Published online Nov 7, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i41.4484

Revised: September 26, 2024

Accepted: October 12, 2024

Published online: November 7, 2024

Processing time: 100 Days and 19.9 Hours

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs), including Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis, are chronic inflammatory conditions of the gastrointestinal tract that necessitate timely diagnosis to prevent complications and improve patient outcomes. Despite advancements in medical knowledge and diagnostic tech

Core Tip: This editorial highlight the persistent issue of diagnostic delays in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), with a focus on the differences between Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). In CD, symptoms such as diarrhea and skin lesions are associated with longer diagnostic times, whereas in UC, fever shortens the diagnostic time, but fatigue and a positive family history prolong it. These variations reflect the complex nature of IBD diagnosis. To address these challenges, the editorial advocates for improved physician education, public awareness initiatives, interdisciplinary teamwork, and the use of noninvasive screening tools to enhance early diagnosis and patient outcomes.

- Citation: Zhang SY, Lin Y. Addressing diagnostic delays in inflammatory bowel diseases in Germany. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(41): 4484-4489

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i41/4484.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i41.4484

Ulcerative colitis (UC) and Crohn’s disease (CD) are the predominant subtypes of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) frequently encountered in clinical settings. The complexity of diagnosing IBD arises from its diverse and often subtle clinical manifestations, coupled with the limited diagnostic precision of current biomarker tests. As a result, substantial delays frequently occur between the onset of symptoms and the establishment of an accurate diagnosis. However, prompt diagnosis and treatment of these patients is critical. The study by Blüthner et al[1], published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, sought to systematically evaluate the risk factors contributing to delayed diagnosis in a German cohort of IBD patients, with the goal of improving overall disease management.

The study by Blüthner et al[1], published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology, is a prospective, cross-sectional, que

The questionnaire administered consisted of 16 items aimed at exploring demographic and disease-specific factors that could potentially influence diagnostic delays, either directly or indirectly. Furthermore, three important time intervals were assessed via the questionnaires: The duration from symptom onset to initial physician contact, the period from first contact to diagnosis, and the total diagnostic time. This research design allowed for a comprehensive assessment of diagnostic delays in IBD, particularly focusing on the disparities between CD and UC. The use of questionnaires enabled the collection of detailed patient histories and symptomatology, providing valuable insights into the factors contributing to prolonged diagnostic times.

This underscores the challenges in diagnosing CD compared with UC, particularly the impact of nonspecific symptoms and the need for specific diagnostic tools. Factors such as older age at diagnosis and complicated disease presentation exacerbate this delay[2]. The nonspecific nature of CD symptoms, which often overlap with other gastrointestinal disorders, further complicates and prolongs the diagnostic process. Symptoms such as abdominal pain, altered bowel habits, constipation, or diarrhea are common in patients with CD and can lead to misdiagnosis as other gastrointestinal disorders, contributing to significant diagnostic delays[3].

This study identified several risk factors associated with prolonged diagnostic times. These distinct risk factors contribute to diagnostic delays in both CD and UC patients. Specific symptoms, such as diarrhea and skin lesions in CD patients and fever in UC patients, are key factors influencing diagnostic time. Other factors, such as fatigue and family history, complicate the process. This emphasizes the complexity and variation in diagnostic pathways between CD and UC, as well as the critical role that nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, play in influencing the diagnostic process in IBD. Notably, in previous research conducted by Gong et al[4], factors like disease activity, depression, anxiety, anemia, and IBD-related surgeries were found to significantly elevate the risk of fatigue in patients with IBD, with a prevalence of fatigue of 60.77%. These findings emphasize that fatigue is a critical symptom influencing diagnostic delays in both CD and UC, adding to the overall complexity of timely IBD diagnosis.

The study highlighted that readily available diagnostic tools, such as colonoscopy and gastroscopy, could significantly reduce physician diagnostic time. In particular, the performance of diagnostic gastroscopy was associated with a shorter diagnostic time for CD patients. This suggests that improving access to and utilization of these diagnostic procedures could be a critical step in reducing delays[5]. Rapid and accurate diagnostic tools enable physicians to differentiate IBD from other gastrointestinal disorders more efficiently, facilitating timely diagnosis and intervention[6]. Additionally, the use of noninvasive biomarkers, such as fecal calprotectin, can aid in the early identification of inflammatory processes, further streamlining the diagnostic pathway and reducing the overall time to diagnosis[7]. Enhancing the availability and application of these diagnostic methods in clinical practice is essential for minimizing diagnostic delays and improving patient outcomes.

Addressing diagnostic delays in IBD requires a multifaceted approach. Enhanced education and training for healthcare providers can improve early recognition of IBD symptoms and facilitate timely referrals. Public awareness campaigns can encourage patients to seek medical advice earlier, whereas interdisciplinary collaboration between primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, and other specialists can streamline the diagnostic process[8]. The implementation of effective screening tools, such as questionnaires, and noninvasive biomarkers, such as fecal calprotectin, in primary care settings can aid in the early identification of potential IBD cases.

The original text states: "HRs exceeding unity (HR > 1) represented a better chance for early diagnosis". In the context of statistical analysis, particularly when discussing HRs, using the term "higher" is more precise and appropriate than "better". The term "higher" accurately reflects the increase in the hazard rate or the probability of the event occurring sooner. Thus, the sentence may be revised for clarity and precision.

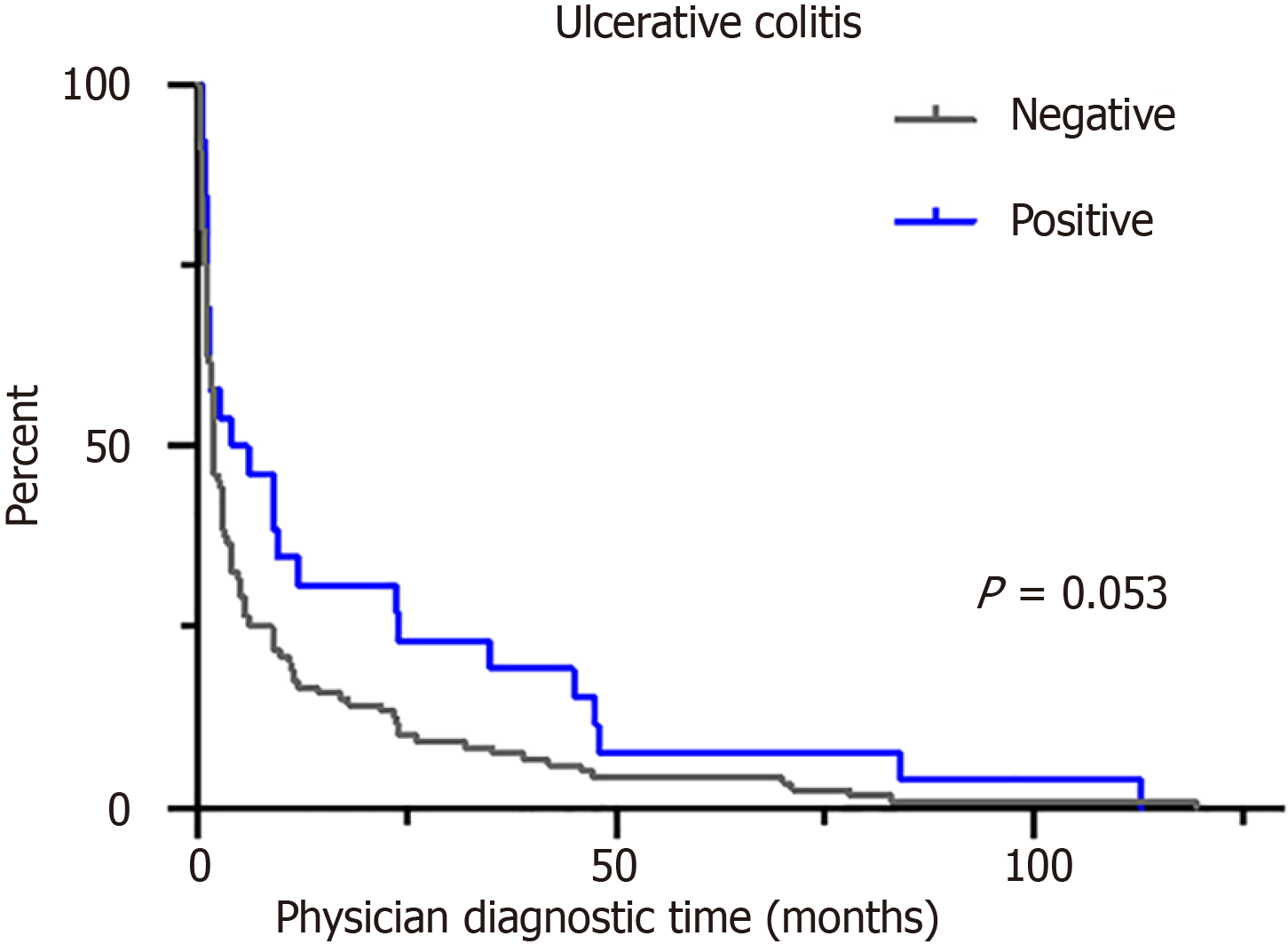

The legend for original figure 3D (Figure 1) originally stated that a positive family history delayed physician diagnostic time in UC patients. However, the figure indicates a P value of 0.053, which does not meet the conventional threshold for statistical significance (P < 0.05). Therefore, the legend should be revised to accurately reflect the statistical results. Revised legend: “Positive family history tends toward delaying physician diagnostic time in UC patients (P = 0.053)”. This adjustment ensures that the legend is consistent with the data presented, providing a clearer interpretation of the study's findings.

In these tables, the column name is labeled “odds ratio”, but the legend at the bottom of the table refers to “HR”. This inconsistency needs correction to maintain clarity and accuracy. If the analysis presented hazard ratios, all mentions should uniformly reflect "HR".

In the last sentence of the fourth paragraph in the Discussion Section, there is a typographical error. The reference to gastroscopy in relation to decreased physician diagnostic time for CD patients should be found in table 4 (Table 2), not table 3 (Table 1).

The term “positive family history” specifically refers to a family history of IBD, including CD and UC. Providing specific details will enhance the clarity of the findings.

Clearly, define what constitutes a diagnostic delay. The duration that is considered a delay in diagnosis is specified to ensure consistency and understanding in the interpretation of the study results.

Explain how different diagnostic times affect prognosis and treatment outcomes. Detail whether different diagnostic times lead to variations in treatment approaches and patient prognoses.

In the study design assessment paragraph, the total percentage of patients in the 4 hospitals exceeded 100% (42.3% + 28.4% + 26.0% + 18% = 114.7%). Reconcile the data to ensure that the data are correct.

The evaluation periods indicated by the authors included 2020, 2021, and 2022, which coincide with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic. It is vital to emphasize in the introduction how SARS-CoV-2 infection has been described as a risk factor for poor therapeutic adherence[9] and to provide a preface to explain studies that have already introduced this topic[10], as SARS-CoV-2 infection may lead to diagnostic delays in IBD. Questions related to SARS-CoV-2 infection could be added to the questionnaire.

To improve the diagnostic timelines for IBD, a multifaceted approach is needed. This includes: Enhanced education and training: Continuous medical education programs for general practitioners focusing on the early signs and symptoms of IBD can facilitate timely referrals[11].

Public awareness campaigns: Increasing public awareness of IBD and its symptoms can empower patients to seek medical advice sooner

Interdisciplinary collaboration: Strengthening the collaboration between primary care physicians, gastroenterologists, and other specialists can streamline the diagnostic process[12].

Research and policy implementation: Further research into diagnostic delays and the development of national guidelines for the early diagnosis and management of IBD can help standardize care and reduce delays.

The study by Blüthner et al[1]. underscores the critical need to address diagnostic delays in IBD, particularly in CD. By identifying key risk factors and advocating for improved awareness, education, and early intervention strategies, we can enhance the diagnostic process, leading to better patient outcomes and reduced disease burden.

| 1. | Blüthner E, Dehe A, Büning C, Siegmund B, Prager M, Maul J, Krannich A, Preiß J, Wiedenmann B, Rieder F, Khedraki R, Tacke F, Sturm A, Schirbel A. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel diseases in a German population. World J Gastroenterol. 2024;30:3465-3478. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (9)] |

| 2. | Cantoro L, Di Sabatino A, Papi C, Margagnoni G, Ardizzone S, Giuffrida P, Giannarelli D, Massari A, Monterubbianesi R, Lenti MV, Corazza GR, Kohn A. The Time Course of Diagnostic Delay in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Over the Last Sixty Years: An Italian Multicentre Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:975-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | AWARE-IBD Diagnostic Delay Working Group. Sources of diagnostic delay for people with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: Qualitative research study. PLoS One. 2024;19:e0301672. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Gong SS, Fan YH, Lv B, Zhang MQ, Xu Y, Zhao J. Fatigue in patients with inflammatory bowel disease in Eastern China. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:1076-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Núñez F P, Krugliak Cleveland N, Quera R, Rubin DT. Evolving role of endoscopy in inflammatory bowel disease: Going beyond diagnosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:2521-2530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Brodersen JB, Knudsen T, Kjeldsen J, Juel MA, Rafaelsen SR, Jensen MD. Diagnostic accuracy of pan-enteric capsule endoscopy and magnetic resonance enterocolonography in suspected Crohn's disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10:973-982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wright E. Non-invasive biomarkers as treatment targets: What do we all need to know? J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;36 Suppl 1:12-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cross E, Saunders B, Farmer AD, Prior JA. Diagnostic delay in adult inflammatory bowel disease: A systematic review. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023;42:40-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pellegrino R, Pellino G, Selvaggi F, Federico A, Romano M, Gravina AG. Therapeutic adherence recorded in the outpatient follow-up of inflammatory bowel diseases in a referral center: Damages of COVID-19. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54:1449-1451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 10. | Manuel AR, Magalhães T, Granado MC, Espinheira MDC, Trindade E. Evolution of diagnostic delays in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Arq Gastroenterol. 2023;60:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Reed S, Dave S, Bugwadia A. Best practices to support inflammatory bowel disease patients in higher education and the workplace: A clinician’s guide. Health Care Transit. 2023;1:100017. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Agrawal M, Spencer EA, Colombel JF, Ungaro RC. Approach to the Management of Recently Diagnosed Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients: A User's Guide for Adult and Pediatric Gastroenterologists. Gastroenterology. 2021;161:47-65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 37.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |