Published online Feb 21, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i7.673

Peer-review started: December 11, 2023

First decision: December 19, 2023

Revised: December 25, 2023

Accepted: January 22, 2024

Article in press: January 22, 2024

Published online: February 21, 2024

Processing time: 71 Days and 22.4 Hours

Gastric cystica profunda (GCP) represents a rare condition characterized by cystic dilation of gastric glands within the mucosal and/or submucosal layers. GCP is often linked to, or may progress into, early gastric cancer (EGC).

To provide a comprehensive evaluation of the endoscopic features of GCP while assessing the efficacy of endoscopic treatment, thereby offering guidance for diagnosis and treatment.

This retrospective study involved 104 patients with GCP who underwent endos

Among the 104 patients diagnosed with GCP who underwent endoscopic rese

The findings suggested that endoscopic resection might serve as an effective and minimally invasive treatment for GCP with or without EGC.

Core Tip: Gastric cystica profunda (GCP) associated early gastric cancer (EGC) was found to be relatively common. Irregular morphology and mucosal lesion type might be the risk factors for development of EGC in GCP. Endoscopic resection can be recommended as an effective and minimally invasive treatment for GCP with or without EGC.

- Citation: Geng ZH, Zhu Y, Fu PY, Qu YF, Chen WF, Yang X, Zhou PH, Li QL. Endoscopic features and treatments of gastric cystica profunda. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(7): 673-684

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i7/673.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i7.673

Gastric cystica profunda (GCP) represents a rare gastric lesion characterized by hyperplasia of connective tissues within the interstitium of the glands, involving the submucosal layer and occasionally extending to the muscularis propria of the stomach[1]. Initially, GCP was believed to be an inflammatory pseudotumor associated with ischemia, chronic inflammation, and mucosal defects that may arise from surgical procedures, biopsies, or polypectomies[2]. Widespread chronic active or atrophic gastritis is considered a significant contributing factor to the development of GCP[3]. Over recent years, the emergence of advanced endoscopic techniques such as endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and endoscopic resection has led to a gradual increase in the detection of non-surgically resected GCP cases.

Patients with GCP may either remain asymptomatic or present with non-specific digestive symptoms, including abdominal pain and belching[4]. Owing to the unremarkable clinical characteristics and nonspecific endoscopic manifestations, most clinicians possess limited understanding of GCP. Furthermore, GCP has been regarded as a potential premalignant lesion[5]; hence, the endoscopic diagnosis and early excision of GCP are deemed crucial[6,7]. In this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 104 cases of GCP treated by endoscopic resection at our center from October 2011 to December 2022. Our analysis was based on their clinical manifestations, endoscopic findings, pathological results, and treatments. The primary objectives were to delineate the endoscopic features of GCP associated with early gastric cancer (EGC) and to assess the impact of endoscopic resection on the diagnosis and treatment of GCP with EGC.

We conducted a single-center retrospective study involving 104 consecutive patients diagnosed with GCP who underwent endoscopic resection at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University (Shanghai, China) between October 2011 and December 2022. Only patients with complete demographic and clinical information, along with available follow-up data, were included in the study. Patients were assessed based on findings from endoscopy, computed tomography (CT) scans, or EUS during the preoperative phase. All patients with suspected GCP following endoscopic examination underwent biopsy for pathological confirmation. Lesion characteristics, endoscopic methods, complications, en-bloc resection rate, complete resection rate, and the occurrence of local recurrence were evaluated for all patients. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongshan Hospital in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (B2021-029), and written consent was obtained from all participating patients.

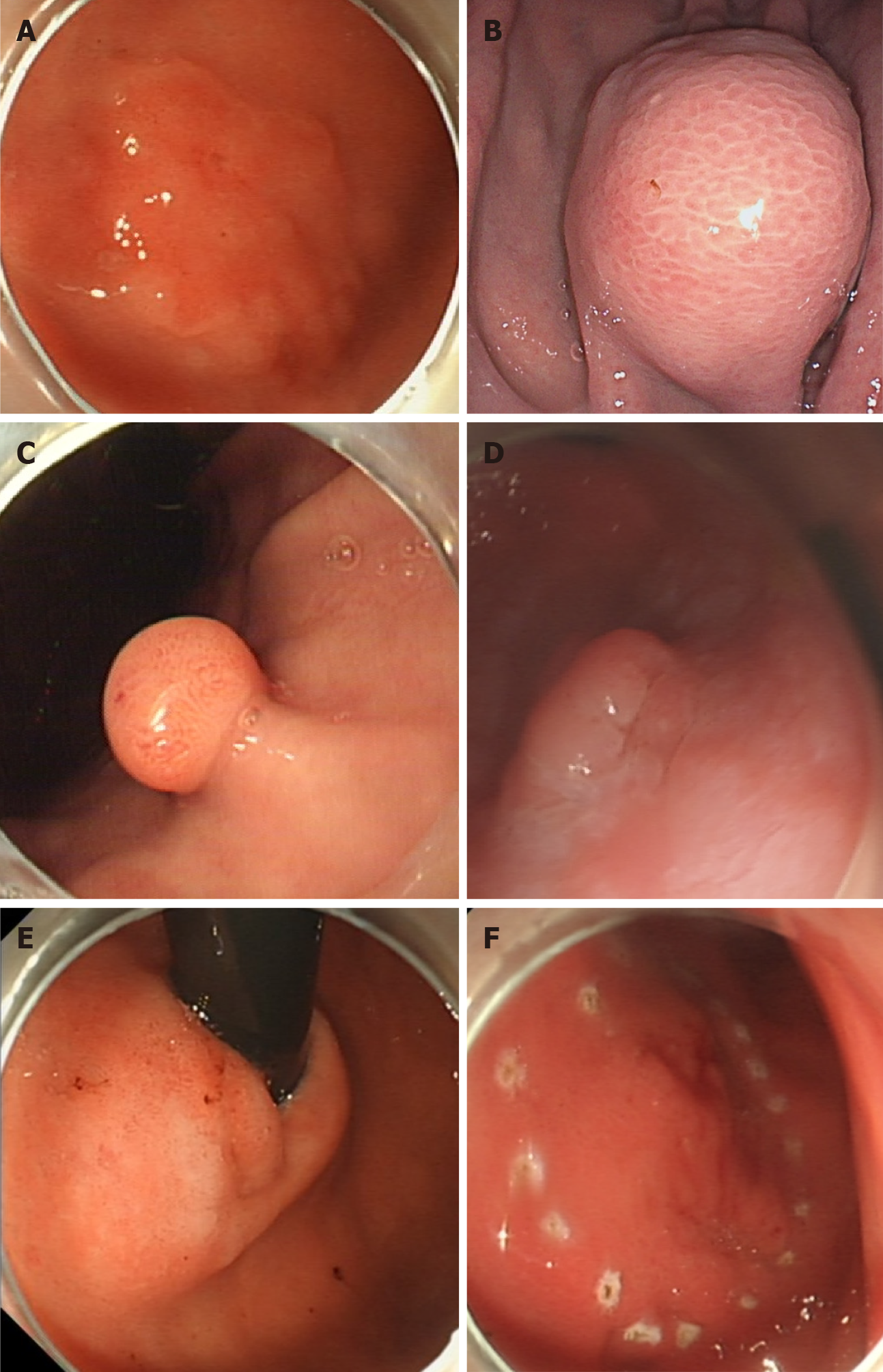

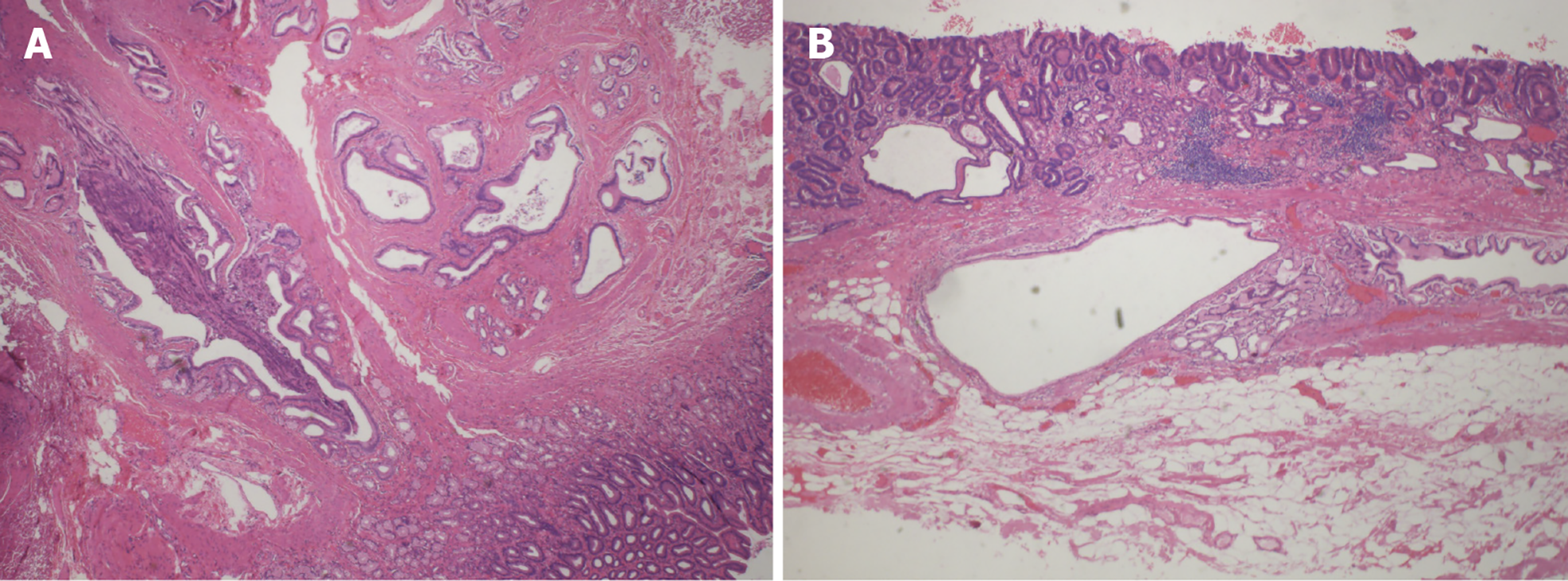

In this study, lesions were categorized into four types: Mucosal lesion type, polypoid type, submucosal lesion type, and thickened mucosa with rough wrinkles type (Figure 1A-D). According to the pathological diagnostic criteria for GCP, the presence of cystic structure expansion within the mucosal muscle layer and submucosal layer could confirm the diagnosis[8]. Building upon this criterion, the presence of cancerous changes in the gastric mucosal glands, with the lesion tissue confined to the mucosal and submucosal layers, led to a diagnosis of GCP with EGC (Figure 2). Each case was independently reevaluated by two experienced pathologists in a blinded manner, without access to clinical or endoscopic information.

Moreover, irregular shapes of GCP primarily encompassed three types: Mucosal lesion type, polypoid type, and submucosal lesion type. The irregular mucosal lesion type manifested as uneven surfaces with raised and depressed areas, often accompanied by surface erosion or ulcers. Irregular polypoid type GCP referred to type Ⅲ and Ⅳ polyps in the Yamada classification[9]. As for the irregularity of the submucosal lesion type, it mainly denoted an irregular shape, presenting as lobulated or branching[10].

The choice of endoscopic resection for GCP depended on the appearance during endoscopy. If it appeared as a mucosal lesion, submucosal tumor, or thickened and folded mucosa, then endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) would be employed. During ESD, operators cut the mucosa, dissected the submucosal layer, and subsequently removed the tumor after locating the lesions. If it appeared to be polyp-like and raised, then endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) or electric cutting would be performed.

Following endoscopic resection, a nasogastric tube was inserted to both decompress and monitor potential delayed bleeding from the wound. Additionally, we monitored postoperative symptoms. In cases where patients experienced persistent fever, hematemesis, melena, or pain, emergency endoscopy and CT scans were conducted. Moreover, proton pump inhibitors, antibiotics, and hemocoagulase injections were administered.

Endoscopic outcome assessments included: (1) The duration of procedure and hospital stay; (2) en-bloc resection (the excision of the tumor was performed in one piece without fragmentation) and complete resection (based on en-bloc resection, the excision was performed in a manner that ensures the absence of discernible residual tumors upon macroscopic evaluation at the resection site, coupled with negative margins upon pathologic examination); and (3) complications and local recurrence.

Patients underwent regular follow-up for the assessment of wound healing and the detection of local recurrence through endoscopy at 6 months post-resection. In cases where patients experienced relapses, EUS and CT scans were conducted to check for recurrent lesions.

Continuous variables were presented as means and SD, while categorical variables were displayed as numbers and percentages. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 26.0 and R 4.0.2.

A total of 104 consecutive patients, including 27 women and 77 men, with a mean age of 63.4 ± 11.0 years, were diagnosed with GCP and underwent endoscopic resection at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University in Shanghai, China. Among these patients, 12.5% had a history of prior gastric endoscopic or surgical treatment. The majority of patients were asymptomatic (n = 66, 63.5%), while 28 (26.9%) reported experiencing epigastric discomfort. Additionally, other symptoms such as regurgitation and melena were also observed (Table 1).

| | GCP (n = 104) |

| Demographic information | |

| Male | 77 (74.0) |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 63.4 ± 11.0 |

| History of gastric endoscopic or surgical treatment | 13 (12.5) |

| Symptom | |

| Asymptomatic | 66 (63.5) |

| Epigastric discomfort | 28 (26.9) |

| Regurgitation | 8 (7.7) |

| Melena | 2 (1.9) |

| Lesion characteristics | |

| Growth pattern | |

| Intraluminal growth | 103 (99.0) |

| Extraluminal growth | 1 (1.0) |

| Morphology | |

| Regular | 77 (74.0) |

| Irregular | 27 (26.0) |

| Mucosa | |

| Smooth | 40 (38.5) |

| Ulcerative | 64 (61.5) |

| Max diameter (mm), mean ± SD | 20.9 ± 15.3 |

| Location | |

| Cardia | 40 (38.5) |

| Gastric fundus | 8 (7.7) |

| Gastric body | 35 (33.7) |

| Gastric antrum | 21 (20.2) |

| Endoscopic features | |

| Mucosal lesion type | 62 (59.6) |

| IIa | 29 (46.8) |

| IIa + IIc | 4 (6.5) |

| IIc | 29 (46.8) |

| Polypoid type | 23 (22.1) |

| Submucosal lesion type | 17 (16.3) |

| Thickened mucosa with rough wrinkles type | 2 (1.9) |

| Infiltration depth | |

| Mucosa | 63 (60.6) |

| Submucosa | 40 (38.5) |

| Muscularis propria | 1 (1.0) |

| GCP with EGC | 62 (59.6) |

| Procedural outcomes | |

| Endoscopic methods | |

| Electric cutting | 7 (6.7) |

| EMR | 11 (10.6) |

| ESD | 80 (76.9) |

| ESE | 6 (5.8) |

| En-bloc resection | 95 (91.3) |

| Complete resection | 95 (91.3) |

| Suture method | |

| Unstitched | 62 (59.6) |

| Metal clip | 40 (38.5) |

| Nylon rope | 1 (1.0) |

| Metal clip and nylon rope | 1 (1.0) |

| Surgery time (min), mean ± SD | 73.9 ± 57.5 |

| Complications | 1 (1.0) |

| Hospital stay (d), mean ± SD | 3.4 ± 2.3 |

| Additional surgery | 1 (1.0) |

| Recurrence | 5 (4.8) |

The most commonly involved sites were the cardia (n = 40, 38.5%), followed by the gastric body (n = 35, 33.7%), gastric antrum (n = 21, 20.2%), and gastric fundus (n = 8, 7.7%). Furthermore, 13 patients (12.5%) with GCP had a history of gastric endoscopic or surgical treatment. Among them, three patients had a history of gastrectomy, where GCP occurred specifically at the cardia, particularly at the anastomotic site. Additionally, ten patients with GCP had undergone previous gastric endoscopic procedures, and seven of these GCP cases (70%) were located at the sites of prior gastric endoscopic interventions.

It was observed that 99% of GCP cases manifested an intraluminal growth pattern. In terms of morphology, 74.0% of GCP presented as regular, while 61.5% exhibited an ulcerative mucosa. The most common endoscopic feature was the mucosal lesion type (n = 62, 59.6%), including Ⅱa (n = 29), Ⅱa+Ⅱc (n = 4), and Ⅱc (n = 29), followed by polypoid type (n = 23, 22.1%), submucosal lesion type (n = 17, 16.3%), and thickened mucosa with rough wrinkles type (n = 1, 1.0%). The maximum diameter ranged from 20.9 ± 15.3 mm. The mucosa was the most commonly involved layer (n = 63, 60.6%), followed by the submucosa (n = 40, 38.5%), and muscularis propria (n = 1, 1.0%; Table 1).

We conducted further comparisons of the endoscopic features between the regular (n = 77) and irregular (n = 27) lesions. We found that the irregular lesion group predominantly consisted of mucosal lesion type (n = 17, 63.0%), polypoid type (n = 4, 14.8%), and submucosal lesion type (n = 6, 22.2%; Supplementary Table 1).

Endoscopic resection stands as the primary treatment for GCP. In this study, all 104 patients underwent endoscopic resection, including electric cutting (n = 7, 6.7%), EMR (n = 11, 10.6%), ESD (n = 80, 76.9%), and endoscopic submucosal excavation (n = 6, 5.8%). The suture methods employed included a metal clip (n = 40, 38.5%), nylon rope (n = 1, 1.0%), and a combination of a metal clip and nylon rope (n = 1, 1.0%). The average duration ranged from 73.9 ± 57.5 min. Overall, en-bloc resection was performed for 95 GCP cases (91.3%), and complete resection was achieved in 95 cases (91.3%; Table 1). Further analysis revealed no statistical difference in the rates of en-bloc and complete resection between irregular and regular GCP groups (Supplementary Table 1).

The average duration of hospital stay was 3.4 ± 2.3 d. One patient (1.0%) experienced delayed wound bleeding and required the use of a nylon rope to stop the bleeding. Another patient (1.0%) underwent additional surgery subsequent to endoscopic resection due to pathologic findings indicating invasion of gastric cancer into the submucosa. Recurrence was observed in five patients (4.8%). Among these cases, only one patient had undergone incomplete resection. Ultimately, one patient received treatment through surgery, while the remaining four underwent endoscopic resection (Table 1). Patients undergoing surgery received a pathological diagnosis of gastric cancer, whereas those undergoing endoscopic resection were all diagnosed with GCP without concomitant EGC.

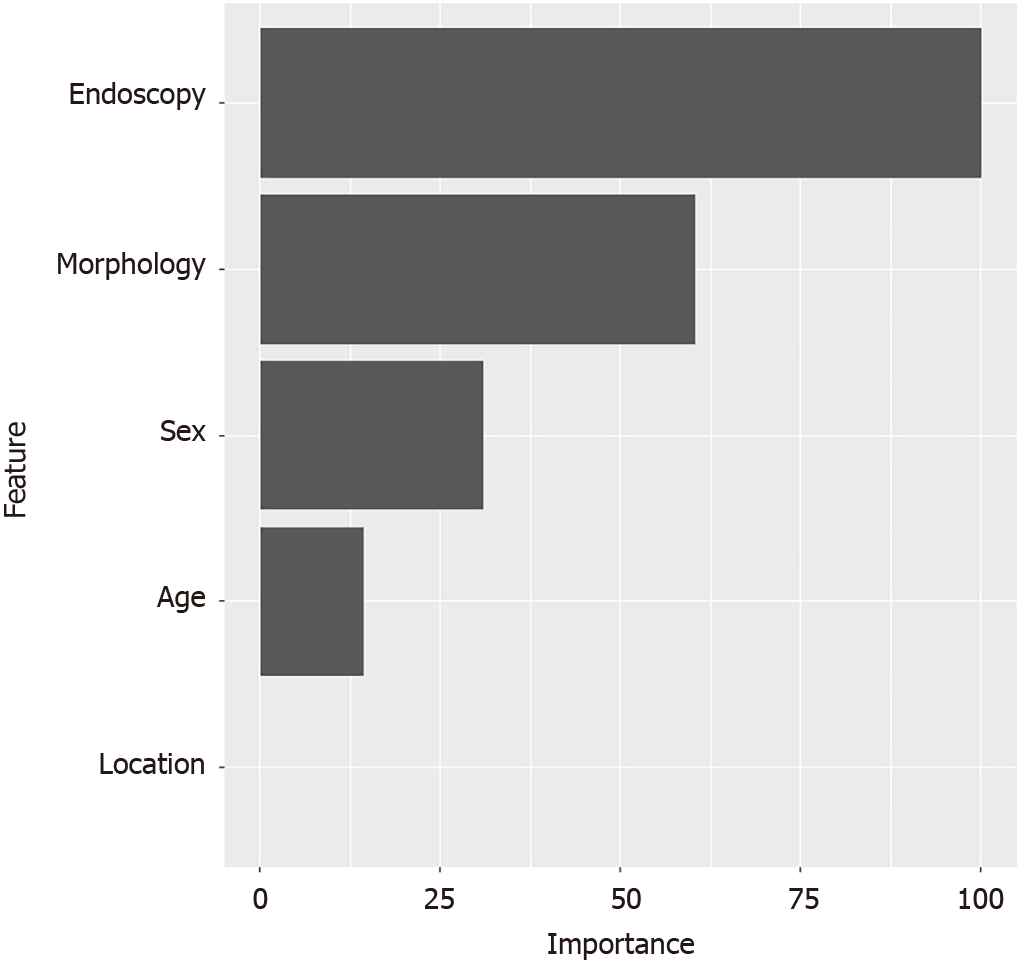

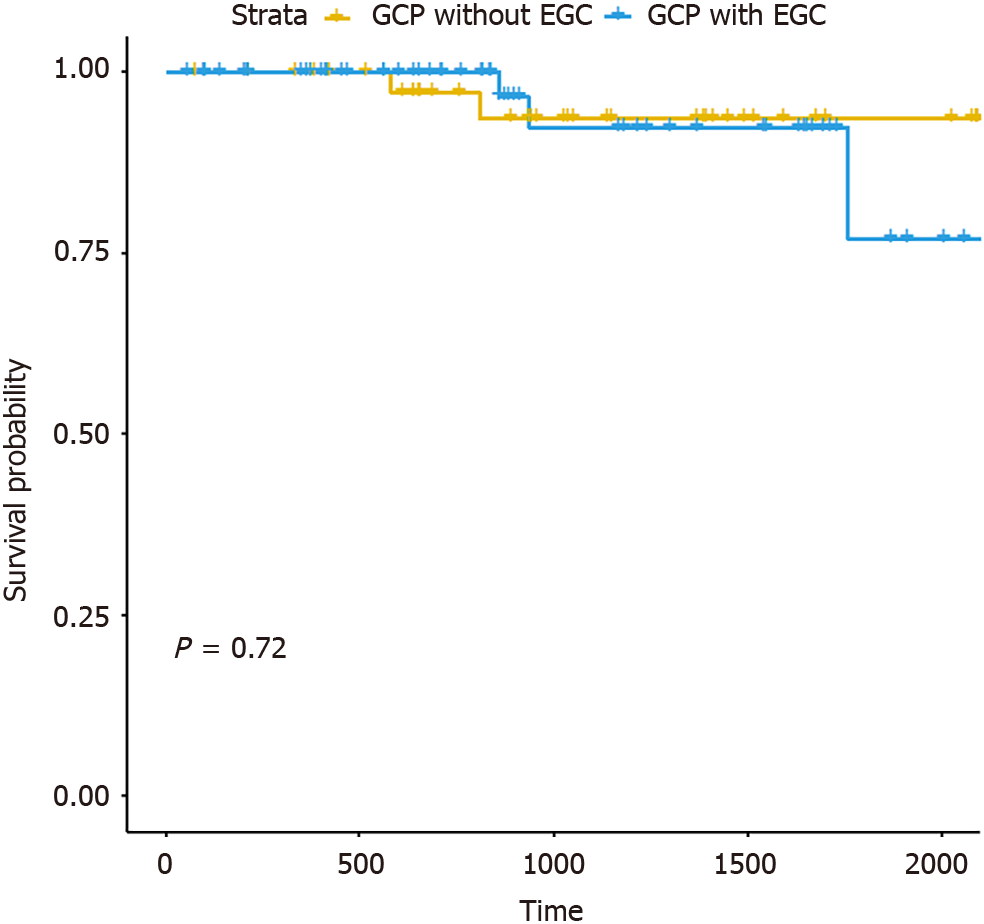

According to the pathologic examination, 59.6% of patients were found to have concomitant EGC. Moreover, we observed significant differences in six variables (sex, age, morphology, mucosa, location, and endoscopic features) between the groups with GCP and those with GCP accompanied by EGC (Table 2). As mucosa and endoscopic features exhibited a significant correlation, the multivariate logistic regression considered five explanatory variables (sex, age, morphology, location, and endoscopic features). The analysis demonstrated that irregular morphology and mucosal lesion type were significant risk factors for GCP accompanied by EGC (P < 0.05; Table 3, Figure 1E and F). The sensitivity analysis depicted the variable importance of risk factors for GCP accompanied by EGC (as shown in Figure 3). Furthermore, survival analysis indicated no statistical difference in recurrence between the groups with GCP accom

| | GCP without EGCs (n = 42) | GCP with EGCs (n = 62) | P value |

| Demographic information | |||

| Male | 23 (54.8) | 54 (87.1) | < 0.001 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 58.5 ± 11.9 | 66.7 ± 9.1 | < 0.001 |

| History of gastric endoscopic or surgical treatment | 4 (9.5) | 9 (14.5) | 0.450 |

| Symptom | 0.158 | ||

| Asymptomatic | 23 (54.8) | 43 (69.4) | |

| Epigastric discomfort | 15 (35.7) | 13 (21.0) | |

| Regurgitation | 4 (9.5) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Melena | 0 (0) | 2 (3.2) | |

| Lesion characteristics | |||

| Growth pattern | 1.000 | ||

| Intraluminal growth | 42 (100) | 61 (98.4) | |

| Extraluminal growth | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Morphology | 0.007 | ||

| Regular | 37 (88.1) | 40 (64.5) | |

| Irregular | 5 (11.9) | 22 (35.5) | |

| Mucosa | < 0.001 | ||

| Smooth | 27 (64.3) | 13 (21.0) | |

| Ulcerative | 15 (35.7) | 49 (79.0) | |

| Max diameter (mm), mean ± SD | 18.0 ± 14.4 | 22.9 ± 15.7 | 0.110 |

| Location | 0.003 | ||

| Cardia | 9 (21.4) | 31 (50.0) | |

| Gastric fundus | 7 (16.7) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Gastric body | 16 (38.1) | 19 (30.6) | |

| Gastric antrum | 10 (23.8) | 11 (17.7) | |

| Endoscopic features | < 0.001 | ||

| Mucosal lesion type | 8 (19.0) | 54 (87.1) | |

| IIa | 6 (75.0) | 23 (42.6) | |

| IIa + IIc | 0 (0) | 4 (7.4) | |

| IIc | 2 (25.0) | 27 (50.0) | |

| Polypoid type | 19 (45.2) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Submucosal lesion type | 13 (31.0) | 4 (6.5) | |

| Thickened mucosa with rough wrinkles type | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0) | |

| Infiltration depth | 0.363 | ||

| Mucosa | 24 (57.1) | 39 (62.9) | |

| Submucosa | 17 (40.5) | 23 (37.1) | |

| Muscularis propria | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Procedural outcomes | |||

| Endoscopic methods | < 0.001 | ||

| Electric cutting | 7 (16.7) | 0 (0) | |

| EMR | 11 (26.2) | 0 (0) | |

| ESD | 18 (42.9) | 62 (100) | |

| ESE | 6 (14.3) | 0 (0) | |

| En-bloc resection | 38 (90.5) | 57 (91.9) | 1.000 |

| Complete resection | 38 (90.5) | 57 (91.9) | 1.000 |

| Suture method | 0.011 | ||

| Unstitched | 18 (42.9) | 44 (71) | |

| Metal clip | 23 (54.8) | 17 (27.4) | |

| Nylon rope | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Metal clip and nylon rope | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | |

| Surgery time (min), mean ± SD | 38.5 ± 38.6 | 96.6 ± 56.3 | < 0.001 |

| Complications | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0) | 0.404 |

| Hospital stay (d), mean ± SD | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 2.5 | 0.006 |

| Additional surgery | 0 (0) | 1 (1.6) | 1.000 |

| Recurrence | 2 (4.8) | 3 (4.8) | 1.000 |

| Factors | Multivariate analysis | ||

| OR [95%CI] | β coefficient | P value | |

| Location | |||

| Cardia | 1 | ||

| Non-cardia | 0.881 [0.226-3.424] | -0.126 | 0.853 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 3.323 [0.771-14.764] | 1.201 | 0.104 |

| Female | 1 | ||

| Morphology | |||

| Regular | 1 | ||

| Irregular | 15.278 [2.965-111.712] | 2.726 | 0.003 |

| Endoscopic features | |||

| Mucosal lesion type | 1 | ||

| Non-mucosal lesion type | 0.029 [0.006-0.108] | -3.531 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.026 [0.968-1.090] | 0.025 | 0.392 |

Given the limited literature and reports on GCP, our research might hold significance in raising awareness of GCP as a high-risk factor for EGC. Clinical differentiation from conditions such as hypertrophic gastritis, mesenchymal tumors, gastric cancer, and ectopic pancreas is crucial. Due to GCP's malignant potential, prompt removal through endoscopy or surgery is essential, coupled with regular postoperative follow-up[11]. In this study, we delineated the endoscopic features of GCP and evaluated the impact of endoscopic resection on the diagnosis and treatment of GCP.

Out of the five patients with GCP who experienced recurrence, only one had a recurrence at the original resection site. The remaining four recurrences occurred at sites distinct from the original resection site. Additionally, the patient who experienced a recurrence at the original site had multiple lesions and was unable to undergo en-bloc resection at that time. Hence, it can be inferred that ESD is effective for lesions necessitating en-bloc resection.

GCP is typically regarded as a benign lesion, yet it can serve as a precancerous gastric condition. Given that GCP is commonly associated with gastric adenocarcinoma or EGC, its malignant potential should be underscored. In our study, we noted that 59.6% of GCP cases were linked with EGC. Through multivariate and sensitivity analyses, irregular morphology and mucosal lesion type emerged as significant risk factors for GCP accompanied by EGC. The mucosal lesion type encompassed Ⅱa (mucosal flat elevation), Ⅱa+Ⅱc (mucosal flat elevation with mild depression), and Ⅱc (mild depression). Considering that EGC typically presents as mucosal lesions, it is evident that GCP featuring mucosal lesion types pose a heightened risk for EGC. An asymmetric expansion of glands in the mucosa and submucosa can lead to irregularities, resulting in the appearance of raised and depressed areas, often accompanied by erosion or ulcers. Consequently, the irregular morphology of GCP is deemed a high-risk factor for EGC. Whenever feasible, we recommend endoscopic resection for GCP, particularly when irregular morphology or mucosal lesion type is apparent, as this signifies a heightened risk of concurrent EGC.

The en-bloc resection and complete resection showed no difference between GCP with EGC and GCP without EGC groups. Additionally, there were no differences in complications, additional surgery, or recurrence between these two groups. These findings suggest that there is no disparity in the efficacy of endoscopic resection for GCP, regardless of the presence or absence of EGC. Therefore, similar to ESD for EGC with infiltration depth ≤ 500 μm, ESD emerges as a safe and effective minimally invasive treatment for GCP, irrespective of the presence of concurrent EGC.

To determine whether the irregular shape of GCP impacted en-bloc and complete resection rates, we compared the rates between groups with regular and irregular shapes. Our analysis revealed no statistically significant difference, suggesting that endoscopy can achieve en-bloc or complete resection even for GCPs with irregular shapes.

Despite the promising results, this study had certain limitations, including a small sample size and potential bias inherent in the retrospective design. Further research is imperative to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the natural progression of GCP and its malignant potential.

In summary, irregular shapes and mucosal lesion types observed during endoscopy might serve as high-risk factors for GCP with EGC. Future studies should aim to clarify the disease's natural progression and its malignant potential. Notably, ESD might be a secure and efficacious minimally invasive treatment, regardless of the presence of EGC.

The findings suggested that endoscopic resection might serve as an effective and minimally invasive treatment for GCP with or without EGC.

Gastric cystica profunda (GCP) is an uncommon gastric lesion characterized by hyperplasia of connective tissues within the interstitium of the glands, involving the submucosal layer or even the muscularis propria of the stomach. Widespread chronic active or atrophic gastritis is considered a significant factor contributing to GCP. Patients with GCP may either be asymptomatic or present with non-specific digestive symptoms such as abdominal pain and belching. Due to the indistinct clinical characteristics and non-specific endoscopic manifestations, most clinicians have limited understanding of GCP. Additionally, GCP has been regarded as a potential premalignant lesion. Endoscopic identification of irregular shapes and mucosal lesion types may serve as high-risk factors for GCP associated with early gastric cancer (EGC). Irrespective of EGC presence, endoscopic submucosal dissection emerges as a secure and effective minimally invasive treatment.

Patients with GCP may either remain asymptomatic or present with non-specific digestive symptoms, including abdominal pain and belching. Owing to the unremarkable clinical characteristics and nonspecific endoscopic manifestations, most clinicians possess limited understanding of GCP. Furthermore, GCP has been regarded as a potential premalignant lesion; hence, the endoscopic diagnosis and early excision of GCP are deemed crucial. In this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 104 cases of GCP treated by endoscopic resection at our center from October 2011 to December 2022. Our analysis was based on their clinical manifestations, endoscopic findings, pathological results, and treatments. The primary objectives were to delineate the endoscopic features of GCP associated with EGC and to assess the impact of endoscopic resection on the diagnosis and treatment of GCP with EGC.

Given the limited literature and reports on GCP, our research might hold significance in raising awareness of GCP as a high-risk factor for EGC. Clinical differentiation from conditions such as hypertrophic gastritis, mesenchymal tumors, gastric cancer, and ectopic pancreas is crucial. Due to GCP's malignant potential, prompt removal through endoscopy or surgery is essential, coupled with regular postoperative follow-up. In this study, we delineated the endoscopic features of GCP and evaluated the impact of endoscopic resection on the diagnosis and treatment of GCP.

This retrospective study involved 104 patients with GCP who underwent endoscopic resection. Alongside demographic and clinical data, regular patient follow-ups were conducted to assess local recurrence.

Among the 104 patients diagnosed with GCP who underwent endoscopic resection, 12.5% had a history of previous gastric procedures. The primary site predominantly affected was the cardia (38.5%, n = 40). GCP commonly exhibited intraluminal growth (99%), regular presentation (74.0%), and ulcerative mucosa (61.5%). The leading endoscopic feature was the mucosal lesion type (59.6%, n = 62). The average maximum diameter was 20.9 ± 15.3 mm, with mucosal involvement in 60.6% (n = 63). Procedures lasted 73.9 ± 57.5 min, achieving complete resection in 91.3% (n = 95). Recurrence (4.8%) was managed via either surgical intervention (n = 1) or through endoscopic resection (n = 4). Final pathology confirmed that 59.6% of GCP cases were associated with EGC. Univariate analysis indicated that elderly males were more susceptible to GCP associated with EGC. Conversely, multivariate analysis identified lesion morphology and endoscopic features as significant risk factors. Survival analysis demonstrated no statistically significant difference in recurrence between GCP with and without EGC (P = 0.72).

The findings suggested that endoscopic resection might serve as an effective and minimally invasive treatment for GCP with or without EGC.

Further research is imperative to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the natural progression of GCP and its malignant potential.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Shahidi N, Canada S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li L

| 1. | Littler ER, Gleibermann E. Gastritis cystica polyposa. (Gastric mucosal prolapse at gastroenterostomy site, with cystic and infiltrative epithelial hyperplasia). Cancer. 1972;29:205-209. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Lee TH, Lee JS, Jin SY. Gastritis cystica profunda with a long stalk. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:821-2; discussion 822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (113)] |

| 3. | Xu G, Peng C, Li X, Zhang W, Lv Y, Ling T, Zhou Z, Zhuge Y, Wang L, Zou X, Zhang X, Huang Q. Endoscopic resection of gastritis cystica profunda: preliminary experience with 34 patients from a single center in China. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;81:1493-1498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Wang R, Lu H, Yu J, Huang W, Li J, Cheng M, Liang P, Li L, Zhao H, Gao J. Computed tomography features and clinical characteristics of gastritis cystica profunda. Insights Imaging. 2022;13:14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wu JJ, Cheng YQ, Yang HJ, Lin M. Correlation between gastritis cystica profunda and the risk of lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer. Neoplasma. 2022;69:1459-1465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Park CH, Park JM, Jung CK, Kim DB, Kang SH, Lee SW, Cho YK, Kim SW, Choi MG, Chung IS. Early gastric cancer associated with gastritis cystica polyposa in the unoperated stomach treated by endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:e47-e50. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wahi JE, Pagacz M, Ben-David K. Gastric Adenocarcinoma Arising in a Background of Gastritis Cystica Profunda. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:2387-2388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Park JS, Myung SJ, Jung HY, Yang SK, Hong WS, Kim JH, Kang GH, Ha HK, Min YI. Endoscopic treatment of gastritis cystica polyposa found in an unoperated stomach. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:101-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fong TV, Chuah SK, Chiou SS, Chiu KW, Hsu CC, Chiu YC, Wu KL, Chou YP, Ong GY, Changchien CS. Correlation of the morphology and size of colonic polyps with their histology. Chang Gung Med J. 2003;26:339-343. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Wang L, Yan H, Cao DC, Huo L, Huo HZ, Wang B, Chen Y, Liu HL. Gastritis cystica profunda recurrence after surgical resection: 2-year follow-up. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (111)] |