TO THE EDITOR

We read with great interest an article by Japanese scholars examining the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib treatment in Asian patients with ulcerative colitis (UC)[1]. This study included 111 UC patients, with a follow-up period exceeding one year, making it one of the largest real-world studies on tofacitinib treatment for UC in Asia. The main findings of the study were as follows: (1) The clinical remission rate was 50.5% at 8 weeks and 43.5% at 48 weeks, and the overall cumulative remission rate was 61.7%; (2) A history of previous treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) agents did not affect the efficacy of tofacitinib; (3) Patients who achieved clinical remission at 8 weeks had a significantly higher continuation rate of tofacitinib compared to those who did not reach remission; (4) 45.7% of patients relapsed after reducing or stopping tofacitinib, but most were able to regain remission after dose escalation; and (5) 6 patients (5.4%) developed shingles, all occurring after achieving remission with tofacitinib treatment. We fully appreciate the reference this clinical study provides for the future clinical application of tofacitinib. We believe that this research lays a certain foundation for the broader application of tofacitinib.

UC is a refractory chronic inflammatory disease of the intestinal mucosa. The occurrence of UC is the result of a combination of factors and its pathogenesis is complex and intricate. To date, the reported pathogenesis includes: (1) Genetic regulation: Gene mutations, deletions, overlaps, risk loci, etc. can all cause genetic susceptibility to UC; (2) Lifestyle regulation: Poor diet, smoking and the use of antibiotics can increase the risk of UC; (3) Immune regulation: Dysregulation or abnormal immune response is an important factor in the pathogenesis of UC, including an increase in antibodies, cytokines and pro-inflammatory mediators released by effector cells such as macrophages, neutrophils, T lymphocytes, B lymphocytes, mast cells and natural killer cells, which stimulate the proliferation of antigen-specific effector cells and trigger the adaptive immune system, leading to local and systemic inflammation. In addition, a Th1/Th2 imbalance can suppress the immune response; (4) Regulation of the gut microbiota: Imbalances in the gut microbiota caused by various factors mentioned above can lead to UC; and (5) Regulation of signaling pathways: NF-kB can affect hypoxia-inducible factor-1a, cyclooxygenase-2, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, TNF-α, etc., inducing and regulating the development of immune and inflammatory responses through various pathways[2-6]. The PI3K/Akt pathway can indirectly activate NF-κB, while toll-like receptor 4 can activate the PI3K/Akt pathway, synergistically promoting the expression and secretion of inflammatory factors, leading to colonic mucosal damage[7,8]. The JAK/STAT pathway mediates the expression of cytokines required by intestinal immune and stromal cells to maintain homeostasis, and its abnormalities can lead to abnormal T-cell differentiation and defects in T-cell regulatory activity, another important mechanism in the pathogenesis of UC[9,10]. The discovery of these pathological mechanisms provides targets and clues for the treatment of UC.

At present, the treatment of UC still focuses on inducing and maintaining symptom relief, reducing the risk of complications, and improving quality of life. Usually, the appropriate treatment method is selected by assessing the severity of the disease. Based on the comprehensive reference to clinical diagnosis and treatment guidelines, for mild to moderate UC, the recommended first-line treatment options for induction and maintenance of remission are various formulations of mesalazine compounds, which belong to the 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) class[11]. The PANCCO clinical practice guidelines explicitly recommend that budesonide is an option when 5-ASA treatment fails and before the use of corticosteroid[12]. For moderate to severe UC, corticosteroids are first-line induction therapy drugs. In addition, immunosuppressants (thiopurine), biologics (such as anti-TNF, anti-integrin, anti-IL-12, and anti-IL-23 antibodies), and small molecule (such as JAK inhibitors and sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators) targeted drugs can be used for maintenance therapy of UC[11]. The PANCCO guidelines recommend using infliximab, adalimumab, vedolizumab, ustekinumab, and tofacitinib as first-line treatments[12]. For patients with acute and severe UC, it is recommended that they are hospitalized for intensive treatment, using medications such as corticosteroids, anti-TNF, and cyclosporine[11]. However, the efficacy of drug therapy is limited. In the case of drug therapy failure, surgical treatment is necessary. Research shows that 20% of patients require colon resection on their first admission, which increases to 40% on their second admission[11].

Inevitably, these treatment methods have various limitations. For example, 5-ASA drugs can cause gastrointestinal adverse reactions such as decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, as well as side effects such as granulocytopenia, autoimmune hemolysis, and nephrotoxicity. Long-term use of corticosteroid drugs can lead to serious adverse reactions such as peptic ulcers, Cushing's syndrome, growth inhibition, muscle weakness, osteoporosis, etc. When the dosage is rapidly reduced, it can cause early recurrence of UC, so long-term use is not recommended. Immunosuppressants have cyto-toxicity and long-term use can cause serious adverse reactions such as bone marrow hematopoietic dysfunction and liver and kidney function damage. Anti-TNF drugs are expensive and may increase the risk of infection. Anti-integrins are also expensive. Colonostomy can cure the disease, but it requires an intestinal stoma. Colonic preservation surgery carries a risk of recurrence. Thus, new, more effective and safer therapies are needed in the future.

As mentioned earlier, anti-TNF-α antibodies are one of the main treatment methods for UC. When UC occurs, TNF-α is produced by a subpopulation of intestinal immune cells, mainly inducing pro-inflammatory factors, activating macrophages and T cells, leading to epithelial cell apoptosis, cell damage, and intestinal mucosal destruction, and participating in the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity[4,11]. Therefore, from the perspective of immune regulation, TNF antibodies can effectively inhibit the progression of UC. However, clinical practice has shown that up to 40% of patients do not respond to TNF drugs, making the identification of alternative therapeutic targets a priority. If anti-TNF therapy fails, anti-IL-12 and anti-IL-23 antibodies such as ustekinumab and the JAK inhibitor tofacitinib can provide the best results[13,14].

The rise of JAK inhibitors in recent years has brought new prospects to the treatment of UC. The non-selective all JAK inhibitor tofacitinib, as well as the selective JAK1 or JAK3 inhibitors fagatinib and upadacitinib, have been approved as monotherapy for UC in Japan, and are suitable for patients with insufficient response or intolerance to biologics[15-17]. Tofacitinib, as the first approved JAK inhibitor, has several potential advantages as proposed in a recent meta-analysis, such as oral administration, high efficacy, rapid action, rapid clearance, insensitivity to drug loss associated with hypoalbuminemia, lack of immunogenicity, and treatment efficacy not affected by previous biological agent reactions[18]. However, high-quality evidence-based data are still needed to evaluate its effectiveness and safety in treating UC.

This clinical trial could provide high-quality evidence for the clinical use of tofacitinib in the following four aspects: (1) Reasonableness of the study design: This research uses a retrospective single-center observational design, including a significant number of UC patients, with a follow-up period of over a year. This allows for a comprehensive assessment of the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in clinical practice. Compared to clinical trials, real-world studies better represent treatment effects in actual clinical settings, providing more valuable evidence for clinical decision-making. The inclusion and exclusion criteria for this study are clearly defined. Certain special cases, such as patients with unclassified inflammatory bowel disease, those who underwent colectomy, and patients with follow-up time of less than 8 weeks, were excluded, which helps in accurately assessing the efficacy of tofacitinib; (2) Reasonableness of the research methods: This study employs standard clinical efficacy evaluation indicators, such as clinical remission rate, duration of clinical remission, and surgical immunization rate, which are widely used in UC clinical studies and have good comparability. Additionally, the study also evaluates endoscopic efficacy. Although endoscopic examination is not necessary for all the cases, and there are many missing endoscopic data, it can still reflect the overall endoscopic efficacy of tofacitinib treatment. The study also analyzed the recurrence rate after reducing or discontinuing tofacitinib, as well as the efficacy of increasing the dose again after recurrence. The exploration of these clinical issues is of great significance for optimizing tofacitinib treatment strategies; (3) Reasonableness of the statistical analysis: This study employed appropriate statistical methods, such as the Mann-Whitney U test, Fisher's exact test, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis, which provide a comprehensive assessment of various indicators of tofacitinib treatment. Additionally, the study explored the correlation between baseline characteristics and tofacitinib efficacy, using logistic regression to identify independent factors that predict efficacy at 8 and 48 weeks, which helps to better forecast the effectiveness of tofacitinib treatment; and (4) Validity of the results: The main findings of this study are generally consistent with previous clinical trials and real-world studies regarding tofacitinib treatment for UC, indicating good scientific validity. For instance, the clinical remission rate at 8 weeks in this study was 50.5%, aligning with previously reported rates that ranged from 19% to 50%. Furthermore, the study found that a history of prior treatment with anti-TNF-α agents did not affect tofacitinib efficacy, which is consistent with past research. It was also noted that patients with lower baseline Mayo scores were more likely to achieve remission with tofacitinib treatment, suggesting that tofacitinib may be more suitable for patients with lower disease activity.

On the basis of rational and scientific research design, this study has good clinical significance and application value, which can provide effective reference for the promotion and application of tofacitinib in the following five aspects: (1) Providing valuable real-world evidence for tofacitinib therapy in Asian UC patients. Currently, clinical trial data on tofacitinib therapy for UC are mainly from Western populations, while there are certain differences in genetic background and disease phenotype among Asian populations. Compared to previous clinical trials, this study provides long-term real-world evidence for tofacitinib therapy in Asian UC patients, and provides an important reference for clinical doctors to use tofacitinib therapy for UC in the Asian region; (2) Providing a basis for optimizing tofacitinib treatment strategies. This study not only evaluated the short-term and long-term efficacy of tofacitinib, but also investigated the recurrence rate after tofacitinib reduction or discontinuation, as well as the efficacy of increasing the dose again after recurrence. These results have important guiding significance for formulating the optimal timing and dosage strategy for tofacitinib treatment. For example, studies have found that most patients experience relapse after reducing or discontinuing tofacitinib, but most of these patients can regain remission after increasing the dose again. This suggests that caution should be exercised when reducing or discontinuing tofacitinib in UC patients after remission to reduce the risk of relapse; (3) Providing a basis for predicting the efficacy of tofacitinib therapy. This study found that patients with lower baseline Mayo scores were more likely to achieve remission following tofacitinib therapy, which provides a reference for clinical doctors to predict the efficacy of tofacitinib therapy. This helps doctors choose treatment strategies rationally and improve treatment effectiveness; (4) Providing a reference for the timing of tofacitinib in the treatment of UC. This study found that a history of using anti TNF-α preparations did not affect the efficacy of tofacitinib, indicating that tofacitinib may be a new treatment option, particularly suitable for UC patients who have failed in the previous biologic treatments. In addition, the study also revealed that tofacitinib was more suitable for UC patients with lower disease activity, which provides a reference for the timing of tofacitinib in UC treatment; and (5) Providing a basis for safety monitoring. The drug dosage used in this study was 10 mg twice a day for most patients, and 5 mg twice a day for a small number of patients, with an observation period of 80.5 patient years. During the follow-up period, 58 adverse events occurred, with 7 patients (6.3%) stopping tofacitinib treatment due to adverse events, and 38 patients (34.2%) experiencing at least one adverse event. Specific adverse reactions included hypercholesterolemia in 17 (15.3%) cases, fever, headache, lower limb edema, general fatigue, sore throat, palpitations, joint pain, general pain, dizziness, drowsiness, deep vein thrombosis, developmental disorders, and elevated creatine kinase in 3 cases (2.7%), and abnormal liver function tests in 1 case (0.9%). In addition, in terms of infectious diseases, there were 6 cases of herpes zoster (5.4%), 5 cases of upper respiratory tract infection (4.5%), 3 cases of influenza (2.7%), and 1 case of bronchitis, herpes labialis, norovirus enteritis, Clostridium difficile colitis, and folliculitis (0.9%), respectively. This suggests that clinical doctors need to closely monitor the risk of herpes zoster in patients treated with tofacitinib.

Although this clinical study has clinical significance and application value, it has some limitations that may affect the quality of its support as clinical evidences for tofacitinib: (1) Single center retrospective study design: This study adopts a single center retrospective study design, which has certain selection bias. Future multicenter prospective studies are needed to further validate the reliability and broad applicability of the research findings; (2) Some patients did not undergo endoscopic examination: Due to the fact that some patients did not undergo endoscopic examination, the study only evaluated the efficacy based on clinical symptoms, which may have certain inaccuracies. Ideally, the efficacy of tofacitinib should be comprehensively evaluated by combining clinical symptoms and endoscopic examination findings; (3) Relatively short observation time: Although the median observation period of this clinical study exceeded one year, which is longer than previous clinical studies, it is still relatively short. Long-term follow-up is required in the future to evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib; (4) Lack of a control group: This study is a single arm observational study and lacks a control group. In the future, comparative studies should be conducted between tofacitinib and other treatment methods to better evaluate the relative efficacy of tofacitinib; and (5) No in-depth exploration of adverse reactions: This study focused on the efficacy of tofacitinib, and the analysis of adverse reactions was insufficient. In the future, more attention should be paid to the safety of tofacitinib in UC patients of different races and countries, especially to the occurrence and management strategies of adverse reactions such as herpes zoster.

In fact, researchers have conducted multiple randomized controlled clinical trials on various drugs for the treatment of UC, including anti TNF-α monoclonal antibody, azathioprine, JAK inhibitors, anti-trafficking agents, IL-23 inhibitors, sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor modulators, phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, toll-like receptor 9 agonists, and the potential “first-in-class” UC drug obefazimod (ABX464), etc.[19-27]. There are significant differences in the mechanism of action, use, dosage, administration route, effectiveness in randomized trials, and adverse reactions among drugs of different categories[13,14]. For example, for azathioprine drugs such as nitrogen mustard and mercaptopurine, they maintain remission of hormone dependent UC by inhibiting purine synthesis or are used in combination with TNF inhibitors to reduce immunogenicity. In randomized trials, they have shown higher clinical and endoscopic remission rates in hormone dependent UC patients and can reduce hormone use compared to 5-ASA[28]. However, their adverse reactions are serious problems, including leukopenia, hepatotoxicity, gastrointestinal intolerance and pancreatitis, increased risk of lymphoma and non melanoma skin cancer, etc. Currently, tofacitinib is used as a last resort before colon resection, or as a second-line drug in patients with failed biological therapy after methylprednisolone failure, or as a third line drug after consecutive failures of methylprednisolone and infliximab/cyclosporine[18]. However, there are certain differences in the clinical dosage and course of tofacitinib treatment. The maximum dose used in this clinical trial is 10 mg twice a day. Previous case-control studies have found that a dosage of 10 mg three times a day could significantly protect against colon resection, but larger sample sizes of clinical data and endoscopic examination results are still needed to support this result[29]. In all studies included in a clinical meta-analysis, 22 adverse events occurred in 148 patients, of which 7 were due to discontinuation of tofacitinib, and the vast majority were also related to infectious complications, besides herpes zoster[18]. Upadacitinib, which has a similar mechanism of action to tofacitinib, is a specific inhibitor of JAK1, with a selectivity for JAK1 that is 74 times than that of JAK2. Upadacitinib treatment for UC can achieve a certain degree of clinical and endoscopic remission[30], but it also causes adverse reactions[31]. It is advised that upadacitinib should be used with caution and in low doses in the elderly, and should be avoided by pregnant/Lactating women. Currently, it has not been approved for use in children/adolescents. It can be seen that although there are currently many drugs theoretically available for treating UC, the clinical trials that have been conducted have various limitations and further in-depth research is needed to provide more accurate references for clinical applications.

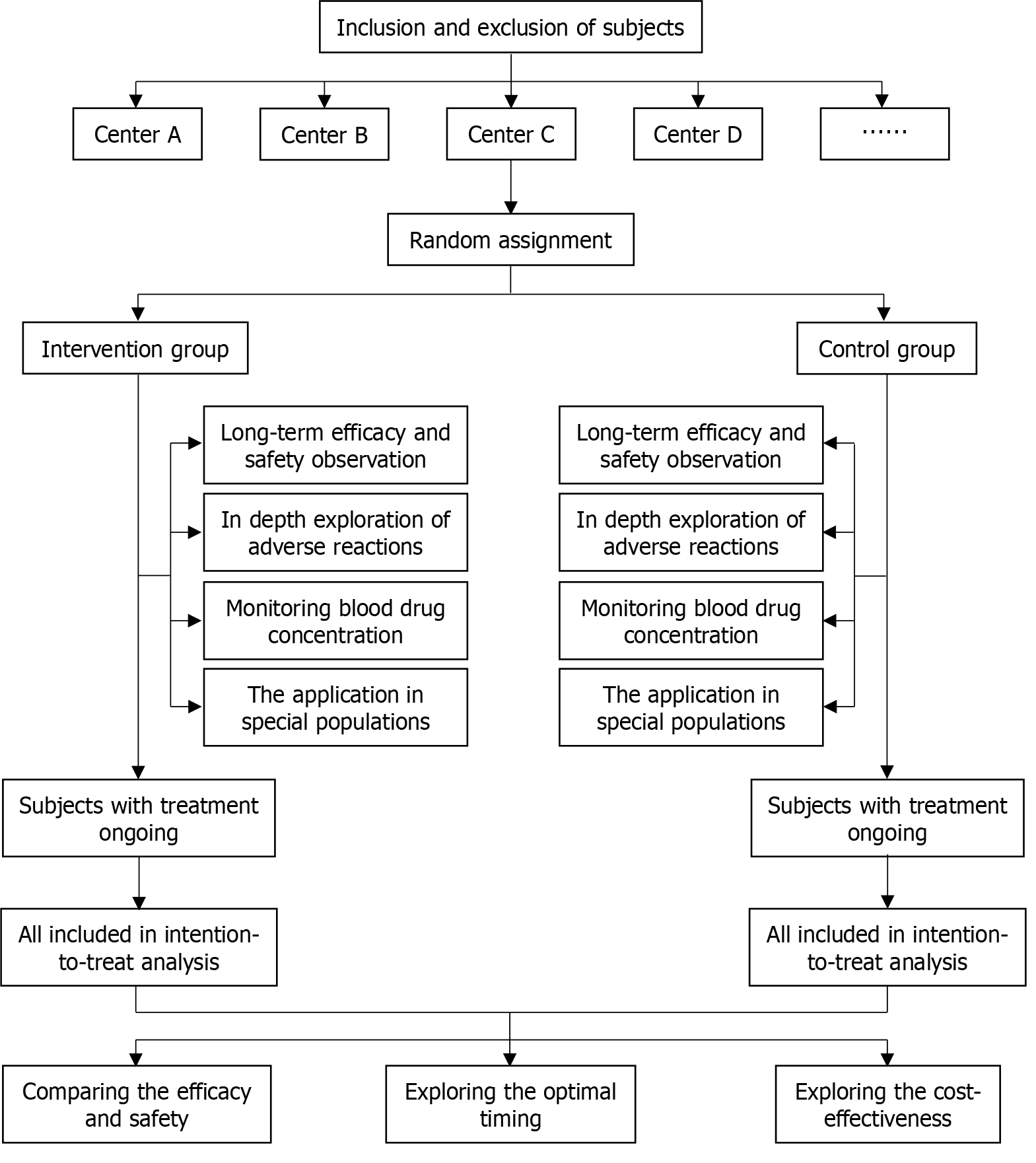

With regard to tofacitinib, a large amount of clinical practice and research data are needed to support how to choose appropriate intervention timing based on the development stage of UC, how to develop a reasonable treatment strategies (including dosage, intervention cycle, etc.), and how to obtain the maximum patient benefit with the lowest economic consumption, or the advantages compared to similar drugs such as upadacitinib. The suggested flowchart in future clinical studies is shown in Figure 1, and the following designs are expected: (1) Conducting large-scale, multicenter prospective studies: Given the limitations of this study, large-scale, multicenter prospective studies should be conducted in the future to further validate the results of this study and explore the optimal application strategy of tofacitinib in Asian UC patients, which can better control bias, and improve the reliability and wide applicability of the results. In addition, considering that race may have a significant impact on the phenotype of UC, the population pharmacokinetics, and adverse reactions of tofacitinib, in large-scale multicenter clinical trials should be conducted across races and regions to fully evaluate the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, instead of being limited to UC patients in Asia; (2) Evaluating the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib: The observation period of this study is relatively short, and more long-term follow-up is needed in the future to comprehensively evaluate the long-term efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in UC patients of different ethnicities. This will provide a more reliable decision-making basis for clinical doctors; (3) In depth exploration of the safety of tofacitinib: Although this study mentioned the adverse reactions of tofacitinib, the analysis is relatively simple. In the future, more attention should be paid to the safety of tofacitinib in induction therapy and maintenance therapy for UC patients of different ethnicities, especially in conducting in-depth research on the occurrence of adverse reactions such as herpes zoster, risk factors, and prevention/management strategies. This will help clinical doctors better identify and manage adverse reactions during the treatment of tofacitinib; (4) Monitoring blood drug concentration: In future clinical studies, the various effects of different drug doses on adverse reactions should be taken seriously. In order to accurately evaluate the correlation between drug dosage and adverse reactions, or effectively prevent and control adverse reactions, blood drug concentration monitoring should be designed in clinical trial protocols when necessary; (5) Exploring the application of tofacitinib in special populations: In addition to general UC patients, future research should also focus on the application of tofacitinib in special populations such as the elderly, pregnant/Lactating women, children/adolescents, and patients with other comorbidities. This will help guide clinical doctors in developing personalized treatment strategies for different types of UC patients; (6) Comparing the efficacy and safety of tofacitinib with other treatment methods: Future research should focus on comparing tofacitinib with other biologics or small molecule targeted drugs (including its analog upadacitinib) to clarify its timing in the treatment of UC. This will help clinical doctors choose the most suitable treatment strategy based on the specific situation of the patient; (7) Exploring the optimal timing of tofacitinib in the treatment of UC: With the continuous deep understanding of the pathological mechanism of UC, future research should focus on the optimal timing of tofacitinib in the treatment of UC and confirm the optimal timing of administration. This will help clinical doctors achieve personalized treatment based on the specific situation of patients; and (8) Exploring the cost-effectiveness of tofacitinib: Inflammatory bowel disease is a chronic disease with high treatment costs. It is necessary to strengthen pharmacoeconomic research to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of tofacitinib compared to other therapeutic drugs in the treatment of UC, in a rapidly changing treatment market with an increasing number of biosimilar drugs.

Figure 1

The flowchart of large-scale, multicenter and prospective clinical studies.

In summary, this study provides valuable practical experience for clinical doctors and is of great significance for optimizing the application of tofacitinib in Asian UC patients. In the future, larger scale and longer-term prospective studies are needed to further validate and improve clinical practice in this field. In addition, attention should be paid to the application of tofacitinib in special populations, as well as its comparison and cost-effectiveness with other treatment methods, in order to provide more personalized and economical treatment options for UC patients.