Published online Feb 28, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i8.1330

Peer-review started: September 30, 2022

First decision: December 1, 2022

Revised: December 9, 2022

Accepted: February 14, 2023

Article in press: February 14, 2023

Published online: February 28, 2023

Processing time: 150 Days and 23.9 Hours

This was an observational, descriptive, and retrospective study from 2011 to 2020 from the Department of Informatics of the Brazilian Healthcare System database.

To describe the intestinal complications (IC) of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) who started conventional therapies in Brazil´s public Healthcare system.

Patients ≥ 18 years of age who had at least one claim related to UC 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) code and at least 2 claims for conventional therapies were included. IC was defined as at least one claim of: UC-related hospitalization, pro

In total, 41229 UC patients were included (median age, 48 years; 65% women) and the median (interquartile range) follow-up period was 3.3 (1.8-5.3) years. Conventional therapy used during follow-up period included: mesalazine (87%), sulfasalazine (15%), azathioprine (16%) or methotrexate (1%) with a median duration of 1.9 (0.8-4.0) years. Overall IR of IC was 3.2 cases per 100 PY. Among the IC claims, 54% were related to associated diseases, 20% to procedures and 26% to hospitalizations. The overall annual incidence of IC was 2.9%, 2.6% and 2.5% in the first, second and third year after the first claim for therapy (index date), respectively. Over the first 3 years, the annual IR of UC-related hospitalizations ranged from 0.8% to 1.1%; associated diseases from 0.9% to 1.2% - in which anus or rectum disease, and malignant neoplasia of colon were the most frequently reported; and procedure events from 0.6% to 0.7%, being intestinal resection and polyp removal the most frequent ones.

Study shows that UC patients under conventional therapy seem to present progression of disease developing some IC, which may have a negative impact on patients and the burden on the health system.

Core Tip: This population-based study investigated intestinal complications (ICs) in patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) undergoing therapy available in the public healthcare system (Sistema Único de Saúde) of Brazil over the last decade. Our results showed that some patients with UC undergoing conventional therapy, seem to present an active and progressive disease and develop relevant ICs, which demand important resources of the healthcare system and have a negative impact on their lives.

- Citation: Martins AL, Galhardi Gasparini R, Sassaki LY, Saad-Hossne R, Ritter AMV, Barreto TB, Marcolino T, Yang Santos C. Intestinal complications in Brazilian patients with ulcerative colitis treated with conventional therapy between 2011 and 2020. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(8): 1330-1343

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i8/1330.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i8.1330

Ulcerative Colitis (UC) is an idiopathic inflammatory disease of the mucosa and colon that commonly involve colonic regions both proximal to and distal from the site of the primary lesion[1]. The typical presentation includes symptoms such as bloody diarrhea, rectal urgency, and abdominal pain[2]. UC is a component of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which are chronic, immune-mediated inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. The etiopathogenesis is multifactorial involving different environmental, genetic, immune-mediated and intestinal microbial factors[3].

Although epidemiological studies are still scarce in developing countries, the incidence and prevalence of UC is increasing worldwide, along with IBD[4]. A systematic review showed that the incidence and prevalence of UC in Latin America varied between regions and studies, ranging from 0.04 to 8.00/100000 and 0.23 to 76.1/100000, respectively, and generally increased over the period from 1986 to 2015[5].

Many patients have long periods of complete remission, but the cumulative probability of remaining relapse-free for two years is only 20%, decreasing to less than 5% in 10 years[6]. Chronic inflammation of the colorectal mucosa, as is typically found in UC, is a proven risk factor for neoplasm of colon. The development of neoplasm of colon in patients with UC is related to several factors: Duration, extent, activity, severity and family history of the disease. The progression from UC inflammation to neoplasm and/or surgery is a multi-step process in which the accumulation of symptoms and sequential mucosal changes gradually transition to a low-grade change to neoplasm[7]. Indications for emergency surgery include refractory toxic megacolon, perforation, and ongoing severe colorectal bleeding[8].

UC is a progressive disease that can lead to other serious complications and/or even life-threatening complications. One of the most common UC disease progressions are: anorectal dysfunction (50%)[9], proximal extension (25%) with the greatest proximal extension occurring during the first 10 years[10,11], pseudopolyposis (16%)[12] and other such as impaired permeability in remission or with mucosal healing, stenosis and dysmotility[10]. Thus, complications related to UC represent a substantial burden in terms of costs and patient quality of life, with hospital admissions, operations and treatments being the most relevant burdens[13].

The treatment of UC currently aims to monitor indicators of disease activity and to adjust therapy, aiming to achieve clinical remission and prevent long-term complications, such as dysplasia, colorectal cancer, hospitalizations and colectomy[14]. In 2021, the STRIDE-II study confirmed STRIDE-I's long-term goals of clinical remission, histological remission, and endoscopic mucosal healing[15] and added absence of disability, restoration of quality of life, and normal growth in children. Symptomatic relief and normalization of serum and fecal markers were determined as short-term targets[16].

Treatment will vary depending on the severity and location of the UC. For proctitis, topical therapy with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) compounds is used. For more severe UC, oral and local 5-ASA compounds and corticosteroids are indicated to induce remission. For patients who do not respond to these treatments, intravenous steroids are used. When refractory to this, calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus), tumor necrosis factor-α antibodies or immunomodulators are then used[17].

For patients with moderate to severe UC, drugs such as thiopurines and biologics are indicated to control symptoms and heal the intestinal mucosa. Anti-tumor necrotizing factor (TNF) drugs include infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab. Of the anti-integrin drug, vedolizumab can be mentioned. And the anti-p40 antibody targeting interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-23, we can mention ustekinumab and small molecules (Janus Kinase inhibitor - tofacitinib)[18]. Biologics were not available in the public healthcare system during the study period in Brazil. Studies have observed an association between the administration of biologics therapies such as anti-TNF-α within the first 2 years of diagnosis and several beneficial effects, including reduction risk of intestinal surgery[4,5,19].

There are few population-based studies documenting the evaluation and progression of the conventional therapy-using patient of the UC disease phenotype. Thus, this study aims to describe the intestinal complications (IC) of patients with UC who started treatment with conventional therapies between January 2011 and January 2020 in the Brazilian healthcare system.

For this study, data were collected from two Department of Informatics of the Brazilian Healthcare System (DATASUS) databases: Hospitalizations Information System (SIH), which contains hospitalization data[20] and the Outpatient Information System (SIA), which contains data on outpatient care[21,22].

The causes of hospital admissions are coded according to the 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10). The SIH was used to identify the number and causes of hospital admissions related to UC and/or its IC.

The SIA is the system that allows local managers to process outpatient care information recorded in outpatient care capture applications by public and private providers contracted/agreed by the public healthcare system (SUS). Most SIA subsets have an ID code that enables linking the outpatient procedures to a single patient. Because SIH does not have patient ID information, a probabilistic record linkage (RLK) was performed allowing longitudinal assessment in SIH and SIA at a patient-level. The RLK relied on multiple steps with different combination of patient information from both databases, such as date of birth, gender and ZIP code, making it possible to identify patients in both systems.

Data is presented as procedure codes from billing records and includes demographic information, all procedures such as inpatient and outpatient performance, number of procedures, and other additional information.

The present study is a descriptive, observational, retrospective study of secondary data collected between 2011 and 2020, which used the DATASUS to characterize IC in patients with UC.

We considered UC patients those who had at least one report of UC ICD-10 code (K51). The date of the first request for UC conventional therapy was considered as the index date. Conventional therapies used for UC treatment were based on procedures codes available at DATASUS, according to the following list: Sulfasalazine; Mesalazine; Azathioprine; Methotrexate; Cyclosporine. UC patients must had at least two claims of conventional therapy to be included in the study. They were followed from the index date until the last information available in the DATASUS regardless of being under conventional treatment or not. One or more conventional therapies could had been used at the same time and/or in sequence by the patient, due to that line of treatment and comparisons between different conventional therapies were not assessed in this study.

We also assessed sociodemographic, such as age, sex and location of residency of the patient. Measurements of IC information in UC patients were extracted, including procedures performed, hospitalization causes, and diseases developing in the study sample. Each pre-defined claim of IC reported after conventional therapy initiation was considered as a progression of the UC disease.

Pre-defined claims of ICs were validated based on four independent medical expert opinions and literature about the natural history and evaluation of UC[23]. Patients who progressed from UC to malignant neoplasm of colon, stenosis, hemorrhage, ulcer or other specified diseases or symptoms of anus and rectum, functional diarrhea, megacolon, volvulus, intussusception or erythema nodosum or any intestinal surgery or hospitalization related to the disease was considered to have experienced an IC.

The following claims were considered as proxy of ICs: any claim for anus, rectum or intestinal surgeries for procedures, any claim of hospitalization reporting UC ICD-10 codes for hospitalization and/or any claim of ICD-10 code pre-defined for associated diseases [Table 1, list of diseases (ICD-10 code) considered as IC in consequence of underlying UC disease].

| ICs | Description of ICs | Patients (n = 1273) | % | Procedure-related complications | Patients (n = 1125) | % | |

| Associated disease (ICD-10–related complications) | 0407020403 | Abdominal rectosigmoidectomy | 167 | 15 | |||

| K62 | Other diseases of the anus and rectum | 1070 | 78 | 0407020390 | Body removed – rectum or colon polyps | 145 | 13 |

| C18 | Malignant neoplasms of the colon | 255 | 19 | 0407020063 | Partial colectomy | 135 | 12 |

| K59 | Other functional intestinal disorders | 66 | 5 | 0407020209 | Enteroctomy and/or resection | 128 | 11 |

| L52 | Erythema nodosum | 27 | 2 | 0407020101 | Colostomy | 105 | 9 |

| K56 | Paralytic ileus and intestinal obstruction without hernia | 3 | 0.2 | 0407020128 | Dilatation of the anus and/or rectum | 91 | 8 |

| K51 | Ulcerative colitis | 2 | 0.1 | 0407020098 | Abdominal colporrhaphy | 51 | 5 |

| C63 | Malignant neoplasms of other and unspecified male genital organs | 1 | 0.1 | 0407020241 | Enterostomy closure | 50 | 4 |

| 0407020187 | Enteroanastomy | 41 | 4 |

Overall ICs could reflect one or more type of ICs, so, in an attempt to represent them, IC analyses sets were stratified into 3 groups based on the type of IC: (1) Procedures: If claim of procedure code for anus, rectum or intestinal surgeries; (2) Hospitalizations: If claim of hospitalization for UC (reported UC ICD-10 in inpatient setting); and (3) Associated disease: If claim of ICD-10 code for diseases pre-defined as UC complications, such as C18 (malignant neoplasm of colon), K62.4 (stenosis of anus and rectum), K62.5 (hemorrhage of anus and rectum), K62.6 (ulcer of anus and rectum), K62.8 (other specified diseases of anus and rectum), K62.9 (disease of anus and rectum, unspecified), K59.1 (functional diarrhea), K59.3 (megacolon, not elsewhere classified), K56.2 (volvulus), K56.1 (intussusception), or L52 (erythema nodosum). Thus, to be considered a case of IC, patients must have at least one medical complaint in one or more of the sub-groups of ICs previously described.

In the data analysis, the annual IC in UC patients per each calendar year, and the incidence per 100 people of ICs were evaluated throughout the study. Patients whose UC progressed after the conventional treatment initiation timeframe were recorded as an IC annual rate and expressed year (from 1 to 5 years) according to the number of claims (total and mean) and the number of patients (total and percentage according to the number of patients in follow-up at the database at the respective year Also, the mean ICs per each patient were assessed and expressed by calendar year. The incidence of IC was converted into units per patient/year by dividing them for all patients by the person-years of follow-up, because each individual attends a different time in the database. Thus, the incidence rate was calculated as the number of intestinal events divided by the total person-time at risk. Considering that one patient could present one or more types of IC, we also expressed the total of ICs found in the study.

The most frequent ICs related to procedures in UC population were assessed according to the number of patients with at least one procedure for anus, rectum or intestinal surgeries during the study period. The most frequent ICs related to associated disease in UC population was assessed according to the number of patients with at least one ICD-10 code of pre-defined associated-disease.

Patients were included in the study if they were aged ≥ 18 years old, if they had evidence of UC [at least one ICD-10 claim of UC (K51.0, K51.2, K51.3, K51.4, K51.5, K51.8 or K51.9)] and if they had at least one claim of conventional treatment of UC. The UC conventional therapies (synthetic) considered in the present study were sulfasalazine, mesalazine, azathioprine, methotrexate and cyclosporine.

To capture the initial stage of treatment, patients must have had no claims for conventional and/or anti-TNF therapy prior to the index date. Thus, the period from January 2010 to December 2011 was considered only for the evaluation of the medical history of patients who had the index date in 2011.

Considering that fissure and fistula of anal and rectal regions (K60) and/or abscess of anal and rectal regions (K61) are considered an uncommon IC in UC patients, but common in other IBD, we excluded patients with at least one ICD-10 claim of these diseases after index date (first claim of UC conventional treatment code). Additionally, patients with less than 6 months of follow-up in the database and patients who were not exclusive to the SUS were excluded. Non-SUS exclusive was defined as patients who used the SUS only to obtain high-cost medications and who carried out the rest of the treatment and medical care through their private health plan[24]. Thus, they are patients who had claims related to medications only.

Although only descriptive analyses were performed, a statistical review of the study was performed by a statistician. Results were described as measures of central tendency (means, medians) and spread (variance, range) for continuous variables (e.g., age); absolute number and percentage for categorical variables (e.g., sex) and Kaplan Meier Curve for time to event data. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated according to the variable, normal distribution for continuous variable, normal approximation to binominal distribution for proportion and Poisson distribution for incidence rate, as applicable.

The age variable was calculated based on the difference between the date of birth and the first conventional therapy claim reported (index date). The age was described as continuous variable, including the mean, standard deviation, median and quartiles. For the sex and race variables, they were described as categorical variables, with absolute frequencies and percentage.

Time of follow-up was calculated based on the difference between date of first claim of conventional therapy (index date) and the last date of patient information available at database. Conventional treatment profile of UC patients was evaluated and expressed by the percentage of patient who had at least one claim of UC therapy. Patients could change, add or stopped some of the conventional therapies (sulfasalazine, mesalazine, azathioprine, methotrexate and cyclosporine) during the treatment approach, therefore, the patient may have used one or more conventional therapies during the study period. Conventional treatment initiation was expressed as the number of patients (absolute and percentage) per calendar year (2011-2020) according to the first claim of the conventional therapy in the database. Timing using conventional therapy was calculated based on the first and the last claim of the therapy presented by the patient regardless of gaps. Switch conventional therapy was considered when it had at least one claim of different conventional therapy than the previous one. The time between one conventional therapy to another conventional therapy was described as continuous variable, including the mean, standard deviation, median and quartiles of the mean.

The main outcomes were regarding ICs in patients who initiated on conventional treatment between 2011 and 2020 in the SUS. Since each individual attended different amount of time in the database, some ICs parameters were analyzed as the frequency per person-years of follow-up. For incidence rate, confidence interval was estimated by Poisson rate confidence interval. The number of claims and the number of patients with at least one claim were expressed to address the total number of claim [patient could present more than one IC (claim) for the respective group of IC] and the total number of patients with at least one IC (claim).

Missing values were reported as missing information and imputation methods were not used. When needed, patient was censored for IC analyses. For Kaplan-Meier curve the last information available of the patient or the end of the study period was considered as censored for patients who did not present IC. IC was not assessed according to the conventional treatment received and neither if patient discontinued or not discontinued the conventional therapy treatment. Data was analyzed using Python version 3.6.9.

In the present study, a total of 41229 patients with UC meeting the inclusion criteria were exposed to conventional medications between 2011 to 2020 in DATASUS. Most patients were female (65%) and were reported as white (56%). The mean ± SD age was 48 ± 15.42 years old, with a mean ± SD follow-up of 3.65 ± 2.27 years. Most patients (56%) were in the Southeast region of Brazil, followed by South (21%), and Northeast (14%) (Table 2).

| Variable | n | % |

| Patients | 41229 | 100 |

| Age1, yr | ||

| mean ± SD | 48.86 ± 15.42 | |

| Median (IQI) | 48.09 (60.15-36.94) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 14417 | 35 |

| Female | 26812 | 65 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 23290 | 56 |

| Black and other | 11987 | 33 |

| Missing | 4643 | 11 |

| CVT initiation | ||

| 2011 | 4300 | 10 |

| 2012 | 4054 | 10 |

| 2013 | 4259 | 10 |

| 2014 | 4877 | 12 |

| 2015 | 4846 | 12 |

| 2016 | 5039 | 12 |

| 2017 | 5565 | 13 |

| 2018 | 5040 | 12 |

| 2019 | 3249 | 8 |

| Follow-up time2, yr | ||

| mean ± SD | 3.65 (2.27) | |

| Median (IQI) | 3.25 (1.75-5.26) | |

| Region of residence | ||

| Southeast | 22942 | 56 |

| South | 8831 | 21 |

| Midwest | 2638 | 6 |

| Northeast | 5833 | 14 |

| North | 985 | 2 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 |

| Patients under CVT | ||

| Mesalazine | 35923 | 87 |

| Sulfasalazine | 6148 | 15 |

| Azathioprine | 6413 | 16 |

| Ciclosporine | 116 | 0 |

| Methotrexate | 290 | 1 |

| Time using CVT3, yr | ||

| mean ± SD | 2.64 (2.29) | |

| Median (IQI) | 1.92 (0.75-4.00) | |

| Patients switched treatment after first IC4 | 2564 | 6 |

| Time to switch treatment after IC, yr | ||

| mean ± SD | 0.36 (0.76) | |

| Median (IQI) | 0.08 (0.08-0.25) | |

| Min | 0.08 | |

All patients with UC had received conventional therapy and the mean ± SD time using each was 2.64 ± 2.29 years. Regarding the conventional treatment profile for patients with UC, mesalazine had the highest proportion (87%). Azathioprine was the second (16%) and sulfasalazine the third (15%) most frequent drugs among patients with UC. Methotrexate was reported only by 1% of the patients and cyclosporine by less than 1% (Table 2).

Table 3 shows the incidence rate of bowel complications in patients with UC exposed to conventional treatment. The overall IR was 2.55 (2.46-2.63) per 100 patients. The IR of associated diseases (ICD-10-related), procedures-related and UC hospitalizations were 0.93 (0.89-0.98), 0.76 (0.71-0.80) and 0.97 (0.92-1.02), respectively. Considering that one patient could present more than one IC, a total of 6711 bowel complications claims were reported over the study period in these patients (Table 3).

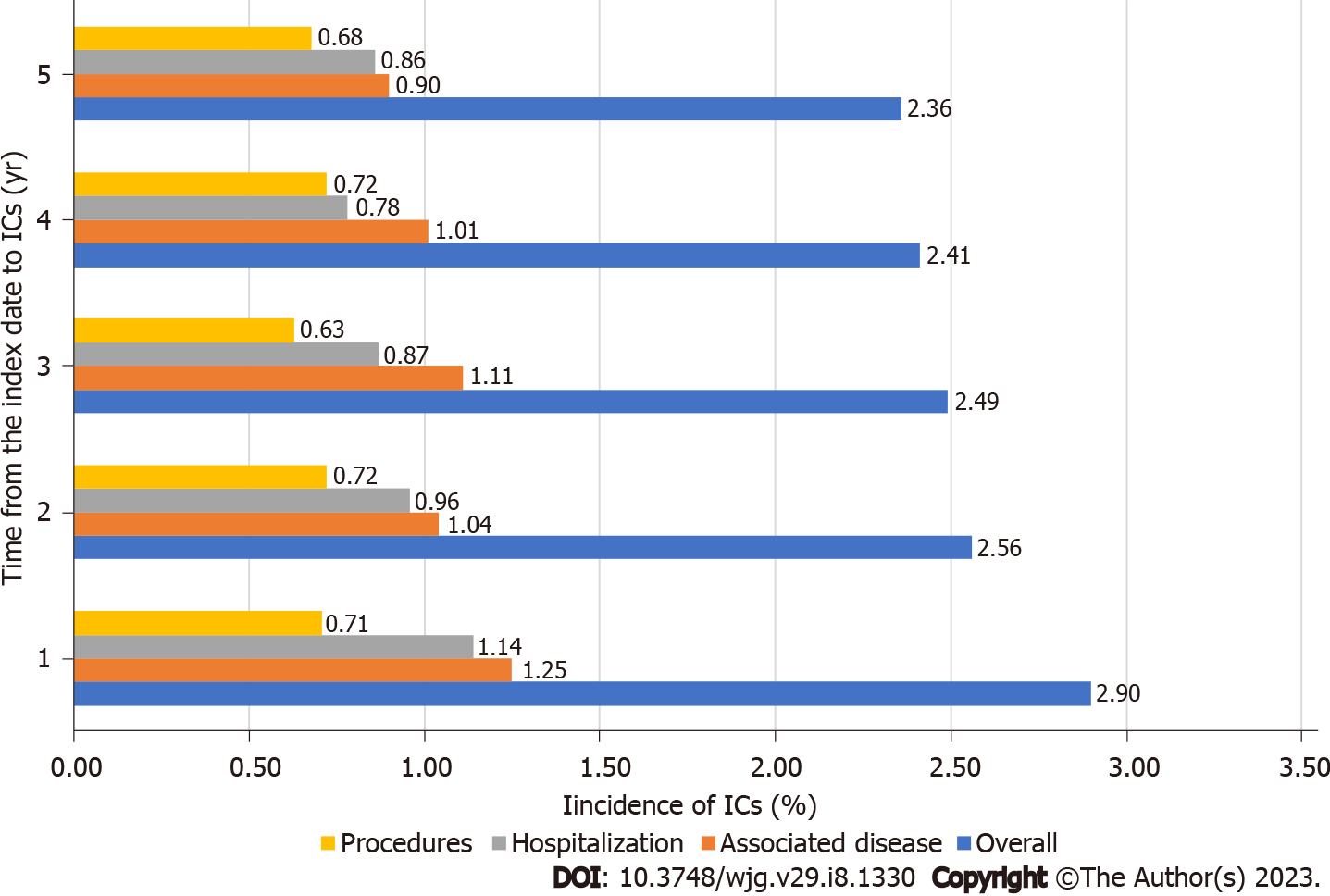

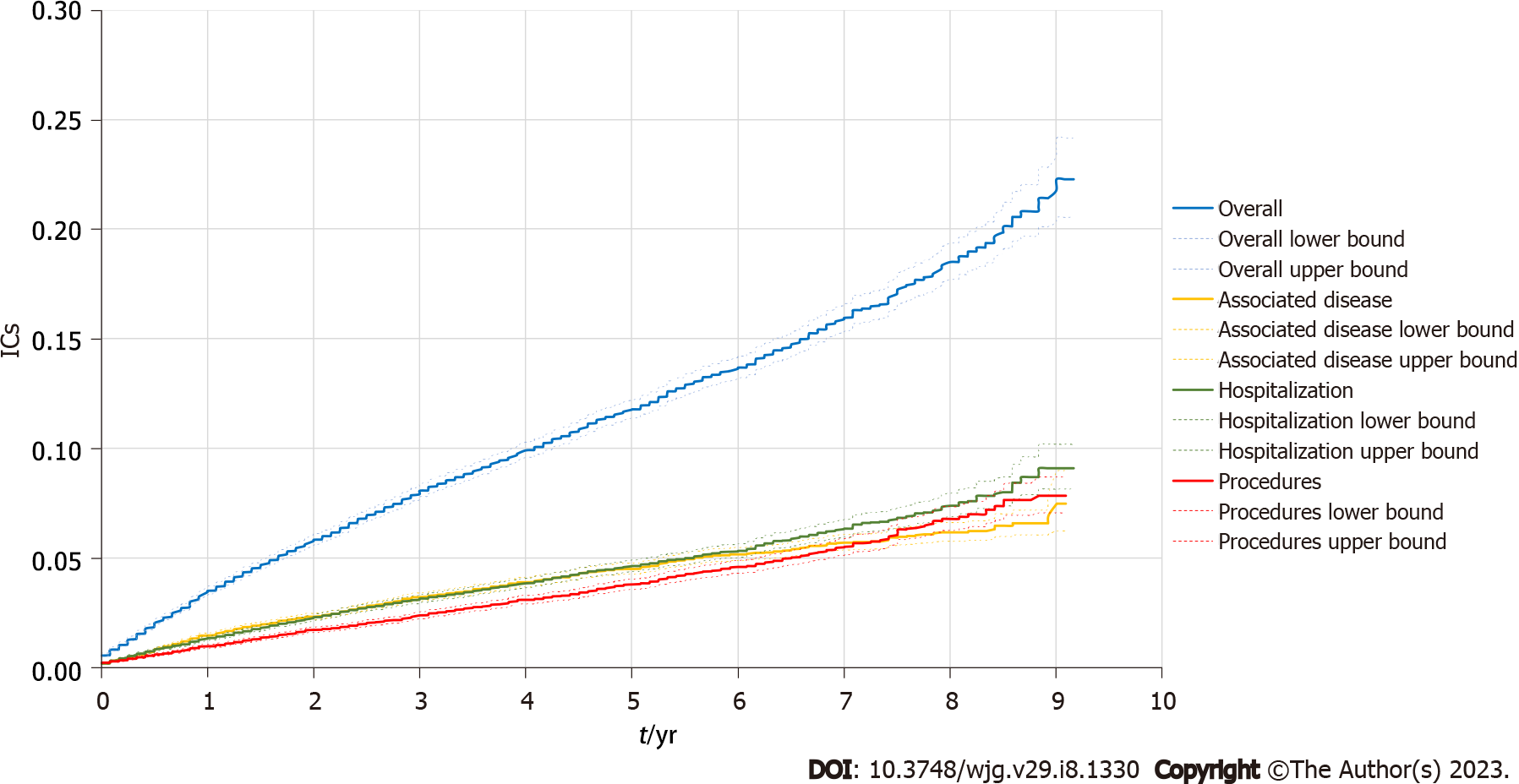

Regarding the annual IC (overall and segregated types) in patients with UC, during the study period (≤ 1 year and 5 years), the overall complications rates were 2.90% at one year and 2.36% at 5 years. Segregated by type, complications related to the associated diseases (ICD-10) were1.18% and 0.88%; the procedure-related complications were 0.71% and 0.68%; and the complications related to hospitalizations due to colitis was 1.10% and 0.84%, respectively (Table 4). The mean number of events per patient was also similar over the years for both the overall and the segregated IC types in patients with UC (Table 4). A description of the time to event for overall and segregated IC type in the population with UC is shown in Figure 1. In the Kaplan-Meier analysis, the probability to present any type of ICs (overall) was approximately 20% by the end of the study period. The segregated IC types had a comparable probability to present an event (less than 10% for procedures, hospitalization and associated disease) by the end of the study period (Figure 2).

| Overall | Associated disease (ICD-10–related) | Procedure-related | UC-related hospitalization | |||||||||||||

| Patients (n) | % | Claims (n) | mean ± SD | Patients (n) | % | Claims (n) | mean ± SD | Patients (n) | % | Claims (n) | mean ± SD | Patients (n) | % | Claims (n) | mean ± SD | |

| ≤ 1 yr (n = 41229) | 1197 | 2.90 | 1582 | 1.32 ± 1.3 | 487 | 1.18 | 763 | 1.57 ± 1.92 | 293 | 0.71 | 312 | 1.06 ± 0.29 | 456 | 1.10 | 520 | 1.14 ± 0.44 |

| 2 yr (n = 36389) | 931 | 2.56 | 1250 | 1.34 ± 1.35 | 355 | 0.98 | 601 | 1.69 ± 2.08 | 262 | 0.72 | 284 | 1.08 ± 0.36 | 343 | 0.94 | 376 | 1.1 ± 0.32 |

| 3 yr (n = 28795) | 716 | 2.49 | 953 | 1.33 ± 1.39 | 305 | 1.06 | 493 | 1.62 ± 2.05 | 182 | 0.63 | 201 | 1.1 ± 0.34 | 242 | 0.84 | 263 | 1.09 ± 0.34 |

| 4 yr (n = 22012) | 531 | 2.41 | 668 | 1.26 ± 1.16 | 219 | 0.99 | 323 | 1.47 ± 1.72 | 158 | 0.72 | 170 | 1.08 ± 0.37 | 163 | 0.74 | 177 | 1.09 ± 0.32 |

| 5 yr (n = 16510) | 389 | 2.36 | 457 | 1.17 ± 0.88 | 146 | 0.88 | 190 | 1.3 ± 1.36 | 113 | 0.68 | 115 | 1.02 ± 0.13 | 139 | 0.84 | 155 | 1.12 ± 0.36 |

From the 1273 patients with IC due to disease associated to UC found in the study, the categories Other diseases of the anus and rectum (78%), Colon malignant neoplasm (19%), Other functional intestinal disorders (5%) were the most common ones (Table 1).

Additionally, for the 1125 patients with IC due to procedures performed in consequence of the UC progression, it was found that abdominal rectosigmoidectomy (15%), body removed-rectal or colon polyps (13%) and partial colectomy (12%) were the most common ones (Table 1).

The length of hospitalization stay was 6.62 ± 6.62 d and the number of procedures performed during a hospitalization was 0.32 ± 0.28. The most common hospitalization procedure was the treatment of non-infectious enteritis and colitis (77%), followed by diagnosis and/or emergency care at a medical clinic (7%) and treatment of other intestinal diseases (4%) (Table 5).

| Length of hospitalization and procedures | mean ± SD | Median (IQI) | Procedures (inpatient most common procedures1) | Patients (n = 1426) | % | |

| ICs | Description of ICs | |||||

| Hospitalization (inpatient) | 303070099 | Treatment of enteritis and colitis not infectious | 1103 | 77 | ||

| Length of hospital stay, d (PPPY) | 6.62 ± 6.62 | 4.60 (2.63-8.11) | 301060088 | Diagnose and/or emergence care in medical clinic | 102 | 7 |

| Number of procedures performed (PPPY) | 0.32 ± 0.28 | 0.23 (0.15-0.38) | 303070110 | Treatment of other intestinal diseases | 56 | 4 |

| 301060070 | Diagnosis and/or emergence care in surgery clinic | 47 | 3 | |||

| 415010012 | Treatment with multiple surgeries | 44 | 3 | |||

| 415020034 | Other procedures with following surgeries | 30 | 2 | |||

| 407020071 | Total colectomy | 29 | 2 | |||

| 303070102 | Treatment of digestive tract disease | 23 | 2 | |||

| 407020330 | Total proctocolectomy | 12 | 1 | |||

| 303010061 | Exploratory laparotomy | 9 | 1 | |||

The present study described some specific categories of ICs in patients with UC treated with conventional therapies available in the public health system in Brazil between January 2011 and January 2020. Women, who were reported as white and from the Southeast region were the patients with the highest proportions in this study. The mean time of use of conventional therapy was 2.64 years and mesalazine was the most conventional therapy used. The mean age of UC patients treated with conventional medication in SUS was 48.86 years. This finding is similar to another database study, which reported that the highest proportion of patients with UC was in the 45-54 age group[25].

UC is considered a global burden due to its high prevalence and incidence in developed countries. Lima Martins et al[26], in 2014, carried out a study in Brazil, presenting a UC incidence of 5.3/100000 inhabitants/year. In São Paulo, Brazil the incidence of UC was 8/100000 inhabitants per year in 2015[27]. A study carried out in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern in Brazil found an incidence of UC of approximately 0.6/100000 inhabitants per year in 2012[28].

Demographic characteristics of patients with UC in DATASUS showed that the large proportion of patients were from the Southeast region and the minority from the North region of Brazil. Although these regions represent one of the highest and lowest densities in the country, respectively, the number of UC cases in each region may also be due to social differences and inequalities in access to health services found in the country, in line with previous Brazilian perspectives findings reported in the literature[29].

Several studies have shown that uncontrolled UC is associated with structural damage and impaired gastrointestinal functioning[30]. This population-based study in Brazil depicted the year-by-year proportion of patients with IC under conventional therapy in SUS. During the first year and the last 5 years of follow-up, about 2.90% and 2.36%, respectively, of the patients had one or more IC in consequence of the UC progression. The rate of IC also appeared not to be high, similarly found in another international study. Thus, the proportion of patients with some complication seems to be constant over time even under treatment. It is known that continuing conventional therapy in some cases may delay more effective therapy and place patients at risk for worsening disease and complications[31].

Although the rates of ICs in the present study might be underestimated due to intrinsic limitation of the method applied, the impact of the progression of UC disease with consequent complication for the health system and patient might be significant, especially due to the severity and type of the complication generated for the patient. We found that almost 4% of the UC patients performed a surgery and/or procedure of anus or rectum during the study period. Surgical complications represent a substantial burden in terms of cost and quality of life, with reoperations, medical fees and additional hospital admissions being the main cost factors[13].

The associated diseases observed in the present study were mainly represented by other diseases of rectum and anus (78%) followed by the malignant neoplasm of colon (19%). Literature shows that UC patients with severe and persistent inflammation have an increased risk of developing neoplasm of colon[32]. In the United States, the prevalence of neoplasm of colon in a patient with UC was about 3.7%[33], in Spain was 11.7%[34]. It is well known that cancer is more likely to develop in patients with extensive colitis lasting 8-10 years or more[35]. In our investigation, the average follow-up period was only 3.65 years. Thus, it is possible that our results would be improved by a longer follow-up period.

Although no direct statistical comparison was performed, the incidence rates of ICs found in the present study indicate that ICs related to diseases associated to UC (ICD-10 code) were the highest, followed by those related to the procedure and finally hospitalization for UC. Only hospitalization related to ICD-10 of UC was considered in this study, which may imply underestimated rates. That is, if the patient was hospitalized due to the progression of the disease, other ICDs-10 codes were probably used and, therefore, was not counted in this study. Even though, we might assume that conventional therapy was not able to control the inflammatory process for all patients leading them to seek urgent and emergency services, or even been hospitalized and/or require surgeries procedures.

Conventional medical treatment for UC may have limited efficacy or serious adverse reactions[36]. Currently, 20% to 40% of patients with UC do not respond to conventional therapies and may receive secondary drug treatment or even colectomy. Anti-TNF agents were the first biologics to be used in the treatment of IBD, including infliximab and adalimumab. Other biologics therapies that target specific immune pathways has been implemented in several countries, including in Brazil, as potential therapeutics for UC[37,38]. In this line, Vedolizumab was recently approved by ANVISA for the treatment of adult patients with moderate to severe UC[39] who are not responding to one or more conventional treatments, such as steroids, immunosuppressive agents or TNF blockers[36]. However, during the study period, there was no biological therapy available in the SUS.

The treatments available in the SUS until 2020 involved the use of aminosalicylates (sulfasalazine and mesalazine), corticosteroids (hydrocortisone and prednisone), immunosuppressants (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine and (intravenous cyclosporine), and antibiotics[40]. Biological therapy was included in the national protocol of UC treatment in early 2020[40,41]. Before that period, patients who needed biological therapy had to find other strategies besides the SUS to get biologic therapies for UC treatment, such as out of pocket, private healthcare and/or even judicial action.

The main limitations of this study are related to the retrospective design of the study and the potential information biases and attrition of this study. With regard to information bias, the lack of information can lead to underestimation of results. Longitudinal and time-dependent analyzes of data correction are more accurate, however, DATASUS data end up being limited by this. Another limitation refers to the availability of medicines by the SUS, which are not always available and/or are available at different times during the period of this study, such as corticosteroids. Use of conventional therapy was an assumption based on the first claim of each drug at the database, so the patients could have not been under treatment during all the study period. However, as a real word study, this scenario reflects the daily life of UC patients. The severity of the disease was not considered in the analyses due to methodological limitations.

Additionally, for data analysis, the inpatient database (SIH) does not have patient identification and the use of probabilistic RLK, event rates may be underestimated, as they are mainly captured in outpatient databases (SIA). As it is a descriptive observational study, it is prone to confounding factors that are difficult to control or assess. In an attempt to reduce these biases, broad terms of procedures and ICD-10s related to possible complications were used. Although the ICD-10 codes used, procedures and hospitalization were predefined as ICs, other diseases and/or procedures related to UC could be codes could have been studied as ICs proxy, however, we were not able to predict all ICD-10.

UC have impact both for the population and public system (SUS) due to its clinical management and development of comorbidities and associated diseases. The results of this study highlight some issues regarding the progression of UC in patients who were treated with conventional therapies in the Brazilian public system showing that a percentage of UC patients have presented IC during the history of the disease. Most of the IC represent an important demand to the health system, with a need for health support and hospitalization. Current UC therapies, as well as innovative therapies that effectively alleviate UC symptoms, along with the implementation of an adequate program to access and manage therapy for patients with UC, may improve the control or progression of UC and consequently decrease the negative the impact of the disease.

This was an observational, descriptive, and retrospective study from 2011 to 2020 from the Department of Informatics of the Brazilian Healthcare System database.

To understand the real world situation of patients with ulcerative colitis (UC) in the public healthcare system.

Describe the intestinal complications (IC) of patients with UC who started conventional therapies.

Patients ≥ 18 years of age who had at least one claim related to UC International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) code and at least 2 claims for conventional therapies were included. IC was defined as at least one claim of: UC-related hospitalization, procedures code for rectum or intestinal surgeries, and/or associated disease defined by ICD-10 codes.

In total, 41229 UC patients were included. Overall IR of IC was 3.2 cases per 100 PY. Among the IC claims, 54% were related to associated diseases, 20% to procedures and 26% to hospitalizations. The overall annual incidence of IC was 2.9%, 2.6% and 2.5% in the first, second and third year after the first claim for therapy (index date), respectively. Over the first 3 years, the annual IR of UC-related hospitalizations ranged from 0.8% to 1.1%; associated diseases from 0.9% to 1.2%.

Study shows that UC patients under conventional therapy seem to present progression of disease developing some IC, which may have a negative impact on patients and the burden on the health system.

Biologics were implemented in the public healthcare system after the study period, it would be interesting to verify the IC impact of this implementation in patients with UC.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Gu GL, China; Wen H, China; Yang BL, China S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

| 1. | Tripathi K, Feuerstein JD. New developments in ulcerative colitis: latest evidence on management, treatment, and maintenance. Drugs Context. 2019;8:212572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ghosh S, Shand A, Ferguson A. Ulcerative colitis. BMJ. 2000;320:1119-1123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shivashankar R, Tremaine WJ, Harmsen WS, Loftus EV Jr. Incidence and Prevalence of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis in Olmsted County, Minnesota From 1970 Through 2010. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:857-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 253] [Cited by in RCA: 345] [Article Influence: 43.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kotze PG, Steinwurz F, Francisconi C, Zaltman C, Pinheiro M, Salese L, Ponce de Leon D. Review of the epidemiology and burden of ulcerative colitis in Latin America. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2020;13:1756284820931739. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hendriksen C, Kreiner S, Binder V. Long term prognosis in ulcerative colitis--based on results from a regional patient group from the county of Copenhagen. Gut. 1985;26:158-163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Tonelli F, Di Martino C, Amorosi A, Mini E, Nesi G. Surgery for ulcerative colitis complicated with colorectal cancer: when ileal pouch-anal anastomosis is the right choice. Updates Surg. 2022;74:637-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Meier J, Sturm A. Current treatment of ulcerative colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:3204-3212. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Brochard C, Siproudhis L, Ropert A, Mallak A, Bretagne JF, Bouguen G. Anorectal dysfunction in patients with ulcerative colitis: impaired adaptation or enhanced perception? Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;27:1032-1037. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Torres J, Billioud V, Sachar DB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF. Ulcerative colitis as a progressive disease: the forgotten evidence. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1356-1363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 157] [Cited by in RCA: 206] [Article Influence: 15.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Roda G, Narula N, Pinotti R, Skamnelos A, Katsanos KH, Ungaro R, Burisch J, Torres J, Colombel JF. Systematic review with meta-analysis: proximal disease extension in limited ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1481-1492. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Massinha P, Portela F, Campos S, Duque G, Ferreira M, Mendes S, Ferreira AM, Sofia C, Tomé L. Ulcerative Colitis: Are We Neglecting Its Progressive Character. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2018;25:74-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lindsay JO, Bergman A, Patel AS, Alesso SM, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Systematic review: the financial burden of surgical complications in patients with ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1066-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Ungaro R, Colombel JF, Lissoos T, Peyrin-Biroulet L. A Treat-to-Target Update in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:874-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 28.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, D'Haens G, Dotan I, Dubinsky M, Feagan B, Fiorino G, Gearry R, Krishnareddy S, Lakatos PL, Loftus EV Jr, Marteau P, Munkholm P, Murdoch TB, Ordás I, Panaccione R, Riddell RH, Ruel J, Rubin DT, Samaan M, Siegel CA, Silverberg MS, Stoker J, Schreiber S, Travis S, Van Assche G, Danese S, Panes J, Bouguen G, O'Donnell S, Pariente B, Winer S, Hanauer S, Colombel JF. Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324-1338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1487] [Cited by in RCA: 1395] [Article Influence: 139.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (115)] |

| 16. | Turner D, Ricciuto A, Lewis A, D'Amico F, Dhaliwal J, Griffiths AM, Bettenworth D, Sandborn WJ, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Schölmerich J, Bemelman W, Danese S, Mary JY, Rubin D, Colombel JF, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Dotan I, Abreu MT, Dignass A; International Organization for the Study of IBD. STRIDE-II: An Update on the Selecting Therapeutic Targets in Inflammatory Bowel Disease (STRIDE) Initiative of the International Organization for the Study of IBD (IOIBD): Determining Therapeutic Goals for Treat-to-Target strategies in IBD. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:1570-1583. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 473] [Cited by in RCA: 1576] [Article Influence: 394.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Uchino M, Ikeuchi H, Bando T, Chohno T, Sasaki H, Horio Y, Kuwahara R, Minagawa T, Goto Y, Ichiki K, Nakajima K, Takahashi Y, Ueda T, Takesue Y. Associations between multiple immunosuppressive treatments before surgery and surgical morbidity in patients with ulcerative colitis during the era of biologics. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Hupé M, Rivière P, Nancey S, Roblin X, Altwegg R, Filippi J, Fumery M, Bouguen G, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Bourreille A, Caillo L, Simon M, Goutorbe F, Laharie D. Comparative efficacy and safety of vedolizumab and infliximab in ulcerative colitis after failure of a first subcutaneous anti-TNF agent: a multicentre cohort study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:852-860. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Filippi J, Allen PB, Hébuterne X, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Does anti-TNF therapy reduce the requirement for surgery in ulcerative colitis? Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:1440-1447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bittencourt SA, Camacho LA, Leal Mdo C. O Sistema de Informação Hospitalar e sua aplicação na saúde coletiva [Hospital Information Systems and their application in public health]. Cad Saude Publica. 2006;22:19-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 107] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Sistema de Informação Hospitalar (SIH). Manual Técnico operacional do Sistema. [cited 28 September 2022]. Available from: http://sihd.datasus.gov.br/documentos/documentos_sihd2.php. |

| 22. | Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Manual Técnico Operacional SIA/SUS. [cited 28 September 2022]. Available from: http://www1.saude.rs.gov.br/dados/1273242960988Manual_Operacional_SIA2010.pdf. |

| 23. | Fumery M, Singh S, Dulai PS, Gower-Rousseau C, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn WJ. Natural History of Adult Ulcerative Colitis in Population-based Cohorts: A Systematic Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16:343-356.e3. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 210] [Cited by in RCA: 319] [Article Influence: 45.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Maia Diniz I, Guerra AA Junior, Lovato Pires de Lemos L, Souza KM, Godman B, Bennie M, Wettermark B, de Assis Acurcio F, Alvares J, Gurgel Andrade EI, Leal Cherchiglia M, de Araújo VE. The long-term costs for treating multiple sclerosis in a 16-year retrospective cohort study in Brazil. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0199446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Kin C, Kate Bundorf M. As Infliximab Use for Ulcerative Colitis Has Increased, so Has the Rate of Surgical Resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017;21:1159-1165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Lima Martins A, Volpato RA, Zago-Gomes MDP. The prevalence and phenotype in Brazilian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2018;18:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Gasparini RG, Sassaki LY, Saad-Hossne R. Inflammatory bowel disease epidemiology in São Paulo State, Brazil. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2018;11:423-429. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Parente JM, Coy CS, Campelo V, Parente MP, Costa LA, da Silva RM, Stephan C, Zeitune JM. Inflammatory bowel disease in an underdeveloped region of Northeastern Brazil. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1197-206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 29. | Albuquerque MV, Viana ALD, Lima LD, Ferreira MP, Fusaro ER, Iozzi FL. Regional health inequalities: changes observed in Brazil from 2000-2016. Cien Saude Colet. 2017;22:1055-1064. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 17.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Solitano V, D'Amico F, Zacharopoulou E, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Danese S. Early Intervention in Ulcerative Colitis: Ready for Prime Time? J Clin Med. 2020;9:2646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Garud S, Peppercorn MA. Ulcerative colitis: current treatment strategies and future prospects. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:99-108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Gupta RB, Harpaz N, Itzkowitz S, Hossain S, Matula S, Kornbluth A, Bodian C, Ullman T. Histologic inflammation is a risk factor for progression to colorectal neoplasia in ulcerative colitis: a cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1099-105; quiz 1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 617] [Cited by in RCA: 566] [Article Influence: 31.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | [In memoriam Lieutenant Colonel Medical Corps Makso Sprung, M.D]. Vojnosanit Pregl. 1974;31:420. [PubMed] |

| 34. | Gordillo J, Zabana Y, Garcia-Planella E, Mañosa M, Llaó J, Gich I, Marín L, Szafranska J, Sáinz S, Bessa X, Cabré E, Domènech E. Prevalence and risk factors for colorectal adenomas in patients with ulcerative colitis. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:322-330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang Y, Ouyang Q; APDW 2004 Chinese IBD working group. Ulcerative colitis in China: retrospective analysis of 3100 hospitalized patients. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1450-1455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Park SC, Jeen YT. Current and emerging biologics for ulcerative colitis. Gut Liver. 2015;9:18-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, Sands BE, Hanauer S, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Van Assche G, Axler J, Kim HJ, Danese S, Fox I, Milch C, Sankoh S, Wyant T, Xu J, Parikh A; GEMINI 1 Study Group. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:699-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1576] [Cited by in RCA: 1844] [Article Influence: 153.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Stidham RW, Lee TC, Higgins PD, Deshpande AR, Sussman DA, Singal AG, Elmunzer BJ, Saini SD, Vijan S, Waljee AK. Systematic review with network meta-analysis: the efficacy of anti-tumour necrosis factor-alpha agents for the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:660-671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Ciência T e IE. Vedolizumabe para tratamento de pacientes com retocolite ulcerativa moderada a grave TT - Vedolizumab for treatment of patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis. 2019 [cited 28 September 2022]. Available from: http://conitec.gov.br/images/Consultas/Relatorios/2019/Relatorio_vedolizumabe_colite_ulcerativa_CP_45_2019.pdf. |

| 40. | Conitec. Retocolite Ulcerativa Protocolo Clínico e Diretrizes Terapêuticas de Retocolite Ulcerativa. 2021. [cited 28 September 2022]. Available from: https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/protocolo_clinico_terapeuticas_retocolite_ulcerativa.pdf. |

| 41. | Conitec. Adalimumabe, golimumabe, infliximabe e vedolizumabe para tratamento da retocolite ulcerativa moderada a grave. 2019. [cited 28 September 2022]. Available from: http://antigo-conitec.saude.gov.br/images/Consultas/Relatorios/2019/Relatrio_biologicos_colite_ulcerativa_CP_44_2019.pdf. |