Published online Sep 7, 2023. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v29.i33.5014

Peer-review started: May 13, 2023

First decision: May 30, 2023

Revised: July 3, 2023

Accepted: July 17, 2023

Article in press: July 17, 2023

Published online: September 7, 2023

Processing time: 110 Days and 22.6 Hours

Pulmonary carcinoids are rare, low-grade malignant tumors characterized by neuroendocrine differentiation and relatively indolent clinical behavior. Most cases present as a slow-growing polypoidal mass in the major bronchi leading to hemoptysis and pulmonary infection due to blockage of the distal bronchi. Carcinoid syndrome is a paraneoplastic syndrome caused by the systemic release of vasoactive substances that presents in 5% of patients with neuroendocrine tumors. Due to such nonspecific presentation, most patients are misdiagnosed or diagnosed late and may receive several courses of antibiotics to treat recurrent pneumonia before the tumor is diagnosed.

We report the case of a 48-year-old male who presented with cough, dyspnea, a history of recurrent pneumonitis, and therapy-refractory ulcerative colitis that completely subsided after the resection of a pulmonary carcinoid.

We report and emphasize pulmonary carcinoid as a differential diagnosis in patients with nonresponding inflammatory bowel diseases and recurrent pneumonia.

Core Tip: Pulmonary carcinoids are rare neuroendocrine tumors that may cause a paraneoplastic syndrome. We report the case of a 48-year-old man with a history of recurrent pneumonitis and therapy-refractory ulcerative colitis that was completely resolved after resection of a pulmonary carcinoid. Pulmonary carcinoid should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with unresponsive inflammatory bowel disease and recurrent pneumonia.

- Citation: Reyes CM, Klein H, Stögbauer F, Einwächter H, Boxberg M, Schirren M, Safi S, Hoffmann H. Carcinoid syndrome caused by a pulmonary carcinoid mimics intestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2023; 29(33): 5014-5019

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v29/i33/5014.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v29.i33.5014

Pulmonary carcinoids are rare, slow-growing neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) that account for 1%-2% of all primary lung cancers[1]. NETs arise from enterochromaffin or Kulchitsky cells lining the gastrointestinal tract (58%) and respiratory system (25%)[2]. Bronchial carcinoids commonly present with recurrent pneumonitis, cough, fever, and hemoptysis due to their central origin and hypervascularity[1]. Rarely, patients may present with features of carcinoid syndrome, a term applied to a collection of symptoms that are associated with the secretion of vasoactive substances by carcinoid tumors[3,4]. The main symptoms of carcinoid syndrome are cutaneous flushing, diarrhea, bronchospasms and, ultimately, carcinoid heart disease[3]. Carcinoid syndrome is predominantly associated with NETs that arise from the midgut in the setting of extensive liver metastases but may be present in patients with bronchial carcinoids[3]. Early detection is crucial because surgical excision of the tumor is the only curative approach and the main determinant of the prognosis[2].

A 48-year-old white man with a medical history of recurrent pneumonitis and therapy-resistant ulcerative colitis over 10 years presented with fever and cough with sputum production for 10 d. He reported resting dyspnea and pain over the right thoracic wall.

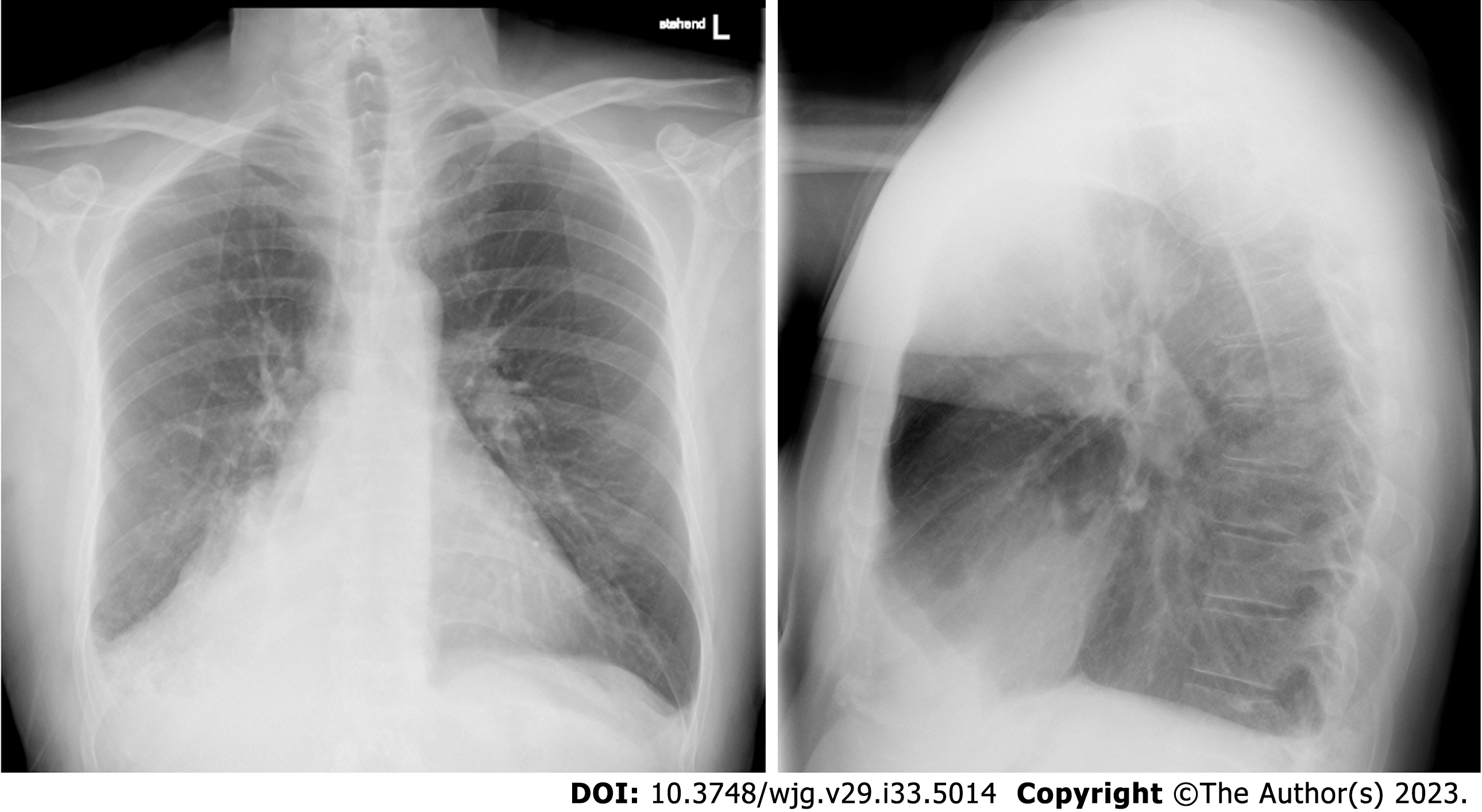

Under antibiotic therapy with moxifloxacin, no clinical improvement was reported. A chest roentgenogram showed an effaced right costo-phrenic angle and nonvisualization of the right hilar shadow suggestive of right lower lobe collapse (Figure 1).

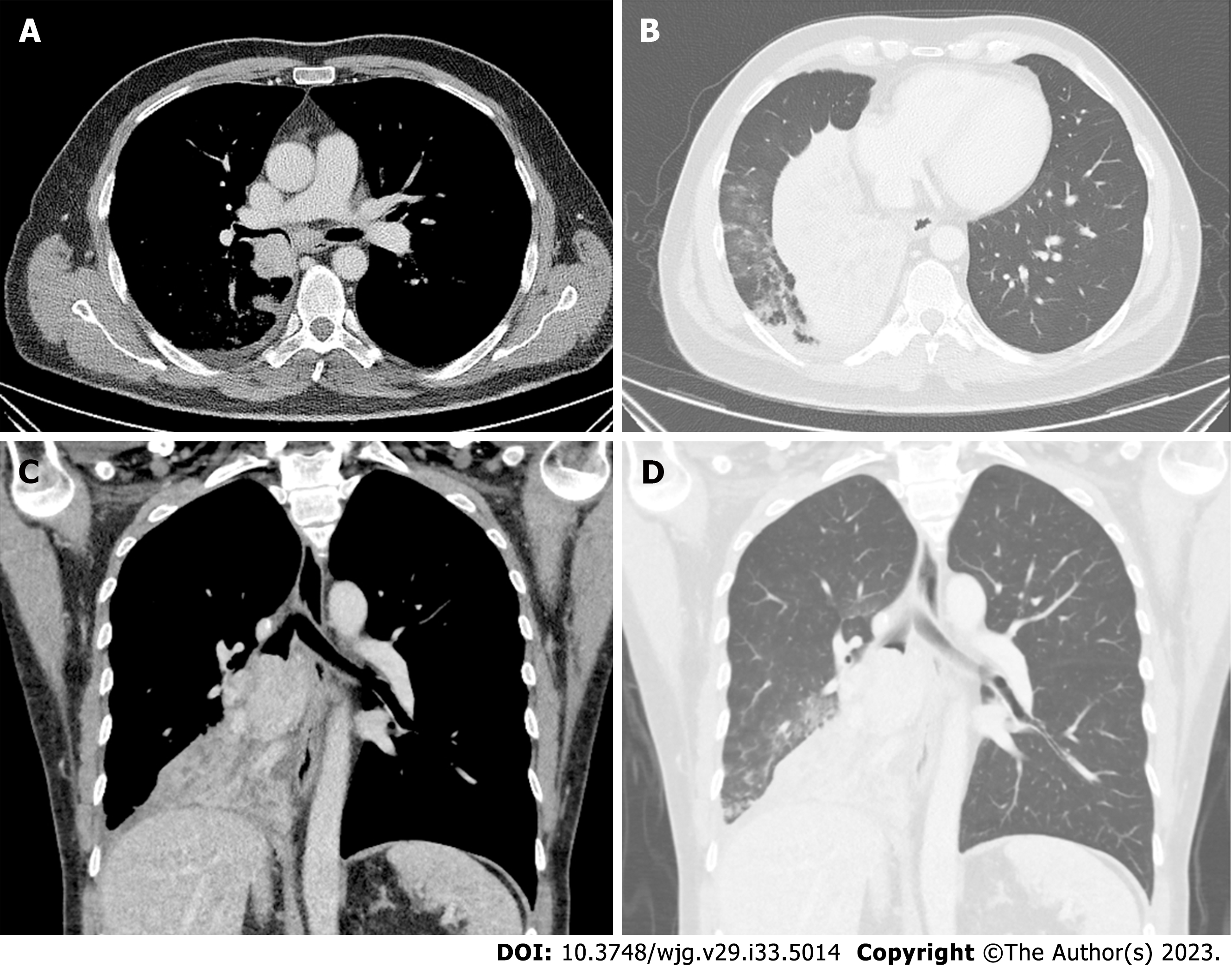

Bronchoscopy revealed complete occlusion of the right bronchus intermedius due to a smooth-walled vascular mass with intact overlying epithelium. A computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a well-defined round-to-oval, smoothly marginated tumor measuring 43 mm × 56 mm in size located endobronchially in the proximal right main stem bronchus causing complete collapse of the right middle and lower lobe (Figure 2). A PET-CT scan showed a low metabolically active mass in the lower lobe, consistent with a carcinoid tumor, and metabolically active prominent and probably reactive mediastinal and hilar lymph nodes.

The definitive diagnosis of typical bronchial carcinoid was confirmed in the transbronchial biopsy of the mass.

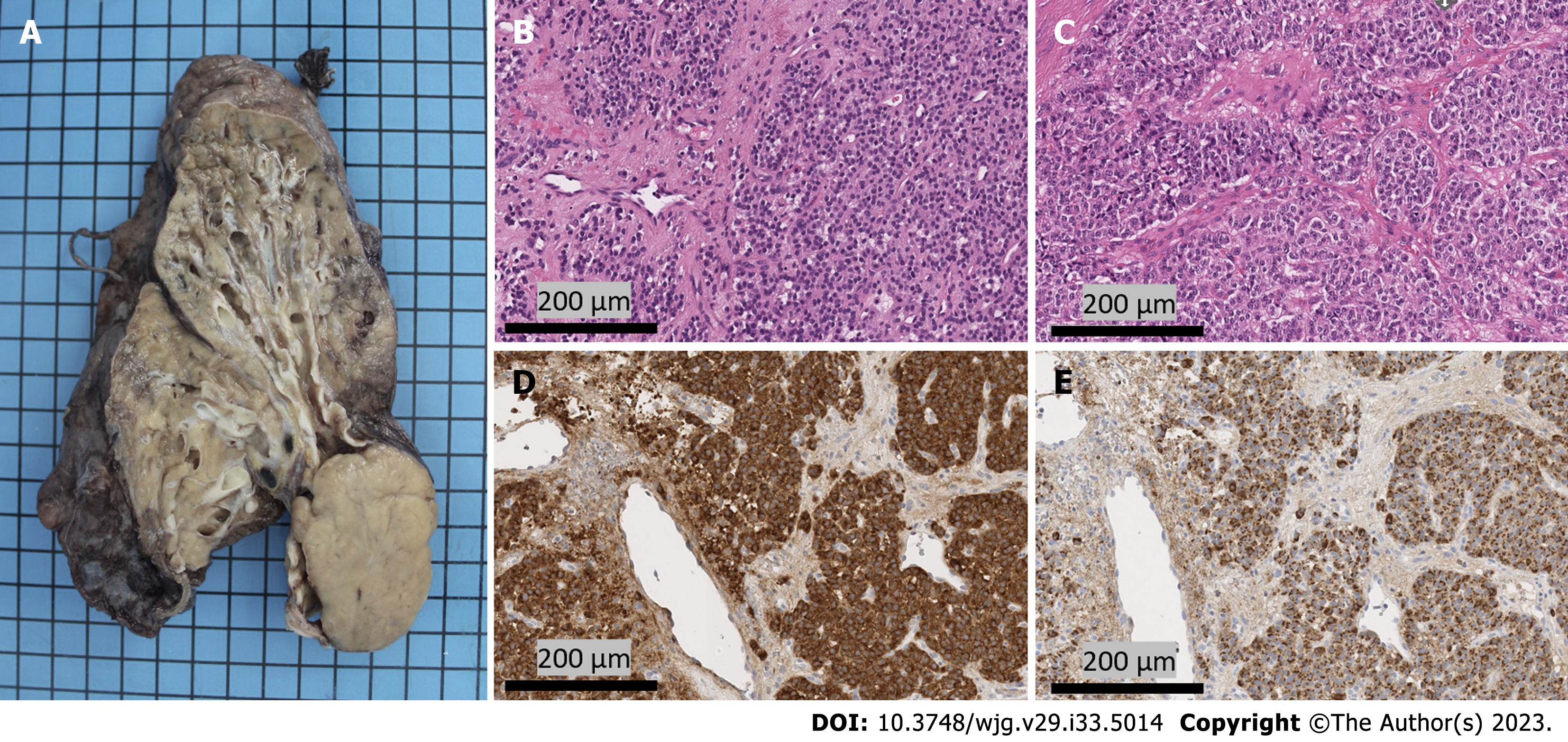

All pulmonary carcinoid tumors should be treated as malignancies, as the only curative approach is a margin-free surgical resection. A right middle and lower sleeve lobectomy with bronchoplastic repair and radical lymphadenectomy were performed. Histopathologic examination of the resected tumor (Figure 3) revealed a solid growth pattern of uniform tumor cells with granular chromatin. The histologic appearance of the resection specimen was consistent with the transbronchial biopsy specimen. Here, the mitotic rate was under 1%, with fewer than 2 mitoses in 2 mm², and necrosis was not detected. Strong immunohistochemical positivity for synaptophysin and chromogranin was detected, and somatostatin receptor subtype 2a showed strong membranous expression (score 3+). All of these features lead to the diagnosis of a typical carcinoid of the lung[5].

The patient had no postoperative complications. He was discharged home 14 d after the operation and was followed up at 3 mo, 6 mo, 10 mo, and 36 mo. On a DOTATATE PET scan performed 3 mo after the operation, there was no evidence of any lymphadenopathy or distant metastasis. At 36 mo after the operation, the patient was stable, with no evidence of recurrence in the DOTATATE PET scan. Unexpectedly, after tumor resection and in the absence of any therapy, the patient presented complete clinical remission of ulcerative colitis.

Long-standing therapy-resistant ulcerative colitis was first diagnosed in 2009. Initially, combined therapy with rectal and oral mesalazine was prescribed; however, the patient reported further persistent bloody diarrhea with acute disease flares approximately twice a year. On colonoscopy, pronounced erythema in the rectum with fibrin deposits and granularity of the mucosal surface was observed. All findings were consistent with the diagnosis of ulcerative colitis. The diagnosis of ulcerative proctitis was ultimately confirmed in the step biopsies. The addition of topical steroids did not relieve the symptoms of colitis. Furthermore, the patient reported an increased frequency of bowel movements accompanied by rectal tenesmus. After three months of remission induction therapy with high-dose systemic steroids, mild disease control was achieved; however, any attempt at dose reduction was not tolerated by the patient. For this reason, immunomodulatory therapy with azathioprine was initiated, which led to a notable alleviation of the symptoms and disease remission. Due to alterations in both ALT and AST levels, azathioprine therapy was replaced by 6-mercaptopurin in combination with systemic steroids. The intestinal manifestations responded moderately to this therapy, and the steroids were reduced over time. The therapy with 6-mercaptopurin was carried out until two weeks before the lung operation with a milder course of ulcerative colitis.

Remarkably, after resection of the pulmonary carcinoid, the patient presented an unaltered bowel habit with no need for therapy. In light of the clinical evolution of the intestinal symptoms, it is questionable whether the clinical manifestations of ulcerative colitis were exacerbated by the pulmonary carcinoid or whether they were part of a carcinoid syndrome.

Here, we report a case of a young adult with an over 10-year history of ulcerative colitis and concurrent pneumonitis episodes who was diagnosed with pulmonary carcinoid. After complete resection of the pulmonary carcinoid, the intestinal symptoms completely subsided with no need for further therapy even after three years of follow up. The presence of a 56 mm measuring pulmonary carcinoid suggests[6] that the carcinoid was already present at the time of the patient’s ulcerative colitis diagnosis. Pulmonary carcinoids are rare neoplasms that are able to synthesize and secrete neuroendocrine peptides into the central circulation, causing many symptoms, such as flushing or diarrhea. Taken together, these facts and the timely evolution of the condition indicated that the intestinal manifestations in this patient seemed to be exacerbated by the pulmonary carcinoid or even the result of a carcinoid syndrome. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of pulmonary carcinoid with this clinical presentation. Interestingly, studies in mice have shown that serotonin increases the susceptibility to experimental colitis[7].

The diagnosis of pulmonary carcinoids is often overlooked even in symptomatic patients due to low clinical suspicion and the various ways in which pulmonary carcinoids can present[8,9]. Apart from symptoms such as chest pain, atelectasis or pleural effusion, common pulmonary manifestations are hemoptysis, postobstructive pneumonitis, and dyspnea, especially in centrally located tumors, as in our case[1]. Carcinoids can also be associated with a variety of hormonally induced systemic symptoms due to gastrin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, serotonin, or histamine production, and this condition is termed carcinoid syndrome[9]. The most commonly encountered symptoms are flushing of the face, severe, debilitating diarrhea, and bronchospasms[10]. Metastatic tumor spread in the liver circumvents the hepatic inactivation of these substances and leads to the development of carcinoid syndrome. Rarely, bronchial and ovarian carcinoids can release hormones directly into the systemic circulation, thereby producing symptoms in the absence of liver metastasis[4]. Carcinoid syndrome-associated diarrhea is, as in our patient, unspecific and usually described as intermittent and sporadic. It is often accompanied by mild abdominal cramping and may become continuous when complicated by bacterial overgrowth[3]. This somewhat atypical course may explain the delayed diagnosis of NETs, which can sometimes occur after many years of unspecific symptoms that result in patients being diagnosed with an advanced incurable disease.

Typical bronchial carcinoids rarely metastasize and have an excellent prognosis even when regional lymph nodes are involved[2]. Surgery has been reported to provide a 5- and 10-year survival rate of > 90% for typical pulmonary carcinoids and is the treatment of choice[4].

In conclusion, the present case highlights that localized pulmonary carcinoids can potentially cause a carcinoid syndrome even in the absence of liver metastasis. Furthermore, intestinal manifestations, among other paraneoplastic symptoms, can precede symptoms of bronchial obstruction and superinfection. Thus, in patients with a history of recurring pneumonitis, the differential diagnosis of patients with persistent diarrhea and abdominal cramping despite optimum medical treatment should include pulmonary carcinoids[2]. A strong clinical suspicion aided by radiological examinations, including chest CT scans, enables the timely and accurate diagnosis of pulmonary carcinoids, which is crucial for early surgical resection[1].

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Germany

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Liu YC, China; Yan B, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Cai YX

| 1. | Bora MK, Vithiavathi S. Primary bronchial carcinoid: A rare differential diagnosis of pulmonary koch in young adult patient. Lung India. 2012;29:59-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mindaye ET, Tesfaye GK. Bronchial carcinoid tumor: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;77:349-352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Rubin de Celis Ferrari AC, Glasberg J, Riechelmann RP. Carcinoid syndrome: update on the pathophysiology and treatment. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e490s. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Belicová M, Prídavková D, Jankovičová V, Balážová K, Mokáň M. Bronchial carcinoid, unusual manifestation: A case report. J Xiangya Med. 2020;5:7. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | World Health Organization. WHO classification of tumours of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. 2015. [cited 1 July 2023]. Available from: https://www.iarc.who.int/news-events/who-classification-of-tumours-of-the-lung-pleura-thymus-and-heart-4th-edition/. |

| 6. | Russ DH, Barta JA, Evans NR, Stapp RT, Kane GC. Volume Doubling Time of Pulmonary Carcinoid Tumors Measured by Computed Tomography. Clin Lung Cancer. 2022;23:e453-e459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Haq S, Wang H, Grondin J, Banskota S, Marshall JK, Khan II, Chauhan U, Cote F, Kwon YH, Philpott D, Brumell JH, Surette M, Steinberg GR, Khan WI. Disruption of autophagy by increased 5-HT alters gut microbiota and enhances susceptibility to experimental colitis and Crohn’s disease. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabi6442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Orakwe O. Bronchial carcinoid tumor: Case report. J Lung Pulm Respir Res. 2014;1:1-3. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 9. | Moraes TJ, Langer JC, Forte V, Shayan K, Sweezey N. Pediatric pulmonary carcinoid: a case report and review of the literature. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35:318-322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Mota JM, Sousa LG, Riechelmann RP. Complications from carcinoid syndrome: review of the current evidence. Ecancermedicalscience. 2016;10:662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |