Published online Aug 7, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i29.3465

Revised: April 28, 2024

Accepted: June 18, 2024

Published online: August 7, 2024

Processing time: 169 Days and 16.3 Hours

Early diagnosis is key to prevent bowel damage in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Risk factor analyses linked with delayed diagnosis in European IBD patients are scarce and no data in German IBD patients exists.

To identify risk factors leading to prolonged diagnostic time in a German IBD cohort.

Between 2012 and 2022, 430 IBD patients from four Berlin hospitals were enrolled in a prospective study and asked to complete a 16-item questionnaire to determine features of the path leading to IBD diagnosis. Total diagnostic time was defined as the time from symptom onset to consulting a physician (patient waiting time) and from first consultation to IBD diagnosis (physician diagnostic time). Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify risk factors for each time period.

The total diagnostic time was significantly longer in Crohn’s disease (CD) compared to ulcerative colitis (UC) patients (12.0 vs 4.0 mo; P < 0.001), mainly due to increased physician diagnostic time (5.5 vs 1.0 mo; P < 0.001). In a multivariate analysis, the predominant symptoms diarrhea (P = 0.012) and skin lesions (P = 0.028) as well as performed gastroscopy (P = 0.042) were associated with longer physician diagnostic time in CD patients. In UC, fever was correlated (P = 0.020) with shorter physician diagnostic time, while fatigue (P = 0.011) and positive family history (P = 0.046) were correlated with longer physician diagnostic time.

We demonstrated that CD patients compared to UC are at risk of long diagnostic delay. Future efforts should focus on shortening the diagnostic delay for a better outcome in these patients.

Core tip: Early diagnosis is key to reducing complications and improving response to medical therapy. This prospective questionnaire-based study aimed to identify risk factors impairing diagnostic time. We demonstrated that diagnostic delay was significantly longer in Crohn’s disease than in ulcerative colitis and was mainly physician dependent. The multivariate analysis showed that disease-specific symptoms and rapidly available diagnostic tools resulted in reduction of physician diagnostic time.

- Citation: Blüthner E, Dehe A, Büning C, Siegmund B, Prager M, Maul J, Krannich A, Preiß J, Wiedenmann B, Rieder F, Khedraki R, Tacke F, Sturm A, Schirbel A. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel diseases in a German population. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(29): 3465-3478

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i29/3465.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i29.3465

Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the most common forms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). IBD is defined as destructive inflammatory disorder of the gastrointestinal tract resulting in chronic relapsing–remitting disease courses. IBD manifests primarily in the intestine but may also have extraintestinal manifestation (EIM). IBD has been shown to be associated with various autoimmune diseases that impact other organs or systems[1,2]. Due to its heterogeneous, nonspecific clinical presentation, and poor diagnostic precision of existing biomarker tests, diagnosis of IBD can be challenging and often results in a prolonged time from symptom onset to an established and correct diagnosis[3,4]. The median delay in diagnosis ranges from 5.0 to 9.5 months for CD and 3.1 to 4.0 months for UC, likely due to different medical standards and regional differences in disease behavior[4-7].

However, prompt diagnosis and treatment of these patients is critical. Recently published studies showed that early therapeutic intervention reduced the need for surgery, as well as severe disease progression with complications[5,8]. Early intensive treatment has been associated with improved responses to immunomodulators or targeted biologic therapy[9]. Diagnostic delay affects patients' quality of life and the burden on the healthcare system[10]. Therefore, awareness of risk factors for delayed diagnosis in IBD patients is imperative.

It is noteworthy that most of the studies have evaluated the total diagnostic delay, whereas studies that systematically evaluate the time patients spend before consulting a physician as well as the time the physician takes to establish an IBD diagnosis separately are scarce[4,11]. Most of the studies were performed in countries with different medical provider systems and hence lack generalizability. Results from Central Europe are lacking [4,6,8,11,12]. Considering the east–west gradient in the incidence of IBD, more research is required on this clinical problem[13]. Therefore, we aimed to comprehensively assess risk factors for delayed diagnosis in a German IBD cohort to enhance our management of IBD patients.

From May 2012 to May 2022, 513 patients with IBD were enrolled in this descriptive cross-sectional, questionnaire-based evaluation study at the IBD outpatient clinic.

The patients were recruited at the three hospital sites at the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin (42.3% at Charité-Campus Mitte, 28.4% at Charité-Virchow Klinikum, 26.0% at Charité-Benjamin Franklin) and at Krankenhaus Waldfriede Berlin-Zehlendorf (18%). We included adult patients (no upper age limit) with confirmed CD or UC diagnosis for at least 6 months with completed questionaries and excluded patients who were unable to consent due to mental incapacity or language barriers as well as the diagnosis of indeterminate colitis. Study participants were interviewed once after written informed consent was obtained. A total of 430 patients were enrolled in the study. Fifty-four patients did not complete the questionnaire, 15 were excluded because of a diagnosis of indeterminate colitis, three were excluded because of a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), four did not sign the informed consent form correctly, and sevens were ex

The study was approved by the local ethics committee (EA2/170/11) and was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 and its latest revision of 2013. The study protocol is also compliant with the STROBE criteria[14].

The administered questionnaire contained 16 questions that investigated demographic and disease-specific factors, which may directly or indirectly play a role for the delay of diagnosis. In addition to patient age and gender, urban or rural residence, medical history (predominant symptoms and general symptoms at diagnosis), severity of symptoms, location of disease, method of IBD diagnosis, and whether the patient had affected family members or had ever heard of IBD, were recorded. EIMs were defined as the presence of ankylosing spondylitis, aphthous stomatitis, erythema nodosum, peripheral arthritis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, psoriasis, pyoderma gangrenosum, or uveitis. Medication was categorized as basic (rectal treatment, mesalazine, budesonide) or advanced (cortisone, azathioprine, methotrexate, infliximab, adalimumab).

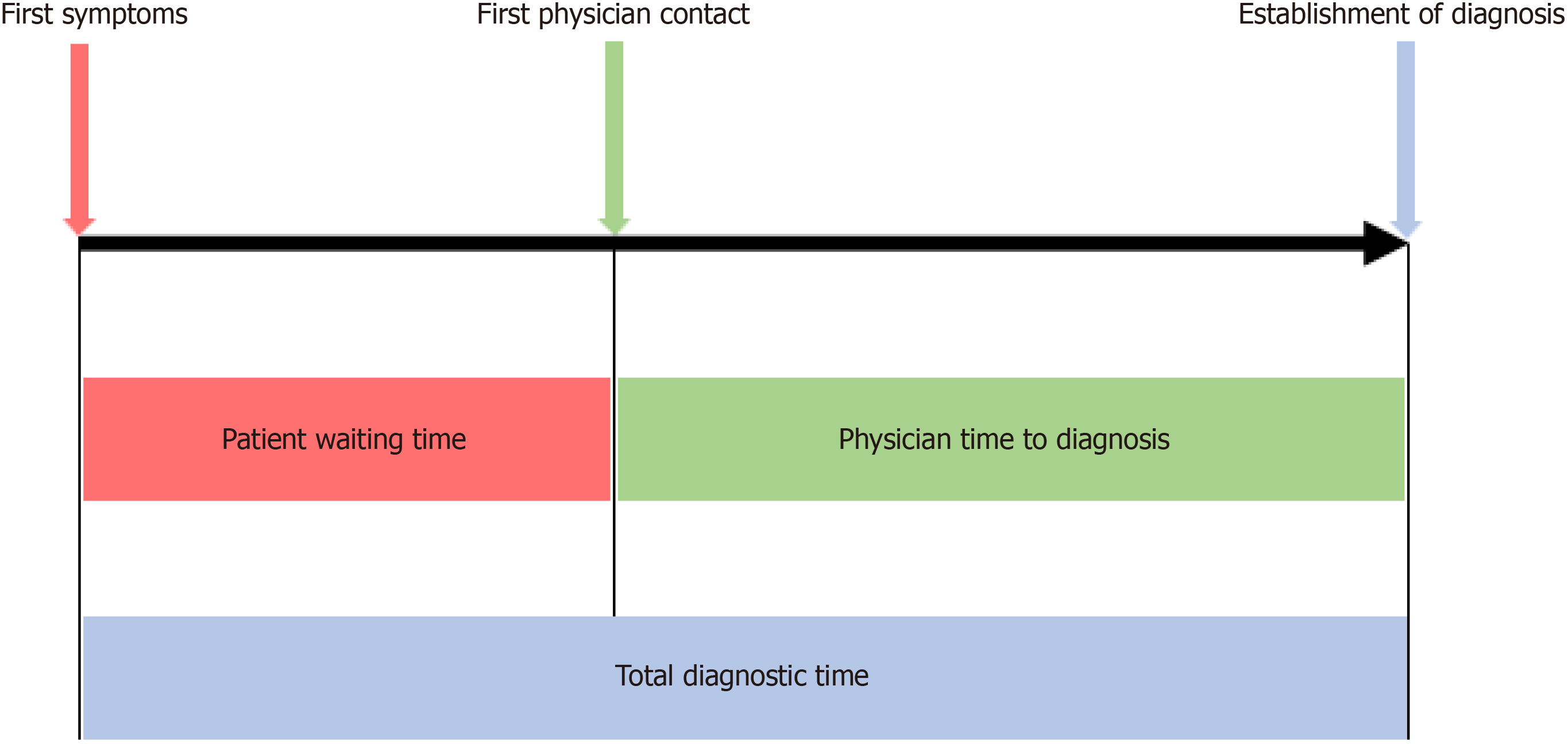

Three different time intervals were assessed in patient questionnaires (Figure 1). Patient waiting time was defined as time from onset of symptoms to first physician contact. Physician time to diagnosis was defined as time from first phy

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS Statistics 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Figures were created using Prism 6 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). We used the Kolmogorov–Smirnoff test to determine the distribution of our data. Continuous variables were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR), differences were compared by the Kruskal–Wallis test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were expressed in the form of numbers and percentages and were compared by the χ2 test. Univariate analysis of the different clinically relevant factors associated with diagnostic time was performed using the Kaplan–Meier survival method and the differences were compared using the log-rank test. We also presented hazard ratios (HR) for the univariate analysis. HRs exceeding unity (HR > 1) represented a better chance for early diagnosis. All variables with a P < 0.1 in univariate analysis were further used for multivariate analyses using Cox’s proportional hazard model in a backward stepwise manner. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Patient characteristics for IBD are summarized in Table 1. We analyzed 223 patients with CD and 207 with UC. Patients were mainly female (54.4%) with a median age at diagnosis of 26 (20–25) years for CD and 28 (21–39) years for UC. The most common reported symptoms were diarrhea in CD (43.5%) and UC (48.8%), followed by abdominal pain in CD (33.2%) and blood in the stool in UC (33.8%). The predominant site of disease at the time of diagnosis was the terminal ileum in CD (68.6%) and the colon in UC (74.4%). Most UC and CD patients were diagnosed based on colonoscopy (78.5 vs 96.1%; P < 0.001) compared with computed tomography (3.1 vs 0.5%; P = 0.037) or magnetic resonance imaging (2.2 vs 0.5 %; P = 0.028). The CD diagnosis was mainly made in hospital (46.6% CD vs 35.5% UC). UC diagnosis was predominantly made by private practice gastroenterologists (38.1% CD vs 46.9% UC). The CD patients reported more severe symptoms compared with UC patients (33.6% CD vs 23.7% UC; P = 0.023) and had more EIMs (26.0% CD vs 12.1% UC; P < 0.001).

| Parameter | CD (n = 223) | UC (n = 207) | P value |

| Sex, M/F | 95/128 | 101/106 | 0.198 |

| Age at enrolment (yr) | 40 (30-50) | 41 (32-52) | 0.509 |

| Age at diagnosis (yr) | 26 (20-35) | 28 (21-39) | 0.565 |

| Residence at diagnosis | 0.554 | ||

| Village | 12 (5.4) | 14 (6.8) | 0.537 |

| Small-town | 18 (8.1) | 18 (8.7) | 0.801 |

| Medium-sized town | 24 (10.8) | 14 (6.8) | 0.149 |

| Large city | 165 (74.0) | 152 (73.9) | 0.977 |

| Abroad | 1 (0.4) | 5 (2.4) | 0.081 |

| Patient waiting time (mo) | 2.0 (0.5-6.0) | 1.0 (0.5-4.0) | 0.051 |

| Physician time to diagnosis (mo) | 5.5 (0.75-23.5) | 1.0 (0-5.0) | < 0.001 |

| Total diagnostic time (mo) | 12.0 (6.0-24.0) | 4.0 (1.5-12.0) | < 0.001 |

| Predominant symptom | |||

| Diarrhea | 97 (43.5) | 101 (48.8) | 0.239 |

| Constipation | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.954 |

| Abdominal pain | 74 (33.2) | 16 (7.7) | < 0.001 |

| Heartburn | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.336 |

| Bloating | 0 (0) | 3 (1.4) | 0.070 |

| Blood in stool | 11 (4.9) | 70 (33.8) | < 0.001 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 9 (4.0) | 0 (0) | 0.004 |

| Skin | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.954 |

| Joint pain | 4 (1.8) | 0 (0) | 0.054 |

| Fistula | 5 (2.2) | 0 (0) | 0.031 |

| Weight loss | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.336 |

| Fever | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.5) | 0.954 |

| Fatigue | 5 (2.2) | 5 (2.4) | 0.897 |

| Other symptoms | 8 (3.6) | 3 (1.4) | 0.164 |

| Location | |||

| Upper GI | 19 (8.5) | 2 (1.0) | < 0.001 |

| Small bowel | 73 (32.7) | 16 (7.7) | < 0.001 |

| Terminal ileum | 153 (68.6) | 21 (10.1) | < 0.001 |

| Colon | 101 (45.3) | 154 (74.4) | < 0.001 |

| Rectum | 49 (22.0) | 111 (53.6) | < 0.001 |

| Severity | |||

| Very mild | 7 (3.1) | 9 (4.3) | 0.519 |

| Mild | 11 (4.9) | 23 (11.1) | 0.019 |

| Moderate | 38 (17.0) | 55 (26.6) | 0.018 |

| Strong | 88 (39.5) | 69 (33.3) | 0.187 |

| Very strong | 75 (33.6) | 49 (23.7) | 0.023 |

| Physician | |||

| Gastroenterologist | 85 (38.1) | 97 (46.9) | 0.066 |

| Hospital | 104 (46.6) | 73 (35.3) | 0.017 |

| General practitioner | 18 (8.1) | 19 (9.2) | 0.682 |

| Expert in IBD | 9 (4.0) | 9 (4.3) | 0.871 |

| Another consultant | 4 (1.8) | 8 (3.9) | 0.187 |

| Others | 2 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) | 0.172 |

| Diagnostic tests | |||

| Colonoscopy | 175 (78.5) | 199 (96.1) | < 0.001 |

| Gastroscopy | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.111 |

| Sonography | 4 (1.8) | 1 (0.5) | 0.193 |

| Computed tomography | 7 (3.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.037 |

| Magnetic resonance imaging | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.5) | 0.028 |

| Diagnosis change | 23 (10.3) | 35 (16.9) | 0.070 |

| Positive family history | 35 (15.7) | 35 (16.9) | 0.808 |

| Parents | 13 (37.1) | 10 (28.6) | 0.445 |

| Siblings | 12 (5.4) | 8 (22.9) | 0.290 |

| Aunt/uncle | 2 (0.9) | 8 (22.9) | 0.040 |

| Grandparents | 4 (1.8) | 9 (25.7) | 0.124 |

| Knowledge of IBD | 49 (22.0) | 39 (18.8) | 0.437 |

| Affected person | 27 (55.1) | 20 (51.3) | 0.721 |

| Media | 10 (20.4) | 7 (17.9) | 0.772 |

| Internet | 8 (16.3) | 6 (15.4) | 0.904 |

| Profession | 6 (12.2) | 9 (23.1) | 0.179 |

| Medication | |||

| Mesalazine | 149 (66.8) | 180 (87.0) | < 0.001 |

| Budesonide | 68 (30.5) | 24 (11.6) | < 0.001 |

| Cortisone | 54 (24.2) | 115 (55.6) | < 0.001 |

| Azathioprine | 2 (0.9) | 29 (14.0) | 0.007 |

| Methotrexate | 7 (3.1) | 1 (0.5) | 0.607 |

| Infliximab | 7 (3.1) | 5 (2.4) | 0.649 |

| Adalimumab | 17 (7.6) | 1 (0.5) | 0.042 |

| Local treatment | 13 (5.8) | 64 (30.9) | < 0.001 |

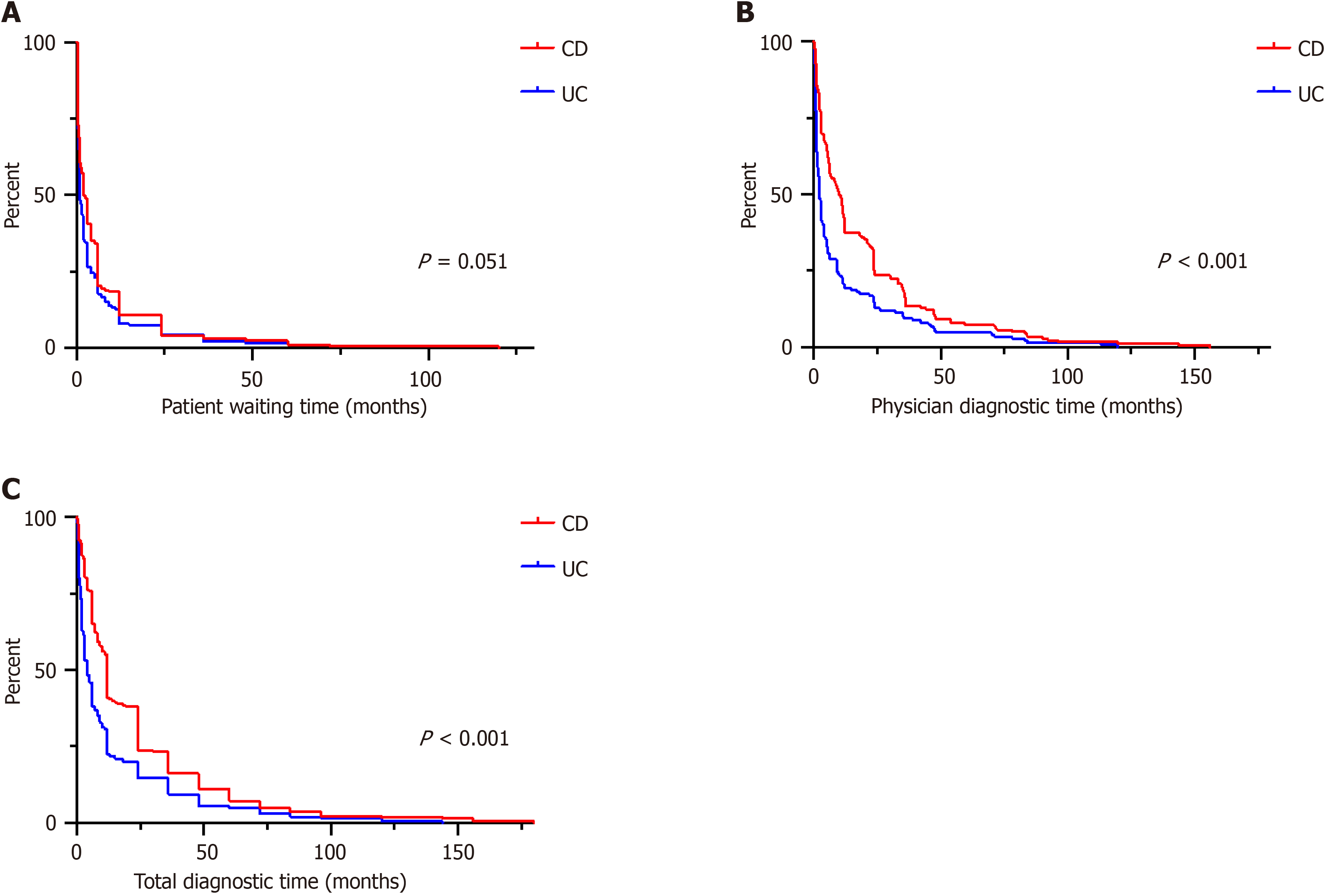

Total diagnostic time was longer for CD (12.0 months; IQR 6.0–24.0) than UC (4.0 months; IQR 1.5–12.0; P < 0.001). While the patient waiting time was comparable between CD and UC (2.0 months; IQR 0.5–6.0) vs 1.0 month; IQR 0.5–4.0; P = 0.051), the physician diagnostic time was longer in CD patients (5.5 months; IQR 0.75–23.5) than UC patients (1.0 month; IQR 0–5.0; P < 0.001). Time to event analysis for all three intervals for CD and UC, separately, are depicted as Kap

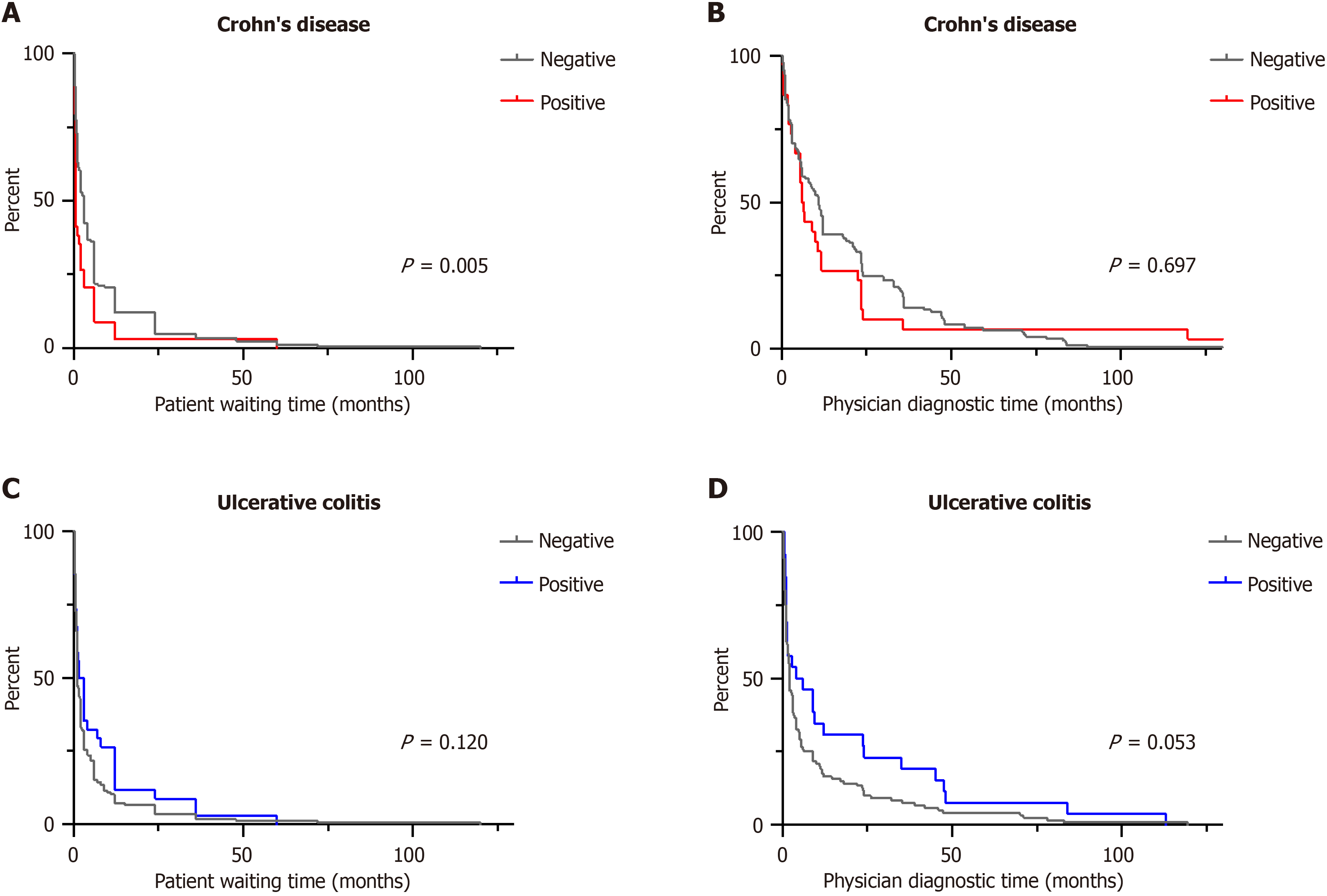

Patient waiting time: In the univariate analysis, patient waiting time was shorter with female sex (P = 0.089), living abroad (P = 0.020), the predominant symptoms of abdominal pain (P = 0.038), fistula (P = 0.032), nausea/vomiting (P = 0.075), strong disease severity (P = 0.023), and positive family history of IBD (P = 0.005). Longer patient waiting time was associated with blood in stool (P = 0.069) and diarrhea (P < 0.001). The clinical factors influencing patient waiting time in CD are summarized in Table 2.

| Parameter | Patient waiting time | Physician diagnostic time | |||

| HR | P value | HR | P value | ||

| Sex, female vs male | CD | 1.235 | 0.089 | 0.852 | 0.222 |

| UC | 0.954 | 0.714 | 0.897 | 0.407 | |

| Age, ≤ 40 vs > 40 yr | CD | 1.071 | 0.654 | 1.176 | 0.329 |

| UC | 1.407 | 0.031 | 1.109 | 0.508 | |

| Year of diagnosis, ≤ 2000 vs > 2000 | CD | 1.081 | 0.520 | 0.975 | 0.846 |

| UC | 0.947 | 0.666 | 0.976 | 0.856 | |

| Predominant symptom | |||||

| Diarrhea, yes vs no | CD | 0.826 | 0.116 | 1.484 | 0.003 |

| UC | 1.141 | 0.305 | 1.065 | 0.640 | |

| Constipation, yes vs no | CD | 2.045 | 0.440 | 1.835 | 0.517 |

| UC | 1.011 | 0.991 | 0.882 | 0.893 | |

| Abdominal pain, yes vs no | CD | 1.307 | 0.038 | 0.834 | 0.191 |

| UC | 1.096 | 0.701 | 0.708 | 0.167 | |

| Heartburn, yes vs no | CD | 0.975 | 0.979 | 0.826 | 0.844 |

| Bloating, yes vs no | UC | 0.218 | 0.010 | 0.789 | 0.664 |

| Blood in stool, yes vs no | CD | 0.609 | 0.069 | 1.272 | 0.419 |

| UC | 1.014 | 0.916 | 0.999 | 0.993 | |

| Nausea/vomiting, yes vs no | CD | 1.216 | 0.520 | 0.675 | 0.233 |

| Skin, yes vs no | CD | 1.164 | 0.872 | 5.178 | 0.044 |

| UC | 0.295 | 0.138 | 3.637 | 0.108 | |

| Joint pain, yes vs no | CD | 0.844 | 0.703 | 0.323 | 0.039 |

| Fistula, yes vs no | CD | 2.450 | 0.032 | 0.656 | 0.334 |

| Weight loss, yes vs no | CD | 0.387 | 0.236 | 5.178 | 0.044 |

| Fever, yes vs no | CD | 0.387 | 0.236 | 0.620 | 0.619 |

| UC | 6.191 | 0.026 | 1.207 | 0.838 | |

| Fatigue, yes vs no | CD | 1.482 | 0.335 | 1.452 | 0.390 |

| UC | 1.652 | 0.225 | 1.937 | 0.101 | |

| Symptoms | |||||

| Diarrhea, yes vs no | CD | 0.590 | < 0.001 | 0.947 | 0.732 |

| UC | 1.331 | 0.068 | 1.028 | 0.867 | |

| Constipation, yes vs no | CD | 1.103 | 0.644 | 0.747 | 0.209 |

| UC | 1.031 | 0.921 | 0.808 | 0.513 | |

| Abdominal pain, yes vs no | CD | 0.988 | 0.934 | 0.963 | 0.812 |

| UC | 1.018 | 0.889 | 0.952 | 0.708 | |

| Heartburn, yes vs no | CD | 0.988 | 0.947 | 0.735 | 0.110 |

| UC | 0.697 | 0.140 | 1.014 | 0.955 | |

| Bloating, yes vs no | CD | 0.827 | 0.150 | 0.842 | 0.235 |

| UC | 0.814 | 0.132 | 0.960 | 0.770 | |

| Blood in stool, yes vs no | CD | 0.932 | 0.572 | 0.889 | 0.393 |

| UC | 0.970 | 0.856 | 0.913 | 0.586 | |

| Nausea/vomiting, yes vs no | CD | 1.264 | 0.075 | 1.082 | 0.574 |

| UC | 1.210 | 0.334 | 0.966 | 0.864 | |

| Skin, yes vs no | CD | 0.801 | 0.261 | 0.628 | 0.036 |

| UC | 0.663 | 0.157 | 0.947 | 0.859 | |

| Joint pain, yes vs no | CD | 0.882 | 0.403 | 0.733 | 0.066 |

| UC | 0.780 | 0.309 | 0.836 | 0.478 | |

| Fistula, yes vs no | CD | 1.280 | 0.231 | 0.937 | 0.770 |

| UC | 0.694 | 0.421 | 0.766 | 0.574 | |

| Weight loss, yes vs no | CD | 1.019 | 0.875 | 0.900 | 0.416 |

| UC | 1.400 | 0.016 | 0.893 | 0.429 | |

| Fever, yes vs no | CD | 1.196 | 0.239 | 1.142 | 0.420 |

| UC | 1.381 | 0.150 | 1.654 | 0.026 | |

| Fatigue, yes vs no | CD | 1.094 | 0.457 | 0.959 | 0.746 |

| UC | 0.961 | 0.757 | 0.767 | 0.045 | |

| EIM, yes vs no | CD | 0.902 | 0.450 | 0.784 | 0.104 |

| UC | 0.745 | 0.129 | 0.913 | 0.651 | |

| Location | |||||

| Upper GI, yes vs no | CD | 1.198 | 0.400 | 1.256 | 0.323 |

| UC | 0.813 | 0.748 | 0.668 | 0.545 | |

| Small bowel, yes vs no | CD | 0.910 | 0.461 | 0.929 | 0.594 |

| UC | 1.007 | 0.976 | 0.818 | 0.411 | |

| Terminal ileum, yes vs no | CD | 0.964 | 0.778 | 1.183 | 0.237 |

| UC | 0.849 | 0.432 | 1.087 | 0.700 | |

| Colon, yes vs no | CD | 1.135 | 0.292 | 0.927 | 0.565 |

| UC | 1.014 | 0.924 | 1.012 | 0.934 | |

| Rectum, yes vs no | CD | 1.075 | 0.616 | 1.043 | 0.791 |

| UC | 0.864 | 0.251 | 0.907 | 0.457 | |

| Disease severity, strong vs mild | CD | 1.359 | 0.023 | 1.240 | 0.154 |

| UC | 1.098 | 0.469 | 1.247 | 0.096 | |

| Diagnosis made in hospital, yes vs no | CD | 0.915 | 0.464 | 0.992 | 0.952 |

| UC | 1.314 | 0.039 | 1.013 | 0.923 | |

| Diagnosis made by gastroscopy, yes vs no | CD | 1.059 | 0.891 | 2.857 | 0.011 |

| UC | 1.520 | 0.644 | 0.804 | 0.815 | |

| Family history, positive vs negative | CD | 1.587 | 0.005 | 1.073 | 0.697 |

| UC | 0.767 | 0.120 | 0.708 | 0.053 | |

| Medication, strong vs mild | CD | 1.067 | 0.647 | 0.965 | 0.816 |

| UC | 0.967 | 0.794 | 0.991 | 0.944 | |

Multivariate analysis determined the predominant symptoms of abdominal pain (HR 1.428; P = 0.018), fistula (HR = 2.841; P = 0.027) and positive family history (HR = 1.734; P = 0.004) were associated with shorter patient waiting time (Table 3).

Physician diagnostic time: Univariate analysis of physician diagnostic time revealed that the predominant symptoms of diarrhea (P = 0.003), skin lesions (P = 0.044), joint pain (P = 0.066), and weight loss (P = 0.044), as well as the common symptoms of skin lesions (P = 0.036), joint pain (P = 0.066), and performance of diagnostic gastroscopy (P = 0.011) were linked with shorter physician diagnostic time. The univariate analysis of risk factors for physician diagnostic time are presented in Table 2.

The predominant symptoms of diarrhea (HR = 1.438, P = 0.012), skin lesions (HR = 9.746, P = 0.028), and performance of diagnostic gastroscopy (HR = 2.570, P = 0.042) were associated with shorter physician diagnostic time in the multivariate analysis (Table 4).

Total diagnostic time: In patients with CD, total diagnostic time was longer with the symptom of joint pain (HR = 0.696, P = 0.048) and shorter with performance of diagnostic gastroscopy (HR = 3.019, P = 0.018; data not shown). Location of disease, place of residence at time of diagnosis or year of diagnosis (≤ 2000 vs > 2000) had no effect on the three relevant time intervals shown in Table 2 and were therefore not included in the multivariate model.

Patient waiting time: Univariate analysis of UC patients showed that age ≤ 40 years (P = 0.031), predominant symptoms of fever (P = 0.026), diarrhea (P = 0.068) and weight loss (P = 0.016), and diagnosis made in a hospital setting (P = 0.039) were associated with shorter patient waiting time. The predominant symptom of bloating (P = 0.010) was associated with longer patient waiting time.

In the multivariate analysis, the predominant symptom of bloating was associated with longer patient waiting time (HR = 0.207; P = 0.029), whereas diarrhea was associated with shorter patient waiting time (HR = 1.463, P = 0.034) (Table 5).

| Parameter | Patient waiting time | ||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Bloating1 | 0.207 | 0.050-0.848 | 0.029 |

| Diarrhea | 1.463 | 1.030-2.079 | 0.034 |

Physician diagnostic time: In UC, fever (P = 0.026), fatigue (P = 0.045), strong disease severity (P = 0.096) and negative family history of IBD (P = 0.053) were associated with shorter physician diagnostic time (Table 2). In the multivariate analysis, fever was associated with shorter physician diagnostic time (HR = 1.813; P = 0.020) and fatigue (HR = 0.685; P = 0.011) was associated with longer physician diagnostic time. Surprisingly, a positive family history for IBD (HR = 0.681; P = 0.046) was also associated with longer physician diagnostic time (Table 6).

| Parameter | Physician diagnostic time | ||

| HR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Fatigue | 0.685 | 0.512-0.917 | 0.011 |

| Fever | 1.813 | 1.096-2.999 | 0.020 |

| Positive family history | 0.681 | 0.466-0.994 | 0.046 |

Total diagnostic time: On multivariate analysis, fever was associated with shorter total diagnostic time (HR = 0.743, P = 0.032) and the predominant symptom of fatigue with longer total diagnostic time (HR = 0.285, P = 0.007; data not shown). Location of disease, place of residence at diagnosis, or year of diagnosis were not linked with any of the three diagnostic intervals.

This is the first study in an adult German IBD population to evaluate diagnostic delay, which in addition provides further focus on patient-related and physician-related risk factors. We confirmed the previous observations of markedly longer total diagnostic time in CD patients, which in our study was shown to be mainly physician related[4,5,8]. Disease-specific symptoms and easily available diagnostics led to a reduction in physician diagnostic time. A positive family history de

The IBD incidence has markedly increased worldwide over the last several decades[15,16]. However, regional diffe

In our German CD patients, the total diagnostic time was on average 12 months, which was longer in UC with only 4 months (Figure 2C). This finding is consistent with previously published data regarding diagnostic time in CD versus UC patients. Cantoro et al[18] reported a median diagnostic time of 7.1 vs 2.0 months in Italian patients, Vavricka et al[6] reported 9 versus 4 months in Swiss patients, and Nguyen et al[5] described 9.5 versus 3.1 months in American patients. This marked difference between CD and UC could be attributed to a higher frequency of nonspecific symptoms, such as abdominal pain, in CD compared with UC.

Studies that systematically evaluate the reasons for diagnostic delay are scarce. In this study we also differentiated between patient-related and physician-related causes for the delay. Of note, the diagnostic delay in CD patients was mainly attributed to increased physician diagnostic delay (5.5 months in CD vs 1.0 month in UC). In UC patients, the patient-related time interval was almost equal to the physician-related time interval (2.0 months vs 1.0 month). This finding compares favorably with the previously reported data[5]. One explanation is the marked symptom variance of patients with CD compared to patients with UC, with a large symptom overlap between IBD and functional disease complaints. In our study, nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain or nausea/vomiting were increased in CD (Table 1). CD patients were 2.2 times more likely than UC patients to have an EIM of IBD at the time of disease onset. The effect of atypical versus typical IBD symptoms on time to diagnosis is again demonstrated by the time interval to physician diagnosis. In our study, the presence of prolonged diarrhea and skin manifestations was independently associated with early physician diagnosis in CD patients (Table 3). High symptom severity was linked with faster dia

In the context of diagnostic delay in CD patients, the impact of a positive family history should also be noted. Sur

As therapies continue to advance and the incidence of IBD has steadily increased in recent years, IBD continues to gain more attention[13]. Despite these advances, recent studies have shown no change in time to diagnosis over the past few decades[18]. In line with these data, we discovered that the total diagnostic time in CD and UC has not changed between 1964 to 2021. It is clear, that clinicians’ lack of knowledge and patients’access to specialists including dedicated diagn

Firstly, we want to emphasize the importance of screening tools in primary care. Clinical routine is increasingly determined by time constraints and expanding knowledge about rare diseases. The “Red Flags Index for Suspected CD” by Danese et al[21] has established method of diagnostic accuracy to discriminate healthy controls from IBS and early CD. Easily accessible tools, such as the 8-item questionnaire (CalproQuest) can help to identify potential IBD patients[20]. Questions for perianal fistula, first-degree relatives, weight loss, chronic abdominal pain (not after meals), nocturnal diarrhea, mild fever and rectal urgency can help to screen patients for IBD, especially CD. Implementation of these sc

Secondly, educational programs for general practitioners should specifically target early symptoms, signs, and characteristics of IBD with difficult-to-predict courses, and diverse complications. The respective practitioner level of knowledge about disease symptoms as well as the diagnostic workup are important factors regarding disease identification.

Thirdly, public awareness programs and patient educational training focusing on disease heredity, empower patients to become active participants in a patient-centered care model. Additionally, direct access to specialist appointments for patients may also be helpful to reduce the diagnostic delay. Utilizing these tools can improve patients' quality of life, di

Our study had several limitations. This study focused on the course of IBD diagnosis and did not include well-known disease-modifying factors such as smoking habits or educational level. We did not include disease-related complications, but recognize the influence and relevance they may have on disease outcome. In our analysis we could not find a sig

Despite these limitations, we present in the first German adult IBD cohort that CD patients, more than UC patients, are at risk of a long diagnostic delay, which is mainly physician dependent. Disease-specific symptoms and readily available diagnostics resulted in a reduction in physician diagnostic time. We conclude that good interdisciplinary collaboration, physicians’ awareness, and screening tools are imperative to reduce diagnostic delay and therefore improve treatment starting position, course of disease and patient satisfaction.

We thank all the patients who participated in this study. The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

| 1. | de Souza HSP, Fiocchi C, Iliopoulos D. The IBD interactome: an integrated view of aetiology, pathogenesis and therapy. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14:739-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 39.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chang JT. Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2652-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 274] [Cited by in RCA: 738] [Article Influence: 147.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton LJ, Mulvihill C, Wiltgen C, Zinsmeister AR. Diagnostic value of the Manning criteria in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1990;31:77-81. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nahon S, Lahmek P, Lesgourgues B, Poupardin C, Chaussade S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Abitbol V. Diagnostic delay in a French cohort of Crohn's disease patients. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:964-969. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nguyen VQ, Jiang D, Hoffman SN, Guntaka S, Mays JL, Wang A, Gomes J, Sorrentino D. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Associated Factors on Clinical Outcomes in a U.S. Inflammatory Bowel Disease Cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1825-1831. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vavricka SR, Spigaglia SM, Rogler G, Pittet V, Michetti P, Felley C, Mottet C, Braegger CP, Rogler D, Straumann A, Bauerfeind P, Fried M, Schoepfer AM; Swiss IBD Cohort Study Group. Systematic evaluation of risk factors for diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:496-505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schoepfer AM, Dehlavi MA, Fournier N, Safroneeva E, Straumann A, Pittet V, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Michetti P, Rogler G, Vavricka SR; IBD Cohort Study Group. Diagnostic delay in Crohn's disease is associated with a complicated disease course and increased operation rate. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1744-53; quiz 1754. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 168] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zaharie R, Tantau A, Zaharie F, Tantau M, Gheorghe L, Gheorghe C, Gologan S, Cijevschi C, Trifan A, Dobru D, Goldis A, Constantinescu G, Iacob R, Diculescu M; IBDPROSPECT Study Group. Diagnostic Delay in Romanian Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Risk Factors and Impact on the Disease Course and Need for Surgery. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:306-314. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | D'Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, Tuynman H, De Vos M, van Deventer S, Stitt L, Donner A, Vermeire S, Van De Mierop FJ, Coche JR, van der Woude J, Ochsenkühn T, van Bodegraven AA, Van Hootegem PP, Lambrecht GL, Mana F, Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Hommes D; Belgian Inflammatory Bowel Disease Research Group; North-Holland Gut Club. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 922] [Cited by in RCA: 935] [Article Influence: 55.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | De Boer AG, Bennebroek Evertsz' F, Stokkers PC, Bockting CL, Sanderman R, Hommes DW, Sprangers MA, Frings-Dresen MH. Employment status, difficulties at work and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:1130-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moon CM, Jung SA, Kim SE, Song HJ, Jung Y, Ye BD, Cheon JH, Kim YS, Kim YH, Kim JS, Han DS; CONNECT study group. Clinical Factors and Disease Course Related to Diagnostic Delay in Korean Crohn's Disease Patients: Results from the CONNECT Study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0144390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Li Y, Ren J, Wang G, Gu G, Wu X, Ren H, Hong Z, Hu D, Wu Q, Li G, Liu S, Anjum N, Li J. Diagnostic delay in Crohn's disease is associated with increased rate of abdominal surgery: A retrospective study in Chinese patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47:544-548. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Burisch J, Pedersen N, Čuković-Čavka S, Brinar M, Kaimakliotis I, Duricova D, Shonová O, Vind I, Avnstrøm S, Thorsgaard N, Andersen V, Krabbe S, Dahlerup JF, Salupere R, Nielsen KR, Olsen J, Manninen P, Collin P, Tsianos EV, Katsanos KH, Ladefoged K, Lakatos L, Björnsson E, Ragnarsson G, Bailey Y, Odes S, Schwartz D, Martinato M, Lupinacci G, Milla M, De Padova A, D'Incà R, Beltrami M, Kupcinskas L, Kiudelis G, Turcan S, Tighineanu O, Mihu I, Magro F, Barros LF, Goldis A, Lazar D, Belousova E, Nikulina I, Hernandez V, Martinez-Ares D, Almer S, Zhulina Y, Halfvarson J, Arebi N, Sebastian S, Lakatos PL, Langholz E, Munkholm P; EpiCom-group. East-West gradient in the incidence of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe: the ECCO-EpiCom inception cohort. Gut. 2014;63:588-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 311] [Cited by in RCA: 286] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12:1495-1499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3667] [Cited by in RCA: 6749] [Article Influence: 613.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, Ghali WA, Ferris M, Chernoff G, Benchimol EI, Panaccione R, Ghosh S, Barkema HW, Kaplan GG. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46-54.e42; quiz e30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3134] [Cited by in RCA: 3508] [Article Influence: 269.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 16. | van den Heuvel TRA, Jeuring SFG, Zeegers MP, van Dongen DHE, Wolters A, Masclee AAM, Hameeteman WH, Romberg-Camps MJL, Oostenbrug LE, Pierik MJ, Jonkers DM. A 20-Year Temporal Change Analysis in Incidence, Presenting Phenotype and Mortality, in the Dutch IBDSL Cohort-Can Diagnostic Factors Explain the Increase in IBD Incidence? J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:1169-1179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lee DW, Koo JS, Choe JW, Suh SJ, Kim SY, Hyun JJ, Jung SW, Jung YK, Yim HJ, Lee SW. Diagnostic delay in inflammatory bowel disease increases the risk of intestinal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23:6474-6481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Cantoro L, Di Sabatino A, Papi C, Margagnoni G, Ardizzone S, Giuffrida P, Giannarelli D, Massari A, Monterubbianesi R, Lenti MV, Corazza GR, Kohn A. The Time Course of Diagnostic Delay in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Over the Last Sixty Years: An Italian Multicentre Study. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11:975-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 8.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Riedl B, Kehrer S, Werner CU, Schneider A, Linde K. Do general practice patients with and without appointment differ? Cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Chmiel C, Vavricka SR, Hasler S, Rogler G, Zahnd N, Schiesser S, Tandjung R, Scherz N, Rosemann T, Senn O. Feasibility of an 8-item questionnaire for early diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease in primary care. J Eval Clin Pract. 2019;25:155-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Danese S, Fiorino G, Mary JY, Lakatos PL, D'Haens G, Moja L, D'Hoore A, Panes J, Reinisch W, Sandborn WJ, Travis SP, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Development of Red Flags Index for Early Referral of Adults with Symptoms and Signs Suggestive of Crohn's Disease: An IOIBD Initiative. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9:601-606. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Khaki-Khatibi F, Qujeq D, Kashifard M, Moein S, Maniati M, Vaghari-Tabari M. Calprotectin in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;510:556-565. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 16.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cantoro L, Monterubbianesi R, Falasco G, Camastra C, Pantanella P, Allocca M, Cosintino R, Faggiani R, Danese S, Fiorino G. The Earlier You Find, the Better You Treat: Red Flags for Early Diagnosis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023;13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |