Published online Dec 21, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i47.6165

Peer-review started: October 17, 2023

First decision: October 31, 2023

Revised: November 10, 2023

Accepted: December 2, 2023

Article in press: December 2, 2023

Published online: December 21, 2023

Processing time: 62 Days and 15.8 Hours

There is rapidly increasing uptake of GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) agonists such as semaglutide worldwide for weight loss and management of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). remains a paucity of safety data in the vulnerable NASH cirrhotic population. We report herein the first documented case of liver decom

Core Tip: Patients with NASH cirrhosis who lose weight rapidly with semaglutide are at risk of liver decompensation. This complication requires the immediate cessation of semaglutide and aggressive nutritional rehabilitation with supplemental protein feeds and micronutrients. Restoration of lost weight can lead to liver recompensation; however, consideration of liver transplantation should be given to patients who fail to respond to treatment.

- Citation: Peverelle M, Ng J, Peverelle J, Hirsch RD, Testro A. Liver decompensation after rapid weight loss from semaglutide in a patient with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis -associated cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(47): 6165-6167

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i47/6165.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i47.6165

We read with interest the systematic review and meta-analysis by Zhu et al[1] reporting on the efficacy and safety of semaglutide in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Analyzing three randomized control trials involving 458 patients, they found that semaglutide was effective at improving histologic and radiologic markers of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) activity but not histologic fibrosis. The risk of serious adverse events was similar compared to placebo, and importantly, no cases of hepatic decompensation occurred.

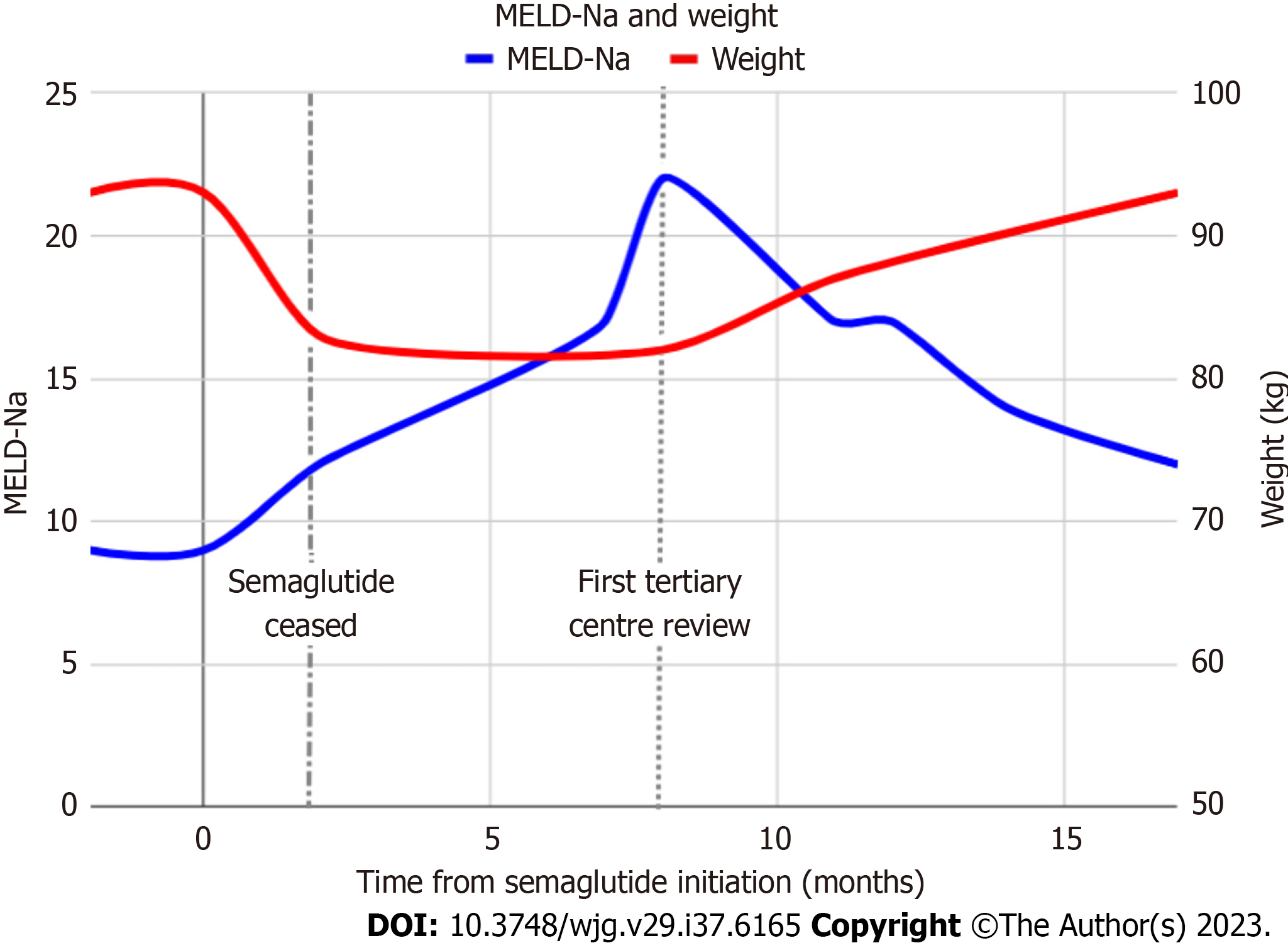

We herein present a case of liver decompensation in a patient with NASH cirrhosis after the use of semaglutide. A 68-year-old female with compensated NASH cirrhosis [Model for Endstage Liver Disease-Na (MELD-Na) score 11] was prescribed semaglutide 2.4 mg once weekly to manage her diabetes and obesity. Her other medications at the time included salbutamol for asthma. The semaglutide led to 10 kg weight loss (11% body weight) within 8 wk of treatment before it was stopped. After approximately 8% body weight loss she developed new onset hepatic encephalopathy (HE) requiring the use of lactulose and rifaximin. She also developed ascites requiring diuretic therapy (spironolactone 100 mg and frusemide 40 mg; further increases limited by postural hypotension) and two large-volume paracenteses. Patient adherence to prescribed medications was confirmed by her family during this time. Due to her rapid weight loss, her semaglutide was stopped. Despite stabilization of her weight, she continued to decompensate and her MELD-Na con

Our case highlights the potential risk of rapid weight loss with semaglutide in the vulnerable NASH cirrhosis population. In our case, the rapidity of weight loss was significantly greater compared to the studies included in Zhu

Clinicians should consider the use of semaglutide cautiously in patients with underlying NASH cirrhosis and should strictly adhere to the prescribing information and dose escalation protocols as recommended and consider using a lower dose of the drug. Failure to follow strict dose escalation protocol may lead to significant gastrointestinal side effects in

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Australia

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Barone M, Italy; Morozov S, Russia S-Editor: Lin C L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xu ZH

| 1. | Zhu K, Kakkar R, Chahal D, Yoshida EM, Hussaini T. Efficacy and safety of semaglutide in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:5327-5338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Loomba R, Abdelmalek MF, Armstrong MJ, Jara M, Kjær MS, Krarup N, Lawitz E, Ratziu V, Sanyal AJ, Schattenberg JM, Newsome PN; NN9931-4492 investigators. Semaglutide 2·4 mg once weekly in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis-related cirrhosis: a randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;8:511-522. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 141] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 119.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Eilenberg M, Langer FB, Beer A, Trauner M, Prager G, Staufer K. Significant Liver-Related Morbidity After Bariatric Surgery and Its Reversal-a Case Series. Obes Surg. 2018;28:812-819. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Verna EC, Berk PD. Role of fatty acids in the pathogenesis of obesity and fatty liver: impact of bariatric surgery. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:407-426. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van Zutphen T, Ciapaite J, Bloks VW, Ackereley C, Gerding A, Jurdzinski A, de Moraes RA, Zhang L, Wolters JC, Bischoff R, Wanders RJ, Houten SM, Bronte-Tinkew D, Shatseva T, Lewis GF, Groen AK, Reijngoud DJ, Bakker BM, Jonker JW, Kim PK, Bandsma RH. Malnutrition-associated liver steatosis and ATP depletion is caused by peroxisomal and mitochondrial dysfunction. J Hepatol. 2016;65:1198-1208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Drenick EJ, Fisler J, Johnson D. Hepatic steatosis after intestinal bypass--prevention and reversal by metronidazole, irrespective of protein-calorie malnutrition. Gastroenterology. 1982;82:535-548. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Moolenaar LR, de Waard NE, Heger M, de Haan LR, Slootmaekers CPJ, Nijboer WN, Tushuizen ME, van Golen RF. Liver Injury and Acute Liver Failure After Bariatric Surgery: An Overview of Potential Injury Mechanisms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2022;56:311-323. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |