Published online Jan 28, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i4.346

Peer-review started: October 3, 2023

First decision: December 6, 2023

Revised: December 17, 2023

Accepted: January 9, 2024

Article in press: January 9, 2024

Published online: January 28, 2024

Processing time: 115 Days and 1.7 Hours

Extreme heat exposure is a growing health problem, and the effects of heat on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract is unknown. This study aimed to assess the incidence of GI symptoms associated with heatstroke and its impact on outcomes.

To assess the incidence of GI symptoms associated with heatstroke and its impact on outcomes.

Patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) due to heatstroke were included from 83 centres. Patient history, laboratory results, and clinically relevant outcomes were recorded at ICU admission and daily until up to day 15, ICU discharge, or death. GI symptoms, including nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, flatulence, and bloody stools, were recorded. The characteristics of patients with heatstroke concomitant with GI symptoms were described. Multivariable regression analyses were performed to determine significant predictors of GI symptoms.

A total of 713 patients were included in the final analysis, of whom 132 (18.5%) patients had at least one GI symptom during their ICU stay, while 26 (3.6%) suffered from more than one symptom. Patients with GI symptoms had a significantly higher ICU stay compared with those without. The mortality of patients who had two or more GI symptoms simultaneously was significantly higher than that in those with one GI symptom. Multivariable logistic regression analysis revealed that older patients with a lower GCS score on admission were more likely to experience GI symptoms.

The GI manifestations of heatstroke are common and appear to impact clinically relevant hospitalization outcomes.

Core Tip: This study aimed to assess the incidence of gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms associated with heatstroke and its impact on outcomes. This was a retrospective, multi-center, observational cohort study that involved patients admitted to 83 intensive care unit located in 16 cities in the Sichuan Province, China between June 1 and October 31, 2022. Results showed older heatstroke patients with a lower Glasgow coma scale score on admission were more likely to experience GI symptoms, which had statistical difference. Clinicians should pay attention to the time at which heatstroke patients started manifesting GI symptoms, as well as the duration of said symptoms, to ensure that patients are timely treated with the proper enteral therapy and have the best prognosis possible.

- Citation: Wang YC, Jin XY, Lei Z, Liu XJ, Liu Y, Zhang BG, Gong J, Wang LT, Shi LY, Wan DY, Fu X, Wang LP, Ma AJ, Cheng YS, Yang J, He M, Jin XD, Kang Y, Wang B, Zhang ZW, Wu Q. Gastrointestinal manifestations of critical ill heatstroke patients and their associations with outcomes: A multicentre, retrospective, observational study. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(4): 346-366

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i4/346.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i4.346

Owing to the effects of climate change, extreme heat is rapidly becoming a global public health concern. Direct exposure to extreme heat can cause dysregulation of body temperature, leading to heatstroke[1]. Over the past two decades, there has been a 50% increase in heat-related mortality among adults aged 65 and older. As an acute life-threatening condition manifesting an uncontrolled rise in core body temperature, heatstroke presents clinically as a systemic disorder and comprises the following symptoms: Encephalopathy, hypotension, respiratory failure, liver, muscle, coagulopathy and kidney damage[2]. In recent years, some studies have indicated that sustained high body temperature can cause structural and functional damage to the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, resulting in vomiting, diarrhoea, or intolerance to enteral nutrition (EN), which can exacerbate patients' condition[3,4]. Nevertheless, the impact of heatstroke on the GI tract remains to be elucidated.

Located in southwestern part of China, the Sichuan Province is the second largest Chinese province, with a permanent population of more than 80 million. According to the records of the Sichuan meteorological administration, as of May 2022, summer temperatures have reached a historical high since 1961, with two consecutive strong high-temperature periods. One of the most notable consequences of this phenomenon is the significant increase in the number of cases of heatstroke. Accordingly, we conducted a retrospective, multi-center study to examine the demographic characteristics of heatstroke patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) in 2022. Our study primarily aimed to determine the incidence of GI disturbances among patients experiencing heatstroke from various medical centres in the Sichuan Province, with a secondary objective of identifying the risk factors for GI symptoms after heatstroke.

This was a retrospective, multi-center, observational cohort study that involved patients admitted to 83 ICUs located in 16 cities in the Sichuan Province, China between June 1 and October 31, 2022. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of the West China Hospital of Sichuan University (approval No. SCU-2022-1542), in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Given the retrospective nature of this study, the requirement for informed consent was waived.

Inclusion criteria comprised: (1) an age > 18 years; and (2) hospitalization in any type of ICU due to heatstroke or heatstroke-related complications. Patients with heatstroke were diagnosed by front-line medical staff in each center, and the diagnosis was made according to the corresponding clinical manifestations, as well as clinical history[5]. The exclusion criteria included an age < 18; burns; death within 24 h following ICU admission; palliative care; and simultaneous participation in any other nutrition-related interventional studies. Patients whose data is unsuitable for the analysis performed in this study were also excluded. Demographic characteristics were recorded at ICU admission, and clinical variables were recorded daily until up to day 15 of ICU stay or ICU discharge or death. Patients included in the study were managed by physicians in their respective ICUs. The treatment plan for each patient was determined by the attending physician based on the patient's individual condition.

An electronic data capture system (Sichuan Zhikang Technology Co., Ltd, China) was implemented to gather information on heatstroke patients. Data collectors, who were primarily front-line physicians in each centre’s ICU, recorded information on each patient. The data collected was determined after extensive discussion based on expert opinions and in combination with literature review. The trial filling of data was conducted twice through two extensive online meetings with experts from each center to finalize all forms. A training in which the use of the electronic data capture system and heatstroke-related knowledge are explained was conducted in each center before initiating data collection. An online meeting would be hosted every week to check the quality of the data collected during said week. The data underwent a two-step verification process to ensure its completeness and accuracy, and unqualified data was to be collected again. Four researchers (Yu-Cong Wang, Lie-Tao Wang, Lv-Yuan Shi, and Ding-Yuan Wan) reviewed all data independently for completeness and accuracy, and the data management team (Min He, Jing Yang and Qin Wu) conducted a thorough cleaning of the data, identifying any missing information.

Data comprising baseline information, laboratory test results, treatment plan, GI symptoms, nutrition support, and patient outcome were collected in the electronic data capture system. As demographic information, age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and concomitant diseases were collected. Patients’ body temperature at hospital admission, including duration of exposure to heat, first symptoms according to chief complain, nutrition risk screening 2002 (NRS-2002), and Glasgow coma scale (GCS) score were also recorded. Moreover, the average, maximum, and minimum temperature data for the months of May, June, and July in 2022, which was publicly available on the website of the Sichuan meteorological administration, was also collected. The definition of fever in this study was set as a body temperature greater than 37.3 °C as determined through anal temperature measurement. High environment temperature was defined as when the maximum environment temperature reaches or exceeds 35 °C. If the high temperature lasts for more than 3 d, it was defined as a high temperature heat wave. Treatment received during the observation period, including organ support technical, antibiotics, and steroids, were recorded.

GI symptoms were defined as the presence of nausea/vomiting, diarrhoea, flatulence, or bloody stools that do not resolve with medical therapy[6-8]. Specifically, nausea/vomiting in non-intubated patients was defined as the self-reporting of epigastric discomfort followed by vomiting, self-reporting of nausea alone without vomiting, or vomiting alone without nausea. As for intubated patients, nausea/vomiting was defined as the presence of reflux or aspiration for abnormal causes. Diarrhoea was defined as frequent exclusion of loose thin faeces or even watery stools for more than 3 times daily of more than 200 mL each time. Flatulence was defined as awake patients feeling fullness in part or all of the abdomen or partial or total abdominal distention as determined by physical examination in non-awake patients. Bloody stool was defined as having a positive faecal occult blood test more than twice or dark red or black stool. Information on GI symptoms comes from the hourly nursing observation records or daily disease course records.

For patients’ outcome, we collected complications during the observational period, mortality at 15 d, and length of stay in the ICU. The complications in this study included disturbance of water and electrolyte, rhabdomyolysis, myocardial damage, acute kidney injury, acute liver function impairment, and central nervous system impairment. More specifically, disturbance of water and electrolyte was defined as dehydration, oedema, hyperkalaemia, hypokalemia, hypercalcemia, hypocalcaemia, hypermagnesemia or hypomagnesemia, as determined by clinicians. Rhabdomyolysis was defined as muscle pain, tenderness, swelling, weakness, and other muscle involvement and serum creatine kinase levels being significantly elevated more than 5 times the upper limit of normal. Myocardial damage was defined as elevated myocardial enzymes with a normal electrocardiogram. Acute kidney injury was defined according to the kidney disease: Improving Global Outcomes criteria after high temperature exposure. Acute liver function impairment was defined as elevated serum aminotransferase and bilirubin levels above the normal limit after exposure to high temperature with the absence of chronic liver disease, liver failure, coagulation dysfunction, and hepatic encephalopathy. Central nervous system impairment was defined as the occurrence of seizures, motor dysfunction, or sensory dysfunction, including limb hemiplegia, immobility, numbness of the hemi limb, or spontaneous pain in a patient with no history of central nervous system disease.

The primary outcome of the study was the incidence of post-heatstroke GI symptoms, as determined through data collection by trained data collectors. Secondary outcomes included the identification of risk factors for GI dysfunction following heatstroke.

Statistical analysis was performed using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were reported as median and quartile ranges or simple ranges, while categorical variables were summarized as counts and percentages. Items missing more than 10% of their data will be excluded from the analysis, and no imputation was made for missing data. All data were analysed using SPSS Statistics version 25 software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States). Descriptive statistical analyses reflected the distribution of characteristics of the sample population across case and control groups in the form of counts and proportions. T tests and χ2 tests were applied to test the association between case and control group variables. The incidence of confirmed cases was visually represented using a map created with Dychart.com (Wuhan Dysprosium Metadata Technology Co., Ltd, Wuhan, Hubei, China). We developed a logistic regression model to assess the association between the rates of GI dysfunction after heatstroke and several high-risk indicators, including age, initial temperature, initial symptoms, and comorbidities using Graphpad Prism 9 XML project (Graphpad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, United States).

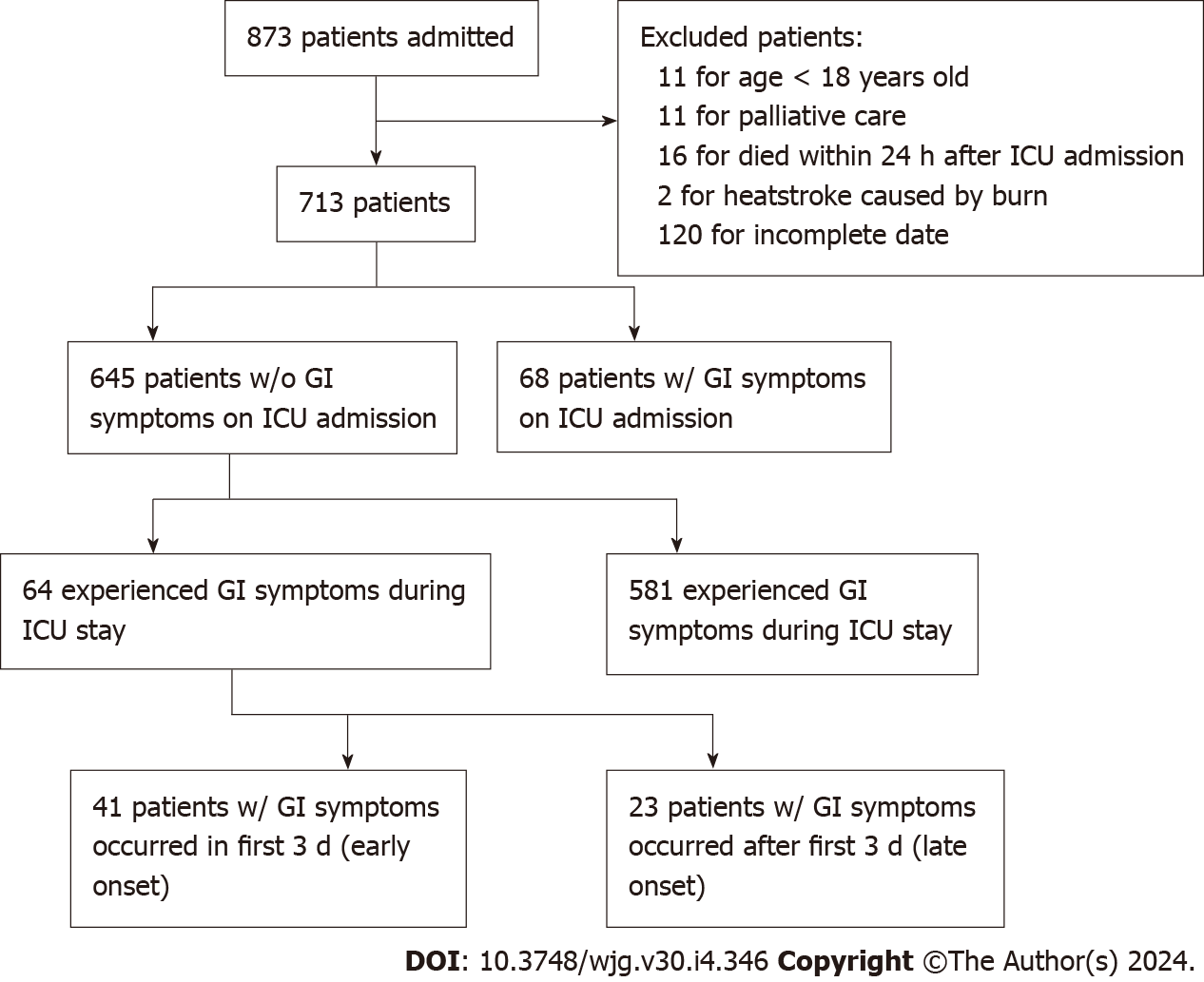

Between June 1, 2022 and October 31, 2022, a total of 873 patients admitted from 83 ICUs across 16 cities due to heatstroke were collected. Of these patients, 160 were excluded as follows: 11 patients were excluded as they were under 18 of age; 2 for heatstroke caused by burn; 16 for mortality within 24 h after ICU admission; 11 for palliative care after ICU admission; and 120 for incomplete data (Figure 1). A total of 713 patients were enrolled in the final analysis. The number of patients enrolled each day during the trial period and daily change in average and maximum temperature in the Sichuan Province are displayed in Supplementary Figure 1. The number of centres from different cities participating in the trial and corresponding total number of patients enrolled are shown in Supplementary Figure 2.

Of the 713 analysed patients, 46.6% were female, and the median age was 72 years [interquartile range (IQR): 64–80; Table 1]. The median body temperature of patients at hospital admission was 40.7 (IQR: 40.0 to 41.3). Around 50% of patients (343/713, 48.10%) were admitted with altered mental states or behaviours. Part of the cohort had at least one underlying illness, such as hypertension (187/713, 26.20%) or diabetes (87/713, 12.20%). Upon admission, the median level of C-reactive protein was elevated (5.0 mg/L, IQR: 1.0–11.8). The same was true for the median levels of procalcitonin (2.7 mg/mL, IQR: 0.5–13.1), and median D-dimer (4.6 mg/L, IQR: 1.8–12.9). A total of 439 patients (61.7%) underwent endotracheal intubation upon ICU admission. At day 15, 349 patients (48.9%) were discharged from the hospital, while 144 (20.2%) died, 187 (26.2%) were still hospitalized, and 33 (4.6%) transferred to another hospital. During hospitalization, acute liver dysfunction was observed in 42.8% (305/713) patients, 41.9% (299/713) experienced acute kidney injury, 39.4% (281/713) experienced myocardial damage, and 35.9% (256/713) experienced central nervous system damage.

| All Patients, (n = 713) | GI Symptoms whether2 | P value | ||

| Yes (n = 132) | No (n = 581) | |||

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 72.0 (64.0-80.0) | 70.0 (59.0-76.0) | 73.0 (64.0-81.0) | 0.076 |

| Distribution, n (%) | ||||

| 0-39 yr | 13 (1.8) | 1 (0.01) | 12 (2.1) | — |

| 40-59 yr | 132 (18.5) | 32 (24.2) | 100 (17.2) | — |

| 60-79 yr | 371 (52.0) | 73 (55.3) | 298 (51.2) | — |

| ≥ 80 yr | 197 (27.6) | 26 (19.6) | 171 (29.4) | — |

| Female sex | 332 (46.6) | 60 (45.4) | 272 (46.8) | 0.561 |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 22.1 (20.3-24.2) | 22.5 (20.0-24.6) | 22.0 (20.3-24.1) | 0.875 |

| GCS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 6.0 (4.0-9.0) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 6.0 (4.0-9.0) | 0.018 |

| NRS-2002 score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 3.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 0.014 |

| Body temperature on admission | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 710 (99.1) | 132 (100.0) | 578 (98.8) | 0.374 |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 40.7 (40.0-41.3) | 41.0 (40.1-42.0) | 40.5 (40.0-41.2) | < 0.001 |

| Heat exposure duration, median (IQR), h | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) | 4.0 (2.0-6.0) | 4.0 (2.0-6.3) | 0.206 |

| Distribution of body temperature on admission, n (%) | ||||

| < 37.3 °C | 6 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (0.1) | — |

| 37.3–38.0 °C | 13 (2.1) | 1 (0.8) | 12 (2.3) | — |

| 38.1–39.0 °C | 59 (9.3) | 8 (6.7) | 51 (9.9) | — |

| 39.1–40.0 °C | 175 (27.7) | 33 (27.7) | 142 (27.7) | — |

| > 40.0 °C | 379 (60.0) | 77 (64.7) | 302 (58.9) | — |

| Number of complaints and symptoms on admission, n (%) | ||||

| < 2 | 169/672 (25.1) | 27/126 (21.4) | 142/546 (26.3) | 0.053 |

| 2-3 | 348/672 (51.8) | 47/126 (37.3) | 301/546 (55.1) | 0.094 |

| > 3 | 155/672 (23.1) | 52/126 (41.3) | 103/546 (18.9) | < 0.001 |

| Complaints and symptoms on admission, n (%) | ||||

| Fever | 476 (66.8) | 93 (70.5) | 383 (65.9 | 0.272 |

| Altered mental state or behavior | 343 (48.1) | 55 (41.7) | 288 (49.6 | 0.177 |

| Dry skin or excessive sweating | 65 (9.1) | 20 (15.1) | 45 (7.7) | < 0.001 |

| Rubefaction | 32 (4.5) | 11 (8.3) | 21 (3.6) | 0.035 |

| Fast pulse | 142 (19.9) | 40 (30.3) | 102 (17.5 | < 0.001 |

| Polypnea | 175 (24.5) | 38 (38.7) | 137 (23.6) | 0.019 |

| Headache | 15 (2.1) | 3 (2.3) | 12 (2.1) | 0.438 |

| Syncope | 309 (43.3) | 85 (64.4) | 224 (38.6) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 102 (14.3) | 27 (20.5) | 75 (12.9) | 0.013 |

| Coexisting disorder, n (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 87 (12.2) | 10 (7.6) | 77 (13.3) | 0.225 |

| Hypertension | 187 (26.2) | 36 (27.3) | 151 (26.0) | 0.985 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 124 (17.4) | 21 (15.9) | 103 (17.7) | 0.697 |

| Chronic cardiac insufficiency | 79 (11.1) | 16 (12.1) | 63 (10.8) | 0.541 |

| Hepatitis B infection | 14 (2.0) | 1 (0.8) | 13 (2.2) | 0.488 |

| Cancer3 | 5 (0.7) | 3 (2.3) | 2 (0.3) | 0.033 |

| Chronic renal disease | 17 (2.4) | 2 (1.5) | 15 (2.6) | 0.149 |

| Immunodeficiency | 9 (1.3) | 3 (2.3) | 6 (1.0) | 0.965 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 239.0 (174.0-323.0) | 238.0 (185.5-300.5) | 248.0 (190.0-336.0) | 0.064 |

| White-cell count, 109/L | 11.7 (8.2-15.5 | 10.0 (6.6-14.4), | 11.7 (8.4-15.5) | 0.032 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 1.3 (0.7-2.4) | 0.9 (0.5-2.3) | 1.0 (0.6-2.1) | 0.746 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 108.0 (73.0-162.0) | 84.0 (45.0-115.0) | 110.0 (75.0-165.5) | 0.147 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 123 (109-138) | 115 (102-127) | 124 (109-138) | 0.014 |

| Albumin, g/L | 37.0 (33.2-40.2) | 33.4 (29.1-43.8) | 37.0 (33.3-40.3) | 0.014 |

| Other findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 5.0 (1.0-11.8) | 11.9 (5.1-32.1) | 5.0 (1.0-12.0) | 0.005 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 2.7 (0.5-13.1) | 3.2 (0.4-8.9) | 2.8 (0.5-12.6) | 0.593 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 367.9 (284.8-547.5) | 327.0 (273.0-507.4) | 362.5 (281.8-524.0) | 0.667 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 79.0 (40.9-191.0) | 115.9 (51.3-269.8) | 74.0 (39.3-168.8) | 0.128 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 38.0 (21.0-85.0) | 48.0 (28.1-104.1) | 36.0 (20.0-77.3) | 0.479 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 17.9 (12.5-25.7) | 18.2 (11.8-258.9), | 17.9 (12.5-25.9) | 0.186 |

| CK-Mb, U/L | 10.0 (2.8-32.0) | 13.6 (4.2-74.6) | 9.9 (2.7-31.7) | 0.539 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 125.0 (89.8-169.2) | 122.0 (84.0-162. | 123.0 (88.4-169.2) | 0.944 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 4.6 (1.8-12.9) | 4.1 (2.1-8.6) | 4.7 (1.7-12.8) | 0.561 |

| Minerals, median (IQR), mmol/L | ||||

| Sodium | 133.3 (129.0-139.0) | 136.0 (132.0-140.0) | 133.6 (129.0-139.0) | 0.158 |

| Potassium | 3.2 (2.9-3.8) | 3.6 (3.0-3.9) | 3.2 (2.9-3.8) | 0.043 |

| Lactate | 3.5 (2.1-5.1) | 3.1 (1.6-4.1) | 3.4 (2.0-5.1) | 0.036 |

| GI symptoms findings, n (%) | ||||

| Duration of GI symptoms, median (IQR), d | — | 4.0 (2.0-7.0) | — | — |

| Diarrhea | — | 99 (75.0) | — | — |

| Flatulence | — | 36 (27.3) | — | — |

| Nausea/vomiting | — | 21 (15.9) | — | — |

| Bloody stools | — | 8 (6.1) | — | — |

| Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Number of complications | ||||

| < 2 | 263 (36.9) | 28 (21.1) | 235 (38.8) | 0.002 |

| 2-3 | 133 (18.7) | 12 (9.2) | 121 (19.8) | 0.025 |

| > 3 | 317 (44.5) | 92 (69.7) | 225 (41.4) | < 0.001 |

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 412 (57.8) | 95 (72.0) | 317 (54.6) | 0.013 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 102 (14.3) | 34 (25.8) | 68 (11.7) | 0.004 |

| Myocardial damage | 281 (39.4) | 70 (53.0) | 211 (36.3) | < 0.001 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 221 (31.0) | 62 (46.9) | 159 (27.4) | 0.006 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 256 (35.9) | 66 (50.0) | 190 (32.7) | 0.001 |

| Acute kidney injury | 299 (41.9) | 83 (62.9) | 216 (37.2) | 0.003 |

| Acute liver function impairment | 305 (42.8) | 81 (61.4) | 224 (38.6) | < 0.001 |

| Central nervous system damage | 256 (35.9) | 74 (56.1) | 182 (31.9) | 0.003 |

| Treatments, n (%) | ||||

| Mechanical ventilation | ||||

| Invasive | 439 (61.7) | 108 (82.6) | 331 (57.1) | < 0.001 |

| Noninvasive | 10 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (1.6) | 0.271 |

| Use of continuous renal-replacement therapy | 24 (3.4) | 7 (9.2) | 17 (2.7) | 0.003 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), d | 2.0 (1.0-4.0) | 4.0 (2.0-7.0) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | ||||

| Hospital discharge | 349 (48.9) | 64 (48.5) | 285 (49.1) | 0.906 |

| Death | 144 (20.2) | 26 (19.7) | 118 (20.3) | 0.874 |

| Still hospitalization | 187 (26.2) | 33 (25.0) | 154 (26.5) | 0.723 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 33 (4.6) | 9 (6.8) | 24 (4.1) | < 0.001 |

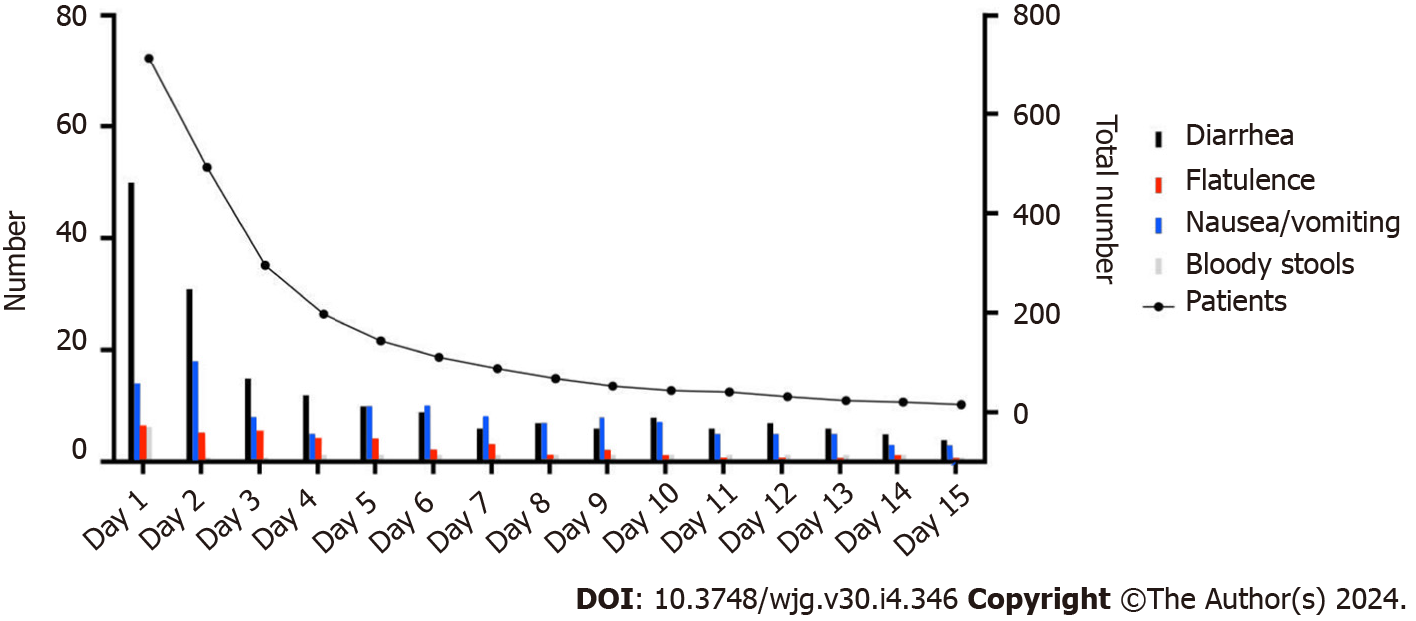

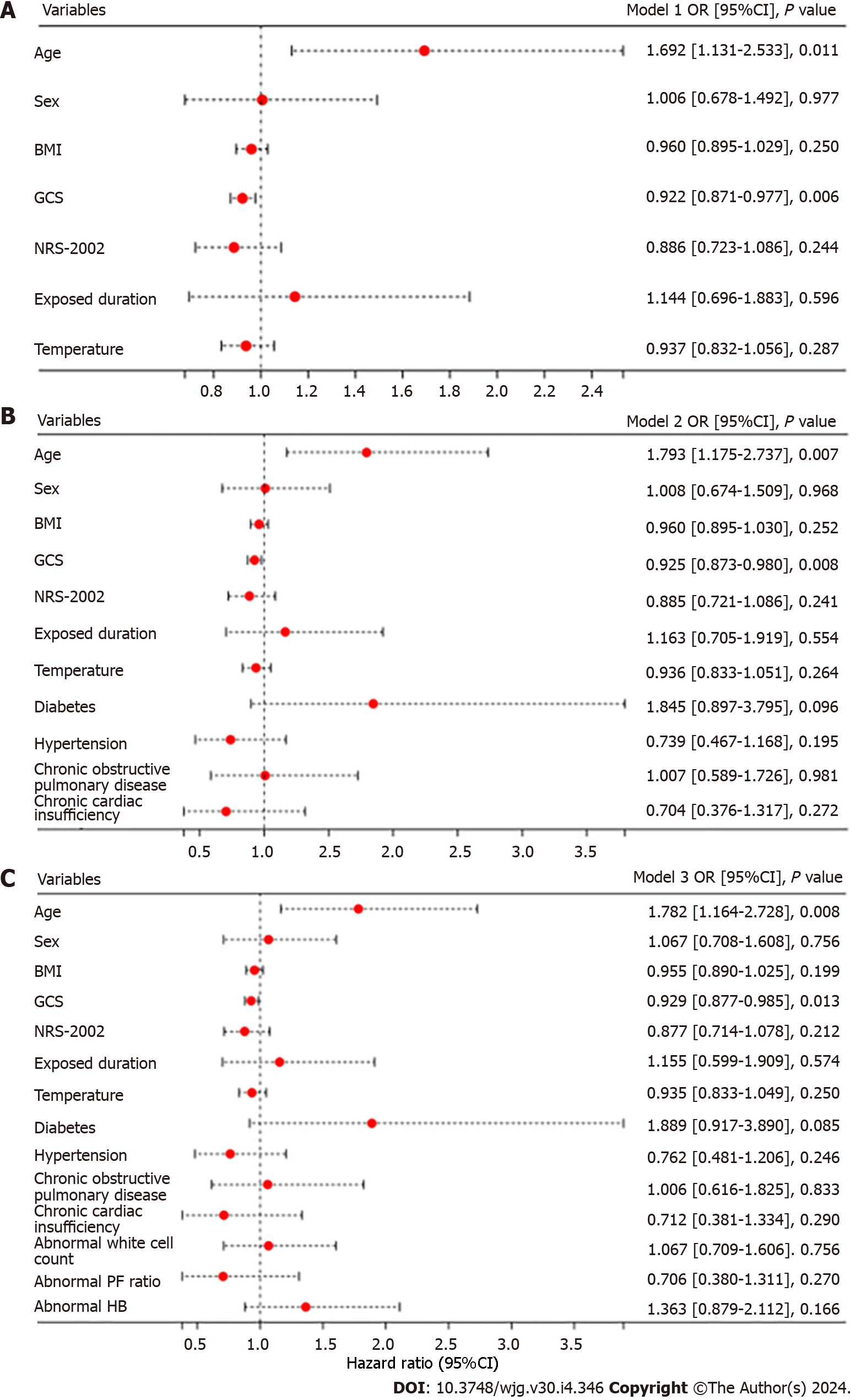

Our study results showed that 18.5% (132/713) of heatstroke patients experienced at least one episode of GI symptoms during ICU stay. Of these patients, 8 (6.1%) experienced bloody stools, 21 (15.9%) experienced nausea/vomiting, 36 (27.3%) experienced flatulence, and 99 (75.0%) experienced diarrhoea (Table 1 and Figure 2). Patients with heatstroke were subsequently categorized into two groups: Those who experienced GI symptoms (n = 132) and those who did not (n = 581) during their ICU stay. There was no difference in the median age of patients between both groups (Table 1). Patients with GI symptoms had significantly lower GCS scores (5.0 vs 6.0, aP = 0.018) and lower NRS-2002 scores (3.0 vs 4.0, bP = 0.014) on admission. There was also no significant difference in the presence of comorbidities upon admission between the groups during the study period, except for a prior history of cancer (2.5% vs 0.5%, cP = 0.033; Table 1). Laboratory results on admission revealed that patients with GI symptoms had significantly lower levels of albumin (33.4 vs 37.0, dP = 0.014) and hemoglobin (115.0 vs 124.0, eP = 0.014) and a higher level of blood lactate (3.1 vs 3.4, eP = 0.036) and C-reactive protein (11.9 vs 5.0, fP = 0.043). It was observed that patients presenting with GI symptoms had an increased likelihood of developing multiple complications, including acute kidney injury (62.9%, gP = 0.003), acute liver function impairment (61.4%, hP < 0.001), and central nervous system damage (56.1%, iP = 0.003). However, the presence of GI symptoms did not have a significant impact on patient mortality. Multivariate logistic regression showed that heatstroke patients who were older than the average year of the cohort were more likely to develop GI symptoms (jP = 0.001; Figure 3A). Moreover, patients with a lower GCS score were prone to have GI symptoms (kP = 0.006; Figure 3A). This positive correlation of GCS score with GI symptoms persisted when we adjusted for complications (Figure 3B) and laboratory results (Figure 3C).

Considering that the predominant GI symptom is diarrhoea, a total of 439 heatstroke patients with endotracheal intubation shortly after ICU admission were analysed to explore the relationship between GI symptoms and EN therapy. We found that the presence of GI symptoms was not associated with EN therapy (Table 2). There was no statistical difference in the proportion of EN support, amount of calories and proteins, and total volume received on admission between the patients who underwent EN therapy. Of note, EN therapy was initiated in only a small proportion (139/439, 31.7%) of intubated patients within 48 h after ICU admission, as shown in Table 3. Patients who did not start EN within 48 h of ICU admission had a significantly lower GCS score (5.0 vs 4.0, lP = 0.002), experienced more GI symptoms after ICU admission (22.3% vs 12.9%, mP = 0.021), and had a longer ICU stay (3.0 vs 2.0, nP < 0.001). Logistic regression analysis showed that GI symptoms were an independent risk factor for not initiating early EN (oP = 0.037; Supple

| All intubated patients (n = 439) | GI symptoms whether2 | P value | ||

| Yes (n = 108) | No (n = 331) | |||

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 71.0 (63.0-80.0) | 72.0 (64.0-80.0) | 69.5 (59.8-78.0) | 0.202 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 197 (44.9) | 49 (45.4) | 148 (44.7) | 0.905 |

| GCS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.0 (4.0-5.0) | 0.204 |

| NRS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 3.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 0.057 |

| Body temperature on admission | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 439 (100.0) | 108 (100.0) | 331 (100.0) | 0.348 |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-41.8) | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 41.0 (40.0-41.6) | 0.497 |

| Complaints and symptoms on admission, n (%) | ||||

| Fever | 296 (67.4) | 76 (70.4) | 220 (66.5) | 0.452 |

| Altered mental state or behavior | 205 (46.7) | 41 (38.0) | 164 (49.5) | 0.036 |

| Dry skin or excessive sweating | 45 (10.3 | 20 (18.5) | 25 (7.6) | 0.001 |

| Rubefaction | 17 (3.9) | 9 (8.3) | 8 (2.4) | 0.006 |

| Fast pulse | 99 (22.6) | 34 (31.5) | 65 (19.6) | 0.105 |

| Polypnea | 122 (27.8) | 31 (28.7) | 91 (27.5) | 0.807 |

| Headache | 7 (1.6) | 2 (18.5) | 5 (1.5) | 0.805 |

| Syncope | 207 (47.2) | 70 (64.8) | 137 (41.4) | < 0.001 |

| Other | 61 (13.9) | 71 (65.7) | 40 (12.1) | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 225.0 (135.5-306.5) | 221.0 (148.7-308.0) | 226.0 (155.0-305.5) | 0.999 |

| White-cell count, 109/L | 11.7 (8.1-15.6) | 11.8 (8.0-15.8) | 11.7 (8.1-15.6) | 0.405 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 1.7 (0.8-2.8) | 1.6 (0.8-2.8) | 1.8 (0.8-28) | 0.279 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 92.0 (56.0-138.0) | 83.5 (55.5-114.5) | 97.0 (59.0-141.0) | 0.143 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 124.0 (109.0-139.0) | 121.0 (108.3-135.8) | 125.0 (110.0-139.0) | 0.053 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35.3 (32.5-38.9) | 34.5 (31.8-38.0) | 35.3 (32.5-38.9) | 0.028 |

| EN support | ||||

| Early (< 48 h) EN, n (%) | 68 (15.5) | 13 (12.0) | 55 (16.6) | 0.253 |

| Average EN calorie, median (IQR), kcal/d | 1000.0 (750.0-1500.0) | 1000.0 (750.0-1500.0) | 1000.0 (750.0-1500.0) | 0.559 |

| Average EN protein, median (IQR), g/d | 28.0 (17.0-56.0) | 30.0 (17.0-56.0) | 28.0 (20.0-56.0) | 0.867 |

| Average EN volume, median (IQR), mL/d | 600.0 (150.0-1150.0) | 625.0 (142.5-1200.0) | 600.0 (150.0-1082.5) | 0.31 |

| Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 271 (61.7) | 89 (82.4) | 187 (56.5) | < 0.001 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 81 (18.5) | 31 (28.7) | 50 (15.1) | 0.002 |

| Myocardial damage | 216 (49.2) | 63 (58.0) | 153 (46.2) | 0.029 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 172 (39.2) | 54 (50.0) | 118 (35.6) | 0.001 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 226 (51.5) | 62 (57.4) | 164 (49.5) | 0.156 |

| Acute kidney injury | 233 (53.1) | 77 (71.3) | 156 (47.1) | < 0.001 |

| Acute liver function impairment | 332 (75.6) | 73 (65.6) | 159 (48.0) | < 0.001 |

| Central nervous system damage | 206 (46.9) | 65 (60.2) | 141 (42.6) | 0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | ||||

| Hospital discharge | 210 (47.8) | 51 (47.2) | 159 (48.0) | 0.234 |

| Death | 123 (28.0) | 24 (22.2) | 99 (29.9) | 0.122 |

| Still hospitalization | 78 (17.8) | 24 (22.2) | 54 (16.3) | 0.163 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 28 (6.4) | 9 (8.3) | 19 (5.7) | 0.338 |

| All intubated patients (n = 439) | EN therapy whether ≤ 48 h | P value | ||

| Yes (n = 139) | No (n = 300) | |||

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 71.0 (63.0-80.0) | 72.0 (63.0-80.0) | 71.0 (63.0-79.0) | 0.801 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 197 (44.9) | 62 (46.8) | 135 (43.6) | 0.938 |

| GCS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5 .0) | 0.002 |

| NRS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 5.0 (4.0-6.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 0.017 |

| Body temperature on admission | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 439 (100.0) | 139 (100.0) | 300 (100.0) | — |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-41.8) | 41.0 (40.0-41.5) | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 0.154 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 225.0 (135.5-306.5) | 226.0 (164.0-287.0) | 223.0 (128.0-316.0) | 0.825 |

| White-cell count, 109/L | 11.7 (8.1-15.6) | 12.4 (8.6-16.8) | 11.3 (8.0-15.0) | 0.290 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 1.7 (0.8-2.8) | 1.5 (0.7-2.3) | 1.9 (0.9-3.0) | 0.105 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 92.0 (56.0-138.0) | 101.0 (66.8-147.3) | 88.0 (54.0-130.0) | 0.039 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 124.0 (109.0-139.0) | 122.0 (109.0-136.0) | 124.5 (109.0-140.0) | 0.311 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35.3 (32.5-38.9) | 35.1 (32.0-38.5) | 35.4 (32.5-39.0) | 0.544 |

| GI symptoms2, n (%) | ||||

| Total patients | 85 (19.4) | 18 (12.9) | 67 (22.3) | 0.021 |

| Diarrhea | 60 (13.7) | 13 (9.4) | 47 (15.7) | 0.073 |

| Flatulence | 25 (5.7) | 7 (5.0) | 18 (6.0) | 0.685 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 14 (3.2) | 7 (5.0) | 7 (2.3) | 0.134 |

| Bloody stools | 8 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (2.6) | 0.052 |

| Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 271 (61.7) | 79 (56.8) | 192 (64.0) | 0.151 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 81 (18.5) | 20 (11.6) | 61 (20.3) | 0.135 |

| Myocardial damage | 216 (49.2) | 65 (46.8) | 151 (50.3) | 0.486 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 172 (39.2) | 50 (36.0) | 122 (40.7) | 0.349 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 226 (51.5) | 74 (53.2) | 152 (50.7) | 0.616 |

| Acute kidney injury | 233 (53.1) | 66 (47.5) | 167 (55.7) | 0.110 |

| Acute liver function impairment | 332 (75.6) | 74 (53.2) | 258 (86.0) | < 0.001 |

| Central nervous system damage | 206 (46.9) | 62 (44.6) | 144 (48.0) | 0.507 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Use of continuous renal-replacement therapy, n (%) | 34 (7.7) | 10 (8.1) | 20 (7.5) | 0.826 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), d | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 3.0 (2.0-5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | ||||

| Hospital discharge | 210 (47.8) | 68 (48.9) | 142 (47.3) | 0.757 |

| Death | 123 (28.0) | 24 (17.3) | 99 (33.3) | < 0.001 |

| Still hospitalization | 78 (17.8) | 36 (25.9) | 42 (14.0) | 0.002 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 28 (6.4) | 11 (7.9) | 17 (5.7) | 0.370 |

| All intubated patients (n = 439) | Full EN whether | P value | ||

| Yes (n = 173) | No (n = 266) | |||

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 71.0 (63.0-80.0) | 72.0 (63.0-80.0) | 71.0 (63.0-79.0) | 0.801 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 197 (44.9) | 81 (46.8) | 116 (43.6) | 0.509 |

| GCS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 6.0 (4.0-8.0) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 0.002 |

| NRS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 0.193 |

| Body temperature on admission | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 439 (100.0) | 173 (100.0) | 266 (100.0) | — |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-41.8) | 41.0 (40.0-41.4) | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 0.128 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 225.0 (135.5-306.5) | 246.0 (191.0-334.0) | 222.0 (134.0-315.0) | 0.226 |

| White-cell count, 109/L | 11.7 (8.1-15.6) | 12.6 (9.4-16.7) | 11.4 (8.0-15.3) | 0.287 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 1.7 (0.8-2.8) | 0.8 (0.5-1.6) | 2.0 (0.9-3.0) | 0.084 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 92.0 (56.0-138.0) | 71.5 (37.0-113.8) | 89.0 (54.0-132.5) | 0.011 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 124.0 (109.0-139.0) | 119.0 (107.5-129.0) | 125.0 (110.0-140.0) | 0.002 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35.3 (32.5-38.9) | 32.0 (29.0-35.2) | 35.5 (32.5-39.2) | < 0.001 |

| GI symptoms2, n (%) | ||||

| Total patients | 85 (19.4) | 25 (14.5) | 60 (22.6) | 0.036 |

| Diarrhea | 60 (13.7) | 17 (9.8) | 43 (16.2) | 0.059 |

| Flatulence | 25 (5.7) | 8 (4.6) | 17 (6.4) | 0.435 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 14 (3.2) | 7 (4.0) | 7 (2.6) | 0.409 |

| Bloody stools | 8 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (3.1) | 0.021 |

| Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 271 (61.7) | 105 (60.7) | 166 (62.4) | 0.718 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 81 (18.5) | 20 (11.6) | 55 (20.7) | 0.013 |

| Myocardial damage | 216 (49.2) | 83 (48.0) | 133 (50.0) | 0.678 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 172 (39.2) | 60 (34.7) | 112 (42.1) | 0.119 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 226 (51.5) | 92 (53.2) | 134 (50.4) | 0.566 |

| Acute kidney injury | 233 (53.1) | 79 (45.7) | 154 (57.9) | 0.012 |

| Acute liver function impairment | 332 (75.6) | 94 (54.3) | 138 (51.9) | 0.615 |

| Central nervous system damage | 206 (46.9) | 80 (46.2) | 126 (47.4) | 0.817 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Use of continuous renal-replacement therapy, n (%) | 34 (7.7) | 14 (8.1) | 20 (7.5) | 0.826 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), d | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 2.0 (1.0-2.0) | 3.0 (1.0-4.0) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | ||||

| Hospital discharge | 210 (47.8) | 83 (48.0) | 127 (47.7) | 0.962 |

| Death | 123 (28.0) | 29 (16.8) | 94 (35.3) | < 0.001 |

| Still hospitalization | 78 (17.8) | 46 (26.6) | 82 (20.8) | 0.339 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 28 (6.4) | 15 (8.7) | 13 (4.9) | 0.113 |

Since the definition of GI manifestations was composite, we subsequently explore whether there was difference in the characteristics of patients with different symptoms. We selected patients with a single symptom and divided them into 3 groups according to different GI manifestations (Table 5). There was a statistically significant difference in temperature on admission between patients with diarrhoea, flatulence, and nausea/vomiting (uP = 0.003). Notably, there were significant differences in complications between the three subgroups, except for complications of disturbance of water and electrolyte. Although mortality was not different between subgroups, the difference in the number of patients who were still hospitalized was statistically significant (vP = 0.025).

| GI Symptoms2 | P value | |||

| Diarrhea (n = 88) | Flatulence (n = 27) | Nausea/vomiting (n = 15) | ||

| Characteristic | ||||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 65.0 (56.0-76.0) | 69.0 (56.0-79.0) | 68.0 (57.5-78.0) | 0.565 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 35.0 (39.8) | 14.0 (51.8) | 6 (40.0) | 0.529 |

| GCS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 6.0 (3.0-9.5) | 4.0 (3.0-6.0) | 0.540 |

| NRS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 4.5 (4.0-5.0) | 4.0 (3.0-5.0) | 0.193 |

| Body temperature admission | ||||

| Patients, n (%) | 88.0 (100.0) | 27.0 (100.0) | 15.0 (100.0) | — |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 40.0 (39.8-41.0) | 40.1 (39.8-41.0) | 0.003 |

| Complaints and symptoms, n (%) | ||||

| Fever | 62.0 (70.5) | 20.0 (74.0) | 8.0 (53.3) | 0.343 |

| Altered mental state or behavior | 35.0 (39.8) | 13.0 (48.1) | 4.0 (26.7) | 0.395 |

| Dry skin or excessive sweating | 19.0 (21.6) | 2.0 (7.4) | 2.0 (13.3) | 0.215 |

| Rubefaction | 7.0 (8.0) | 2.0 (7.4) | 1.0 (6.7) | 0.983 |

| Fast pulse | 32.0 (36.4) | 6.0 (22.2) | 4.0 (26.7) | 0.344 |

| Polypnea | 29.0 (33.0) | 6.0 (22.2) | 3.0 (20.0) | 0.397 |

| Headache | 1.0 (1.1) | 3.0 (11.1) | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.024 |

| Syncope | 63.0 (71.6) | 13.0 (48.1) | 8.0 (53.3) | 0.052 |

| Other | 22.0 (25.0) | 4.0 (14.8) | 2.0 (13.3) | 0.378 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | ||||

| White-cell count, 109/L | 13.0 (8.2-16.3) | 13.0 (8.2-16.3) | 13.0 (8.2-16.3) | 0.210 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 122.0 (110.3-136.0) | 125.0 (110.5-137.5) | 120.0 (107.3-130.0) | 0.589 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35.8 (32.9-38.8) | 35.3 (32.0-39.5) | 36.7 (29.3-39.5) | 0.969 |

| Complications, n (%) | ||||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 63 (71.6) | 20 (74.0) | 11 (73.3) | 0.085 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 24 (27.3) | 6 (22.2) | 4 (26.7) | 0.003 |

| Myocardial damage | 49 (55.7) | 11.0 (40.7) | 9 (60.0) | 0.008 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 40 (45.5) | 9 (33.3) | 6 (40.0) | 0.010 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 46 (52.3) | 9 (33.3) | 6 (40.0) | 0.012 |

| Acute kidney injury | 52 (59.1) | 15 (55.6) | 10 (66.7) | 0.024 |

| Acute liver function impairment | 52 (59.1) | 15 (55.6) | 10 (66.7) | 0.024 |

| Central nervous system damage | 48 (54.5) | 15 (55.6) | 9 (60.0) | 0.019 |

| Treatments | ||||

| Use of continuous renal-replacement therapy, n (%) | 7 (8.0) | 3 (11.1) | 2 (13.3) | < 0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay, median (IQR), d | 1.0 (1.0-2.0) | 1.0 (1.0-1.0) | 2.0 (1.0-3.0) | 0.015 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | ||||

| Hospital discharge | 44.0 (50.0) | 11.0 (40.7) | 5.0 (33.3) | 0.400 |

| Death | 16.0 (18.2) | 2.0 (7.4) | 4.0 (26.7) | 0.240 |

| Still hospitalization | 19.0 (21.6) | 13.0 (48.1) | 5.0 (33.3) | 0.025 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 9.0 (10.2) | 1.0 (3.7) | 1.0 (6.7) | 0.547 |

As we observed that the onset of GI symptoms was significantly different between patients, we further divided patients with GI symptoms into two categories: Those with GI symptoms on ICU admission and those with GI symptoms developed during ICU stay. The patient characteristics of both groups are shown in Table 6. The patients who had GI symptoms on admission were younger (vP = 0.050), had a higher BMI (22.7 vs 21.1, wP = 0.050), and had a lower nutrition risk screening (NRS-2002) score on admission (3.0 vs 4.0, xP = 0.009) than had those who developed symptoms later on. Patients who had less GI symptoms on admission had a lower number of comorbidities, including diabetes (1/68, 1.5% vs 9/64, 14.1%, yP = 0.009), but more complications, including haemorrhage of the digestive tract (23/68, 33.8% vs 12/64, 18.8%) and disseminated intravascular coagulation (38/68, 55.9% vs 24/64, 37.5%). Nevertheless, there is no difference in mortality and ICU length of stay.

| GI symptoms1 | P value | ||

| On admission (n = 68) | Developed in ICU stay (n = 64) | ||

| Characteristic | |||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 67.0 (57.0-76.0) | 70.0 (64.0-80.0) | 0.050 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 28 (41.2) | 32 (50.0) | 0.310 |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 22.7 (20.2-24.8) | 21.1 (20.0-23.3) | 0.050 |

| GCS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0-8.0) | 5.0 (3.0-7.0) | 0.814 |

| NRS score at ICU admission, median (IQR) | 3.0 (3.0-4.5) | 4.0 (3.0-6.0) | 0.009 |

| Fever on admission | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 68 (100.0) | 64 (100.0) | — |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 41.0 (40.0-41.3) | 0.265 |

| Complaints and symptoms on admission, n (%) | |||

| Fever | 54 (79.4) | 39 (60.9) | 0.020 |

| Altered mental state or behavior | 25 (36.8) | 30 (46.9) | 0.239 |

| Dry skin or excessive sweating | 13 (19.1) | 7 (109) | 0.190 |

| Rubefaction | 5 (7.4) | 6 (9.4) | 0.674 |

| Fast pulse | 27 (39.7) | 13 (20.3) | 0.015 |

| Polypnea | 24 (35.3) | 14 (21.9) | 0.089 |

| Headache | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.524 |

| Syncope | 49 (72.1) | 36 (56.2) | 0.058 |

| Other | 20 (29.4) | 7 (109) | 0.009 |

| Coexisting disorder, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes | 1 (1.5) | 9 (14.1) | 0.009 |

| Hypertension | 15 (22.1) | 21 (32.8) | 0.166 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 11 (16.2) | 10 (15.6) | 0.931 |

| Chronic cardiac insufficiency | 5 (7.4) | 11 (17.2) | 0.084 |

| Hepatitis B infection | 1 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0.330 |

| Cancer | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.524 |

| Chronic renal disease | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.1) | 0.142 |

| Immunodeficiency | 1 (1.5) | 2 (3.1) | 0.524 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| PaO2/FiO2 ratio | 240.0 (141.8-316.0) | 217.0 (165.0-285.8) | 0.775 |

| White-cell count, 109/L | 12.1 (7.8-16.2) | 11.8 (8.2-14.2) | 0.667 |

| Lymphocyte count, 109/L | 2.1 (1.0-3.3) | 1.2 (0.6-2.0) | 0.023 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 90.0 (60.5-120.3) | 98.5 (67.8-150.5) | 0.256 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 126.0 (112.0-135.5) | 118.5 (103.5-137.5) | 0.106 |

| Albumin, g/L | 36.5 (33.3-40.0) | 35.0 (32.1-38.6) | 0.093 |

| Other findings, median (IQR) | |||

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 5.0 (0.5-10.0) | 5.0 (1.0-14.9) | 0.605 |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | 1.4 (0.4-8.2) | 9.3 (2.2-29.3) | 0.055 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase, U/L | 465.0 (314.3-810.3) | 382.5 (282.8-537.8) | 0.263 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, U/L | 123.9 (58.3-272.3) | 107.2 (44.0-268.3) | 0.152 |

| Alanine aminotransferase, U/L | 46.5 (26.2-112.4) | 48.0 (27.1-89.5) | 0.247 |

| Total bilirubin, μmol/L | 18.5 (12.8-25.9) | 15.6 (10.1-23.0) | 0.211 |

| CK-Mb, U/L | 10.1 (2.9-33.1) | 8.7 (3.3-41.0) | 0.214 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 131.1 (105.3-182.8) | 137.0 (97.5-171.0) | 0.628 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 3.9 (2.5-11.5) | 4.6 (1.9-12.7) | 0.524 |

| Minerals, median (IQR), mmol/L | |||

| Sodium | 132.0 (129.0-137.0) | 133.9 (128.5-136.8) | 0.959 |

| Potassium | 3.3 (3.0-3.9) | 3.5 (2.9-3.8) | 0.849 |

| Lactate | 4.2 (3.1-5.5) | 3.6 (2.4-5.3) | 0.649 |

| Complication, n (%) | |||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 51 (75.0) | 44 (68.8) | 0.424 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 21 (30.9) | 13 (20.3) | 0.165 |

| Myocardial damage | 40 (58.8) | 30 (46.9) | 0.122 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 38 (55.9) | 24 (37.5) | 0.034 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 39 (57.4) | 27 (42.2) | 0.082 |

| Acute kidney injury | 45 (66.2) | 38 (59.4) | 0.419 |

| Acute liver function impairment | 41 (60.3) | 40 (62.5) | 0.795 |

| Central nervous system damage | 42 (61.8) | 30 (46.9) | 0.086 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | |||

| Hospital discharge | 35 (51.5) | 29 (45.3) | 0.479 |

| Death | 17 (25.0) | 9 (14.1) | 0.114 |

| Still hospitalization | 13 (19.1) | 20 (31.3) | 0.108 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 3 (4.4) | 6 (9.4) | 0.258 |

We divided patients who developed GI symptoms during their ICU stay into the early-onset (< 3 d of ICU stay) and late-onset groups (≥ 3 d of ICU stay) groups. As shown in Table 7, there was a significant statistical difference in EN support between the two groups. Fewer patients received EN support in the early-onset than in the late-onset group (29/41, 70.7 vs 22/23, 95.7%, zP < 0.001). The early-onset group received less EN calorie [752.0 kcal/d (IQR: 500.0–1007.5) vs 1292.0 kcal/d (IQR: 750.0-1560.0)], protein [20.0 g/d (IQR: 17.6–32.5) vs 28.0 g/d (IQR: 15.0–57.0)], and EN volume [600.0 mL/d (IQR: 147.5–1000.0) vs 900.0 mL/d (IQR: 461.2–1500.0)]. Moreover, patients in the early-onset group received EN support for a shorter time than did those in the late-onset group [3.0 d (IQR: 1.8–5.0) vs 7.0 d (IQR: 4.0–11.0)].

| Early onset, n = 41 | Late onset, n = 23 | P value | |

| Characteristic2 | |||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 69.0 (62.3-79.0) | 64.0 (56.0-76.0) | 0.856 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 23 (56.1) | 8 (34.8) | 0.102 |

| Fever on admission | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 41 (100.0) | 23 (100.0) | — |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 40.7 (39.6-41.3) | 0.338 |

| Body temperature on admission, n (%) | |||

| Fever | 23 (56.1) | 15 (65.2) | 0.475 |

| Altered mental state or behavior | 19 (46.3) | 11 (47.8) | 0.909 |

| Dry skin or excessive sweating | 4 (9.8) | 3 (13.0) | 0.686 |

| Rubefaction | 4 (9.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.889 |

| Fast pulse | 11 (26.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.084 |

| Polypnea | 9 (22.0) | 5 (21.7) | 0.984 |

| Headache | 2 (4.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0.282 |

| Syncope | 21 (51.2) | 13 (56.5) | 0.683 |

| Other | 3 (7.3) | 4 (17.4) | 0.215 |

| EN support | |||

| EN, n (%) | 29 (70.7) | 22 (95.7) | < 0.001 |

| Average EN calorie, median (IQR), kcal/d | 752.0 (500.0-1007.5) | 1292.0 (750.0-1560.0) | < 0.001 |

| Average EN protein, median (IQR), g/d | 20.0 (17.6-32.5) | 28.0 (15.0-57.0) | 0.003 |

| Average EN volume, median (IQR), ml/d | 600.0 (147.5-1000.0) | 900.0 (461.2-1500.0) | < 0.001 |

| Duration of EN, median (IQR), d | 3.0 (1.8-5.0) | 7.0 (4.0-11.0) | 0.011 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | |||

| White-cell count, 109/L | 10.6 (7.8-13.5) | 13.5 (8.6-15.8) | 0.351 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 117.0 (106.0-128.0) | 128.5 (105.3-141.5) | 0.187 |

| Albumin, g/L | 35.4 (33.7-39.2) | 34.4 (30.8-36.8) | 0.239 |

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 26 (63.4) | 17 (73.9) | 0.391 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 6 (14.6) | 6 (26.1) | 0.261 |

| Hemorrhage of digestive tract | 8 (19.5) | 3 (13.1) | 0.511 |

| Myocardial damage | 17 (41.5) | 12 (52.2) | 0.409 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 14 (34.1) | 9 (39.1) | 0.691 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 17 (41.5) | 6 (26.1) | 0.855 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | |||

| Hospital discharge | 17 (41.5) | 11 (47.8) | 0.622 |

| Death | 7 (17.1) | 2 (8.7) | 0.355 |

| Still hospitalization | 12 (29.3) | 8 (34.8) | 0.648 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 4 (9.8) | 2 (8.7) | 0.889 |

To further explore the relationship between the duration of GI symptoms and prognosis of heatstroke patients, we stratified patients into those who had GI symptoms for more than 4 d and those who did for had GI symptoms for less than 4 d, as shown in Table 8. Patients with GI symptoms for at least 4 d had lower albumin levels (37.0 g/L vs 34.4 g/L, P = 0.310) and more complications, including disseminated intravascular coagulation (27.8% vs 54.2%, P = 0.007) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (12.0% vs 54.2%, P < 0.001). They also showed higher recovery rates than did those who had symptoms for more than 4 d (56.3% vs 27.8%, P = 0.004).

| Last < 4 d, n = 96 | Last ≥ 4 d, n = 36 | P value | |

| Characteristic | |||

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 70.0 (61.5-78.3) | 67.0 (59.0-76.0) | 0.659 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 43 (44.8) | 17 (47.2) | 0.803 |

| Body temperature on admission | |||

| Patients, n (%) | 96 (100.0) | 36 (100.0) | - |

| Temperature, median (IQR), °C | 41.0 (40.0-41.5) | 41.0 (40.0-42.0) | 0.948 |

| Complaints and symptoms on admission, n (%) | |||

| Fever | 69 (71.9) | 24 (66.7) | 0.559 |

| Altered mental state or behavior | 39 (40.6) | 16 (44.4) | 0.692 |

| Dry skin or excessive sweating | 16 (16.7) | 4 (11.1) | 0.428 |

| Rubefaction | 9 (9.4) | 2 (5.6) | 0.889 |

| Fast pulse | 32 (33.3) | 8 (22.2) | 0.767 |

| Polypnea | 31 (32.3) | 7 (19.4) | 0.147 |

| Headache | 2 (2.1) | 1 (2.8) | 0.811 |

| Syncope | 67 (69.8) | 18 (50.0) | 0.034 |

| Other | 19 (19.8) | 8 (22.2) | 0.758 |

| Laboratory findings, median (IQR) | |||

| White-cell count, 109/L | 11.0 (7.5-14.2) | 7.3 (9.2-16.3) | 0.062 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 122.0 (110.5-135.5) | 118.0 (106.0-132.5) | 0.941 |

| Albumin, g/L | 37.0 (33.3-39.7) | 34.4 (31.1-36.4) | 0.031 |

| Complications, n (%) | |||

| Disturbance of water and electrolyte | 69 (71.9) | 20 (55.6) | 0.075 |

| Rhabdomyolysis | 28 (29.2) | 6 (16.7) | 0.144 |

| Hemorrhage of digestive tract | 28 (29.2) | 7 (19.4) | 0.26 |

| Myocardial damage | 50 (52.1) | 20 (55.6) | 0.722 |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | 27 (27.8) | 20 (54.2) | 0.007 |

| Acute respiratory distress syndrome | 12 (12.0) | 20 (54.2) | < 0.001 |

| Clinical outcomes at data cutoff, n (%) | |||

| Hospital discharge | 54 (56.3) | 10 (27.8) | 0.004 |

| Death | 17 (17.7) | 9 (25.0) | 0.348 |

| Still hospitalization | 21 (21.9) | 12 (33.3) | 0.176 |

| Transferred to another hospital | 4 (4.2) | 5 (13.9) | 0.048 |

In this retrospective, multi-center study, we reported the incidence of GI manifestations among critically ill adult patients with heatstroke admitted to ICUs in the Sichuan Province, China. Our data demonstrated that patients with GI symptoms had a significantly longer ICU stay compared with those without. As a manifestation of systemic organ damage in heatstroke, the appearance of GI symptoms affect patients’ EN therapy outcomes. Patients with older age and a lower GCS score on admission were more likely to experience GI symptoms. Our study provides valuable real-world evidence regarding the associations between heatstroke and GI symptoms with, to our knowledge, the highest number of patients from multiple centres to date.

Conventionally, critically ill patients with have GI dysfunction; however, there is little evidence supporting this phenomenon among heatstroke patients. Due to the lack of standardization of the diagnostic and therapeutic approaches, in this study, we evaluated the GI tract according to its symptoms and found that 18.5% of patients with heatstroke suffered from said symptoms during their stay. Compared with other non-heat stroke critically ill patients, the incidence of GI symptoms in our cohort is relatively low[9,10]. This is partly due to the fact that our study only used symptoms to evaluate GI function, though other high-incidence studies generally included physical examination, including that for bowel sounds, for comprehensive evaluation. When comparing the same symptoms, such as vomiting, between patients with heatstroke and those in the ICU, we observed that the incidence of GI symptoms in heatstroke patients is still lower than that of patients in the general ICU. One reason behind this is that heatstroke patients do not have GI structural damage from the perspective of pathogenesis, but patients in the general ICU comprise those who underwent abdominal surgery, that is, those who already have GI structural disorders. Another reason is that our study only assessed GI symptoms without other indicators such as physical examination, which may have led to the underestimation of the incidence of GI dysfunction. Nevertheless, our research suggests that GI injury is an important high-incidence mani-festation of organ failure among heatstroke patients.

Our study found that heatstroke patients with older age and lower GCS score were more likely to experience GI symptoms. Multiple clinical studies had described risk factors for GI dysfunction in critically ill patients, including older age, larger BMI, lower Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation II and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment scores, surgical laparotomy, and use of mechanical ventilation, analgesic sedation, and vasopressors[9-11]. Similar to other studies, our study also observed that older patients were more likely to experience GI symptoms after heatstroke. Of note, our study found that the degree of nervous system damage, as quantified by the GCS score, is also related to the occurrence of GI dysfunction. This may be because heat damages the enteric nervous system, as well as the central nervous system. Moreover, patients with lower GCS scores were more likely to receive mechanical ventilation and vasopressors, posing an impact on the intestinal blood supply and, consequently, possibly leading to GI failure. The causes of GI dysfunction caused by heatstroke warrant further research.

We also observed that the presence of GI symptoms may affect EN support therapy. In our study, we found heatstroke patients who did not receive EN therapy within 48 h after ICU admission experienced more GI symptoms with more complications, longer ICU stay, and higher ICU mortality. The emergence of GI symptoms is the reason why EN cannot be started. Simultaneously, the failure to start EN support is also a reason for the deterioration of GI function. We also observed that a considerable proportion of patients with heat stroke still cannot implement total EN within 2 wk, suggesting that, for patients with heatstroke, further research to develop individualized nutrition support strategies is warranted.

We also performed various subgroup analyses to discuss different GI symptoms and whether their timing and duration had an impact on patient prognosis. First, we found that patients with different GI symptoms have different clinical features. Different symptoms may indicate that the severity of heatstroke in these patients varies, and whether this reflects their prognosis to some extent requires further study. The onset of GI symptoms in patients also differed. Overall, the earlier the GI symptoms appeared, the severer the patient's condition was. At the same time, due to GI symptoms, such patients could not tolerate EN or could not meet EN standards, further impairing their GI function and forming a vicious circle. Better approaches for EN support in these patients are warranted. Finally, we discussed the duration of the patient's GI symptoms. This was the same as we previously realized: The longer the duration of GI symptoms, the worse their prognosis. These patients were unable to start EN therapy early on. In contrast, they were more likely to have GI microcirculation disorders and damage to the intestinal barrier.

Currently, the cause of GI dysfunction caused by heatstroke is not particularly clear. Several reports have documented increased intestinal permeability during exercise with and without heat stress[4,12,13]. A murine model of classic heatstroke that induced a body core temperature as high as 42.7 °C showed considerable gut histological injury[14,15]. Studies have shown that one of the important mechanisms of heatstroke is the excessive opening of intestinal tight junctions, destruction of intestinal cell structure and function, increase in intestinal mucosal permeability, and introduction of endotoxin into the blood[16,17]. One of the most frequently mentioned mechanisms of how heatstroke causes GI symptoms is the leaky gut hypothesis. Our results also suggest that while heat can cause changes in the state of consciousness caused by central nervous system damage, it may also cause damage to the enteric nervous system, thereby causing GI dysfunction. Such inferences need further research to confirm in the future.

The retrospective design of this study offers several benefits, including a high quality of data and a large number of patients. Our study provides a real-world representation of the current clinical practices for heatstroke in a mixed population of critically ill adult patients treated in ICUs in Sichuan Province, China. The patient sample size provides a robust representation of the target population, increasing the generalizability of our findings. Overall, our study provides important insights into the prevalence of GI symptoms among critically ill heatstroke patients and its relationship with risk factors and clinical outcomes. The findings of this study have important implications for the management and care of critically ill patients with heatstroke. Previous literature has demonstrated the vulnerability of the digestive tract to abnormal conditions, including hypoxia and elevated temperatures[4,12,13,18,19]. Studies have also indicated that most patients experience some form of GI symptoms during intense physical activity and elevated body temperature[20]. Our study on GI symptoms following heatstroke incorporates risk factors and provides a comprehensive understanding of the subject, thereby supplementing previous research.

Nevertheless, this study had some limitations. First, the use of GI symptoms to respond to GI dysfunction is one-sided. Another limitation is the exclusion of the most critically ill patients who had already passed away and those admitted to general wards. While this selection criterion was a necessary aspect of the research program, it is possible that the inclusion of these patients would not have greatly impacted the overall prognosis, as previously discussed. Our study was an observation of symptoms and did not address possible effects of treatment on GI function. Additionally, there is a high rate of missed diagnoses due to a lack of awareness of heatstroke in remote mountainous areas and the inadequate identification of heatstroke in a timely manner.

The incidence of GI symptoms among heatstroke patients admitted to the ICU was reportedly 18.5% in our study. Patients who are older and with a lower GCS score on admission have an increased likelihood of developing GI symptoms. Heatstroke patients with GI symptoms found it more difficult to tolerate EN therapy than did those without. Patients with GI symptoms were found to have a higher incidence of complications. The earlier the GI symptoms appeared and the longer the duration of GI symptoms, the more difficult it was for patients to tolerate EN, and the worse the predicted prognosis.

Extreme heat exposure is a growing health problem. The effects of heat on the gastrointestinal tract is unknown.

It was intended to summarize the effects of heat on the gastrointestinal (GI) tract of intensive care unit (ICU) patients.

This study aimed to assess the incidence of GI symptoms associated with heatstroke and its impact on outcomes.

We conducted a retrospective, multi-center, observational cohort study to analyze outcomes between patients.

The timing and duration of gastrointestinal symptoms affects heatstroke patient's prognosis and enteral nutrition (EN) therapy. The status of EN therapy is related to heatstroke patients’ outcomes. Advanced age and low Glasgow coma scale (GCS) scores are risk factors for gastrointestinal symptoms in heatstroke patients.

The GI manifestations of heatstroke are common and appear to impact clinically relevant hospitalization outcomes.

This was a retrospective, multi-center, observational cohort study that involved patients admitted to 83 ICUs located in 16 cities in the Sichuan Province, China between June 1 and October 31, 2022. Results showed older heatstroke patients with a lower GCS score on admission were more likely to experience GI symptoms, which had statistical difference. Clinicians should pay attention to the time at which heatstroke patients started manifesting gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as the duration of said symptoms, to ensure that patients are timely treated with the proper EN therapy and have the best prognosis possible.

The authors would like to acknowledge all investigators who participated in this trial. A full list of members who participated in this study from the Heatstroke Research Group in Southwest China: Wei Tang (Dazhou Central Hospital), Yi-Song Ren (Chengdu Pidu District Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Qiong-Lan Dong (The Third People's Hospital of Mianyang), Mao-Juan Wang (Deyang People's Hospital), Liang-Hai Cao (Yibin Second People's Hospital), Xian-JunWang (The Second People's Hospital of Jiangyou City), Lang Tu (Shehong People's Hospital), Guang-Hong Ye (Anyue County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine), Li Chen (Guang'an District People's Hospital, Guang'an City), An-Qin Li (The Fourth People's Hospital of Jiangyou City), Zhi-Fu Liu (Jingyan County People's Hospital), Xiao-Lin Han (Pengzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Yu Dai (Mianyang Anzhou District People's Hospital), Xiong Yang (Langzhong People's Hospital), Jun Chen (Jianyang People's Hospital), Xian-Peng Qiu (The Fourth People's Hospital of Zigong City), Sen-Zhong Cheng (Zhongjiang County People's Hospital), Bo Qi (Sichuan Jiangyou 903 Hospital), Pan Yang (Meishan Cancer Hospital), Xu-Ting Deng (Luxian People's Hospital), Qin-Ya Ding (Linshui County Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Chun-Mei Huang (Nanjiang County Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Fang-Pei Zhang (Hejiang County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine), Hong-Yu Yang (Mianyang Fulin Hospital), Xiao-Cui Wang (Deyang Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Medicine), Jia-Jin Li (Mianyang People's Hospital), Xiao-Jiao Liu (Guanghan People's Hospital), Xue-Mei Ye (Meishan People's Hospital), Fang Wu (Ziyang Lezhi County People's Hospital), Tao Ye (Leshan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Zhuo Tang (Zizhong County Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Liang He (Pyeongchang County Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital), Jian Gong (Ziyang People's Hospital), Hong-Xu Chen (Leshan Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital); Qiong-Hua Hu (Mianyang Central Hospital); Zhen Wang (Shifang Second Hospital); Rong Hu (Xingwen County People's Hospital); You-Wei Li (The Third People's Hospital of Anyue County); Lin Hou (Bazhong Enyang District People's Hospital); Zhuo Chen (The Third People's Hospital of Yibin); Hua-Qiang Shen (Bazhong Central Hospital); Jian Wang (Guang'an People's Hospital); Ping Fang (Neijiang Second People's Hospital); Yu Liu (Lezhi County Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital in Sichuan Province); Yan Luo (Luzhou Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital); Wei-Peng Xu (Fushun County People's Hospital); Chun-Lin Zhang (Yibin Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital); Xiao-Qi Tang (Ziyang Yanjiang District People's Hospital); Yu-Liu (Lezhi County People's Hospital); Jing-Mei Yang (Qingshen County People's Hospital); Xin-Pin Yang (Pyeongchang County People's Hospital, Bazhong City); Liang Chen (Gaoxian People's Hospital); Guang-Wei Yang (Huaying People's Hospital); Chun-Hong Tang (Jintang County First People's Hospital); Shi-Hao Ren (Zitong County People's Hospital); Jie Zhao (Ziyang People's Hospital); Pin Li (Shehong Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine); Ya Qiang (Mianyang Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital); Hong-Zhou Wang (Sichuan Science City Hospital); Sen-Zhong Cheng (Sichuan Mianyang 404 Hospital); Song-Lin Wu (Affiliated Hospital of Southwest Medical University); Lu Liu (Luzhou Xuyong County People's Hospital); Xue-Cha Li (Neijiang Dongxing District People's Hospital); Shi-Hu Zhang (Ya'an Yucheng District People's Hospital); He Lin (Zizhong County People's Hospital); Xiao-Dong Feng (Mianzhu People's Hospital); Jun Liang (Zitong County People's Hospital of Mianyang City).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Thongon N, Thailand S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Li L

| 1. | Bouchama A, Abuyassin B, Lehe C, Laitano O, Jay O, O'Connor FG, Leon LR. Classic and exertional heatstroke. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2022;8:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 215] [Article Influence: 71.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Bouchama A, Cafege A, Devol EB, Labdi O, el-Assil K, Seraj M. Ineffectiveness of dantrolene sodium in the treatment of heatstroke. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:176-180. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Pires W, Wanner SP, Soares DD, Coimbra CC. Author's Reply to Kitic: Comment on: "Association Between Exercise-Induced Hyperthermia and Intestinal Permeability: A Systematic Review". Sports Med. 2018;48:2887-2889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Soares AD, Costa KA, Wanner SP, Santos RG, Fernandes SO, Martins FS, Nicoli JR, Coimbra CC, Cardoso VN. Dietary glutamine prevents the loss of intestinal barrier function and attenuates the increase in core body temperature induced by acute heat exposure. Br J Nutr. 2014;112:1601-1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Epstein Y, Yanovich R. Heatstroke. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2449-2459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 190] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 57.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Razzak JA, Agrawal P, Chand Z, Quraishy S, Ghaffar A, Hyder AA. Impact of community education on heat-related health outcomes and heat literacy among low-income communities in Karachi, Pakistan: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Grimaldi D, Legriel S, Pichon N, Colardelle P, Leblanc S, Canouï-Poitrine F, Ben Hadj Salem O, Muller G, de Prost N, Herrmann S, Marque S, Baron A, Sauneuf B, Messika J, Dior M, Creteur J, Bedos JP, Boutin E, Cariou A. Ischemic injury of the upper gastrointestinal tract after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a prospective, multicenter study. Crit Care. 2022;26:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, Du B, Li LJ, Zeng G, Yuen KY, Chen RC, Tang CL, Wang T, Chen PY, Xiang J, Li SY, Wang JL, Liang ZJ, Peng YX, Wei L, Liu Y, Hu YH, Peng P, Wang JM, Liu JY, Chen Z, Li G, Zheng ZJ, Qiu SQ, Luo J, Ye CJ, Zhu SY, Zhong NS; China Medical Treatment Expert Group for Covid-19. Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19202] [Cited by in RCA: 18877] [Article Influence: 3775.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 9. | Mutlu GM, Mutlu EA, Factor P. GI complications in patients receiving mechanical ventilation. Chest. 2001;119:1222-1241. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 226] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Reintam A, Parm P, Kitus R, Kern H, Starkopf J. Gastrointestinal symptoms in intensive care patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2009;53:318-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Spohn SN, Mawe GM. Non-conventional features of peripheral serotonin signalling - the gut and beyond. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:412-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Pires W, Veneroso CE, Wanner SP, Pacheco DAS, Vaz GC, Amorim FT, Tonoli C, Soares DD, Coimbra CC. Association Between Exercise-Induced Hyperthermia and Intestinal Permeability: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2017;47:1389-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Walter E, W Watt P, Gibson OR, Wilmott AGB, Mitchell D, Moreton R, Maxwell NS. Exercise hyperthermia induces greater changes in gastrointestinal permeability than equivalent passive hyperthermia. Physiol Rep. 2021;9:e14945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Leon LR, DuBose DA, Mason CW. Heat stress induces a biphasic thermoregulatory response in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2005;288:R197-R204. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Leon LR, Blaha MD, DuBose DA. Time course of cytokine, corticosterone, and tissue injury responses in mice during heat strain recovery. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2006;100:1400-1409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 117] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Camus G, Deby-Dupont G, Duchateau J, Deby C, Pincemail J, Lamy M. Are similar inflammatory factors involved in strenuous exercise and sepsis? Intensive Care Med. 1994;20:602-610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Garcin JM, Bronstein JA, Cremades S, Courbin P, Cointet F. Acute liver failure is frequent during heat stroke. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:158-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Costa RJS, Snipe RMJ, Kitic CM, Gibson PR. Systematic review: exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome-implications for health and intestinal disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:246-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 266] [Article Influence: 33.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Rowell LB. Human cardiovascular adjustments to exercise and thermal stress. Physiol Rev. 1974;54:75-159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1071] [Cited by in RCA: 1006] [Article Influence: 19.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Graber CD, Reinhold RB, Breman JG, Harley RA, Hennigar GR. Fatal heat stroke. Circulating endotoxin and gram-negative sepsis as complications. JAMA. 1971;216:1195-1196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |