Published online Dec 21, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i47.5007

Revised: October 25, 2024

Accepted: October 31, 2024

Published online: December 21, 2024

Processing time: 81 Days and 16.4 Hours

Submucosal invasion in early-stage gastric cancer (GC) is a critical determinant of prognosis and treatment strategy, significantly influencing the risk of lymph node metastasis and recurrence. Identifying risk factors associated with submucosal invasion is essential for optimizing patient management and improving out

To comprehensively analyze clinical, imaging, and endoscopic characteristics to identify predictors of submucosal invasion in patients with early-stage differentiated GC.

A retrospective study was conducted at our institution from January 2019 to January 2023, including 268 patients diagnosed with early-stage differentiated GC who underwent surgical resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection. Data were collected on demographic, clinical, imaging, and endoscopic characteristics, with endoscopic images reviewed independently by two gastroenterologists. Statistical analysis included univariate and multivariate logistic regression to identify significant predictors of submucosal invasion, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate the predictive value of continuous variables.

A total of 268 patients were included, with 178 males and 90 females, and a mean age of 61.5 ± 9.8 years. Univariate analysis showed that male gender, history of alcohol consumption, smoking, and computed tomography-detected gastric wall thickening were more prevalent in patients with submucosal invasion. Significant endoscopic predictors included tumor location in the upper two-thirds of the stomach, depressed morphology, marginal elevation, and high color differences on white-light endoscopy (WLE) and linked color imaging (LCI). Multivariate analysis identified upper stomach location [odds ratio (OR): 5.268], depressed type (OR: 5.841), marginal elevation (OR: 4.132), and LCI color difference ≥ 18.1 (OR: 4.479) as significant predictors. ROC analysis showed moderate predictive value for lesion diameter, WLE, and LCI color differences (area under the curve: 0.630, 0.799, and 0.760, respectively).

Depressed-type lesions, marginal elevation, location in the upper two-thirds of the stomach, and significant color differences on LCI are high-risk indicators for submucosal invasion. These findings suggest that such lesions warrant more aggressive intervention to prevent disease progression and improve patient outcomes.

Core Tip: Our research provides an in-depth analysis of multiple risk factors that influence submucosal invasion in early-stage gastric cancer, which is pivotal for determining prognosis and tailoring treatment strategies. This retrospective study, conducted over four years at our institution, integrates a broad spectrum of data points-including clinical, imaging, and endoscopic characteristics-to identify significant predictors of submucosal invasion. Our findings underscore the importance of specific endoscopic features and demographic factors in predicting the depth of tumor invasion, thereby aiding in the clinical decision-making process.

- Citation: Yan BB, Cheng LN, Yang H, Li XL, Wang XQ. Comprehensive analysis of risk factors associated with submucosal invasion in patients with early-stage gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(47): 5007-5017

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i47/5007.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i47.5007

Gastric cancer (GC) continues to pose a major global health challenge, ranking among the foremost causes of cancer-related mortality globally. Notwithstanding progress in diagnostic technologies and treatment approaches, the prognosis for GC, especially in its advanced stages, continues to be unfavorable[1-3]. Nevertheless, early identification and intervention have demonstrated potential in enhancing survival rates. A proportion of patients diagnosed with early-stage stomach cancer demonstrates submucosal invasion, when the tumor penetrates past the mucosal layer into the submucosa. The invasion is a crucial element that profoundly affects clinical care, prognosis, and treatment decisions for patients. Early-stage stomach cancer is generally restricted to the mucosa and submucosa, irrespective of lymph node involvement. The conventional treatment method for early-stage GC has typically been endoscopic excision, particularly when the tumor is limited to the mucosal layer[4-6]. The occurrence of submucosal invasion raises concerns since it is linked to an increased chance of lymph node metastasis, resulting in a more aggressive disease progression and requiring more extensive surgical procedures.

Submucosal invasion in early-stage GC is a heterogeneous phenomena driven by numerous factors. These factors encompass the depth of invasion, histological type, presence of lymphovascular invasion, and tumor size, among others. The precise mechanisms and routes resulting in submucosal invasion remain incompletely elucidated; however, it is evident that these elements significantly influence the tumor's biological activity[7,8]. The identification and thorough study of these risk variables are essential for enhancing patient outcomes, as they can assist clinicians in customizing treatment regimens, including the choice between endoscopic resection and more radical surgical methods. Recent investigations have emphasized the need of comprehending the risk variables linked to submucosal invasion in early-stage GC[9,10]. Certain histological features, including poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma, the presence of signet ring cells, and diffuse-type GC, have been recognized as having a higher propensity for submucosal invasion. Molecular markers and genetic abnormalities are emerging as potential factors influencing the likelihood of deeper invasion, however further work is necessary in these domains.

The management of early-stage GC is evolving, making the proper identification and mitigation of risk factors related to submucosal invasion critically important. This study aims to address information deficiencies by conducting a comprehensive analysis of these risk factors, with the ultimate goal of refining treatment options and improving survival rates for patients with early-stage GC.

A retrospective analysis was undertaken at our institution to examine the risk factors linked to submucosal invasion in patients with early-stage GC. This study covered the period from January 2019 to January 2023, with 268 patients who received surgical resection or endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD) for early-stage stomach cancer at our institution. The study's design, aims, and protocols were meticulously formulated in accordance with the STROBE guidelines[11]. The study received ethical approval from the hospital's Ethics Committee, guaranteeing that all research operations adhered to ethical norms while prioritizing patient safety and anonymity.

Inclusion criteria: (1) Diagnosis of early-stage GC: Patients with histologically diagnosed early-stage stomach cancer, characterized by malignancy limited to the mucosa or submucosa, irrespective of lymph node involvement; (2) Treatment with surgical resection or ESD: Only patients who have received surgical resection or ESD as their primary treatment at our institution; (3) Complete medical records: Patients possessing complete clinical, pathological, and follow-up data for thorough study; and (4) Age criteria: Individuals aged 18 years and older at the time of diagnosis.

Exclusion criteria: (1) Previous GC treatment: Patients who underwent any treatment for stomach cancer before the research period, including chemotherapy, radiation, or surgery; (2) Metastatic disease: Patients exhibiting signs of metastatic GC at diagnosis or during the research duration; (3) Inadequate sample quality: Instances in which the pathological specimens were considered insufficient for a comprehensive histological evaluation; and (4) Concurrent malignancies: Patients have a history of other malignancies in the past five years, except non-melanoma skin cancer and in situ cervical cancer.

In this study, comprehensive baseline information was collected for each patient, including demographic and clinical data such as gender, age, smoking history, alcohol consumption history, and family history of GC.

Smoking and alcohol consumption history: These were documented based on the medical records, ensuring consistency in data collection.

Family history of GC: Defined by the presence of GC in first-degree relatives, as recorded in the patient’s medical history.

Laboratory and imaging data: Key laboratory results, including hemoglobin levels, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and fecal occult blood tests, were recorded from the initial tests performed after hospital admission. Hemoglobin levels were used to assess anemia, defined as < 120 g/L in males and < 110 g/L in females, according to the hospital's laboratory reference standards. An elevated CEA was defined as a value greater than 5 ng/mL. Positive fecal occult blood results included both positive and weakly positive findings.

Imaging findings: Preoperative abdominal contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans were reviewed to assess gastric wall thickening and lymph node enlargement. Gastric wall thickening was defined as the presence of abnormal enhancement or thickening observed on the CT report, while lymph node enlargement was defined as the identification of abnormal lymph nodes surrounding the stomach.

Histopathological evaluation: Preoperative biopsy results were classified as either dysplasia or carcinoma based on the hospital’s pathology reports or pathology consultation records. If no pathology report from our hospital was available, the diagnosis from the external pathology report recorded in the medical history was used. The depth of tumor invasion was documented from the postoperative pathology reports following ESD or surgical resection.

To precisely evaluate the endoscopic characteristics of the lesions, we methodically extracted original endoscopic images and reports from our hospital's gastroenterology image database. The investigation utilized patient identifiers including name, age, and surgery date. The photos and reports were acquired from white-light endoscopy (WLE) and linked color imaging (LCI) examinations. The documented endoscopic characteristics encompassed the lesion's location, gross categorization, diameter, occurrence of spontaneous bleeding, central depression, stomach wall rigidity, border elevation, alterations in folds, ulceration, and surface roughness. A senior gastroenterologist, blinded to the postoperative pathological outcomes, independently evaluated the endoscopic pictures to confirm the correctness of the feature assessment. The results were subsequently compared with the first endoscopic report. If the independent assessment aligned with the original report, the characteristics were directly incorporated into the research. In instances of discrepancy, a second senior gastroenterologist performed an independent evaluation. The conclusive assessment of the endoscopic characteristics was established by a consensus methodology, guaranteeing that a minimum of two gastroenterologists concurred on each feature prior to its inclusion in the study.

Lesion location and gross classification: Lesion location and gross classification were determined using the Japanese classification of early GC[12]. Lesion locations were categorized into three sections: Upper third, middle third, and lower third of the stomach. Gross classification was divided into three types: Elevated (types I, IIa, and IIa + IIc without ulceration), flat (type IIb), and depressed (including types IIc, III, IIc + IIa, IIa + IIc with ulceration).

Lesion diameter: The lesion diameter was estimated by the endoscopist, using reference points such as the diameter of the endoscope (8-12 mm), the thickness of the biopsy forceps when open (approximately 1 mm), and when closed (approximately 3 mm). Measurements were recorded to the nearest millimeter and documented in the endoscopic report.

Spontaneous bleeding: Spontaneous bleeding was defined as bleeding from the lesion observed without any preceding biopsy or other endoscopic manipulation.

Central depression: Central depression was defined as a depression observed at the center of an elevated-type lesion.

Gastric wall rigidity: Gastric wall rigidity referred to reduced softness or diminished peristalsis of the gastric wall, characterized by decreased compliance upon inflation during endoscopy.

Marginal elevation: Based on Yao et al's research, marginal elevation was defined as a trapezoidal elevation of the lesion itself or the convergence and elevation of mucosal folds when observed at an angle of 15° to 45° with the gastric wall fully distended[7].

Fold changes: Fold changes were defined as the thickening, fusion, or disruption of mucosal folds surrounding the lesion.

Ulceration: Both active and scar-phase ulcers were defined as the presence of any ulceration within the lesion.

Surface roughness: Surface roughness was characterized by a granular or nodular uneven surface texture of the lesion.

The color difference evaluation involved exporting the WLE and LCI images of the lesions from the endoscope system, as indicated in the endoscopic reports. The lesion margins were defined according to the report descriptions and validated by two independent endoscopists' reviews. Five random coordinate points were produced by computer within the specified lesion area, and their average value was computed. If any of these locations coincided with regions exhibiting bleeding or obscured by white exudates, fresh random points were generated. Two random coordinate coordinates were selected from the surrounding mucosa, and their average value was computed. The study utilized the Commission Internationale de l’Eclairage Lab* color space measurement method to quantitatively examine the color metrics and objectively calculate the color difference between the malignant region and the adjacent mucosa. This technique encompasses the three-dimensional color space, with the L* axis denoting luminance, the a* axis indicating the red-green spectrum, and the b* axis representing the yellow-blue spectrum. All photos were examined utilizing Adobe Photoshop software to guarantee uniformity in the L*, a*, and b* axis measurements. Under the assumption of constant brightness, the color difference was determined using the values along the a* and b* axes, yielding an accurate quantitative assessment of the color disparity between the lesion and the adjacent tissue.

The statistical analysis was conducted utilizing SPSS version 27.0 and R Studio software. The χ2 test was employed for comparisons of categorical variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was utilized to evaluate the normality of continuous variables. For data conforming to a normal distribution, results were expressed as mean ± SD, with group comparisons performed using the independent samples t-test. For data that deviated from a normal distribution, results were presented as median (interquartile range, and the Mann-Whitney U test was utilized for group comparisons. A univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to ascertain possible predictors. The ideal cutoff values for continuous variables were established by receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to assess their predictive capacity for the depth of invasion. Factors demonstrating significant differences in the univariate study were later incorporated into a multivariate logistic regression model employing a stepwise forward selection approach. Multicollinearity among variables was assessed to verify the model's robustness. A two-tailed P-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

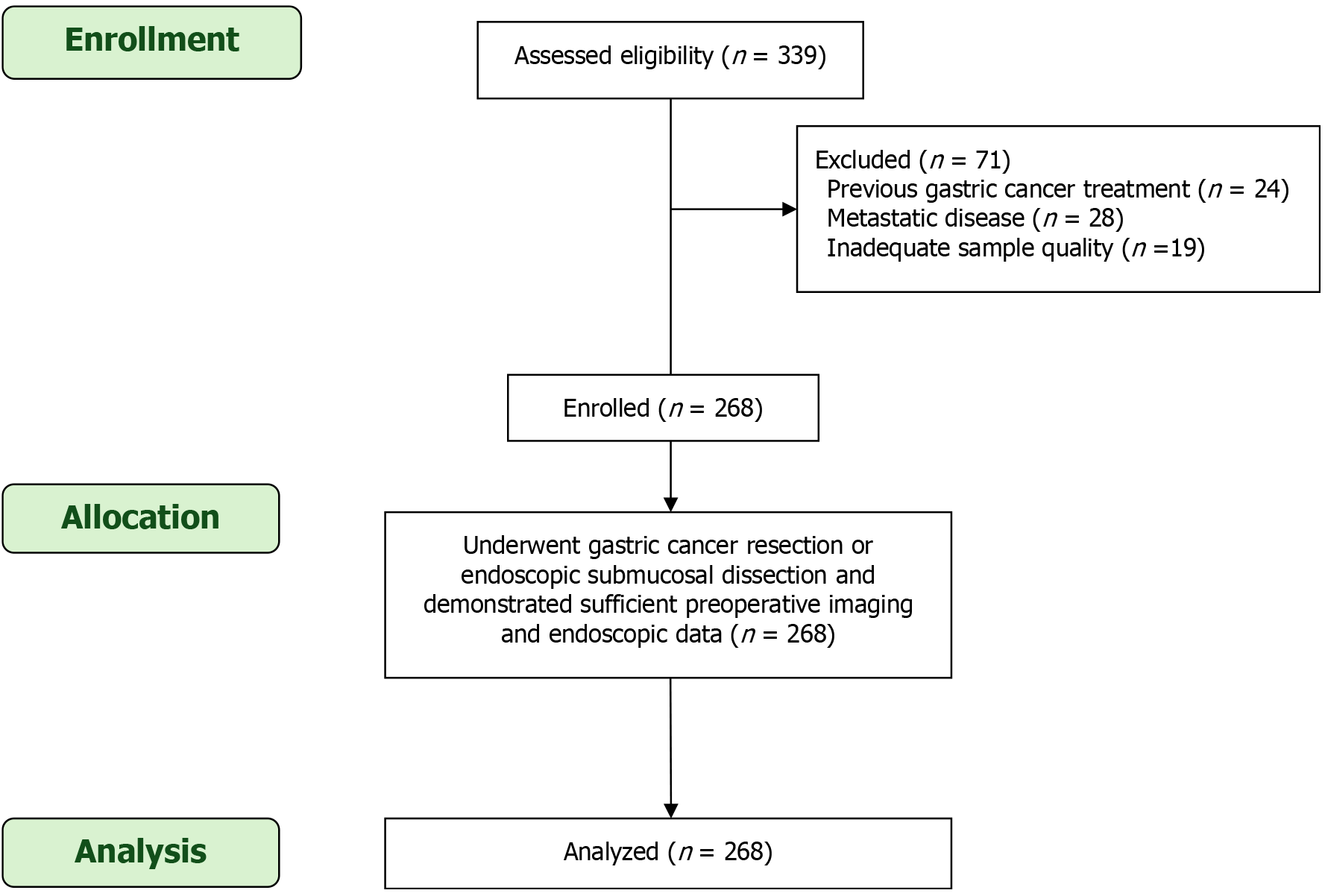

As illustrated in Figure 1, the flowchart summarizes the patient selection process for the study evaluating risk factors associated with submucosal invasion in early-stage GC. A total of 339 patients were initially assessed for eligibility. Of these, 71 patients were excluded based on the following criteria: 24 patients had previously undergone GC treatment, 28 presented with metastatic disease at diagnosis, and 19 had inadequate sample quality for accurate histopathological evaluation. After these exclusions, 268 patients were enrolled in the study and underwent GC resection or ESD, with complete preoperative imaging and endoscopic data available for analysis. All 268 patients were included in the final analysis, ensuring a comprehensive evaluation of clinical, endoscopic, and imaging factors related to submucosal invasion.

This study included a total of 268 patients diagnosed with early-stage differentiated GC. Of these, 178 were male (66.4%) and 90 were female (33.6%), with ages ranging from 30 to 83 years and a mean age of 61.5 ± 9.8 years. A significant proportion of the cohort (189 patients, 70.5%) were aged 60 years or older, highlighting the higher prevalence of GC in the elderly population. Lifestyle factors were notable in this cohort, with 101 patients (37.7%) having a history of alcohol consumption and 136 patients (50.7%) reporting a history of smoking. Additionally, a family history of GC was identified in 37 patients (13.8%), suggesting a possible hereditary component in a subset of cases. Clinical assessments revealed that 11 patients (4.1%) were anemic, 53 patients (19.8%) tested positive for fecal occult blood, and elevated CEA levels were detected in 19 patients (7.1%). Imaging studies using preoperative CT scans showed gastric wall thickening in 111 patients (41.4%), a feature often associated with more advanced disease or deeper invasion. Endoscopic examination of all patients revealed solitary lesions, with their location distributed as follows: 61 cases (22.8%) in the upper third of the stomach, 43 cases (16.0%) in the middle third, and the majority, 164 cases (61.2%), in the lower third. The gross morphological classification of these lesions indicated that 139 cases (51.9%) were of the elevated type, 51 cases (19.0%) were flat, and 78 cases (29.1%) were depressed (Table 1).

| Characteristic | n (%) |

| Total patients | 268 |

| Gender | |

| Male | 199 (72.3) |

| Female | 69 (25.7) |

| Age (years) | |

| mean ± SD | 61.5 ± 9.8 |

| Age range | 30-83 |

| Age ≥ 60 years | 192 (71.6) |

| Lifestyle factors | |

| History of alcohol consumption | 143 (53.4) |

| History of smoking | 152 (56.7) |

| Family history of gastric cancer | 37 (13.8) |

| Clinical assessments | |

| Anemia | 12 (4.5) |

| Positive fecal occult blood test | 60 (22.4) |

| Elevated CEA | 19 (7.1) |

| Imaging findings | |

| CT showing gastric wall thickening | 111 (41.4) |

| CT showing lymph node enlargement | 34 (12.7) |

| Endoscopic characteristics | |

| Lesion location | |

| Upper third of the stomach | 87 (32.5) |

| Middle third of the stomach | 41 (15.3) |

| Lower third of the stomach | 140 (52.2) |

| Gross morphology | |

| Elevated type | 144 (53.7) |

| Flat type | 51 (19.0) |

| Depressed type | 73 (27.2) |

The univariate analysis revealed that male gender, a history of alcohol consumption, and smoking were more prevalent among patients with submucosal invasion compared to those with mucosal invasion. A significantly higher proportion of males (85.9%) was observed in the submucosal group compared to the mucosal group (70.1%), though this difference did not reach statistical significance. However, both a history of alcohol consumption (60.6% vs 50.8%, P < 0.05) and smoking (63.4% vs 54.3%, P < 0.05) were significantly more common in patients with submucosal invasion. The age and family history of GC did not show significant differences between the two groups.

Among the clinical and imaging findings, CT evidence of gastric wall thickening was significantly associated with submucosal invasion (59.2% vs 35.0%, P < 0.05), suggesting that this feature could be an important predictor of deeper invasion. Although other variables, such as anemia, positive fecal occult blood tests, and elevated CEA levels, were examined, they did not demonstrate significant differences between the groups. Additionally, CT evidence of lymph node enlargement was more common in the submucosal invasion group (22.5% vs 9.1%), but the difference did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.107).

Endoscopic characteristics showed the most substantial differences between the two groups. Tumor location in the upper third of the stomach was strongly associated with submucosal invasion (71.8% vs 18.3%, P < 0.01), making it a strong predictor. In contrast, tumors located in the lower third of the stomach were more commonly associated with mucosal invasion (66.0% vs 14.1%).

Gross morphology also emerged as a significant factor. Patients with submucosal invasion were more likely to have depressed-type lesions (56.3% vs 16.8%, P < 0.001), while the elevated-type lesions were more prevalent in the mucosal invasion group (47.4% vs 23.9%, P < 0.001). Marginal elevation (36.6% vs 14.2%, P < 0.01) and fold changes (16.9% vs 8.1%, P < 0.05) were also significantly more frequent in the submucosal invasion group.

While the lesion diameter and the presence of ulcers approached statistical significance, they did not reach the threshold for significance (P = 0.052 and P = 0.103, respectively).

Additionally, color differences assessed through WLE and LCI were notably higher in the submucosal invasion group. Significant differences were observed for WLE color difference (42.3% vs 41.6%, P < 0.01) and LCI color difference (71.8% vs 48.2%, P < 0.01), indicating that advanced endoscopic imaging techniques can help distinguish between submucosal and mucosal invasions based on color variations (Table 2).

| Characteristic | Submucosal invasion (n = 71) | Mucosal invasion (n = 197) | χ² (t, Z) value | P value | OR (95%CI) | P value |

| Demographics and medical history | ||||||

| Male | 61 (85.9) | 138 (70.1) | χ² = 1.509 | 0.122 | 1.90 (0.70-5.75) | 0.228 |

| Age ≥ 60 years | 52 (73.2) | 140 (71.1) | χ² = 0.251 | 0.615 | 0.85 (0.31-2.75) | 0.634 |

| Age (years) | 62.9 ± 10.5 | 64.3 ± 10.2 | t = 1.132 | 0.272 | 0.94 (0.91-1.23) | 0.352 |

| Alcohol history | 43 (60.6) | 100 (50.8) | χ² = 4.738 | < 0.05 | 2.25 (1.25-5.94) | < 0.05 |

| Smoking history | 45 (63.4) | 107 (54.3) | χ² = 4.342 | < 0.05 | 2.56 (1.15-6.44) | < 0.05 |

| Family history of gastric cancer | 10 (14.1) | 27 (13.7) | χ² = 0.314 | 0.532 | 0.63 (0.33-1.97) | 0.517 |

| Clinical and imaging findings | ||||||

| Anemia | 4 (5.6) | 8 (4.1) | χ² = 0.342 | 0.643 | 2.55 (0.45-11.82) | 0.275 |

| Positive fecal occult blood test | 16 (22.5) | 44 (22.3) | χ² = 0.692 | 0.548 | 0.58 (0.28-1.23) | 0.462 |

| Elevated CEA | 4 (5.6) | 15 (7.6) | χ² = 0.012 | 0.913 | 1.39 (0.63-6.34) | 0.649 |

| CT showing gastric wall thickening | 42 (59.2) | 69 (35.0) | χ² = 6.784 | < 0.05 | 3.10 (1.40-7.25) | 0.026 |

| CT showing lymph node enlargement | 16 (22.5) | 18 (9.1) | χ² = 2.954 | 0.107 | 3.21 (0.85-8.96) | 0.109 |

| Endoscopic characteristics | ||||||

| Tumor location: Upper third | 51 (71.8) | 36 (18.3) | χ² = 28.231 | < 0.01 | 18.25 (6.41-56.16) | < 0.001 |

| Middle third | 10 (14.1) | 31 (15.7) | ||||

| Lower third of the stomach | 10 (14.1) | 130 (66.0) | ||||

| Gross type: Elevated type | 17 (23.9) | 127 (47.4) | χ² = 18.400 | < 0.001 | 5.50 (2.19-14.32) | < 0.01 |

| Flat type | 14 (19.7) | 37 (18.8) | ||||

| Depressed type | 40 (56.3) | 33 (16.8) | ||||

| Lesion diameter ≥ 20 mm | 16 (22.5) | 44 (22.3) | χ² = 3.741 | 0.052 | 2.46 (0.96-5.82) | 0.072 |

| Lesion diameter (mm) | 20 (12, 32) | 15 (13, 21) | Z = 1.742 | 0.071 | 1.13 (0.97-1.15) | 0.089 |

| Spontaneous bleeding | 6 (8.5) | 21 (10.7) | χ² = 0.274 | 0.795 | 1.53 (0.54-4.69) | 0.579 |

| Central depression | 9 (12.7) | 33 (16.8) | χ² = 0.894 | 0.324 | 1.67 (0.64-4.86) | 0.371 |

| Gastric wall rigidity | 8 (11.3) | 12 (6.1) | χ² = 0.505 | 0.493 | 2.63 (0.89-30.25) | 0.517 |

| Marginal elevation | 26 (36.6) | 28 (14.2) | χ² = 10.646 | 0.002 | 4.10 (1.58-9.65) | 0.006 |

| Fold changes | 12 (16.9) | 16 (8.1) | χ² = 3.774 | 0.081 | 11.83 (3.25-35.61) | 0.018 |

| Presence of ulcer | 12 (16.9) | 48 (24.3) | χ² = 2.773 | 0.103 | 1.75 (0.78-4.03) | 0.254 |

| Surface roughness | 44 (62.0) | 126 (64.0) | χ² = 1.222 | 0.243 | 1.58 (0.70-4.15) | 0.302 |

| WLE color difference ≥ 12.6 | 30 (42.3) | 82 (41.6) | χ² = 9.500 | < 0.01 | 5.00 (1.66-12.77) | < 0.01 |

| WLE color difference | 18.1 (12.6, 20.3) | 13.2 (9.8, 22.1) | Z = 3.630 | < 0.01 | 1.40 (1.14-1.58) | < 0.01 |

| LCI color difference ≥ 18.1 | 51 (71.8) | 95 (48.2) | χ² = 11.731 | < 0.01 | 4.27 (1.82-10.11) | < 0.01 |

| LCI color difference | 26.8 (19.1, 34.2) | 18.6 (14.1, 23.1) | Z = 3.226 | < 0.01 | 1.13 (0.96-1.06) | < 0.01 |

The multivariate logistic regression analysis identified several significant predictors for submucosal invasion in patients with GC. Tumor location in the upper two-thirds of the stomach emerged as the most significant predictor, with an odds ratio (OR) of 5.268 [95% confidence interval (CI): 2.434-10.984], indicating that tumors in this region are over five times more likely to invade the submucosa compared to those in other locations. The gross morphological appearance of the tumor also played a critical role, particularly for the depressed type, which was associated with a substantially increased risk of submucosal invasion (OR: 5.841; 95%CI: 1.745-21.243). This suggests that tumors with a depressed morphology are nearly six times more likely to exhibit deeper invasion compared to other types. Another significant predictor was the presence of marginal elevation, with an OR of 4.132 (95%CI: 1.235-15.869), highlighting that tumors with this characteristic have a markedly higher likelihood of submucosal invasion. Finally, a high color difference on LCI was also a significant predictor. Patients with an LCI color difference of ≥ 18.1 had a significantly increased risk of submucosal invasion (OR: 4.479; 95%CI: 1.274-14.856). This underscores the utility of advanced endoscopic imaging techniques in identifying high-risk lesions (Table 3).

| Characteristic | β value | Standard error | Wald χ² value | P value | OR (95%CI) |

| Tumor located in upper 2/3 of stomach | 1.622 | 0.403 | 18.542 | < 0.001 | 5.268 (2.434-10.984) |

| Depressed type | 1.846 | 0.689 | 7.625 | 0.006 | 5.841 (1.745-21.243) |

| Marginal elevation | 1.398 | 0.624 | 4.662 | 0.027 | 4.132 (1.235-15.869) |

| LCI color difference ≥ 18.1 | 1.489 | 0.672 | 5.427 | 0.021 | 4.479 (1.274-14.856) |

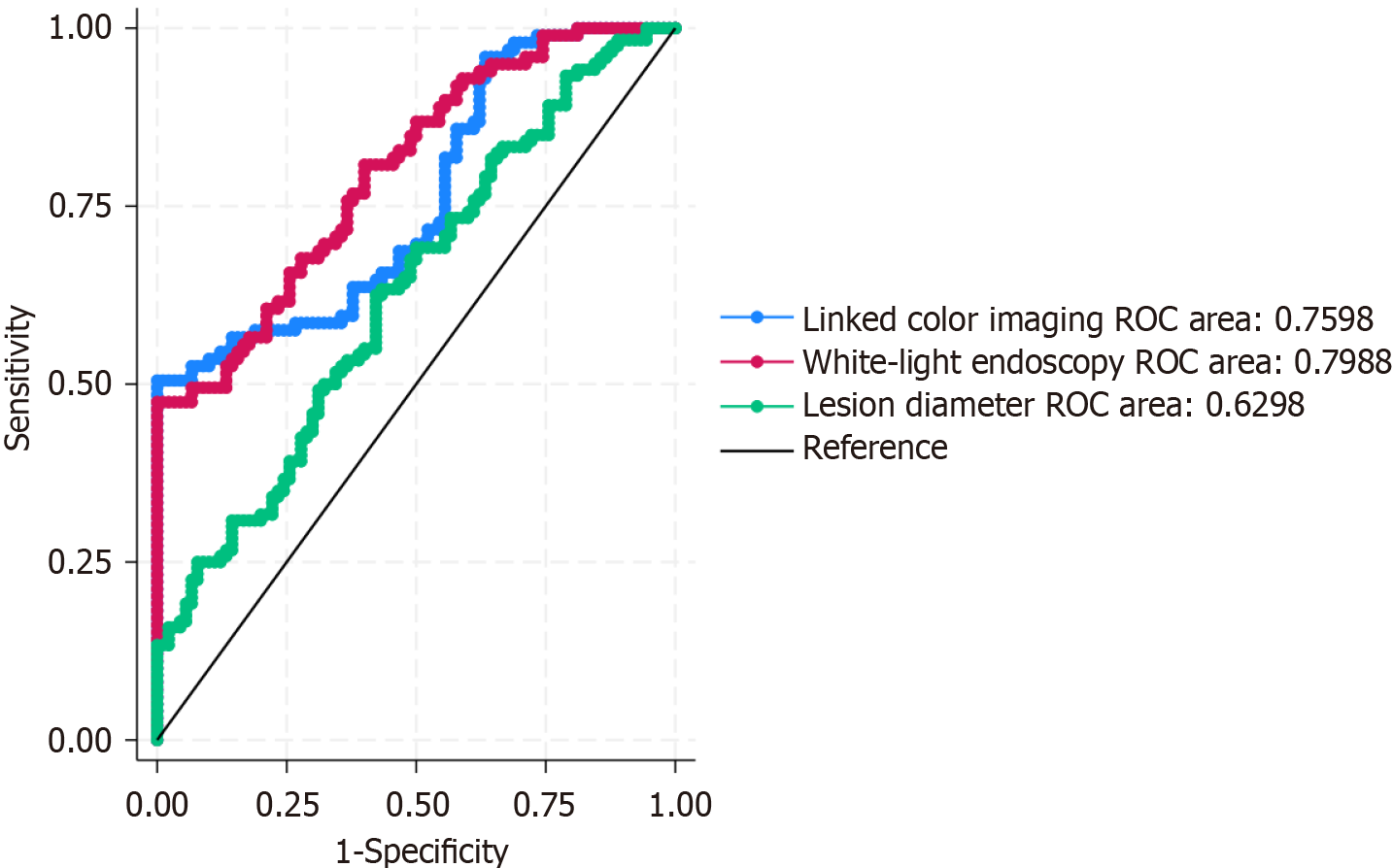

The predictive value of lesion diameter, WLE color difference, and LCI color difference for submucosal invasion in GC was evaluated using ROC curve analysis. As illustrated in Figure 2, the area under the curve (AUC) for lesion diameter, WLE color difference, and LCI color difference were 0.630, 0.799, and 0.760, respectively. These results indicate that each of these indicators possesses a moderate level of predictive value for identifying submucosal invasion.

Given the objective of the study to improve the identification rate of high-risk patients for submucosal invasion while minimizing the likelihood of missed diagnoses, the cutoff values were selected to balance specificity with an emphasis on maximizing sensitivity. Accordingly, the optimal cutoff values determined for lesion diameter, WLE color difference, and LCI color difference were set at 21.1 mm, 13.1, and 17.3, respectively (Table 4).

| Indicator | AUC (95%CI) | Youden index maximum cutoff | Selected cutoff | Sensitivity at cutoff | Specificity at cutoff |

| Lesion diameter | 0.630 (0.462-0.712) | 26.80 | 21.1 | 0.593 | 0.582 |

| WLE color difference | 0.799 (0.642-0.842) | 14.2 | 13.1 | 0.823 | 0.484 |

| LCI color difference | 0.760 (0.571-0.791) | 19.9 | 17.3 | 0.788 | 0.448 |

Submucosal invasion in early-stage GC is a pivotal feature that substantially affects the clinical care and prognosis of patients. Notwithstanding progress in diagnostic and therapeutic methods, identifying patients at elevated risk for submucosal invasion continues to be difficult. Early-stage GC typically has a favorable prognosis; nevertheless, submucosal invasion elevates the risk of lymph node metastases and recurrence, requiring more aggressive treatment strategies[13,14]. This highlights the necessity of precisely identifying risk variables linked to submucosal invasion to successfully customize treatment regimens. This investigation involved a thorough review of the risk factors linked to submucosal invasion in patients with early-stage differentiated GC[15,16]. Our findings identified multiple significant clinical, imaging, and endoscopic predictors that are crucial for recognizing patients at elevated risk for submucosal invasion. Comprehending these variables is essential for enhancing management methods in early-stage GC, especially in identifying the most suitable therapeutic approach and augmenting patient outcomes.

Our multivariate analysis revealed a robust correlation between tumor location in the upper two-thirds of the stomach and the probability of submucosal invasion. cancers in this location had a more than fivefold likelihood of invading the submucosa compared to cancers situated in other areas of the stomach. This observation can be elucidated by the unique anatomical and physiological features of the upper stomach, comprising the fundus and body of the stomach. The upper stomach possesses a richer blood supply and a denser muscle layer, perhaps enabling deeper tumor infiltration and fostering invasive characteristics. Furthermore, the upper stomach is frequently less mobile than other gastric areas, which may result in delayed clinical manifestations and subsequent identification, thus increasing the risk of submucosal invasion at the time of detection[17-19]. The tumor's gross morphological characteristics were a significant predictor, as depressed-type tumors demonstrated an almost sixfold elevation in the probability of submucosal invasion relative to other types. Depressed-type tumors are generally marked by a concave morphology, indicating more aggressive behavior and a tendency for deeper tissue infiltration. This physical characteristic may indicate more sophisticated biological processes at the cellular level, including augmented angiogenesis, improved stromal contact, and elevated rates of cellular proliferation and migration. These features collectively enhance the aggressive characteristics of depressed-type cancers and increase their propensity for submucosal invasion[20,21].

Marginal elevation, recognized as a crucial predictor in our analysis, also signifies an elevated risk of submucosal invasion. Tumors with marginal elevation display elevated borders, indicating potential tumor growth and infiltration into adjacent tissues. The existence of marginal elevation may suggest a broader tumor dissemination within the stomach wall, affecting both the mucosal and submucosal layers. This characteristic likely signifies an amalgamation of tumor growth dynamics and local tissue responses, such as desmoplastic reaction, which may further promote submucosal invasion[22,23]. Our research emphasized the efficacy of sophisticated endoscopic imaging techniques, particularly LCI, in forecasting submucosal invasion. A high LCI color difference (≥ 18.1) was substantially correlated with submucosal invasion, highlighting the importance of this imaging technique in improving the identification of subtle mucosal and submucosal irregularities. LCI improves the discernibility of color variations in the stomach mucosa, facilitating superior discrimination between normal and diseased tissues. The notable correlation between LCI color difference and submucosal invasion indicates that this imaging modality may serve as an effective instrument for the early detection of high-risk lesions, thus facilitating more prompt and suitable therapeutic measures[24,25].

The ROC curve analysis confirmed the predictive significance of lesion diameter, WLE color difference, and LCI color difference, with AUC values demonstrating moderate predictive capability for these variables. The chosen cutoff parameters for lesion diameter (21.1 mm), WLE color difference (13.1), and LCI color difference (17.3) were established to optimize sensitivity while preserving adequate specificity. These cutoffs are therapeutically significant since they establish criteria for identifying individuals who may necessitate more aggressive treatment strategies, such as surgical resection instead of only endoscopic intervention. The recognition of these risk variables holds significant clinical ramifications. Patients with tumors in the upper stomach, those with depressed-type morphology, or those with considerable marginal elevation and pronounced LCI color differences should be regarded as at elevated risk for submucosal invasion. These patients may require enhanced surveillance and possibly more aggressive treatment approaches to guarantee total tumor excision and reduce the likelihood of recurrence[26,27].

This study clarifies two methodological points: Endoscopic feature assessment and CT imaging criteria. First, we employed a consensus-based approach involving two senior gastroenterologists to assess endoscopic features. An initial independent review by a blinded gastroenterologist was compared with the original report, and in cases of discrepancy, a second independent review was conducted. Final determinations were made by consensus, ensuring reliability and comprehensive lesion characterization. Second, we focused on straightforward CT indicators, such as gastric wall thickening and lymph node abnormalities, chosen for their reliability and ease of assessment. More complex CT features-such as gastric wall layer disruption, outer wall irregularities, perigastric fat stranding, and extension beyond the gastric wall-were excluded due to their subjective nature and variability. As our primary focus is on endoscopic predictors of submucosal invasion, this approach ensures a more objective analysis. Future studies may benefit from integrating these advanced CT characteristics with endoscopic and pathological data.

One limitation of this study is its retrospective design, which may introduce selection bias and affect the generalizability of the findings. To mitigate this, we have clearly detailed the patient selection process and included all eligible cases within the 4-year study period to ensure a comprehensive dataset and reduce bias. Additionally, although the sample size is sufficient, it may not capture the full range of risk factors for submucosal invasion across diverse populations. Our reliance on imaging and endoscopic techniques, despite their advanced nature, may still miss subtle pathological changes. The absence of Helicobacter pylori status assessment is also noted, and future prospective studies would benefit from evaluating its influence on submucosal invasion. We recommend future research with larger, diverse cohorts, incorporating molecular and genetic profiling, and exploring advanced imaging techniques, including artificial intelligence, to enhance predictive accuracy for early-stage GC and improve clinical management strategies.

Depressed-type lesions, those with marginal elevation, located in the upper two-thirds of the stomach, and those with a significant color difference on LCI could indicate a higher risk of submucosal invasion. These findings suggest that such lesions might warrant more aggressive intervention to potentially prevent disease progression and improve patient outcomes.

We appreciate the cooperation and informed consent provided by the patients and/or their families for this study.

| 1. | Smyth EC, Nilsson M, Grabsch HI, van Grieken NC, Lordick F. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2020;396:635-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1150] [Cited by in RCA: 2805] [Article Influence: 561.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 2. | Douda L, Cyrany J, Tachecí I. [Early gastric cancer]. Vnitr Lek. 2022;68:371-375. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Yang K, Lu L, Liu H, Wang X, Gao Y, Yang L, Li Y, Su M, Jin M, Khan S. A comprehensive update on early gastric cancer: defining terms, etiology, and alarming risk factors. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15:255-273. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yu Z, Liang C, Li R, Gao J, Gao Y, Zhou S, Li P. Risk factors associated with lymph node metastasis in early-stage distal gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2024;48:151-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Janczewski LM, Buchheit J, Jacobs RC, Vitello D, Wells A, Abad J, Bentrem DJ, Chawla A. Utilization and survival outcomes of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for early-stage gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2024;130:249-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Wang X, Zhao J, Shen Z, Fairweather M, Enzinger PC, Sun Y, Wang J. Multidisciplinary Approach in Improving Survival Outcome of Early-Stage Gastric Cancer. J Surg Res. 2020;255:285-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yao K, Nagahama T, Matsui T, Iwashita A. Detection and characterization of early gastric cancer for curative endoscopic submucosal dissection. Dig Endosc. 2013;25 Suppl 1:44-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hisada H, Sakaguchi Y, Oshio K, Mizutani S, Nakagawa H, Sato J, Kubota D, Obata M, Cho R, Nagao S, Miura Y, Mizutani H, Ohki D, Yakabi S, Takahashi Y, Kakushima N, Tsuji Y, Yamamichi N, Fujishiro M. Endoscopic Treatment of Superficial Gastric Cancer: Present Status and Future. Curr Oncol. 2022;29:4678-4688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Dao Q, Chen K, Zhu L, Wang X, Chen M, Wang J, Wang Z. Comparison of the clinical and prognosis risk factors between endoscopic resection and radical gastrectomy for early-stage gastric cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2023;21:147. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Cheng J, Wu X, Yang A, Jiang Q, Yao F, Feng Y, Guo T, Zhou W, Wu D, Yan X, Lai Y, Qian J, Lu X, Fang W. Model to identify early-stage gastric cancers with deep invasion of submucosa based on endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography findings. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:855-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:344-349. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5754] [Cited by in RCA: 9771] [Article Influence: 574.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sano T, Aiko T. New Japanese classifications and treatment guidelines for gastric cancer: revision concepts and major revised points. Gastric Cancer. 2011;14:97-100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 219] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Abe N, Mori T, Takeuchi H, Yoshida T, Ohki A, Ueki H, Yanagida O, Masaki T, Sugiyama M, Atomi Y. Laparoscopic lymph node dissection after endoscopic submucosal dissection: a novel and minimally invasive approach to treating early-stage gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2005;190:496-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wen J, Linghu EQ, Yang YS, Liu QS, Yang J, Lu ZS. Associated risk factor analysis for positive resection margins after endoscopic submucosal dissection in early-stage gastric cancer. J BUON. 2015;20:421-427. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Tanabe S, Koizumi W, Mitomi H, Nakai H, Murakami S, Nagaba S, Kida M, Oida M, Saigenji K. Clinical outcome of endoscopic aspiration mucosectomy for early stage gastric cancer. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:708-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Rong L, Cai Y, Nian W, Wang X, Liang J, He Y, Zhang J. [Efficacy comparison between surgical resection and endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer in a domestic single center]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2018;21:190-195. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Gotoda T, Yamamoto H, Soetikno RM. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:929-942. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 485] [Cited by in RCA: 506] [Article Influence: 26.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Conti CB, Agnesi S, Scaravaglio M, Masseria P, Dinelli ME, Oldani M, Uggeri F. Early Gastric Cancer: Update on Prevention, Diagnosis and Treatment. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 35.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Jin CQ, Zhao J, Ding XY, Yu LL, Ye GL, Zhu XJ, Shen JW, Yang Y, Jin B, Zhang CL, Lv B. Clinical outcomes and risk factors of non-curative endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer: a retrospective multicenter study in Zhejiang, China. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1225702. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yamada T, Sugiyama H, Ochi D, Akutsu D, Suzuki H, Narasaka T, Moriwaki T, Endo S, Kaneko T, Satomi K, Ikezawa K, Mizokami Y, Hyodo I. Risk factors for submucosal and lymphovascular invasion in gastric cancer looking indicative for endoscopic submucosal dissection. Gastric Cancer. 2014;17:692-696. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kumazu Y, Hayashi T, Yoshikawa T, Yamada T, Hara K, Shimoda Y, Nakazono M, Nagasawa S, Shiozawa M, Morinaga S, Rino Y, Masuda M, Ogata T, Oshima T. Risk factors analysis and stratification for microscopically positive resection margin in gastric cancer patients. BMC Surg. 2020;20:95. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Oh YJ, Kim DH, Han WH, Eom BW, Kim YI, Yoon HM, Lee JY, Kim CG, Kook MC, Choi IJ, Kim YW, Ryu KW. Risk factors for lymph node metastasis in early gastric cancer without lymphatic invasion after endoscopic submucosal dissection. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2021;47:3059-3063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kim DH, Yun HY, Ryu DH, Han HS, Han JH, Kim KB, Choi H, Lee TG. Clinical significance of the number of retrieved lymph nodes in early gastric cancer with submucosal invasion. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101:e31721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Lee SH, Kim MC, Jeon SW, Lee KN, Park JJ, Hong SJ. Risk Factors and Clinical Outcomes of Non-Curative Resection in Patients with Early Gastric Cancer Treated with Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection: A Retrospective Multicenter Study in Korea. Clin Endosc. 2020;53:196-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Liu JM, Liang L, Zhang JX, Rong L, Zhang ZY, Wu Y, Zhao XD, Li T. [Pathological evaluation of endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer and precancerous lesion in 411 cases]. Beijing Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2023;55:299-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Miyahara K, Hatta W, Nakagawa M, Oyama T, Kawata N, Takahashi A, Yoshifuku Y, Hoteya S, Hirano M, Esaki M, Matsuda M, Ohnita K, Shimoda R, Yoshida M, Dohi O, Takada J, Tanaka K, Yamada S, Tsuji T, Ito H, Aoyagi H, Shimosegawa T. The Role of an Undifferentiated Component in Submucosal Invasion and Submucosal Invasion Depth After Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection for Early Gastric Cancer. Digestion. 2018;98:161-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lan Z, Hu H, Mandip R, Zhu W, Guo W, Wen J, Xie F, Qiao W, Venkata A, Huang Y, Liu S, Li Y. Linear-array endoscopic ultrasound improves the accuracy of preoperative submucosal invasion prediction in suspected early gastric cancer compared with radial endoscopic ultrasound: A prospective cohort study. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:118-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |