TO THE EDITOR

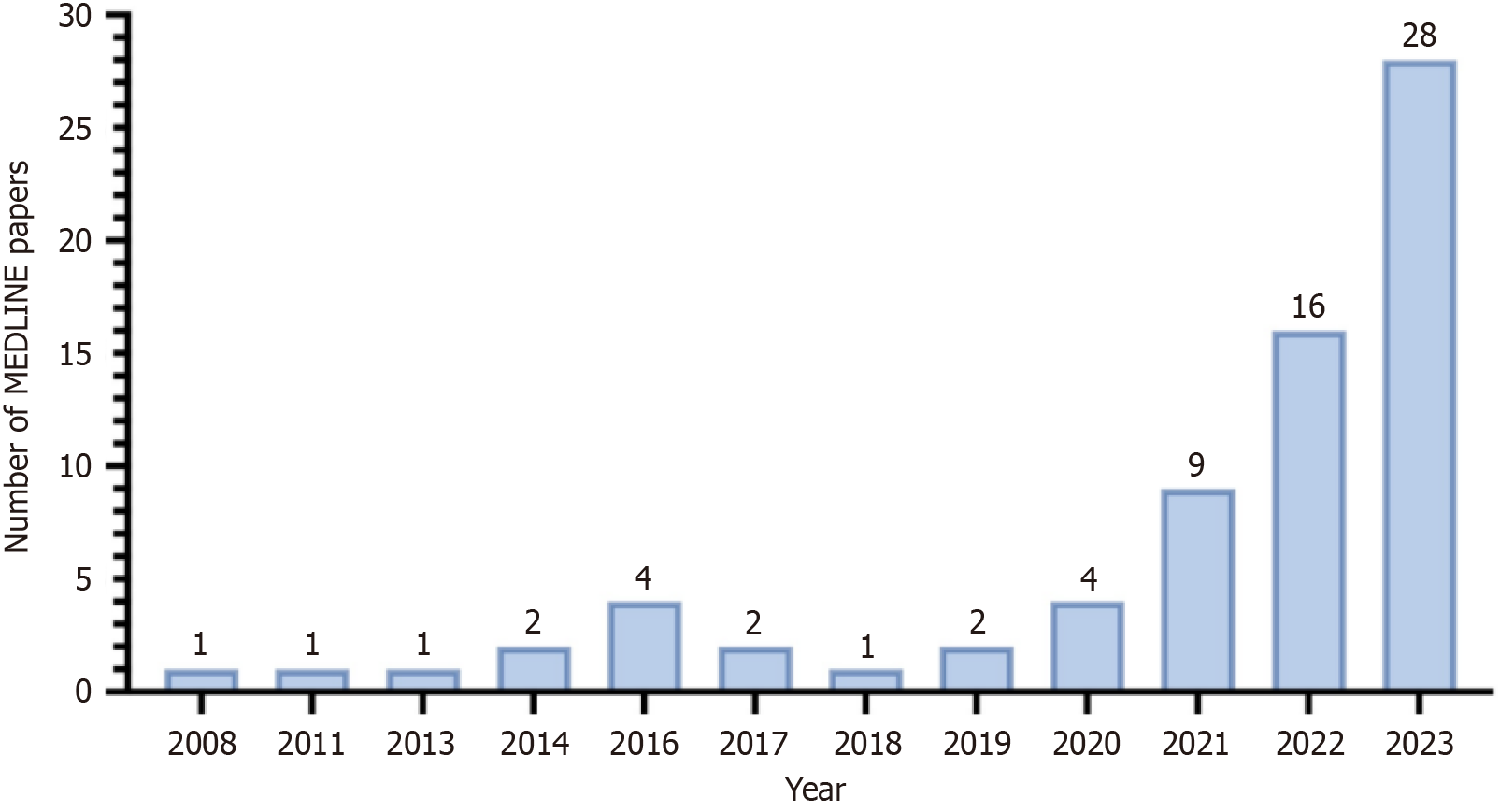

We read with interest an article titled “Hotspots and frontiers of the relationship between gastric cancer and depression: A bibliometric study” by Liu et al[1] and published in the World Journal of Gastroenterology. The paper belongs to a broad class of bibliometric analysis, a type of research review that has experienced a real explosion in recent years concerning gastric cancer (GC). It primarily weighs how particular strands of research evolve and impact the global research environment (Figure 1). This kind of study can help researchers understand areas of research with a greater focus and those in which the international scientific community places more emphasis.

Figure 1 Output curve of the bibliometric analysis of gastric cancer in MEDLINE.

The graph used “bibliometric analysis AND gastric cancer” as search operators on December 17, 2023, without additional filters. As can be seen, from 2008 to the present day, there was an increase in scientific production. The graph was created with GraphPad PRISM.

The authors’ bibliometric study tracked research trends in the relationship between GC and depression. In this analysis, the authors selected papers from the Web of Science Core Collection, thus quickly identifying articles published in high-impact journals. However, including other relevant databases (e.g., Scopus, MEDLINE) and as many high-impact articles, many of which are indexed in Web of Science, would have been desirable to deepen the analysis. The search time window was extensive, potentially covering articles from 2000 until the end of 2022. Given the bidirectionality of GC and depression in epidemiological, clinical, and pathophysiological terms, they preferred to divide the analysis into two large blocks (i.e. GC-to-depression and depression-to-GC).

We strongly agree with the authors on that choice, given the highly intricate relationship between the gastrointestinal tract and the nervous system configuring what has now been repeatedly referred to as the gut-brain axis[2]. We believe the research rationale for this analysis was based on the now-established very high prevalence of mood disorders in patients with GC. The prevalence of depression in GC patients is over 35%, and is the highest in the eastern Mediterranean region (> 40%)[3]. Unfortunately, this issue extends to patients with recurrent GC[4], who account for a specific and relevant proportion of GC patients. GC patients experience several triggers of depression beginning with the tumour diagnosis and continuing through the entire complex diagnostic, staging, and therapeutic pathway that consists of stressful diagnostic examinations, invasive surgical therapies, and medical treatment associated with potential adverse events. These findings reinforce the need to prioritise research trends, especially those that are clinically relevant and likely to impact the reduction of prevalence.

Thanks to the authors’ analysis, we understand how the research trend of GC and depression identified a critical paradigm shift. In detail, from a deterministic approach addressing GC as the cause of the development and progression of depression, a shift to research aimed in the opposite direction, i.e. on the effects of depression on the onset and evolution of the GC has occurred. In the analysis, it is probably no coincidence that most articles in the depression-to-GC block were basic science articles. The mechanistic hypotheses drawn so far seem to include oxidative stress[5] and acceleration of GC metastasis via the beta(2)-AIR/metastasis associated with the colon cancer 1 axis[6]. Especially in chronic cases, there is a close association between diseases of psychiatric and gastrointestinal origins. For example, our research group, has repeatedly seen this in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, recognising worrying levels of anxious-depressive symptoms even in conditions of absolute clinical remission of the digestive pathology[7]. Unfortunately, just as patients with inflammatory bowel disease suffer from chronic gastrointestinal symptoms, those with GC can also experience particularly debilitating and often severe clinical scenarios. These scenarios are often chronic, with weight loss, anorexia, and even continuous vomiting owing to pyloric stenosis or haematemesis associated with ulcerated or bleeding tumours[8]. This reinforces the importance of detecting psychiatric symptoms early in order to avoid experiencing them together with gastrointestinal complications.

Consequently, the problem arises of finding validated instruments to weigh these symptoms early and reliably in order to be able to refer the patient to specialised psychiatric treatment at an early stage. Notably, we find it interesting that the second most cited article in the GC-to-depression analysis block focused directly on a depression scale for the assessment of depressive and anxious symptoms in patients with GC. The study developed a baseline clinical model for prediction of anxious-depressive status at 6 months[9].

Therefore, we consider it especially important for future research to weight questionnaires for the detection of anxiety and depression levels in GC patients. That would make it possible to detect the symptoms early. Many of the questionnaires already used in digestive pathologies have simple scoring methods that can be deciphered even by physicians without psychiatric experience as tools to screen for depressive pathologies to be referred later to a specialist in the field. For example, our research group has experience with the Beck anxiety[10] and depression[11] inventories and has used them in cases of inflammatory bowel disease[12] and irritable bowel syndrome[13]. Others have used these questionnaires in patients with GC[14,15]. Additional discussion of the tools used to diagnose and evaluate depression, especially in the GC-to-depression block, would have been helpful. We therefore consider that as a limitation of the analysis, which could have been more thorough in that regard.

In addition to what the authors have discussed, an important research direction would be to study validated questionnaires for the early detection of depressive symptoms, specifically in patients with GC. If one wants to compare the two major building blocks of this relationship (i.e. depression-to-GC and GC-to-depression), an advantage of including both directions of this vicious cycle would be the early detection of depression. Nonetheless, all previous considerations increasingly lean toward a multidisciplinary approach to GC, which is widely acclaimed and has already been shown to positively impact cancer prognosis[16].

The bibliometric analysis revealed a broad interest in this geographically varied subject. Some regions were found to have a greater propensity for research in this area (i.e. China and Korea). This finding may stimulate research in other geographic regions given the phenotypic variety of depression and its risk factors when considering geographic variations[17].

This bibliometric analysis ultimately found a thriving and growing body of research aimed at achieving a dignified quality of life by GC patients by investigating the relationship with psychiatric comorbidities. In the past 5 years, this field of research has experienced nearly exponential growth, but analysis of these articles and their keywords highlighted a need to develop precise guidelines. That is, a better understanding of the pathophysiological mechanisms that link depression to the onset and influence of the course of GC is needed. It is also desirable to establish what tools are best to decrease depressive disorders in this neoplastic population. One must identify when and how to provide appropriate follow-up. More randomized trials and high-quality studies are needed to test whether the management of depression in such patients also impacts oncologic prognosis and in what manner.