Published online Mar 28, 2024. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v30.i12.1676

Peer-review started: November 20, 2023

First decision: December 7, 2023

Revised: December 20, 2023

Accepted: March 18, 2024

Article in press: March 18, 2024

Published online: March 28, 2024

Processing time: 129 Days and 4.5 Hours

The top goal of modern medicine is treating disease without destroying organ structures and making patients as healthy as they were before their sickness. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has dominated the surgical realm because of its lesser invasiveness. However, changes in anatomical structures of the body and reconstruction of internal organs or different organs are common after traditional surgery or MIS, decreasing the quality of life of patients post-operation. Thus, I propose a new treatment mode, super MIS (SMIS), which is defined as “curing a disease or lesion which used to be treated by MIS while preserving the integrity of the organs”. In this study, I describe the origin, definition, operative channels, advantages, and future perspectives of SMIS.

Core Tip: The top goal of modern medicine is treating diseases without destroying organ structures and making patients as healthy as they were before their sickness. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has predominated among surgeries, but it fails to avoid some downsides of traditional surgery, as it still changes anatomical structures and leads to reconstruction of internal organs or different organs. In this study, I describe a new treatment mode, super MIS, which is defined as “curing the disease while preserving the integrity of the organs”.

- Citation: Linghu EQ. New direction for surgery: Super minimally invasive surgery. World J Gastroenterol 2024; 30(12): 1676-1679

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v30/i12/1676.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v30.i12.1676

With the development of new equipment and the growing experiences of experts, surgery has become less invasive. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) has dominated the surgical realm for years, but, no matter how developed MIS is, the treatment mode is still ultimately the same. Classic surgical operations are based on organ resection. This breaks the anatomical structures of the body to some degree. Reconstruction of internal organs or different organs is common after traditional surgery and MIS. The reconstruction changes the programmed body functions, which might lead to dysfunction of organ(s) or discomfort in the patients. Although the disease has been cured, the quality of life (QoL) of patients has decreased. Such treatment methods may be required for advanced cancers, but they can be too radical for early cancers or benign lesions.

The human body continues to evolve to adapt to its environment. The current physiological and anatomical structure should be most suitable for the modern environment. Each organ of the human body plays its own unique roles and they interact with each other. The operating mechanism of the body is complex, and little is known about it. Scientists have failed to explain the mystery of the human body comprehensively, and even the functions of individual organs have not been fully explained. For example, the appendix, which used to be regarded as useless, is now known to regulate immune functions. Treatments such as biomaterial implantation and organ transplantation aim to restore the original structure of the human body as much as possible and simulate its natural condition. The top goal of modern medicine (or treatment modes) is treating the disease without destroying the organ structure and making patients as healthy as they were before their sickness.

Therefore, a new treatment mode, named “super MIS (SMIS)”, was first proposed by Linghu[1] in 2016. This new mode is defined as “curing the diseases that used to be treated by MIS while preserving the integrity of the organs”. Organ resection is inevitable during MIS and traditional surgery. Organ resection and reconstruction are not involved in SMIS, making the procedures less invasive and promoting a better QoL[2,3]. SMIS includes not only endoscopic surgery, but also some surgical operations. Therapies for diseases are advancing over time and there are always more expected operative methods than existing ones.

SMIS is mainly operated through four operative channels. The first channel is the natural lumen, through which the surgery can be called natural orifice translumenal endoscopic surgery (NOTES). The following treatment methods are examples of SMIS through the natural orifice: Endoscopic submucosal dissection (ESD), endoscopic mucosal resection, endoscopic submucosal excavation, endoscopic full-thickness resection[4], and so on. The second one is the submucosal tunnel. A tunnel is made between mucosal and muscularis propria layers. This kind of SMIS is also called the digestive endoscopic tunnel technique (DETT) for gastrointestinal lesions[5]. The following treatment methods are classical examples of SMIS through the submucosal channel: Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection (ESTD), submucosal tunnel endoscopic resection, and peroral endoscopic myotomy. The third tunnel is the transmural channel, exemplified by video-assisted thoracoscopic enucleation which only resects lesions through the skin or cholangioscopy-assisted extraction of choledocholithiasis without endoscopic sphincterotomy[6,7]. The last one is multi-cavity channels. This type of SMIS includes the cooperation of different treatment methods, such as laparoscopy- or thoracoscopy-assisted endoscopic surgery.

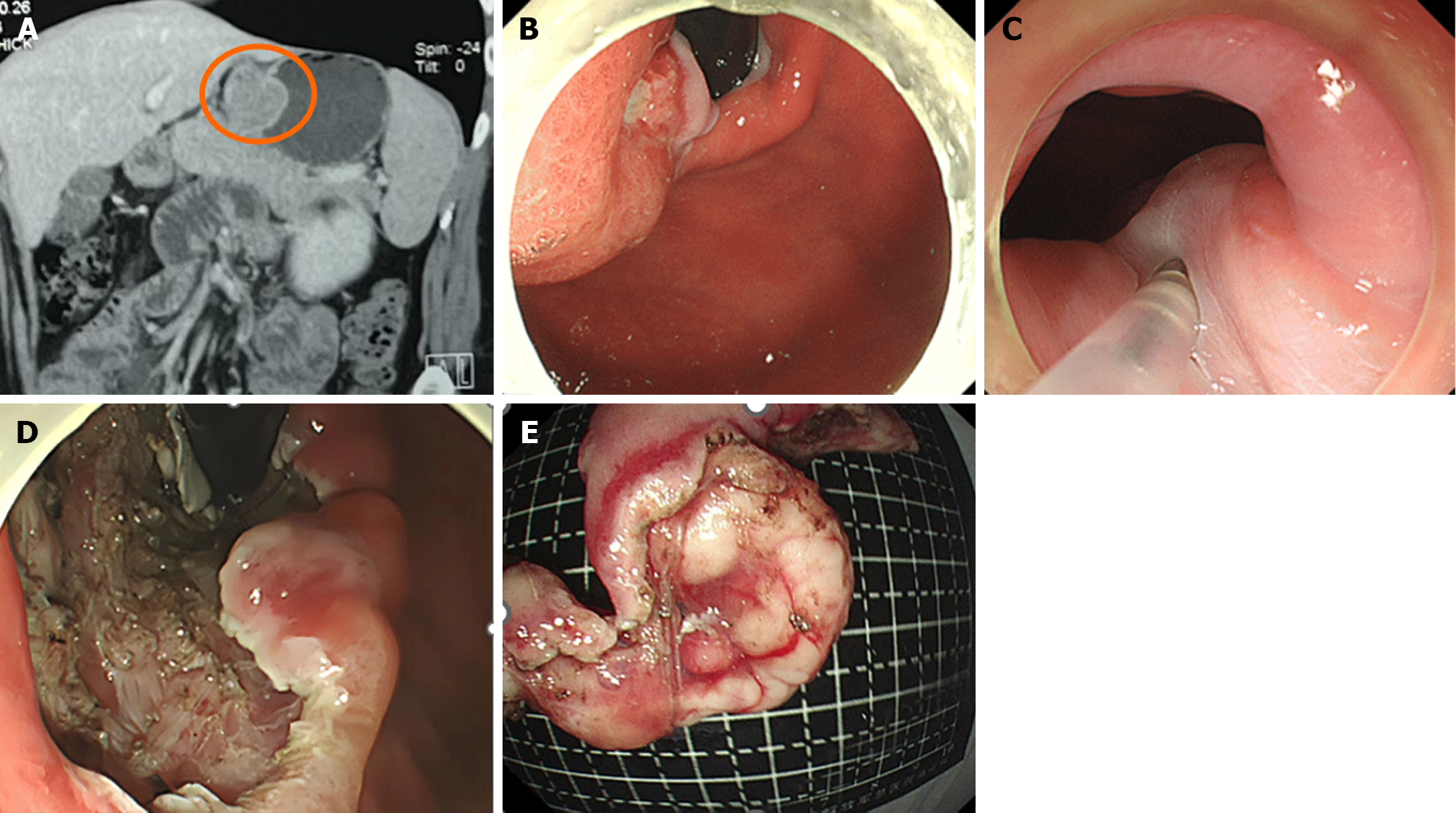

Taking digestive diseases as an example, SMIS can be mainly divided into two types, resection and drainage. Resection can be applied to most of the benign lesions and early malignant lesions which need surgical removal while drainage is mainly applicable to benign lesions. Benign lesions, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors, lipomas, leiomyomas, and polyps, can be resected by SMIS while malignant lesions, such as early gastrointestinal tumors and neuroendocrine tumors, could also be resected by SMIS without breaking the integrity of their located organs. For example, SMIS has been used to resect a large tumor at the cardia without breaking the integrity of the organ (Figure 1). Drainage is mainly used to treat pancreatic pseudocysts, pancreatic walled-off necrosis, gallbladder stones, biliary tract stones, suppurative cholangitis, and suppurative appendicitis. The applications of SMIS are restricted by surgical instruments and the experience of the operators. Not all benign lesions can be treated by SMIS. Lesions with a large size or rich blood supply are not indicated for SMIS. However, I believe that SMIS will have a broader scope for benign diseases in the near future. With more and more malignant lesions being detected in their early stage, more malignant lesions will also be treatable by SMIS.

The different treatment modes between SMIS and MIS/traditional surgery can lead to distinct prognoses. Taking early cancer located on the gastric cardia or near the gastric cardia as an example, ESD or ESTD was used to resect the tumor, leaving the cardial structures free from damage (Video 1). Both MIS and traditional surgery would resect not only the tumor but also the cardia, and even all or some of the stomach and some of the esophagus. The esophagus and stomach were connected to reconstruct an artificial gastroesophageal conjunction (Video 2). The gastroesophageal anastomosis failed to play the role of low esophageal sphincter, which has anti-reflux effects. Losing the cardia made patients suffer from abnormal gastrointestinal dynamics and reflux. These patients must sit up in bed to avoid the symptoms of heartburn. As compared to patients after MIS and traditional surgery, those after SMIS lived as healthy as they did without cardial cancer.

I expect SMIS to be widely used in the near future. I hope that it can point to the new direction of surgery and be applicable to more than digestive diseases. I believe that all diseases could eventually be treated without changing any anatomic structure. SMIS could be regarded as a goal for the treatment of diseases that will be widely used for diseases of many systems.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Chinese Society of Digestive Endoscopy, President; Endoscopy Branch of Chinese Medical Association, Vice President; Digestive Endoscopy Branch, Beijing Medical Association, President; Digestive Endoscopy Branch, Beijing Physicians Association, President; Chinese Journal of Gastroenteroscopy Electronics, Editor-in-Chief; Chinese Journal of Digestive Endoscopy, Vice President.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Zimmitti G, Italy S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Chen YX

| 1. | Linghu E. A new stage of surgical treatment: super minimally invasive surgery. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:1-3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Feng J, Chai N, Linghu E, Feng X, Li L, Du C, Zhang W, Wu Q. Outcomes of super minimally invasive surgery vs. esophagectomy for superficial esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a single-center study based on propensity score matching. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:2491-2493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Meng M, Chai N, Liu S, Feng X, Linghu E. Health-related quality of life after super minimally invasive surgery and proximal gastrectomy for early-stage adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction: a propensity score-matched study. Chin Med J (Engl). 2022;135:3022-3023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Li X, Zhang W, Gao F, Dong H, Wang J, Chai N, Linghu E. A modified endoscopic full-thickness resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors: A new closure technique based on the instruction of super minimally invasive surgery. Endoscopy. 2023;55:E561-E562. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chai NL, Li HK, Linghu EQ, Li ZS, Zhang ST, Bao Y, Chen WG, Chiu PW, Dang T, Gong W, Han ST, Hao JY, He SX, Hu B, Huang XJ, Huang YH, Jin ZD, Khashab MA, Lau J, Li P, Li R, Liu DL, Liu HF, Liu J, Liu XG, Liu ZG, Ma YC, Peng GY, Rong L, Sha WH, Sharma P, Sheng JQ, Shi SS, Seo DW, Sun SY, Wang GQ, Wang W, Wu Q, Xu H, Xu MD, Yang AM, Yao F, Yu HG, Zhou PH, Zhang B, Zhang XF, Zhai YQ. Consensus on the digestive endoscopic tunnel technique. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:744-776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zhang W, Chai N, Li H, Feng X, Zhai Y, Liu S, Wang J, Linghu E. Cholangioscopy-assisted basket extraction of choledocholithiasis through papillary support without endoscopic sphincterotomy: a pilot exploration for super minimally invasive surgery. VideoGIE. 2023;8:232-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zhang W, Chai N, Zhai Y, Li H, Liu S, Gao F, Linghu E. Cholangioscopy-assisted extraction of choledocholithiasis and partial sediment-like gallstones through papillary support: A pilot exploration for super minimally invasive surgery. Endoscopy. 2023;55:E274-E275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |