concentrations start falling within a week, while IgG levels subside more slowly due to their prolonged half-life. Steroid tapering should be started as soon as signs of a biochemical response are observed, usually in steps of 5 mg every week, down to 10 mg of prednisolone per day, until a complete biochemical response is achieved. Budesonide can be used as an alternative to prednisolone, showing a slightly slower response and fewer side effects[10,11].

Although steroids are regarded as first-line treatment, azathioprine is used for maintenance as a corticosteroid-sparing regimen. Azathioprine can induce sustained remission while reducing the side effects of steroid therapy. Therefore, azathioprine should be administered as early as possible following the initial response, usually 7 d to 14 d after steroid treatment. Azathioprine should also be started at a low dose to avoid intolerance; the recommended dose is 50 mg/d, with careful monitoring of side effects, including full blood counts taken every 1 wk to 2 wk. If no side effect is observed, the dose of azathioprine should then be increased to 1-2 mg/kg/d. Once a complete biochemical response is achieved, immunosuppressive therapy should be titrated to the level required to retain the full response, with steroids preferably tapered out completely. In case of relapse during tapering, steroids should be reintroduced at slightly higher dose[12,13]. For patients who cannot tolerate azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can be used as an alternative agent at the usual dose of 2 g/d[14]. Finally, if the response to MMF is inadequate, multiple salvage therapies have been described, including cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and other immunomodulatory agents (methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, rituximab, and infliximab). Nevertheless, none of the aforementioned agents have been assessed in controlled clinical trials. Therefore, evidence for third-line treatment options remains scarce, and these patients should be preferably managed in large-volume centers with sufficient expertise in AIH[6].

The treatment duration of for AIH is controversial. Considering that AIH is an idiopathic disease that develops in a background of genetic susceptibility, most patients require long-term, most likely lifelong, therapy. Only 10%-20% of patients with AIH can safely discontinue immunosuppressive therapy and maintain remission. Withdrawal of immunosuppressive agents can be attempted when a complete biochemical response has been achieved for more than two years on monotherapy, with alanine transaminase concentrations in the lower range of normal values and IgG concentrations below 12 g/L. As there is a high chance of relapse, patients with complete treatment withdrawal should be closely monitored, especially in the first six months. Late relapses can also occur decades after sustained remission, highlighting the need for lifelong surveillance in virtually all patients[13].

However, there are certain patients for whom immunosuppressive treatment is contraindicated, including cases of AIH with an acute onset and rapid progression to fulminant liver disease or patients who already have end-stage liver disease at the time of diagnosis. In both cases, liver transplantation was the only treatment option[7].

The association of HDV with positive autoantibodies and autoimmune features has been suspected for years, although it was initially suggested that hepatitis delta is directly cytopathic and that liver injury is not immunologically mediated[15]. It remains debatable whether the autoimmune features derive from previous treatment with pegylated interferon or whether HDV induces autoimmunity through molecular mimicry and bystander activation. Considerable research has been conducted on the role of HBV in inducing autoimmunity[16]. Most antibodies used for viral hepatitis are non-disease-specific or non-organ-specific (NOSA). These antibodies include ANA, anti-SMA, anti-LKM1, anti-mitochondrial antibodies, and anti-soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas antibodies. In a recent study, Hermanussen et al[16] identified and analyzed three different cohorts: Forty-six patients with AIH, 42 patients with HDV, and 70 patients with HBV. They found that positive NOSA titers were more frequent in AIH than in HDV (96% vs 69%) but more frequent in HDV than in HBV (69% vs 43%). With respect to individual antibodies, ANA titers were more frequent in patients with AIH than in those with HDV (89% vs 76%). In addition, higher titers ≥ 1:320 were noted in 63% of patients with AIH compared with 28% in the HDV cohort. Compared to patients with HBV, ANA titers were more commonly elevated in patients with HDV co-infection (HDV 67% vs HBV 43%). No difference was noted in ANA titers between patients with and without detectable HDV-RNA. The same trend was observed for SMA titers, which were more frequently encountered in AIH patients than in HDV and HBV patients (AIH 50% vs HDV 16% vs HBV 3%). Patients with detectable HDV-RNA RNAtested positive more frequently, and the titers were higher than those in patients with undetectable HDVRNA. Finally, IgG levels increased in 73%, 54% of patients with HDV and 12% of patients with AIH, HDV, and HBV[16]. In addition to this study, previous reports have shown a positive correlation between pegylated interferon treatment in HBV patients and the induction of AIH in approximately 25%-40%[17]. Furthermore, isolated cases of patients with hepatitis delta have shown that AIH is also observed after treatment with pegylated interferon[18]. In contrast, a case of HDV-RNA flare has been reported in a previously negative patient who received immunosuppressive treatment for AIH[5].

Until recently, the management of chronic hepatitis delta (CHD) was encompassed within the HBV guidelines, as CHD was recognized as an HBV-dependent rare disease. It has even been designated an orphan disease because it affects only a small fraction of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive patients. Advancements in the knowledge of HDV pathogenesis and the HDV life cycle have led to the identification of new therapeutic targets. For the first time since the discovery of HDV in the 70’s, HDV-specific antiviral agents have undergone Phase III clinical trials. Bulevirtide (BLV) was the first HDV-specific antiviral agent to receive marketing authorization from the EMA in July 2020. Owing to the complexity of CHD clinical management on the one hand and the newly available knowledge and therapeutic perspectives, the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) commissioned the first international clinical practice guideline (CPG)[19] on the management of HDV-infected patients, which was first announced during the EASL meeting in June 2023.

According to the EASL CPG2023, pegylated interferon (PegIFNα) remains a therapeutic option and is recommended for all patients with CHD and compensated liver disease, irrespective of the presence of cirrhosis, for 48 wk (LoE 2, strong recommendation, consensus)[19]. PegIFNα is associated with a decline in both HBV and HDV markers, and recent studies have shown that it significantly reduces HDV-RNA when administered in the early stages of infection[20], suggesting an inhibitory effect on viral entry and suppression of cell division-mediated HDV spread[21]. In contrast, a recent meta-analysis of 13 studies reported a virological response at 24 wk post-treatment in only 29% of patients receiving PegIFNα, and that 50% of these patients developed virological relapse later, up to 10 years after the end of treatment[22,23].

BLV is a synthetic myristoylated lipopeptide consisting of 47 amino acids in the preS1 domain of the HBV large surface protein that blocks the attachment of HBsAg to the cell entry receptor, NTCP[24]. It has recently been recommended for all patients with CHD and compensated liver disease (LoE 3, strong recommendation and consensus). The optimal dose and duration have not yet been established thus, until further data becomes available, long-term treatment with 2 mg BLV once daily may be considered safe and adequate (LoE 5, weak recommendation, consensus[19]. Real-world evidence from more than 500 patients treated in France, Germany, Austria, and Italy was presented at international meetings. In the French Early Access Cohort study, an increased rate of virological response from month 12 (33%) to month 24 (68%) was observed after BLV[25]. In the German real-world experience study including 114 patients BLV showed high rates of virological response (≥ 2 Log HDV-RNA decline) in 74% of patients, in a mean intervention period of 38.0 wk ± 17.6 wk. Interestingly, BLV was well tolerated without major adverse effects even in five patients with decompensated cirrhosis at baseline who achieved virological and biochemical responses[26].

The rationale for combination therapy with BLV and PegIFNα relies on the fact that PegIFNα exhibits immunomodulatory and antiviral properties and is able to inhibit cell division-mediated HDV spread, whereas BLV inhibits HDV from entering hepatocytes, thus preventing further infection. This combination is also recommended by EASL CPG 2023 for patients without PegIFNα intolerance or contraindications (LoE 5, weak recommendation, consensus)[19], In the MYR203 study, the patients were treated for 48 wk with combination therapy. Twenty-four weeks after the end of treatment, HDVRNA was undetectable in 53% of the patients who received BLV 2 mg/d. The rates of sustained virological response were 27% and 7% in patients treated with 5 and 10 mg daily respectively[27]. In the ongoing MYR204 study, patients were randomized to receive combination treatment with BLV at a dose of 2 or 10 mg/d for 48 wk and then continued with BLV monotherapy for another 48 wk, or monotherapy with BLV at a dose of 10 mg for 96 wk. In the 24th wk of treatment, patients receiving combination therapy achieved a greater decline in HDV-RNA levels than those treated with bulevirtidine monotherapy (92% when administered PegIFNα + 10 mg BLV vs 88% PegIFNα + 2 mg BLV vs 72% in BLV 10 mg monotherapy). Although these data are promising, the number of patients was small and some points need to be clarified further[28].

Better understanding of the HDV life cycle and its interplay with hepatocytes has enabled the development of new antiviral agents as possible candidates for CHD treatment. Besides BLV, an NTCP inhibitor, other promising agents include prenylation inhibitors that inhibit the prenylation of large HDV antigens, which are essential for HDV virion morphogenesis[29], and nucleic acid polymers, which interact with the hydrophobic surface of HBsAg and destabilize its assembly and secretion of subviral particles, leading to the degradation of intracellular HBsAg[30].

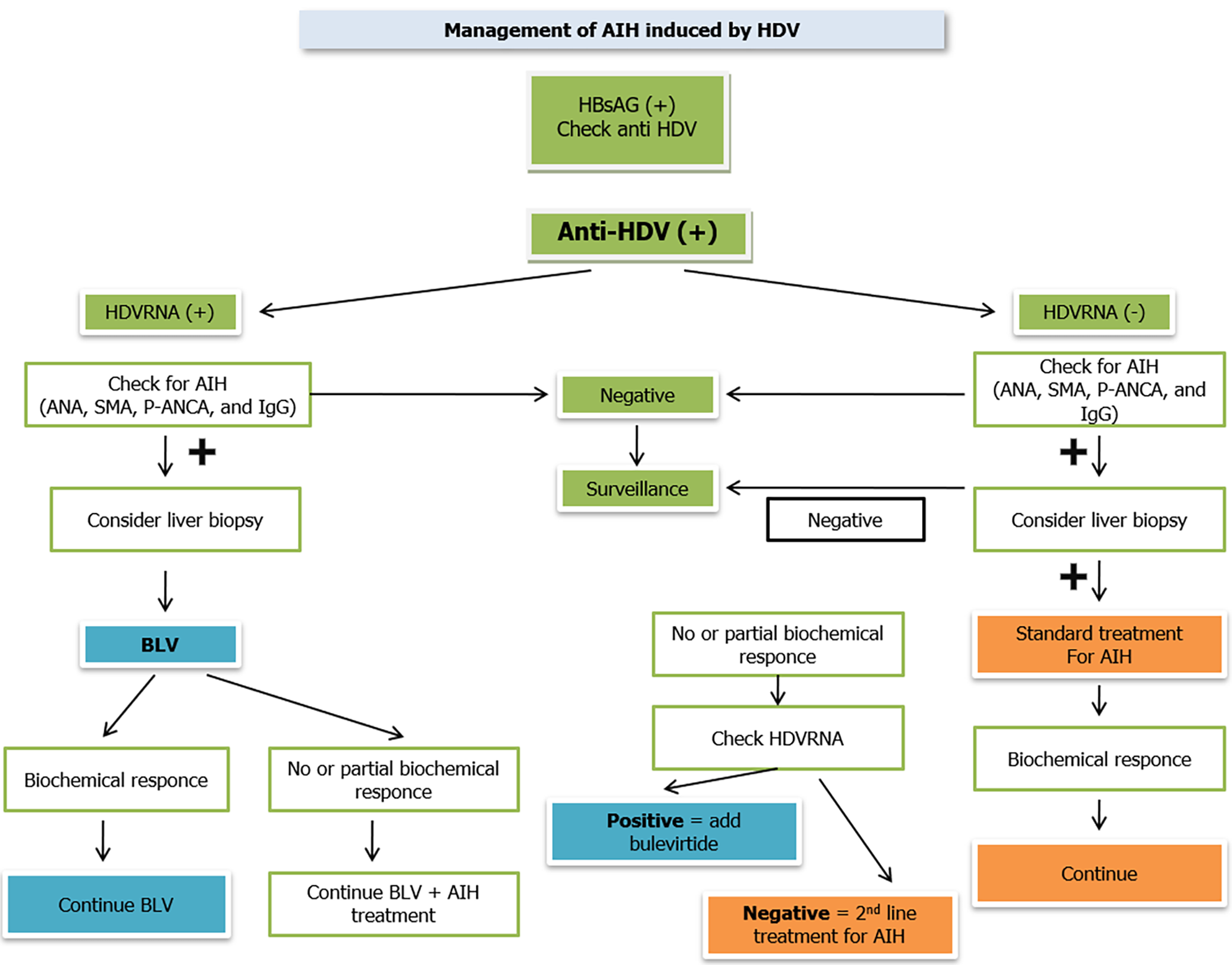

Over the last few decades, the interaction between viral hepatitis and autoimmune diseases has received increasing attention, with special interest in hepatitis B and D virus co-infection. In some CHD cases, clinical AIH has been reported after treatment with pegylated interferon. Starting from this observation, several questions arise, mainly concerning the exact correlation between the onset of autoimmune disease and hepatitis band D and treatment with pegylated interferon. Since all possible scenarios have been described, and many different cases have been reported in the literature, some steps have been proposed to manage AIH in patients with chronic hepatitis delta. First, all the HBsAg-positive patients were screened for HDV antibodies (anti-HDV). Consequently, HDV-RNA should be tested in all anti-HDV-positive patients, and regardless of the results, all anti-HDV-positive patients should be screened for AIH by testing serological data, suchas ANA, SMA, p-ANCA, and IgG levels, as well as transaminase levels. If serological data indicate AIH, a liver biopsy should be performed. Nevertheless, in anti-HDV-positive patients with detectable HDV-RNA levels and laboratory tests compatible with AIH, treatment with BLV should be initiated as PegIFNα is contraindicated in these cases. If a biochemical response is achieved with transaminase normalization and decreased IgG levels, treatment with BLV should still be continued. If there is a partial or no biochemical response, first-line AIH treatment with prednisolone 0.5 mg/kg of body weight/day should be considered together with BLV. First-line treatment for AIH should be applied in anti-HDV-positive patients with undetectable HDV-RNA levels, positive serological data for AIH, and elevated transaminase levels. If a biochemical response is achieved, prednisolone should be continued in a tapered manner as described previously. If there is a partial or no biochemical response, HDV-RNA should be checked, and if detectable, BLV should be initiated immediately. If it remains undetectable, second-line AIH treatment, that is, MMF, should be considered, but with great caution due to side effects. Despite a satisfactory biochemical response, all anti-HDV patients with undetectable HDVRNA who are being treated for AIH should be closely monitored for HDV reactivation by examining HDVRNA levels at least every 12-24 wk. Moreover, all patients undergoing AIH therapy should receive treatment with nucleos(t)ide analogs to avoid reactivation or exacerbation of chronic hepatitis B (Figure 1).

However, not all patients with CHD and AIH achieve biochemical and/or virological responses when treated with BLV and/or first- or second-line AIH therapy, particularly in patients with decompensated cirrhosis. In these patients, liver transplantation should be considered until new HDV anti-viral agents are available.

Therefore, patients with Chronic Hepatitis Delta should be evaluated for AIH. Once AIH is diagnosed, treatment with BLV should be initially administered and continued as long as there is a biochemical response. In patients with partial or no biochemical response, autoimmune therapy with prednisolone should be considered.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Greece

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Wang K, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Rizzetto M. Hepatitis D (DELTA). New Microbiol. 2022;45:149-154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Taylor JM. Infection by Hepatitis Delta Virus. Viruses. 2020;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fattovich G, Giustina G, Christensen E, Pantalena M, Zagni I, Realdi G, Schalm SW. Influence of hepatitis delta virus infection on morbidity and mortality in compensated cirrhosis type B. The European Concerted Action on Viral Hepatitis (Eurohep). Gut. 2000;46:420-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 312] [Cited by in RCA: 362] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Alfaiate D, Clément S, Gomes D, Goossens N, Negro F. Chronic hepatitis D and hepatocellular carcinoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Hepatol. 2020;73:533-539. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 25.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cardoso MF, Carvalho R, Correia FP, Branco JC, Nuno Costa M, Martins A. Autoimmune hepatitis induced by hepatitis delta virus: A conundrum. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2023;1-6. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2015;63:971-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 659] [Cited by in RCA: 848] [Article Influence: 84.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Muratori L, Lohse AW, Lenzi M. Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis. BMJ. 2023;380:e070201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 44.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang X, Jain D. The many faces and pathologic diagnostic challenges of autoimmune hepatitis. Hum Pathol. 2023;132:114-125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Barr RG. Shear wave liver elastography. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:800-807. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Pape S, Gevers TJG, Belias M, Mustafajev IF, Vrolijk JM, van Hoek B, Bouma G, van Nieuwkerk CMJ, Hartl J, Schramm C, Lohse AW, Taubert R, Jaeckel E, Manns MP, Papp M, Stickel F, Heneghan MA, Drenth JPH. Predniso(lo)ne Dosage and Chance of Remission in Patients With Autoimmune Hepatitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:2068-2075.e2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Manns MP, Woynarowski M, Kreisel W, Lurie Y, Rust C, Zuckerman E, Bahr MJ, Günther R, Hultcrantz RW, Spengler U, Lohse AW, Szalay F, Färkkilä M, Pröls M, Strassburg CP; European AIH-BUC-Study Group. Budesonide induces remission more effectively than prednisone in a controlled trial of patients with autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1198-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 349] [Cited by in RCA: 267] [Article Influence: 17.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Johnson PJ, McFarlane IG, Williams R. Azathioprine for long-term maintenance of remission in autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:958-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 269] [Cited by in RCA: 243] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kanzler S, Gerken G, Löhr H, Galle PR, Meyer zum Büschenfelde KH, Lohse AW. Duration of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune hepatitis. J Hepatol. 2001;34:354-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Hennes EM, Oo YH, Schramm C, Denzer U, Buggisch P, Wiegard C, Kanzler S, Schuchmann M, Boecher W, Galle PR, Adams DH, Lohse AW. Mycophenolate mofetil as second line therapy in autoimmune hepatitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:3063-3070. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Zauli D, Crespi C, Bianchi FB, Craxi A, Pisi E. Autoimmunity in chronic liver disease caused by hepatitis delta virus. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39:897-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Hermanussen L, Lampalzer S, Bockmann JH, Ziegler AE, Piecha F, Dandri M, Pischke S, Haag F, Lohse AW, Lütgehetmann M, Weiler-Normann C, Zur Wiesch JS. Non-organ-specific autoantibodies with unspecific patterns are a frequent para-infectious feature of chronic hepatitis D. Front Med (Lausanne). 2023;10:1169096. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Rathi C, Pipaliya N, Choksi D, Parikh P, Ingle M, Sawant P. Autoimmune Hepatitis Triggered by Treatment With Pegylated Interferon α-2a and Ribavirin for Chronic Hepatitis C. ACG Case Rep J. 2015;2:247-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Enc F, Ulasoglu C. A case of autoimmune hepatitis following pegylated interferon treatment of chronic hepatitis delta. North Clin Istanb. 2020;7:407-410. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on hepatitis delta virus. J Hepatol. 2023;79:433-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 137] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 63.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zhang Z, Filzmayer C, Ni Y, Sültmann H, Mutz P, Hiet MS, Vondran FWR, Bartenschlager R, Urban S. Hepatitis D virus replication is sensed by MDA5 and induces IFN-β/λ responses in hepatocytes. J Hepatol. 2018;69:25-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 109] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Zhang Z, Ni Y, Lempp FA, Walter L, Mutz P, Bartenschlager R, Urban S. Hepatitis D virus-induced interferon response and administered interferons control cell division-mediated virus spread. J Hepatol. 2022;77:957-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Wranke A, Hardtke S, Heidrich B, Dalekos G, Yalçin K, Tabak F, Gürel S, Çakaloğlu Y, Akarca US, Lammert F, Häussinger D, Müller T, Wöbse M, Manns MP, Idilman R, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Yurdaydin C. Ten-year follow-up of a randomized controlled clinical trial in chronic hepatitis delta. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:1359-1368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Heidrich B, Yurdaydın C, Kabaçam G, Ratsch BA, Zachou K, Bremer B, Dalekos GN, Erhardt A, Tabak F, Yalcin K, Gürel S, Zeuzem S, Cornberg M, Bock CT, Manns MP, Wedemeyer H; HIDIT-1 Study Group. Late HDV RNA relapse after peginterferon alpha-based therapy of chronic hepatitis delta. Hepatology. 2014;60:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 234] [Cited by in RCA: 221] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Yan H, Zhong G, Xu G, He W, Jing Z, Gao Z, Huang Y, Qi Y, Peng B, Wang H, Fu L, Song M, Chen P, Gao W, Ren B, Sun Y, Cai T, Feng X, Sui J, Li W. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. Elife. 2012;1:e00049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1280] [Cited by in RCA: 1600] [Article Influence: 123.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Ledinghen V, Hermabessiere P, Metivier S, Bardou-Jacquet E, Hilleret MN, Loustaud-Ratti V. Bulevirtide, with or without peg-interferon, in HDV infected patients in a real-life setting. Two-year results from the French multicenter early access program. 2022. [cited 12 January 2024]. Available from: https://www.natap.org/2022/AASLD/AASLD_47.htm. |

| 26. | Dietz-Fricke C, Tacke F, Zöllner C, Demir M, Schmidt HH, Schramm C, Willuweit K, Lange CM, Weber S, Denk G, Berg CP, Grottenthaler JM, Merle U, Olkus A, Zeuzem S, Sprinzl K, Berg T, van Bömmel F, Wiegand J, Herta T, Seufferlein T, Zizer E, Dikopoulos N, Thimme R, Neumann-Haefelin C, Galle PR, Sprinzl M, Lohse AW, Schulze Zur Wiesch J, Kempski J, Geier A, Reiter FP, Schlevogt B, Gödiker J, Hofmann WP, Buggisch P, Kahlhöfer J, Port K, Maasoumy B, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Deterding K. Treating hepatitis D with bulevirtide - Real-world experience from 114 patients. JHEP Rep. 2023;5:100686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Edemeyer H, Schöneweis K, Bogomolov PO, Voronkova N, ChulanovV, Stepanova T, Bremer B, Allweiss L, Dandri M, Burhenne J, Haefeli W, Ciesek S, Dittmer U, Alexandrov A, Urban S. Final results of a multicenter, open-label phase 2 clinical trial (MYR203) to assess safety and efficacy of myrcludex B in cwith PEG-interferon Alpha 2a in patients with chronic HBV/HDV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2019;70:e81. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Wedemeyer H, Schöneweis K, Bogomolov P, Blank A, Voronkova N, Stepanova T, Sagalova O, Chulanov V, Osipenko M, Morozov V, Geyvandova N, Sleptsova S, Bakulin IG, Khaertynova I, Rusanova M, Pathil A, Merle U, Bremer B, Allweiss L, Lempp FA, Port K, Haag M, Schwab M, Zur Wiesch JS, Cornberg M, Haefeli WE, Dandri M, Alexandrov A, Urban S. Safety and efficacy of bulevirtide in combination with tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in patients with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis D virus coinfection (MYR202): a multicentre, randomised, parallel-group, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2023;23:117-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Glenn JS, Watson JA, Havel CM, White JM. Identification of a prenylation site in delta virus large antigen. Science. 1992;256:1331-1333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 231] [Cited by in RCA: 248] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Boulon R, Blanchet M, Lemasson M, Vaillant A, Labonté P. Characterization of the antiviral effects of REP 2139 on the HBV lifecycle in vitro. Antiviral Res. 2020;183:104853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 9.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |