Published online Jul 28, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i28.3418

Revised: June 5, 2024

Accepted: June 24, 2024

Published online: July 28, 2024

Processing time: 144 Days and 16 Hours

The concept of positive health (PH) supports an integrated approach for patients by taking into account six dimensions of health. This approach is especially relevant for patients with chronic disorders. Chronic gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreatico-biliary (GI-HPB) disorders are among the top-6 of the most prevalent chronically affected organ systems. The impact of chronic GI-HPB disorders on individuals may be disproportionally high because: (1) The affected organ system frequently contributes to a malnourished state; and (2) persons with chronic GI-HPB disorders are often younger than persons with chronic diseases in other organ systems.

To describe and quantify the dimensions of PH in patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders.

Prospective, observational questionnaire study performed between 2019 and 2021 in 235 patients with a chronic GI-HPB disorder attending the Outpatient Department of the Maastricht University Medical Center. Validated questionnaires and data from patient files were used to quantify the six dimensions of PH. Internal consistency was tested with McDonald’s Omega. Zero-order Pearson correlations and t-tests were used to assess associations and differences. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

The GI-HPB patients scored significantly worse in all dimensions of PH compared to control data or norm scores from the general population. Regarding quality of life, participation and daily functioning, GI-HPB patients scored in the same range as patients with chronic disorders in other organ systems, but depressive symptoms (in 35%) and malnutrition (in 45%) were more frequent in patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders. Intercorrelation scores between the six dimensions were only very weak to weak, forcing us to quantify each domain separately.

All six dimensions of PH are impaired in the GI-HPB patients. Malnutrition and depressive symptoms are more prevalent compared to patients with chronic disorders in other organ systems.

Core Tip: Patients with chronic gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreatico-biliary (GI-HPB) disorders experience complaints in every dimension of positive health (PH). We described and quantified these complaints and compared the outcomes with norm scores and other chronic diseases. We found that GI-HPB patients scored significantly worse in all dimensions of PH compared to control data or norm scores from the general population. Regarding quality of life, participation and daily functioning, GI-HPB patients scored in the same range as patients with chronic disorders in other organ systems, but depressive symptoms (in 35%) and malnutrition (in 45%) were more frequent in patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders.

- Citation: Lemlijn-Slenter AHWM, Wijnands KAP, van der Hamsvoort G, van Iperen LP, Wolter N, de Rijk AE, Masclee AAM. Positive health: An integrated quantitative approach in patients with chronic gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreatico-biliary disorders. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(28): 3418-3427

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i28/3418.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i28.3418

In the past decades, the prevalence of chronic disorders has steadily increased worldwide. In the Netherlands, over 55% of all inhabitants had been diagnosed with at least one chronic disorder in 2021. Increasing age is associated with an even higher prevalence of chronic disorders[1]. These developments have challenged healthcare providers to expand on the conventional definition of “health” beyond the focus on “absence of disease”. Chronic disorders significantly impact not only an individual’s physical well-being, but also mental well-being and social participation[2,3]. In 2011 Huber et al[4] proposed changing the focus of “health” to a more holistic vision, called “positive health” (PH). This approach emphasises a person’s ability to cope with life’s challenges and maintain self-management in relation to six dimensions: Bodily functions, mental well-being, quality of life (QOL), social participation, daily living and meaningfulness. By assessing a patient’s functioning in these six dimensions, a broader insight into their life and well-being is obtained. This integrated approach enables a more structured and potentially more relevant and personalised management of patients with chronic disorders.

There is an ongoing debate of how best to measure and quantify PH. Previous research has focused on the separate dimensions of PH, not on their coherence or through an integrated approach. To map PH during patient consultations, a dialogue tool was developed by the Institute for Positive Health[5]. Using 44 items, the six dimensions of PH are explored and the outcome visualised in a personal spider web. While this tool is helpful for individual clinical consultations, it does not systematically quantify all the PH dimensions to allow individual follow-up, group comparisons or scientific analyses. Recently, we proposed bridging this gap by measuring PH by merging validated, widely available ques-tionnaire instruments that, taken together, cover all the various dimensions of PH[6]. As a next step, PH should be quantified in patients with chronic disorders. Here we focus on a specific group of patients with chronic disorders.

Chronic gastrointestinal and hepato-pancreatico-biliary (GI-HPB) disorders are among the top 6 of most prevalent chronically affected organ systems[7]. The impact of chronic GI-HPB disorders on individuals may be disproportionally high because the affected organ system frequently contributes to a malnourished state and persons with chronic GI-HPB disorders are often younger than persons with chronic diseases in other organ systems.

The aim of the present study was to describe and quantify the six dimensions of PH in a group of patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders, compare their scores with norm scores (control groups, Dutch population data, disease controls) and test intercorrelations.

In this prospective, single-centre, observational, explorative questionnaire study, chronic GI-HPB patients attending the Gastroenterology-Hepatology Outpatient Clinic of the Maastricht University Medical Center (MUMC) were invited to participate. The MUMC is a university hospital for tertiary care and also provides secondary care for inhabitants of Maastricht and its surrounding area (250000 inhabitants). The Department of Gastroenterology-Hepatology has organised its care for patients with chronic disorders into three clinical pathways for: (1) Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD); (2) Chronic hepato-pancreatico-biliary (HPB) disorders; and (3) Neurogastroenterology and motility (NGM) disorders, also including functional gastrointestinal disorders, for which it is the national centre of expertise.

This survey is part of a more extensive MUMC study on PH in patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders. In the period from 2019-2021, a group of 1170 GI-HPB patients were contacted, of whom 555 participated (response rate 47.4%). As the questionnaire about meaningfulness was added later, only in a subset of 235 GI-HPB patients were all PH dimensions quantified using the combined, validated questionnaires. The local Medical Ethics Committee confirmed in a written statement that the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act (WMO) did not apply to this study (No. METC 2019-1324).

Patients aged 18 years and older who had been diagnosed with a chronic GI-HPB disorder (IBD, HPB or NGM) and were scheduled for an appointment at the Outpatient Clinic were invited by letter to participate in the study. The letter contained detailed information about the study. After signing the informed consent form, the patients received the questionnaires, filled them in and handed them back to the investigator after the clinical consultation. In addition to the questionnaires, clinical data were collected from their electronic patient files (medical diagnoses, duration of complaints, comorbidity, etc.).

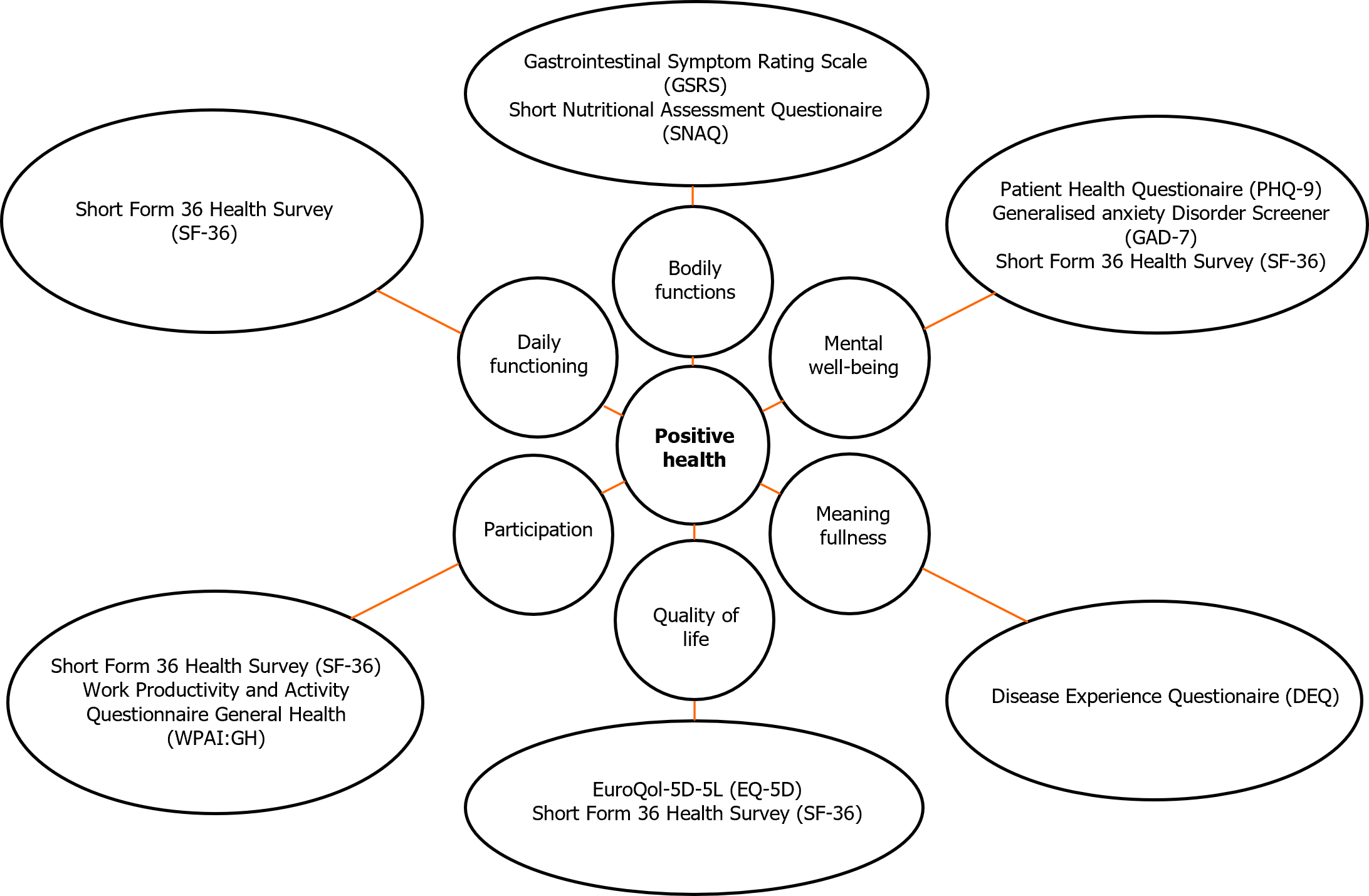

In Figure 1 the validated questionnaires and scales to quantify each of the six dimensions are presented. Each questionnaire is addressed in more detail below.

The bodily functions of GI-HPB patients were measured with the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)[8] that separates abdominal complaints into five symptom clusters on a seven-point Likert scale: Reflux, Abdominal pain, Indigestion, Diarrhoea and Constipation. McDonald’s Omega was adequate as a measure of internal consistency for the GSRS (0.857).

In addition, we used the Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnaire (SNAQ), an instrument developed to screen for malnutrition at hospitalisation. It provides insight into weight loss, loss of appetite and additional nutritional support[9]. A score ≥ 2 points to moderate malnutrition, a score ≥ 3 to severe malnutrition.

To evaluate mental well-being, depressive complaints (nine items) were measured with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)[10] and anxiety complaints (seven items) with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD-7)[11]. The PHQ-9 (range 0-27) and the GAD-7 (range 0-21) utilise answers on a four-point scale. Range of PHQ-9 scores: 5-9 mild; 10-14 moderate; 15-19 moderately severe; and 20-27 severe. Range of GAD-7 scores: 5-9 mild; 10-14 moderate; and 15-21 severe. A score of ≥ 10 represents the cut-off point to identify moderate to severe depression (PHQ-9) or moderate to severe anxiety disorder (GAD-7), at which point treatment is considered[12]. McDonald’s Omega was adequate for PHQ-9 (0.882) and GAD-7 (0.913).

The Short Form-36 (SF-36) is a questionnaire to quantify QOL and consists of nine subscales: e.g., physical functioning, social functioning, and physical or emotional role limitations. We distributed the subscales of the SF-36 over the various PH dimensions to find the best match with a specific dimension. Questions from the Mental Health subscale of the SF-36 were added to the Mental well-being dimension[13]. McDonald’s Omega was acceptable (0.864).

In 2020 the Disease Experience Questionnaire (DEQ) (Meaningfulness subscale, five items) was introduced and provides insight into the meaningfulness dimension[14]. The DEQ uses a five-point Likert scale. A higher score indicates that the chronic disorder is regarded as a more meaningful experience. Control data at the population level are not yet available. McDonald’s Omega was adequate (0.750).

The EuroQol (EQ)-5D-5 L measures QOL in five dimensions using a five-point Likert scale: Mobility, self-care, daily activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The patients’ health status was measured on a VAS scale (0-100). To obtain the EQ-5D-5L Crosswalk Value, a five-digit code consisting of the answers to the questions in the EQ-5D-5L was mapped to health status scores based on the study of M Versteegh et al[15]. Additionally, the SF-36 Vitality and General Health subscales were added to the PH QOL dimension.

The Social functioning, Emotional role limitations and Physical role limitations subscales of the SF-36 were used to score social and work participation. Participation was also measured with the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment-General Health (WPAI: GH)[16]. Additionally, for the subgroup of working age (18-66 years), a set of questions tailored to the Dutch work situation was used.

The SF-36 Physical functioning subscale was used to assess daily functioning and daily activities.

GSRS outcomes were compared to those of a group of healthy controls (n = 215) which we used previously as a control group for the Maastricht Irritable Bowel Syndrome Cohort[17]. Outcomes of the EQ-5D-5L and the SF-36 were compared to norm scores for the Dutch population[13,18,19]. SNAQ, PHQ-9 and GAD-7 were compared with previously defined cut-off values. For data on work participation, Dutch population control data were used[20].

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0. For the scales, internal consistency was tested with McDonald’s Omega. Zero-order Pearson correlations and t-tests were used to assess associations and differences. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant.

The group consisted of 235 chronic GI-HPB patients, mean age 50.2 years (SD 17.4), with more women than men (68.1%). The distribution among the subgroups was IBD 31.1% (n = 73), HPB 17.9% (n = 42) and NGM 51% (n = 120). Mean disease duration was 9.5 years (SD 10.3).

In 31.8% there were no comorbidities present, 19.7% had one comorbidity, 18.4% had two, and 30.1% had three or more. Almost everyone had a somatic comorbidity; 1.8% had only a mental comorbidity.

Bodily functions: GSRS scores for all five domains were significantly (P < 0.001) higher in GI-HPB patients compared to healthy controls (Table 1).

| Bodily functions | GI-HPB patients | Healthy controls |

| Patient characteristics | n = 235 | n = 215 |

| Age, years | 50.2 (17.4)b | 44.5 (10.0) |

| Sex, female | 68.1% | 61.4% |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.6 (6.3)a | 24.0 (3.8) |

| GSRS, mean (SD) | ||

| Reflux | 2.24 (1.68)b | 1.22 (0.53) |

| Abdominal pain | 3.15 (1.39)b | 1.65 (0.71) |

| Indigestion | 3.48 (1.47)b | 2.00 (0.89) |

| Diarrhoea | 3.02 (1.72)b | 1.41 (0.63) |

| Constipation | 2.82 (1.61)b | 1.61 (0.85) |

| SNAQ, n (%) | ||

| 0-1 | 125 (54.3) | |

| 2: Moderately malnourished | 55 (23.9) | |

| ≥ 3: Severely malnourished | 50 (21.7) |

Based on SNAQ data, moderate malnutrition (score 2) was present in 55 (23.9%) GI-HPB patients, while 50 (21.7%) had a score of ≥ 3 (severe malnutrition).

A mental disorder had previously been diagnosed in 26 of the 235 patients (11%). Depressive symptoms (PHQ score ≥ 10) were present in 34.9% and anxiety symptoms (GAD-7 score ≥ 10) in 21.6% of the GI-HPB patients (Table 2). Regarding the Mental health subscale of the SF-36, the mean score of the GI-HPB group was significantly (P < 0.001) reduced compared to the Dutch population norm score.

| Mental well-being | GI-HPB patients, n = 235 | Norm score of Dutch population |

| PHQ total | ||

| 0–9 | 149 (65.1) | |

| 10–max | 80 (34.9) | |

| GAD 7 total | ||

| 0–9 | 178 (78.4) | |

| 10–max | 49 (21.6) | |

| SF-36 | ||

| Mental Health, mean (SD) | 68.5 (21.2)b | 76.8 |

The GI-HPB group had a DEQ Meaningfulness subscale mean group score of 2.85 (SD 0.84; range 0-5). A higher score points to a greater impact of the chronic disorder on meaningfulness.

EQ-5D-5L scores were significantly (P < 0.001) reduced in the GI-HPB group compared to the Dutch population norm scores (Table 3). The Vitality and General perception of health subscales of the SF-36 were significantly (P < 0.001) lower in the GI-HPB group compared to the Dutch population.

The scores in the SF-36 subscales related to social participation were significantly (P < 0.001) lower compared to the Dutch population norm scores (Table 4).

| Participation | GI-HPB patients, n = 235 | Norm score of Dutch population |

| SF-36, mean (SD) | ||

| Social functioning | 60.1 (30.5)b | 86.9 |

| Physical role limitations | 39.9 (43.2)b | 79.4 |

| Emotional role limitations | 68.7 (42.6)b | 84.1 |

| Work, n (%) | ||

| Working age (18-66 years) | 191 (81.3) | |

| At work if working age (18-66 years) | 103 (54)b | 70% |

From the group of 235 GI-HPB patients, 81% was of working age (18-66 years). Of them, 54% was actively working, compared to 70% for the Dutch population (P < 0.001). Of those not working, the percentage of GI-HPB patients with a disability benefit was 36%.

The GI-HPB group scored significantly (P = 0.001) lower on the SF-36 Physical functioning subscale compared to the Dutch population.

Correlations between the dimensions were weak (0.2-0.4) or very weak (0.0-0.2). Correlations between the various QOL parameters (all subscales of SF-36, EQ-5D-5L and EQ-VAS) were moderate to strong (0.4-0.7), however. Patient characteristics (disease duration, number of comorbidities, etc.) showed very weak to weak correlations with the various PH dimensions. Higher GAD and PHQ scores indicating anxiety or depressive symptoms had a moderate negative correlation (-0.4 to -0.6) with all the quality-of-life parameters except for SF mental health, where the correlation was strong. Meaningfulness was the only parameter to show very weak correlations with all the other dimensions (0.0-0.2).

To arrive at an integrated assessment of patients with chronic disorders that includes their needs and wishes, it is important to know more about the patients than just their physical condition. We have described and quantified the health status of a group of patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders according to the six dimensions of PH by using an integrative and quantitative approach. To our knowledge, this study is the first to report on PH status in patients with chronic disorders using validated instruments for the various dimensions of PH. The results show that all dimensions of the health status of patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders are substantially impaired.

The group of 235 GI-HPB patients was divided into three subgroups. We focused on the complete GI-HPB group, not on comparisons between subgroups. Of the 235 GI-HPB patients, 68% had comorbidities. In the Dutch population, comorbidity is present in 57% of subjects[1]. In chronic disorders of other organ systems, similar percentages of comorbidity have been observed to our GI-HPB group[21-23]. Age, gender, BMI, disease duration and number of comorbidities revealed only weak correlations with the scores on the various PH dimensions.

In GI-HPB patients, GSRS were significantly higher in all symptom clusters compared to a historical control group. GSRS scores in our chronic GI-HPB patients were in the range of those previously reported in patients with IBD or irritable bowel syndrome. One limitation is that the GSRS only measures actual symptoms of the past seven days; it does not cover a longer timeframe.

The SNAQ score is used as a screening instrument for malnutrition in the (pre)hospital setting. In this setting, 27% of GI-HPB patients was previously found to be severely malnourished[24]. In the outpatient setting, severe malnutrition is much less frequent: Around 10% has been reported in non-specified, chronically diseased patients. Surprisingly, in our outpatient setting, 22% of the chronic GI-HPB patients was severely malnourished and 24% moderately malnourished. Thus, almost half of our chronic GI-HPB population is in need of nutritional guidance/support. A substantial percentage of these patients would not have been identified without the use of the SNAQ.

Symptoms of depression and anxiety were more frequent in chronic GI-HPB patients compared to the Dutch population: 34.9% and 21.6% compared to 8.5% and 15%, respectively[25]. For patients with chronic diseases of other organ systems, prevalence data on depressive symptoms of 20%-30% and on anxiety symptoms of 16%-32% have been observed[26-28]. Depressive symptoms appear to be more prevalent in our chronic GI-HPB population compared to other chronically diseased populations. Because mental disorders can influence GI-HPB symptoms, it is important to identify them. In a large proportion of GI-HPB patients, mental symptoms were not recognized, although they are present to an extent that treatment should be considered. We recommend more systematic screening for depression and anxiety disorder in patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders and, when indicated, initiating targeted treatment.

The DEQ is designed to measure three disease experiences, including meaningfulness. A meaningful life is associated with positive functioning: Life satisfaction, enjoyment of work, happiness, general positive affect, hope and a higher level of well-being. Our GI-HPB group scored a mean of 2.85 on this scale. For comparison, a mean score of 3.16 has been reported in the recent literature for patients with sarcoidosis, a chronic pulmonary disorder[14].

We anticipated that lower scores of physical, mental and social well-being would be associated with higher scores of meaningfulness, pointing to a greater impact of the disease on well-being and functioning. Meaningfulness showed only a very weak, insignificant correlation with all other dimensions of PH. For an integrated, multidimensional approach to chronically diseased patients, it is essential to be informed about a patient’s opinion and rating of their life’s meaningfulness. In this respect, the DEQ is a first step that deserves further evaluation.

The GI-HPB patients scored significantly lower on all QOL parameters compared to the Dutch norm population. QOL scores in the GI-HPB group are comparable to those found in various chronic disorders of other organ systems[29-31].

Scores for the three SF-36 subscales related to social participation were all significantly lower compared to the Dutch population as a whole but were in the range of patients with chronic diseases in other organ systems.

Work participation was significantly lower in the GI-HPB group compared to the Dutch norm population (54% vs 71%) but in the range of 40%-60% observed in patients with chronic diseases in other organ systems[32-34]. Of the GI-HPB patients who were not working, only 36% received a disability benefit. Compared to other high-income countries, the percentage of disabled people living in poverty is higher in the Netherlands due to a high threshold for the disability benefit. Early recognition of problems in work participation is essential in order to refer patients for advice and support, and thus prevent prolonged sick leave, resulting in a non-working status with disability pension or unemployment.

For daily functioning (SF-36 Physical functioning subscale), the GI-HPB group scored significantly worse compared to the Dutch norm population, while the score is in the range of patients with chronic disorders in other organ systems[30,35,36].

One strength of our study is that it bridges the gap between conceptualisation and implementation of PH by using validated questionnaires to quantify each dimension in an integrated fashion. In this way, a broad and personalised picture of a patient’s well-being was obtained. It allowed us to generate data for individual follow-up, for comparison between groups and for scientific purposes. Although confirmation is needed from other GI-HPB centres and from patients with chronic disorders of other organ systems, our data on PH in chronic GI-HPB patients provide a unique and valuable insight. Our group is fairly representative of the chronic GI-HPB patient population as a whole, with a somewhat higher percentage of patients with chronic NGM or functional disorders because we function as a national NGM centre of expertise.

A limitation for generalisation to other patient groups is that we used an organ-specific instrument, the GSRS, for physical symptom assessment. Assessment of PH in chronic disorders of other organ systems will require other organ-specific or more general health-oriented instruments for physical symptom assessment that cover longer periods of time than the past week or month.

In general, correlations between the various dimensions were relatively weak. Therefore, an inventory of PH should contain instruments to score all the separate dimensions. For an individual patient, attention should be paid to all dimensions to obtain an overall picture.

In the guidance and management of patients with chronic disorders, use of the PH concept may be helpful. Improving the physical condition of a patient is essential but is not the ultimate goal. It serves as a first step towards better mental and social well-being, daily functioning, work participation and a meaningful life.

In conclusion, describing and quantifying PH revealed that the health status of patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders is substantially impaired in all dimensions. Regarding QOL, social and work participation, daily functioning and meaningfulness, the scores are in the range of patients with chronic disorders in other organ systems, while depressive symptoms and malnutrition were more prevalent in patients with chronic GI-HPB disorders. Intercorrelation scores between the six dimensions were very weak to weak, compelling us to quantify each domain separately. We have shown that quantifying PH in patients with chronic disorders can be successfully performed in standard care using validated instruments.

| 1. | RIVM. Chronische aandoeningen en multimorbiditeit, leeftijd en geslacht Netherlands 2022. Nov 29, 2022 [cited 21 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.vzinfo.nl/chronische-aandoeningen-en-multimorbiditeit/leeftijd-en-geslacht. |

| 2. | De Boer AG, Bennebroek Evertsz' F, Stokkers PC, Bockting CL, Sanderman R, Hommes DW, Sprangers MA, Frings-Dresen MH. Employment status, difficulties at work and quality of life in inflammatory bowel disease patients. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:1130-1136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schreiber S, Panés J, Louis E, Holley D, Buch M, Paridaens K. National differences in ulcerative colitis experience and management among patients from five European countries and Canada: an online survey. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:497-509. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Huber M, Knottnerus JA, Green L, van der Horst H, Jadad AR, Kromhout D, Leonard B, Lorig K, Loureiro MI, van der Meer JW, Schnabel P, Smith R, van Weel C, Smid H. How should we define health? BMJ. 2011;343:d4163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1302] [Cited by in RCA: 1090] [Article Influence: 77.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Institute for Positive Health. Procesnotitie Doorontwikkeling Mijn Positieve Gezondheid. Dec 16, 2021. [cited 21 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.iph.nl/assets/uploads/2021/12/20211119-procesnotitie-doorontwikkeling-spinnenweb-als-gespreksinstrument.pdf. |

| 6. | Lemlijn-Slenter AHWM, Wijnands KAP, de Rijk A, Masclee AAM. Mapping positive health in patients with gastrointestinal disorders. BMJ Open. 2021;11:e052688. |

| 7. | Linden M, Linden U, Goretzko D, Gensichen J. Prevalence and pattern of acute and chronic multimorbidity across all body systems and age groups in primary health care. Sci Rep. 2022;12:272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Svedlund J, Sjödin I, Dotevall G. GSRS--a clinical rating scale for gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome and peptic ulcer disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1988;33:129-134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 884] [Cited by in RCA: 1037] [Article Influence: 28.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kruizenga HM, Seidell JC, de Vet HC, Wierdsma NJ, van Bokhorst-de van der Schueren MA. Development and validation of a hospital screening tool for malnutrition: the short nutritional assessment questionnaire (SNAQ). Clin Nutr. 2005;24:75-82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 345] [Cited by in RCA: 402] [Article Influence: 20.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 28910] [Article Influence: 1204.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 18844] [Article Influence: 991.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Löwe B. The Patient Health Questionnaire Somatic, Anxiety, and Depressive Symptom Scales: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:345-359. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3056] [Cited by in RCA: 2740] [Article Influence: 182.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zee van der KI. Het meten van de algemene gezondheidstoestand met de RAND-36, een handleiding. Groningen: Noordelijk Centrum voor Gezondheidsvraagstukken, 1993: 28. |

| 14. | Galardi M, Houkes I, de Rijk A. Validation of the disease experience questionnaire for working age adults with chronic conditions. European Journal of Public Health. 2020;30:Supplement_5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | M Versteegh M, M Vermeulen K, M A A Evers S, de Wit GA, Prenger R, A Stolk E. Dutch Tariff for the Five-Level Version of EQ-5D. Value Health. 2016;19:343-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 767] [Article Influence: 85.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Reilly MC, Bracco A, Ricci JF, Santoro J, Stevens T. The validity and accuracy of the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment questionnaire--irritable bowel syndrome version (WPAI:IBS). Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20:459-467. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 136] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mujagic Z, Ludidi S, Keszthelyi D, Hesselink MA, Kruimel JW, Lenaerts K, Hanssen NM, Conchillo JM, Jonkers DM, Masclee AA. Small intestinal permeability is increased in diarrhoea predominant IBS, while alterations in gastroduodenal permeability in all IBS subtypes are largely attributable to confounders. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:288-297. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Aaronson NK, Muller M, Cohen PD, Essink-Bot ML, Fekkes M, Sanderman R, Sprangers MA, te Velde A, Verrips E. Translation, validation, and norming of the Dutch language version of the SF-36 Health Survey in community and chronic disease populations. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1055-1068. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1547] [Cited by in RCA: 1693] [Article Influence: 62.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Janssen B, Szende A. Population Norms for the EQ-5D. 2013 Sep 26. In: Self-Reported Population Health: An International Perspective based on EQ-5D [Internet]. Dordrecht (NL): Springer; 2014–. [PubMed] |

| 20. | Statistics Netherlands. Werkenden. 2023. [cited 21 June 2024]. Available from: https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-arbeidsmarkt/werkenden. |

| 21. | Sharma A, Zhao X, Hammill BG, Hernandez AF, Fonarow GC, Felker GM, Yancy CW, Heidenreich PA, Ezekowitz JA, DeVore AD. Trends in Noncardiovascular Comorbidities Among Patients Hospitalized for Heart Failure: Insights From the Get With The Guidelines-Heart Failure Registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11:e004646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lee WC, Lee YT, Li LC, Ng HY, Kuo WH, Lin PT, Liao YC, Chiou TT, Lee CT. The Number of Comorbidities Predicts Renal Outcomes in Patients with Stage 3⁻5 Chronic Kidney Disease. J Clin Med. 2018;7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kreuter M, Ehlers-Tenenbaum S, Palmowski K, Bruhwyler J, Oltmanns U, Muley T, Heussel CP, Warth A, Kolb M, Herth FJ. Impact of Comorbidities on Mortality in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 216] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kruizenga H, van Keeken S, Weijs P, Bastiaanse L, Beijer S, Huisman-de Waal G, Jager-Wittenaar H, Jonkers-Schuitema C, Klos M, Remijnse-Meester W, Witteman B, Thijs A. Undernutrition screening survey in 564,063 patients: patients with a positive undernutrition screening score stay in hospital 1.4 d longer. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103:1026-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 94] [Cited by in RCA: 104] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | ten Have M, Tuithof M, van Dorsselaer S, Schouten F, de Graaf R. NEMESIS Kerncijfers psychische aandoeningen Vóórkomen van psychische aandoeningen Utrecht2022. Nov 30, 2022. [cited 19 September 2023]. Available from: https://cijfers.trimbos.nl/nemesis/kerncijfers-psychische-aandoeningen/voorkomen-psychische-aandoeningen/#12maands. |

| 26. | Costa FMD, Martins SPV, Moreira ECTD, Cardoso JCMS, Fernandes LPNS. Anxiety in heart failure patients and its association with socio-demographic and clinical characteristics: a cross-sectional study. Porto Biomed J. 2022;7:e177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pérez-García LF, Silveira LH, Moreno-Ramírez M, Loaiza-Félix J, Rivera V, Amezcua-Guerra LM. Frequency of depression and anxiety symptoms in Mexican patients with rheumatic diseases determined by self-administered questionnaires adapted to the Spanish language. Rev Invest Clin. 2019;71:91-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Takita Y, Takeda Y, Fujisawa D, Kataoka M, Kawakami T, Doorenbos AZ. Depression, anxiety and psychological distress in patients with pulmonary hypertension: a mixed-methods study. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2021;8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Choi HS, Yang DW, Rhee CK, Yoon HK, Lee JH, Lim SY, Kim YI, Yoo KH, Hwang YI, Lee SH, Park YB. The health-related quality-of-life of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients and disease-related indirect burdens. Korean J Intern Med. 2020;35:1136-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Wolfe F, Michaud K, Li T, Katz RS. EQ-5D and SF-36 quality of life measures in systemic lupus erythematosus: comparisons with rheumatoid arthritis, noninflammatory rheumatic disorders, and fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:296-304. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Yarlioglu AM, Oguz EG, Gundogmus AG, Atilgan KG, Sahin H, Ayli MD. The relationship between depression, anxiety, quality of life levels, and the chronic kidney disease stage in the autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Int Urol Nephrol. 2023;55:983-992. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | de Jong RW, Boezeman EJ, Chesnaye NC, Bemelman FJ, Massy ZA, Jager KJ, Stel VS, de Boer AGEM. Work status and work ability of patients receiving kidney replacement therapy: results from a European survey. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:2022-2033. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Leso V, Romano R, Santocono C, Caruso M, Iacotucci P, Carnovale V, Iavicoli I. The impact of cystic fibrosis on the working life of patients: A systematic review. J Cyst Fibros. 2022;21:361-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Sokka T, Kautiainen H, Pincus T, Verstappen SM, Aggarwal A, Alten R, Andersone D, Badsha H, Baecklund E, Belmonte M, Craig-Müller J, da Mota LM, Dimic A, Fathi NA, Ferraccioli G, Fukuda W, Géher P, Gogus F, Hajjaj-Hassouni N, Hamoud H, Haugeberg G, Henrohn D, Horslev-Petersen K, Ionescu R, Karateew D, Kuuse R, Laurindo IM, Lazovskis J, Luukkainen R, Mofti A, Murphy E, Nakajima A, Oyoo O, Pandya SC, Pohl C, Predeteanu D, Rexhepi M, Rexhepi S, Sharma B, Shono E, Sibilia J, Sierakowski S, Skopouli FN, Stropuviene S, Toloza S, Valter I, Woolf A, Yamanaka H; QUEST-RA. Work disability remains a major problem in rheumatoid arthritis in the 2000s: data from 32 countries in the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Cruz MC, Andrade C, Urrutia M, Draibe S, Nogueira-Martins LA, Sesso Rde C. Quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66:991-995. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 136] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Huber A, Oldridge N, Höfer S. International SF-36 reference values in patients with ischemic heart disease. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2787-2798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |